John Kenneth Muir's Blog, page 8

March 26, 2025

Nimoy Day: Baffled! (1973)

Early this week, I celebrated William Shatner's birthday, and today I want to draw attention to some of his co-star, Leonard Nimoy's great work too. Of course, Shatner is still with us. We lost the amazing Mr. Nimoy a decade ago, and still feel that loss a decade later.

Like Sweet, Sweet Rachel before it, Baffled ! concerns a person from our Modern Age of Reason and Technology (The 20th and 21st century) who becomes unexpectedly engulfed in a psychic “mystery” and must solve a crime related to it. These films are as much detective stories (or film noirs, I suppose you could argue) as they are horror pictures. They involve murder, robbery, and other criminal activity.

And also like that earlier film, Baffled ! is a bit slow-paced and over-long. The pacing seems off at points, and some action beats don’t succeed, either because of inadequate staging (bad rear projection) or a lack of suspense.

Finally, Baffled! too was designed to be the pilot for an ongoing TV series. Sweet, Sweet Rachel went on to become The Sixth Sense (1972), a series that starred Garry Collins and lasted two seasons .

Baffled! never went on to series format, even though the movie boasts some promise

What, exactly is that promise?

It’s in the performances, specifically. Leonard Nimoy and Susan Hampshire star as the duo investigating the unusual supernatural events, and there’s some good, interesting chemistry between the performers. For those of you who are familiar with Nimoy primarily as the unemotional Spock on Star Trek (1966-1969), Baffled! is a remarkable counterpoint. He’s charming, laidback, and quite funny in the telefilm. Susan Hampshire, playing an occult expert, is surprisingly sweet and innocent in the role, which is an interesting twist too. Where Alex Dreier and Gary Collins both performed their “psychic” support roles with utter solemnity and seriousness, Hampshire plays it all sincerely, but gently.

In all, Baffled! is intriguing, but not great.

“Evil forces do exist. Always have…”

During a competitive car race at the Pennsylvania Run, ace driver Tom Kovack (Nimoy) runs off the road when he experiences a psychic vision of a woman in trouble, in a manor house in England. An expert in psychic phenomena and student of the occult, Michelle Brent (Hampshire) meets with him later, and suggests to him that his vision was true; that he possesses a “rare and mysterious insight.”

At first, Kovack dismisses this possibility out-of-hand, but soon experiences a second and a third vision. In one such vision, he falls from the manor house -- which Michelle has identified real place, Wyndham House in Devon -- into s turbulent ocean over the cliff-side. After the startling vision, Kovack discovers that he is actually soaked.

Realizing he needs help to understand better what is happening to him, Kovack teams up with Michelle, and they had to England together, to stay at Wyndham House and investigate. There is another guest staying there too, a famous movie star, Andrea Glenn (Vera Miles). She is waiting for her estranged husband, and has brought their twelve-year old daughter, Jennifer (Jewel Blanch) to the house as well.

After Jennifer receives a necklace with a wolf-head pendant from her mysterious, absent father, the girl seems to age dramatically in a day, acting like a fifteen-year old, surly teenager.

Mrs. Farraday (Rachel Roberts), who runs the house, however, starts to appear much younger.

Tom becomes convinced that Andrea was the woman in danger in his first vision, and that some dark force has taken control of her daughter, Jennifer, and is plotting against her.

Baffled! is one of those cases in which a movie’s set-up is more intriguing, finally, than the actual plot or resolution of the plot. After all is said and done, the psychic plot is just a gimmick and the real motive here is for someone to acquire Andrea Glenn’s fortune.

The best part of this telefilm is the first half-hour, wherein Tom Kovack experiences his first psychic visions, and encounters Michelle, who encourages him to pursue them. The writing is strong, the performances a good, and there’s even a bit of a cinematic feel to the production.

Once the film has settled down in the British manor house, by contrast, the movie loses some of its interest, and comes to a near stand-still in terms of pacing. Unlike Sweet, Sweet Rachel and its follow-up, The Sixth Sense, the visuals in Baffled! aren’t even particularly stylish. Stylish, colorful murder sequences enlivened both earlier productions, and yet are absent here.

The movie’s real virtue is, frankly, Leonard Nimoy, who is so un-Spock-like here it is astounding. Tom Kovack is a mellow seventies bachelor (and race car driver), trying to make time with the ladies and commenting ironically on everything that happens to him. I wouldn’t say that Nimoy is Shatner-esque in the film, but he seems is downright effusive compared to his buttoned down, controlled performances as the half-Vulcan.

The mystery itself is a bit odd, and uninspiring, and director Philip Leacock fails to wring substantial suspense from the action, even when Kovack and Michelle become trapped in the bottom of the elevator shaft in Wyndham House. The film’s ending -- and restoration of order -- can be seen coming a mile away, and reflects the laws of the occult established as far back as The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890).

Baffled! also ends with a plug for a series that would never come. After the mystery is solved at Wyndham House, Kovack and Michelle decide to go their separate ways. But then -- just as he is getting in his car – Tom conveniently experiences another vision that shows someone (strangers) in danger. He summons Michelle, she jumps into his car, and they’re off to solve another psychic case.So, they’re a team!

There’s a part of me that is sorry that Baffled didn’t make it to series so we could see that team solve more intriguing mysteries. I would have loved to see Nimoy and Hampshire work together again, and feel that if the episodes were an hour instead of 90 minute, there would be less chance for the tediousness that impacts some moments here.

Today, Baffled! is more of a curiosity than an artistically satisfying endeavor, and I can’t help but wonder how history would have been different if the concept had become a hit, and Nimoy became well-known not just for Star Trek , but for playing a groovy, 1970s psychic investigator.

March 23, 2025

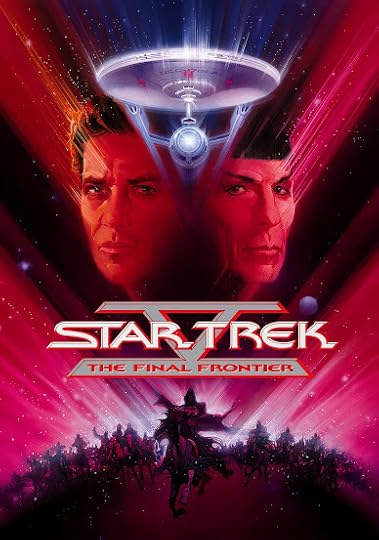

Shatner Day! Star Trek V: The Final Frontier (1989)

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier is widely-regarded as the worst Star Trek film ever made.

Of course, that's wrong.

These days we have Section 31 (2025) to take that title, but more importantly... Nemesis (2002)? Insurrection? (1998), Generations ? (1994)

I'd submit they are all worse than The Final Frontier.

Okay, okay, I am a Star Trek fan, and can see the silver-lining in every Star Trek movie.

So I am happy to enumerate the aspects I appreciate and admire about Star Trek V: The Final Frontier.

However, for the record, it is also necessary for me to note where and when things go dramatically wrong with the movie. So this review isn't going to be all "hugs and puppies."

That fact established there are indeed many components of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier worth lauding and I will explain in detail below why I feel that way.

Let's start, however, with a brief re-cap of the plot. The fifth Star Trek picks up with Captain Kirk (William Shatner) and his crew on vacation on Earth -- in the paradise-like setting of Yosemite -- when a dangerous hostage situation unfolds in the Neutral Zone.

There, on Nimbus III -- on the "planet of Galactic Peace" -- a Vulcan renegade named Sybok (Laurence Luckinbill) has taken hostage the Romulan, Klingon and Federation counsels. He has done so with an army of devout "believers." Sybok's gambit is to capture a starship so he can set a course for the center of the Galaxy and find the mythical planet Sha Ka Ree (named after Sean Connery), where he believes "God" awaits.

An unprepared U.S.S. Enterprise, with only a skeleton crew aboard, is assigned to rescue the hostages. The attempt fails, and Sybok commandeers the Enterprise using his particular brand of Vulcan brainwashing to persuade the crew to follow him. In particular, he frees each man he encounters of his "secret pain." Kirk soon learns that Sybok is Spock's (Leonard Nimoy) half-brother, a heretic who rejected Vulcan dogma and came to believe that emotion, not logic, is the key to enlightenment.

With a Klingon bird of prey in hot pursuit, the Enterprise passes through the Great Barrier at the center of the galaxy and encounters a mysterious planet. There, on the surface, awaits a creature who claims to be "God." Kirk questions the Being, and soon a vision of Heaven goes to Hell.

