Rod Dreher's Blog, page 618

February 2, 2016

Teen Love In The Ruins 2016

New in the Young Adult section, a novel called Firsts. From the publisher MacMillan’s description:

Seventeen-year-old Mercedes Ayres has an open-door policy when it comes to her bedroom, but only if the guy fulfills a specific criteria: he has to be a virgin. Mercedes lets the boys get their awkward fumbling first times over with, and all she asks in return is that they give their girlfriends the perfect first time-the kind Mercedes never had herself.

Keeping what goes on in her bedroom a secret has been easy – so far. Her mother isn’t home nearly enough to know about Mercedes’ extracurricular activities, and her uber-religious best friend, Angela, won’t even say the word “sex” until she gets married. But Mercedes doesn’t bank on Angela’s boyfriend finding out about her services and wanting a turn – or on Zach, who likes her for who she is instead of what she can do in bed.

When Mercedes’ perfect system falls apart, she has to find a way to salvage her own reputation -and figure out where her heart really belongs in the process. Funny, smart, and true-to-life, Laurie Elizabeth Flynn‘s Firsts is a one-of-a-kind young adult novel about growing up.

You can read the book’s first chapter here. It’s soft-core porn. Here’s more, from inside the book. I’m going to put this below the jump, to spare those who would rather not see it. I think it’s important that you see it to know what’s out there. Keep in mind that this does not come from a pornographer, but from a major publishing house — and it is recommended from girls as young as 14:

“The kitchen?” he says when I press him against the stainless steel refrigerator. “I never did it in a kitchen before.” He grabs me around the waist and lifts me onto the granite counter, where he puts his hand up my skirt and pulls my panties off. The counter happens to be the perfect height for sex, a fact I never noticed until yesterday morning, when I bent over it to paint my nails and purposely mess up Kim’s [her mother’s] daily ritual of polishing the granite. This has been on my mind ever since, taunting me in prayer group and distracting me all through chemistry. This is a regular occurrence for me, using Zach to play out my little fantasies. Somehow I don’t think he minds being a guinea pig.

“These are my favorite,” he says, clutching my pink lace panties in his hand. All of my panties are either lace or satin or sheer — no dingy whites or high-waisted monstrosities. I don’t even want to know what those would do to my reputation. Lucky for me, Kim tossed out all my childish floral panties back in elementary school, the day I got my period and she decided I needed something more grown-up.

Zach lets his own pants fall to the floor and abruptly closes the gap between us. He stands right between my legs, ready to go — until I reach out and slap him in the face.

“Condom, Zach,” I say, snapping my fingers. “You didn’t want to make it upstairs, so you should be ready.”

“Come on,” he says, leaning in to bite my lip. “I’m clean, you’re clean. I got tested six months ago. And we’re not sleeping with other people. It would feel so good without it.”

Ah, young love.

I’ve been sitting here staring at my screen for a while, trying to figure out what to say about this. I’m at a loss. I suppose the thing that gets to me the most is the idea that what was not too long ago the kind of thing that appeared in smutty adult novels is now packaged and sold by mainstream publishers for eighth grade girls. The culture wants to make whores of its daughters, and to debauch its sons.

Well, this Weimar America culture can go to hell if it wants to, but it’s not going to take my children with it, if I can help it. The author of this book and its publisher are barbarians. Philip Rieff called this kind of thing “anti-culture.” Culture, as he saw it, was a process through which people learned to bind and to loose, to form their souls to a higher order — a “sacred” one, he called it, though he was not a religious believer. This sacred order allows life to continue. It is generative, and regenerative. An “anti-culture,” then, is one that destroys all possibility of order, and of the generation of life.

We live in an anti-culture. It’s killing itself. Firsts is a small thing, but its importance lies in its banality. This is the poison we feed our children as their daily bread.

The ancient Hebrews knew the truth, and that truth endures forever. From the book of Deuteronomy, Chapter 30:

15 See, I set before you today life and prosperity, death and destruction. 16 For I command you today to love the Lord your God, to walk in obedience to him, and to keep his commands, decrees and laws; then you will live and increase, and the Lord your God will bless you in the land you are entering to possess.

17 But if your heart turns away and you are not obedient, and if you are drawn away to bow down to other gods and worship them, 18 I declare to you this day that you will certainly be destroyed. You will not live long in the land you are crossing the Jordan to enter and possess.

19 This day I call the heavens and the earth as witnesses against you that I have set before you life and death, blessings and curses. Now choose life, so that you and your children may live 20 and that you may love the Lord your God, listen to his voice, and hold fast to him. For the Lord is your life, and he will give you many years in the land he swore to give to your fathers, Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.

I have a friend who, many years ago, was badly strung out on cocaine. One day, when he was out driving around Los Angeles, he heard a voice say, “If you want to live, stop it.” Just like that. He stopped it. He lived, and now he thrives. I feel like that when I come across filth like Firsts. If we want to live, we have to stop it, turn away from this darkness, and go to the light.

February 1, 2016

Iowa Winners, Iowa Losers

WINNERS

Ted Cruz, who not only did what he had to do to stay alive, but also, by winning outright, embarrassed Trump mightily.

Marco Rubio, whose surprisingly strong third place finish — a whisker behind Trump! — makes him the undisputed establishment candidate, and delivered a massive shot in the arm to his campaign. There is now no reason for candidates who polled behind him to stay in the race. Their supporters reasonably ought to coalesce around Rubio (except Carson voters, many of whom will probably drift Cruzward).

LOSERS

Hillary Clinton, former Secretary of State, dynast, and the presumptive Democratic nominee since forever, was very nearly knocked off by an elderly New England socialist. (And may yet be, but it’s late, and I’m not going to wait for that last five percent of Democratic votes to come in.) It’s impossible to see how she loses the nomination, but my gosh, even if she pulls this out tonight, what an incredible humiliation for someone of her stature within the Democratic Party. This:

Blowing a 53.8 lead in 12 months is a loss, no matter how you try to spin it.https://t.co/G22WyGfSqu

— Connor Walsh (@wconnorwalsh) February 2, 2016

Donald Trump, who got his nose bloodied. He’s still got the most momentum going into the next primary states, and he was always expected to do less well in Iowa, a caucus state that rewards ground organization (of which Trump had bupkis; if you think about it, it’s still something else that he came in 2nd). But he has lost the psychological advantage over his rivals that he’s held for months. He looks vulnerable. Had Trump won Iowa, it would have been possibly a mortal wound for Cruz.

Jeb Bush, who polled a miserable 3 percent in Iowa, spent a reported $25,000 per caucus vote. Hey, he’s still got $59 million to burn through, but they don’t have trailer hitches on hearses. The Bush political dynasty died tonight on the Midwestern plains.

UPDATE: Six months ago, if you had said that the Iowa caucus would end with 1) Vermont socialist Bernie Sanders tied with Hillary Clinton, 2) Donald J. Trump coming in second on the GOP side, and 3) Jeb Bush bottoming out with 2.8 percent of the vote, who would have believed you?

Matt Yglesias is not happy with the Democratic establishment tonight. Excerpt:

The Clinton campaign’s strategy will, of course, be second-guessed as stumbling front-runners always are. But the larger problem is the way that party as a whole — elected officials, operatives, leaders of allied interest groups, major donors, greybeard elder statespersons, etc. — decided to cajole all viable non-Clinton candidates out of the race. This had the effect of making a Clinton victory much more likely than it would have been in a scenario when she was facing off against Elizabeth Warren, Joe Biden, and Deval Patrick. But it also means that the only alternative to Clinton is a candidate the party leaders don’t regard as viable.

Trying to coordinate your efforts to prevent something crazy from happening is smart, otherwise you might wind up with Donald Trump. But trying to foreclose any kind of meaningful contact with the voters or debate about party priorities, strategy, and direction was arrogant and based on a level of self-confidence about Democratic leaders’ political judgment that does not seem borne out by the evidence. This is a party that has no viable plan for winning the House of Representatives, that’s been pushed to a historic lowpoint in terms of state legislative seats, and that somehow lost the governors mansions in New Jersey, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Illinois.

