John Kenneth Muir's Blog, page 6

June 21, 2025

40 Years Ago: Lifeforce (1985)

"Lifeforce may come to be considered a noteworthy science-fiction film precisely because it is so relentlessly unsentimental and edgy. This film displays a sensibility so odd, so unfamiliar, that it may prove one of the most subtly original sf films of the 1980s...[T]he film has something to offend almost everyone but offers much for serious analysis."

- Brooks Landon, The New Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, 1988, page 276.

The Cannon film -- based on a novel by Colin Wilson called Space Vampires -- was a gigantic box office failure upon release, and yet a generation of admirers quickly found it on home video...and the film became legendary in some circles.

I admire Lifeforce so deeply and so thoroughly because I feel that, like Hooper's The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1973), the film goes (far) out of its way to shock and transgress, leaving no taboo related to its subject matter -- sex -- untouched.

Hooper is never one for Hollywood-styled movie decorum, and I've always found his subversive, bracing takes on horror tropes (vampires, ghosts, cannibals) authentically disturbing because of that very fact. His movies, while speaking trenchantly in the language of film grammar, almost universally lack...tact. You just don't know where this director is going to take you, or what he is going to show you. As fellow horror maestro Wes Craven famously noted, a "filmmaker like Tobe Hooper can convince you you're really at risk in a theater." (Entertainment Weekly, October 23, 1992, page 41), and that is the essence of Hooper's ethos as far as I'm concerned.

In short, Lifeforce is a big-budget, colossal-in-scope meditation on the consequences of sex in all sizes, shapes, forms, and perversions. In part, the film is a straight-faced walking-tour of late 20th century sexual proclivities, from voyeurism to masochism, from homosexuality to fetishistic obsession. Among other things, Lifeforce is about your deepest, most personal desires taking over, and that content is reflected in the film's dazzling, jaw-dropping form.

Even in the development of this core idea about sex, Hooper chooses incredibly unconventional pathways for his epic horror film. In Lifeforce, the film's sexually-transmitted space vampire disease becomes a zombie epidemic that transforms London into something half-way between a George Romero Living Dead film and the weirdest orgy in cinematic history.

Some reviewers viewed this ending as a mistake, an out-of-character u-turn for the film and a lapse in serious tone. Yet if you're a longstanding Hooper aficionado you may realize that the strange climax of Lifeforce boasts clear antecedents in films such as Poltergeist as a kind of post-narrative, almost anti-narrative detour. Remember, L.M. Kit Carson called Tobe Hooper the "no deal" kid, and that's the go-for-broke, breathless quality of Lifeforce that keeps me watching it more than a quarter century later.

Given the weird and controversial subject matter here and the blunt vetting of it by a confident, at-the-top-of-his-game Hooper, perhaps it is only natural that the film so divided critics. Bruce Eder of Video Magazine called Lifeforce (possibly) "the last great science fiction film to come out of England," while film scholars Bill Warren and Bill Thomas (in American Film: "Great Balls of Fire, March 1986, page 70) felt the film got "the spectacle and weirdness right" but that the film lacked a "much-needed sense of humor."

Others were less open to the Lifeforce experience. Janet Maslin in The New York Times jokingly termed the film "sterile," while People Magazine's Ralph Novak found it "tiresome." Cinefantastique even termed Lifeforce (in October 1985) "an object lesson in failure." Space Vampires author Wilson called Lifeforce "the worst movie ever made."

I can't know this for certain, but I suspect that a great many of these critics actually found the Hooper film offensive. Visually and narratively offensive. They were responding to the decorum-shattering images and plot-line.

But of course, being offensive is kind of the point in the horror genre, isn't it? Horror can show us things that mainstream movies can't, or won't. A truly strong horror film will rock the audience back on its heels so it is unprepared for what comes next. And in that state, a talented director can mold audience expectations and emotions like putty.

I would suggest that's exactly Hooper's accomplishment in Lifeforce . Here he corrals such controversial visual elements as rampant frontal nudity and extreme gore to craft the feeling of a world rapidly spiraling out of control, consumed by an unquenchable desire in our very blood. Replete with narrative blind alleys and daring, unconventional imagery, plus controversial subject matter, Lifeforce establishes again that Hooper is the genre's most underrated, underestimated genius, a legitimate provocateur extraordinaire.

"I'm fascinated by death itself. What happens as we die, when we die. What happens after we die..."

As the space shuttle Churchill -- a joint American/European space exploration venture -- nears Halley's Comet, something alien and colossal is detected inside. It's a vessel 250 miles long and two miles high.

Mission commander, Colonel Carlsen (Steve Railsback), leads a small team on a mission inside the derelict. There, he finds a crew of dead bat-creatures, and more mysteriously, three perfect and naked humanoids: two men and a gorgeous woman (Mathilda May).

Sometime later, on Earth, a European Space Agency discovers the Churchill limping home from its rendezvous with the comet, unresponsive to communication attempts. A rescue team finds all crew aboard dead, save for the three nude aliens. These creatures are promptly brought back to Earth for study, and the Space Girl soon awakes. She drains the "lifeforce" from a guard, and then escapes from the facility.

Soon, soul survivor Carlsen's escape pod makes a landing on Earth, and he teams with England's stoic Colonel Caine (Peter Firth) and Dr. Hans Fallada (Frank Finlay) to locate the Space Girl before she can pass her vampiric disease on to more unsuspecting humans.

While Carlsen and Caine track the Space Girl to a home for the criminally-insane outside of London, Dr. Fallada determines that the Girl and her brethren from the stars may be the source of Earth legends of vampires. Meanwhile, the Space Girl has been leading Carlsen and Caine on a very lengthy goose chase as the vampire "infection" multiplies and sweeps London.

Now Carlsen must confront the "feminine in his mind," as the Space Girl begins to deliver disembodied human souls or life-force to her orbiting starship...

"In a sense we're all vampires. We drain energy from other life forms. The difference is one of degree."

The societal context bubbling beneath the surface of Lifeforce (1985) is the rising of the "wasting disease" of the mid-1980s, soon-to-be identified as AIDS and recognized as an epidemic that impacts individuals of all sexual persuasions.

A comparison to Carpenter's The Thing is illustrative here. Both horror films of the 1980s involve a shape-shifting evil passed from person-to-person, very much like a sexually transmitted disease.

In the case of Lifeforce , the metaphor is more overt, since sexual hypnosis/coupling -- with an alien vampire -- is actually the primary mode of disease transmission. Invisible to conventional medical and visual detection, the alien infection in both of these films subverts people, unbeknownst to their neighbors. Affected individuals appear normal to all outward appearances, healthy even, but in fact they are carriers of a secret, dreadful death.

In terms of context, "disease" was one of the biggest bugaboos of the 1980s horror cinema, featured in films like Prince of Darkness (1987) as well as The Thing . The point was, largely, that in the superficial world of Olivia Newton John's Physical , Jane Fonda's Aerobic Workout, or Jamie Lee Curtis's Perfect (1983), the worst thing that could happen to a person would be to discover that his or her beautiful, athletic lover was actually carrying a hidden disease, one that could sabotage the flesh, and also an individual's carefully cultivated physical beauty.

In particular, some film scholars have suggested that both The Thing and Lifeforce feature a substantial same-sex undercurrent.

In The Thing, a deadly plague passes in the blood from person-to-person in an exclusively all-male setting: an Antarctic research outpost.

In Lifeforce, the argument goes, there are also significant male-to-male couplings. First, there is the jarring and impassioned kiss between Carlsen and Armstrong (Patrick Stewart), an embrace that is inarguably homosexual in form (even though May's Space Girl inhabits Armstrong's mind).

Secondly, a male victim of the Space Girl awakens on the operating table early in the film and mesmerizes a male pathologist. He quickly converts the poor physician into one of the disease's transmitters. As Edward Guerrero described the scene in " AIDS as Monster in Science Fiction and Horror Cinema :"

"The film foregrounds homosexual transmission by focusing on the ravished bodies of male victims and by depicting in a key, horrific autopsy scene, an emaciated young male corpse who -- with outstretched arms -- hypnotically draws one of the male pathologists into a fatal energy draining, homoerotic embrace and kiss...the camera moves through...close-ups of the faces of the doctors trapped in the surgery as they register various reactions to the act and its gay proclamations, ranging from frozen panic and disavowal to an ambivalent fascination."

