Rod Dreher's Blog, page 617

February 3, 2016

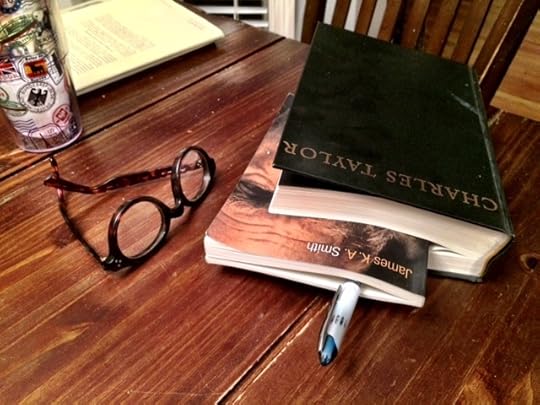

‘Mom, I Think We Have Peak Dad’

“Mom, I think we have Peak Dad,” said my son Matthew, spying the scene above, where I had been working. Too true. I’m very deep down the Benedict Option book research rabbit hole.

Fun With Fly Vomit & E. Coli

My late father was a state health inspector in his first career. That made life around our house interesting. I’ll never forget him fussing at us kids one day for not covering up food left out on the counter, thereby leaving it vulnerable to house flies.

“Do you know what a fly does when he lands on food?” he said. “He vomits on it. They showed us a training film with a close-up of a fly puking on a slice of lemon meringue pie.”

Turns out that’s not really true — flies don’t vomit, but they do drool — but it was close enough to freak us out, and make us shape up. Over four decades later, I cannot look at lemon meringue pie without thinking of upchucking houseflies. Yeah, it was fun having a health inspector for a dad.

I bet it’s much tougher having as your father Bill Marler, who is arguably the No. 1 food safety lawyer in the country. In a recent piece, he listed the six foods his experience has taught him never to eat. Among them:

3. Meat that isn’t well-done. Marler orders his burgers well-done. “The reason ground products are more problematic and need to be cooked more thoroughly is that any bacteria that’s on the surface of the meat can be ground inside of it,” Marler says. “If it’s not cooked thoroughly to 160°F throughout, it can cause poisoning by E. coli and salmonella and other bacterial illnesses.” As for steaks, needle tenderizing—a common restaurant practice in which the steak is pierced with needles or sliced with knives to break down the muscle fibers and make it more tender—can also transfer bugs from the surface to the interior of the meat. If a restaurant does this (Marler asks), he orders his steak well-done. If the restaurant doesn’t, he’ll opt for medium-well.

And:

6. Raw oysters and other raw shellfish. Marler says that raw shellfish—especially oysters—have been causing more foodborne illness lately. He links this to warming waters, which produce more microbial growth. “Oysters are filter feeders, so they pick up everything that’s in the water,” he explains. “If there’s bacteria in the water it’ll get into their system, and if you eat it you could have trouble. I’ve seen a lot more of that over the last five years than I saw in the last 20 years. It’s simply not worth the risk.”

I cited those two because I love my steaks medium-rare, and like my burgers pink inside. And of course I absolutely adore raw oysters. I confess, though, that I eat a lot fewer Louisiana oysters than I have in the past, simply because our waters here are warmer.

In a really interesting follow-up interview with the Washington Post, Marler told a stunning anecdote:

Do you know the juice Odwalla? Well, the juice is made by a company in California, which has made all sorts of other juices, many of which have been unpasteurized, because it’s more natural. Anyway, they were kind of like Chipotle, in the sense that they had this aura of good and earthy and healthful. And they were growing very quickly. And they had an outbreak. It killed a kid in Colorado, and sickened dozens of others very seriously, and the company was very nearly brought to its knees. [The outbreak, which was linked to apple juice produced by Odwalla, happened twenty years ago].

If you look at how they handled the PR stuff, most PR people would say well, they handled it great. They took responsibility, they were upfront and honest about it, etc etc. What’s interesting though is that behind the scenes, on the legal side of the equation, I had gotten a phone call, which by itself isn’t uncommon. In these high profile cases, people tend to call me—former employees, former government officials, family members of people who have fallen ill, or unknown people giving me tips. But this one was different. It was a Saturday—I remember it well—and someone left me a voicemail telling me to make sure I get the U.S. Army documents regarding Odwalla. I was like ‘what the heck, what the heck are they talking about?’ So I decided to follow up on it, and reached out to the Army and got something like 100 pages of documents. Well, it turned out that the Army had been solicited to put Odwalla juice on Army PX’s, which sell goods, and, because of that, the Army had gone to do an inspection of a plant, looked around and wrote out a report. And heres what’s nuts: it had concluded that Odwalla’s juice was not fit for human consumption.

Wow.