It’s a party, in other words, that was clearly in need of some dialogue, debate, and contestation over what went wrong and how to fix it. But instead of encouraging such a dialogue the party tried to cut it off. That leaves them with Sanders’ Political Revolutiontheory. It doesn’t seem very plausible to me, but at least it’s something.

A lot of us have been focused for the past week or two on what the Trump phenomenon says about the intellectual bankruptcy of the GOP. The Sanders phenomenon is not nearly as colorful or as fun to think about, but Bernie is quietly making a very similar point to Donald Trump’s, on his own side. Yglesias gets it.

Ted Cruz Is Not What He Seems

Here’s a really interesting piece by Erica Grieder, a writer for Texas Monthly magazine, in which she gives Ten Things You Ned To Know About Ted Cruz. Fascinating stuff. Among them:

1) Ted Cruz is not a fire-breathing extremist.

Cruz, obviously, is a polarizing figure, for several reasons. One is that he is perceived as a hard-line conservative, if not a genuine extremist. This is a misconception that he has encouraged, by casting himself as someone outside the party establishment, to the right of his colleagues. He campaigned in 2012 as a Tea Party insurgent and has staged numerous fights in Congress, in opposition to the so-called conciliators of the surrender caucus. He is now stumping around Iowa, denouncing the “Washington cartel.”

There’s no question that Cruz is a conservative. On constitutional issues, I’d say he’s the gold standard. But he’s not as extreme or ideological as people often assume. Maggie Wright, a Texan who has traveled to Iowa to volunteer, gave journalist (and Texas Monthly contributor) Robert Draper an admirably concise summary: “He’s for states’ rights, for all the Constitution, he will not allow us to bash the gays but won’t let anybody do jihad on the Christians.” Similarly, though Cruz is one of the few Republicans in Congress who passes muster with the right wing’s self-appointed purity czars, and he is contemptuous of conservatives who assert principled convictions they do nothing to advance, he is ecumenical about disagreement. “In any two-party system you welcome people with a variety of views,” he told me in 2013, after I asked if the Republican coalition could include leaders who support gay marriage, or even abortion rights. And Cruz is not the kind of partisan who casts his opponents as evil or stupid; his provocations are more subtle. In 2013, having described Barack Obama as an “honest-to-god socialist,” he added that he was using the word in its literal sense: “It describes a means of structuring an economy. Socialism is government ownership or control of the means of production or distribution.”

Because Cruz is currently running for the Republican nomination, the perception that he is a ferocious hard-liner serves his interests, and he’s not likely to dispute it. But even on the campaign trail, fielding questions from the grassroots, his answers are more nuanced than his reputation would suggest. As the campaign goes on he is likely to devote more attention to issues such as economic opportunity, which he emphasized in a January 2013 speech, shortly after being sworn in to the Senate.

Another one:

4) Cruz is smarter than us.

I’m not ideological about intelligence. In my view, it comes in many forms and none of them have a moral valence. So when I say that Cruz is smarter than us, I don’t mean it to imply a value judgment or even a contrast with other politicians. What I mean is that Cruz has the particular form of intelligence that is universally recognized as such, and he has it in abundance. This is just how it is. I feel no need to deny it, and I see no purpose to doing so.

Instead, I proceed on the assumption that Cruz is smarter than me—not that he’s a superior human who Americans should follow blindly, and not that he’s always right. Just that he’s smarter than me. In practice, that means when Cruz says or does something that doesn’t make sense to me, I ask myself what I’m missing. I take a step back and slowly puzzle through why a very smart person with certain well-documented strategic objectives would do that. Lord knows this is not my usual practice with politicians, but it has turned out to be a surprisingly effective technique for analyzing Cruz. I highly recommend it.

Read the whole thing. It changed the way I see Cruz. Didn’t make me care for him any more than I do, but it did make me take him a lot more seriously. Grieder concludes:

The day he announced his campaign, I learned two things. Cruz sees a path to the presidency. And the path exists.

Readers who can’t see it yet shouldn’t feel bad. It took a lot of people in Texas a while to see Cruz’s path to the Senate, too. Whether his risky bet pays off this time is yet to be determined and subject to circumstances, some of which can’t yet be anticipated, and some of which are unavoidably out of his control. But he’s already come much further than his critics thought he could. He clearly has a chance. Cruz, I have no doubt, knew that long ago.

Vote Like Jesus Would, Sez Ted

Cruz’s stump speech is by far the most religious one of all the Republican candidates, in which he tells his supporters to pray “each and every day” until the November election.

At a campaign stop in Hamlin, Iowa, before the caucus, he told supporters that it’s time to, “awaken the body of Christ that we may pull back from the abyss.”

For non-Christians in the readership “the body of Christ” here refers to the church universal. He’s telling his Christian supporters that the country is going to hell in a handbasket, but if they wake up and “vote [their] values,” they might turn things around.

CBN’s Brody File has a clip of a recent private Cruz address to Iowa pastors. He’s really good on the stump. At just past the one minute mark, Cruz admonishes his audience to caucus for the candidate who “defends Biblical values. … The people who burn us tell us they agree with us. So don’t listen to what they say or what I say. Don’t listen to what I say! Hold us to the test. Hold us accountable.”

You might have missed this Politico report from December 23, based on a recording of a meeting Cruz had with some wealthy Manhattan donors. Politico reported:

During the question period, one of the donors told Cruz that gay marriage was one of the few issues on which the two disagreed. Then the donor asked: “So would you say it’s like a top-three priority for you — fighting gay marriage?”

“No,” Cruz replied. “I would say defending the Constitution is a top priority. And that cuts across the whole spectrum — whether it’s defending [the] First Amendment, defending religious liberty.”

Soothing the attendee without contradicting what he has said elsewhere, Cruz added: “People of New York may well resolve the marriage question differently than the people of Florida or Texas or Ohio. … That’s why we have 50 states — to allow a diversity of views. And so that is a core commitment.”

The donor was satisfied, ending his colloquy with Cruz with a friendly: “Thanks. Good luck.”

A well-known Republican operative not affiliated with a 2016 campaign said by email when sent Cruz’s quote: “Wow. Does this not undermine all of his positions? Abortion, Common Core — all to the states? … Worse, he sounds like a slick D.C. politician — says one thing on the campaign trail and trims his sails with NYC elites. Not supposed to be like that.”

Cruz’s campaign responded that the candidate is not dissembling here, that the “leave it to the states” view has always been his this cycle. Mike Huckabee has accused him of talking out of both sides of his mouth, but the truth is, neither of them are being straightforward with voters. You’d think that the Obergefell ruling had never come down. What they’re doing is virtue-signaling to Evangelical voters. It doesn’t matter if they would “leave it to the states” or not; SCOTUS has made same-sex marriage a constitutional right. I don’t like it any more than Ted Cruz does, but it has happened, and there’s no realistic prospect of overturning that ruling, which, alas for us all, is popular.

Same-sex marriage is here to stay. The question now is what happens to the religious liberties of institutions and individuals who dissent from the new orthodoxy. That is something that the president and Congress do have some say over, if they have the vision and the courage to act, and act with strategic intelligence.

Yesterday in Iowa, Phil Robertson of Duck Dynasty fame warmed up a Cruz crowd:

Robertson said Cruz was the only candidate who could restore the constitutional and biblical foundation of government.

“When a fellow like me looks at the landscape and sees the depravity, the perversion — redefining marriage and telling us that marriage is not between a man and a woman? Come on Iowa!” Robertson said.

“It is nonsense. It is evil. It’s wicked. It’s sinful,” he said to applause. “They want us to swallow it, you say. We have to run this bunch out of Washington, D.C. We have to rid the earth of them. Get them out of there.”

