Barbara Sjoholm's Blog, page 4

July 3, 2022

Notes on EU-SAMI WEEK 2022

Between the recent conservative decisions at the Supreme Court and the January 6 hearings, I’ve been online a lot these days, trying to keep up with fast-moving events. But I also made time to stream panel discussions and catch videos on YouTube of the recent EU-SÁMI WEEK 2022, held in Brussels from June 20-22.

This event is described as “the first step in raising awareness among EU decision-makers about the need to include the Sámi people in EU policymaking.” Sámiráđđi, the Saami Council, a pan-Sámi organization based in Karasjok, Norway, was the prime organizer, along with Finnish Sámi Youth (Suoma Sámi Nuorat: SSN), in Utsjoki, Finland.

The Saami Council formally established an EU Unit in January, 2019, headed by lawyer and reindeer herder, Elle Merete Omma, a quiet but dynamic force much in evidence at the panels.

It's obvious that decisions made in the EU and decisions among member states, Finland and Sweden, impact the Sámi indigenous peoples of all the Nordic countries, including Norway. The EU-Sámi Week was designed to continue the process of "filling in the knowledge gaps" on both sides. The EU needs to know more about culture, heritage, and economics in Sápmi, and the Sámi people need to know more about how the EU functions, so as to be able to work more effectively with the EU to address issues of concern.

As was pointed out in the opening panel, the EU is very supportive of Indigenous people, but their proclamations have often applied only to Indigenous people outside the EU. The Sámi, as is well-known, are the only Indigenous people within Europe. The panelists pointed out three areas where EU policies impact Sápmi. Some of the clean energy projects promoted by the EU are actually harmful to the people and animals of Sápmi. Many of the solutions to the current climate crisis promoted by the global community have an impact on traditional ways of life, in Sápmi as well as other Indigenous areas. There is often little input from Sámi about where these some of these energy projects are located. The panelists also described how, although member states receive funding from the EU, little of that generally goes to the Sámi. Thirdly, the panelists mentioned that many EU regulations that directly impact the Sámi are often imposed without input from the Sámi, and that exemptions are not discussed. More on the panel discussion on Climate Justice to come in another blog. I'm still thinking about the issues that came up when I watched this particular panel and the questions it raised raise about underlying assumptions around resources and sustainability.

May 12, 2022

Girjegumpi. Sámi Architectural Library

I found this site about a recent exhibition by Joar Nango on the website of the National Museum-Architecture in Oslo:

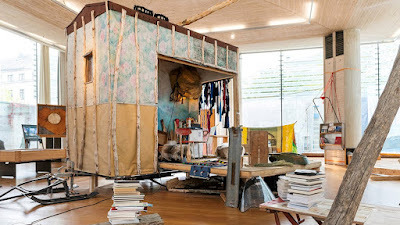

"The architect and artist Joar Nango has for several years collected books and other materials relevant to Sámi architecture. The title Girjegumpi is derived from two North Sámi words: "Gumpi" is a mobile cabin on runners, most often pulled by a snowmobile. "Girji" means book. The compound word, and the work Girjegumpi, include a library, an archive and the construction in which these are stored and transported.

"Nango's collection includes literature on Sámi building customs, indigenous architecture in general, architectural theory and postcolonial theory. It is also an artistic project and a platform for investigation and discussion. What actually is Sámi architecture? What can Sámi architecture be? When is architecture an exercise in oppression? And what is the role of the architect in the overall process?

"Girjegumpi is a nomadic project that changes in different situations and contexts. It was exhibited for the first time in Harstad in 2018, during the Arctic Arts Festival. It has also been exhibited at the winter market in Jokkmokk, at the National Museum of Canada, and during the Bergen International Festival. When Girjegumpi is not travelling, it is based at the Sámi Center for Contemporary Art in Karasjok."