It’s crazy, right? The Army had decided that Odwalla’s juice wasn’t fit for human consumption, and Odwalla knew this, and yet kept selling it anyway. When I got that document, it was pretty incredible. But then after the outbreak, we got to look at Odwalla’s documents, which included emails, and there were discussions amongst people at the company, months before the outbreak, about whether they should do end product testing—which is finished product testing—to see whether they had pathogens in their product, and the decision was made to not test, because if they tested there would be a body of data. One of my favorite emails said something like “once you create a body of data, it’s subpoenable.”

So, basically, they decided to protect themselves instead of their consumers?

Yes, essentially. Look, there are a lot of sad stories in my line of work. I’ve been in ICUs, where parents have had to pull the plug on their child. Someone commented on my article about the six things I don’t eat, saying that I must be some kind of freak, but when you see a child die from eating an undercooked hamburger, it does change your view of hamburgers. It just does. I am a lawyer, but I’m also a human.

Readers, have you ever had serious food poisoning? If so, did it affect the way you eat? I can think of only one time I had it bad, and that was when both my wife and I got very sick on Christmas Day from undercooked chicken we had eaten the night before. Salmonella, I guess. It was unreal, the misery. Since then, we have been a lot more careful about how we cook chicken. You don’t forget something like that.

Whistling Past The Graveyard

I can’t understand the rationale — aside from wish fulfillment — for so many pundit types writing Donald Trump off and extolling Marco Rubio after the Iowa result.

Yes, it was a disappointing showing for Trump, considering the high expectations he had raised prior to the caucus. Still, he came in second place in a state where he had no ground game (versus Ted Cruz, who had an amazing one), a state where ground game is of paramount importance. Rubio’s third place showing was impressive, and launched him into position to be the consensus Establishment candidate that the party and movement elites have been hoping for.

But consider that Trump is massively ahead in New Hampshire — 21 points ahead of his nearest rival, Cruz (who is barely ahead of Rubio and Kasich). Unlike Iowa, New Hampshire, which votes Tuesday, is a primary state, which is not going to hurt Trump as much as the caucus system did. There hasn’t been a South Carolina poll since the Iowa result, but the last one had Trump up by over 16 points. South Carolina votes February 20, and Nevada, where Trump is also far ahead, caucuses on February 23.

After that is Super Tuesday, March 1, when a lot of Southern states vote. Trump is running strong in the South now.

Look, a lot can change in the next three weeks. But if Trump wins decisively in NH, and then in SC, he will have tremendous momentum going into Super Tuesday. If he loses SC, Trump will look a lot more vulnerable than he does post-Iowa. Still, I understand GOP regulars being relieved that Rubio has a shot, but do they really think that all the things that made grassroots conservatives embrace Donald Trump are going to evaporate overnight?

As for Ted Cruz, he can count on winning his home state of Texas on Super Tuesday, which is huge. But remember, conservative Evangelicals are his base, and he’s going to have to show that he can appeal beyond them. Iowa Republicans are heavily Evangelical (as 2008 Iowa winner Mike Huckabee and 2012 Iowa winner Rick Santorum can testify), but that’s less true in most other places.

I still find it hard to imagine Donald Trump as the Republican nominee, but I’ve been wrong about him for a long time. This pundit rush-to-Rubio seems awfully premature, is what I’m saying.

A Work of Restoration

I focus a lot on Gloom, Despair, and Agony On Us (hat tip: Hee-Haw), so it’s a pleasure to post this e-mail from a reader:

I don’t know if I’ve told you about our parish school that has rebooted itself much in the model of St. Jerome’s. Anthony Esolen wrote about it here:

http://www.crisismagazine.com/2015/a-parish-school-turns-failure-into-success

I think it would be worth sharing it with your readers. (I am biased but also want people to know about it.)

My son went to Montessori preschool there last year and we moved all my school age kids there this year. It has been AWESOME! We had been sending our kids to the local public schools because the other Catholics schools in the area didn’t inspire much. They seemed like glorified public schools with a dollop of religion. (Indeed, they seem to run after what the public schools are doing. I almost drove off the road when I heard a Catholic high school talk about the bold move it had made by bringing new technology into the classroom for every single student. This was what he thought boldness in Catholic education was.)

In many ways the local public schools match up with our desires to live in a walkable community. My sixth grader would have had a two-block walk to school. My third grader would have been in the same school he and his sister were in last year which is about 10 minute walk. But there are no ideal situations in this world.

The straw that broke the camel’s back was my daughter being about to move to the middle school. It is the same school I went to and like most middle schools it has a Lord of the Flies atmosphere. But that wasn’t the deal breaker. Rather, it was the “optional” use of Chromebooks by all the students. And we are talking about the liberal sort of option that is basically mandatory because all the classes teach to the laptops and the classrooms have ONE set of textbooks per class that a student can check out.

We knew the classical model was better, but we also had some big sacrifices to make. Besides, there is something Catholic to being rooted in place. We tried to sell our house but were not successful, and so we have a 15-minute drive every morning — which is minimal compared to some other families; our friends in DC roll their eyes at because they’d die for such a short school commute.