“Ted Cruz loves God, he loves James Madison and he’s a strict constitutionalist. You know what Ted Cruz understands,” Robertson said. “God raises these empires up. It is God who brings them down.”

It’s all so easy, isn’t it? Vote Ted, rid the earth of evil, and all will be well. Why does anybody believe this stuff anymore?

“The people who burn us tell us they agree with us,” Cruz told those pastors. The implication is that they’re lying, that they really don’t agree with the Evangelicals. I don’t believe that’s what Cruz is guilty of. What he’s guilty of is misleading Evangelicals into thinking that by electing him, they will be casting a vote for getting rid of same-sex marriage. I wish that were possible, but it’s not — and Scott Shackford, the gay libertarian, explained very well why the GOP candidates running on this issue are blowing an opportunity to defend religious liberty. So what we have here is the same old Religious Right song-and-dance. Vote for me and I’ll re-moralize America.

It’s untrue. Politics cannot do the work of culture.

UPDATE: Here’s a column by Francis Beckwith criticizing Evangelicals who have jumped on the Trump bandwagon. Great final graf:

And Trump is a damn good preacher. So much so that many evangelicals don’t seem to notice the un-Christian personal insults, slurs, arrogance, mendacity, and incoherence. Which just goes to show you that not only is a sucker born every minute; sometimes he’s born again.

UPDATE.2: I can’t decide if it’s more unnerving to think that Ted Cruz doesn’t really believe what he’s saying … or that he does.

January 31, 2016

Character Is Destiny, But Not Straightforwardly

Michael Gerson writes in the Washington Post:

Leadership is often evidenced in relatively small things. Shortly after his election in 2000, I was with President George W. Bush in the family theater at the White House where he was practicing his first address to Congress. For whatever reason, the military is charged with teleprompter operation, and the operator had messed up his job. An angry Bush said, “Call me when you get your act together” and stalked out of the room. The young man was distraught. But a few minutes later, Bush returned and apologized to the operator, saying: “That is not the way the president of the United States should act.”

A small thing, but I remember it. The office confers an awesome power to elevate the lives of those around a president, or to destroy them.

And therefore, we shouldn’t vote for Donald Trump, who is a total jerk.

This is what’s so frustrating about the Trump thing. I think George W. Bush is exactly the decent man Gerson says he is. And I think Trump is just as piggish as Gerson says he is. What’s more, I agree with Gerson that temperament in high office matters.

And yet, all of Bush’s personal decency did not stop him from making colossal errors in judgment, most of all with Iraq, but not only with Iraq. That honorable gentleman, George W. Bush — and I’m not calling him that snarkily, note well — blundered the nation into its worst foreign policy disaster since Vietnam. And all his personal decency did not stay his hand as a torturer. Jimmy Carter was probably one of the most decent men ever to hold the office, but it availed him nothing as a leader. Gerson cites Richard Nixon’s paranoia as an example of how a president’s temperament can affect his performance in office. He’s right: character really is destiny.

But it’s not always destiny in predictable ways, is it? The people who back Trump know he’s a jackass — and that’s what they like about him. They see it as a character strength, as in, “this guy is not going to let himself be taken advantage of, and he’s not going to let America be taken advantage of.” I think it’s a pretty serious risk to take, going with Trump, but holding up George W. Bush’s admirable gentlemanliness as a counterargument to Trump’s low character does nothing to bolster the case against Trump. Ronald Reagan was a famously nice guy, but by the end of the woeful Carter years, the American people were ready for an SOB, as long as he was a competent SOB.

Bunga Bunga Billionaire Nation

Ladies and gentlemen, from the Howard Stern Show, the odds-on favorite to be your Republican Party nominee for president, Donald Trump, in a long 1997 interview with shock-jock Howard Stern, in which he discusses, among other things, how he avoided sexually transmitted diseases, how he could have had Princess Diana, whether or not he masturbates and … well, watch the whole thing, but beware, it’s very NSFW.

Prior to Trump, it was impossible to imagine a presidential contender with this kind of thing in his past. [UPDATE: I mean a video of this kind of trashy discussion. — RD] Can you imagine the fun Democrats would have mining Trump’s endless vulgar statements for attack ads? As we now know, though, this is not a bug with Trump, but a feature. People either don’t mind it, or they appreciate how Trump just doesn’t give a rat’s rear end what people think of him. Watch that Howard Stern interview, and it’s easy to see Trump as an American version of Silvio Berlusconi, elected to office in Italy, in part because all his traditional party opponents were seen as weak and ineffectual. A friend and reader of this blog e-mails:

In one of your articles you ask if Trump ever loses.

Depends on what you call losing.

To some, he loses huge, but they don’t notice it really.

For most people, they don’t take the big risks because the big thing they are afraid to lose is popularity. They are afraid of losing the pats on the backs, the flattery, and the crap of human sentiment, and when I say “crap” of human sentiment, I do not mean human sentiment is crap. I mean, human sentiment that runs on emotion of whether I like you today because you kissed my a*s or not and gave me what I wanted and told me what I wanted to hear is crap. It’s nothing, and, yet, people are afraid to lose it. They are afraid of being criticized, not getting enough “likes” on their Facebook page, and being the bad guy. They are afraid to rock the boat because someone might suggest tossing them overboard. And if we are honest about it, those people are pandering to the populace because they have neither a solid moral compass or any real idea of who the hell they really are. They need the populace to talk to them because they need the populace to dictate identity.

Trump does not give a rat’s rear end about any of the above because he is none of the above.

He knows who he is. He knows what he stands for. He has a clear compass point for where he is and where he wants to go, and he doesn’t need anyone telling him he is right. And, if he gets tossed overboard, he’ll find another way to swim. He simply does not need the populace to be himself, and because of that, he bets big, and he wins big.

Does he ever lose? Actually, he loses big, too. He loses popularity because people don’t like his drive, his disinterest in others’ opinions, his unwillingness to bend to cater to others’ emotions or insecurities. The thing is, Trump doesn’t care because that isn’t a loss to him. He is looking beyond that. To other people, that is the greatest loss they can imagine, and it becomes their prison.

You and I both know a person cannot do great things without pissing off the general masses and their opinions. For most people, that is too much risk to take. For Trump, it never crosses his mind.

Look at the people shaping our world right now and think of how many think like Trump. How many are willing to rock the boat because they believe they are here for bigger purposes than popularity? Look at Franklin Graham and how outspoken he has become on hot topics. Is he Trump? Not yet, but politics is Trump’s realm, and we all know politics, not God, is America’s foremost religion now.

Rod, there is a lot to learn from Trump, not just in business or politics, but in the drive for what is worthy losing and what cannot afford to be lost…and fiercely we must be willing to battle for what we cannot afford to lose.

Now, we’ve all been talking about how almost nobody saw Trump coming. We’ve been talking about why people are drawn to Trump, and what the GOP Establishment failed to understand about itself. There are lots of theories going around, but I have not seen a Unified Theory Of Trump emerge yet — one that gets to the core of the Trump phenomenon.

Trump’s missing the final Fox debate before Monday’s Iowa caucuses seems to have paid off for him, as he has increased his lead over Ted Cruz, his nearest rival. Unless Trump can’t get his people to the caucuses on Monday night, he’s going to win Iowa, and he’s well ahead in the next two primary states, New Hampshire and South Carolina. If he wins all three, that will be an unprecedented feat.

Ron Brownstein says polling reveals the big new divide in the GOP: class. More:

The most consistent dividing line in responses to Trump is education. That was a telling differentiator in 2012, too: Romney won voters with at least a four-year college degree in 14 of the 20 states, but he carried most non-college voters in just ten of them. But this time the class divide has widened to become the race’s central fissure.

From the start, Trump has performed better in polling among Republicans without a college degree than among those who hold a four-year or post-graduate degree. Across the broad range of recent national and early state surveys, Trump consistently attracts about 40 percent of Republicans without a college degree—a remarkable number in a field this large. (The three latest Marist polls put him at 42 percent with them in Iowa, 41 percent in South Carolina and 36 percent in New Hampshire.) His performance among those with degrees is usually more modest: around 25 to 30 percent in most surveys.