Guerrero also writes that Lifeforce's grisly corpses -- which receive considerable on-screen attention -- are depicted as young and starkly emaciated, resonant with the media's description in the 1980s of the "wasting" effects of the AIDs virus.

I agree with Guerrero's supposition that there is a homosexual component to be excavated in Lifeforce, but I don't agree that it is foregrounded in the film proper.

Rather, it's just one dish on the smorgasbord.

I submit that Lifeforce is actually a more general morality play and warning against succumbing to all manners of wanton sexual urges. Early in the film, Carlsen faces this weakness: "She killed all my friends and I still didn't want to leave. Leaving her was the hardest thing I ever did," he declares. What he fears is being unable to control himself, unable to assert his rational mind over his body's sexual desires.

Taken in its entirety, the film plays no favorites, targets no one lifestyle, and homosexuality is merely one aspect of the universal human sexual equation. As I wrote above, the film is a tour through sexual proclivities of all types.

In charting this trajectory Lifeforce is actually as bold -- perhaps brazen -- about depicting sexual issues as The Texas Chainsaw Masssacre is about recording horrid, graphic violence. Throughout the film, Hooper deploys one powerful symbol to represent "lust" in the human animal: the Space Girl. Hooper parades this character about naked throughout the film in an absolutely immodest sense. The film breaks ground and shatters decorum in this key approach. And the content, a so-called tour of human sexual issues, reflects the chosen form. We are constantly reminded, in the nude persona of May, that Lifeforce concerns sex.

To wit: when Carlsen first boards the alien spaceship early in Lifeforce , he discovers that the interior chamber of the spaceship is something akin to a massive birth canal. The similarity is so telling, in fact, that Carlsen states unequivocally, "I feel like I've been here before." The tiny astronauts probing deep into the long tunnel to the hidden chamber beyond this organic-looking tube may as well be tiny sperm navigating a woman's uterus.

When the astronauts reach the hidden chamber, they discover May's Space Girl there, and their instant lust "births" her in some sense When she is returned to Earth, she returns, importantly, as a creature of lust herself; a child of the astronauts' overwhelming desire. She is "the feminine" of Carlsen's mind and begins her exploration of human sexuality, according -- it seems at times -- to his subconscious desires.

Consider, for a moment, the specific events portrayed in the Space Girl's walkabout outside of London.

She encounters sex as casual infidelity (with a married man in a parked car).

She experiences male-to-male contact in the body of Armstrong in his homosexual kiss with Carlsen. If she is part of Carlsen's mind, she must believe that some part of him desires this "form" of sexual encounter.

For a time, the Space Girl's consciousness also enters the body of a nurse who is described in the dialogue as a "devoted masochist." This woman takes great joy in the fact that Carlsen must beat information out of her. She showcases no modesty about this desire, and again, Carlsen showcases no trepidation about engaging in sadistic behavior to get the information he needs, and also provide her pleasure.

Even the staid Colonel Caine acknowledges his own sexual side when he notes that he is a natural voyeur, and quite willing to watch Carlsen rough-up the masochist nurse.

Finally, even sex as grounds for political scandal is briefly touched upon here when the film's prime minister spreads the sexual infection to his unsuspecting secretary.

Beyond this Alice in Wonderland tour of human sexuality, there is also all the fiery, heterosexual coupling between Railsback and May, a devastating relationship that ends, incidentally, in a climactic double penetration (by sexual organs and by a fatal stab in the "energy center" from a sword blade.)

Considering the wide breadth of indiscriminate, unloosed sexual behavior that Lifeforce visualizes, it is no surprise that the film relies upon the vampire as a villain. Traditionally, vampires are alluring, magnetic and filled with strange, unsated appetites. They thrive on blood and can transmit their own illness to unaware victims. Their kiss brings only death. But the space vampires of the film steal souls, not merely blood, and that's an important distinction in Hooper's allegory about the perils of promiscuous, wanton desire let loose in the Age of AIDS.

What is at stake when you let go so fully? When you shed all control and give in to your most base desire? Is your soul at stake? Or just your life?

Given such questions, the film ends appropriately in a grand British cathedral, a sanctuary for the pious, one would assume.

There in the church, the infected bodies of the sexually depleted await their judgment...spent and sick. Their souls are carried away on a ray of light which focuses itself on the altar: the very fulcrum of all sermons and messages about chastity and abstinence.

Consider the symbolism. These souls have been dispatched to a nether realm, the alien spaceship, and it is surely an allegory for Hell. In terms of visuals, this is a moral conclusion, a literalization of Christian puritanism. Indulge in indiscriminate sex, and if it doesn't make you sick, it's still going to cost you your soul, and you'll dwell forevermore in Hell.

It's a harsh comment, perhaps, but given what some might view as the rise of casual sex in the culture (following the era of Looking for Mr. Goodbar [1977]) and the dawning of AIDS awareness and paranoia in the early 1980s -- which proved so strong it turned even James Bond into a one-woman-kind of guy -- it's an accurate reflection of what people seemed to fear at the time. Carlsen's triumph at the end of the film is that he controls his desire again, and kills the Space Girl. His victory asserts that human kind is not out of control, in thrall to subconscious appetites and desires.

If Lifeforce is an examination and perhaps even condemnation of promiscuous, rampant sexuality, it is also a supreme, unsettling entertainment. It surprises constantly, and features a number of nice homages to classic horror cinema. I mentioned George Romero's Dead cycle, but Lifeforce also harks back to an older, British tradition: the Quartermass and Nigel Kneale's legacy. There, aliens from space were the source of our mythology. They came to Earth and were reckoned with in terms of scientific and military solutions. Lifeforce is very much the same animal...plus huge heaping helpings of sex and visual effects. I also happen to believe the film does possess a sense of humor, but that it makes those jokes straight faced, in a staccato rat-a-tat-tat of overlapping dialogue.

Lifeforce is about a "destroyer of worlds," but if you read the film closely, it suggests that our desires -- and our inability to resist them -- is the very thing that could destroy humanity. It's a point that's easy to lose sight of when you're watching Mathilda May cavort about with no clothes on.

But in terms of May, Hooper's directorial acumen, and the sexually-charged plot line, Lifeforce is absolutely impossible to resist.

June 20, 2025

20 Years/Top 10 JKM Posts #6: (And 50 Years Ago!) Jaws (1975)

A modern film classic now half-a-century old, Jaws (1975) derives much of its terror from a directorial approach that might be termed "information overload."

Although the great white shark remains hidden beneath the waves for most of the film -- unseen but imagined -- director Steven Spielberg fills in that visual gap and the viewer's imagination with a plethora of facts and figures about this ancient, deadly predator.

Legendarily, the life-size mechanical model of the shark (named Bruce) malfunctioned repeatedly during production of the film, a reality which forced Spielberg to hide the creature from the camera for much of the time. Yet this problem actually worked out in the film's best interest. Because for much of the first two acts, unrelenting tension builds as a stream of data about this real-life "monster" washes over us.

In short, it's the education of Martin Brody, and the education of Jaws ' audience.

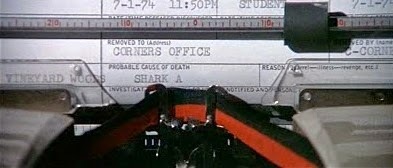

After a close-up shot of a typewriter clacking out the words "SHARK ATTACK (all caps), images, illustrations and descriptions of the shark start to hurtle across the screen in ever increasing numbers. Chief Brody reads from a book that shows a mythological-style rendering of a shark as a boat-destroying, ferocious sea monster.

Another schematic in the same scene reveals a graph of shark "radar," the fashion by which the shark senses a "distressed" fish (the prey...) far away in the water.

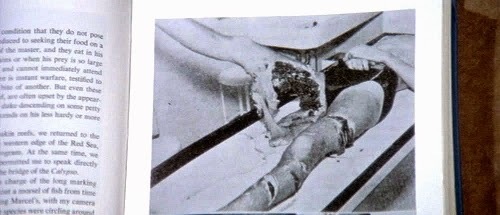

Additional photos in the book -- and shown full-screen by Spielberg -- depict the damage a shark can inflict: victims of shark bites both living and dead. These are not photos made up for the film, incidentally, but authentic photographs of real-life shark attack victims.

Why, there's even a "gallows" humor drawing of a shark (with a human inside its giant maw...) drawn by Quint at one point, a "cartoon" version of the audience's learning.

