John Kenneth Muir's Blog

October 13, 2025

30 Years Ago: Jade (1995)

In the early 1990s, outspoken screenwriter Joe Eszterhas was the toast of Hollywood.

The writer behind the mega-hit Basic Instinct (1992) quickly became the highest-paid screenwriter in history, not to mention one of the most controversial. And for good reason. His scripts enthusiastically blended brutal violence with lurid sex, and his outlook on women was either blatantly misogynist or extremely feminist, depending on your interpretation.

Eszterhas contributed further "erotic" thrillers -- such as Sliver (1993) -- to Hollywood's revival and re-interpretation of the film noir aesthetic but with pumped-up, acrobatic sex scenes, macho dialogue, and strange murders aplenty. The result? Suddenly, cineplexes were jammed-packed with so-called "sexy" thrillers like Madonna's (atrocious) Body of Evidence (1993), the equally-moribund Whispers in the Dark (1992) and the uninspiring Final Analysis (1992).

However, by the half-way point of the Age of Clinton (1995), the trend had burned itself out, just like the hot candle wax poured on Willem Dafoe's privates by Madonna in Body of Evidence . Eszterhas's remarkable fortunes were notably reversed, and the writer shepherded two notorious bombs to theaters, the ridiculous and campy (though extremely enjoyable) Showgirls [1994]) and the dead-on-arrival William Friedkin film, Jade (1995).

The outline -- the outline, mind you -- of Jade was purchased by Paramount's Sherry Lansing (Friedkin's wife) for a whopping 2.5 million dollars.

The final film, however, was a Waterloo for all involved. Jade only grossed ten million dollars against a fifty million dollar budget, and was almost universally critically-reviled. Most of the animosity, however, was directed at Ezsterhas's turgid script rather than the late Friedkin's direction. It's also clear in retrospect that Jade - although no masterpiece (and not in the same class as Sorcerer, Cruising or To Live and Die in L.A .) -- suffered from a double backlash that had little to do with the specifics of the film itself.

First, critics were still gunning for the by-now millionaire celebrity writer, Ezsterhas, desiring to punish him for his egregious success (and his fall from grace, with Showgirls ). I'm not sure why this is the case, but many critics love to take down someone "big" who picks a bad project, or who, after previous successes, makes a less-successful film (see: Kevin Costner, Ben Affleck, M. Night Shyamalan or George Lucas.)

Secondly, Jade starred David Caruso, a talent Friedkin once described in an interview (with Charlie Rose) as "the new Steve McQueen." As you may recall, Caruso walked away from a starring role in the highly-successful Steve Bochco TV series NYPD Blue after one season, and critics and audiences interpreted his departure after so brief a spell as one of supreme arrogance and ingratitude. Caruso was also duly punished for his sins: both films he made in 1995, Kiss of Death and Jade , suffered ignoble deaths at the box office. People were angry with Caruso, and his film career evaporated because of it.

Again, none of this historical background is meant to imply or suggest that Jade isn't responsible for its own trespasses; only that -- starting out -- this critically-derided William Friedkin film had two big strikes against it. Still, Jade might have weathered the twin Eszterhas/Caruso backlash had it been a stronger, better-written film. As it stands, it suffers from a confusing, underwhelming climax, and all the touches we now typically associate with your typical Eszterhas script.

In other words, Jade feels ugly, leering, and crass. The particular details of the film's narrative are so luridly shocking (a millionaire collects pubic hair trophies of his sexual conquests! The prostitute known as Jade is famous for taking it...uh...the Greek Way!) that we're momentarily distracted from the fact that the characters have little depth and that the story is muddled beyond belief.

All of these problems are present and accounted for in Basic Instinct too , by the way, but Verhoeven directed that film with a zealous, even bombastic sense of voyeurism, one bordering on circus-like, and in the lead role Sharon Stone proved herself a game, self-aware ringmaster, a hyper-femme fatale for the ages. Jerry Goldsmith's score evoked Hitchcock, and with her patented Ice Princess act, Stone's character could be traced directly back to Kim Novak in Vertigo (1958). Even if the film wasn't authentically Hitchcockian in technique and meticulous plotting, it felt enough like Hitchcock to pass muster in March of 1992.

But William Friedkin isn't Paul Verhoeven in either style or temperament.

Verhoeven has proven to be at his best as a wicked social satirist, in efforts such as RoboCop (1987) and Starship Troopers (1997). By contrast, Friekdin was a more gloomy, realistic, existentialist director; one who tends to ruminate on heavier matters. To Live and Die in L.A . and The French Connection both draw a profound moral equivalency between obsessive cops and their criminal quarry. Sorcerer obsesses on the fickle whimsy of fate, and The Exorcist deals with the idea that true evil dwells in this world. In Jade , it's clear that Friedkin is examining something else that fascinates him, in this case, sexual jealousy, and the manner in which people either exorcise it, or hide it from society.

The film noir format has always concerned "the underneath," the simmering, ignoble motives that drive a man to desperation; to commit a crime; to fall in love with the wrong woman; or to kill an enemy. Friedkin, in crafting Jade , utilizes the leitmotif of "the mask" to explore that duality of the surface world and the underneath; to plumb the depths of public/private faces.

One of the first shots in the film, for instance, involves a slow, menacing (and beautifully orchestrated) glide up a long, elegant stairway The camera's prey is -- no surprise here -- a dark black mask on display at the top of that staircase. We seem to steadily approach the empty eye slits of the ebony mask, as if the camera wants us to put it on ourselves. Later, evidence found at a crime scene includes a bloodied mask of another kind, a fertility mask. Critic Bob Stephens, writing for The San Francisco Examiner made clever note of the preponderance of masks in Jade :

"Ceremonial and psychological masks dominate William Friedkin's most recent film, "Jade," which is set in San Francisco. In Friedkin's intriguing murder mystery, we encounter the menacing fertility masks of primitive cultures, colorful masks in the celebratory Chinese New Year parade, opaque public personas and the "masks" of identities assumed in hedonistic sexual activities. In "Jade" people are not what they appear to be; with each new revelation of a homicide investigation, the relationships of politicians, legal agencies and three friends change drastically."

Indeed. Jade's story is one in which masks play a crucial role, and which the truth underneath those masks shocks, surprises and confounds. The film's narrative centers around San Francisco's assistant district attorney, David Corelli (David Caruso) as he investigates the stunning and brutal murder of a local philanthropist. The eccentric man died in a compromising position and the one of the few clues as to the identity of the perpetrator involves his collection of pubic hair snippets from sexual conquests. Yes, you read that right.

One such pubic hair snippet apparently belongs to a mysterious high-class prostitute called Jade. Jade's real identity is unknown, but as the case deepens, Corelli draws closer to finding her, and the murderer too. The case leads Corelli to an investigation of California's governor (Richard Crenna), one of Jade's clients. More disturbingly, it leads Corelli straight to his best friends from college -- Matt (Chazz Palminteri) and Trina (Linda Fiorentino) Gavin -- a high-powered married couple living in San Francisco. Matt is a ruthless attorney, and Trina is a clinical psychologist. That very day, Trina happened to visit the murder victim. She offers a plausible explanation for the social call, but her fingerprints are soon found on the murder weapon: a ceremonial hatchet.

David also finds a cuff link at the scene of the crime, and it too is a crucial clue. Meanwhile, the police (led by Michael Biehn) zero in on Trina. Adding to the cloud of guilt surrounding her, she writes successfully (and gives lectures...) about an issue in "the changing workplace." In particular, Trina discusses how it is important to "distinguish between someone who's had a bad day that ends in a temper tantrum and someone whose failure to resist aggressive impulses results in serious destructive acts."

What happens when people are "no longer able to control their urges?"

According to Trina, "they disassociate from their own actions, often experiencing an hysterical blindness." "They're blind," she establishes, "...to the darkness within themselves."

In most movies of this type, Trina's psycho-babble dialogue would prove a sort of explanation of the killer's motive or mind-set. What separates Jade from the sleazy erotic-thriller pack, and what marks it as a Friedkin film, is that Trina's description covers literally every character in the film.

To wit: Trina leads a double life as Jade -- the hooker every man wants to be with. Her husband Matt...well, if you've seen the movie, you know just how "dark" he is. He's an amoral lawyer and a monstrous, cruel husband, and worse, doesn't even practice foreplay. David himself is pretty dark, threatening the district attorney in order to stay on the Jade case (and gain a political foothold, perhaps, in S.F.).