We are six months in and we are so incredibly happy. To have teachers pulling in the same direction, to have your kids start each day with the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, to be able to sit with them at daily Mass when I can, has been awesome. And the things they are learning are the things I am still trying to catch up on! My kids were sledding with their uncle (my brother-in-law) and he asked my sixth grader what she was reading. She proceeded to tell him about the allegory of the cave from Plato’s Republic which they had been reading and discussing. I didn’t read any of that–probably didn’t even know about it–until college. They are learning Latin and being challenged in their religion. For instance, the wonderful religion teacher that my daughter has challenged them to make the case for Christ’s divinity but then had them flip around and prosecute the other side and make the arguments for why he wasn’t divine. He wants them to think these things through, not simply to recite some lines from the Catechism.

One of the keys is the smallness of the place. Another key has been our pastor’s willingness to reach out to homeschoolers. So often parish schools are antagonistic towards homeschoolers. Our school has something called the Classical Enrichment Curriculum (CEC) that allows homeschoolers to take classes a la carte on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Some homeschoolers have ended up switching to full time but others continue to come twice a week.

The headmaster is a not someone from the educational bureaucracy; he’s a Air Force colonel and a lawyer and so he thinks outside the box.

I am blabbering but I really have been blown away by what is going on in this school. My sixth grader also isn’t fighting a constant battle each day in school. She’s not being made fun of because she doesn’t have the latest iPhone. She is able to be sheltered in a good way.

The liturgical life is so rich too. Our kids had Mass on the Ephiphany in the Extraordinary Form. Yesterday, they had a beautiful Candlemas celebration. They have Adoration every Tuesday and the kids spend time there as classes. They have regular confessions.

Here’s the website about the school: http://sacredheartacademygr.org/

Here are some youtube videos about the academy and the parish:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2ySy7iuu1NM

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bwsTzGBbmss

Pictures from Candelmas: https://www.facebook.com/DanielBennettPage/posts/10153380872151699

Pictures from a Rorate Mass in December (scroll down): http://www.newliturgicalmovement.org/2015/12/advent-photopost-rorate-masses.html#.VrJFT9IrKM8

Again, I am going on and on, but it gives me so much joy to have this place and to see it growing. There are families moving to be closer. There are families driving an hour to bring their kids here. There is something special happening. I’d love it if you could share some of this!

With pleasure. Reading this, I am reminded of how Cardinal Newman described the work of the early Benedictines:

St Benedict found the world, physical and social, in ruins, and his mission was to restore it in the way not of science, but of nature, not as if setting about to do it [the caveat], not professing to do it by any set time, or by any rare specific, or by any series of strokes, but so quietly, patiently, gradually, that often till the work was done, it was not known to be doing. It was a restoration rather than a visitation, correction or conversion. The new work which he helped to create was a growth rather than a structure. Silent men were observed about the country, or discovered in the forest, digging, clearing and building; and other silent men, not seen, were sitting in the cold cloister, tiring their eyes and keeping their attention on the stretch, while they painfully copied and recopied the manuscripts which they had saved. There was no one who contended or cried out, or drew attention to what was going on, but by degrees the woody swamp became a hermitage, a religious house, a farm, an abbey, a village, a seminary, a school of learning and a city.

If you know who John Senior was, it will not surprise you to learn that this school, Sacred Heart Academy, is, in a way, the fruit of his labor. The Sacred Heart provost was mentored by Hillsdale College’s David Whalen, who in this lecture talks about his experience with the legendary Kansas professor — a proto-Benedict Option-er if ever there was one.

Male And Female He Did Not Create Them

St. Chrysostom’s, a progressive parish in the not-at-all-declining Church of England, is hosting “The Gospel According to Jesus Queen of Heaven,” a play written by and starring Jo Clifford, a male-to-female transsexual. The play imagines Jesus as a transsexual returning to earth in the present day. According to the orthodox Anglican blog Stand Firm in Faith, the local Anglican bishop has said nothing about this blasphemy. Watch the reimagined “Our Father” by Jo Clifford above, if you want a better idea about what the Anglicans at St. Chrysostom, and the Bishop of Manchester, support.

It used to be: “Heather has two mommies.”

Now, it’s: “Heather has two non-gendered and inclusive caregivers.”

That’s the language the New Democratic Party government in Alberta, Canada, is telling teachers and school administrators to use when adressing the adults with whom students are living. Out: “mother” and “father.” In: “parent,” “caregiver,” “partner,” whatever.

And God help you if refer to one of the little rascals as “him” or “her.”

Here’s the pertinent language from the rainbow-adorned “Guidelines for Best Practices” that the highminded-progressive NDP government issued last week:

School forms, websites, letters, and other communications use non-gendered and inclusive language (e.g., parents/guardians, caregivers, families, partners, “student” or “their” instead of Mr., Ms., Mrs., mother, father, him, her, etc.).”

The purpose of the guidelines, according to the text, is to create “learning communities” that “respect diverse sexual orientations, gender identies, and gender expressions.”