Trump’s success at connecting with the economic and cultural anxieties of blue-collar whites largely explains why he hasn’t been damaged more by his disputes with groups that usually function as the gatekeepers for conservative support, from the Fox News Channel to National Review. Voters at Trump rallies are often quick to acknowledge he isn’t a typical Republican, or a classic conservative. Yet they don’t see his deviations from party orthodoxy as disqualifying because they view him as championing them against forces they view as threatening—from special interest influence in Washington to rapid demographic change. “I come out of a traditional Republican household,” said Tom Cotton, a retired law enforcement officer from Grinnell, Iowa, who attended a Trump rally in Marshalltown last week. “And let’s face it—he’s not a traditional Republican. But I truly believe he will give it everything he’s got to get things going again.”

Remember that line of populist Louisiana Gov. Edwin Edwards I posted not long ago? The one in which Edwards explained the mystery of why certain social and religious conservatives in Louisiana voted for him, despite his reputation as a womanizer and a crook?

“With me, the people know the butter might be rancid, but it’s going to be spread on their side of the bread.”

There you go.

New York magazine has a passage from its reporting on Iowa and New Hampshire voters that really resonates. Emphases below are mine:

This attraction to strength seems to be connected to an inchoate sense that the world is falling apart. The voters we spoke to were concerned about a lot of potential threats — terrorist, economic, and cultural — and hoped that a strong president would protect them from dangers within as well as from abroad. Voters said they no longer felt free to be themselves in their own country — policed in their speech, unable to pray publicly or even say “God bless you” when someone sneezes. “Everything’s so p.c.,” said Priscilla Mills, a 33-year-old hospital coordinator from Manchester. “And then the second you do say something, you’re a racist.” Trump, who had 21 percent of the vote in our small sample, has capitalized the most on the political-correctness grievance, which is likely to surface in the general election no matter who becomes the nominee.

The culture wars clearly aren’t defined along the same lines that they used to be. Almost everyone we spoke with said they were pro-life, but few talked about restricting abortion as their main issue. And gay marriage barely even registered as a cause for concern. “I feel like I don’t wear a black robe, so I don’t have the right to judge anybody,” said Tina Vondran, 49, of Monticello, Iowa.

Certainly, there were voters turned off by the polemical style of the more extreme candidates. And 48 percent were still undecided as of late January. But their leanings, which crisscrossed ideological positions, seemed to confirm the conventional wisdom that the GOP-primary voter is more motivated by mood than by policy. “Donald Trump has the best tagline of all, ‘Make America great again,’ ” said Rubio backer Russell Fuhrman of Dubuque, Iowa. “The country just seems to be in a severe decline. Insecurity’s so high; pessimism and political correctness are running rampant. It’s sad.”

More motivated by mood than policy. That’s an important insight. The people can’t really put their finger on what’s wrong, but they sense — correctly, in my view — that something is very seriously wrong. Trump gives them a sense that the problem is the Other (Wall Street, immigrants, et alia), and that by force of will, he will set things aright. It is way, way too easy to explain Trump away by saying he’s a scapegoater. He may well be that, but he’s not entirely wrong about how the architects of our economy in finance, industry, and in government, have worked against the interests of very many Americans just like them.

And this reaction against political correctness? Don’t you think these people know perfectly well that they and their values are despised by the cosmopolitans who run media, academia, the political parties, and so on? Boston University professor Stephen Prothero had an insightful remark on Facebook:

[The] Democratic Party also to blame, by ignoring the cultural concerns of working-class white voters. Bernie Sanders addresses their economic concerns, but he and HRC ignore their cultural concerns–their worry about losing their jobs to undocumented immigrants; their fear of terrorism. Trump addresses their economic concerns also by pledging to tax Wall Street traders (as Bernie has promised). But he speaks to their fears and their sense of not being heard or “protected.” Those of us who live in our white liberal bubbles in Boston or the Bay Area don’t see these people. They are like “dark matter” to us, pulling on the gravitational force of US politics but largely invisible. But now not so much.

All of this is true. But what’s also true, I think, is that people are fooling themselves if they think electing a strongman is going to save us. Dante Alighieri fantasized about a strongman coming to sort out the godawful mess that was Italy in the 14th century, but I think he told truer than he knew in Purgatorio XVI, on the terrace of Wrath. When the pilgrim Dante asked Marco the Lombard why the world back on earth is in such a mess, Marco answered him by saying, in effect, If you want to fix the world, first fix your own heart.

It sounds like a greeting card sentiment, but it’s not. Did you hear this story on NPR this morning, about the “collapse of parenting”? A psychiatrist and family physician has a new book out talking about how parents today are setting our kids up for failure by catering to them, giving them what they want, not what they need. And we have created a culture in which we tear down parents who try to do the right thing. Dr. Leonard Sax, the author, told NPR:

So, for example, one mom took the cell phone away because her daughter’s spending all her time texting and Snapchatting. And the daughter didn’t push back. And her friends were like “Oh, you know her mom’s the weird mom who took her phone away.” The real push back — and this is what surprised this mom — came from the parents of her daughter’s friends, who really got on her case and said, “How can you do this?” and this mom told me that she thinks the other parents are uncertain, unsure of what they should be doing and so that’s why they’re lashing out at her — the one mom who has the strength to take a stand.

Why would moms do that to the disciplinarian mom? Sounds like they’re doing it to assuage their own bad consciences. This is the kind of thing that politics cannot fix, this degraded parenting culture. Years ago, a friend of mine who worked as an elementary school teacher in a school filled with impoverished kids used to go to these kids’ houses after school to meet with their parents (or rather, almost always, the parent; there were no dads in these houses). He said over and over, it was the same thing: the TV was on all the time, blaring loud, and the mother was completely checked out. It was chaos externally, and (therefore) chaos inside these kids. My friend finally became so overwhelmed by the enormity of the problem, and the unwillingness of the parents to lift a finger to change the course of their children’s lives, that he quit teaching and went into another line of work. He saw no hope there.

Look, I’m not saying that policy (economic and otherwise) has nothing to do with this “things fall apart” situation we find ourselves in. It does. But there’s a lot more going on here, at every level of our society, from top to bottom. The center is not holding. Trump is not the cause; Trump is the effect. If he becomes president, maybe some things will change for the better, but if he threw out every illegal immigrant, built a wall between the US and Mexico, reformed the financial system and did everything he promised to do, We The People would still have massive problems governing ourselves, in our private lives.

From Brad Gregory’s history The Unintended Reformation, this reflection on what happens to us when we give up, or only pay lip service to, the religious beliefs undergirding the foundation of our democracy. Emphasis below is the author’s:

Overwhelmingly, through [churches] and their families [early Americans] learned their moral values and behaviors. Tocqueville saw this clearly in the early 1830s, and the most prominent nineteenth-century American Catholic intellectual, too, the convert Orestes Brownson, was from the mid-1850s keen on the way in which such remarkably empty rights could be filled with Catholic content. The American founding fathers intuited, for their own time, how a novel ethics of rights could assume without having to spell out or justify the widespread beliefs that socially divided Christians continued to share notwithstanding their divergent convictions. What they could not have foreseen was what would happen to an ethics of rights when large numbers of people came to reject the shared beliefs that made it intellectually viable and socially workable. They could not have imagined what would happen when instead, intertwined with new historical realities and related behaviors, millions of people exercised their rights to convert to substantially different beliefs, choosing different good s and living accordingly. Only then, especially after World War II and even more since the 1960s, would the emptiness of the United States’ formal ethics of rights start to become visible, the fragility of its citizens’ social relationships begin to be exposed, and its lack of any substantive moral community be gradually revealed through the sociological reality of its subjectivized ethics. Civil society and democratic government depended on more than deliberately contentless formal rights. But what would or could that “more” be, and where would it come from, if religion no longer provided shared moral content as it had during much of the nineteenth century?