Michael Biehn's character has secrets too...his public face hides a dark, private one.. As for the governor, he has orchestrated a massive conspiracy to cover his sexual dalliance, all the while maintaining a smile and a laconic demeanor. The "masks" people wear in public, we see, are the masks that allow them to - in Trina's vernacular -"disassociate" themselves from their urges, their moral failings, their monstrous deeds.

As in the best examples of the film noir genre, in Jade it's not merely a few bad apples who are corrupt...it is the world itself that is twisted and perverse. And that tenet certainly fits in with the gritty nihilism we've detected in Friedkin's other cinematic works. There's a great shot in the film, early on, that seems to express visually this conceit. At a ritzy San Francisco party, an empty tuxedo jacket hovers near the ceiling, over the revellers, social climbers and wannabes - the "haves and the have mores." As the shot suggests, they're all sort of empty suits, devoid of morality and social purpose beyond hedonism and self-aggrandizement. On the soundtrack, "Isn't it Romantic?" plays ironically.

So, is Jade misogynist or feminist? Well, the film concerns a woman subjugated and enslaved by her callous, two-timing husband, who - while donning her mask of disassociation -- steps out on her marriage to experience sexual pleasures with other men. This act may make Jade/Trina immoral, but it certainly doesn't make her a monster.

Again, this is made clear through Friedkin's savvy staging of a scene involving Matt and Trina making love. Matt mounts Trina without any foreplay whatsoever, and selfishly - and painfully - has very brief sex with her (I was going to write "makes love to her" but that was clearly the wrong phrase). For the duration of this act, Friedkin's camera remains on Trina's face; in relatively tight shot. A tear falls down her cheek. We detect on Trina's face a flurry of conflicting emotions. There's physical pain; there's emotional hurt; and then the mask returns. The staging -- close on Trina -- makes us feel the pain too and helps us understand that although she may make questionable moral decisions, she's hardly the film's villain. I don't believe the film is misogynist because "Jade" (unlike Catherine Trammell) is not a loopy psycho-killer. Her worst transgression is the search for sexual satisfaction outside of marriage. True, she takes that quest a bit far...but it is mostly the men in Jade who are the monsters.

I would also argue that the film isn't exactly feminist. Jade -- like all the other characters in the film -- dons the public "mask" of propriety while shedding it in private. Just because she's a woman, she's not automatically better than the men. The movie doesn't exactly approve of her of what she's done. In fact, Jade doesn't exactly approve of herself or what she's done. There's one mask in the film even she is ashamed to wear: that of a stocking pulled tight over her face, while a sexual partner screws her from behind. This moment occurs during a sleazy hotel room tryst, and the stocking makes Jade's face look deformed, distorted...even piggish. This is where Jade draws the line; where her ability to "disassociate" fails, and even she feels exploited.

Jade is a thoroughly fascinating film, but ultimately a somewhat unsatisfying and opaque one. Friedkin wants to examine the characters and ideas here with some depth, but the script rarely affords him the opportunity to go beyond the superficial, except in his choice of images. And the final revelatory scene raises more questions than it answers. For instance, if the killer of the philanthropist is whom the script tells us he is, then why the ritualistic nature of that murder? Why would the culprit -- as fingered by the screenplay -- arrange the body in such a fashion? It makes no sense in terms of motivation, in terms of narrative, and in terms of character. It's in that moment you realize how poorly-constructed the film's screenplay is; despite the interesting themes that occasionally make it tantalizing or alluring.

"The frustrating thing about Jade ," wrote critic Carlo Cavagna, "is that it proves Friedkin still has it."

Cavagna goes on to explain: "The drawn-out opening sequence, a build-up to a murder during which the camera drifts through an opulent mansion filled with valuable artwork, including several eerie masks, is masterful. The signature of the artist who made The Exorcist is unmistakable. Moreover, the protracted car chase an hour into the film is nearly the equal of Friedkin's exceptional car chases in The French Connection and To Live and Die in L.A. , and recalls similarly stomach-lurching work by John Frankenheimer in The French Connection II and Ronin . The secret seems to lie in not overdoing the action and instead allowing the intensity of the actors to play into the scene, while at the same time putting a camera in the car to show the fracas from the driver's perspective."

There are some good points made there and I agree with them to a large extent. Jade occasionally struts with a sense of anticipatory dread and foreboding that is hard to dismiss. And Linda Fiorentino -- star of a fantastic film noir called The Last Seduction (1994) -- is beguiling. Nonetheless, I prefer Friedkin in a more "gritty" and realistic mode ( The French Connection or Sorcerer ). The expressionistic editing with jolts and subliminal flashes -- a new style when Jade vetted it in 1995 -- has, alas, become boring de rigueur just adds to the triteness of the story.

I also enjoy the Chinatown chase scene -- or what Friedkin calls an "anti-chase" scene since it involves cars stopped by traffic for long intervals -- but as skillful as it is from a purely technical perspective, this sequence doesn't cover any new ground for this artist. Before Jade , we already knew that Friedkin could stage, direct and edit a brilliant car chase. The impression here is that the director is searching -- desperately searching -- for some way to make the risible screenplay more engaging and punchy.

That Friedkin succeeds in that difficult quest with both his "masks" motif and his adrenaline-inducing car chase is a testament to his talent. At the very least, this film is intriguing. Jade may still be a mediocre film, but it's worth at least one viewing if you enjoy film noir, not to mention the spectacle of a great director working around a script to make his points with crafty visuals.

October 11, 2025

Abnormal Fixation Returns for Season Two on February 11, 2026

October 10, 2025

AF is a semi-finalist at Iceberg Film Awards!

I am very proud to report that our indie, low-budget mockumentary web series Abnormal Fixation (entering its second season in 2026) was just announced as a semi-finalist in the category of new media/episodic series at the Iceberg Film Awards in Oslo!

Congratulations to the cast and crew for this continued recognition, as we wrap up our film festival circuit.

Also, special thanks to Iceberg Film Awards for the honor!

September 30, 2025

50 Years Ago: The Ultimate Warrior (1975)

“It’s interesting what becomes valuable to us when almost everything is taken away,” one character muses in The Ultimate Warrior (1975), a violent action film that heavily forecasts The Road Warrior (1982), Cyborg (1989) and other films of the post-apocalyptic sub-genre.

In this case, it is Yul Brynner rather than Mel Gibson or Jean Claude Van Damme who plays a warrior of the wasteland, one who must protect the remnants -- and indeed the future -- of human civilization.

As in the case of the other films name-checked above, there’s a powerful Western vibe or overlay to The Ultimate Warrior. This is the story of a Clint Eastwood-like stranger who arrives at the City, and either saves it from injustice, or induces it to experience a rebirth.

It’s fascinating how the hero/stranger in such tales is always an outsider to the community or village at large, isn’t it?

The myth of the hero on a white horse arriving to clean up town -- and then leave it for the better -- is a deeply entrenched one in American culture. So much so that it still exists today in political campaigns. Everyone (on both sides of the aisle) wants to be cast as the heroic outsider riding into corrupt/failed Washington D.C. to clean it up.

The Ultimate Warrior -- directed by Robert Clouse -- certainly puts an interesting spin on this old archetype, recognizing in this case that the City will fall, but that mankind can survive nonetheless. The hero’s responsibility is not, then, to the City, in this case, but to the very future of the species. The film uses as symbols for that future both plant seeds, and a human fetus, carried in the abdomen of quite possibly the world’s last mother.

The future world of 2012 (!) as depicted viscerally in The Ultimate Warrior is one of starvation and desperation, scarcity and shortages. There is no gasoline, no medicine, and no hope. The Baron’s (Max Von Sydow) community suffers from a plague of “fatalism,” according to the film’s dialogue.

In terms of historical context, it is easy to see why the apocalypse takes this form. The film arises, like No Blade of Grass (1970) or Z.P.G. (Zero Population Growth ) (1972) from an age in which resource shortages, pollution and over-population looked like the trifecta of impending doomsdays, the three-headed bullet that had our name on it. Similarly, the country was still careening from the morale-sucking failures of the Vietnam War and fall-out from the Watergate Scandal. “Fatalism,” in those days, wasn’t the purview of only sci-fi films.