And that means that the kids, no matter how young or how old, get to pick their own gender and force everyone else in the school to abide by their choice.

It should be up to each individual whether they use a washroom designated for males or females, according to the guidelines.

Specifically, the document states that students should be “able to access washrooms that are congruent with their gender identity.” …

As much as possible, the guidelines call for the elimination of separate activities for students based on gender.

[Education Minister Dave] Eggen said discussions with school boards will continue and there will soon be meetings with Catholic Church leaders as well.

“Certainly I knew this wasn’t going to be easy, but important things are never necessarily easy to achieve,” Eggen told The Canadian Press Thursday.

“We’ll receive different opinions on this, but I always take it back to first principles, which is to protect and to focus on children, especially young vulnerable children in regards to gender identities. Once we do remind ourselves of those things, then it becomes clearer what has to be done,” he said.

Won’t somebody please think of the children! As usual, the propagandistic shibboleth of “safety” is invoked to steamroller the rights of the Church and Catholic parents to run their own schools according to their own beliefs. Americans, say it again and again: “Thank you, Almighty God, for the First Amendment.” There is no doubt in my mind that if not for the First Amendment, gay activists and their institutional supporters would eventually force these policies on religious schools in the US too.

Back in the UK, a private school for kids aged 11-18 is celebrating diversity by allowing students to claim whatever gender category they like. The Archbishop Cranmer blog comments:

Of course, God loves His creation, and, of course, that includes (without exception) the spectrum of hormonal beings who, whether by nature or nurture, are ‘fluid’ in their sexuality, or ‘non-binary’ in their identity. But in these schools, God (and/or nature) seems to have become subordinate to ‘welfare’ and ‘happiness’, which is defined not in terms of any transcendental or altruistic pursuit, but in purely selfish terms of sexual self-identity. Happiness is not to be found in personal sacrifice, selflessness, moral virtue or seeking the beatific truths of God: it is found in the hedonistic attainment of personal pleasure and natural desire, which resides most supremely in contemplating and then realising the act of sexual union with whomever, whenever and however one pleases.

We might leave autonomous, mature adults to decide these ethical matters for themselves: it is not for the Christian to impose his conception of holiness or orthodox morality upon the unbelieving world. But schoolchildren? Are they not to be taught to distinguish left and right (moral neutrality) from right and wrong (moral responsibility)? If they are to be taught that God’s goodness and their happiness consists in the self-contained indulgence of assertions of gender self-identity, then we are not only ordering the natural world of biology to suit the political agenda of a tiny minority, but redefining what it means to be humanly fulfilled and ultimately ‘happy’.

Steadily, the very essence of what it means to be male, female, and even human, is being destroyed. Nothing but chaos and will. You know exactly where this is going.

UPDATE: Charles Taylor, in A Secular Age, speaks to what is so dishonest about the way we frame this discussion, in a passage criticizing the way certain concepts are deployed rhetorically to shut down discussion. For example, he says that there are a number of reasons why abortion should be legal, but “choice” is not one of them. In fact, “this kind of appeal trivializes the issue.” More:

[Choice] is a word which occludes almost everything important: the sacrificed alternatives in a dilemmatic situation, and the real moral weight of the situation.

And yet we find these words surfacing again and again, slogan terms like “freedom”, “rights”, “respect”, “non-discrimination”, and so on. Of course, none of these is empty in the way “choice” is; but they too are often deployed as argument-stopping universals, without any consideration of the where and how of their application to the case at hand.

We are watching the concept of fundamental categories like male and female dismantled before our eyes, with no debate about it, without consideration of what this might mean for present and future generations. It all gets pushed along under the concept of “safety” or “diversity,” or some other benign term used in an Orwellian way. As Taylor notes about how oversimplification makes it easier to overpower your opponents (“Four legs good, two legs bad!”), “Shallowness and dominance are two sides of the same coin.”

The Architecture of the Benedict Option

One question in particular is less commonly discussed, and it is this: is there any way to make use of the physical fabric of Christian England to increase the resilience of Christian communities? This question occurred to me when reading the US writer Rod Dreher, who has for several years been writing about something called the “Benedict Option”. This is an umbrella term he coined for the many and varied ways in which he argues that Christian communities can and must develop spiritual and cultural resilience in response to the challenges of living in heavily secularised and anti-religious countries, at a time when government, business and culture are profoundly hostile to traditional religious beliefs and practices.

More:

There seems too to be a link between building and ritual. One of the themes in Dreher’s Benedict Option writing is his belief that churches that do not have formal liturgy and traditional, structured devotional practices will face an extra barrier in maintaining their integrity and vitality as Christian congregations when persecution comes or when their members face the harsh winds of cultural ridicule and disapproval. Liturgies and traditional practices act as an anchor to the tradition of the Church, they remind congregations of their adherence to the Creeds and that they are part of something much greater which should not be lightly rejected or tampered with. Solidity, routine and sacraments help to build strong Christians. Ancient church buildings can be a hugely important component of this grounding of the faith. Their physicality is a reminder that the faith is not some kind of gnostic spiritualised thing, but is closely concerned with the material creation, with the lives of people who have bodies.

