Rod Dreher's Blog, page 622

January 20, 2016

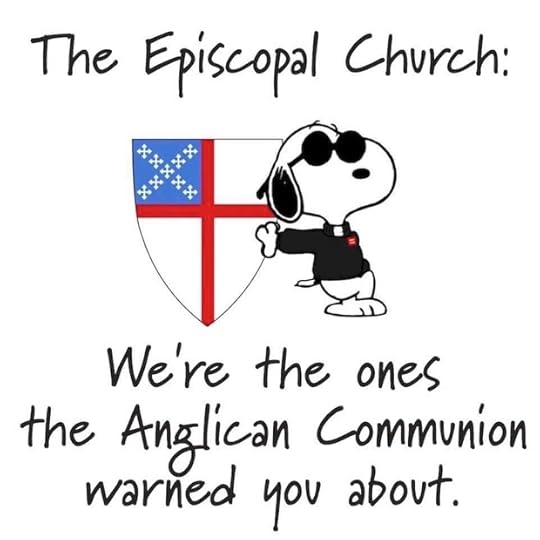

Bad-Boy Episcopalians

This meme has been going around in my networks since the Anglican Communion put the Episcopal Church on a three-year suspension for its liberal policies on homosexuality.

The punitive measures and conservative statement came after four days of “painful” talks in Canterbury aimed at moving the world’s 85 million-strong Anglican fellowship beyond deep divisions over homosexuality between liberals and conservatives.

An agreement, published on Thursday evening, said the US Episcopal church’s acceptance of same-sex marriage represented “a fundamental departure from the faith and teaching held by the majority of our provinces on the doctrine of marriage”.

In a passage that dismayed liberal Anglicans, the agreement explicitly added: “The traditional doctrine of the church in view of the teaching of scripture, upholds marriage as between a man and a woman in faithful, lifelong union. The majority of those gathered reaffirm this teaching.”

Under the agreement, the US Episcopal church has been banned from representation on key bodies and barred from voting on issues relating to doctrine or strategy for three years. However, it will remain a member of the Anglican communion.

The Presiding Bishop of TEC says that there’s no going back from its pro-gay position. I don’t see how it avoids being thrown out of the Anglican Communion three years from now. But we’ll see.

There’s been a lot of playing the “Martyr For Compassion” among liberal Episcopalians since last week’s act by the Anglican Communion. This is not surprising. Still, it can’t be a good sign that people in a church that has been nearly severed from its historic communion are treating this as a Joe Cool moment. It’s startlingly trite and trivializing. But it may not be entirely unreasonable.

Here’s an interesting report from TEC itself, on where its growth is happening, and why. Overall the church is shrinking, and shrinking dramatically. Only a minority of its parishes are growing at all, and those are primarily in the South and the West, which are more religiously conservative than the Northeast and Midwest, the other two regions surveyed. However, the particular parishes that are growing are, by a large margin, the progressive ones.

This suggests to me that the Episcopal brand has become so identified with liberal Christianity that its only place to grow is among religiously inclined progressives. Most of the conservatives who can’t go along with this have already left. On current trends, TEC is on track to reduce itself to a tiny progressive core. For reasons of theological consistency (with its past actions), and marketing to a shrinking audience, defying the global Anglican Communion and embracing a Joe Cool stance makes some sense. I guess. But contemplate, if you will, an America in which to be a member of The Episcopal Church is to make oneself part of the left-wing vanguard.

Law School Marginalizes Haters

A reader who practices law in Louisville, Kentucky, e-mails with a story of the Law of Merited Impossibility manifesting at the University of Louisville’s Brandeis School of Law.

The other day, Luke Milligan, a law professor there, wrote an op-ed in the local newspaper decrying the way the school is becoming ideologized. Excerpts:

Since 1846 the law school at the University of Louisville has provided nonpartisan space for individuals to teach, discuss, and research matters of law and public policy. Despite the thousands of partisans who’ve walked its halls, the law school as an institution has remained nonpartisan, preserving its neutrality, and refusing to embrace an ideological or political identity.

Unfortunately, this long run of institutional neutrality seems headed for an abrupt end. Promotional materials for the law school now proclaim its institutional commitment to “progressive values” and “social justice.” Incoming students and faculty are told that, when it comes to the big issues of the day, the law school takes the “progressive” side.

The plan, in short, is to give the state-funded law school an “ideological brand.” (The Interim dean says it will help fundraising and student recruitment.) In 2014, the law faculty voted — over strong objection — to commit the institution to “social justice.” Now we’re at it again, seeking to brand ourselves “the nation’s first compassionate law school.”