We are living out the answer to that question, and will be living out for the foreseeable future.The American people are right to sense that things are falling apart, but they misunderstand the ultimate sources of the disorder. This country needs new and better political leadership; that is undeniably true. But at best, it would only solve part of the problem, and not even the most important part. More than anything right now, this country needs a new and quite different St. Benedict.

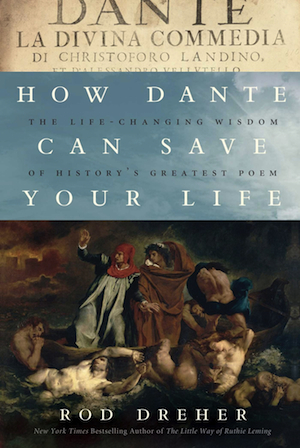

How Dante Can Make Your Lent

Image by Michael Hogue/Photo by Rod Dreher

I hear from time to time from people who say they liked my book The Little Way of Ruthie Leming, but they didn’t pick up How Dante Can Save Your Life because they don’t really care about poetry or literary analysis.

Well, I’m not much on poetry or literary analysis either. And How Dante is not the book they think it is.

You might call it “literary self-help” for people who don’t buy self-help books. I was (am) that kind of person. And I rarely buy books of poetry. I consider that a character flaw, but that’s how I am. Yet I stumbled into The Divine Comedy when I was lost, depressed, and sick as a dog. I believe that God used that incomparable poem to heal me. Through it, the poet Dante systematically led me on an examination of conscience, and revealed to me sins, and patterns of sinfulness, that I had concealed from myself. Through prayer, confession, therapy, and plain old repentance (the hardest thing!), I slowly found my way back to the straight path, and was restored. Dante, in his poem, showed me the way out of the dark wood into which my own failures, disappointments, and passions had led me. How Dante is a story about hard-won victory.

With Lent almost upon the Christian West, it occurs to me this morning that some of you might want to take up How Dante as part of your Lenten reading. There’s a little bit of literary analysis in it, of course, but the overwhelming thrust of the book is about how to apply the insights in the poem to your own life struggles. In my own case, there wasn’t a lot I discovered in the Commedia that I didn’t already know at some level — that is, in terms of right and wrong — but because Dante embedded these moral and theological truths, and truths about human nature — in a fantastic story, that made all the difference in the world. In the book, I take Dante’s story and graft my own story onto it, and in so doing hope to inspire the reader to see his or her own life story, and struggles, in light of Dante’s adventure in the afterlife.

If you want a book that explores the literary qualities of the Commedia, mine is not a book for you. This is a book that shows you how to use the Commedia to achieve what the poet himself said he wanted his masterpiece to achieve: to bring the reader from a state of despair to a state of bliss.

If you want a book that explores the literary qualities of the Commedia, mine is not a book for you. This is a book that shows you how to use the Commedia to achieve what the poet himself said he wanted his masterpiece to achieve: to bring the reader from a state of despair to a state of bliss.

There is no better time than Lent to read How Dante Can Save Your Life. You do not have to be Catholic, nor you do not have to have read the Commedia to get into the book. It is written for people who know the Commedia, and for people who have never cracked its covers. Dante’s Commedia, written in the early 14th century, is one of the greatest works ever produced by Western civilization. T.S. Eliot said, “Dante and Shakespeare divide the world between them. There is no third.”

I never studied Dante in school, and you know, I’m glad of it, because I was able to first encounter him not as a Great Man Of Literature, and his poem as a cultural Mount Everest that I was too daunted to climb. I met him in a dark wood, when he came to me as an emissary from heaven, and said, “You are lost. I know the way out. Trust me — and follow me.” That’s what How Dante Can Save Your Life is about: introducing readers to the guide who can take them out of the darkness and into the light, because in his own life, he walked that treacherous path back to God, and wrote his poem to rescue others the way God rescued him. It’s a good book for Lent, and I hope you’ll give it a try.

Plus, the design of this book — man, it’s a real art object. Look at this endpaper below. I still can’t get over that a book so beautifully designed has my name on it:

January 30, 2016

Hey Louisiana, What’s For Dinner?

January 29, 2016

Trump Plucked The Populist Apple

Take a look at the 2005 Political Typology report by the Pew Center. Note well that this came out over a decade ago. That is, before the economic crash of 2007-08, and before disillusionment with the Iraq War and the Bush administration had taken hold.

Here are the relevant takeaways:

A total of 46 percent of registered voters — Republicans and Republican-leaning independent — had in 2005 a political profile that fits with the Trump brand.

Those Pew defined as “Social Conservatives” were 13 percent of all voters in 2005. Pew defined them as: “While supportive of an assertive foreign policy, this group is somewhat more religious than are Enterprisers. In policy terms, they break from the Enterprisers in their cynical views of business, modest support for environmental and other regulation, and strong anti-immigrant sentiment.”

Only 10 percent of registered right-of-center voters — Enterprisers, the most conservative Republicans — had a 2005 profile that would reject Trump utterly.

Those Pew defined as “Conservative Democrats” — that is, social and religious conservatives who are the New Deal types, and who almost entirely lean Democratic — comprised in 2005 fifteen percent of the electorate. Pew described them this way: “Older women and blacks make up a sizeable proportion of this group (27% and 30%, respectively). Somewhat less educated and poorer than the nation overall. Allegiance to the Democratic party is quite strong (51% describe themselves as “strong” Democrats) but fully 85% describe themselves as either conservative or moderate ideologically.”

The “Partisan Poor” are the most financially disadvantaged of all the typologies, and vote heavily Democratic. A third of them are black, and they favor government services but are skeptical of government, and hostile to business interests. They were at the time 10 percent of registered voters.

So, consider this: A Republican candidate back then that could have pulled just half of the “Conservative Democrats” and half of the “Partisan Poor” would have had a working voting coalition of nearly 60 percent. He could have afforded to have lost some of the Independent and Social Conservatives to a Democrat, and still been in a strong position.

Consider this too: in both the GOP and Democratic cases, the party elites were more aligned with the most extreme on their own sides. Among the Republicans, the strongly pro-business conservatives were only 11 percent of registered voters, and a distinct minority among Republicans and Republican-leaning voters.

But they called the shots.

And they still called the shots after the 2007-08 crash.

Point is, 11 years ago, the basis for a Trump-like candidacy was there. A candidate that was broadly socially conservative, favored government programs but was broadly skeptical of government, and broadly wary of big business: that was where the great center of American politics was.

Nobody could really take advantage of it. The parties were too ideologically rigid, and redistricting favored the most ideologically rigid candidates.

In 2011, Pew had rejiggered its typological categories, and found that surprising numbers of conservatives — even in the hardest core — were a lot more skeptical of Wall Street and its relationship to the economy.

Then, in 2014, Pew released its first overall typology survey since 2005. Pew found that politics on the Right had come down to a struggle between “Steadfast Conservatives” and “Business Conservatives.” Here’s how the two conflict:

First, Steadfast Conservatives take very conservative views on key social issues like homosexuality and immigration, while Business Conservatives are less conservative – if not actually progressive – on these issues. Nearly three-quarters of Steadfast Conservatives (74%) believe that homosexuality should be discouraged by society. Among Business Conservatives, just 31% think homosexuality should be discouraged; 58% believe it should be accepted.

Business Conservatives have generally positive attitudes toward immigrants and 72% favor a “path to citizenship” for those in the U.S. illegally, if they meet certain conditions. Steadfast Conservatives are more critical of immigrants; 50% support a path to citizenship, the lowest share of any typology group.

Second, just as Steadfast Conservatives are opposed to big government, they also are skeptical of big business. They believe that large corporations have too much power, and nearly half (48%) say the economic system unfairly favors powerful interests. By contrast, as their name suggests, Business Conservatives are far more positive about the free market, and overwhelmingly regard business – and Wall Street – positively.