The film’s great virtue is its sense that mankind will endure. That fatalism can be outlived. The final scene -- set outside the confines of the de-humanized City -- promises a re-birth of hope, and an end to the fatalism that reduced man to selfish barbarian.

But of course, such catharsis can only arise after a particular brutal confrontation between Brynner and William Smith -- local warlord -- in a subway car.

That’s as it should be, however, since this is an action film. The Ultimate Warrior is vastly underrated in terms of its action, story, and value to the genre, but even worse, it often gets no credit for imagining the savagery of the post-apocalyptic world that filmmakers and critics would later associate with the Mad Max saga. It’s a film that deserves a second look, even forty years later.

In the year 2012, the civilized world has collapsed into anarchy due to famine. The Baron (Max Von Sydow) -- the leader of small community of survivors in New York City --realizes that his people will not survive long when faced with vile scavengers like the evil Carrot (William Smith) and his men.

Thus, the Baron recruits a soldier of fortune named Carson (Yul Brynner) to act as guardian to his people.

But the Baron has another motive for bringing the warrior into the fold. He recognizes the inevitable; that there is no future in city life. Specifically, The Baron wants to send his pregnant daughter, Melinda (Joanna Miles) to safety in North Carolina along with a batch of specially-engineered seeds that can grow despite the famine, and re-start the cycle of life.

The Baron tasks Carson with the care of his daughter and the seeds during the journey, but Carrot does everything in his power to stop the mission.

The Baron’s people are none-too-happy either, to learn that their leader has determined that their lives and futures are expendable.

The Ultimate Warrior’s depiction of its dark future world remains quite powerful. The city looks like a vast junkyard, and the Baron’s community lives on a city block barricaded on all sides. The entrance is accessible only through a parked-bus, and inside the community we see small gardens, wind mills (for energy production), and a community pantry running very low on provisions.

Impressively, The Ultimate Warrior considers that in a new world order like this one, new laws will be necessary, and the film reveals how even the best society’s -- like the one established by the Baron -- must operate on draconian law. There’s nothing to waste, nothing to squander, and yet the laws are so harsh that some essential sense of humanity is sacrificed.

For example, one citizen in the compound is accused of stealing a tomato, and forced to endure cruel justice. The Baron declares “Give him to the street people” and the offender is cast-out into the urban jungle. The Baron pays for his own trespasses as well. After sending away his daughter, Carson, and the seeds, he stays behind, and his own people beat him to death for selling them out. This sequence seems indicative of the proverb that those who live by the sword shall die by the sword. The Baron showed no mercy to offenders, and is, finally, shown no mercy, himself. A real sense of human savagery permeates The Ultimate Warrior , and one sequence involves the desperate mother and father of a small baby venturing out into the “wilderness” of New York to acquire powdered milk for their infant. A less frank, less honest film would have had them survive; would have had the hero rescue them. In this case, Carson is too late to help the family, and barely escapes with his own life. The fate of the baby is pretty grim too, an indication that the City is running out of tomorrows.

The Ultimate Warriors’ last act leaves behind the terror of the City, as Melinda and Carson (carrying the seeds), flee the metropolis through the subway system, Carrot and his men in pursuit. In this section of the film, the tension is especially high because The Baron -- Melinda’s father -- has actually given explicit instructions that Carson is to consider the fate of the seeds ahead of the fate of Melinda and her child.

That’s how desperate things have gotten for the human race. Family ties are now less important that a life-giving crop. When Melinda goes into labor, with Carrot’s men in pursuit, the film reaches its pinnacle of anxiety, since one wonders what decision Carson will ultimately make. It’s a tough choice, and one I don’t envy.

Carson chooses the morality of the old world, interestingly, and stays with the pregnant mother. He thus risks everything, but maintains his soul. It’s a fair trade, given the film’s outcome. As the titular “ultimate warrior,” Carson dispatches Carrot and his men with great aplomb, violence and blood-shed. The final set-piece in the subway (wherein Carson must chop off his own hand to kill Carrot) is gruesome in the extreme, but the final shots of Carson, Melinda and her baby reaching the picturesque beaches of North Carolina provide the film its final punctuation, a visual and emotional catharsis that makes the whole journey worthwhile.

For my money, the cutthroat No Blade of Grass still takes the cake as the bluntest, nastiest slice of post-apocalyptic life in the 1970s cinema, but The Ultimate Warrior absolutely points the way to the genre’s future. The film re-purposes old Western myths and tropes but doesn’t candy-coat the grim realities its characters encounter. While it is not, perhaps the “ultimate” post-apocalyptic film, The Ultimate Warrior is nonetheless a really fine piece of work, and the grandfather, perhaps, of The Road Warrior.

September 29, 2025

40 Years Ago: Amazing Stories (1985)

The 1985-1986 television season brought the world the Great Anthology War. It was the year that CBS revived The Twilight Zone , The Ray Bradbury Theater premiered in syndication, and NBC resurrected Alfred Hitchcock Presents .

Meanwhile, The Hitchhiker and Tales from the Darkside were already broadcasting their later seasons on HBO and in local syndication, too.

The most ballyhooed anthology of all, however, was Steven Spielberg's Amazing Stories , which aired on Sunday nights at 8:00 pm on NBC, and which was guaranteed for a full two seasons -- a whopping forty-four episodes -- before the first episode even premiered. Each half-hour installment was budgeted at the princely-sum of $800,000 dollars.

Amazing Stories, however, didn't quite live up to the hype.

In fact, I'll never forget my (bitter) disappointment with the series' first few installments. "Ghost Train" was a special effects-laden variation of an old One Step Beyond story called "Goodbye, Grandpa," only re-made to tug at the heart-strings, and "The Mission" -- a claustrophobic, well-shot World War II story set aboard a damaged bomber -- ended with a fantasy cartoon moment out of left field.

Critics didn't hold back.

The New York Times called the series a "spotty skein of cliches, sentimentality and ordinary hokum." Tom Shales termed the Spielberg program "one of the worst ten shows of all time, in any category...over-cute and over-produced...with primitive premises."

And at The New Leader Marvin Kitman coined the series "Appalling Stories."

Despite the bad reviews, however, the opening or introductory montage for Amazing Stories remains absolutely stirring.

Accompanied by a soaring, triumphant John Williams theme song, the introduction dramatizes -- in a short amount of time -- nothing less than the entire history of storytelling.

We begin in prehistory, as a caveman family (no, not Korg 70,000 BC...) sits around a blazing campfire, and a grandfatherly tribe leader dramatically tells a remarkable tale, his loved ones at rapt attention.

As the camera probes closer, we see, in close-up, the man's passion for his stories. At this point in our development, oral storytelling was the mode of communicating and maintaining a common or shared history.

In the next series of images, we move up through the ashes of the tribe's camp-fire, and ascend towards modernity.

First, we see an ancient Egyptian construction, a tomb perhaps, and witness a scroll unfurl, with a story inscribed upon it.

Next, we move up and forward into the Middle Ages, and a cathedral, where a bound book flies the length of the chamber.

The CGI here may look primitive today, but it still gets the job done. The imagery reminds us of the role that the written word, and storytelling, have played in human civilization across the centuries. In this span, words on a page are a way of maintaining history, and sharing favorite tales.

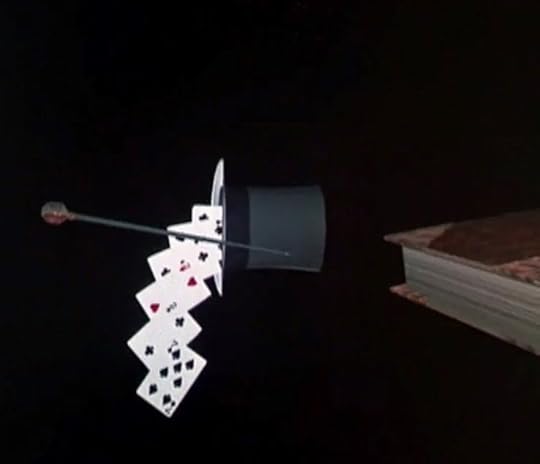

Next, the flying book promises stories of horror (represented by a painting of a haunted house) and magic (symbolized by a magician's black hat, and playing cards...).

We're not just countenancing run-of-the-mill stories then, the imagery suggests, but amazing, wondrous ones.

The spaceship veers off and we turn our attention back to planet Earth. We move toward the planet, and careen down towards a 20th century city in America...

Next our series title forms.