Because It's There: The Search for the Ultimate Knowledge; The Search for a Film's Noble Intentions

From Captain Kirk's effort to climb El Capitan at Yosemite National Park in the film's first scene to Sybok's probe through the foreboding and mysterious Great Barrier, Star Trek V: The Final Frontier concerns, in large part, a typically- Star Trek conceit: the human quest to reach a higher summit and to find at that apex a new or deeper truth about our existence.

When Mr. Spock asks Kirk why he would involve himself in an endeavor as dangerous as climbing a mountain, Kirk answers simply, "because it's there." That's an apt shorthand to describe one of our basic human drives. What our eyes detect, we want to explore, to experience. Enlightenment, for us, is often attained on the next plateau.

Sybok terms his search for "God" the search for the "ultimate knowledge" and he too seeks to climb a mountain after a fashion: penetrating the Great Barrier which protects a secret at the center of our galaxy. The means by which Sybok conducts his quest are not entirely kosher, however (kidnapping diplomats and hijacking a starship). But his quest, though coupled with his vanity, is sincere. An outcast among his Vulcan brethren, Sybok believes that if he can "locate" God, his beliefs will be validated, and thus perhaps re-examined by those who made him a pariah.

At one point late in the film, Kirk seems to suddenly realize that Sybok and he share a similar drive; that he has stubbornly refused Sybok the same liberty he affords himself, not merely to "go climb a rock," but to see, literally, what awaits at the mountain-top. Upon this realization, Kirk gazes knowingly at an old-fashioned captains' wheel in the Enterprise's observation deck. His hand brushes across a bronze plaque engraved with the legend "Where No Man Has Gone Before," a re-iteration of the franchise's "bold," trademark phrase. In a world where so many sci-fi movies depend on black-and-white portrayals of "good" and "evil," it's quite bold that The Final Frontier actually establishes a connection --- and one involving the meaning of life itself -- between protagonist and antagonist.

It should be noted here, perhaps, that Star Trek V: The Final Frontier is not out on some wacky limb, franchise-wise, in exploring the existence of "God," or a planet from which life sprang. On the former front, the Enterprise encountered the Greek God Apollo in the second-season episode "Who Mourns for Adonis" and on the latter front, discovered the planet "Eden" in the third season adventure "The Way to Eden." In a very real way, The Final Frontier feels like a development of this oft-seen Trek theme, as much as The Motion Picture was a development of themes featured in episodes such as "The Changeling" and "The Doomsday Machine."

What remains laudable about Star Trek V: The Final Frontier, however, is that screenwriter David Loughery, with director Shatner and producer Harve Bennett, carry their central metaphor -- discovery of the ultimate knowledge -- to the hearts of the beloved franchise characters. Star Trek V very much concerns not just the external quest for the divine, but a personal and human desire to understand the meaning of life.

Or, at the very least, the path to understanding the meaning of life.

What that desire comes down to here is one lengthy scene set in the Enterprise observation deck. There are no phasers, transporters, starships, Klingons, or special effects to be found. Instead, the scene involves Kirk, Spock, Bones and Sybok grappling with their personal beliefs, with their sense of personal identity and history, even. Sybok attempts to convert Spock and McCoy to his agenda by using his hypnotic powers of the mind. "Each man hides a secret pain. Share yours with me and gain strength from the sharing," he offers. One at a time, Kirk's allies crumble under the mesmeric influence. Then Sybok comes to Kirk, and the good captain steadfastly refuses Sybok's brand of personal enlightenment.

In refusing to share his pain, Kirk notes to Dr. McCoy (DeForest Kelley) that "you know that pain and guilt can't be taken away with a wave of a magic wand. They're the things we carry with us, the things that make us who we are. If we lose them, we lose ourselves. I don't want my pain taken away! I need my pain!"

This specific back-and-forth is the heart of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier. The Kirk/Sybok confrontation embodies the difference between Catholic Guilt (as represented by Kirk), and New Age "release" (as represented by Sybok). In terms of a short explanation, Catholic guilt is essentially a melancholy or world-weariness brought about by an examined life. It's the constant questioning and re-parsing of decisions and history (some call it Scrupulosity). And if you know Star Trek , you understand that this sense of melancholy is, for lack of a better word, very Kirk-ian.

As a starship captain, James Kirk has sent men and women to their deaths and made tough calls that changed the direction of the galaxy, literally. But he has never been one to do so blindly, or without consideration of the consequences. "My God, Bones, what have I done?" He asks after destroying the Enterprise in The Search for Spock , and that's just one, quick example of his reflective nature. In short, Kirk belabors his decisions, so much so that McCoy once had to tell him (in "Balance of Terror") not to obsess; not to "destroy the one called Kirk."

What Captain Kirk believes - and what is crucial to his success as a starship captain -- is that he must carry and remember the guilt associated with his tough decisions. He must re-hash those choices and constantly relive them, or else, during the next crisis, he will fail. His decisions are part of him; he is the cumulative result of those choices, and to lose them would be -- in his very words here -- "to lose himself." Pain, anguish, regret...these are all crucial elements of Kirk's being, and of the human equation.

By contrast, Sybok promises an escape from melancholy. His abilities permit him to "erase" the presence of pain all-together. This a kind of touchy-feely, New Age balm in which a person lets go of pain (via, for example, ACT: Active Release Technique) and then, once freed, suddenly sees the light.

Sybok's approach arises from the counter-culture movement of the 1960s (the era of the Original Series), and might be described -- albeit in glib fashion -- as "Do what feels right" (a turn-of-phrase Spock himself uses in the 2009 Star Trek ). But Sybok is a master of semantics. He doesn't "control minds," he says, he "frees" them. Left unexamined by Sybok is Kirk's interrogative: once freed from pain, what does a person have left? What remains when a person's core is removed? An empty vessel?

Isn't pain, borne by experience a part of our core psychological make-up? The New Age depiction of Sybok in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier led critic David Denby to term this entry "the most Californian" of the Star Trek films ( New York , June 19,1989, page 68).

In countenancing the false god of Sha Ka Ree, these belief systems collide. Sybok -- freed of pain and self-reflection -- is unaware of his own tragic flaws. Eventually he sees them, terming them "arrogance" and "vanity." But Kirk, who has always carried his choices with him, is able to face the malevolent alien with a sense of composure and entirely appropriate suspicion. Kirk is able, essentially, to ask "the Almighty for his I.D." because he has maintained his Catholic sense of guilt. He's been around the block too many times to be cowed by an alien who wants to appropriate his ship.

The lengthy scene in the observation deck, during which Sybok attempts to shatter the powerful triumvirate of Kirk, Spock and McCoy is probably the best in the film. Shatner shoots it well too, with Sybok intersecting the perimeters of this famous character "triangle" (of id, ego, and super-ego) and then, visually, scattering its points to the corners of the room when doubt is sewn.

And then, after Kirk's powerful argument and re-assertion of Catholic Guilt, the triangle (depicted visually, with the three characters as "points") is re-constructed. Sybok is both literally and symbolically forced out of their unified "space."

In point of fact, Shatner uses this triangular, three-person blocking pattern a lot in the film. Variety did not like the movie, but noted the power of this particular sequence in its original review: "Shatner, rises to the occasion," the magazine wrote, "in directing a dramatic sequence of the mystical Luckinbill teaching Nimoy and DeForest Kelley to re-experience their long-buried traumas. The re-creations of Spock's rejection by his father after his birth and Kelley's euthanasia of his own father are moving highlights."

While discussing Shatner, I should also add -- no doubt controversially -- that Shatner boasts a fine eye for visual composition. The opening scene on the cracked, arid plain of Nimbus III, and the follow-up scene set at Yosemite reveal that he has an eye not just for capturing natural beauty, but for utilizing the full breadth of the frame.

As a director, Shatner came out of television (helming episodes of T.J. Hooker ), but his visual approach doesn't suggest a TV mentality. On the contrary, I would argue that there are moments in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier that are the most inherently cinematic of the film series, after Wise's Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979) and Abrams' big-budget reboot of 2009.

What Does God Need With a Starship? Pinpointing the Divine inside The Human Heart and in the Natural World

I've noted above how Star Trek V: The Final Frontier involves the search for the ultimate knowledge, and uses two distinctive viewpoints (Catholic Guilt embodied by Kirk and New Age philosophy embodied by Sybok) to get at that knowledge.