Finally, these two conservative groups differ over foreign policy. Steadfast Conservatives have doubts about U.S. international engagement – and view free trade agreements as a bad thing for the U.S. – while Business Conservatives are more supportive of the U.S. taking an active role in world affairs and free trade.

The Steadfast Conservatives (15% of the overall electorate) are much more likely than the Business Conservatives (12% overall) to back Trump, it would appear. But if you look further into the typology, you’ll find the single largest group, at 16%, is the Faith and Family Left — basically, pro-government, skeptical of business, but also religiously conservative. (Though I am a social and religious conservative and registered Independent who usually votes GOP, I took the Pew typology quiz, and was assigned to the Faith and Family Left.) It’s easy to see how a Trump figure could peel away some of the Faith and Family Left, as well as two of the middle groups, Young Outsiders and (especially) Hard-Pressed Skeptics.

If you look at the passage above comparing Business Conservatives to Steadfast Conservatives, which of the two sounds more like it’s represented by the Republican Party establishment?

Are you beginning to see where Trump came from?

And are you beginning to see why the gatekeepers on the GOP side — the party insiders, the think tanks, the conservative media — were able to keep any candidate who might have appealed to the middle, against the interests of Business Conservatives, from getting through?

Until along came someone so rich he didn’t have to depend on party donors and insiders to promote his political career. Those voters were there, but there was no way for Republican politicians within the system to speak to them, and for them. (And by the way, the Democrats, by having demonized so many religious and social conservatives, have the same problem.)

Here’s a link to a very important three-part series on Real Clear Politics, written by Sean Trende, on the Trump phenomenon. Excerpts from Part I, on how Trump is a very different kind of Republican, one whose appeal upsets the apple cart:

In fact, Trump’s support has largely been spread across the party, with substantial strength among moderate and liberal Republicans. … So the attempts to attack him for his lack of conservative bona fides have been ineffective because they were largely directed at voters who were not likely to vote for Trump in the first place.

But Part II of Trende’s analysis notes that Trump is also doing well with “downscale, blue-collar whites” who usually vote Democratic. The most interesting part of his essay is Part III, in which he talked about the meaning of the divide between “Cultural Cosmopolitans” and “Traditionalists”. Trende writes:

I think the outcome of this is that neither side is capable of seeing America as it actually is, and both sides believe they are far stronger than they actually are. Cultural traditionalists don’t know many gay marriage supporters (much less anyone who refers to “Caitlin Jenner”), are flummoxed as to how it could have become the law of the land, and are convinced that it must be the result of some giant lawless action. Theirs is a world turned upside down.

Cultural cosmopolitans, on the other hand, forget everything they learned in college about social desirability bias when they view polls rapidly swinging their way (with some notable exceptions), mistakenly see their victories as largely total (people online are always surprised when I point out that a near majority of Americans consider themselves Young Earth Creationists), assume that their discussions about diversity at the Oscars or transgender rights resonate with almost all Americans, and have recently moved to purge an increasing number of opposing views from the bounds of acceptable discourse, again, without a full understanding of just how many people they are silencing.

In fact, I think many cultural cosmopolitans, and again, I largely place myself in these ranks, don’t recognize these beliefs for the purely ideological statements that they are (evolution aside). The cultural cosmopolitans have an advantage in that they occupy the commanding heights of American culture, but the democratization of cyberspace and the freedom that comes with 2,000 channels on television have weakened their influence and have probably only further inflamed tensions between the groups.

Here’s the money graf:

Where this becomes relevant – indeed, I think this is crucial – is that the leadership of the Republican Party and the old conservative movement is, itself, culturally cosmopolitan. I doubt if many top Republican consultants interact with many Young Earth Creationists on a regular basis. Many quietly cheered the Supreme Court’s gay marriage decisions. Most of them live in blue megapolises, most come from middle-class families and attended elite institutions, and a great many of them roll their eyes at the various cultural excesses of “the base.” There is, in other words, a court/country divide among Republicans.

And look:

We’re left with an odd situation in which neither party’s leadership is particularly well attuned to the most important divide in American life. Democrats are openly suspicious, if not hostile, to these voters, while Republicans at best hold their noses on cultural issues if it advantages them (but they will go to the mattresses for unpopular tax cuts for wealthy Americans).

So the Republicans offer up candidates who are from cosmopolitan America, who have their speeches written by speechwriters from cosmopolitan American, who have their images created by consultants from cosmopolitan America, and who develop their issue positions in office buildings located in cosmopolitan America. Then they wonder why the base isn’t excited. Say what you will about George W. Bush, but a large part of why he was successful was that he didn’t talk like your average D.C. denizen. He was routinely mocked by the press and his own party derided his malapropisms, but he connected with a class of voters that Republicans sure could use these days, in a way that Willard Mitt Romney never could hope to (and without resorting to the demagoguery of Trump).

I read this and thought about last night’s GOP debate, and how programmed all those candidates sounded. Nobody sounds like Trump — and Trende says that this is one particular thing that the entire establishment class has missed: the way Trump talks, and why that resonates with people. Look:

Cosmopolitan America sees a strong, moral – frankly ideological – interest in accepting refugees from Syria. Traditionalist America thinks that after Paris, this is insane. Which candidate is unafraid to say this unambiguously, without feeling the need to offer caveats? Traditionalist America thinks that the nation that put a man on the moon can “control its borders”; cosmopolitan America at best offers lip service to the need for doing so. Again, how many of the surviving Republican candidates fully side with the traditionalists? Traditionalist America wants to “kick the tires and light the fires” against ISIS/Daesh, and Trump goes on Blutarsky-ish rants against them. Trump doesn’t do nuance on these issues, but the cosmopolitan Republican candidates feel the need to. (Suggest raising taxes on the wealthy, however, and all nuance goes out the window with the rest of them).

All of this is a lengthy way of saying that Trump is a creation of the Republican establishment, which is frankly uncomfortable with many of its own voters, and which mostly seeks to “manage” them. This is a group that looked at the Tea Party revolts of the past decade, looked at the broad field of Republican candidates (many of whom at least had ties to successful Tea Party revolts), and decided that none of these candidates were good enough.

Read the entire essay. It’s very insightful, and if you click that link, you’ll find embedded links to Parts I and II, though Part III is the best.

Trende calls this a “dangerous” situation, and says the Democrats have similar problems of their own. It’s dangerous because it’s destabilizing, and can easily empower a demagogue like Trump.

What Trump has shown, and is showing every day, is how out of touch Conservatism, Inc., is with the people for whom it purports to speak. They haven’t had a chance to vote for someone like him in a long, long time because, as I’ve said, the GOP and Conservatism, Inc., gatekeepers kept them down. The conservative Christians who have gone to Washington and gotten invited to be in the inner Republican power circles? You think those professional Christians really speak for the people back home anymore?

Me, I’m in a weird and extremely unrepresentative place, politically and ideologically. I am mostly a cosmopolitan in my tastes, but I live by choice in deep Red America, and am a traditionalist by conviction. What Sean Trende says about the Republican and conservative elites living inside a cosmopolitan bubble is true — and the people who give money to the GOP and to the think-tank archipelago are Business Conservatives who, as we now know post-Indiana RFRA, regard we traditionalists are the problem.

It is very useful to get this learned. For that, we can thank Donald Trump.

Look, I believe that Donald Trump is basically a pagan. I believe that Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio, who are his chief rivals now, are sincere, prayerful Christians. But I also am entirely convicted that a President Cruz or a President Rubio would, in the end, do exactly what Big Business wanted, and screw the Christians — not because they have anything against Christians, but because they know who calls the shots in the GOP. Remember what the late David Kuo told us?

This is a culture war, all right, but the battle lines have shifted dramatically. I’ll give the last word to Trende, a co-author of the 2014 Almanac of American Politics. Trump may not be the Republican nominee, and he may not be elected president. But business-as-usual with our parties is going to result in an American Caesar. Says Trende:

[I]f the parties don’t remember whom it is they serve, sooner or later that is the direction we will head.