Taken together, these various images cover all aspects of shark-dom: from reputation and lore to ability; from a shark's impact on soft human flesh, to the macabre and ghastly.

This information overload about sharks also comes to Brody (the audience surrogate) in other ways, through both complementary pieces of his heroic triumvirate, Hooper and Quint, respectively.

The young, enthusiastic, secular Hooper first becomes conveyor of data in his capacity as a scientist.

Hooper arrives in Amity and promptly performs an autopsy on shark attack victim Chrissie Watkins. He records the examination aloud into a tape recorder mic (while Brody listens). Hooper's vocal survey of the extensive wounds on the corpse permits the audience to learn precisely what occurred when this girl was attacked and partially devoured by a great white shark.

Hooper speaks in clinical, scientific terms of something utterly grotesque: "The torso has been severed in mid-thorax; there are no major organs remaining...right arm has been severed above the elbow with massive tissue loss in the upper musculature... partially denuded bone remaining..."

As Brody's science teacher of sorts, Hooper later leads the chief through a disgusting (and wet...) dissection of a dead tiger shark (one captured and believed to be the Amity offender). Again, Hooper educates not just Brody; he educates the audience about a shark's eating habits and patterns. All these facts -- like those presented by illustrations in the books -- register powerfully with the viewer and we begin to understand what kind of "monster" these men face.

Later, aboard the Orca, Quint completes Brody's learning curve about sharks with the final piece of the equation: first-hand experience.

Quint recounts, in a captivating sequence, how he served aboard the U.S.S. Indianapolis in 1945. How the ship was sunk after delivering the Hiroshima bomb, and how 1100 American sailors found themselves in shark-infested water for days on end.

As Quint relates: "the idea was: shark comes to the nearest man, that man he starts poundin' and hollerin' and screamin' and sometimes the shark go away... but sometimes he wouldn't go away. Sometimes that shark he looks right into ya. Right into your eyes. And, you know, the thing about a shark... he's got lifeless eyes. Black eyes. Like a doll's eyes. When he comes at ya, doesn't seem to be living... until he bites ya, and those black eyes roll over white and then... ah then you hear that terrible high-pitched screamin'. The ocean turns red, and despite all the poundin' and the hollerin', they all come in and they... rip you to pieces."

This testimony about an eyewitness account is not the only "history" lesson for Brody, either. Brief reference is also made in the film to the real-life "Jersey man-eater" incident of July 1 - July 12, 1916, in which four summer swimmers were attacked by a shark on the New Jersey coast.

This "information overload" concerning sharks -- from mythology and scientific facts to history and nightmarish first-person testimony -- builds up the threat of the film's villain to an extreme level, while the actual beast remains silent, unseen. When the shark does wage its final attack, the audience has been rigorously prepared, and it feels frightened almost reflexively.

Spielberg's greatest asset here is that he has created, from scratch, an educated audience; one that fully appreciates the threat of the great white shark. And a smart audience is a prepared audience. And a prepared audience is a worried one. We also become invested in Brody as our lead because we learn, alongside him, all these things. When he beats the shark, we feel as if we've been a part of the victory.

Another clever bit here: after all the "education" and "knowledge" and "information," Spielberg harks back to the mythological aspect of sea monsters, hinting that this is no ordinary shark, but a real survivor -- a monster -- and possibly even supernatural in nature (like Michael Myers from Halloween ).

Consider that this sea dragon arrives in Amity (and comes for Quint?) thirty years to the day of the Indianapolis incident (which occurred June 30, 1945). Given this anniversary, one must consider the idea that the shark could be more than mere animal.

It could, in fact, be some kind of supernatural angel of death.

Now, in 1975, this shark arrives on the home front just scant months after the fall of Saigon in the Vietnam War (April 30, 1975) -- think of the images of American helicopters dropped off aircraft carriers into the sea.

This shark nearly kills a young man, Hooper, who would have likely been the same age as Quint when he served in the navy during World War II.

Does the shark represent some form of natural blow-back against American foreign policy overseas? I would say that this idea is over-reach, a far-fetched notion, if not for the fact that the shark's assault on the white-picket fences of Amity strikes us right where it hurts: in the wallet; devastating the economy.

It isn't just a few people who are made to suffer, but everyone in the community. And that leads us directly to an understanding of the context behind Jaws .

President Nixon resigned from the White House on August 9, 1974...scarcely a year before the release of Jaws.

He did so because he faced Impeachment and removal from office in the Watergate scandal, a benign-sounding umbrella for a plethora of crimes that included breaking-and-entering, political espionage, illegal wire-tapping, and money laundering.

It was clear to the American people, who had watched the Watergate hearings and investigations on television for years, that Nixon and his lackeys had broken the law, to the detriment of the public covenant. It was a breach of the sacred trust, and a collapse of one pillar of American nationalism: faith in government.

In the small town of Amity in Jaws , the Watergate scandal is played out in microcosm.

Chief Brody conspires with the town medical examiner, at the behest of Larry Vaughn, the mayor, to "hide" the truth about the shark attack that claimed the life of young Chrissie.

Another child dies because of this lie.

We are thus treated to scenes of Brody and the town officials hounded by the press (represented by Peter Benchley...), much as Nixon felt hounded by Woodward and Bernstein and the rest.

We thus see a scene set at a town council meeting which plays like a congressional Watergate hearing writ small, with a row of politicians ensconced for a long time before an angry crowd. The man in charge bangs the gavel helplessly.

These were images that had immediate and powerful resonance at the time of Jaws. If you combine the "keep the beaches open" conspiracy with the Indianapolis story (a story, essentially, of an impotent, abandoned military) what you get in Jaws is a story about America's 1970s "crisis of confidence," to adopt a phrase from ex-president Jimmy Carter.

Following Watergate, following Vietnam, there was no faith in elected leaders, and Jaws mirrors that reality with an unforgiving depiction of craven politicians and bureaucrats.

The cure is also provided, however: the heroism of the individual; the old legend of the cowboy who rides into town and seeks justice.

Brody is clearly that figure here: an outsider in the corrupt town of Amity (he's from the NYPD); and the man who rides out onto the sea to face Amity's enemy head on, despite his own fear of the sea and "drowning."

Yes Brody was involved in the cover-up, but Americans don't like their heroes too neat. Brody must have a little blood on his hands so that his story of heroism is also one of redemption.

Why is Jaws so enduring and appealing?

Simple answer: it's positively archetypal in its presentation of both the monster -- a sea-going dragon ascribed supernatural power -- and it's hero: an every-man who challenges city hall and saves the townsfolk.

This hero is ably supported by energetic youth and up-to-date science (Hooper), and also wisdom and experience in the form of the veteran Quint.

.

You're Gonna Need A Bigger Boat

You can't truly engage in an adequate discussion of Jaws without some mention of film technique. The film's first scene exemplifies Spielberg's intelligent, visual approach to the thrilling material.

This introduction to the world of Jaws -- which features a teenager going out for a swim in the ocean and getting the surprise of her life -- proves pitch perfect both in orchestration and effect. Hyperbole aside, can you immediately think of a better (or more famous) horror movie prologue than the one featured here?

The film begins under the sea as Spielberg's camera adopts the P.O.V. of the shark itself. We cling to the bottom of the ocean, just skirting it as we move inland.

Then, we cut to the beach, and a long, lackadaisical establishing pan across a typical teenage party. Young people are smoking weed, drinking, canoodling...doing what young people do on summer nights, and Spielberg's choice of shot captures that vibe.

When one of the group -- the blond-haired seventies goddess named Chrissie -- gets up to leave the bunch, Spielberg cuts abruptly to a high angle (from a few feet away); a view that we understand signifies doom and danger, and which serves to distance us just a little from the individuals on-screen.

With a horny (but drunk...) companion in tow, Chrissie rapidly disrobes for a night-time dip in the sea, and Spielberg cuts to an angle far below her, from the bottom of the ocean looking up. We see Chrissie's beautiful nude form cutting the surface above, and the first thing you might think of is another monster movie, Jack Arnold's Creature From The Black Lagoon (1954).

Remember how the creature there spied lovely Julie Adams in the water...even stopping to dance with her (without her knowledge) in the murky lagoon?

Well, that was an image, perhaps, out of a more romantic age.