This brings to mind the last time I was in Cambridge, and stopped into St. Bene’t’s (that is, Benedict’s), which dates to the 11th century and is the oldest building in the town. I spent some time praying there, and was nearly overwhelmed by the fact of that church: that Christians have been praying on that spot for nearly a thousand years. That those stones have absorbed the prayers, the chants, and the hymns of worshipers for a millennium. What an incredible gift the people of Britain, and indeed of Europe, have in their ecclesial architectural heritage.

Follow Niall Gooch @epiphaniall, by the way. He’s always got something good to say. And by the way, if you have not yet read the recent First Things essay about building, harmony, and God by architect Christopher Alexander, make amends right this very second!

A New Kind of Catholic School?

A reader writes:

The story about your friends pulling their kids out of Catholic school hit particularly close to home as my wife and I have reached a breaking point with our parish school. Our seven year old daughter has had nearly the identical experience as your friends’ 10 year old. We are very orthodox, but it seems

like most of the school families are cultural comformists, or as a previous commenter indicated more MTD than Catholic. I know most of these kids are being exposed to the full range of bile which our popular culture spews. Our 7 year old daughter has not yet made her first communion, but already she has had a male classmate give a note telling her, “I like your ass,” and has overheard a male classmate telling the girls in the class that he played naked with a girl in his neighborhood. This is concerning enough although I would guess this 7 year old boy doesn’t understand what he’s saying.

More disturbing is the garbage that has come home from the school library where ostensibly there should be some adult oversight as to what the kids can take out or

what should be in a Catholic school library to begin with. We’ve not seen anything like the book you mentioned in your earlier post, but we’ve seen books that glorify all manner of disrespectful behavior, bathroom humor, bullying, mocking people including teachers for weight, hairstyle, dress, etc. Our children are no longer allowed to check books out of the school library because we simply cannot trust the staff to provide appropriate guidance.

There is another factor at work with many Catholic

Schools that has not been mentioned and that is the simple fact that so many of them, ours included, are struggling just to survive. They’re struggling to survive because so many Catholic parents, the vast majority at our middle class suburban parish, send their kids to public schools. Our school is so desperate to increase enrollment that they water down the faith to attract anyone who might be looking for an alternative to public schools of uneven quality. We just had our annual Catholic Schools week open house this weekend, and my wife overheard perhaps the very best and most devout teachers on the faculty, someone who is extremely active in the parish and whom we know to be very committed to her faith tell a prospective, non-Catholic parent that while the school is Catholic it’s not, “overly Catholic.” I cannot tell you how dispiriting this is especially since I’m far from certain that the principal and other teachers are as devout as this teacher.

We are fortunate that in our area there is a private, non parochial Catholic school, recognized by the archdiocese, but not part of the deeply bureaucratic archdiocesan system. This school was founded about 15 years ago by a group of well-to-do Catholics who were not satisfied with the orthodoxy of the local parochial schools. We’ve been doing our due diligence on this school, but all the evidence indicates that it is exactly what we’re looking for. When I first started researching it, I was quickly struck by the impression that it’s the Benedict Option in practice. And it’s more academically rigorous as well. It costs quite a bit more, but it will be more than worth it if it’s what it appears to be. Even so, I know that in our culture, the cost of my children’s innocence and their souls is eternal vigilance.

I was talking not long ago with a friend and reader of this blog who was telling me about the Catholic school system in his very Catholic hometown. It is a lot like the reader above describes his daughter’s school, and my friend said that there are a fair number of Catholic parents who would love to take their kids out of the diocesan system and put them into a Catholic school that took the faith seriously. But there are none.

My friend has what I think is a great idea, following on the example of St. Jerome’s in Hyattsville, Md., profiled in the Washington Post. Why not take one of the failing Catholic schools in the local diocesan system and remake it as a “classical” school? Protestants are way ahead on the classical model, and Catholics have a lot to learn from them — and from fellow Catholics like the folks at St. Jerome’s. From the WaPo piece:

“Classical” education aims to include instruction on the virtues and a love of truth, goodness and beauty in ordinary lesson plans. Students learn the arts, sciences and literature starting with classical Greek and Roman sources. Wisdom and input from ancient church fathers, Renaissance theologians and even Mozart — whose music is sometimes piped into the classrooms to help students concentrate better — is worked in.

On the hallway walls outside Clayton’s classroom are student posters on the theme “What is goodness?,” “rules for knights and ladies of the Round Table,” drawings of Egyptian pyramids, directions to “follow Jesus’ teachings” and “be respectful toward others,” and other exhortations to live a noble life.

“The classical vision is about introducing our students to the true, the good, the beautiful,” Principal Mary Pat Donoghue points out. “So what’s on our walls are classical works of art. You won’t see Snoopy here.”