Say what you want about the quality of the actual stories depicted on this Steven Spielberg TV series, the introduction remains an inspiration, and a wonderful journey through the history of storytelling.

Perhaps the stories themselves felt so lacking, in part, because this introduction (and John Williams theme...) raised expectations to a near impossible level.Here's the intro to Amazing Stories in living color, 40 years later:

September 28, 2025

60 Years Ago: Ghidrah The Three Headed Monster (1965)

Godzilla makes the dramatic shift from being a villain and enemy of the human world to a dedicated (if reluctant…) Earth defender in the rip-roaring Toho effort, Ghidrah: The Three Headed Monster (1965).

This film also introduces the world to Godzilla’s key nemesis: the three-headed flying alien dragon known as King Ghidorah.

Ghidorah would return to battle Godzilla in many other films, including the brilliant adventure Monster Zero (1970), Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah (1991), and Godzilla: Final Wars (2004), to name just a few titles.

The enduring charm of Ghidrah: The Three Headed Monster, in large part, rests on its fanciful depiction of the monster world and, importantly, the monster viewpoint about that world.

Specifically, in the film’s delightful and unexpected final act, humanity asks for assistance battling the berserker Ghidrah, and Godzilla and Rodan must consider their priorities.

Are they man’s enemies, or do these beasts have a basis for cooperation with the human race?

Fortunately for mankind, Mothra is present to talk some sense into the recalcitrant Godzilla…

“These monsters are as stupid as human beings!” A foreign princess, Selina (Akiko Wakabayashi) is presumed dead after her plane is destroyed by assassins en route to Japan.

However, Selina soon re-appears in perfect health...but claiming to be a Martian princess.

In this new identity, Selina warns the people of Earth of an impending crisis, a repeat of the very one that destroyed her advanced home world.

While assassins from her home-land continue to seek to assassinate Selina, the alien princess’s warnings come to pass. As she forecasts, the fearsome pterodactyl Rodan awakens at Mount Aso, and Godzilla ascends from the sea.

Selina’s protector, Detective Shindo (Yosuke Natsuki) and psychiatrist Dr. Tsukamoto (Takashi Shimura) become convinced that Selina is acyually possessed by the spirit of an alien, and she makes a final, dire prediction. The monster that destroyed her home planet, Mars, in a matter of months, is now on Earth.

This too comes to pass, as King Ghidrah, or Ghidorah -- a three-headed goliath -- emerges from a meteor and lays waste to Japan.

Desperate, authorities make an effort to solicit Mothra’s help on Infant Island, and the giant insect acquiesces.

However, Mothra alone cannot defeat Ghidorah. So Mothra attempts to convince the quarrelsome Godzilla and Rodan to join forces and vanquish their common enemy, but it is not an easy sell.

When Mothra decides to go it alone, and is savagely attacked -- and ridiculed -- by malevolent Ghidorah, however, Godzilla comes to the rescue, followed by Rodan…

“Godzilla, what terrible language!”

The theme of cooperation, already given voice in Godzilla vs. The Thing (1964) is front and center in Ghidrah: The Three Headed Monster. Here, Godzilla and Rodan must stop their bickering -- with the help of a third monster, Mothra -- and defend the Earth from a threat of monumental proportions.

In terms of metaphor, it is not difficult to gaze at the film as a post-Cuban Missile Crisis, Cold War Era plea for sanity and cooperation among the argumentative powers of the world. If we follow it through symbolically, Godzilla may here represent the U.S. (as he is the avatar of American nuclear tests), Rodan the Soviet Union, and Mothra...level-headed, practical Japan. Only by all three “monsters” (or nations…) working together will the “alien” Ghidorah be defeated.

This theme finds voice in the brilliant finale, as Mothra, Godzilla, and Rodan share a meeting of the minds, or international monster summit of sorts. Mothra attempts to sway them with reason and logic, but Godzilla and Rodan are too busy kicking rocks into each other’s faces, at least at first, to listen. Eventually Mothra gets their attention, and then Godzilla and Rodan must consider their options.

They both hate mankind, and remember, importantly, that mankind hates them. Why should they help?

Well, as Mothra points out, we all share this Earth together, and so Godzilla and Rodan must put their hatred for man aside and do what is right for the planet.

I absolutely love the imagination and audacity of this film's climactic sequence. Mothra’s tiny princesses translate for the human audience while three monsters gurgle, growl and squeal at one another in serious conversation, determining the fate of the planet in the process.

This sequence conveys some important information, too. The first thing is that man, in his arrogance, presumes that he controls the planet and its future . Ghidrah: The Three Headed Monster reveals him “humbled” before the monsters. If man is to survive, and not suffer the same fate as the Martians, he will have to put his trust into beings -- monsters -- he considers enemies.

Secondly, the monsters dislike man as much as man dislikes them, apparently. More is made of this notion throughout the Godzilla franchise, actually. In Godzilla: Final Wars , for instance, we learn that Godzilla hates man -- and can’t forgive him -- because of his misuse of the planet, and because of all the “fires” (wars?) man has started.

Third, and finally, Godzilla, we learn here, seems to possess both a grumpy attitude (and the vocabulary of a sailor…) but also a strong moral barometer. He cusses and uses bad language when talking to Mothra, and that’s a funny moment. But more importantly, Godzilla refuses to fight until he sees what a total bastard Ghidrah really is. Ghidrah mocks and plays with poor Mothra and that action offends Godzilla’s sense of honor, even though Mothra has, in the past, defeated him.

Mothra is quite the smart creature too. No doubt, Mothra goes it alone intentionally, hoping that Godzilla will detect the level of the danger, and be drawn into the battle to save the planet. That seems to be precisely what happens.

Indeed, what seems to separate good monsters from bad monsters in this thoroughly enjoyable film is a sense of justice or honor.

Mothra, Godzilla and Rodan all demonstrate the capacity not merely for growth, but for cooperation. They are able to rally to a cause greater than themselves, in other words.

By contrast, King Ghidorah is really a berserker with no value system beyond destruction.

I suppose that the question that must be reckoned with involving Ghidrah: The Three Headed Monster involves changed premises or changed assumptions in the Godzilla franchise. Are audiences willing to embrace Godzilla the hero, over Godzilla the avatar of nuclear destruction?

And if so, is it a corruption of the franchise’s original idea?

Although on an artistic front, I do prefer the purity of the nuclear metaphor in Godzilla (1954), I must confess that on an emotional level, I love the idea of Godzilla as Earth’s (grumpy) defender. I love the big green monster as a hero, and as a friend to the human race. It may be a corruption of the original premise, but I do find Godzilla in these Showa "versus" films to be an appealing combination of innocent, tragic, and lovable.

One further quality of Ghidrah: The Three Headed Monster that may keep it from being a corruption of the original franchise intent and rather an evolution of key concepts is the example of Mars. The alien princess reports: “Centuries ago, the monster appeared in the skies of Mars. Within a month, the culture of Mars had been wiped out completely. The civilization on my planet had reached a stage of development which you people will not achieve for a long time…Today, because of the space monster, it is a dead world…dead and unpopulated.”

Encoded there is a direct corollary to the warning in Godzilla (1954).

Man has and will continue to achieve advances in terms of his technology, and his capacity for war. But if he brutalizes nature in that evolution, nature will have its revenge, and man will, in that conflict, lose.

Ghidorah, in essence, here takes on the role of Godzilla from the first film. He is Out-of-Whack Nature Personified: a threat that can’t be reckoned with in terms of technology or conventional war.

Ghidrah: The Three Headed Monster is such an imaginative and entertaining film not only because it features lovable and idiosyncratic monsters, but because it endows its monsters with a point of view that is not human-centric, and allows them -- in their own destructive way -- to settles matters based on those points of view.

To some, this approach of giving the monsters human personalities may seem silly or childish, but in a way, this creative choice perfectly expresses the childish nature of the Cold War conflict.

Are we really going to destroy the world because we can’t get along with each other? Can we stop kicking sand in each other's faces long enough to see that the planet needs our help?

September 27, 2025

40 Years Ago: The Twilight Zone (1985 - 1989)

Submitted for your approval (or lack thereof): the mid-1980s CBS remake of Rod Serling's classic 1960s anthology.

But, in a twist worthy of the famous land of shadow and substance itself, there's no Serling here (the legendary writer passed away in 1975); there's no moody black-and-white photography either (the series is shot in gauzy colors) and the bland stories -- with a few spiky exceptions (namely "Her Pilgrim Soul" and the intense "Nightcrawlers") -- don't quite feel like they would have passed muster had Serling been steering the ship.