In this case, the swimmer is nude, not garbed, and contact with the monster is quick and fatal, not the beginning of any sort of "relationship."

In a horrifying close-shot, we see Chrissie break the surface, as something unseen but immensely powerful tugs at her from below. Once. Then again. After an instant, you realize the shark is actually eating her...ripping through her legs and torso. She begs God for help, but as you might expect in the secular 1970s there is no help for her.

The extremely unnerving aspect of Spielberg's execution is that recognition of the shark's attack dawns on the audience as the same time it dawns on Chrissie. She doesn't even realize a leg is gone at first. It's horrifying, but -- in the best tradition of the genre -- this scene is also oddly beautiful.

The gorgeous sea; the lovely human form. The night-time lighting.

Everything about this moment should be romantic and wonderful, but isn't.

Again, you can detect how Spielberg is taking the malaise days mood of the nation to generate his aura of terror; his overturning of the traditional order. Just as our belief in ourselves as a "good" and powerful nation was overturned by Vietnam and Watergate.

The more puritanical or conservative among us will also recognize this inaugural scene of Jaws as being an early corollary of the "vice precedes slice and dice" dynamic of many a slasher or Friday the 13th film. A young couple, eager to have pre-marital sex (after smoking weed, no less...) faces a surprise "monster" in a foreign realm.

That happens here not in the woods of Crystal Lake, but in a sea of secrets and monsters. It's also no coincidence, I believe, that the first victim in the film is a gorgeous, athletic blond with a perfect figure. Chrissie is the American Ideal of Beauty...torn asunder and devoured before the movie proper has even begun.

If that image doesn't unsettle you, nothing will.

I wrote in my book, Horror Films of the 1970s (McFarland; 2002), that, ultimately the characteristics that make a film great go far beyond any rudimentary combination of acting, photography, editing and music. It's a magic equation that some films get right and some don't. Jaws is a classic, I believe, because it educates the viewer about the central diabolical threat and then surprises the viewer by going a step further and hinting that the great white shark is no mere animal, but actually an ancient, malevolent force.

The film also brilliantly reflects the issues of the age in which it was created. And finally, Jaws updates the archetypes of good and evil that generations of Americans have grown up recounting, even though it does so with a distinctly disco decade twist. The Hooper-Brody-Quint troika is iconic too, and I love the male-bonding aspects of the film, with "modern" men like Brody and Hooper learning, eventually, to fall in love, after a fashion, with the impolitic Quint...warts and all.

Finally, you should never underestimate that Jaws depends on imagination and mystery.

It is set on the sea, a murky realm of the unknown where the shark boasts the home field advantage. Meanwhile, man is awkward and endangered there. We can't see the shark...but he can see us. With those black, devil eyes.

When you suddenly realize that the only thing standing between Brody and those black eyes is a thin layer of wood (the Orca); when you think about all the information we've been given about great whites and their deadly qualities, you'll agree reflexively -- instinctively -- with the good chief's prognosis.

We're gonna need a bigger boat.

June 1, 2025

50 Years Ago: Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze (1975)

Historically-speaking, the science fiction and fantasy cinema has battled high camp -- a form of art notable because of its exaggerated or over-the-top attributes -- for over six decades.

That long battle is definitively lost in Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze (1975), a tongue-in-cheek film adaptation of the pulp magazine hero (or superhero) created by Henry W. Ralston and story editor John L. Nanovi (with additional material from Lester Dent) in the 1930s.

The seventies movie, now 50 years old, rom producer George Pal (1908 – 1980) and director Michael Anderson brazenly makes a mockery of the titular hero’s world, his missions, and even his patriotic belief system. That the film is poorly paced, and looks more like a TV pilot rather than a full-fledged motion picture only adds to a laundry list of problems.

First some background on high camp: when camp is discussed as a mode of expression, what is really being debated is a sense of authorial or creative distance. When a film is overtly campy, the author or authors (since film is a collaborative art form…) have made the deliberate decision to stand back and observe the property being adapted from a dramatic and in fact, critical distance. They find the subject matter humorous, or worthy of ribbing, and have adapted by that belief as a guiding principle.

Notably not all creative “standing back” need result in a campy or tongue-in-cheek approach, and instead can help a film function admirably as pastiche or homage. In movies like Star Wars (1977), Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981 ) and even Scream (1996), there is a sense of knowing humor at work, but a campy tone is not the result.

In short, then, the camp approach represents sort of the furthest artistic distance a creator can imagine him or herself from his or her material. Worse, that great distance often seems to emerge from a place of genuine contempt; from a sense that the adapter is better than or superior to the material being adapted…and thus boasts the right/responsibility to mock said property.

Although Dino De Laurentiis’s King Kong (1976) and Flash Gordon (1980) are often offered up on a platter as Exhibits A and B for “campy” style big-budget science fiction or fantasy films, those examples don’t actually fit the bill very well.

Rather, close viewing suggests that Kong and Flash boast self-reflexive qualities and a sense of humor, but nonetheless boast a sense of closeness to the material at hand. In both films, in other words, the viewer gets close enough to feel invested in the characters and their stories, despite the interjection of humor, self-reflexive commentary or rampant post-modernism. When King Kong is gunned down by helicopters…the audience mourns. And when Flash’s theme song by Queen kicks in and he takes the fight to Ming the Merciless, we feel roused to cheer at his victory. We may laugh at jokes in the films, but we aren’t so far – distance-wise - that we can’t invest in the action

However, a true “camp” film negates such sense of meaning or identification, and instead portrays a world that is good only for a laugh, no matter the production values, no matter the efforts of the actors, director, or other talents.

Doc Savage: Man of Bronze is such a campy film, one that, post-Watergate, adopts a contemptuous approach to anyone in authority, and, in facts, makes heroism itself seem ridiculous and unbelievable. There are ample reasons for this approach, at this time in American history, but those reasons don’t mean that the approach is right for the Doc Savage character. After all, who can honestly invest in a hero who is so perfect, so square, so beautiful that the twinkle in his eye is literal…added as a special effect?

Although many critics also mistakenly term Superman: The Movie (1978) campy that film revolutionized superhero filmmaking because it took the hero’s world, his powers, and his relationships seriously. Certainly, there was goofy humor in the last third of the film, but that humor was never permitted to undercut the dignity of Superman, or minimize the threats that he faced, or to mock his heroic journey.

Again, Doc Savage represents the precise opposite approach. The film plays exceedingly like a two-hour put-down of superhero tropes and ideas, and wants its audience only to laugh at a character that actually proved highly influential in the World War II Era. The result is a film that might well be termed a disaster.

"Let us be considerate of our country, our fellow citizens and our associates in everything we say and do..."

International hero Doc Savage (Ron Ely) and his team of The Fabulous Five return to New York City only to face a deadly assassination attempt upon receiving the news of the death of Savage’s father.

After dispatching the assassin, Savage decides to fly to Hidalgo to investigate his father’s death. He and his Fabulous Five are soon involved in a race with the nefarious Captain Seas (Paul Wexler) to take possession of a secret South American valley, one where gold literally bubbles-up out of the ground…

"Have No Fear: Doc Savage is Here!"

With a little knowledge of history, one can certainly understand why Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze was created in full campy mode.

In 1975, the United States was reeling from the Watergate Scandal, the resignation of President Nixon, the Energy Crisis, and the ignominious end of American involvement in Vietnam. The Establishment had rather egregiously failed the country, one might argue, and so superheroes – scions of authority, essentially – were not to be taken seriously. You can see this quality of culture play out in the press’s treatment of President Gerald Ford. An accomplished athlete who carried his University of Michigan football team to national titles in 1932 and 1933, Ford was transformed, almost overnight, into a clumsy buffoon by the pop culture. It was easier to parse Ford by his pratfalls than by his prowess.

High camp had also begun to creep into the popular James Bond series as Roger Moore assumed the 007 role from Sean Connery, in efforts like Live and Let Die (1972) and The Man with the Golden Gun (1974). And on television, the most popular superhero program, TV’s Batman (1966 - 1968) had also operated in a campy mode

But, what films like Doc Savage fail to do, rather egregiously, is take a beloved character on his or her own terms, and present his hero to an audience by those terms. Instead of taking the effort to showcase and describe why Doc Savage’s world exists as it does in the pulps, the film wants only to showcase a world that easily mocked. The message that is transmitted, and which, generously, might be interpreted as unintentional is simply: this whole superhero world is silly, and if you like it, there’s something silly about you too.