What's important, after that "quest" is the film's conclusion about the specific "ultimate knowledge" gleaned from the journey.

In short order, in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier , the angry Old Testament-styled God-Alien reveals his true colors and demonstrates a capricious, violent-side. After Kirk asks "what does God need with a starship," "God" is wrathful and violent. And this is what the site Common Sense Atheism suggested was really being asked by our secular, humanist hero.

"One might ask, "What does God need with animal sacrifice? With a human sacrifice? With a catastrophic flood? With billions of galaxies and trillions of stars and millions of unstoppably destructive black holes? What does God need with congenital diseases and a planet made of shifting plates that cause earthquakes and tsunamis? Isn't the whole point of omnipotence that God could make a good world without all these needlessly silly or harmful phenomena?"

Moreover, why should humans obey the commands of someone as capricious, jealous, petty, and violent as the God of the Jewish scriptures?

This critical line of thought reminds me of my experience seeing Star Trek V: The Final Frontier in the theater with my girlfriend at the time, a devout Jew.

Afterwards, she was utterly convinced that Kirk and company had indeed encountered the Biblical, Old Testament God. And that they had, in fact, destroyed Him. Her reasoning for this belief was that "God" as depicted in the film actually looked and acted in the very fashion of the Old-Testament God.

On the former, front (God's appearance), The Journal of Religion and Film, in a piece "Any Gods Out There?" by John S. Schultes, opined: "This being appears in the stereotypical Westernized figure of the "Father God" as depicted in art. He has a giant head, disembodied, depicting an older man with a kind face, flowing white hair and booming voice."

On the latter front -- behavior -- there are also important commonalities. The Old Testament God was cruel, self-righteous, unjust, demanding, and acting according to a closely-held personal agenda (moving in a mysterious way?) without thought of courtesy or explanation to humans. Consider that the Old Testament God destroyed whole cities (like those of Sodom and Gomorrah), and that it's his plan to kill us by the billion-fold in the End Times, if we don't believe in him. The Old Testament God is indeed one of violence and punishment.

And this is precisely how Star Trek V: The Final Frontier depicts this creature. He wants to deliver his power -- his violence and judgment -- to "every corner of creation." Naturally, Kirk can't allow this brand of subjugation...even it comes from God.

Over the years, I have come to agree more and more with my former-girlfriend's assessment. The alien portrayed in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier may indeed be the Old Testament God of our legends. Just as Apollo was indeed, Apollo of Greek Myth in "Who Mourns for Adonis."

And, in fact, Captain Kirk kills God here. (Or rather, it's a cooperative venture with the Klingons...). In doing so, Kirk frees humanity (and the universe itself) from the oppression of superstition, judgment and tyranny. Ask yourself, keeping in mind Gene Roddenberry's visions of humanity and religion (expressed candidly in the TNG episode "Who Watches the Watchers"): is that Star Trek V’s ultimate message?

The ultimate knowledge, according to this Trek movie is that God only exists "right here; the human heart," as Kirk notes near the film's conclusion. Accordingly, The Journal of Religion and Society explains that this conclusion represents a narrative wrinkle true to "the collective history of Classic Star Trek," a re-assertion of Roddenberry-esque, secular principles. In his essay, "From Captain Stormfield to Captain Kirk, Two 20th Century Representations of Heaven, scholar Michel Clasquin concludes:

"In " Final Frontier ", Heaven turns out to be Hell: the optimism is deferred until the heroes have returned to the man-made heaven of the United Federation of Planets. The film ends where it began: with Spock, Kirk and McCoy on furlough in a thoroughly tamed Earth wilderness. This, the film tells us, is the true Heaven, the secular New Jerusalem that humans, Vulcans and a smattering of other species will build for themselves in the 24th century, a world in which the outward heavenly conditions reflect the true Heaven that resides in the human heart."

Clasquin's point here absolutely demands a re-evaluation of the book-end Yosemite camping scenes of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier. Many critics complained that the film takes a long time to get started, since the crew must "laboriously" be re-gathered from vacation.

However, if Star Trek V: The Final Frontier's point is that "God" resides in man's heart (and is, in fact, man himself) and that the Garden of Eden, or Heaven itself is "a tamed Earth wilderness," -- a finely-developed sense of responsible environmentalism, in fact -- then these two sequences of "nature" prove absolutely necessary in terms of the narrative. Heaven on Earth is within our grasp, the movie seems to note. We don't have to die to get there. We merely must act responsibly as stewards of our planet (or in Star Trek's universe, planets, plural). The human heart, and the Beautiful Earth: these are Star Trek V: The Final Frontier's (atheist) optimistic views of where, ultimately, Divinity resides. If you desire a Star Trek movie with some pretty deep philosophical underpinnings, look no further than William Shatner's The Final Frontier .

"All I Can Say is, They Don't Make 'Em Like They Used To: A Movie Shattered (not Shatnered...) by Poor Execution"

William Shatner handles many of the visual aspects of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier with flair and distinction. His impressive efforts are badly undercut, however, by three weaknesses. The first such weakness involves studio interference in the very story he wanted to tell. The second involves inferior special effects, and the third involves slipshod editing.

On the first front, William Shatner sought initially to make a serious, even bloody movie concerning fanatical religious cults and God imagery. His plan was shit-canned by Paramount Studios. Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986) had just proven a major success, and the Powers That Be judged this was so because the movie evidenced a terrific sense of humor, particularly fish-out-of-water humor. The edict came down that Star Trek V: The Final Frontier had to include the same level of humor.

Frankly, this edict was the kiss of death. The humor in Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home grew organically out of the situation: advanced people of the 23rd century being forced to deal with people and activities of the "primitive" year 1986. The scenario there called for fish-out-of-water humor, and no characters were sacrificed on the altar of laughs.

Above, I described the thematic principles of Star Trek V : seeking the ultimate summit both externally and internally, and discovering that the Divine is inside us -- or is, actually, the Human Heart. So how exactly, does Scotty knocking himself out on a ceiling beam, or Uhura performing a fan dance, or Chekov rehashing his "wessel" shtick fit that conceit?

The short answer is that it doesn't. Such humor had to be grafted on here, and it shows. It's forced, awkward, and entirely unnecessary. The inclusion of so much humor actually runs counter to the grandeur and seriousness of the story Shatner hoped to tell.

And then -- in a typical bout of bean-counter nonsense -- what does Paramount do next?

Well, it advertises and markets Star Trek V: The Final Frontier with the ad-line "why are they putting seat belts in theaters this summer?" suggesting that the movie is an action-packed roller-coaster ride! This is after they demanded the movie be a comedy!

Talk about assuring audience dissatisfaction. Tell audiences that the movie they are about to see is super-exciting and action-packed, and then give them Vulcan nerve-pinches on horses, Uhura and Scotty flirting with each other, and crewmen singing "Row, Row, Row Your Boat." Quite simply, The Final Frontier's marketing campaign didn't do a good job of managing audience expectations.

The second aspect of Star Trek V: The Final Frontier that damages it so egregiously involves the special visual effects. A movie like this -- about the search for God, no less -- must feature absolutely inspiring and immaculate, awesome visuals. We must believe in the universe that includes Sha Ka Ree, and the God Creature.

Originally, Shatner envisioned Sha Ka Ree turning into a kind of Bosch-ean Hell, featuring demons and rivers of fire. But what we get instead is a glowing Santa Claus-head in a beam of light, and...a much too familiar desert planet.

What's worse is that many visuals don't match-up. When Kirk's shuttle flies over the God planet initially, the surface of the world looks like a microscopic landscape (a sort of God's Eye view of the head-of-a-pin, as it were). But when the shuttle lands the planet just looks like a terrestrial desert. This is Heaven?

Perhaps Star Trek V could have surmounted this problem, since the TV series was never about special effects anyway, but about ideas. But the special effects in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier fail to even adequately render believable and "real" such commonplace Star Trek things as starships in motion or photon torpedo blasts. Watching Star Trek V: The Final Frontier is a little bit like watching Golan and Globus's Superman IV: The Quest for Peace (1986): the cheapness of the effects make you wince, and stands in stark contrast to a franchise's glory days.

And the editing!

Oh my, to quote Mr. Sulu.

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier is edited -- in polite terms -- in disastrous fashion. During Kirk, Spock and McCoy's escape on rocket boots through an Enterprise turbo shaft, the same deck numbers repeat, in plain view.

When Kirk falls from his perch high on El Capitan the movie cuts to a lengthy shot of Shatner -- in front of a phony rear-projection background -- flapping his arms.

And just take a look at how Kirk's weight, make-up, hair-cut, and disposition shift back-and-forth in his final scene with General Koord and General Klaa aboard the Klingon Bird of Prey. This mismatch was due to post-production re-shoots when the original ending was deemed unacceptable.

Forget the script (which might have worked without the studio-demanded humor). Forget the acting (which is pure Star Trek -- and, in my estimation, perfect for a futuristic passion play), it's the editing that scuttles this film.

Whether it's allowing us the time to notice that Sybok's haircut and outfit change on Sha Ka Ree, or permitting us to linger too long on visible wires in two fight scenes, Star Trek V's cutting is just not up to par.

Shatner should get to do a director's cut, and trim his misbegotten film down to a mean, lean eighty-five minutes. The worst editing, effects, and jokey moments would be excised, and audiences would be surprised, perhaps, how visually adroit, how dynamic, how meaningful and even spiritual this Final Frontier could be sans the theatrical release's considerable problems.

Let's face it, modern criticism often thrives on hyperbole, so it's fun and dramatic to declare that Star Trek V: The Final Frontier is one of the ten worst science fiction films EVER! The only problem is, it's not true.

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier conforms to Muir's Snowball Rule of Movie Viewing. Allow me to explain. Because Star Trek V: The Final Frontier is perceived by the majority of critics and Star Trek fans as "bad," everything about the film gets criticized, when -- in point of fact -- many other Star Trek movies feature many of the same goofy errors.

For instance, I have read some Star Trek fans complain vociferously about the fact that the Enterprise travels to the center of the galaxy here in a matter of hours. The fact that in First Contact, the Enterprise gets from the Romulan Neutral Zone to Earth in time to join a battle against the Borg, already in progress, goes unnoticed or at least uncommented upon. So, the starship got there in like, you know, a few minutes, I guess. But because First Contact is beloved and generally evaluated as good, it generally doesn't garner the same level of negative attention or scrutiny. When it fails in a spot here or there, it gets a pass.

Whereas, by contrast, the details in Star Trek V: The Final Frontier definitely draw heavier scrutiny. The "bad movie" snowball, once rolling down a hill, just grows larger and larger. We forgive less and less. Every aspect of the film is nitpicked and called into question, deservedly or not.

It becomes harder, then, to register and recognize the good.

Star Trek V: The Final Frontier is an ambitious failure. But ambitious may be the operative word here. The movie certainly aimed high, and hoped to chart some fascinating spiritual and philosophical ground that feels abundantly true to the Star Trek line and heritage.

But plainly, the execution leaves a lot to be desired.

Again, I renew my call for a Shatner-guided 85 minute version. One closer to his original vision, with improved special effects, and better editing. A new official release, re-modulated as I suggest, may be the only way for opinion-hardened Star Trek fans to see the good points of this admittedly problematic entry in the film canon.

March 22, 2025

Shatner Day: The Horror at 37,000 Feet (1973)

This TV movie, The Horror at 37,000 Feet -- from 1973 -- has not, historically, received a lot of love from critics or audiences.

It stars William Shatner as an alcoholic ex-priest, and even Shatner’s die-hard fans, believe that the movie is the worst production the icon has ever been associated with.

Well, I’m going to buck conventional wisdom a bit and give the telefilm a little much-needed love today. And, of course, Shatner is great, as always, in this film.

Although it is undeniably a cheap-jack production -- with virtually no resources upon which to draw -- The Horror at 37,000 Feet does succeed in effectively generating a sense of terror.

And it does so the old fashioned way.

Largely by hiding the titular horror from our eyes, and letting, instead, film grammar “sell” the scares.

First, a confession: I first saw this made-for-TV movie as a child, and it terrified me.

I have recalled, for probably three decades, isolated moments or images from The Horror at 37,000 Feet, such as a gaudily made-up baby doll “oozing” green death, or an unlucky passenger ejected from a plane in flight into the infinite sky at dawn.

I suspect that these images resonate, in part because director, David Lowell Rich, realized he had very few options. He had to marshal all the (meager) resources he had to create images that carried frightful impact.

There was no budget, apparently, to showcase bells and whistles. The was no budget to reveal the face of evil, to orchestrate elaborate special effects, or even afford the audience a single, solitary gaze at the “haunted” Druid altar that informs the film’s supernatural scares.

So Rich, instead, figured out, in many instances, how he could heighten suspense or anxiety utilizing visual compositions. I’ll write about a few of those in this review. But long story short: he picks the right tools for the right job. He finds the best angles to utilize -- at key moments -- to ramp up feelings of discomfort and ambiguity.

Essentially, his approach of necessity -- not to really show anything – echoes the movie’s narrative, which concerns a plane flight wherein something dark and malevolent mysteriously suspends the laws of physics.

It’s not clear what that force is -- Satan, Druids, or H.P. Lovecraft’s Old Ones -- but for one night, the summer solstice, this unseen power exerts control over one tiny corner of the human world.

Sure, the actors are mostly 1970s TV has-beens (Buddy Ebsen, Chuck Connors, Russell Johnson) and the writing is muddled at times.

But consider that the scariest movies aren’t always the ones that make the most rational sense, or which present the clearest explanations of things.

Sometimes the best ones are those in which “sense,” as we understand it, is almost graspable, and then, suddenly lost. We are scared by uncertainty, after all, not certainty.

Whether intentional or not, this kind of irrationality also echoes the dream language of nightmares.

The Horror at 37,000 Feet is a modest but effective little nightmare, for certain.

“The air feels funny tonight.”

AOA Flight 19X leaves Heathrow Airport by darkest night, bound for Long Island, New York. It is a cargo flight with only a few passengers aboard.

Among those passengers: a defrocked priest, Paul Kovalik (Shatner), a cranky business-man, Farley (Ebsen), a British physician, Dr. Enkalia (Paul Winfield), a model (France Nuyen), and an architect, O’Neill (Roy Thinnes) and his wife, Sheila (Jane Merrow)

The cargo in the hold belongs to O’Neill. He is transporting in a large crate the stones of an ancient altar found in an English abbey, from his wife’s land. The O’Neills' decision to remove the ancient stones from their native soil is a source of controversy, especially for another passenger, Mrs. Pinder (Tammy Grimes).

Once in flight, strange things begin to occur.

The pilot (Connors) and flight crew are shocked when the plane appears to be suspended in air, using fuel, but not moving. At first the crew suspects a dangerous, powerful head-wind. But even upon turning around, the plane can make no progress through the skies.

Then Mrs. O’Neill faints, and after awakening, speaks words in Latin. Paul identifies them as words used in a Satanic black mass.

The force in the cargo hold soon breaks loose, trapping an attendant on an elevator, and freezing Mrs. Pinder’s dog, Damon, solid. It then kills a flight engineer (Johnson).

Soon, strange green ectoplasm begins appearing all over the plane in flight, and the passengers panic.

They believe that they must sacrifice a passenger, preferably Mrs. O’Neill, to the dark forces manifesting on the jet.

But Kovalik -- who has lost his faith -- chooses to confront the terror for one just one glimpse of the supernatural world.

“We’re caught in a wind like there never was.”

I could easily make the case, as many other reviewers have done, that The Horror at 37,000 Feet is a bad movie.’:

That argument would look like this:

First, the movie is unoriginal in setting and conflict. At heart, it’s just another a 1970s Airport movie, about a plane in flight experiencing some form of existential jeopardy.

Been there, done that.

I could even go outside the “plane-in-flight” genre and note that as a horror production, this telefilm has superior antecedents. “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet,” a classic episode of The Twilight Zone (1959-1964) certainly generated scares aplenty, and it also featured William Shatner in a starring role.

So I could argue, without much effort that The Horror at 37,000 Feet is overly familiar, a retread.

I might also note the film’s inherent cheapness. As I noted in my introduction to this review, we never even see the altar that is the cause of the terror. It is crated up. Hidden from the eye. After a few scenes set an airport, we're on the plane for the whole movie. On the upside, this does generate a feeling of claustrophobia, at least.

And yes, the teleplay mixes up Devil Worship, Paganism and H.P. Lovecraft willy-nilly. All those aspects of the apparent “occult” are thrown into a cocktail blender and mixed, none-too-elegantly.

Then, finally, you have the actors chewing the (very limited) scenery, and a total lack of visual effects to back up the horror.

As Mystery Science Theater 3000 (1989-1999) once noted (of a different production) “Bad movie? You’re soaking in it.”

But let’s travel beyond surface values for a moment and dig a little deeper.

What The Horror at 37,000 Feet truly concerns is an outbreak of the irrational and supernatural in a world explicitly of the modern, the technological, the reasonable. Something older than Christianity itself awakens and seizes control of state-of-the-art human technology, a plane in flight.

Just the sight of this thing can kill you. It can freeze your blood.

And the old, irrational force, cannot be reckoned with using science, engineering, or any “daylight” recourse.

The flight team attempts maneuvers to escape the strange, inexplicable jetstream…all of which are (impossibly) ineffective. The interior of the plane freezes, even though the jet’s skin or hull has not been breached. And all over the plane, outbreaks of ectoplasm -- green goo -- sprout up.

In total, the forces of the irrational and nightmarish are infecting the plane, coming into the sunshine world of reality. It's a highly localized invasion, of a sort.

What does the Dark Force want? The passengers become a mob and settle on human sacrifice as the best answer. What do they sacrifice? Well, Mr. Farley burns all of his money. The wealthy businessman who has spent his life negotiating profitable deals immediately forsakes his God (capitalism) to save his life. How quickly he gives up a lifetime of greed and avarice in the face of something he can’t rationally grapple with.

But it is Paul’s journey which I find the most fascinating. He has given up his life as a priest because he never saw one iota of the Divine. All he wanted was one second of validation for his belief system that God exists. He never got it. And he turned to the bottle for comfort and succor.

Finally, Paul gets the opportunity to confront something beyond the concrete, beyond the rational. He dies for one peek at the “world beyond” ours. What he sees is terrifying, but also, ironically, a confirmation of the life he abandoned.

As Dr. Enkalia notes, “If there are Devils, there must also be Gods.”

I’ve written before about the Zeitgeist of the late 1960s and early 1970s, leading up to the premiere of Star Wars (1977). It was an era of intense cynicism and doubt in America, and in the pop culture. We lost a war, we had a president resign in disgrace, and one of our most popular weekly periodicals asked the question, on its cover, no less: “Is God Dead?”

We all seemed to be brooding in a state of existential angst and uncertainty.

The horror genre responded in full force to this period of questioning, and from 1967 – 1976 we saw a slew of films raising our doubts: Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Exorcist (1973), The Omen (1976), and beyond.

The Horror at 37,000 Feet is preoccupied with the same questions. It is of a piece with that historical and entertainment context. As it acknowledges with its settings, we’ve created a world of amazing technology and innovation. But are we spiritual beings?

And is there a spiritual order to the universe beyond the gadgets and forces we harness through science?

With no real budget to speak of, and no special effects, either, The Horror at 37,000 Feet visualizes an incursion of the supernatural realm into the realm of “reality.” The director deploys some terrific shots to do so.

Consider the moment, for example, wherein a flight attendant becomes trapped in a rapidly freezing elevator. The window is a narrow, vertical rectangle. But the director doesn’t limit our view to the glass. Instead, he shows us the whole door, so that as the flight attendant screams for help, her visual space in the frame is constricted by a considerable amount. She is inside a box within a box, to put it another way, trapped.

In a way, that’s a metaphor for all the passengers. They are trapped on a plane, a box of another sort, with no possibility of escape. Science has put them there (at 37,000 Feet), but the unknown is holding them there.

Secondly, as I’ve noted above, the film is about Paul’s desire and attempt to see the forces beyond human understanding. As The Horror at 37,000 Feet nears its conclusion, the perspective switches --for the only time in the movie, if memory serves -- to a P.O.V. shot.

Clutching a torch, and moving to the darkened back of the cabin (and the source of the terror), Paul approaches his moment of discovery.

It quickly becomes -- through the subjective camera angle -- our moment of discovery too. We see a fleeting glimpse of a person shrouded in a cloak.

And then we get the pay-off. An extreme close-up of Paul’s face as he sees his “proof” of the other world. It is a moment not of transcendence, but utter, soul-shredding terror. I know that many film lovers and critics love to dismiss Shatner as hammy or over-the-top in his acting choices. But it is his reaction shot, lensed in that extreme close-up that serves as the punctuation for the whole movie.

Paul gets his wish to see the other “reality,” and what he sees is so terrible that he cannot reckon with it.

I would say Shatner pulls this moment off with great success.

When Paul is ejected from the plane, however, terror gives way to something else. We see him in the sky, at dawn. The sun is emerging.

He will die, of course, and yet the order of the universe (the sun rising and setting) is restored. Paul paid for his glimpse of the “the Old Ones” with his life, but the next shot suggests the restoration of order, and perhaps, then, even the journey to Heaven.

Another sequence in the film is also well-shot. Late in the story, the passengers decide to attempt to trick the Old Ones. They use a child’s baby doll as a sacrifice. They cut Sheila’s hair and fingernails, and put it on the hunk of plastic.

Then, they give the doll to the dark force.

This sinister power sees through the trick, instantly, and green, bilious ectoplasm pours forth from the toy.

This is a creepy moment that requires virtually nothing in terms of expense. It is dream horror at its finest, bringing the doll to life, in a sense, as the lifeblood of The Other Side boils up within it.

I don’t argue that Horror at 37,000 Feet is a great production, or one of the all-time great horror films, only that it has something that makes it effectively unsettling.

That something, as I've hopefully pinpointed, is likely a grounding in the language of film grammar. The shots, in some weird way, enhance the irrationality of the teleplay, and therefore bring forward the idea of an irrational horror, and a time and place where -- for a horrifying 71 minutes -- two worlds seem to collide.

I find that many 1970s TV films manage to be extremely frightening, even today. This isn’t merely because my generation experienced them in childhood. It’s because they were made in a time when American society was questioning the pillars of our nation (faith, and patriotism), and because they were cheap as Hell.

If they were to work at all, the talents making telefilms such as The Horror at 37,000 Feet had to find (cheap) ways to showcase the horror in unusual but effective ways.

On those grounds, The Horror at 37,000 Feet may be silly and muddled and hammy, but it sure as Hell sticks the landing.

Shatner Day: The People (1972)

A young elementary school teacher, Melodye Amerson (Kim Darby) travels to a small, isolated farming community in the southwest to run the one-room school-house there. She has left behind a boyfriend, who worried that she would be alone in the middle of nowhere. Melodye’s response is that, in this new location, she’ll have “more time” to figure herself out.

On her arrival in the rural community of Bento, however, Melodye finds the young students distant, unemotional, and strange. Worse they are not allowed to sing, dance, make pretend, or otherwise express aspects of their imagination. The whole community seems shut down emotionally. The nominal leader of the town, Sol (Dan O’Herlihy) seems very reserved, and stern.

Also baffled by the incredibly healthy people of the town is Dr. Curtis (William Shatner), who wishes to study their hearty nature, and local medicines.

As Melodye and Dr. Curtis soon learn, the people of the town of Bendo are not and never can “be normal.” They are actually refugees from another, long-destroyed world. They emigrated to Earth, hoping to find safe harbor, but their ship blew up in the atmosphere on approach. Now, their people have settlements all over the world, mostly far from large human populations.

As Melodye soon learns from a student named Francher, these gentle, unassuming aliens possess advanced mental abilities, including ESP, and telekinesis. Melodye -- a bit of an outsider herself -- decides to stay on as the school teacher, and learn about the unusual community.

Executive-produced by Francis Ford Coppola, The People aired on The ABC Movie of the Week , on January 22, 1972. The telefilm is based on the novellas and short stories of much-beloved author Zenna Henderson (1917-1983), who wrote several tales involving “the People,” with titles such as “Ararat” and “Pottage.” The People is a loose adaptation of the latter tale.

Like many of its 1970’s brethren ( Night Slaves, The UFO Incident, or The Stranger Within ), The People involves aliens on Earth, but here the story is not -- at least for the most part -- horror-based.

On the contrary, The People is a straight-forward (and sympathetic) allegory for the immigrant experience in modern America. Specifically, these aliens of Bento -- because of their cultural differences -- choose not to assimilate or accommodate to the dominant culture of the local population. Instead, they “separate” (think: the Amish), setting up an isolated community and only tangentially relating to locals, like school teacher Melodye, or the physician, Dr. Curtis. The aliens separate from the human community not only to maintain their individual culture and beliefs, but to maintain their safety and security. They are afraid of being discovered, and exterminated, when their alien nature is discovered. But they are a danger to none, not knowing aggression or other violent impulses.

The situation of the aliens in Bendo is, impressively, mirrored by Melodye’s situation. If the “people” are outsiders to the human race, Melodye is an outsider to Bendo, and the alien ways she soon discovers there. The path she chooses, as an émigré, however, is accommodation. She doesn’t assimilate to the alien ways, leaving all her learning and rituals behind. Nor does she put a wall of separation around herself, so as not to be “contaminated” by ways not her own.

Instead, she attempts to share her beliefs (through teaching lessons at school) with the people, while she opens herself up to learning of their ways, as well. Dr. Curtis, played by a low-key William Shatner, selects much the same path. They are only humans in the town of aliens, and yet --for their own reasons -- they choose to make Bendo their home. As Curtis notes, he has “learned to respect the people and their customs.”

The People’s most compelling scene involves Melodye’s school project for the children, called “I Remember the Home.” Here, she asks each young student to draw what they remember of the place they hailed from. As she learns from the results of the lesson, “The Home” is another world all-together. But The People proves most artistically-adept as the story of the aliens is visualized through a series of children’s drawings, paintings, and sketches. The whole journey, from the old world, to the new one, is transmitted via art, and this is a great, symbolic way to fill in back story, or provide exposition.

Some of the levitation effects don’t look great today, and yet the special effects hardly matter. The unique thing about The People is that it concerns advanced, thoughtful people who have, at least largely, come to shun technology.

The film’s conclusion, with the aliens putting down “fear” to learn about the humans, is a hopeful one, too.

The story of diverse people learning to get along with one another is just as timely today, in 2017, as it was in 1972. As Melodye points out “different people are what make the world interesting.” How boring it would be if we were all the same, all living exactly the same way. The film’s conclusion is that the alien people possess a “wisdom and experience beyond anything we can imagine,” and that Earth “can be a place of love, as well as fear.”

But I like that this is not a one way street. The process of “separation” has not served all the people of Bento well, resulting in the need for contact, with those like Melodye, or Dr. Curtis. It is the immigrants, too, who learn to put down fear, not just the humans who encounter super-powered aliens.

The People was a back-door pilot for a series that never came, and which would have reunited the stars here, including Darby and Shatner (who first appeared together in the Star Trek episode “Miri,” in 1966). It’s a great shame that the series never came to be, as this TV movie is charming, sweet, and engaging

Although the central roles would need to be recast, it is not difficult seeing how this concept could be made to work again, in our modern environment, as an antidote to the rabidly anti-immigrant national dialogue of the past few years.

Not everyone who is different, or who carries different beliefs, is a monster. The People transmits that idea beautifully, although, honestly, I could do without the scene involving the flying kazoos.

Shatner Day: Mission Impossible "Encore"

"Encore" is one of the most audacious installments of the entire seven season run of Mission:Impossible (1966-1973). At times, the premise of this sixth season episode beggars beliefs, but at other times, the execution is so convincing that the audience buys the whole thing.

In "Encore," William Shatner guest stars as a gangster named Kroll who, nearly forty years earlier, committed the murder of a rival mobster, Danny Ryan. Kroll hid the body, and weapon used to kill him, but nobody knows where.

Accordingly, to this day, no one has been able to pin the murder on the powerful Kroll, or his partner, Stevens. Worse, to maintain their "innocence," Kroll and Stevens have been murdering all the witnesses to the crimes, arranging accidents for them. Their latest victim is a little old lady in a hospital. Kroll and Stevens blow up her room in the hospital to keep her from talking.

Enter the IMF.

Jim Phelps (Peter Graves) hatches a plan to turn back the clock. Using a potent combination of make-up, medicine, and a studio lot, the IMF endeavors to make Kroll believe it is 1937 again, and have Kroll relive the crime -- the murder of Ryan -- that they wish to solve, and nab him for. They hope, in the exact recreation on the lot of his home in Long Island, Kroll will make sure history happens twice, and show them where he intends to hide Ryan's body, and the gun,

In previous (and later) episodes of this stellar series, the IMF has tricked "marks" into believing they have been in comas, encountered ghosts, been cured of diseases, stranded on a desert island and other wild outcomes, in order to glean important information from them. In "Encore," however, the IMF must perfectly recreate an era half-a-century gone. If one detail is wrong, the plan fails. If one example of modernity is seen, the mission fails. If Kroll makes it off the studio lot, the plan fails.

More than any of that, even, the team must convince an old man that he is young again, both in appearance and stamina. It's a tall order. They are asking not only his mind to sabotage his sense of reality, but his body to do the same.

Doug (Sam Elliott), in his final appearance on the seires uses medicine to temporarily stop the pain in Kroll's aged, bum knee, and provides him a latex mask of youth that will last, precisely, six hours.

All the details must be perfect in the studio lot version of 1937, and at one point Jim Phelps sees an "extra" wearing 1970's style sun-glasses and rips them off his face abruptly.

Adding tension to "Encore," Kroll's partner, Stevens, is aware that he has been kidnapped, and on the look-out for him. So the IMF team must get Kroll to reveal the location of the body, and they have two deadlines. First is the six hour make-up duration. The second is the circling Stevens, getting ever closer to the movie lot.

A few things make this audacious episode work, and, finally, feel believable.

The first is William Shatner's brilliant performance as Kroll. He doesn't let the gangster fall for the trick at first. That would make him seem gullible, and an easy mark. Instead, as the IMF team walks the mobster through a series of "clues" that make 1937 seem real, Kroll relents, but a little at a time. A great moment occurs mid-way through the story when Kroll hears a plane flying by overhead, from his apartment. He looks up from his window, and sees a plane above. Amazingly, it is a plane appropriate to the 1930's era. In other words, it is not a flaw in the plane, it is part of the plan! Phelps has thought of everything, including stopping flyovers of modern planes, and providing for the flyover by the older plane. This meticulous detail, one can see on Shatner's face, is the thing that sells the idea of Kroll time traveling back to 1937. Who would possibly go the trouble of having an era-accurate plane fly overhead, apparently at random?

Only Jim Phelps, who apparently has a huge budget to run his intelligence ops, given what he pulls off in "Encore." Think about it. There's the plane flyover. There are dozens of extras. There are 1930's era cars. There's the complete make-over of two city blocks on the studio lot. There are the perfectly timed tape recordings of 1937 baseball games for the radio, and more.

But it is the denouement of "Encore," perhaps, which makes the episode so memorable in this M:I canon. Jim, Barney, Willy and Casey get the information they need, and evacuate the studio lot, along with the extras who have been cast as 1930's denizens. After fingering the spot where he hid the body, Kroll walks out into a deserted metropolitan street. In minutes it has gone from bustling metropolis to ghost town. This is revealed in a stunning pull-back.

Kroll begins to realize what happens, and starts running, to escape the lot. As he runs, the medicine Doug gave him wears off, and he starts to limp, hobbled again by old age. Then, the make-up on his face begins to melt, and he is fully restored to old age, and to the present At just that moment, Kroll's partner, Stevens, finds him, and both men realize, without saying a word, the "impossibility" of the trap that has snared them. It's one of the most colorful and satisfying conclusions in the sixth season of Mission:Impossible.

"Encore" is a controversial episode of this series, because for some, it is really about mission or format creep near the end of the series' long run. They see the episode as an example of the series running out of good ideas. Most stories in the canon, after all, are grounded far more clearly in reality. The plots are usually based on playing the mark's assumptions against him or herself, and therefore psychological in nature.

By contrast, the plan in "Encore" is big, bold, brassy and wild. But the 1930's details, and the great (and largely forgotten) Shatner performance make this "mission" an unforgettable hour. I would argue this episode isn't representative of mission creep, rather some kind of go-for-broke example of creative inspiration.

Shatner Day: Thriller: "The Hungry Glass"

Thriller , The Hungry Glass," stars the great William Shatner, and is a kind of regional-based horror story of the supernatural variety. The tale is set in a chilly "New England autumn" and a sleepy seaside community. It is in this setting that photographer Gil Thrasher (Shatner) and his wife, Marsha (Joanna Heyes), purchase the Bellman house...an old mansion strangely devoid of mirrors

The Thrashers are upset to learn from locals that their new real estate purchase is not only the site of a fatal accident, but it may actually be haunted. It seems that the woman who once owned the home in the 1860s, Laura Bellman was so vain -- so obsessed with her own beauty -- that when she died, her spirit moved into any and every object that would cast a reflection, whether a mirror or a window.