Classical theory divides childhood development into three stages known as the trivium: grammar, logic and rhetoric. During the “grammar” years (kindergarten through fourth grade), children soak up knowledge. They memorize, absorb facts, learn the rules of phonics and spelling, recite poetry, and study plants, animals, basic math and other topics. Moral lessons are included.

And:

“We defined what we meant by ‘classical’ in very Catholic terms,” says Michael Hanby, a committee member and a professor at the John Paul II Institute at Catholic University. “It was not just a method but an incorporation into the whole treasure of Christian wisdom, which includes that of Christian cultures. Our students would get a coherent understanding of history, literature, art, philosophy — the traditions to what Catholics in the West are heirs.”

It could be kind of a “magnet school” for Catholic parents who want something richer and deeper for their children than the “Catholic lite” approach that frustrates many parents. And it need not be outside of the diocesan system.

What’s not to like? Tell me, Catholic readers, especially you Catholic school teachers.

February 2, 2016

As The Worm Turns

.@roddreher The sexual revisionists are starting earlier than this! In the lib in my conservative, rural locale: https://t.co/iJXOmEFibT

— Christopher Jackson (@revcjackson) February 2, 2016

The Kirkus review of this book:

Austrian and Curato turn the simple wedding of two worms into a three-ring circus that slyly turns the whole controversy over same-sex versus heterosexual marriage on its head.

“Worm loves Worm. ‘Let’s be married,’ says Worm to Worm. ‘Yes!’ answers Worm. ‘Let’s be married.’ ” Seems simple to the two worms but not to the other woodland critters. Cricket insists on officiating. “That’s how it’s always been done” is his oft-repeated refrain. Beetle wants to be the best beetle, the Bees want to be the bride’s bees, the worms must wear rings, and they need a band to dance to, flowers, and a cake. The intendeds solve all these issues as well as the question of who’s the bride, who’s the groom. “ ‘I can be the bride,’ says Worm. ‘I can, too,’ says Worm.” They both are also the groom. One wears a veil, bow tie, gold ring, and black trousers; the other sports a top hat, gold ring, and flouncy white skirt. The wedding party is in awe, save uptight Cricket. “ ‘We’ll just change how it’s done,’ says Worm.” And so they do, and they are married at last…“because Worm loves Worm.” Curato’s pencil-and-Photoshop illustrations use white backgrounds to great effect, keeping the characters front and center. The two worms are differentiated only by their eyes: one has black dots, and the other has white around the black dots.

As in life, love conquers all

From the Publishers Weekly’s review:

How do you explain a revolution to a young audience? This book is a terrific start. … Then their friends make one more demand: there can only be one bride and one groom: that’s “how it’s always been done.” And that’s when the worms show they have a spine. “We can be both,” they insist, mixing and matching veils, tuxes, dresses, and top hats. “We’ll just change how it’s done.” Debut author Austrian proves that it’s possible to be silly and incisive at the same time, while Curato (the Little Elliot books) works in a stripped-down style that subtly reinforces the “all you need is love” message.

According to the image provided by the Tweeter, this new book is now on the shelves at the public library in rural Algoma, Wisconsin (pop. 3,167).

Liquid Parenting

Writing on the smartphones-as-hand-grenades thread, “Teen Love In The Ruins” thread, reader Irenist said:

What troubles me most here is the commenters on this very thread who seem to think it’s laughable to want to prevent teens from having pre-marital sex, and who take umbrage at being told that it is “barbaric” not to object to such fornication.

First, not all teens have sex. If 70% of 19 year olds have had sex, then 30% haven’t. And so forth for whatever the numbers are. So as a factual matter, it is in fact possible for temptation to be resisted.

Second, the entire Western world until very, very recently would have held that it was simply obvious that civilized people ought to object to the sort of thing Rod says the book is about. We have gone from “of course fornication is wrong, even if it happens” to “of course teen pre-marital sex is healthy and it’s going to happen anyway” in a VERY short time, historically.

What worries me isn’t smut like this book: that has indeed been around for ages. What worries me is that my version of the BenOp does NOT involve running off to some Catholic commune somewhere, but instead trying to live among neighbors of many faiths and none. And what this thread is telling me is that if I want my children not to sleep around as teens, that secular and liberal parents, if they hear that, will scoff at me for being unrealistic, and take umbrage at my presumed judgmentalism toward their more laissez faire attitudes. Worse, they will happily let their kids sleep with my kids under their own roof. What this thread indicates is that liberals and secularists are not my allies in trying to keep my kids chaste, but instead enemies who will happily subvert my supposedly outmoded attitudes. And that’s a lot more worrisome for a parent surrounded by liberal, secular parents than any silly YA novel. A lot more.

I have met the problem, and it is you guys.