In some sense, Doc Savage is a reminder of how good the British Pellucidar/Caprona movies of Kevin Connor are. Their special effects may be poor by today’s standard, but the movies take themselves and their world seriously. You can see that everyone involved is generally working to thrill the audience, not to prove to the audience how silly the movie’s concepts are.

Alas, camp worms its way into virtually every aspect of Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze . An early scene depicts Savage pulling an assassin’s bullet out of a hole in his apartment wall, and knowing instantly the caliber and the make of the weapon from which it was fired. In other words, he is so perfect (a scholar, philosopher, inventor, and surgeon…) that his skill looks effortless…and therefore funny.

Yet the pulp origins of the character make plain the fact that Doc Savage achieved his knowledge through hard work, and rigorous training. When you only see the end result in the movie, his intelligence and know-how is mocked and made a punch-line. The movie-makers didn’t need to do it this way. Savage could have undertaken an investigation, but it’s funnier just to make him all-knowing, to exaggerate his admirable qualities as a character.

Another example of how camp undercuts and mocks the heroes of the film occurs later in the action. Doc and his team of merry men (The Fabulous Five) are invited aboard the antagonist’s yacht for a dinner party. While the bad guy, Captain Seas, and his henchmen drink alcohol, Savage and his men drink only…milk. Again, this touch is so ludicrous when made manifest on screen that it only succeeds in stating, again, the essential “silliness” of the Doc Savage mythos. Worse, Batman had done this joke, and better, in its 1966 premiere. So the milk joke isn’t even original.

Perhaps the campies aspect of the film involves the atrocious soundtrack. The movie is scored to the work of John Phillip Sousa (1854 – 1932), the “American March King.” Rightly or wrongly, Sousa’s marches have become synonymous with Americana, Fourth of July parades and firework displays, with the very archetype of patriotism itself. To score Savage’s silly adventures to this kind of stereotypical “American” march is to say, essentially, that one is mocking that value.

I have nothing against mocking patriotism, if that’s your game. I can’t pass judgment on that or you. For me as a film critic, the question comes back to, again, the sense of distance created by the adapters, and whether that distance serves the interest of the character being adapted. In the case of Doc Savage, I would say that it rather definitively does not serve the character. The choice of soundtrack music essentially turns all action scenes -- no matter how brilliantly vetted in terms of stunts and visuals -- into nothing more than grotesque, unfunny parody.

Why do I feel that the character Savage is not well-served by this approach? Consider that all five of Savage’s “merry men” are important, philosophically not in terms of raw strength or athleticism, or even super powers.

Indeed, one is a legal genius, one is a chemist, one is a globe-hopping engineer, one is an archaeologist and one is an electrical wizard. Throw in Savage -- both a man of action and also a surgeon, for example – and consider the group’s original context: post-World War I.

These men survived the first technological war in human history, but a war – like all war – spawned by irrationality and passion. Their quality or importance as characters arises from the fact they are a modern, rational group of adventures, dependent on science, the law, medicine, and other intellectual ideas…not emotions or super abilities. In 1975, the world certainly could have used such an example; the idea that being a superhero meant rationality and intelligence. But the movie completely fails to deliver on the original meaning of the characters it depicts. Instead, Doc Savag e makes a mockery of these avatars of reason, and fails to note why, as a team, they represent something, anything of importance.

Some of the camp touches in Doc Savage are also downright baffling, rather than funny. One villain sleeps in what appears to be a giant cradle, and is rocked to sleep. The movie never establishes a reason -- even a camp one -- for this preference.

Although it is great to see Pamela Hensley -- Buck Rogers’ Princess Ardala -- in the film, I can think of almost no reason for anyone to re-visit Doc Savage. Who, precisely is this film made for? Fans of the pulps would be horrified at the tone of the material, and those who didn’t know the character before the film certainly would not come away from the film liking him.

In 1984, The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai successfully captured what was funny about characters like Doc, while at the same time functioning as an earnest adventure. Indeed, though I often complain about all the doom and gloom superhero movies of today, and what a boring drag they are, they are, as I have often written, a valid response to the era of Camp.

At either extreme -- camp or angst -- the superhero film formula proves tiring and unworkable, it often seems, and today....admit it, you're sick of it, aren't you?

May 24, 2025

40 Years Ago: A View to A Kill (1985)

Roger Moore’s final cinematic outing as James Bond, A View to a Kill (1985), is not generally considered one of the better titles in the 007 canon.

In fact, the critical consensus suggests precisely the opposite. Most aficionados consider the film to be Moore’s worst title, and place it in the (dreadful) company of Diamonds are Forever (1971), Sean Connery’s last canon film, and Die Another Die (2002), Pierce Brosnan’s final Bond film.

One reason that folks tend to dislike the film involves Moore himself. Even he acknowledged that, at 57 years old, he was likely too old to play 007. Moore's age is usually the elephant in the room when critics discuss this film, and yet there's a counterpoint worth making.

First, I hope I look as fit and handsome at the age of 57 as Moore does, in A View to A Kill . We should all be that fortunate. (I'm 55 years, so let's see how I'm doing in two!)

And secondly, I prefer Moore's Bond with a little age on him, when he's less the smirking pretty boy.

Yes, Moore is leathery and grizzled here, and yet, with age also comes experience. We look at Moore's deep-lined, but still-attractive visage here, and we can see life experience all over his face. His 007 has been to the rodeo before (six times, actually...), which is important to consider because experience is, perhaps, the one advantage Bond has in a battle against a brilliant sociopath: Max Zorin. Lest we forget, the posters for A View to a Kill asked, specifically: "Has James Bond finally met his match?"

If this tag-line is the movie's chosen thematic terrain, then the character of each combatant in this contest is significant, as I'll write about further. Moore's humanity (reflected in his graceful, but obvious aging) thus plays into the movie's central juxtaposition of genetic perfection/moral emptiness vs. humanity/morality.

Critics complain so much about Moore's age because -- let's face it -- it's an easy target. I remember back when Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986) was released, critics were calling the Enterprise crew "the over the hill gang." Well, what I wouldn't give, in 2025, to have four or five more Star Trek films, today, featuring that particular "over the hill" crew.

Broadly speaking, I would hope people could judge a work of art on more than just the superficial quality of age, and looks. But that hope is, frankly, in vain. Critics often go for the low-hanging fruit.

Despite the brickbats, I have -- since first seeing A View to a Kill in theaters in 1985 -- found myself frequently re-watching the film, as though checking in again to see if it remains such a poor effort. I always return thinking that there is something -- something -- there.

But on re-assessment, I absolutely see the same deficits.

And yet A View to a Kill still intrigues me. In fact, I would argue it is not nearly as bad as the other two 007 films that I name-checked above. Moore’s final outing carries such an endless fascination for me, I suppose, because it is all over the map. The tone is wildly inconsistent, for example. It is a film of notable highs, and dramatic lows.

Consider that A View to a Kill features -- courtesy of Duran Duran -- one of the most memorable title tracks in the whole franchise (right up there with Goldfinger [1964], Live and Let Die [1973], and Skyfall [2012).

Consider, also, the film’s (generally) superior casting. The film features Christopher Walken, Grace Jones, and Patrick Macnee. That’s an “A” list supporting cast.

In addition, the set pieces include amazing stunt-work and beautiful location photography, all scored to thrilling and lugubrious perfection by John Barry.

Still -- quite clearly – there’s something amiss with the film overall. Sir Roger Moore himself reported his dislike of A View to a Kill. It was his least favorite of all his 007 appearances. He found it too violent, too sadistic, and, as noted above, judged himself too old to play the part.

Drilling down further, I suspect that what fascinates me about the film is precisely what troubled Moore. The film is darker than most of the other Bond films from this era, and in that way, an absolutely appropriate lead-in to the reality-grounded Timothy Dalton era.

Yet for every foray into darkness and sadism, A View to A Kill hedges its bets with an unnecessary and silly joke, or action scene. The film keeps teetering towards an abyss of darkness, and then keeps backing away from it, into comic inanity.

Unlike Moore, I believe the film would have worked much more effectively if it maintained or sustained the dark atmosphere, and didn’t attempt to play so many moments lightly. A serious approach makes more sense, thematically, given the nature of the film’s villain: genetically engineered Max Zorin, and his plan for human carnage and cataclysm.