A liberal law professor shot back:

Nevertheless, I found myself not only surprised, but deeply disappointed and frankly embarrassed that my colleague, Professor Luke Milligan, wrote a misleading opinion column in this space on Jan. 13, objecting to the proposal to have the Brandeis School of Law partner with the city, and many of our leading corporate and civic institutions, as part of the Compassionate Louisville campaign.

The views Professor Milligan expressed completely misrepresented both the nature of the Compassionate Louisville campaign and the law school’s commitment to it.The premise of Professor Milligan’s polemic was that identifying the law school as a compassionate institution is somehow a “partisan” stance that takes sides in ideological wars in which he believes a law school should not take sides. I’m sure that community leaders such as Brown-Forman, Metro United Way, Spalding University, YMCA of Greater Louisville, Norton Healthcare, Guardiacare, KentuckyOne Health, Sacred Heart Academy, Yum! Brands, the University of Louisville Medical School, and dozens more will be quite surprised to learn that by partnering with the Compassionate Louisville initiative, they have all taken sides in the culture wars or been somehow partisan.

Equally surprised, we must assume, are the hundreds of cities across the nation (including such bastions of liberal orthodoxy as Fayetteville, Huntsville, Dallas, Tulsa, and Winston-Salem) that have also become Compassionate Communities, only to learn that they are also part of this partisan, ideological plot to impose compassion. But according to Professor Milligan, that’s just what they’ve all done.

This is an astonishingly sad way to look at the world – and especially to see the notion of compassion, as being the exclusive preserve of one ideology. I do not believe it ever occurred to anyone who proposed this at the law school or voted for it that it had any ideological or partisan content at all, or that supporting it somehow sent a message that a commitment to compassion would, could or should exclude anyone based on party or ideology.

A third professor said no, the law school really is pushing leftism:

There is ample evidence that the law school has veered to a partisan agenda. In a prior commentary, I discussed the diversity training conducted by the law school in collaboration with the Vice President for Diversity. At those events, faculty, staff and students were instructed to identify their religious beliefs, sexual orientation and disabilities, and attendees were ordered to clap enthusiastically (it was made quite clear that silence or even polite clapping was simply not acceptable).

Even more troubling, Professor Milligan is absolutely correct about the fact that a leftist agenda affects the classroom environment at the Brandeis School of Law. Deeply troubled by the liberal branding of the law school, and the adoption of the “social justice” mandate, a colleague had the temerity to make the following statement to his students on the final day of class last semester:

“Don’t let people here—students or faculty—pressure you to compromise your political, legal, social, or religious views. Many of our graduates look back and regret having been sheepish in expressing and developing their political views when they were at this law school. Conservative views have an equal place alongside liberal views at the Brandeis School of Law. I don’t care what the Dean says. I don’t care what your Con Law professors say. And on this point, neither should you. This is your education—not the Dean’s, not the faculty’s. Develop your political and legal views freely while you’re here. Take care. Good luck on the exam.”

What extraordinary ideas! Students should be encouraged to think for themselves. Not everyone need blindly adhere to the faculty’s (or the dean’s) liberal values.

Given the current repressive climate at the law school, perhaps the colleague should have anticipated a negative reaction to his statement. However, I doubt that he could have remotely imagined what actually happened. When the interim dean found out about the statement, she did not adopt a strong pro-free speech stance, or emphasize the importance of free speech and the exploration of ideas in a university environment. Nor did she, as one might also have expected, speak to the faculty member in order to ascertain the facts.

Heaven forbid that she follow Justice Brandeis’ admonition that “knowledge is essential to understanding and understanding should precede judging!” Instead, that very day, she marched over to complaint with university officials regarding the statement, and she then sent the faculty member an e-mail ordering him to schedule an appointment with the officials.

Well, yesterday, the law school faculty voted overwhelmingly to join the “compassion” campaign. From the newspaper report:

Professor Sam Marcosson, who defended the resolution in an online commentary, said that faculty considered adding respect for ideological diversity in the resolution but found no dictionary that defined compassion as including that.

“It is about empathy for the pain and suffering of others,” he said.

Oh, brother. More:

Professor Manning Warren, the only professor besides Weaver to speak against the resolution, described himself as a liberal Democrat but complained that compassion is “a loaded term.”

“Does it mean you feel sorry for the 16-year-old girl who is raped,” he asked, “or her unborn baby?”

“It just doesn’t make sense to vote on something when we don’t know what it means,” he said.

Well, we do know what it means: it means a left-wing social agenda. Given how Big Business stomped religious liberty in the Indiana RFRA debacle, it is risible to cite corporate support for stuff like this as evidence that it is non-partisan, or in any way conservative.