This is true, but it’s not the whole truth. I was just on the phone talking to a friend who lives in another state. He and his wife have decided to homeschool their children next year. They are taking their kids out of Catholic school. Among the reasons? One of their daughters, age 10, has been socially isolated by her friends there. The girls told this kid — whom I’ve met, and who is the most vivacious, gregarious little girl — that because she doesn’t watch the same TV shows as they do (e.g., “Modern Family”) and listen to the same pop music that they do, that they can’t be friends with her. For the last three weeks, his daughter has been eating lunch at school alone, reading a book.

This is not the only reason they’re bailing on Catholic school. But it does seem to have been a last straw.

Now, do you suppose the parents who send their kids to this Catholic school are secular liberals? I very much doubt it. What they are is conformists. They are more afraid of telling their kids “no,” and of their kids not being popular, than anything else. My friend and his wife put their kids in Catholic school in part to form them in a community of faith. But that community is a façade. The children within it come from homes where they are exposed to the same garbage as everybody else’s kids are.

I completely agree with Irenist that “liberal, secular” parents of our kids’ friends are a problem when they actively or passively subvert traditional Christian virtue, e.g., by letting kids who come over watch something sexually explicit. But “conservative, religious” parents are scarcely better when they have the same “whatever” stance towards popular culture, social media, and so forth as everybody else, but think somehow that, magically, holding the correct opinions about God, cultural politics, and the like will protect their kids.

It is astonishing how quickly this has passed. When I was a kid, it was easy to count on the moms and dads of your kids’ friends to hold particular lines on what was acceptable and unacceptable in terms of behavior, cultural consumption, and everything else. Of course there were far fewer opportunities to be transgressive, but most parents believed that the lines were pretty clear, and worth defending. About 15 years ago, I was talking to a group of New York City police detectives for a project I was working on, and listened with fascination as all of them recalled their childhoods in the 1960s, in which their parents relied on the same thing. It was the parents’ code.

It’s all gone. And if you think it’s only gone among secular liberal parents, you’d better wake up. There is no solidarity parenting anymore. It’s all liquid now, as in Zygmunt Bauman’s concept of “liquid modernity”:

[I]ts characteristics are about the individual, namely increasing feelings of uncertainty and the privatization of ambivalence. It is a kind of chaotic continuation of modernity, where a person can shift from one social position to another in a fluid manner. Nomadism becomes a general trait of the ‘liquid modern’ man as he flows through his own life like a tourist, changing places, jobs, spouses, values and sometimes more—such as political or sexual orientation—excluding himself from traditional networks of support.

Bauman stressed the new burden of responsibility that fluid modernism placed on the individual—traditional patterns would be replaced by self-chosen ones.

The responsibility of parenting has become much more difficult with the collapse of the code of parental solidarity. One way of coping with the pressure is pretending that this is not actually a problem at all, that everything is going to be fine if we just do what everybody else is doing, and hope for the best.

We want to be sure. We want to be able to count on each other, as parents. But how do we do it? We are all treading water in the liquid.

The most difficult part of the Benedict Option project will be convincing people that you cannot live this way, not if you want your kids to hold on to the faith, or even moral sanity. In the age of liquid parenting, every family is an island.

UPDATE: Here is a comment by James C., on the smartphones thread. It applies here too, so I’m going to share it with you:

People are complacent and lackadaisical about it until it happens to them. And it will.

My niece doesn’t have a smart phone, but other kids at school do. She uses my sister’s smart phone from time to time to play games.

Well, last year we discovered her looking at hardcore pornography on it. She was barely 7 years old.

Who taught her to do that? Other parents’ kids, of course. And when my sister put a search filter on the phone, she still was able to do searches to view some pretty risqué stuff. Afraid some other kids would teach her how to get around the filters, my sister banned the phone. Period. How important is a smartphone? Enough to risk poisoning your kid’s mind and destroying his/her innocence? I don’t think so.

Smartphones As Hand Grenades

Petula Dvorak, writing in the Washington Post, comments on the horrifying tale of the 13-year-old Virginia girl who left home to meet someone she met on a dating app, and whose body was subsequently found. Two Virginia Tech students are in custody in connection with the murder. Dvorak:

Police told Nicole’s mom, Tammy Weeks, that they think the sweet-faced girl met Eisenhauer online.

The details of that are still unclear, but here’s what we know for sure: Nicole led an active, imaginary life online, meeting people on Kik, a messaging app that has been the bane of law enforcement officials for the past couple of years.

The app grants users anonymity, it allows searches by age and lets users send photos that aren’t stored on phones.

It’s popular with tweens and teens — and predators.

“Unfortunately, we see it every day,” said Lt. James Bacon, head of the Fairfax County Police Department’s child exploitation unit.

Every day. More:

This shadow world may be where Eisenhauer met Nicole, police told her mother. “It was some off-the-wall site I never heard of,” Weeks said in an interview with The Washington Post.

In the digital age, any parent can be Tammy Weeks. Smartphones have made it easier to keep tabs on our children — and much, much harder.