Lacking thematic and tonal consistency, A View to a Kill is a sometimes satisfying, sometimes inadequate Bond film, but ceaselessly fascinating. I understand why so many scholars and critics count it as Moore’s worst, while simultaneously feeling that there is also much to appreciate here.

Perhaps a better way of enunciating my point about the film is to say that I can view how the movie, with a few changes, could have been one of the strongest entries in this durable action series, especially as Bond prepared for a big transition to another actor, and to another style and epoch of action filmmaking.

“Intuitive improvisation is the secret of genius.”

In Siberia, James Bond, 007 (Roger Moore) follows up on the investigation of the deceased 003, tracking down a computer microchip, produced by Zorin Industries, that can withstand an electromagnetic pulse. The Soviets also want the chip recovered, and attempt to kill Bond before he makes a successful escape (in a submarine that looks like an ice berg).

Back in London, M (Robert Brown), assigns Bond to investigate Zorin (Christopher Walken), a former KGB agent, now entrepreneur.

Zorin’s interests are varied. Beyond his tech company (which produces microchips), he breeds and sells horses. At Ascot Racetrack, Bond, Moneypenny (Lois Maxwell), and M16 agent Sir Godfrey Tibbett (Patrick Macnee), observe Zorin’s newest colt, Pegasus, an animal that may be the result of genetic manipulation, like Zorin himself is rumored to be.

Bond then heads to Paris to meet an informant, Aubergine (Jean Rougerie), at the Eiffel Tower, who possesses information about an upcoming horse auction at Zorin’s extravagant French estate. The informant is killed by Zorin’s hench-person, the imposing May Day (Grace Jones), who flees Bond by parachuting from the Tower.

Bond pursues, and sees Zorin and May Day escaping together in a boat.

Bond then goes undercover, with Tibbett at his side, as a wealthy horse buyer, at Zorin’s event. There, he confirms that Pegasus is the product of genetic manipulation and steroid use. He also encounters a mystery woman, Stacey Sutton (Tanya Roberts), whom Zorin pays five million dollars.

The next phase of Bond’s investigation leads him to San Francisco, where Sutton lives, and where Zorin is planning Operation Main Strike, a man-made earthquake that will destroy Silicon Valley, and leave Zorin the sole world provider of computer micro-chips.

After Bond teams with Mayday to stop the earthquake, Zorin abducts Stacey, and flees the city by blimp. Bond pursues, and the nemeses fight to the death atop the Golden Gate Bridge.

“What’s there to say?”

A View to a Kill feels so schizophrenic because it vacillates between extreme seriousness or darkness, and then moments of ridiculous humor. Instead, the film should have stayed with the serious tone, which benefited Moore’s Bond immensely in my favorite from his era: For Your Eyes Only (1981).

Why should the jokey moments have been downplayed, or jettisoned, and the darker moments, highlighted?

For a few reasons. Consider, first the sweep or trajectory of film history. Overall, it might be viewed as a shift from the artificial and stagey, to the naturalistic and real, or gritty. Certainly, that is the direction the Bond films have headed in, moving to Dalton, and then, finally, to Craig. Modern audiences apparently seek more reality, and less theatricality and camp in their thrillers. A View to a Kill demonstrates the damaging juxtaposition of these two approaches, and should have settled on one.

I choose the darker, more serious approach for this film, because of the gravity of the conflict. Here, Bond challenges Zorin, a sociopath, and a person not bound by morals or laws. Zorin is also engineered (by his mentor and father-figure, a Nazi scientist named Dr. Mortner) to be physically strong, and, frankly, a (mad) genius.

Bond, by contrast, is the product of natural biology, and bound by laws and some code of ethics or morality. But 007 has his experience and training to benefit him, and make him a contender. This is a conflict of two very unlike men. In a way, the dynamic is not entirely unlike Khan vs. Kirk in Star Trek , except for the fact that Kirk is much more up-front about his deficits than Bond is.

Except for rare occasions such as Never Say Never Again (1983), the films do not acknowledge Bond’s aging. In the Roger Moore films, furthermore, audiences don’t really know Bond’s deficits as a human being. Instead, he’s a bit of a plastic-man in this incarnation, able to undertake any physical challenge with perfect acuity. Because Bond's aging is not acknowledged in A View to the Kill , the real nature of the conflict between Zorin and Bond is lost to a certain degree.

Moore’s age could have worked for the picture, instead of against it, had it been acknowledged with Moore's sense of humor, and again, his grace. Imagine an older, more world-weary, less physically “perfect” Bond being forced to confront a kind of superman with no sense of morality or humanity. It could have been his greatest test, and acknowledging Bond’s age would have created a greater contrast between the two characters and their respective traits.

Still, the grave or serious attitude in A View to a Kill is justified.

One can dislike the sadistic violence, of course, but the violence makes sense given this tale. Zorin possesses as little regard for underlings as he does for his enemies. People are just a means to an end to him. They may be loyal to him, but he doesn’t care.

His lack of caring, of empathy, is what gives him his power. Zorin can gun down his employees without caring, and then offhandedly quip that his operation is moving "right on schedule." He can kill a million people in Silicon Valley for his own ends, and not see how evil his plan is. He can achieve his ambitious ends because he possesses no sense of his limitations, and no sense that other people matter.

These qualities make Zorin different from the Bond villains of recent vintage, who were more grounded in reality. Kamal Khan ( Octopussy [1983]) was a glorified jewel thief who became enmeshed in the Cold War plot. In the end, he was still a jewel thief. And before him, Kristatos was, similarly, a grounded-in-reality “agent” for the Soviet Union, attempting to conduct an act of espionage (acquire the ATAC and return it to his KGB masters).

Zorin represents a dramatic return to the Drax/Stromberg school of villainy, but in far less cartoon-like terms. The camp elements of Drax and Stromberg’s stories are mostly absent here, at least in terms of Zorin’s world, and so he emerges as a dire, physical and mental threat to Bond’s success.

Christopher Walken brings his patented weirdness -- and brilliant unpredictability -- to the role, making Zorin a dramatic and legitimate danger to 007, and the world at large.

Significantly Drax and Stromberg were no physical match for Bond, and their megalomania had a kind of predictable movie villain logic to it. Zorin is determinedly different. Scene to scene, the audience is uncertain how Zorin will react, or respond to challenges. Walken brings the character to life in a dramatic way, and contrary to what some critics claimed, does not take the role lightly. Instead, Walken's Zorin is an almost perfect (crack'd) mirror, actually for 007. He is a fully developed individual with sense of humor and mastery over his world, but one who lacks morality, humanity, and empathy.

May Day fits in too with the idea of A View to a Kill as a grave, serious, violent film. She works for a sociopath, and is attracted to him; to his power and strength. But ultimately, May Day possesses something Zorin lacks: a conscience. How do we know? Because she makes emotional connections to people (like Jenny Flex), that Zorin can’t make, or can't even understand.

Unfortunately May Day’s conflict could also have been developed far more than it is. Her decision to fight Zorin plays more like a third-act gimmick than a credible character development, even if the seeds for that character development are right there, in the script, and on screen.

A View to a Kill should have been the supreme contrast between a man who kills for reasons of morality (Queen and Country, essentially) and a man who kills for no moral reason whatsoever. The other characters, like May Day, are the collateral damage in their contest.

Instead, however, the movie’s essential schizophrenia -- perhaps cowardice -- diminishes its effectiveness.

Let’s gaze for a moment at the (almost...) fantastic pre-title sequence in Siberia, which highlights some of the most amazing (and well-photographed) stunts of the entire Moore era…and that’s saying something, given the pre-title sequence of The Spy Who Loved Me, or the mountain climbing sequence in For Your Eyes Only.

Barry’s score here is moody and serious, the matters at hand are absolutely life and death, and then…in the middle of it, we get a dumb joke to break the mood: California Girls by the Beach Boys (but performed by cover band) gets played as Bond uses one ski (from a bob-sled) to surf a lake. The tension of the set-up -- so assiduously established -- is punctured, and we are asked, as we are asked frequently in Moore’s era, to laugh instead of legitimately invest in 007's world.

Again and again, the movie lunges for the cheap gag, rather than embracing the seriousness of the affair.

After Zorin has committed point-blank, brutal murder and devastating arson in San Francisco, and is about to detonate a bomb that will cause a massive earthquake and kill millions, we are treated to a joke action sequence with Bond and Sutton aboard a run-away fire engine.