Yes, you have just entered...The Twilight Zone....lite.

The 1985-1986 TV season actually saw several anthologies debut on network television, and none of them were particularly good.

"Proud as a Peacock" NBC offered the dreadful and over-hyped Spielberg production Amazing Stories, plus a remake of Alfred Hitchcock Presents. The latter venture offered the Master of Suspense himself (also long dead) vetting colorized introductions to new episodes, and we can surely be grateful, at least, that the new Zone did not choose the path of featuring Zombie Serling.

Despite the myriad flaws, this Zone lasted longer than the other anthologies named above, running for two uneven years on CBS before being shunted to syndication for a dreadful, low budget final season that is not merely Twilight Zone lite, but an insult to the heritage of the franchise.

But during the first two years on CBS, talented executive producer Phil De Guere and a stable of terrific writers made a serious, well-intentioned effort to update the classic series. Harlan Ellison was aboard (briefly) as a creative consultant, and well-known directors such as William Friedkin, Wes Craven and Tommy Lee Wallace helmed standout episodes. I watched this series religiously as a teenager (I was sixteen years old), and still have nostalgic memories. Honestly, you can tell everyone was giving the new series their all, but this new Twilight Zone has not -- for the most part -- aged well.

First off, I blame that fact on the uninspiring look of the series. Most of the episodes ("Nightcrawlers" excluded) resemble dreamy 1980s commercials for feminine hygiene products. There's no distinction, no originality in the visual component of the series, and so you can watch an episode and not be certain whether you're watching Simon & Simon or The Twilight Zone .

Even back in the black-and-white age, there was no mistaking the crisp, black-and-white canvas of the original Twilight Zone for anything else ( One Step Beyond , for instance, aired simultaneously, but it lingered more on long shots and featured fewer close-ups).

On the original Twilight Zone , the photography was as distinctive and the editing as staccato as Serling's trademark narration. Who can forget the brilliant photography and mise-en-scene in "Eye of the Beholder," or the careful balancing of shadow and light in "The After Hours?"

Separating The Twilight Zone from a distinctive, even trademark look was a terrible, perhaps fatal mistake. Now, I understand the series had to be shot in color for the 1980s, but there are ways -- even in color -- to forge visual distinction.

Witness the white-on-white minimalism of Space:1999, the lush fairy tale golds and bronzes of Beauty and the Beast , the grainy documentary look of the original Texas Chain Saw Massacre ; David Fincher's silver Seven , or even the various color palettes of such series as Prison Break, Firefly and Battlestar Galactica .

Something, nay anything, would have helped in this regard.

The 1980s Twilight Zone doesn't win plaudits for internal consistency either. Serling's opening and closing statements on the original series always let you know where you were, who you were with, and why you were there. There was no hedging. On the new Twilight Zone , some episodes included back and front end narrations, some had no narrations whatsoever ("Nightcrawlers"), and some - oddly - featured an opening narration but yet no closing narration ("A Little Peace and Quiet.") Often times, you couldn't tell what the hell the narration was talking about, either.

Charles Aidman narrated the new Twilight Zone (when there was a narration), and he did a fine job. His voice was sweeter, more whimsical more grandfatherly than the rat-a-tat machine gun-style of Serling.

Ironically, this was also the choice of Spielberg's Twilight Zone: The Movie (which went with another kindly voice, the one belonging to the great Burgess Meredith).

I respect these selections as a way not to imitate Serling's delivery, yet still hold serious reservations about the appropriateness of a kindly-sounding narrator. After all, The Twilight Zone is a place where the scales of justice are often righted; where the unheard are heard; where the cruel get comeuppance. Serling was sharp, witty and occasionally brutal in his approach to the narration. Thus, I would have preferred a similarly hard-edged narrator, a more aggressive, commanding voice. Why? When you have only fifteen minutes to vet a story, and you must gloss over certain aspects, it's good to have someone strong offering the punctuation. Otherwise, you start and end with a whimper, not a bang.

And at the end of every twisty Twilight Zone , you deserve that bang.

Rod Serling wrote something like ninety episodes of the original Twilight Zone. He was narrator for all of them. He also rewrote various episodes by other superb writers and produced the entire five year series. Considering his ubiquitous presence, it's fair to state that the Twilight Zone represented (primarily) his voice, his morality, his artistic sensibilities. Since he was gone by '85, the new series had no choice but to find its own voice.

And it is here, that I think the show failed to live up to his legacy.

Take for example, "Little Boy Lost." In this story, a woman photographer must make the choice between taking a new job or starting a family with her steady boyfriend. During the course of the story, she is haunted (on a photo shoot at the zoo) by the spirit of the child - a boy named Kenny - she ultimately chooses not to have. This is odd, because she's not even pregnant. (So to be clear, she doesn't have an abortion.) She's just a woman who decides it isn't the right time to start a family.

But she is "haunted" by the unborn child.

"All you have to do is want me," the boy tells her pitifully. Yikes! The sweet little boy (Scott Grimes) asks his would-be mother why she does not want to have him; why she does not love him, and it's all so madly extreme that you expect Pat Boone to show up and lecture us about the evils of abortion.

Yet, the same episode entirely lets the boy's would-be father, Greg, off the hook. Why isn't he haunted by the son he chooses not to have? Why just her?

A whiny little she-man and drama queen, Greg doesn't want to "compete" with the woman's career, so he makes a "choice" too...to break up with her.

So isn't Greg just as much to blame for the fact that this "little boy lost" isn't born? Poor, fragile snowflake.

Greg could have been a stay-at-home dad, his wife could have had her career, and they both could have had the child who wanted to live and be loved so badly. But no, the episode wears philosophical blinders about the man's role in this reproductive drama. Greg wants to make no accommodation in his own life to have that family and child. He just wants the woman to do it. And then she gets stuck with the ghosts of children future?

Off the top of my head, I can't think of even one 1960s Twilight Zone episode that is so blatantly sexist, or that has aged this poorly.

I mean, what's the real point here?

That every woman who chooses a career is actually killing a potential child? As I stated, the woman isn't even pregnant, all right? She just wants to be a professional photographer! Choosing to be childless is not the same as terminating a pregnancy. Choosing a career is not the same as having an abortion, yet "Little Boy Lost" can't make that critical distinction. As a result, the whole episode is icky. Greg is a self-righteous jerk, and the cute little kid is used as a bludgeon to make the lead character feel bad about a choice to live her life the way she wants.

Pack your bags, Zoners...we're going on a guilt trip! "Little Boy Lost's" ending narration backs away from the sexist interpretation of the episode as fast as it can, calling the story simply "a song unsung," "the wish unfulfilled," but it's too little, too late.

Watching this episode, I was reminded of a comment on Serling's particular and singular ethos, one made at his eulogy: "He showed us people maybe we'd rather not think about. But with that keen perception and sparse dialogue, he grabbed you...and told you in no uncertain terms that these people deserved at least a little victory, breathing space, someone to care about them."

"Little Boy Lost" is sort of the opposite of Serling's approach, isn't it? It judges. It makes a work-a-day character feel guilt, shame, and pain for something by rights she has no reason to feel guilty about. (Again, not pregnant, just wants a career...)

"Shatterday" is another signature episode that fails dramatically. And that's a surprise, especially considering all the name talent involved. Wes Craven directs a short story by Harlan Ellison (adapted by Alan Brennert). And the installment stars a very young Bruce Willis as one Peter J. Novins, an ostensibly argumentative man who "pushes" people until one day the world "pushes back." He's in a bar one evening when he telephones his apartment and a doppelganger picks up on the other end. Turns out this doppelganger is a better Peter J. Novins than he is; and that this enigmatic double is setting right all the mistakes of his life. Meanwhile, our Novins starts to fade away, "becoming a memory."

Personally, I love the ideas lurking in this vignette. I love the notion of a doppelganger; and the conceit that someone else might live your life better than you can. But, alas, "Shatterday" never actually dramatizes Peter Novins being a bad guy. The story picks up immediately before the terrifying phone call. As a result, we're told he is a "pusher" (meaning a nudge, I guess?) and a bad guy, but we never see it play out. All of Peter's actions in the episode are actually readily understandable, given that he believes an impostor is taking over his very life, aren't they? Wouldn't you push back too?

Allow me to make another invidious comparison to the original series. It would not have made sense, for instance, in the Serling episode "The Silence," if we had met the lead character there after he had made a bet to stop speaking aloud for a year's time. No, we had to see the loquacious central character babbling mindlessly and egotistically for a time, so we would understand the torture that he would go through in the course of the narrative. We had to understand the crimes of the jabberwocky before we got to see his sentence handed down by the mechanism of the twilight zone.

The same is true in "Shatterday"...we have no empirical evidence that Novins deserves what happens to him. And there's just no fun in seeing cosmic justice meted out if we don't understand the cosmic violation in the first place. One on-screen example of his pushy nature would have sufficed. And I don't mean sassing a bartender. That's not a Zone -worthy offense, if you ask me.

I hate to write negative reviews, especially about a series as good-intentioned and diverse in storytelling as this eighties Zone .

So let me accentuate at least one positive story that seems - at least to me - absolutely true to The Twilight Zone's spirit and heritage.

The story is titled "Wordplay," and it concerns a harried businessman (Robert Klein) who - because of a shake-up at the office - must learn the details of 67 new medical products in one week's time. All of these new-fangled products bear tongue-twisting names and are woefully technical. But then, something seems to change for the salesman. Language seems to melt right out for under him. Suddenly, it's not just the products he can't understand...it's everything! The word "lunch" is replaced with the word "dinosaur." The word "throw-rug" replaces the word "anniversary." Suddenly, this little guy trying to make his way faces an entirely new challenge, re-learning the English language. The end of the episode is simultaneously devastating and hopeful, as this forty-something year-old man sits down heavily on his son's bed, and begins going through first grade picture books...meticulously learning one new word at a time.

The thing of importance here: this "little guy" has been dealt a raw hand (as the little guy often is). But he's not going to stop fighting. He's not going to be defeated by it. "Wordplay" reminds us that the human spirit -- nay, the American spirit - is indomitable.

It's a terrific little tale; one that reflects how quickly the workplace was changing in the 1980s. (I remember, for instance that 1986 was the year my father began to learn Japanese.). So "Wordplay" was about something happening in the larger culture too; a pervasive fear that the old skills weren't going to be good enough in the newly emerging global workplace. "Wordplay" is a terrific show, and there were many such shows like it.

"Nightcrawlers," is another stand-out installment, one which concerns PTSD and the repressed horrors wrought by the Vietnam conflict. It depicts a compelling and nightmarish story set at a small diner just off the highway, a perfect setting for The Twilight Zone. It is blackest night -- with incessant rain pounding -- as the tale commences. A cocky police trooper (Jimmy Whitmore Jr.) who avoided service in Vietnam enters the diner, recounting to a waitress and the cook a harrowing story about the bloody aftermath of a strange motel shoot-out. He's clearly shaken by what he's seen.

As more travelers (including a family) seek solace from the violent storm, events in the diner take a weird turn. A nervous man named Price (Scott Paulin) arrives and is almost immediately revealed to be highly disturbed. He's a Vietnam veteran, you see, and was once part of an elite unit called "Nightcrawlers." Price was traumatized by one particular night mission against Charlie, one which cost the lives of several American soldiers. That night's horrific events remain so resonant with Price that he has developed an unusual power:the ability to manifest his terrible memories...in the flesh.

When Price sleeps (or is unconscious for any reason) his violent nightmares of 'Nam are granted substance and then run amok (which accounts for the motel massacre). Price and the trooper don't get along, and after a verbal confrontation, the trooper knocks Price out. His unconscious state paves the way for a violent dream that transforms this 1980s diner into a jungle landscape, one wherein armed soldiers are on a brutal mission to kill everyone. The episode culminates with a maelstrom of destruction and gun-fire, and the chilling promise that other veterans like Price are out there.. ones with the same destructive "power" and memories.

Boasting a heavily de-saturated and grainy look (the contrast was adjusted by Friedkin himself, according to the episode commentary), this is a Twilight Zone episode that looks more like Tobe Hooper's The Texas Chain Saw Massacre than it does the average installment of a popular TV series. This is an appropriate touch, because we're subconsciously reminded of authentic Vietnam War footage, and the grainy look it often boasts..

Utilizing just one set (the diner), Friedkin builds escalating tension by focusing on two visual flourishes; ones that he often deploys in his films: insert shots (to create a sense of detail, mood and texture), and extreme close-ups (to draw us into the world and troubles of the characters). On the former front, we get a tour of the diner's seemingly mundane terrain (including coffee cups filled with steaming coffee, cigarette lighters and the like). On the latter front, we are treated to a sustained, highly-upsetting close-up of the mad Price: red-eyed and psychotic; and growing ever more upset. This shot lasts a long time -- beyond all reason, actually -- and is highly disturbing. Friedkin's decision to hold the close-up (in conjunction with Paulin's committed performance) sells thoroughly the notion of this man's insanity.

The theme underlying Nightcrawlers is that for the men who witnessed atrocities and horrors in the Vietnman War, the conflict is never truly over. This notion was just bubbling to the surface when this episode of The Twilight Zone was made. It entered the American lexicon during the Reagan 80s as "Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder" (or PTSD) and never left, although a similar syndrome had once been known as "shell shock." Still, the idea was that we had a generation of men "coming home" in the late 1970s who had seen such horrible things that they could never again lead what we non-combatants consider a normal life. And worse, their problems were being ignored by the government, the citizenry, and even the media.

Remember what Freud stated so memorably: that "the repressed" returns as "symptoms." Nightcrawlers makes literal that notion. The only way Price can "exorcise" the demons of Vietnam is to produce those vivid demons in our reality. So what we have in Nightcrawlers is a genre metaphor for PTSD, down to the idea that - if left unexorcised - the violence unleashed in Vietnam will claim more victims here at home.

From the opening close-up of pounding rain to the anxiety-provoking visual distraction of bright lightning flashes and intermittent electrical black-outs, Friedkin makes this installment of The Twilight Zone feel authentically like an unpredictable powder-keg; one always on the verge of exploding. The personal fire-works between the highway trooper and Price are balanced well by the real (and disturbing) fireworks in the climax. The episode also generates a ubiquitous mood of deep unease.

So what's my conclusion about the '80s Twilight Zone here? What's my closing narration?

Perhaps just that you can't go home again.

That it's damned difficult to revisit a classic.

Especially when you don't necessarily have the arrows in your quiver to make your effort appear as stylish or as individual as what came before. The New Twilight Zone is thus a very mixed bag, and I suppose that's why even those viewers who "grew up with it" (myself included), find far more of interest (visually and thematically) in the Serling classic.

In the new series, you can spot a brief, almost subliminal flutter of Serling's iconic b&w visage in the opening credits, and that's all.

He's really only there briefly in spirit too. For all the criticism Night Gallery has received over the years, there's much more of the Serling spirit present in that series, in stories such as "The Messiah of Mott Street" and "They're Tearing Down Tim Riley's Bar." For that reason alone, Night Gallery feels more like an authentic follow-up to the original Twilight Zone than this mediocre, hit or miss, 1980s remake.

September 22, 2025

20 Years/Top 10 Posts #3: The Black Hole (1979)

[Originally published on the blog on April 21, 2009, this review has had over 35,000 (35K) views.

In 1979 and in the wake of Star Wars , Walt Disney Studios released a big-budgeted outer-space adventure called The Black Hole directed by Gary Nelson. It was the first movie in Disney history to be rated PG rather than G for general audiences. And it faced direct competition in theaters from the likes of Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), the long-awaited revival of the popular sci-fi TV series.Reviews of the film at the time were generally negative. The word from science-fiction magazines and writers was far less gracious. "Poisonous" might be a better descriptor.

Even three decades after the film's theatrical release reviewers were still deriding the movie in articles with titles like "Does The Black Hole still suck?"

The main point of contention for most science-based writers appears to be The Black Hole's flagrant ignorance about the laws of physics.

For instance, there appears to be a breathable atmosphere in outer space at the mouth of the black hole during the film's fiery finale.

And then there is Kate McCrae's (Yvette Mimieux's) famously mangled line of dialogue early on insisting that the Palomino and Cygnus vessels share the same mission: "to find habitable life" in space.

Technically, the learned scientist claims to be looking for "life" that people can inhabit or live in, and obviously that makes no sense. Had Kate simply said they were in search of "habitable worlds" or new "life forms," this wouldn't have been a concern. But there you have it: The Black Hole didn't do itself any favors by featuring a nonsensical line that should have been cut.

Despite such problematic moments, The Black Hole has survived and endured mainly on the affection of fans, I suspect, who first viewed the film in childhood and never forgot it. But is there more to The Black Hole than the inescapable gravitational pull of nostalgia? Exactly what are the film's merits? And why, thirty years on, does it remain such a polarizing and influential film?

Foremost among The Black Hole’s merits is its exploration of Manichean universe. More about that aspect of the film, and other positive attributes too, after the synopsis, below.

"If there's any justice at all, the black hole will be your grave!"

A small Earth space craft, The Palomino, has been charged with seeking out and discovering life in space. On mission day 547, however, the exploratory craft commanded by Captain Dan Holland (Robert Forster) discovers something else of interest: the largest black hole ever detected by man.

Intriguingly, the ship's robot, V.I.N.Cent (Vital Information Network Centralized) (Roddy McDowall) detects a stationary object near the black hole: the shrouded silhouette of a vast spaceship. The crew soon recognizes the craft as Space Probe One, or the Cygnus...the costliest fiasco in America's space program history.

The Cygnus's eccentric commander, Dr. Hans Reinhardt (Maximilian Schell) -- "one of the greatest space scientists of all time" -- refused Mission Control's recall order and the Cygnus has not been seen or heard from since.

Now, the quiescent Cygnus sits at the lip of the swirling black hole, miraculously resisting the pull of the devouring maw.

After acquiring some damage the Palomino lands on the Cygnus and the crew comes to learn the secrets of Reinhardt and his vast "death ship." V.I.N.Cent learns from another robot, Old B.O.B., that Reinhardt is insane; and that he lobotomized his mutinous human crew, eradicating their will and leaving the men and women of Cygnus mindless, spiritless automatons.

Also, Reinhardt has created a devilish red robot, Maximillian to help him carry out his plans to travel inside the black hole, inside “the mind of God.”

The survivors of the Palomino attempt to escape from Reinhardt even as the Cygnus sets a fateful course for the black hole. The escape attempt fails, and characters good and evil meet their fates inside the strange, mystical forces of the black hole

"Some cause may have created all this, but what caused the cause?" Mani was a Persian philosopher of antiquity (210-176 AD) who contended in his writings and teachings that that the universe was split into two opposing natures: Darkness and Light. He furthermore suggested that these warring forces fought their battles in the terrain of the human being. Man's body -- the material world -- was the world of sin and darkness. And man's soul -- his spirit side -- represented the Light. Roiling inside all of us is the never-ending conflict between these forces.

In The Black Hole, viewers can detect a number of Manichean ideas expressed in the dramatis personae and the narrative situations. This is especially so during the metaphysical journey through the black hole in the finale, a strange religious twist on the trippy denouement of Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey .

Mani believed that Evil had many faces...but that at all those faces were part and parcel of the same Evil, not different ones.

In The Black Hole, audiences see Maximillian and Hans Reinhardt as two faces of Evil (mechanical and human, respectively) throughout the film, but in their nightmarish last scene, these two evils literally join to become one: Reinhardt is subsumed inside the robot demon Maximillian.

Hauntingly, we see Reinhardt's frightened human eyes peering out from the machine's mechanical shell. This is our last close-up view of the characters, of twin evils welded together.

This strange inhuman union occurs inside the black hole, in a realm that resembles a Boschean vision of Hell, with hopeless souls (the spirit-less humanoids) trudging across a Tartarus-like underworld as flames lick at the bottom of the frame. High atop a hellish, craggy mountain, the Maximillian/Reinhardt Hybrid rules, like Milton's Lucifer.

In keeping with Manichean beliefs, this is visibly the realm of physical things: bodies, mountains, fire...materialism . It is no coincidence either that the production designs of the film have colored Maximillian, Dr. Hans Reinhardt and Hell itself in crimson tones.

This bond of red -- whether Reinhardt's uniform, Maximillian's coat of scarlet paint, or the strange illuminating light of Hell itself -- connects all of them as "the One Evil," not separate evils, as conceived by the ancient philosophy of Mani.

Contrarily, the four survivors of the Palomino expedition (Holland, McCrae, Pizer and V.I.N.C.ent) find not Hell in at the event horizon of the black hole, but rather a celestial cathedral of sorts. Their vessel, the probe ship, is guided through this realm of the spirit (not the body), by another soul...a white guardian angel. The protagonists temporarily seem to exit the world of the body, and the film reveals their thoughts -- past and present -- "merging" during a brief, strange scene involving slow-motion photography.

What this scene appears to portend is that the three humans -- and robot (!) -- have been judged by the cosmic, Manichean forces inside the black hole and found to be above "sin," hence their journey through the long, Near Death Experience-style "light at the end of the tunnel" and subsequent safe re-emergence back into space.

Instead of remaining trapped in a physical Hell (like the Reinhardt/Maximillian hybrid), the probe ship and those aboard it pass through the gauntlet of "spirituality" where nothing -- not even sin -- can escape, and arrive safely in what appears to be a new universe. The closing shot of the film finds the probe ship on course for a giant white sun...a beacon of light and hope, and perhaps even a new beginning for the human race (and again, oddly enough, robot-kind...).

Reinhardt's final utterance before entering the crucible of the black hole is simply a mumbled..."all light."

This might be an allusion to William Wordsworth's poem, An Evening Walk Addressed to A Young Lady: "all light is mute amid the gloom," It may be Reinhardt's (too late...) recognition of the fact that just as he has squelched out all light in the souls of his crew so will the black hole mute out his spiritual light...sending him into utter, eternal darkness.

Whether intentionally or not, the climactic and symbolic final moments of The Black Hole -- long a subject of debate among the movie's detractors and admirers -- fit the philosophical tenets of Manicheism perfectly, positing for audiences the metaphor of devouring black hole as a spiritual testing ground or judgment day : one where humans understand that the secret of creation...is man's spirituality; his sense of morality .

So the use that the movie ultimately puts the black hole to is not scientific at all , but rather spiritual or even religious. For some viewers, that may simply be a bridge too far in belief. For other', it's a recognition, perhaps, that man must ultimately reckon with himself, especially when facing what Reinhardt explicitly terms the Mind of God.

Another, all-together different way to appreciate The Black Hole is as a virtual compendium of Jules Verne concepts and characters as they appeared in both literature and film history, only translated from the sea to the realm of outer space.

For instance, Hans Reinhardt is clearly a futuristic version of Captain Nemo. Like his literary predecessor, Reinhardt is a figure associated with a magnificent and highly-advanced vessel. In this case, that vessel is Cygnus not Nautilus.

But consider that both Reinhardt and Nemo also grant their "guests" (prisoners?) an extensive tour of those ships, with special attention paid to technological innovation. In the book 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Nemo created a ship that ran on electricity; in the film it was atomic energy that powered Nautilus. In The Black Hole , Reinhardt discusses his creation of a limitless power source called "Cygnium" after his beloved ship. This is the thing that allows his ship to resist the forces of the black hole.

Furthermore, both Nemo and Reinhardt are defined as characters in terms of their ingenious ability to live off the resources at hand; off the sea or off outer space, as it were. In both 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea and The Black Hole , the Nemo figure explains this fact in a dining room setting to his guests.

In the former tale, Nemo serves Aronnax and the others delicacies acquired from the abundant sea. In the latter narrative, Reinhardt discusses his personal hydroponic garden, which has grown all of his food.

Again, it's intriguing that both dining rooms (on the Nautilus and Cygnus respectively...) genuflect to the traditions of the past in terms of decor (candelabras, crystal glass ware, a naval telescope, statuary...) while the remainder of rooms on each ship suggest an overtly technological future.

As is the case in Mysterious Island (1961) and 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea (1954), The Black Hole's screenplay explicitly debates the essential, conflicted, and perhaps Manichean nature of Hans Reinhardt with the very words we've seen utilized before in relation to Nemo: "insane" and "genius."

Similarly, like Nemo, Reinhardt is a man who has left mankind behind, dwelling in a realm of exile. Yet there's an important distinction here: Reinhardt is not an anti-hero like Nemo. He is not a hero of any kind . Reinhardt is actually an egomaniac who has robbed his crew of their very souls in his quest to probe the mysteries of God.