Liberals use “compassion” and “social justice” the way conservatives of another era would have used “patriotism”: as a moralistic cudgel to demonize points of view they would rather not have to hear. “Surely, professor, you love America, yes? Then how can you possibly object to ____?”

Prof. Milligan said this is where “compassion” has already led:

We’re already experiencing the fallout at the law school. In the name of “social justice” and “compassion,” students were instructed on Day 1 of law school to rise and make public declarations regarding their race, religion, and sexual orientation. Under the Interim dean’s gaze, new students came out as gay, the devoutly religious were told to cheer for atheism, and evangelicals were called on to applaud the LGBT community.

State-sponsored “compassion” and “social justice” left students wondering if they’d need to sacrifice personal privacy, political values, and deeply held religious convictions in order to succeed at law school.

Imagine being compelled on the first day of law school in 1957 to stand and make public declarations of your politics, your patriotism, and your view on communism. How welcome do you think dissenters from “100% Americanism” would have fared? How do you think law students asked in those days to declare their Judaism or their atheism would have felt that day?

For the SJWs on faculty, in university administrations, and among the students, this is all about will to power. And note well that these lawyers, indoctrinated in “compassion,” who are going to be the judges of tomorrow.

This is how it happens. Remember, folks: “It’s not going to happen, and when it does, you people will deserve it.”

Conservatism Will Not Save Christianity

A couple of readers have sent me a column by the Catholic priest Fr. Dwight Longenecker, in which he lists Twelve Reasons Why Progressive Christianity Will Die Out. Here’s how he sets up the list:

The historic Christians believe their religion is revealed by God in the person of his Son Jesus Christ, and that the Scriptures are the primary witness of that revelation. They believe the church is the embodiment of the risen Lord Jesus in the world and that his mission to seek and to save that which is lost is still valid and vital. Historic Christians believe in the supernatural life of the Church and expect God to be at work in the world and in their lives.

Progressive Christians believe their religion is a historical accident of circumstances and people, that Jesus Christ is, at best, a divinely inspired teacher, that the Scriptures are flawed human documents influenced by paganism and that the church is a body of spiritually minded people who wish to bring peace and justice to all and make the world a better place.

I realize that I paint with broad strokes, but the essential divide is recognizable, and believers on both sides should admit that “historic” and “progressive” Christians exist within all denominations. The real divide in Christianity is no longer Protestant and Catholic, but progressive and historic.

When I say “divide” I should say “battle” because both sides are locked in an interminable and unresolvable battle. Interminable because neither side will yield and unresolvable because the divisions extend the the theological and philosophical roots of both aspects.

However, it is true to look at the dynamic of progressive Christianity and see that by the end of this century it will have either died out or ceased to be Christianity.

I agree with this, with a slight modification. Most of the progressive Christians I know would say that Jesus was (is) divine. Yet they live their theology as if he were little more than a divinely inspired teacher. It’s a distinction without a lot of difference, but I do want to acknowledge that many progressive Christians do profess Christ’s divinity.

His main point is generally true, in my experience, and so is his list. Yet the reading that I’ve been doing lately leaves me unsatisfied with it; the list is true, but only a partial truth. Indeed it makes me think that many Christians who identify with the conservatives are much more vulnerable to the same dynamics that will eliminate progressive Christianity than they realize. Let me explain.

As many of you know, I’ve been much taken with the Reformed theologian Hans Boersma’s 2011 book Heavenly Participation: The Weaving of a Sacramental Tapestry. In it, Boersma talks, in everyday, non-technical language, about the theological and philosophical basis of the first thousand years of Christianity. He calls it a “Platonic-Christian synthesis” — that is, the belief that all matter, all nature, is metaphysically anchored in God. That is, that everything that exists receives its very existence from God, and subsists mysteriously in God.

This changed radically in the High Middle Ages for a number of reasons Boersma detailed. The most significant of them were the rise of univocity and nominalism. I’m greatly simplifying here, but univocity means that God is not Being itself, but a category of Being. He sits atop the hierarchy of Being, as its supreme entity. This served to crack the metaphysical bond between God and Nature. As Boersma writes, no longer did earthly objects receive their reality from God’s own being. Rather, they possessed their own being. This effectively makes the created order independent of God.

Then came nominalism, which denies that there is an intrinsic essence in anything. Matter has meaning through an act of will. Ockham and the nominalists did not deny God’s existence, but they said that insofar as anything meant anything, it was because God willed it to be so (this, as distinct from the view that it is part of His nature, because he is in some sense united to Nature). Move God out of the picture and then man’s relationship to Nature is one in which we can do anything we want with it, bound by no natural laws. There is no natural teleology.