The stunts are impressive, sure, but to no meaningful, thematic, or even tonal point. Do we really need to see a put-upon cop get his squad car pulped, while he reacts with angst? Do we really need the draw-bridge operator joke, as he shrinks back in his booth, recoiling from the demolition? Do we really need to see Bond swinging haplessly side-to-side, on an un-tethered fire engine ladder?

Only minutes after audiences gasp over Bond’s delicate rescue of Stacey from the roof of City Hall -- losing his footing and nearly falling from a tall ladder -- we’re suddenly in The Cannonball Run (1981), or some such thing.

As the movie leads into its amazing finale, a legitimately tense (and very realistic seeming and vertigo-inducing) fight atop the Golden Gate Bridge, we also have to get the requisite shot of Bond’s manhood in danger, as the blimp flies too near an offending antenna, and threatens his crotch.

I’ll be honest here: The Golden Gate Bridge set-piece is one of my all-time favorites in the Bond series.

The location shooting is amazing. The score is pulse-pounding, and the dizzying heights of the bridge rival For Your Eyes Only’s mountain-top finale. There’s a sense of chaos unloosed too, as Mortner arms himself with a grenade, it detonates, and the blimp shifts.

And then there’s the physical fight, at those vertiginous heights, between Zorin and Bond.

Zorin is armed with an axe. Bond has nothing to rely on but his wits. It’s a great, splendidly orchestrated sequence, and very few phony rear-projection shots take away from the stunt and location work. The fight's outcome is perfect too. Starting to slip from his perch, Zorin giggles a little, before plunging from the bridge to his death.

I love that little laugh, and Zorin’s brief moment of realization of defeat/irony, before he falls.

But before reaching that incredible conclusion, we have to deal with such absurdities as a large, loud blimp sneaking up on Stacey, a return visit to our put upon SF cop (now directing traffic), and Bond’s crotch in danger from that antenna.

These gags are not only dumb and unnecessary, they take away from the movie’s serious approach; an approach that could have led us smoothly into the Dalton era of a more realistic, graver 007 universe. We have seen so many fan edits of Star Trek or Star Wars movies in recent years. I’d love to see a fan edit of A View to a Kill in which some of the cringe-worthy gags got omitted, and the grave tone of the movie, instead, was maintained throughout.

Obviously, such an edit would not fix some things.

I would much have preferred to see a tired, bloodied Bond here, instead of one who can run at top speed, leap on draw bridges, or ski, and surf flawlessly through dangerous terrain. I would have rather seen a tired, huffing and puffing Bond face these challenges, using his wits. I feel like that my preferred approach to A View to a Kill would have made it easier to invest in the story, and been a real proper send-off for Moore’s Bond, whom I grew up with...and love without reservation.

Could the movie have -- with that approach -- gotten beyond Tanya Roberts’ grating performance as Sutton? Maybe. Maybe not.

Would the strangely brutal violence in Zorin's mine have felt more appropriate, or better justified? I suspect these deficits would have been judged differently, had a consistent tone been applied to A View to a Kill.

Again this film fascinates me almost endlessly. Sometimes -- such as in the Golden Gate climax -- it’s nearly a great James Bond movie. And some of the time a View to a Kill is a terrible Bond movie (the fire engine chase).

And the incredible thing is that from minute to minute, A View to a Kill vacillates between those two poles. There’s no middle ground. Diamonds are Forever is glib, glitzy, inconsequential and dumb throughout; Die Another Die , ridiculous and campy to its core.

But Moore’s final hour as James Bond is an animal all its own. A View to a Kill is a schizophrenic reach for greatness (and for the future direction of the Bond films…) that, simultaneously, plumbs the worst depths of the actor’s tenure in the role.

So, curse the bad, or appreciate the good?

I guess that's your view...to this film.

May 19, 2025

30 Years Ago: Die Hard with a Vengeance (1995)

The third Die Hard film re-establishes the action franchise’s reputation for excellence…with a vengeance.

The highest grossing American film of 1995, Die Hard with a Vengeance -- directed by John McTiernan -- thrives so fully as a work of art and a splendid entertainment because it lets go of many of the series’ past-their-prime characters, settings, and ideas.

Die Hard with a Vengeance is set during a hot, sweaty summer -- when temperatures rise -- instead of during a bitter cold Christmas, for example.

Similarly, this third Die Hard film doesn’t play the “fish out of water” card a third time, and the writers permit John McClane (Bruce Willis) to actually work in the city he actually calls home: New York. It’s nice to see him on his own turf for a change.

And even more rewardingly, this second sequel doesn’t shoehorn in cameos from supporting characters who are no longer crucial to the narrative.

Beloved but ancillary personalities such as Al Powell, Dick Thornburg and even Holly Gennero McClane are all absent from the action this time around, and that’s as it should be. Accordingly, they no longer divert time and energy away from the storytelling.

That probably sounds terribly harsh, but the fact of the matter is that action movies shouldn’t be forced to cater to the demands of fan service.They should focus, instead, on thrills, suspense and movement.

This Die Hard even eschews the franchise’s trademark obsession with a threat in a single, isolated location (a snowed-in airport, or burning building), for a sprawling city-wide chase instead.

Finally, Die Hard with a Vengeance adds an unforgettable new character to go toe-to-toe with McClane on his harrowing journey: Samuel L. Jackson’s Zeus Carver.

Accordingly, a man “alone” story (and franchise) becomes a buddy story instead; one with razor-sharp repartee and a high degree of consciousness about the black/wide divide in New York City at the time.

Where Die Hard 2: Die Harder (1990) enthusiastically regurgitated the ending from the first film, and took pains to repeat familiar scenes and character tropes, Die Hard with a Vengeance feels edgy and fresh by contrast. The franchise feels rejuvenated.

All these changes are a recipe for a return to form, and Die Hard with a Vengeance proves itself the second best film in the five-strong saga, behind only the original Die Hard.

“It’s nice to be needed.”

During a hot summer, a mad terrorist who calls himself Simon detonates a bomb in busy Manhattan. As the city attempts to respond to this act of terrorism, Simon demands that NY police officer John McClane -- now “two steps shy of being a full-blown alcoholic” -- play a game with him.

John, still mourning the end of his marriage, has no choice but to agree, and his first task involves wearing a sandwich-board with racial profanity printed on it in Harlem.

Understandably, John’s incendiary garb catches the attention of Zeus Carver (Samuel L. Jackson), a proud and outspoken individual who interferes…and thus becomes part of Simon’s plan.

Simon leads John and Zeus on a merry chase through the city, playing “Simon Says” with them regarding an incoming train, and a bomb in a park and other challenges.

Soon, John learns the truth: Simon is actually Peter Gruber (Jeremy Irons), the brother of Nakatomi terrorist Hans Gruber.

And while revenge appears to be his game, this Gruber shares his brother’s uncanny ability to misdirect authorities.

“This guy wants to pound you until you crumble.”

Die Hard with a Vengeance commences with a blast. The sequel opens with a crisply-cut montage of ordinary life in Manhattan, edited to the Lovin Spoonful’s 1966 hit, “Summer in the City.”

Then a bomb detonates on a busy street, flipping over cars in the process, and the idea of tempers flaring on this hot summer day is beautifully expressed.

This is a day which will see an explosion of violence and hot temperatures. Not only is this a summer-time setting a determined shift away from the wintry, Christmastime Die Hard and Die Harder , but the setting enhances the idea of temperatures rising among two very different men: John and Zeus. They are like oil and water, and do not work together easily or well.

And that idea, of course, ties in with the “binary liquid” bombs Simon utilizes. These explosives only detonate when two unlike fluids flood together into one vessel. On their own, they are not combustible, but in combination…watch out!

As one character notes “once the two liquids are mixed…be somewhere else.”

This is an observation abundantly true of John and Zeus as well. They bicker, quip, and challenge each other throughout the movie, with tempers soaring and accusations of racism flaring. But they also manage to solve problems, work together, and save the day.

When they combine, things do get hot, though. Indeed, everywhere John and Zeus go, they behind leave a trail of destruction and explosions. They are very much two unlike ingredients combining to explosive effect.

I appreciate that the movie makes race an issue, and doesn’t soft pedal its importance in the dialogue. So much of Die Hard 2: Die Harder felt rote, a by-the-numbers repetition of the ingredients that made Die Hard so great.