Reinhardt is so narcissistic in fact, that he has forced his soulless crew members to wear reflective, mirrored face-plates over their own visages. What does this mean in practice? When Reinhardt looks at his crew, he sees only his own face reflected back. This is arrogance and vanity far beyond anything which Nemo ever aspired to or considered.

It seems clear that if the film Mysterious Island transforms Captain Nemo into a more palatable, rational 1960s "man of peace," Reinhardt is a post-Watergate, post-Three-Mile-Island, post-Vietnam figure of corruption, avarice, and madness. He is Nemo, perhaps, but Nemo skewed heavily to the dark side, instead of to the light.

The remaining characters in The Black Hole also seem to have distinct corollaries with those found in Verne's works.

Most clearly, Alex Durant (Anthony Perkins) is a dedicated man of science and one in " search of his own greatness." He thus seems a skewed version of the noble Professor Aronnax (another French name...) from 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea . Aronnax clearly boasted a healthy moral compass, however, and by comparison Durant seems mesmerized, star-struck, and overcome by the dreams and accomplishments of Reinhardt. Again, we see a character from Verne's universe skewed to the dark side. This is appropriate given the increasingly low public approval of scientists as the 1970s wore on.

Harry Booth is very much the same story. A journalist, he could very well be the "war correspondent" Spillit from the movie Mysterious Island , only once more decidedly tweaked to seem more negative: this time emerging as a treacherous coward. Both Mysterious Island and The Black Hole feature confrontational scenes in which the Captain Nemo figure reveals his disdain for the reporter. Perhaps it is because the reporter, in both situations, represents the interests of the population back home and their "earthly" concerns: the so-called "unwashed" masses.

The similarities between Verne's world and the world of The Black Hole don't end with character descriptions.

Consider that a crew funeral plays an important role in both the Fleischer version of 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea and also the Disney space film.

In 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea , the underwater funeral is the first thing Aronnax sees of Nemo's nature, crew, and world. In The Black Hole , Holland spies a humanoid funeral and garners the first clue about the nature of those "robots."

The dangerous black hole itself seems to represent the ocean-bound whirlpool, the deadly maelstrom that destroyed the Nautilus in Verne's literary masterpiece, serving the same function in The Black Hole .

Finally, it is impossible not to notice that Reinhardt and Nemo share very similar death scenes in both The Black Hole and the movie version of Mysterious Island. In The Black Hole , Reinhardt is crushed by a falling view screen, and we see him die with his (bulging...) eyes wide open. In Mysterious Island , Nemo also dies with eyes open, after a crushing beam has fallen on his torso.

While one or two of these Verne-style visuals, narrative points, characterizations or story traits might simply prove a coincidence, there is such a preponderance of them in The Black Hole that it becomes incumbent on us to view the film as almost literally a post- Star Wars adaptation of 20,000 Leagues Under The Sea . It is one that has updated the "fantasy" setting from the bottom of the sea to the most distant reaches of outer space; one that has re-fashioned the anti-hero Nemo as a more cynical, more corrupt 1970s-style figure. It is also one that has replaced atomic age fears of self-annihilation, with the 1970s "Me Generation" fear of personal oblivion and spiritual malaise.

Leaving behind Manichean interpretations and thoughts on its Jules Verne-ish qualities, The Black Hole impresses on another field of play. I believe it was Nicholas Meyer, director of Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan and The Undiscovered Country who discussed the idea that many of the greatest works of art leave some sort of "gap" for the percipients to fill in for themselves. When we listen to music, our mind supplies the images. When we gaze at a great painting, our mind fills in movement or "life," perhaps. And in great, artistic films some gaps in motive, narration, and explanation are left open so that we -- the viewers -- can bridge that gulf with our own imagination. We thus engage the material not with passive disinterest, but with active thought.

For all of its flagrant ignorance regarding science and physics, The Black Hole is positively filled with bizarre, almost throwaway moments of remarkable imagination and implications. For instance, late in the film, after Maximillian has disemboweled Dr. Durant with his spinning propeller blades, Dr. Reinhardt approaches Kate with extreme fear in his eyes. He begs her in a whisper (so that his machine minion cannot overhear...): "Protect me from Maximillian."

There is no explicit follow-up to this moment; no real mention of it later in the film, just this urgent, persuasive conversational alleyway (lensed in medium shot) that suggests -- for a fraction of a second -- that Reinhardt fears his own Frankenstein monster. That it is the hovering, scarlet cyclops named Maximillian who rules the Cygnus, not the fallible, eccentric human being. It is as though Maximillian is Reinhardt's Id, only physically separated from him, acting of his own volition.

We might extrapolate that this single line of dialogue helps better to explain Reinhardt's final disposition -- his personal Hell. Inside the black hole, he is forced to join with Maximillian, to go inside the beast and dwell there for eternity. We know from that single, odd line of dialogue that Reinhardt fears such a thing...a monster he can no longer control, but that controls him. Where many people believe that in death we leave our bodies for non-corporeal spirit forms, the Manichean truth of Reinhardt's afterlife is that the Darkness has prevailed and he will be trapped in a metal shell for eternity. There is no ascension for him because of his sins. We know this later when we hear (inside the probe ship), his repeated and tortured calls for "help."

There are several odd little moments like this one in The Black Hole that are worthy of mention and analysis.

Many critics picked on V.I.N.Cent -- the Cicero-quoting platitude machine -- as some kind of R2-D2 rip-off. They complained about his mode of communication too. Throughout the film, the robot speaks almost entirely in proverb and platitudes, throwing out one after the other in clearly...mechanical fashion. One can look at V.I.N.C.ent's mode of expression as a result of bad writing, or as something a bit more interesting. That V.I.N.C.ent apparently sees his world in terms of metaphors suggests that he possesses some sense of understanding of life beyond the literal.

Again, this uncommented-upon touch plays into the ending of the film: the robot boasts a "soul," apparently, and survives the crucible of judgment inside the black hole since he -- a machine -- is put there on equal footing with Dan, Kate and Charlie Pizer...and we are privy to his thoughts. Even his throwaway line about disliking the company of robots seems to indicate that V.I.N.C.ent for all his lamentable cartoonish qualities...is more than mere robot.

Kate is able to communicate telepathically with this distinctive robot, another indicator that V.I.N.cent is more than the sum of his parts.

And that realization brings us to another interesting line of dialogue laden with implications: while on the Cygnus V.I.N.C.ent reveals the specifics of something called "Project Black Hole," a governmental operation which sent robots to the event horizon and telepathically recorded their responses to the strange events occurring there.

Again, this idea has no play in the remainder of the film, but it raises all kinds of notions. Are robots the slaves of man in the future envisioned by The Black Hole? Or are they an artificial life form slowly developing sentience? And if Project Black Hole existed a long time ago as V.I.N.C.ent indicates, then did Reinhardt know of it? Did he actually create Maximillian to house his body (knowing a robot could survive there...) in case of emergency? Was Maximillian's armor but Reinhardt's second fallback measure, behind the probe ship?

It's very easy to gaze at many moments in The Black Hole as being mere "fun with robots," or other such nonsense, but if one returns to the argument about Manichiesm, one might see how Maximillian symbolizes the realm of the body/darkness and V.I.N.C.ent seems to evolve beyond that, achieving the level of the spiritual/Light. The movie is thus about not only about man, but the evolution of his machines into self-aware beings who are expected to conform to a moral compass.

Another thing that The Black Hole does remarkably well is hint at the larger universe of the characters. You see that in V.I.N.C.ent's casual mention of Project Black Hole, but elsewhere as well.

Early in the film, the crew of the Palomino attempts to identify the Cygnus on a holographic projector, and we are treated to a visual litany of missing ships. Arcturus 10 from Great Britain, Liberty 7 from the U.S., Russian Series 5 Experimental Space Station and the French Sahara Module. Eventually the crew hits on the Cygnus, but not before we get a sense of how "dangerous" outer space can be in this particular universe. This gives a much-needed context to the main storyline, that space is a dangerous and mysterious realm.

Indeed, another part of the film's longevity derives from the fact that it possesses this creepy, almost gothic texture of dread and terror. The humanoids are like faceless medieval monks, and Maximillian is deliberately a devil in red armor. The Cygnus itself is a vast, empty, “Flying Dutchman” of ghosts, loaded with mysteries (like limping robots, and eerily empty crew quarters...) that lurk around every corner.