These and other factors at work in the West laid the groundwork for the ongoing exile of God from, well, life. (Interestingly, Boersma points out that almost all of this took place before the Reformation, though the Reformation, and the Counter Reformation, accelerated the process already underway.) In the Great Tradition, nothing existed on its own; everything was really connected in God and through God. Modernity — starting with the Late Middle Ages — progressively unraveled the “sacramental tapestry.” Boersma says that only a return to the sacramental vision of the Great Tradition can save the church today from dissolution.

He writes the book as an Evangelical Protestant theologian, primarily addressing Evangelicals, but he warns that Catholics, though retaining a more robust sacramentality, are in effect aboard the same modernist boat, headed over the falls. This is because we all live in the modern world, and modernism is powerfully anti-sacramental. We have all been formed by it; it is the water in which we fish swim. The Orthodox Church never lost the Great Tradition, but it has taken me almost a decade of being Orthodox to retrain my own way of seeing the world, to re-sacramentalize it. To see the world with the sacramental eyes of the Great Tradition requires real and sustained effort.

One of the most difficult things as a Christian to fight against is the idea that the Christian life is chiefly about studying the Bible (and, for Catholics, the Catechism) and learning through a process of rationality how to apply its teachings to govern our lives. In the Great Tradition, as Boersma shows so well, Scripture, the Church, and the doctrines that come out of them all derive their meaning from the living God, who desires radical communion with us: theosis. This is not a contractual agreement by us that God is real and His teachings are true (though we must agree to these things), but rather an ongoing absorption in His life, and a reweaving of the sacramental tapestry through His work in our own lives.

It’s a hard concept to understand, I know, and I don’t have the time or the space to go into it in more detail here. Besides, it’s more the kind of thing you have to grasp today, on the far side of the Modern era, by prayer and experience, as opposed to cogitation. Nevertheless, Boersma makes a strong case that reclaiming this Great Tradition the only thing that stands to stop and reverse the fragmentation and dissolution of the Christian faith in the West.

I believe he’s right about that. The forces dissolving our sacramental bonds to God and to each other, reducing us to individuals defined by our desires, are overwhelming. Conservative Christians are in a stronger position to resist them than progressive Christians, if only because they believe (in principle) that Truth is something outside of ourselves, to which we must conform our own lives — this, as opposed to the idea that we can rewrite the faith and redefine virtue according to our own experiences and felt needs, because the only thing that matters is that we feel a connection to an amorphous, beneficial God. But if you look at the way many of us conservative/orthodox Christians actually live, we are also headed down the river and over the falls too, just more slowly than the progressive Christians.

Here is a great passage from Boersma. He’s talking about the way we in modernity view time non-sacramentally — as the past and the future having no real connection with ourselves, because it exists separate from the eternal God:

A desacramentalized view of time tends to place the entire burden of doctrinal decision on the present moment. I, in the small moment of time allotted to me, am responsible to make the right theological (and moral) choice before God. The imposition of such a burden is so huge as to be pastorally disastrous. Furthermore, to the extent that as Christians we are captive to our secular Western culture, it is likely that this culture will get to set the church’s agenda. … The widespread assumption that Christian beliefs and moral are to a significant degree malleable has its roots in a modern, desacralized view of time.

If we forget the past, denying that we have any necessary connection to it, to tradition, we forget who we are, who we must be, and how we must live.

To the extent that today’s conservative Christians are alien to the Great Tradition, they (we) are not much better off than the progressive Christians whose dissolution in modernity we are observing, often with self-satisfaction (I’m guilty of this too).

I want to end by these passages from a great little book by the late Orthodox theologian Olivier Clément. He’s talking about the recovery of the sacramental:

The world is not a prison but a dark passage — an opening through which to move, a passage to be deciphered within a greater work. In this work, everything has a meaning, everyone is important, everyone is necessary. It is a work that we compose together with God.

… One of our daily tasks is precisely to awaken in our selves the power within the depths of our heart. Usually, we live in our heads and in our sexuality, with our hearts closed off. But only the heart can serve as the crucible in which our understanding and desire are transformed. And though we may not reach the luminous abyss, sparks may fly from it, and our hearts burn with an immense yet gentle shudder.

We must recover the meaning of this unemotional emotion, this unsentimental sentiment, this peaceful and overwhelming resonance of our whole being we feel when our eyes are filled with tears of wonder and gratitude, ontological tenderness and fulfilled silence. It is not merely the concern of monks; it is humbly and partially the concern of us all. And I would argue that it is also a concern of culture. … We need music, poems, novels, songs and any art that has the potential to be popular art and which awakens the power within our hearts.