Yet there seems an ambitious attempt here to move back into a realm approximating our reality. John and Holly have broken up, and their rift isn’t easily repaired. John is an alcoholic, and has lost his sense of purpose. The reality of racism -- and racial mistrust -- fits into this leitmotif as well, and neither main character is ever treated as the bad guy. Instead, they circle each other warily, wondering if the other is a racist, or just very, very opinionated. Both men are heroes.

The late great Michael Kamen (1948-2003) contributes another pulse-pounding score for a Die Hard film here, and in this case, he weaves the popular Civil War song “When Johnny Comes Marching Home” (1863) into the proceedings many, many times. It works beautifully in the context I’ve described.

It’s an exaggeration to say that John and Zeus are fighting a civil war with one another, perhaps, but the movie does feature the idea that Simon is provoking a war of sorts in New York while he waltzes into the Federal Reserve Building to rob its gold. Gruber knowingly makes temperatures rise on a hot day, so no one will detect his true agenda. He sets the City against itself. He sets blacks against whites. He even sets parents against police (setting a bomb in a school), and he mixes those “binary liquid bombs” of McClane and Carter. That sounds very much like the definition of a civil war.

Irons also gives audiences the third Die Hard villain in a row to fake an American accent or dialect, and the idea has totally lost its impact by now, even if, overall Irons makes for a fiendishly effective villain. I must admit, I enjoy the film’s call-back to Hans Gruber (Alan Rickman), and love the idea of that mastermind boasting an equally diabolical brother. Simon/Peter has some interesting tics, or at least appears to, but like his brother, he is really all about the money.

Die Hard with a Vengeance also succeeds because the action alternates from frenetic kineticism to buttoned-down suspense so assuredly.

Sure, we get some amazingly choreographed moments like John’s impromptu taxi drive through Central Park, but then -- moments later -- we get this contained, intimate suspense scene involving the defusing of a bomb, or the playing of a Simon Says game.

The film is actually like a game of Simon Says in terms of its structure. It stops then starts, then stops again, until given license to cut loose. Every Die Hard movie needn’t work in this way, of course but this new paradigm makes the film feel fresh and unpredictable.

Die Hard with a Vengeance possesses so much energy and verve, so much heat, if you will, that one might conclude it is only “two steps shy of being a full-blown” masterpiece.

May 18, 2025

20 Years Later: Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith (2005)

Revenge of the Sith (2005) finds the Galactic Republic embroiled in a Civil War with Separatists. Indeed, "War" is the very first word that appears in the film, on that famous yellow crawl.

Chancellor Palpatine (in office long past his term...) has been captured by the Separatists, and after an incredible space battle, Jedi Knights Obi-Wan Kenobi (Ewan McGregor) and Anakin Skywalker (Hayden Christensen) board the craft of General Grievous and Count Dooku (Christopher Lee) to rescue him. During the mission, Anakin slips towards the Dark Side by letting his vengeance get the better of him with aan act of murder urged on by Palpatine.

Meanwhile, Padme Amidala (Natalie Portman) reveals that she is with child, and this revelation terrifies Anakin, for he has been experiencing terrible visions (like the one about his mother, in Attack of the Clones .)

He fears that Amidala will die in childbirth and feels impotent to prevent this grim fate. Angry and feeling powerless Anakin seeks out the tutelage of Palpatine (Ian McDiarmid), who tells him that there are ways to save Amidala, if only he explores the Dark Side of the Force.

Eventually, feeling he has no option, Anakin succumbs. He betrays the Jedi Order but in doing so, no longer remains the man that Amidala loved. On opposite sides of the war now, Obi Wan and Anakin duel, and Obi Wan wins, leaving a hobbled, burned Anakin to die on the side of a volcano on the planet Mustafar.

While the Galaxy slips into darkness and an Empire is born, Amidala dies of a broken heart after giving birth to the twins, Luke and Leia. Anakin survives, but is now more machine than man, locked into a mechanical suit -- a cage -- and re-named Darth Vader.

In 1755, Benjamin Franklin wrote "Those who would give up essential liberty to purchase a little temporary safety deserve neither liberty nor safety."

That is the essential idea at the heart of Revenge of the Sith, both in terms of the Republic, and on a more personal level, Anakin himself. And, in the tradition of all great art, this is a message that relates directly to the times we live in.

What has happened to the Republic? Well, to face a grave and gathering threat (the Separatist movement), the Senate voted for the creation of a "standing" clone army to fight evil renegade Count Dooku. In thousands of years (and presumably having vanquished many other threats), the Republic never required such an army, but rather was safeguarded by the noble protectors of peace, The Jedi Knight.

But now?

Fear-mongering often makes people make bad, rash decisions.

The first chip away at individual liberty in the Republic thus occurs when the Senate sacrifices the principles it has honored for so long, and puts a huge military force under the control of one man, the Chancellor.

Then, by appealing to the Senate's sense of patriotism, the Chancellor is given further "Emergency Powers." He remains in office well past his appointed term, and then -- claiming an assassination attempt -- alters the structure of the Republic in the name of security. Now, he tells the Senate to "thunderous applause," it shall be a strong and safe Empire...but committed to peace.

This is how -- as Amidala says -- democracies die. The scared masses practically beg a "strong man" to protect them.

And he does. As he says to Darth Vader: "Go bring peace to the Empire." Alas, it is the peace of subjugation; the peace of oppression.

There are a number of interesting factors about this set-up that relate directly to America in the last several years (the time the prequels were made and released).

The first thing to consider is this: we saw in Phantom Menace exactly how an Emperor began his ascent, chipping away at democracy a piece at a time. A Dark Lord and his allies, using the technicalities of the law removed the Supreme Chancellor (Valorum) from office, consequently gaining power for themselves.

They did so by claiming that the Senate's bureaucracy had swelled to unmanageable and non-functional levels -- an anti-government argument -- and that Valorum himself was a weak man beset by scandal. The antidote was a self-described "strong leader," someone who could rally the Senate and get it to work again, someone like, say Palpatine. In other words, a man was chosen to replace a flawed leader, a man who could restore "honor and dignity" to the Republic.

In real life, of course, George W. Bush ascended to the Presidency, after the scandal-plagued Clinton. And after the attacks of 9/11, cowed Americans willingly accepted a massive new surveillance state with the passage of the Patriot Act. And Bush had this to say to the World on November 6, 2001:"You are either with us or against us" in this war on terrorism.

In May 2005, George Lucas explicitly put the following words into Anakin Skywalker's mouth: "If you're not with me, you're my enemy."

And Obi-Wan's rebuttal? "Only a Sith deals in absolutes."

Clearly, George Luca crafted Revenge of the Sith as a direct rebuke to the path America took post-9/11. Those who whine and cry that there is no such political message here are advised, simply, to grow up. You don’t have to agree with the message. You don't have to like it. But to deny its presence here is infantile.

What is clever and artistic about Lucas’s metaphor is not merely that it is timely (and frightening), but that Lucas tells his story on two parallel tracks. First, in terms of sweeping galactic governments, and second in personal, individual terms. Anakin goes through the same journey personally that the Republic citizenry undergoes on a wide scale.

Consider that he too is "terrorized," or rather, the victim of a terrible attack. Not necessarily by the Separatists, but by the Sand People on Tatooine. They kill his Mother. That loss hurts him deeply, and he pursues (mindlessly) his revenge against the agents who hurt him.

But then Anakin begins experiencing visions that he will also lose his beloved wife. So, like the Republic itself, Anakin willingly exchanges freedom and liberty for safety and security. He surrenders his golden ideals and turns to the Dark Side because he fears more "attack;" he fears the loss of his family. He does not heed Yoda's warning that "fear of loss is a path to the dark side."

Thus Anakin is a follower. Might as well be a clone.

Anakin is prone to this weakness early -- as we can tell from his discussion on Naboo with Amidala in Attack of the Clones -- when he notes that a Dictatorship would make things easier, and thus prove preferable to democracy. Indeed it would be easier, which is why some Americans so gladly, to this day, accept the idea of a Unitary Executive.

But why would we give up our own freedom, and hand it to someone else?

Only fear can make us do something so stupid.

For all his skills as a pilot and a warrior, Anakin would rather follow than lead; rather cede individual power and freedom to a dictatorship than make the hard decisions that go hand-in-hand with a democracy.