Teens have been outmaneuvering their mothers and fathers for decades. Back in my day, we told our parents we were spending the night at Melanie’s house when we were really at the Echo and the Bunnymen show an hour away, Ferris Buellering our way through adolescence.

But a lot of times, our parents won, because they caught us sneaking out. Or they called Melanie’s mom.

This world? The predators aren’t just hiding behind the Galaga machine at the arcade. They’re in our kids’ pockets, in their backpacks, in their bedrooms.

Whole thing here. Dvorak says “it’s not okay to play the Luddite.” Oh? Why not? How have we managed to convince ourselves that our children need smartphones? It’s a lie. You know what it is? Parents don’t want to go against the flow. Every other parent is letting their kids have smartphones, and parents don’t want to be thought poorly of by their kids or the other parents. It really is hard to tell your kids “no” about this stuff, and to keep telling them no, every damn day. Believe me, I know this firsthand. I’m no model parent in this regard. But I’ll tell you this: our younger kids do not have smartphones, and will not have them, even though a lot of kids their age — 9 and 12 — have them. You can install things to protect your kids, and you should. But I cannot see any good reason why a child that young should have a smartphone.

Some dear friends are going through hell right now because of some social media mess their adolescent got mixed up in. It scares the crap out of me, to be honest. Everybody thinks it won’t happen to them. But it can, and it does. A lawyer friend, a mom, was telling me not long ago that she tried to show a relative of hers who lets his young kids have smartphones how easy it is for them to google extremely harmful content online. It did no good. Me, I think people like me, well-meaning parents, live in denial, telling ourselves that our kids aren’t going to misuse their smartphones, because we find it too hard to say no to them. (The same is true with television too, by the way.)

I don’t have the time or the skills to monitor everything my kids would get into on their smartphones, if they had them, and access to social media. But you know what? Why should I. They are nine and 12 years old. They have no business with smartphones, Instagram accounts, Facebook, Snapchat, and all the rest. They are not ready for those things. I certainly would not have been at that age. You give your kids a smartphone with access to the Internet and social media, you are handing them grenades.

It is hard as hell to be a countercultural parent. But what else is there?

UPDATE: I made a funny mistake here — read “Petula Dvorak” and wrote it as “Petula Clark.” Thanks to the reader who corrected me.

UPDATE.2: Reader B. Minich writes:

To be fair, what the author seems to mean by “it’s not OK to play the Luddite” seems to be more aimed at the baffling attitude some parents have that they’ll just let their kids have this technology they don’t understand, and all will be fine!

After all, not long afterwards, she encourages parents to be like the dad who took his daughter’s phone away, and stuck to his guns when charged with a crime for it. (Which is INSANE, btw.)

Though the story doesn’t seem to even address the idea of holding off on giving your kids smartphones, just knowing what’s happening and restricting them somewhat. So it does still fall short a bit.

I think this is fair, and I apologize for misreading Dvorak. Still, as you say, the assumption seems to be that the pressure to give your kid a smartphone is irresistible. When did we as a culture decide this? Yes, I am more than a little panicked about this, because I’m watching my poor friends go through something just short of catastrophic, and it all blew up so quickly.

UPDATE.3: James C. writes:

People are complacent and lackadaisical about it until it happens to them. And it will.

My niece doesn’t have a smart phone, but other kids at school do. She uses my sister’s smart phone from time to time to play games.

Well, last year we discovered her looking at hardcore pornography on it. She was barely 7 years old.

Who taught her to do that? Other parents’ kids, of course. And when my sister put a search filter on the phone, she still was able to do searches to view some pretty risqué stuff. Afraid some other kids would teach her how to get around the filters, my sister banned the phone. Period. How important is a smartphone? Enough to risk poisoning your kid’s mind and destroying his/her innocence? I don’t think so.

UPDATE.4: Reader Andrea, who is a professional journalist, writes:

I have spent the past eight months covering court cases and reading graphic and disturbing criminal affidavits, some about cases like these. After that, I would advise any parent I knew to strictly monitor their child’s phone and Internet use. If they don’t know how, it’s time to learn. Even more importantly, they should know where their teenagers are at and what they’re doing. It amazes me how many 12 to 14-year-olds are unsupervised and getting into trouble (late at night) that their parents apparently either didn’t care about or didn’t make an effort to prevent.

If I had kids, they would not have smart phones until they were in the late teens. If they did, I’d make sure they had a very detailed and graphic course ahead of time in the potential hazards and in how easily they could be charged with a crime for sexting or uploading photos of themselves, etc. I worry about what my 9-year-old nephew might have seen online.

UPDATE.5: I don’t want to leave the impression that I’m some model of perfection on this. I certainly am not! I’m thinking now of ways that I, as a father, fall short. I am thinking of ways that I tell myself everything is fine, that I don’t need to monitor this or that, that I should just trust because … I am too lazy and distracted to verify. I accuse myself of this, because it’s true. Just wanted to get that out there.

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 509 followers