The Thrasher's real estate agent, Adam ( Gilligan Island's Russell Johnson) attempts to assuage the couple’s fears, but soon Marsha finds a locked door in the attic. Inside, in the dark, is a room of more than-a-dozen mirrors. Laura is watching.

Almost immediately upon moving into their new home, Marsha and Gil are startled by images of Laura's ghost, the woman in the mirror. beckoning to them. She is trying to "break through," to "reach you" and there is no doubt that she is murderous.

The terror builds and builds in "The Hungry Glass" until the malevolent ghost pulls unlucky Marsha into the looking glass with her, leaving her husband to destroy the mirror. Before the episode ends, there's another shocking death too.

This Thriller episode features some remarkable visual compositions. As the show commences, we get a view of the vain homeowner, Laura -- a beautiful woman. Or rather a view of her reflection, for she is seen only through a row of mirrors mounted on the wall. We move with Laura as she dances and plays to the looking-glass, and our vision of this character hops from mirror to mirror as she whirls and spins. In each mirror, we ponder, exists a universe unto itself. Then, when Laura is forced by circumstances to open the front door, we see the real Laura for the first time: an elderly hag who looks like she's already been embalmed, in the words of the teleplay.

Of course, we also get a great Shatnerian performance here.

In fact, Shatner plays the same type of character he has played in other contemporary genre anthologies: vulnerable but strong. For some reason, his "horror" characters always have feet of clay, and Gil Thrasher is no exception. In Twilight Zone's "Nick of Time," Shatner's newlywed character became paralyzed because of his superstitious nature. In "Nightmare at 20,000 Feet," Shatner was (again) a married man with a problem: he had just suffered a nervous break down so no one believed him when he claimed to have seen a gremlin on the wing of a plane in flight. If you think of Shatner's bomb de-fuser in One Step Beyond's "The Promise" and also his imperiled astronaut in The Outer Limits' "Cold Hand, Warm Heart," you see the same combination of vulnerability and strength showcased.

"The Hungry Glass" is exactly the same.

Here, Gil is a Korean War veteran who experienced hallucinations and also "the shakes" after his tour of duty ended. Now, when he begins to experience hallucinations again in the Bellman House, Gil's wife is doubtful about his sanity. And as the episode builds to its inevitable climax, Shatner's character gets closer and closer to the edge and, finally, goes over it in most dramatic fashion.

As the lead, Shatner is saddled with a lot of exposition in "The Hungry Glass," but he's marvelous in such scenes because it's clear his character -- while delivering words about Laura's after-life -- has become a shattered basket case. Shatner gets a faraway look in his eyes as he recounts Laura's final disposition, and it's clear he's lost his grip on reality.

And yes, Shatner does get to scream in "The Hungry Glass." So in his horror anthologies, I think he's three for four in that category.

"The Hungry Glass" is also filled with ironic commentary about mirrors.

"Mirrors never lie," "mirrors bring a house to life," "Every time you look in a mirror, you see death," etc., and Boris Karloff's ghoulish introduction gets in on the fun too. He notes to the audience that it should "make sure that your television casts no reflection..."

It really is enough to give you a chill.

Douglas Heyes directed several classic, timeless Twilight Zone episodes including "The Howling Man," "The Invaders" and "Eye of the Beholder." Thriller's "The Hungry Glass" is right up there with the best of those in terms of presentation and impact.

A pervasive sense of evil hangs over the Bellman House, influencing everything. Those who survive the night bid a hasty exit from the haunted mansion, never to return. But as a viewer, this is one haunted house you'll definitely want to re-visit, especially with Shatner as your twitchy tour guide.

Shatner Day: Twilight Zone: "The Nick of Time"

We'll start here, with a Twilight Zone episode starring the Shat: "Nick of Time."

"Nick of Time" is a Richard Matheson story, and one of my all-time favorite installments of the 1959-1964 Rod Serling series, The Twilight Zone. There are flashier shows, there are scarier shows, but I really enjoy how ambiguous this story is.

"Nick of Time" is the story of Don S. Carter (William Shatner) and his new wife, Pam (Patricia Breslin). Their car has broken down on their honeymoon trip to New York, and the couple is forced to make a pit stop for repairs in the sleepy little town of Ridgeview, Ohio.

It is there, in the Busy Bee Diner, that this couple will -- according to narrator Serling -- find "a gift most humans will never receive," the ability to "learn the future."

Why? Well, because this town and this diner rests on "the outskirts" of The Twilight Zone.

Our central character Don is an interesting guy, and Shatner's performance here is one of his best. Don's the superstitious type, with a rabbits foot on his key chain right beside a four-leaf clover. He is given to expressing himself in phrases such as "keep your fingers crossed."

"It's like you married an alcoholic" he admits to Pam in one of his more lucid moments, aware of how superstitious he really is.

But on now to Don's unusual nemesis. It's a rinky-dink napkin dispenser with a Devil Bobblehead perched on top. It's the "one cent" "Mystic Seer," a fortune telling-device that for one penny will read you your future. It does so by ejecting little cards that cryptically answer yes or no questions.

Sounds harmless enough, right?

Not so fast...

First, the machine accurately predicts that Don will get the promotion he's been waiting for.

Then it reports that the couple's car will not take four hours to be repaired, as was told the couple.

Don grows ever more convinced that the "gizmo" is actually telling him his future. "Why was it so specific?" He asks Pam. "Every answer seems to fit," he insists.

Pam isn't so sure.

And then things get really spooky. Don asks the machine if something will happen to the couple if they leave town. The answer: "if you move soon."

He then asks, "should we stay here?"

The answer: "that makes a good deal of sense."

Finally, Bob interprets a message from the Devil Bobblehead to mean that he and Pam shouldn't leave the diner until after 3:00 pm that afternoon.

Pam objects and forces Don to leave the diner. At one minute to three, on the street outside, they are nearly run over by a speeding car...

Convinced and stubborn, Don returns to the diner and begins asking the Mystic Seer more questions, even though Pam begs him not to. "You made up all the details, and all that thing did is give back generalities," she tells him.

He still won't leave. Not until his new wife tells him that the machine is running his life, and that she can't be married to a man who "believes more in luck and fortune" than in himself.

Don and Pam escape this trap, what Serling terms "the tyranny of fear and superstition," but in the episode's final shot, we see that another couple isn't so lucky. "Can we ask some more questions today?" They ask the machine.

"Do you think we might leave Ridgeview today?"

"Is there any way out?"

So again, in the most wonderful and entertaining terms imaginable, The Twilight Zone has presented us with a morality play of sorts, one about human nature.

Yet what's so enjoyable about "Nick of Time" is that we don't know whether Don is right (and the Devil machine is predicting the future), or if, in fact, he's merely superstitious and all the right answers are mere "coincidence" as Pam suggests.

The ultimate point is, I suppose, what you choose to believe in: fear or hope. You can choose to believe that you are small and in danger; or you can take control of your life and face the hardships with strength, and with the ones you love at your side.

Beyond a fortune telling device that may or may not be supernatural, there is no overt fantastical element in this installment of the Twilight Zone and yet it is oddly effective, and affecting despite this fact.

Visually, it's assembled in clever fashion by director Richard Bare. The first shot of the episode is a wobbly view from a tow truck bed, looking down from a high angle at the car being towed, with Don and Pam inside. This is an important view, because it establishes right from the beginning of the episode that Don is not "driving" his life (nor his car). He's simply being pulled in one direction or another, towed by his fear and superstition.

Later, when the couple first enters the Busy Bee Diner with the Devil Bobblehead/Mystic Seer, the camera views Don and Pat from the far side of a lattice-work room separator/divider, a sort of visual frame-within-a-frame signifying entrapment or doom.

This same camera set-up recurs at several important moments in the show.

The first time, we view two other local residents in thrall to the Mystic Seer at the dining booth, also through this "entrapment" lens (the criss-cross frame of the lattice).

Finally, when Pam encourages Don to summon his inner courage, the shot has changed to reflect their strength. The lattice wall is no longer between camera and character -- a visual obstacle and blockade -- but rather behind the characters. They have escaped the trap. They have moved literally past it.

I also get a kick out of the extreme (and I mean, EXTREME) close-up shots of the Devil Bobblehead, always jittering ever so slightly but nonetheless playing his Satanic cards close to the vest. He's an interesting villain because he's inanimate and yet we "impose" some sense of fear or personality on him.

If it were just a napkin dispenser, minus the Bobblehead, this episode wouldn't work nearly so well.

Shatner's performance is so good because he plays a character suffering from a lack of confidence. That's funny, given that he's the guy who plays Captain Kirk, but I would argue that even there, in Star Trek , that's the quality that makes the character work so well. Kirk is a human being, a leader of men, but he still second guesses himself ("Balance of Terror") or fears losing his job ("The Ultimate Computer").

Watching early Shatner performances you get a sense at how deft the actor is in playing a likable yet vulnerable character. He doesn't quite reach the heights of hysteria in "Nick of Time" that he would achieve later in "A Nightmare at 20,000 Feet," but the script calls for different things. I really like Shatner in this kind of every man persona. To me, he represents the perfect 1960s young male: a self-aware, intelligent, resourceful, JFK-type with just enough self doubt and neurosis to make him thoroughly disarming.

I find it fascinating that Shatner's two Twilight Zones and one Outer Limits ("Cold Hands, Warm Heart") place the actor in the thick of a couple relationship in crisis. He's always playing a husband dealing with something terrible, and trying to convince his wife that he isn't insane. Gremlins on planes, Venusians on "Project Vulcan," or a fortune telling machine that may be the Devil Himself.

March 20, 2025

Guest Post: Heart Eyes (2025)

Heart Eyes Warms The Heart, Then Stabs It to Pieces

By Jonas Schwartz-Owen

Sometime the WHO matters. It does in a whodunit, where the audience is invested in the crime, and it does in a who’s done it (as in who are the creators). Had Heart Eyes been written and directed by a newcomer, it would show a glimmer of hope for a future career. However, the script was co-written by the inventive Christopher Landon, creator of Happy Death Day 2U and Freaky, two smart, breezy comedy horror films with sly concepts and witty execution. The film was helmed by Josh Ruben, whose Werewolves Within and Scare Me were delightful, original horror comedies. Heart Eyeslacks the ambition and the skewed approach one expects from Landon and Ruben. Pretty much anyone competent with a film school degree could have made this film.

Melding the rom-com and slasher genres, Heart Eyes follow two attractive colleagues (Olivia Holt and Scream series dude-in-distress Mason Gooding) as they are targeted by a serial killer who slaughters couples on Valentine’s Day. The killer mistakes them for a couple, and, like cupid, sets up his arrow, but as a lethal weapon.

The script, which besides Landon, was also written by Phillip Murphy and Michael Kennedy, follows many of the elements in the Sandra Bullock romantic comedy milieu. Our protagonists, young Ally (Holt) and Jay (Goodling) meet-cute over a cup of coffee and are instantly charmed, only to discover they’re now competitors at their cutthroat marketing firm, so they hate each other. A life in jeopardy makes Jay more attractive and Ally finds herself falling in love. Her stubbornness leads him to disappear from her life, only for Ally to finally acknowledge that love, and chase him through the city to the airport for that romantic kiss. It’s perfect ‘90s comedy, except with buckets of gore.

If the movie’s rom-com aspects are Pitch Perfect (pun intended to those who recall the Jennifer Aniston comedy), the film’s parodying of ‘90s horror conventions is less on target. The film begins with our pre-credit victims, usually a big star (Drew Barrymore, Jada Pinkett-Smith, Kristen Bell/Oscar Winner Anna Paquin in the Scream franchise) or someone with cache (like Natasha Gregson Wagner in Urban Legend or Joseph Gordon Levitt in Halloween H20). No offense to Alex Walker and Lauren O'Hara, but both are unrecognizable and limited actors and don’t start the film out with a bang. The killer is also obvious, with a murky and bland motive. It almost feels like the real antagonist had been revealed on the internet à la Scream 2 and they quicky reshot a new villain and motive.

There are some gnarly kills, including one in the backseat of a car that is a variation on both a famous skewering from Death of The Twitch Nerve and a “holy” view from the remake of Texas Chainsaw Massacre. The killer’s mask, two glowing hearts, is visually creepy, while also comic. The authors also subvert the useless authority trope found in Last House on the Left, amongst others.

Holt and Goodling lend charm to their roles and build legitimate chemistry. The always delightful Michaela Watkins is doing her best Parker Posey impression as a high strung, browbeating Southern boss. There are also roles for ‘90s horror starts Devon Sawa (Final Destination) and Jordana Brewster (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning) that are tongue in cheek.

Though a solid enough horror comedy, with some enjoyable moments, Heart Eyes could have been something special. Both Christopher Landon and Josh Ruben have proven they think miles outside the box. Heart Eyes just isn’t subversive enough.

March 15, 2025

50 Years Ago: A Boy and His Dog (1975)

In 1975, the late Harlan Ellison's award-winning short story, "A Boy and His Dog" (featured in the 1969 collection called The Beast that Shouted Love at the Heart of the World) was adapted to film by actor L.Q. Jones, a relatively novice director.

You may recognize Jones' name because he's a talented actor who has appeared in films as diverse as Casino (1995) and A Prairie Home Companion (2006) and he wrote the truly amazing (and deeply underrated) 1971 horror film, Brotherhood of Satan.

A low-budget production that nonetheless expertly forecast a post-apocalyptic vision quite similar to the one depicted in Mad Max, A Boy and His Dog proved to be an authentic triumph for Jones; in turns quirky, absurd, and in some surprising moments...even oddly heartwarming.

Today, it turns fifty years old.

The story goes something like this: the year is 2024 AD, and Vic (Johnson) is an impulsive and callow scavenger living in a ruined, post-apocalyptic Arizona, following World War IV...which lasted five days. Vic is accompanied on his journeys by Blood, a canine with whom the lad shares a most unusual telepathic link. In other words, Blood and Vic talk to each other, and the dog -- whose main purpose is to procure women for Vic and help the young man avoid the roving "Screamers" -- is by far the smarter and more experienced of the two beings. But Vic doesn't always listen to the dog, and that causes problems.

Case in point: Vic really, really wants to get laid. It's been six weeks since he's been with a woman, and he's getting desperate. At a local showing of an old porno film in an open air venue, Blood informs Vic that he smells a lone female in the audience of homeless, pitiable people. Vic tracks her down, and this is how he first encounters Quilla June Holmes (Susanne Benton), a beautiful and willing woman from the unseen world "down under,” a civilization beneath the surface of the desert. After Vic and Blood save Quilla from a gang of attacking Screamers, Quilla attempts to entice the head-strong, independent Vic to her mysterious world. But Blood is badly injured, and begs Vic not to go. Fired up about Quilla June, Vic decides to ignore the dog's advice and visit the subterranean world of Topeka. It's a creepy kind of 1950s Ozzie and Harriet "nightmare" civilization where everyone is so pale from lack of sunlight that they've taken to adorning creepy white pancake make-up. The town is run by an organization called The Committee

Topeka has big plans for Vic. They plan to make use of "the fruit" of his "loins." Turns out Quilla June was sent to lure him to the underground world. The women there can no longer get pregnant by the male citizenry of the little burg, and they need a man from above to get the job done. Vic thinks this is a dream assignment -- obviously -- until the exact details are made clear. There will be no intercourse. So instead, he's attached to a painful looking sperm extraction device, and it's here...filling one vial of semen after another...that he'll spend the rest of the days. A line of 35 blushing brides in gowns wait outside Vic's medical theatre nervously expecting his…fluids..

When Quilla realizes that the Committee has double-crossed her and has no plan to make her a senior member of the organization, she helps Vic escape. Vic can't wait to get back to his dog, to his life on the surface. "I gotta get back in the dirt...so I feel clean," he quips. Back on the surface, a dying (but loyal...) Blood awaits. Vic is forced to make a tough decision to keep Blood alive. He must choose between a treacherous woman...and a beloved dog.

Generally well-received, A Boy and His Dog nabbed a Hugo for best dramatic production and was also nominated for several other awards, including ones from The Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films, and The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America. Despite these honors, some critics also concluded that the film (advertised with the tag-line "a rather kinky tale of survival") was a misogynist effort, a judgment based almost entirely, it seems, on the film's final line of dialogue.