Culture is not just art, but fasting, feasting, the way we live as a people. Anyway, Clément here states a rationale for the Benedict Option. The recovery of the Great Tradition is not merely the concern of us all.

January 19, 2016

Trump, Mad Genius

Well, I thought the Palin speech was grating and idiotic, but then, I would think that. But in terms of politics, I agree with Scott Adams: it was probably a home run for Trump.

Before Palin took the stage, my colleague Daniel Larison tweeted that Trump, who gassed on about his greatness for over 20 minutes, was saying the same things that made us all dismiss him as a joke six months ago. Who’s laughing now? You wanna laugh at this year’s model of Palin too?

She’s a much better articulator of Trumpism than Trump himself is. She’s upbeat, she’s folksy, she brings the you-betcha populism home hard. Her entire message was, “They think they’re so much smarter than us, but our Donald, he’ll show them! Come on, gang, are you with us?” She’s a much more practiced giver of speeches than Trump is, and much better at it. It doesn’t matter that people like me blanch at her whiny accent, her cheesy rhetoric, her dopey malapropisms (“squirmishes” for “skirmishes”). She killed on that stage.

David Frum says this is the triumph of right-wing identity politics:

Since Donald Trump entered the race, one opponent after another has attacked him as not a real conservative. They’ve been right, too! And the same could have been said about Sarah Palin in 2008. Palin knew little and cared less about most of the issues that excited conservative activists and media. She owed her then-sky-high poll numbers in Alaska to an increase in taxes on oil production that she used to fund a $1,200 per person one-time cash payout—a pretty radical deviation from the economic ideology of the Wall Street Journal and the American Enterprise Institute. What defined her was an identity as a “real American”—and her conviction that she was slighted and insulted and persecuted because of this identity.

That’s exactly the same feeling to which Donald Trump speaks, and which has buoyed his campaign. When he’s president, he tells voters, department stores will say “Merry Christmas” again in their advertisements. Probably most of his listeners would know, if they considered it, that the president of the United States does not determine the ad copy for Walmart and Nordstrom’s. They still appreciate the thought: He’s one of us—and he’s standing up for us against all of them—at a time when we feel weak and poor and beleaguered, and they seem more numerous, more dangerous, and more aggressive.

He continues:

Meanwhile, Trump is battling against Ted Cruz of Princeton and Harvard Law School, a Supreme Court practitioner married to an investment banker, who insists that the dividing line between “us” and “them” is not life story, not personal experience, but ideas and values.

Donald Trump, billionaire real estate tycoon, just covered himself with downmarket, populist glory tonight. And as Frum says (it’s a great short piece), if this pushes Trump over the top in Iowa, and he wins big in New Hampshire (as he is poised to do), Trump heads into South Carolina with tremendous momentum — and he’s already up 14 points over Cruz, his nearest competitor, in the Palmetto State.

Not a single vote has been cast, but already, the Republican establishment is in shambles. Not one of its candidates are truly competitive. Not yet. Maybe they never will be. If Rubio doesn’t show in Iowa, New Hampshire (his best shot), or South Carolina, the party regulars are going to go all in for the despised-by-GOP-insiders Cruz to stop Trump. Which may not even be possible by that point.

Either way, by this time next year, we will have a different Republican Party.

Hillary’s E-Mail Problem Goes Nuclear

I know we’re all having fun snorting at the Palin-Trump carnival, but this is actual news:

Hillary Clinton’s emails on her unsecured, homebrew server contained intelligence from the U.S. government’s most secretive and highly classified programs, according to an unclassified letter from a top inspector general to senior lawmakers.

Fox News exclusively obtained the unclassified letter, sent Jan. 14 from Intelligence Community Inspector General I. Charles McCullough III. It laid out the findings of a recent comprehensive review by intelligence agencies that identified “several dozen” additional classified emails — including specific intelligence known as “special access programs” (SAP).

That indicates a level of classification beyond even “top secret,” the label previously given to two emails found on her server, and brings even more scrutiny to the presidential candidate’s handling of the government’s closely held secrets.

Fox goes on:

Access to a SAP is restricted to those with a “need-to-know” because exposure of the intelligence would likely reveal the source, putting a method of intelligence collection — or a human asset — at risk.

The Clintons are jaw-droppingly reckless. Always have been, always will be. They think laws don’t apply to them. And look how David Petraeus, who did the same thing, got off with a slap on the wrist.

Did you ever read Mike Lofgren’s essay about the “Deep State”? Here’s an excerpt:

Washington is the most important node of the Deep State that has taken over America, but it is not the only one. Invisible threads of money and ambition connect the town to other nodes. One is Wall Street, which supplies the cash that keeps the political machine quiescent and operating as a diversionary marionette theater. Should the politicians forget their lines and threaten the status quo, Wall Street floods the town with cash and lawyers to help the hired hands remember their own best interests. The executives of the financial giants even have de facto criminal immunity. On March 6, 2013, testifying before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Attorney General Eric Holder stated the following: “I am concerned that the size of some of these institutions becomes so large that it does become difficult for us to prosecute them when we are hit with indications that if you do prosecute, if you do bring a criminal charge, it will have a negative impact on the national economy, perhaps even the world economy.” This, from the chief law enforcement officer of a justice system that has practically abolished the constitutional right to trial for poorer defendants charged with certain crimes. It is not too much to say that Wall Street may be the ultimate owner of the Deep State and its strategies, if for no other reason than that it has the money to reward government operatives with a second career that is lucrative beyond the dreams of avarice — certainly beyond the dreams of a salaried government employee.

The corridor between Manhattan and Washington is a well trodden highway for the personalities we have all gotten to know in the period since the massive deregulation of Wall Street: Robert Rubin, Lawrence Summers, Henry Paulson, Timothy Geithner and many others. Not all the traffic involves persons connected with the purely financial operations of the government: In 2013, General David Petraeus joined KKR (formerly Kohlberg Kravis Roberts) of 9 West 57th Street, New York, a private equity firm with $62.3 billion in assets. KKR specializes in management buyouts and leveraged finance. General Petraeus’ expertise in these areas is unclear. His ability to peddle influence, however, is a known and valued commodity. Unlike Cincinnatus, the military commanders of the Deep State do not take up the plow once they lay down the sword. Petraeus also obtained a sinecure as a non-resident senior fellow at the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard. The Ivy League is, of course, the preferred bleaching tub and charm school of the American oligarchy.

Hillary Clinton is of these people, and will be taken care of by them, even if it becomes obvious that by normal standards, she ought to be indicted. As rich and as ridiculous as Donald Trump is, he’s not one of them. Hence his appeal to people who would normally not give a showboating buffoon like him a second glance. You really do wonder how much worse for America he would be than four more years of a Deep Stater. On the other hand, as Mollie Hemingway tweeted:

There is a certain BURN IT ALL DOWN that you have to enjoy about what’s happening, but it might not be in the country’s long-term interest.

— Mollie (@MZHemingway) January 19, 2016

Lofgren’s essay, by the way, has now been turned into a book titled, helpfully enough, Deep State.

GOP Drops AcidPalin Endorses Trump

Sarah Palin, the former Alaska governor and 2008 vice-presidential nominee who became a Tea Party sensation and a favorite of grass-roots conservatives, will endorse Donald J. Trump in Iowa on Tuesday, officials with his campaign confirmed. The endorsement provides Mr. Trump with a potentially significant boost just 13 days before the state’s caucuses.

“I’m proud to endorse Donald J. Trump for president,” Ms. Palin said in a statement provided by his campaign.

Her support is the highest-profile backing for a Republican contender so far.

“I am greatly honored to receive Sarah’s endorsement,” Mr. Trump said in a statement trumpeting Mrs. Palin’s decision. “She is a friend, and a high-quality person whom I have great respect for. I am proud to have her support.”

“A high-quality person.” Does it get any Trumpier than that?

And the USS Republican Party just sailed over the horizon. Oh, but high-quality reality stars the Duck Dynasty clan have come out for Cruz, in an Internet spot that’s the cringeworthiest thing you will see until there’s video of Palin’s endorsement of Trump. So there’s that. (We generally don’t embed or link to political ads on this site, so go to the Dallas Morning News story to see the thing. Trust me, you’ll want to do this.)

On the Trump-Palin thing, the question is does Palin’s endorsement make it less likely that any potential Trump voter backs away from him? I mean, if you’re already the kind of person who would vote Trump, does having Palin’s nod really turn you off?

I hope Reince Priebus’s staff has removed all sharp objects from his vicinity. Aren’t you glad you don’t have to manage the Republican brand after this year?

The Vile Charlie Hebdo

The French satirical journal has hit a new low, mocking a dead child:

The father of drowned Syrian toddler Alan Kurdi has told how he wept upon seeing a cartoon that mocked up his son as one of the migrant sex attackers in Cologne.

Abdullah Kurdi, whose son made front pages around the world when he died trying to reach Greece from Turkey last year, said the boy’s remaining family were “still in shock” after Charlie Hebdo printed the controversial image.

Editors at the French magazine had depicted 3-year-old Alan as a grown man chasing a woman, his arms outstretched towards her bottom.

In the top left-hand corner was a sketch of the iconic image splashed by hundreds of media organisations, captioned: “Migrants”.

“What would have happened to little Alan when he grew up?” editors mused. “He’d have groped women’s arses in Germany.”

It’s evil, and it’s not even remotely funny.

Non, je ne suis pas Charlie. They don’t deserve to be shot, heaven knows, but what disgusting humans they are. Mock religion? I can withstand that, foul as it may be. But to mock a dead little boy? Monsters.

Eating the Benedict Option

Now, this is just wild. From NPR:

There’s a new deli in rural Maine with a hotshot chef behind the counter. Foodies may know Matthew Secich’s name from stints and stars earned at Charlie Trotter’s, The Oval Room in Washington, D.C., and The Alpenhof Lodge in Jackson Hole, Wyo.

Recently, Secich joined an Amish community and moved his family and his kitchen off the grid.

His new spot, Charcuterie, is a converted cabin tucked away in a pine forest in Unity, Maine, population 2,000. You have to drive down a long, snowy track to get there, and you can smell the smokehouse before you can see it.

If you’ve followed your nose this far, inside, you’ll see ropes of andouille, kielbasa and sweet beef bologna hanging from hooks above the counter. There are no Slim Jims here, but rather handmade meat sticks, fat as cigars, sitting in a jar by a hand-cranked register.

More, about how life in the culinary spotlight failed to satisfy:

Something was missing, and Secich says he didn’t find what he was looking for until he adopted a traditionalist Christian faith and started to homestead. Happiness now, he says, is living off the grid, Amish.

Everyone in his family has had to adapt. His kids now take a pony to school instead of the bus. His wife, Crystal, stays home to care for the family.

Read the whole thing. Here’s more about his journey from the Portland (ME) Press-Herald:

His perfectionist streak ruled his actions. “I burned people,” he said. As in, held a line cook’s hand to a hot fire for making a mistake at Charlie Trotter’s restaurant in Chicago, where Secich was a sous chef from 2006 to 2008. “Four stars, that’s all that matters.”

Then he grew disgusted.

“I went home one night and got on my knees and asked for forgiveness,” he said. For his lack of compassion for others, his nights with restaurant friends and a fifth of Jim Beam with a side of Pabst Blue Ribbon, for that overactive ego. “I gave my life to the Lord, which I never would have imagined in the heyday of my chaos.”

Flood & Fatherhood

Father Matthew and the flooded Bayou Sara

Today is the Feast of Theophany in Old Calendar Orthodox churches. That means it’s the day we celebrate the baptism of Jesus in the River Jordan. After the liturgy, traditionally the congregation goes to a nearby body of water, prays more, and the priest ceremonially tosses a cross into the deep. We usually go to the Mississippi River bank, but this year, everything is in flood, so the river came to us. We gathered at the water’s edge, at the bottom of what folks here call Catholic Hill. The water you see is Bayou Sara in flood, as well as the Mississippi; when the flood waters rise around here, the bayou and the river merge into one.

Theophany has particular meaning for me. From How Dante Can Save Your Life:

In the Orthodox Christian tradition, Theophany – from the Greek, meaning “appearance of God” – is the feast day commemorating the day that Jesus Christ was baptized in the river Jordan. When Jesus emerged from the water, the heavens opened and the Holy Spirit descended like a dove, alighting on the Christ. The voice of the Father said, “This is my beloved son, in whom I am well pleased.”

Our little flock gathered at the mission on a cold Sunday morning — January 19, in fact — to celebrate the liturgy. Father Athanasius, an old friend of Father Matthew’s, was visiting from the Northwest, and gave the sermon. He dwelled for some time on the blessing God the Father spoke over his Son. I could have listened to that kind of talk all day.

This is my beloved son, in whom I am well pleased. Here, in the middle of the journey of our life, for the first time ever, I was able to hear those words in church and believe that God meant them for me too.

I don’t know when, exactly, in my healing process this change came over me. I had finished Paradiso over the Christmas break, but there had been no aha moment. I just noticed one day, a couple of weeks into the new year, that I felt pretty good. No chronic fatigue. No daily naps. Nothing. It was gone.

The night before Theophany, I mentioned to Julie that for the first time since arriving home, I felt at home. Settled. Stable. Healed. Free. Nothing had changed externally; the change was all within. But I saw the world with new eyes now.

Yes, the Epstein-Barr virus remains in my body, and always will, and in periods of stress—which crop up every now and then—it takes me back down temporarily. But nothing like before. The change has been profound.

When Father Athanasius spoke of Jesus rising out of the river, I felt as though I had come not only out of a dark wood but also out of some turbulent waters, into a new life. After he finished his sermon, I thought, Today is the day that I finally came home. Theophany is the day I finally turned outside of myself and let God the Father embrace me and welcome me into his household.

Here was a very nice Theophany gift: an extremely kind review of How Dante from the noted Catholic writer and apologist Karl Keating. Excerpt:

It used to be that nearly everyone read parts of The Divine Comedy in school—at least passages from the Inferno, often accompanied by Gustave Doré’s illustrations. In recent decades Dante has been dropped from the curriculum in most places (so has Shakespeare; so have many others), and today many people seem wary of picking up a book—particularly a book of poetry—written in the Middle Ages. What could such a book possible have to say to me?

Everything, really.

Wordsworth famously wrote that the Virgin Mary is “our tainted nature’s solitary boast.” Let me make an analogy: The Divine Comedy is our civilization’s solitary literary boast. There is more sense (and sensibility) in it than in anything other than Scripture itself. There is healing in it because there is healing in seeing ourselves as we really are.

Rod Dreher remains in St. Francisville. He was able to be reconciled with his father before the latter’s recent death, and the gulf between him and his sister’s children has been narrowed. He overcame physical and spiritual ailments that quite literally imperiled his health, and he found a sense of peace that had eluded him most of his life. After God, he gives Dante credit for this, because Dante led him back to God. Will Dante also lead him back to Dante’s Church? Who’s to say?

Flipping through my copy of How Dante Can Save Your Life, I see that I have penciled in double vertical marks along many paragraphs: my sign for things that are worth going back to, again and again. In not a few places I have found helps of the sort that I otherwise have found only in top spiritual writers. The book is that good.

Read the whole review. Thank you, Karl, for your kind words. Though I am firmly and gratefully rooted in Orthodoxy now, I receive the wish that I return to Catholicism in the generous spirit with which it is offered.

Nation First, Conservatism Second

If you read nothing else today, make it this brilliant column by Michael Brendan Dougherty, who says the late far-right nationalist writer Sam Francis wrote the script for Donald Trump’s campaign 20 years ago, for Pat Buchanan, but Buchanan was too much a Republican Party man to follow it. Excerpts:

To simplify Francis’ theory: There are a number of Americans who are losers from a process of economic globalization that enriches a transnational global elite. These Middle Americans see jobs disappearing to Asia and increased competition from immigrants. Most of them feel threatened by cultural liberalism, at least the type that sees Middle Americans as loathsome white bigots. But they are also threatened by conservatives who would take away their Medicare, hand their Social Security earnings to fund-managers in Connecticut, and cut off their unemployment too.

More, about how globalism and the free-market economics promoted by the GOP really has devastated the people Francis talks about:

The political left treats this as a made-up problem, a scapegoating by Applebee’s-eating, megachurch rubes who think they are losing their “jerbs.” Remember, Republicans and Democrats have still been getting elected all this time.

But the response of the predominantly-white class that Francis was writing about has mostly been one of personal despair. And thus we see them dying in middle age of drug overdose, alcoholism, or obesity at rates that far outpace those of even poorer blacks and Hispanics. Their rate of suicide is sky high too. Living in Washington D.C., however, with an endless two decade real-estate boom, and a free-lunch economy paid for by special interests, most of the people in the conservative movement hardly know that some Americans think America needs to be made great again.

And:

What so frightens the conservative movement about Trump’s success is that he reveals just how thin the support for their ideas really is. His campaign is a rebuke to their institutions. It says the Republican Party doesn’t need all these think tanks, all this supposed policy expertise. It says look at these people calling themselves libertarians and conservatives, the ones in tassel-loafers and bow ties. Have they made you more free? Have their endless policy papers and studies and books conserved anything for you? These people are worthless. They are defunct. You don’t need them, and you’re better off without them.

And the most frightening thing of all — as Francis’ advice shows — is that the underlying trend has been around for at least 20 years, just waiting for the right man to come along and take advantage.

Read the whole thing. You won’t see the GOP race the same way again.

You should also look at Sam Francis’s original 1996 essay in Chronicles. Trump may not get the nomination, and if he does, he may not become the next president. But in light of Francis’s column, it’s hard to see how Republican politics ever really return to normal after Trump.

Rod Dreher's Blog

- Rod Dreher's profile

- 507 followers