Rome, Reformation, & Right Now

I thought the Republican debate last night went better than expected, absent Donald Trump sucking all the air out of the room. It didn’t make me like any of the candidates any better, but it felt more like a real debate than these events have been. I did come away with these thoughts:

What a shame that Rand Paul hasn’t done better in this campaign.

Alan Keyes + Jeff Spicoli + 2 Demerols + 1 Jack & Coke = Dr. Ben Carson

Chris Christie will make an excellent Attorney General in the next GOP administration

Ted Cruz is cold, dark, calculating, intelligent, ideological to the fingertips — and therefore very troubling. I cannot shake the image of him trolling suffering Middle Eastern Christians for the sake of boosting his appeal to Evangelicals. I see him and an insult Churchill directed to a rival comes to mind: “He would make a drum out of the skin of his mother to sing his own praises.”

Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio have learned nothing from Iraq. Nothing. All this talk about how under the leadership, the US is going to go in and bite the heads off of ISIS and suck their brains out, etc. — all of that requires going back to war in the Middle East. Is that really what they are proposing? If so, let’s hear the rationale. And Cruz’s line about how he’s going to carpet bomb the Mideast to rid it of ISIS — really? You’re going to wipe out tens of thousands of innocent people for this cause? Cruz’s lines attempting to link ISIS’s success to the material decline of the US military was outrageous — as if ISIS succeeded because the US wasn’t spending enough money on defense. But it tells us that a Cruz administration will mean a windfall for defense contractors.

Cruz saying that he was going to be the Second Coming of Reagan, and was going to cut taxes and get the economy moving again, so all boats can rise. It is eternally 1980 with these ideologues. They have no answer at all for our economy.

I believe Rubio said that in his overarching plan, we would work with Sunnis in the region to construct some sort of stable, post-ISIS political entity, and we would train anti-ISIS Syrians to fight the radicals. What world has Marco Rubio been living in? Did he not see that the US spent $500 million trying to train those anti-ISIS Syrians, and we only found four of them? Has Rubio not seen how well our attempts at state-building have gone in Iraq?

Maybe Donald Trump hurt himself after all by not showing up. I guess the caucuses will tell us. What last night’s event told me, though, is that with Cruz and Rubio, we pretty much get the same old GOP stuff, just a different election cycle.

Let’s turn to David Brooks’s column today, which focuses on a speech that the Tory Prime Minister David Cameron recently gave, about the future of Britain. In it, Cameron said (or Brooks implies that he said) that the usual Left-Right solution to this kind of thing — wealth redistribution downwards, or cutting taxes to free up the market so all boats can rise — no longer work. From his column:

Cameron called for a more social approach. He believes government can play a role in rebuilding social capital and in healing some of the traumas fueled by scarcity and family breakdown.

He laid out a broad agenda: Strengthen family bonds with shared parental leave and a tax code that rewards marriage. Widen opportunities for free marital counseling. Speed up the adoption process. Create a voucher program for parenting classes. Expand the Troubled Families program by 400,000 slots. This program spends 4,000 pounds (about $5,700) per family over three years and uses family coaches to help heal the most disrupted households.

Cameron would also create “character modules” for schools, so that there are intentional programs that teach resilience, curiosity, honesty and service. He would expand the National Citizen Service so that by 2021 60 percent of the nation’s 16-year-olds are performing national service, and meeting others from across society. He wants to create a program to recruit 25,000 mentors to work with young teenagers.

To address concentrated poverty, he would replace or revamp 100 public housing projects across the country. He would invest big sums in mental health programs and create a social impact fund to unlock millions for new drug and alcohol treatment.

It’s an agenda that covers the entire life cycle, aiming to give people the strength and social resources to stand on their own. In the U.S. we could use exactly this sort of agenda. There is an epidemic of isolation, addiction and trauma.

Read the whole thing. Brooks goes on to say that the GOP desperately needs to take this “Burkean” approach to repairing the social fabric. I think he’s right, but I also think that is not remotely adequate to the problem we face. The State can help economically, but it simply cannot do the work of culture.

The State cannot make people stop having babies out of wedlock. The State cannot make people stay married. The State cannot reweave family bonds. The State cannot make people believe in God, and order their lives accordingly. And so forth. This is not to say that there is no role for the State, of course, only that its ability to help is largely at the margins. That’s not nothing — but it’s not nearly enough.

I’ve been reading this week historian Brad Gregory’s study The Unintended Reformation: How A Religious Revolution Secularized Society. I had imagined it to be a somewhat polemical book that blamed the Reformation for all our modern woes. That was dumb of me. It’s a genealogy of ideas and events that led to our current condition.

It didn’t start with the Reformation. The ideas that laid the intellectual groundwork for the Reformation sprung out of Catholic theological debate two centuries earlier. The corruption of the Catholic Church, and the arrogant refusal of its leaders to heed calls to reform before it was too late, were very real and present. Luther had reason. He had the intellectual framework in place, and he had emotional cause: the utter rot within the Roman Catholic establishment.

That doesn’t make the Reformation right, of course, but one does see how it was all but inevitable. Once the break happened, it proved impossible to contain the forces unleashed. “Sola scriptura” proved an impossible standard for building a new church, because various Reformation leaders had their own ideas about what the Bible “clearly” said. The fracturing of the Reformation, and the arguments among various theological factions, were there from the beginning.

And the savagery with which Catholics and Protestants went at each other was horrifying. The Wars of Religion were catastrophic, and in Gregory’s telling, compelled exhausted Europeans to try to figure out a way to keep the peace. This required a strong state that kept religious passions in check. At the same time, the rise of science, and the blind obstinacy of the Roman church in unnecessarily holding on to Aristotelian categories for understanding the natural world, created the false belief that religion is opposed to science. And on and on, through the Enlightenment, down to the present day.

There’s a lot more to it than I’ve said here. It’s a very complex story, and certainly not one with a straight-line cause, e.g., “If not for nominalism and univocity, none of this would have happened;” “If not for the Reformation, none of this would have happened.” The point I wish to make here is that Gregory does a great job in showing how the interaction of ideas, events, and plain human folly, served to drive God out of the public square. He also makes it clear that the secular liberal narrative of uncomplicated Progress because of this is hopelessly naive. The Enlightenment tried to build a binding public ethic around Reason, but ran into the same problem that the Reformation did: who decides what counts as “reasonable”? As Gregory writes:

‘Sola ratio’ has not overcome the problem that stemmed from ‘sola scriptura,’ but rather replicated it in a secular, rationalist register. Attempts to salvage modern philosophy by claiming that it is concerned with asking questions rather than either finding or getting closer to finding answers might make sense – if one just happens to like asking questions in the same way that thirsty people just like seeking water rather than locating a drinking fountain, or indeed having any idea whether they are getting closer to one.

The point of this post — and of Gregory’s book — is certainly not to blame the Reformers. What good would that do, anyway? Nor is it to say, “The Renaissance Popes made us do it!” Again, that is pointless now. The thing to learn from this study is how ideas have consequences — and not just ideas, but ideas as they are taken up by real people in particular circumstances.

Gregory’s book makes very clear that the Reformers would have been horrified by what became of their revolution, just as the Franciscan friars Duns Scotus and William of Ockham would likely have been appalled by what their ideas — univocity and nominalism — brought about. They all meant well. One has much less sympathy for the leaders of the Roman church, who sat back enriching themselves while the faith for which they were responsible fell into radical discredit by their own corruption. Had they foreseen where all this would lead, they surely would have repented before it was too late.

Or not. As Kierkegaard says, the trouble with life is it must be lived forward, but can only be understood backwards.