Excerpts from some of the books in the exhibition, interviews with Joar Nango about his philosophy of Sami space, duodji, and architecture can be found on the virtual Girjegumpi site:

April 18, 2022

A short list of great books about Sápmi

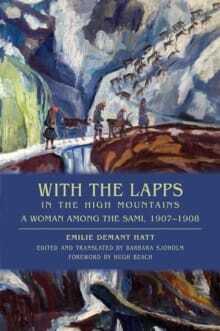

Once again, I had the chance to recommend some books for Shepherd, a book discovery website. Last time it was books by and about seafaring women. This time it's books about Sápmi, including one of my favorites, With the Lapps in the High Mountains by Emilie Demant Hatt, which I translated from Danish about ten years ago. I wrote:

I’ve long loved the adventure, humor, and visual feast in this book, first published in 1913, and was eager to translate it and share it with readers curious about the high north of Scandinavia. Demant Hatt was a brilliant observer and an early immersive journalist who didn’t shy away from hard work, rough conditions, and learning the Sami language.

For more recommendations, check them out here.

April 5, 2022

Jenni Laiti, artivist from Sápmi

Jenni Laiti calls herself an “artivist.” An environmental artist and activist for Sámi and Indigenous rights and for climate justice, she was born in Inari, Finland into a family of makers. She studied duodji and Sámi culture at the University of Umeå in Sweden and she now lives in Jokkmokk. She describes her work as “a mixture of cultural intervention, installations, and performative direct action, dealing with colonialism, decolonialism, climate justice, and the Sámi people’s rights to their own culture and land.”

Jenni Laiti calls herself an “artivist.” An environmental artist and activist for Sámi and Indigenous rights and for climate justice, she was born in Inari, Finland into a family of makers. She studied duodji and Sámi culture at the University of Umeå in Sweden and she now lives in Jokkmokk. She describes her work as “a mixture of cultural intervention, installations, and performative direct action, dealing with colonialism, decolonialism, climate justice, and the Sámi people’s rights to their own culture and land.” Yesterday I listened to a Zoom presentation Laiti did for the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico: “For the next thousand years: A presentation on crafting another world.” She spoke about the importance on non-linear time within landscapes and about the social dialog between nature and people implicit in the art of crafting duodji.

Jenni Laiti also has discussed her work as an artivist in a recent essay for the Kone Foundation, “Art is free when we are free.” She asks “What if we saw making art as a form of being and creating, instead of limiting to activities performed only by certain people? What if we saw art as belonging to everyone because it is part of humanity? Art could live freely, available to everyone, if we set it free.”

Her work comes out of community and is for community. I’m interested in how Laiti shifts the usual paradigm of traditional vs. innovative when it comes to making art and craft. By foregrounding heritage and community, she honors Sápmi culture. But her own installations are more contemporary and beautiful in ways that aren’t traditional “useful,” but rather draw our attention to an ecological issue and to a political response.

In her Zoom presentation for MIFA she discussed the environmental struggles going on now in Sápmi between local Indigneous communities of reindeer herders and others who depend on an intact ecosystem in traditional lands, and foreign and state investors abetted by the Nordic governments. While there have been some successes in fighting, for instance, the wind farms in Sámi homelands in Norway, the number of ongoing conflicts in Sápmi around the environment still persist. In Gállok outside Jokkmokk, where Laiti lives, the British-owned Beowulf iron mine recently got the go-head from the Swedish government, even after the mine has been condemned by the Sámi parliament and the United Nations. Laiti has been active in opposing the mine for many years. She also is part of the Ellos Deatnu! group [Long Live Deatnu!], which supports efforts in the high North to protect the Deatnu, or Tana River, area.

In 2016 the Art Ii Biennial, which hosts site-specific artworks by international artists in the town center and environmental art park of Ii, Finland, on the Gulf of Bothnia, chose eight Sámi artists and/or duojárs to participate in a project titled “The Poetics of Material.” The thematic intent was to look at environmental art and the use of natural materials. . They titled their work “Ovdavázzit/ Forewalkers,” to recognize and honor the Sámi ancestors. The ovdavázzit echo the way past walkers decorated their personal staffs; some of the materials, such as copper and colorful yarn, point to the fact that the Sámi also used material from other cultures.

I’m pleased that my publishers, the University of Minnesota Press, and I agreed that we would like to have a photograph of Ovdavázzit/Forewalkers in my upcoming book, From Lapland to Sápmi: Collecting and Returning Sámi Craft and Culture, and that I could talk briefly about Jenni Laiti’s work in the context of contemporary Sámi artists and artisans.

“Ovdavázzit/ Forewalkers,”

“Ovdavázzit/ Forewalkers,”

March 14, 2022

Recent Books about Sápmi in English (#2): Duodji Reader edited by Harald Gaski and Gunvor Guttorm

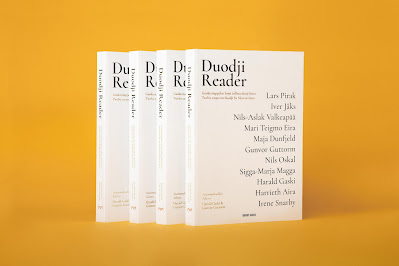

The Duodji Reader is a new publication from the Sámi publisher Davvi Girji in Karasjok, Norway. Edited and with an introduction by Harald Gaski and Gunvor Guttorm, the twelve essays circle around the subject of Sámi artisanship, generally from a historical and theoretical perspective. The large, handsomely designed paperback is bilingual—North Sámi and English—and includes essays by several key duojárs or artisans from the past and by contemporary scholars and curators, as well as color photographs of modern-day duodji.

Duodji (pronounced something like “dwotchi” though I’ve also heard it as “dwodji” and “dwerchi”) is usually translated as handicraft. The making of Sami objects for domestic use, everything from ceremonial drums, sleds and skis, clothing and shoes of fur and fabric, milking bowls, decorated spoons, knives with etched sheaths of bone, root baskets, bentwood chests, toys and tools, has been part of Sámi culture for many hundreds of years. Duodji was described and collected as early as the 1600s by such scholars as Johannes Schefferus. Tourists bought duodji from Sámi individuals and curio shops in the 1800s. Nordic museums amassed piles of Sámi handiwork through the 1900s, cataloguing the objects variously as ethnographic and artistic.

Per Thomas Aira Balto: from Duodji Reader

Per Thomas Aira Balto: from Duodji ReaderAlthough the editors of this Duodji Reader peg the revitalization of duodji to the 1970s in their introduction, it’s been my impression that renewed interest in duodji was already stirring in the 1930s and 1940s, when a variety of Sámi artisans and educators like Karin Stenberg and Gustav Park in Sweden saw passing on artisanal skills to a younger generation as an important step to conserving the past and creating a new political and cultural future.

Offering classes in duodji in Sámi schools often went hand in hand with teaching language. Soon after WWII, a folk high school in Jokkmokk grew into an institution. The Sámi Training Center (Sámij åhpadusguovdásj) today teaches a wide range of classes in duodji, along with reindeer herding, food preparation, and the Lule Sámi language. The school’s students display their craftsmanship at the well-known Winter Market in Jokkmokk and some settle in the community to continue to make and sell their work. Sámi Allaskulva/Sámi University of AppliedSciences in Kautokeino, Norway is another important teaching institution where students learn North Sámi and can study duodji. Editor Gunvor Guttorm, who teaches there, is the first professor of duodji with a doctorate; she has written extensively on the topic of duodji as a component of Sami education.

The Duodji Reader, with previously published contributions from the 1960s by duojárs and artists Lars Pirak from Jokkmokk and Iver Jåks from Karasjok, along with a number of pieces from the past ten years, is a rich source of texts about duodji as personal expression and process. The theoretical contributions, such Harald Gaski’s essay on Indigenous aesthetics, makes an attempt to articulate a larger epistemological perspective, as does “Meaning of Sámi Culture in the Brand Building of Dudoji” by Sigga Marja Magga. Other essays explore particular objects, winter clothing or the milking bowl. Maja Dunfjeld, in “Form and Content in South Sámi Ornamentation,” writes about Traditional Knowledge and explores some of her family history in South Sápmi, and how that shapes her work as an artisan and lecturer on duodji (or duedtie as it is written in the South Sámi language). I found this piece particularly insightful on the subject of how skills are transmitted both technically and orally.

I also enjoyed “A Conversation with Perisak Juuso,” in which the author Irene Snarby and her husband make a visit from their home in Tromsø to the workshop of Juuso in Northern Sweden. Juuso discusses with them his different projects and the natural materials he uses, as well as his family background and how he came to duodji.

Petteri Laiti at SDG

Petteri Laiti at SDGThe liveliness of this encounter with a working duojár made me wish there had been more interviews with contemporary duojárs and artists who use craft techniques long-established in Sápmi to make traditional objects as well as innovative new work. I’m thinking of someone like Petteri Laiti from Finland, a pioneer in the field, who works with reindeer horn and skin, as well as silver, gold, and wood. He began to work with duodji in the 1960s, later studied in Jokkmokk and attended goldsmith school in Finland. His work is highly valued and often exhibited, and there are many others who might well have been profiled to give a more well-rounded sense of what a meaningful career in duodji looks like.

Likewise, in her article “An Absence of Women’s Duodji and Duddjon, “ Gunvor Guttorm, herself a fine duojár, discusses a long-standing preference on the part of collectors for crafts, including knives and engraved spoons, made by men. It would have helpful to balance that critique by including essays or interviews with some of the very well-known Sámi women duojárs and artists whose work is informed by duodji, such Britta Marakatt-Labba, Rose-Marie Huuva, and Outi Pieski, and whose objects and installations are intimately influenced by traditional female practices of needlecraft and leatherwork, as well as making use of wood, metal, bone materials and techniques more generally associated with male duojárs.

But these notes and suggestions aside, Duodji Reader is a fascinating and necessary compendium of older and newer writings in one book, about an increasingly important topic for anyone interested in Sámi culture past and present.

The Duodji Reader is jointly sponsored by Sami Allaskulva and Norwegian Crafts, which has some photographs and supplementary material about the book and contributors on its website.

A panel featuring Harald Gaski and Gunvor Guttorm is available on YouTube from Scandinavia House.

February 15, 2022

Recent Books about Sápmi in English (#1) : Liberating Sápmi, by Gabriel Kuhn

For the past twenty years, there have been comparatively few popular titles published in English about the Sámi people. Even fewer have mentioned contemporary political movements in Sápmi and the relationship between Sápmi and the Nordic countries and Russia. This, in spite of the fact that activism in many areas of Sámi society has been steadily on the rise, in part fueled by a younger generation and social media. While there’s a fair amount these days to be found online in English on Sámi art, duodji (handicraft), joik, and political resistance, that hasn’t fully been reflected in book publishing until the last few years.

[image error]

One of the new crop of titles is Liberating Sápmi:Indigenous Resistance in Europe’s Far North, by Gabriel Kuhn, out in 2020 from PM Press, an independent radical press in Oakland, California.

Liberating Sápmi is an up-to-date book of interviews with twelve engaging and thoughtful activists from Sápmi, proceeded by an introductory political history of Sápmi by Gabriel Kuhn. Kuhn is Austrian by birth; he has lived in Sweden since 2007. He says in his preface that he was motivated to work on this book by his “frustration at the lack of interest in the Sámi among the majority populations of the Nordic countries.” (I’ve often found this as well).

Kuhn has clearly spent time grounding himself in Sámi history, past and present, and his introduction covers many of the core events of the past four centuries of colonization in Sápmi, from the closing of the borders and forced removals of Sámi herding siidas, to the Kautokeino Uprising of the 19th century, to protests over the last fifty years against mining, logging, wind farms, and damming and damage to rivers and fjords. He gives background as well on how the Nordic states both control and work with their Sámi citizens, and how the Sámi have also forged important connections with Indigenous people all over the world. For anyone hoping to get a succinct perspective on the complex realities that Sámi people face within the Nordic countries (particularly Sweden and Norway), this is a outstanding resource. Kuhn’s leftist politics are visible, but he’s very clear that he is reporting, not prescribing, and that as a sympathetic outsider, his job is to reflect and amplify the varied voices of a variety of Sámi artists, activists, academics, and politicians.

In order to do so, in 2019 he interviewed twelve well-known figures in Sápmi, beginning with the artist/poet/arts organizer Synnøve Persson (b.1950). Her personal story as a young Sámi woman who came from Finnmark to attend the university in Oslo, only to return and help found an artists’ collective in Máze, is intertwined with the Alta River struggle of 1979-1982, when many hundreds of people took action to try to stop the river from being dammed and to protest and hunger strike in front of Norway’s parliament building in Oslo. Such intertwined stories play a part in many of the interviews, including the last one, with well-known actor, rapper, and activist, Maxida Märak (b. 1988), an outspoken critic of the proposed UK mining operation outside Jokkmokk (Jåhkåmåhkke) in Gállok. Other interviewees include the filmmaker Suvi West; the teacher and translator Harald Gaski; the salmon fisherman Aslak Holmberg from the Finnish side of the Tana River; the world famous singer Mari Boine; the queer politician and reindeer herder Stefan Mikaelsson; and the avant-garde artist Anders Sunna. In spite of different backgrounds, professions, and generations, all share a vision of what Sápmi means and ways they want to contribute to visibility, acknowledgement, and positive futures.

Unsurprisingly, many of those that Kuhn interviews speak of some of the same events and subjects from different perspectives, so in addition to learning more about the interviewees themselves, we see the tapestry of Sámi history over the past fifty years. Through their eyes we understand the range of obstacles that the Sámi face and have often faced, individually and collectively. Too often when journalists and travel writers mention the Sámi in the media, they speak of discrimination as something that happened in the long ago. In fact, as Kuhn reminds us and many the interviewees attest, racism, both structural and personally aggressive, is sadly alive and well in the Nordic countries.

If I have one criticism of Kuhn’s book, it would be that his introduction is not as nuanced as the stories told by the remarkable people he interviews, who have not only lived through Sámi history in their own lives, but who are familiar with many other stories from parents and elders. Kuhn focuses in his political history of the Sámi on oppression and resistance; he places special emphasis on periods of conflict. In his summary, not much happened politically in Sápmi from the stirrings of pan-Sáminess in the first two decades of the twentieth century to the full-blown fight for justice that came to characterize Sámi culture in the 1970s. But in fact, through the middle of the century, Sámi people were continuing as culture bearers, establishing schools that taught the Sámi languages and the art of duodji (handicraft), and forming organizations that were the precursors to state-funded institutions today. In Sweden, teachers like Karin Stenberg and Gustav Park were crucial figures in conserving and promoting Sámi culture, while at the University of Uppsala, Sámi professor Israel Ruong published articles and books and encouraged a new generation to study Sámi linguistics and history. The same happened in Norway and Finland. The ground for many of the demands made in the 1970s was prepared by hundreds of active Sámi artisans, teachers, and politicians in mid-century Scandinavia.

Nevertheless, both Kuhn’s introduction and particularly the interviews, make this an excellent primer on past and present Sámi activism. Liberating Sápmi stands out in acknowledging Sámi agency and introducing concepts of indigenous community, heritage, and sovereignty in the European North, as well as raising questions about the pervasive view of the Nordic countries as somehow perfect societies.

I can’t think of a better introductory book I’d want to place in the hands of someone who wants to know more about Sápmi and doesn’t know where to start.

February 11, 2022

Greta Thunberg condemns UK firm’s plans for iron mine on Sami land

A British company has fallen foul of Greta Thunberg, Unesco, Sweden’s national church, and the indigenous people in the north of the country over plans for an open-pit mine on historical Sami reindeer-herding lands.

The clamour of opposition was voiced as Beowulf Mining, headquartered in the City of London, suggested it was “hopeful” of a decision within weeks of a 5 sq mile iron-ore mine in an area where Sami communities have lived for thousands of years.

from the Guardian February 11, 2021.Read the whole article

January 29, 2022

Sámi drum repatriated to Sámi Museum by Denmark

On January 24, 2022, a seventeenth-century Sámi drum passed into the ownership of the Sámi Museum (RDM) in Karasjok, Norway. In a rare act of repatriation, the National Museum of Denmark formally transferred the drum, which had been at the Sámi Museum on deposit since 1979.

This sacred drum had been the prized possession of the Sámi Anders Poulsen (Poala-Ánde), a herder in Finnmark, Norway, who brought his reindeer to the Varanger Fjord seasonally, and who had learned the noiadi arts from his mother. He was caught up in the witchcraft hunts of the seventeenth-century, and one of the last to be convicted. After his arrest in 1691, he was brought to Vadsø, a fishing town on the coast and the administrative center of East Finnmark. This was in the period when Denmark ruled Norway from Copenhagen through governors and magistrates appointed in Copenhagen.

Sacred seventeenth-century Sami drum

Sacred seventeenth-century Sami drumImprisoned in Vadsø, Poulsson was interviewed and charged with “diabolic sorcery,” and eventually put on trial. The main evidence against him was that he owned and used a sacred drum, which was by this time forbidden by law, both by the church and state. He had no lawyer, only a translator who was also on the side of the prosecution. His answers to his interrogation formed most of his written “confession,” which was then used as a basis for the trial. The drum itself, as Exhibit A, was on trial as well, an object of fascination and revulsion to the magistrate and prosecutor.

Anders Poulsson was convicted, but his sentence was postponed until the authorities in Denmark could weigh in. Only a day after the verdict, as Poulsen lay sleeping, a young male servant known for his unstable and bizarre behavior murdered the Sámi elder with three blows of an axe, explaining that he was a sorcerer and deserved to die. There was little justice in this case, given that Poulsen had already been found guilty and would have been executed anyway—a decision confirmed by the high court in Denmark the following year. The children of Poulsen petitioned for half of the money raised from selling Poulsen’s reindeer for their mother’s welfare.

Once Anders Poulsen was dead, his drum belonged to the Danish crown. It was not destroyed but sent down to Copenhagen, where it became part of the Royal Kunstkammer, and eventually the Ethnographic Collection in the National Museum of Denmark. It is one of only a few drums remaining whose figures were explained in some way by its original owner.

The museum in Karasjok keeps the original in climate-controlled storage and displays a replica in the exhibition hall. Another facsimile copy is on display at the Varanger Sámi Museum near Vadsø, where the trial took place over three hundred years ago. The replica is painted with red pigment made from alder bark, symbolizing blood.

The Norwegian Sámi Parliament has been negotiating with the National Museum for many years for the return of the drum, and as the new renewal date approached in December, 2021, the negotiations became more intense, with the then-president of the Norwegian Sámi Parliament, Aili Keskitalo, raising the question of repatriation with the UN and EU. Keskitalo even made a public request to the Queen of Denmark to draw attention to the issue.

In January, 2022, the Danish Cultural Minister, Ane Halsboe-Jørgensen, announced that the National Museum would remove the Sámi drum from the Danish museum’s holdings, stating that it made sense to do so, since there was a historical connection to the drum in that area of Norway, and it had been displayed at the Sámi Museum for so many years. She added in a press release that “Normally, there is no question of removal to museums in other countries, but in this specific case, permission has been granted.”

Meanwhile, in Karasjok the reaction was jubilant. Sámi Museum director Anne May Olli told a reporter for the Norwegian paper VG, “It feels good to have formal ownership to something that is already ours. And that our own cultural heritage is recognized. It is important not only for us, but for the whole of Sápmi.”

January 24, 2022

My favorite books on women seafarers and pirates

I just had the opportunity to recommend some of my favorite reading about women and the sea for the new book browsing site, Shepherd.

The five books include stories about pirates and intrepid women sailors, including one of my all-time favorites, My Ship Is So Small, by Ann Davison, who crossed the Atlantic in her 23-foot yacht in the 1950s.

June 24, 2019

Do You Need to Write in Sami to be a Sami Author?

It’s perhaps not widely known that Norway practiced sustained and systemic discrimination against its Sami population for several centuries, discrimination now known as Norwegianization [fornorsking].

As described on Wikipedia, Norwegianization (Fornorsking av samer) was an official policy carried out by the Norwegian government directed at the Sami and later the Kven people of northern Norway to assimilate non-Norwegian-speaking native populations into an ethnically and culturally uniform Norwegian population.

One of the results of the prohibitions against schooling in the Sami language (largely Northern Sami as spoken in Norway), including sending many Sami children to boarding schools away from their families, is that a great number of Sami, especially those who grew up outside certain districts in Sápmi, such as Finnmark, never learned the language. Finland and Sweden had their own forms of suppressing Sami languages and culture.

What does that mean for Sami literature, and for authors who identify as Sami but who write in one of the Nordic languages, either to reach a wider audience or because in many cases they never learned one of the Sami languages due to state policies that discouraged or forbade it?

Linnea Axelsson, author of Ædnan

Linnea Axelsson, author of ÆdnanIn Sweden, it is notable that the esteemed August literary prize for 2018 was awarded to Ædnan, by Linnea Axelsson, a Sami author from Porjus. Ædnan, written in Swedish as an epic poem, is almost 800 pages long. You can read an excerpt in Saskia Vogel’s translation, published in Words Without Borders, and interview between Axelsson and Vogel here. The book has received rave reviews in the Swedish press. For many readers it brought the history and struggle of the Sami in Sweden to life for the first time.

Today I happened to read an article in Norwegian, originally posted on NRK on June 20, 2019 and cross-posted on the website of the Norwegian Writers’ Union about recent rules in the Sami Authors’ Union that prevent Sami authors who don’t write in Sami from becoming members of the association.

I’ve translated it into English below:

Historically untrue and discriminatory

Several authors respond to the Sami Authors' Union excluding Sami who do not write in Sami. This has created great divisions. After this year's annual meeting, it was made clear that Sami who don’t write in a Sami language cannot become a member of the union. If you write in Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish or Russian, you are thus excluded. If you are not a member, you also cannot receive a fellowship or be nominated for the Nordic Council Literature Prize.

Author Susanne Hætta believes it is shocking that the union is excluding "their own." She says, “I think it's historically untrue, it's exclusionary, and it's discriminatory.”

Hætta herself writes in Norwegian, and became a member before the membership criteria changed last year. Despite resistance, a change of last year's decision was voted down in the recent annual meeting. Hætta believes "language discrimination" is extra-shocking when the reason why many Sami do not have Sami as their mother tongue is former Norwegian-language policy.

And Hætta is not the only member of the writers' union that is shaken. Lene E. Westerås believes the decision is in violation of the Gender Equality and Discrimination Act. “What was adopted is against Norwegian law and it was initiated by racism. I get chills in my body thinking about it.”

The chair of the Sami Authors’ Union, Inga Ravna Eira, says that the reason for the decision has to do with concerns that an increasingly smaller part of the Sami population speaks Sami. She responds to the criticism: “I can understand their reactions very well. But our intention was to save the Sami language. It was not our goal to discriminate against anyone. But when making such a decision, these are the consequences.”

Eira is supported by the deputy chair Karen Anne Buljo: “I respect the members' feelings, but we are in the middle of Norwegianization [fornorsking] which is completely unstoppable. Therefore, it is important to take a position.”

Susanne Hætta criticizes the leadership style, believing that they now have an authors’ union that that appears anything but unified. “We are a divided union. The leader used a divide-and-conquer technique, and it has worked well for what she has tried to do.”

Eira denies that she has tried to divide the union, only to protect the Sami language.

But Susanne Hætta still believes that the decision is a loss, not just for the authors who can’t get membership, but for all of Norwegian literature. “It is wounding, it is very sad for all those who cannot write in Sami. And Sami literature is not just related to the "correct" language.

Susanne Hætta and Lene E. Westerås

Susanne Hætta and Lene E. Westerås[image error][image error]

I