The unwinding we’re all seeing now is the cumulative effect of forces that have been gathering for a very long time. We are living through the failure of liberalism (in the classical, 19th century sense) because we have become incapable of stable self-government. We are coming apart because there is no center around which we can all rally. John Adams famously wrote

[W]e have no government armed with power capable of contending with human passions unbridled by morality and religion. Avarice, ambition, revenge, or gallantry would break the strongest cords of our Constitution as a whale goes through a net. Our Constitution was made only for a moral and religious people. It is wholly inadequate to the government of any other.

It is wishful thinking to believe that Christianity can, at this point, stop the forces of disintegration and dissolution moving through American society and culture. Christianity can hardly protect itself from the same (Moralistic Therapeutic Deism with a nominally Christian face predominates). We are living through, and will continue to live through, the political consequences of Christianity’s demise as the guiding vision of our society, and its replacement with radical individualism. I point you to this 1989 essay in The Atlantic by political scientist Glenn Tinder, who wrote of the political meaning of Christianity. Excerpts:

It will be my purpose in this essay to try to connect the severed realms of the spiritual and the political. In view of the fervent secularism of many Americans today, some will assume this to be the opening salvo of a fundamentalist attack on “pluralism.” Ironically, as I will argue, many of the undoubted virtues of pluralism—respect for the individual and a belief in the essential equality of all human beings, to cite just two—have strong roots in the union of the spiritual and the political achieved in the vision of Christianity. The question that secularists have to answer is whether these values can survive without these particular roots. In short, can we be good without God? Can we affirm the dignity and equality of individual persons—values we ordinarily regard as secular—without giving them transcendental backing? Today these values are honored more in the breach than in the observance; Manhattan Island alone, with its extremes of sybaritic wealth on the one hand and Calcuttan poverty on the other, is testimony to how little equality really counts for in contemporary America. To renew these indispensable values, I shall argue, we must rediscover their primal spiritual grounds.

… The most adamant opposition to my argument is likely to come from protagonists of secular reason—a cause represented preeminently by the Enlightenment. Locke and Jefferson, it will be asserted, not Jesus and Paul, created our moral universe. Here I cannot be as disarming as I hope I was in the paragraph above, for underlying my argument is the conviction that Enlightenment rationalism is not nearly so constructive as is often supposed. Granted, it has sometimes played a constructive role. It has translated certain Christian values into secular terms and, in an age becoming increasingly secular, has given them political force. It is doubtful, however, that it could have created those values or that it can provide them with adequate metaphysical foundations. Hence if Christianity declines and dies in coming decades, our moral universe and also the relatively humane political universe that it supports will be in peril. But I recognize that if secular rationalism is far more dependent on Christianity than its protagonists realize, the converse also is in some sense true. The Enlightenment carried into action political ideals that Christians, in contravention of their own basic faith, often shamefully neglected or denied. Further, when I acknowledged that there are respectable grounds for disagreeing with my argument, I had secular rationalism particularly in mind. The foundations of political decency are an issue I wish to raise, not settle.

More:

If the denial of the God-man has destructive logical implications, it also has dangerous emotional consequences. Dostoevsky wrote that a person “cannot live without worshipping something.” Anyone who denies God must worship an idol—which is not necessarily a wooden or metal figure. In our time we have seen ideologies, groups, and leaders receive divine honors. People proud of their critical and discerning spirit have rejected Christ and bowed down before Hitler, Stalin, Mao, or some other secular savior.

When disrespect for individuals is combined with political idolatry, the results can be atrocious. Both the logical and the emotional foundations of political decency are destroyed. Equality becomes nonsensical and breaks down under attack from one or another human god. Consider Lenin: as a Marxist, and like Marx an exponent of equality, under the pressures of revolution he denied equality in principle—except as an ultimate goal- and so systematically nullified it in practice as to become the founder of modern totalitarianism. When equality falls, universality is likely also to fall. Nationalism or some other form of collective pride becomes virulent, and war unrestrained. Liberty, too, is likely to vanish; it becomes a heavy personal and social burden when no God justifies and sanctifies the individual in spite of all personal deficiencies and failures.

The idealism of the man-god does not, of course, bring as an immediate and obvious consequence a collapse into unrestrained nihilism. We all know many people who do not believe in God and yet are decent and admirable. Western societies, as highly secularized as they are, retain many humane features. Not even tacitly has our sole governing maxim become the one Dostoevsky thought was bound to follow the denial of the God-man: “Everything is permitted.”

This may be, however, because customs and habits formed during Christian ages keep people from professing and acting on such a maxim even though it would be logical for them to do so. If that is the case, our position is precarious, for good customs and habits need spiritual grounds, and if those are lacking, they will gradually, or perhaps suddenly in some crisis, crumble.

And:

To what extent are we now living on moral savings accumulated over many centuries but no longer being replenished? To what extent are those savings already severely depleted? Again and again we are told by advertisers, counselors, and other purveyors of popular wisdom that we have a right to buy the things we want and to live as we please. We should be prudent and farsighted, perhaps (although even those modest virtues are not greatly emphasized), but we are subject ultimately to no standard but self-interest. If nihilism is most obvious in the lives of wanton destroyers like Hitler, it is nevertheless present also in the lives of people who live purely as pleasure and convenience dictate.

And aside from intentions, there is a question concerning consequences. Even idealists whose good intentions for the human race are pure and strong are still vulnerable to fate because of the pride that causes them to act ambitiously and recklessly in history. Initiating chains of unforeseen and destructive consequences, they are often overwhelmed by results drastically at variance with their humane intentions. Modern revolutionaries have willed liberty and equality for everyone, not the terror and despotism they have actually created. Social reformers in the United States were never aiming at the great federal bureaucracy or at the pervasive dedication to entertainment and pleasure that characterizes the welfare state they brought into existence. There must always be a gap between intentions and results, but for those who forget that they are finite and morally flawed the gap may become a chasm. Not only Christians but almost everyone today feels the fear that we live under the sway of forces that we have set in motion—perhaps in the very process of industrialization, perhaps only at certain stages of that process, as in the creation of nuclear power—and that threaten our lives and are beyond our control.

There is much room for argument about these matters. But there is no greater error in the modern mind than the assumption that the God-man can be repudiated with impunity. The man-god may take his place and become the author of deeds wholly unintended and the victim of terrors starkly in contrast with the benign intentions lying at their source. The irony of sin is in this way reproduced in the irony of idealism: exalting human beings in their supposed virtues and powers, idealism undermines them. Exciting fervent expectations, it leads toward despair.

And then read Damon Linker’s essay today about the political meaning of Donald Trump. He begins by discussing how democracies need mediating institutions to work. And those mediating institutions must have the confidence of leaders and the led. The system requires people to trust their institutions. Linker:

As this week’s events have demonstrated, the [political] gatekeeping process only works if the candidates accept Fox’s legitimacy to serve in that role [as a media gatekeeper for what is legitimate to say on the Right]. With his prodigious use of Twitter, remarkable capacity to generate publicity for himself in more traditional media outlets, and willingness to make strident demands and stick to them, Donald Trump is testing the power of this institution like no one before him. When the Republican candidate leading in every national and most state polls not only refuses to participate in a debate hosted by the most powerful media outlet on the right but actually organizes a competing event designed to undermine the legitimacy of the official debate, that’s an act of outright insubordination against the prevailing political norms and institutions of civil society.

It’s also an act that exposes how little formal power such norms and institutions ever really possess. They gain their force solely from our collective willingness to abide by them. As Rush Limbaugh pointed out in a surprisingly insightful rant on his radio show earlier this week, the system only works because when Fox says, “come take part in this debate,” the candidates respond, “Yes, please!” All it takes for the system to break down is for the frontrunner to walk away, ignore (or attack) the gatekeeper, and use other media outlets to go over its head to speak directly to the voters, circumventing (and badly undercutting) the institution in the process.

This, Linker goes on to say, is why the rise of Trump means the decay of democracy into “darker forms of government.”

He’s right about that, but with Brad Gregory’s book in mind, if Trump is a Luther figure, it’s important to keep in mind how the institutions of American life have failed, giving rise to him. Michael Brendan Dougherty says, of Trump voters: