Barbara Sjoholm's Blog, page 3

April 13, 2023

Sámi Events at Scandinavia House in New York and online, April 2023

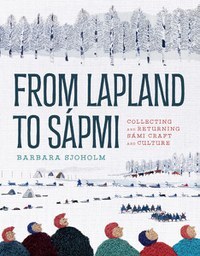

First of all, a quick reminder that I'm doing a virtual talk with slides from my new book, From Lapland to Sápmi TUE—April 18—7 PM EST from Scandinavia House in New York. It's a free on Zoom, but you'll need to register at https://scandinaviahouse.org/events/from-lapland-to-sapmi/. It will later be available on their YouTube channel.

This is a big week for Scandinavia House in their efforts to highlight Sámi and Indigenous people. On April 15 the exhibition, "Arctic Highways: Works by by Twelve Indigenous Artists from Sápmi, Canada, and Alaska opens there. Running through July, the exhibition is curated by Indigenous artists Tomas Colbengtson, Gunvor Guttorm, Dan Jåma and Britta Marakatt-Labba, the exhibition includes their own works alongside those of artists Matti Aikio, Marja Helander, Laila Susanna Kuhmunen, Olof Marsja, Máret Ánne Sara, Sonya Kelliher-Combs, Maureen Gruben and Meryl McMaster.

As a special opening event on Saturday, April 15,there will be a performance and film screening. Greenlandic dancer Elisabeth Heilmann Blind will perform “UaaJeerneq – the Greenlandic Mask Dance,” followed by a screening of Historjá – Stitches For Sápmi (dir. Thomas Jackson), depicting artist Britta Marakatt-Labba’s battle for her culture against the threats of climate change. Next, Sámi Yoiker Lars-Henrik Blind will perform, followed by a panel with Britta Marakatt-Labba, Thomas Jackson, Elisabeth Heilmann Blind and Tomas Colbengston. Learn more and register.On April 21 & 22, American-Scandinavian Foundation and the Arctic Indigenous Film Fund AIFF present a special film event “Climate Action — Future Changes,” exploring the Arctic Indigenous peoples’ fight against climate change through films and media. The program will begin with a panel discussion and reception on Friday, April 21, followed by film screenings on Saturday, April 22.

[From their website] "Arctic Indigenous peoples have a vivid and active storytelling tradition, with stories that have played an essential role in maintaining sustainable living in the Sámi and other Indigenous people’s traditional living areas. By telling their own stories and being in charge of their narratives, they create a new future for their people. This is why all Indigenous peoples must have the ultimate right to tell their own stories about climate change in the Arctic tipping points — ice caps melting, permafrost collapsing, and changing the Oceans and vanishing the snow. How we can fight back?

"In this two-day program held in coordination with the UN Permanent Forum for Indigenous Issues 2023, tonight will feature a panel discussion with film director Elle Máijá Tailfeathers (Sámi/Blackfoot, Canada), film producer Emile Hertling Péronard (Inuk, Greenland), director Anna Hoover (Unangax̂, USA), and AIFF’s Liisa Holmberg (Sápmi), moderated by Jason Ryle (Canada). Welcoming notes to the program will be provided by Dariio Mejia Montalvo (Chair of the Permanent Forum for Indigenous Issues), Aslak Holmberg (President, Saami Council), and Petteri Vuorimäki (Ambassador for Arctic Affairs, the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland). The discussion will be followed by a screening of the documentary short Salmon Reflection (dir. Anna Hoover, Alaska, 2022), and a reception. "

January 14, 2023

Maria Persson, Who Taught and Inspired Karl Tirén, Joik Musicologist

A post on February 17, 2008, about the Swedish collector of joik music, Karl Tirén, has always been one of my most popular offerings on Northwords. I suspect it’s because it turns up in searches on joiking, and Tirén was a key figure in recording joik music in the Swedish part of Sápmi in the early twentieth century.

Greta Persson, Maria Persson and Karl Tirén in Arjeplog, 1937

But Karl Tirén’s work couldn’t have been accomplished without the insight and traditional knowledge of his friend Maria Persson, from Arjeplog in Pite Sápmi, a highly talented joiker and a seamstress.

During the last few years I’ve learned much more about Maria Persson, who is only mentioned in passing in the 2008 blogpost, and about her life and collaboration with Karl Tirén. A chapter in my upcoming book, From Lapland to Sápmi, is dedicated to exploring Tirén’s collection of wax cylinders of joiks (now at the archives of Musikverket in Stockholm). I emphasize the key role Maria Persson and other Sámi played in Tirén's years of collecting, recording, and writing about the joik.

Here's a brief excerpt from “Wax Cylinders, Sámi Voices”:

Maria Persson was born in the mountain district of Luokta-Malvas, just south of the Arctic Circle, one of fifty-one districts carved out of Swedish Sápmi during the reindeer herding act of 1886...Maria’s parents were nomadic herders, and she grew up in a traditional siida,a community that still actively recalled and passed on stories and joiks. Her parents gave up the migratory life in the 1890s, and like many Sámi of the period, they became smallholders, with a farm outside Arjeplog; they raised goats and sheep, along with a few reindeer. In her teens Maria suffered an accident to her hip or back and was sent to the town of Piteå on the coast, where she lay in hospital for two years “in a plaster cradle,” according to her daughter in an interview years later....In Piteå she would have spoken Swedish nearly all the time; her fluency put her in the position of being able to negotiate the borders of Sápmi and Sweden. Perhaps it was for that reason she was asked to go to Stockholm in 1909 for the Industrial Arts Exhibition to help represent the large province of Norrbotten.

This exhibition followed on the world’s fair held in the city in 1897, an extravaganza that introduced Stockholm’s culture and industrial products to the world and that coincided with Artur Hazelius’s founding of Skansen and plans for the Nordic Museum. In the midst of “the summer city,” as the Industrial Arts Exhibition came to be called, a Sámi couple were invited to display themselves and their belongings as an example of nomadic life in northern Sweden. In the Norrbotten rooms they set up their tent and lit a campfire to boil coffee and make food. The fire created a ruckus with the managers of the exposition. Maria Persson stood up for the Sámi couple. A tent without a fire was not a home at all. Surprisingly, she was joined in her protest by a big Swede with a short beard whom she had met at the exposition. Karl Tirén was in Stockholm to show his paintings over in the Jämtland rooms. He too argued with the directors over the importance of the campfire....

When the Sámi couple decided to pack up and leave the Stockholm exposition, Maria went with them, and so did Karl Tirén. A short time later, Maria arrived as an invited guest to the home that Karl shared with his wife, Karen, and their five children in Boden. Tirén had long wished to hear true joiking and to learn more about the Sámi’s musical traditions. Over the course of a few days, Maria Persson shared joiks and explanations, and he noted down her words and melodies as best he could. In letters at the time and later in his published work, he emphasized the importance of his meeting with her: “What I learned from Maria Person . . . in the form of both tones and information on the character and concept of Lapp song greatly increased my interest and evoked the idea of making journeys to collect and research in this field.”

You can listen to Maria Persson and her sister Greta joiking by opening one of the historical Tirén collections on CD or online at Musikverket.

January 5, 2023

Prepub discount sale from University of Minnesota Press for From Lapland to Sapmi through March 1, 2023!

Get 40% off From Lapland to Sápmi (coming in March '23!) when you order at z.umn.edu/lsmla using code MNMLA23. This is part of @UMinnPress's Humanities and Arts sale, the full list of which can be found at z.umn.edu/mla23. Offer expires March 1.

December 26, 2022

Reindeer herders fear Arctic industry boom

A well-researched article on the BBC website about challenges facing the Sami as the so-called Green Revolution pushes forward with more mining and wind farming in Northern Sweden, Norway, and Finland. Depressing but crucial reading.

December 23, 2022

November 29, 2022

Over the Border to Asylum in Norway: Russian Sami Andrei Danilov's story

Andrei Danilov Photo: Thomas Nilsen

Andrei Danilov Photo: Thomas Nilsen

The always interesting Barents Observer, which covers politics and life in the European Arctic, has this story today on Andrei Danilov. Born in Lovozero, the main Sámi settlement in Russia's Kola Peninsula, Danilov fled Russia for Norway in February, 2022 when Russia invaded Ukraine. He is currently seeking asylum in order to stay in Norway.

For the past thirty years, the Russian Sámi have been part of the Sámi Council representing all Sámi in the four countries, Russia, Finland, Norway and Sweden. Now that cooperation has been suspended, in part due to the fact that some of Sámi on the Russian side are actively supporting Putin's actions.

I found this development distressing to read about, given how harshly the Sámi themselves have been treated by the Russian state, and how meaningful it's been for the Sámi in every part of Sápmi to be able to connect and work together.

Several other cross-border long-term cooperations are also being suspended in the face of the continuing war in Ukraine, as reported by High North News. They include The Norwegian Barents Secretariat and Barents Press International, "a network for journalists and editors in the Barents region in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia. The network was founded after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union at the start of the 1990s."

November 9, 2022

From Lapland to Sápmi: Collecting and Returning Sámi Craft and Culture

It's been over three years since I first began to write this book, during a time before the pandemic, when I imagined long days in libraries and even a research trip to Scandinavia. How differently it turned out! Six months or so into the book the libraries closed and I postponed my trip, as it turned out, indefinitely. But through colleagues, friends, and complete strangers in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Denmark, as well as librarians and booksellers, I managed to get the materials I needed and keep going. In fact, sometimes the marvelous things I learned and read made up for the fact that I was stuck at home for months, like most of you.

It's been over three years since I first began to write this book, during a time before the pandemic, when I imagined long days in libraries and even a research trip to Scandinavia. How differently it turned out! Six months or so into the book the libraries closed and I postponed my trip, as it turned out, indefinitely. But through colleagues, friends, and complete strangers in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Denmark, as well as librarians and booksellers, I managed to get the materials I needed and keep going. In fact, sometimes the marvelous things I learned and read made up for the fact that I was stuck at home for months, like most of you. Yesterday, I finished reviewing the substantial index, and soon the book is off to the printers, with a publication date of March 19, 2023. I am so thrilled to think of this project in final form. The University of Minnesota Press has once again been such a delight to work with, and they have really expended a lot of time and resources on adding b/w and color illustrations and coming up with a fantastic cover design based on Sámi artist Britta Marakatt-Labba's textile art, History.

Look for more about the contents in coming blog posts. Meanwhile, here's some of the advance publicity:

[from the catalog] The story of the Indigenous Sámi living in Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia unfolds across borders and centuries, in museums and private collections. Deftly written and amply illustrated, From Lapland to Sápmi brings to light the history of collecting, displaying, and returning Sámi material culture, as well as the story of Sámi creativity and individual and collective agency.

"An important contribution to Sámi stories of loss, recovery, and the struggle for equality, as well as the right to manage one’s own cultural heritage on one’s own terms. As Barbara Sjoholm charts the transformation of Lapland to Sápmi in objects, joiks, and storytelling, Sámi voices emerge to share essential aspects of their history. As we say in Sápmi, ‘Čálli giehta ollá guhkás—A writing hand reaches far.’" —Káren Elle Gaup, coeditor of Bååstede: The Return of Sámi Cultural Heritage

"Barbara Sjoholm’s From Lapland to Sápmi chronicles in vivid words and images the colonial encounters of Sámi and non-Sámi as told through the objects, images, and recordings that eventually became sequestered in Nordic museums and archives. It also tells the inspiring story of efforts to recover and return these items to their rightful communities as part of Sámi decolonization and self-determination." —Thomas Dubois, coauthor of Sámi Media and Indigenous Agency in the Arctic North

"Fascinating and important, From Lapland to Sápmi presents a nuanced and enlightening look at the cultural history of objects and collections originating in Sápmi. With rich detail and riveting storytelling, Barbara Sjoholm presents a diverse picture of the north and its entangled histories of collecting in Sápmi. I heartily recommend it for students and scholars." —Trude Fonneland, The Arctic University Museum of Tromsø

"Barbara Sjoholm's new book takes you on a remarkable journey. What emerges from this insightful study is an important cultural history of the Indigenous Sámi people in northern Finland, Sweden, Norway, and Russia. This book traces how scholars, clergy, and other collectors actively worked to shape how we understand (and misunderstand) the Sámi people and their world. By exploring how the materials crafted by the Sámi have been gathered, studied, and displayed, Sjoholm offers a glimpse into how knowledge has been constructed, controlled, and disseminated over time. People have been writing about the Sámi since the 1500s, but as From Lapland to Sápmidemonstrates, the Sámi culture became a testing ground for emergent sciences like ethnography and archaeology, fields that encouraged participants to gather objects for museums across Europe and beyond. This is a story with important ramifications for the world today." —Samuel J. Redman, author of The Museum: A Short History of Crisis and Resilience and Prophets and Ghosts: The Story of Salvage Anthropology

October 26, 2022

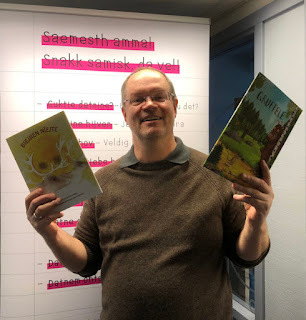

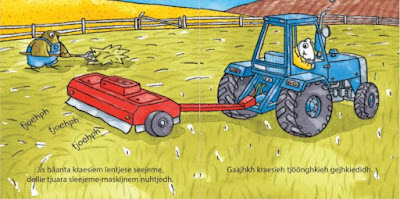

Publishing Children's Books in South Sámi: One Way to Save and Develop a Language

A friend first told me about an article in English by a Norwegian librarian at the Trøndelag county library in Norway. Morten Olsen Haugen is working with the Sámi community to translate and publish more children's books, everything from picture books to YA to audio books, in the south Sámi language.

Morten Olsen Haugen, librarian and publisher

Morten Olsen Haugen, librarian and publisherSouth Sámi is one of the smaller Sámi language groups, with an estimated 600 to 2500 speakers, mostly in Norway (compared to at least 20,000 speakers and readers of North Sámi in Norway, Sweden, and Finland). Although more adults and children now study and speak south Sámi, there have been fewer resources for them.

Until around ten years ago when the Trøndelag county library jumped into publishing. Since then around a hundred books have been published.

According to Morten Olsen Haugen, "While we acknowledge the need to develop indigenous voices and literature, we could not sit and wait for these books to emerge.

"We needed to publish a large quantity of books at a rapid pace. When we started, there were 2-3 new children’s books in southern Saami each year. We’ve published more than 10 each year.

"There is also the matter of language policy here. We want to bring the Saami language outside the traditional areas of their users’ culture. Saami children should be able to use their heart language even when they read – and talk – about pets, football, pirates, princesses, ghosts and monsters."

For readers of Norwegian (Nynorsk), here's a link to one of Haugen's own posts describing the project in greater detail. The images here are taken from that post.

September 12, 2022

By the Fire: Now in Paperback

First published in English translation in 2019, By the Fire, an engaging collection of Sami folktales from Scandinavia illustrated in the early twentieth century, is now available in paperback from the University of Minnesota Press.

These stories, collected by the Danish artist and ethnographer Emilie Demant Hatt (1873–1958) during her travels in the early twentieth century among the nomadic Sami in Swedish Sápmi, grant entry to a fascinating world of wonder and peril, of nature imbued with spirits, and strangers to be outwitted with gumption and craft. This first English publication of By the Fire is at once a significant contribution to the canon of world literature, a unique glimpse into Sami culture, and a testament to the enduring art of storytelling.

July 5, 2022

Climate Justice Panel at the EU-SAMI WEEK

The Markbygden wind farm in Pitea, Sweden/Washington Post

The Markbygden wind farm in Pitea, Sweden/Washington PostIn my previous blog I offered a few impressions from the streamed panels I listened to as part of EU-Sámi Week (June 20-22, 2022) at the European Parliament in Brussels. On Tuesday afternoon, June 21, there was a two-part program on Climate Justicethat I highly recommend watching for better insight into how an Indigenous people are dealing with increasing demands on their traditional lands in the name of green energy and sustainability.

A few days ago (June 29, 2022) the Washington Post published an articleon “the Green Revolution Sweeping Sweden,” detailing the excitement in certain industrial and government sectors about various plans for steel plants and other factories to be sited up in the north of the country, factories that would offer plenty of jobs and also be built and operated using green technology. Often called the “green transition” in the press, these initiatives and others align with Sweden’s admirable goal to be fossil-free by 2045, and to ensure that 100% of the energy used will be renewable. At the same time, the “green transition” tries to reassure us that businesses and individuals will not suffer: Increased growth, often involving global partners, will be fully sustainable and even highly profitable.

On the Climate Justice panel, Mikael Kuhmunen, a reindeer herder and the leader of the Sirges sameby near Jokkmokk, said the “green transition” should instead be called the “black transition.” The recent decision in March, 2022, by the Swedish government to go ahead with granting a mining lease to Jokkmokk Iron Mines AB for the Gallók open pit mine is a bitter blow to reindeer herders and to environmentalists who had hoped that the mining concession would be cancelled. Iron Mines AB is a subsidiary of Beowulf Mining, a UK-based company that has had its eye on Gallók for many years. Many thought that the mine would never be approved because of the steady and increasing opposition.

There is nothing green about this proposed iron ore mine so close to the Lule River, or the many other iron ore, copper and other mines planned for Northern Sweden. Nor is there much that'svery green about the proposed steel mills near Luleå, which will rely for energy on hydropower and a proposed huge wind farm.

Mikael Kuhmunen participated in one of the two panels on Climate Justice held at the EU-Sámi Week. These two panels involved Sámi politicians, activists, and youth organizers, as well as a few non-Sámi politicians from Sweden and Finland and EU bureaucrats, one of whom was Jesús Alquézar Sabadie, a socio-economic analyst, who projected sympathy and understanding for the issues facing the Sámi in the Arctic, and said that most climate policies are based on macro-modeling, and don't take into account human rights and the rights of Indigenous people.

Michael Mann, the EU Special Envoy for Arctic Matters, participated in both panels. He is British and has held various portfolios; his air was polite and politic. He wanted to listen, he often said, while often reminding the Sámi that they shared the same goal (fewer hydrocarbons) and that the Sámi would not get everything they wanted from the EU.

As the panels went on, I often had the feeling that in spite of the expressed desire to work together, the Sámi panelists and the EU representatives were often speaking to different worldviews and in parallel languages. The tone was even and courteous, but the Sámi took issue at times with EU-speak about sustainable growth. In the second panel, Åsa Larsson Blind, currently vice-president of the Saami Council, asked some searching questions about growth and what was meant by the word sustainable. “What are we sustaining?” she asked. “Should we be using this many resources or should we become more efficient with the resources we have?” She side-stepped a suggestion from the EU parliament member from northern Sweden that the Sámi might consider becoming part owners of some of these energy companies, such as LKAB, the giant Swedish state-owned mining company that operates the lucrative mine in Kiruna and has development interests elsewhere in northern Sweden/Sápmi. Such ownership would result in benefit-sharing of profits. Behind such talk was the assumption that northern Sweden is both empty and poor, and that everyone would benefit from the income generated by “green” projects.

Åsa Larsson Blind quietly countered that the Sámi people considered themselves “caretakers” of the land, and their primary responsibility was to protect the land, as they had always done. She spoke of Indigenous knowledge as a benefit to others, that Sámi use of the land had something to teach outsiders. For instance, biodiversity loss tends to be far less in Indigenous lands than in more developed areas.

Just as pointed were the thoughtful words of Eirik Larsen, an Indigenous lawyer and a political advisor to the Norwegian Sámi Parliament. He spoke of the richness of Sámi life and reminded the EU speakers that not everything in life was based on money. Just as importantly he spoke to the issue of consent.

Throughout the text of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), adopted in 2007 by the General Assembly (including all the countries in the EU), the words “free, prior, and informed consent” consistently appear. Of note in the case of land use is Article 32, which states that:

1. Indigenous peoples have the right to determine and develop priorities and strategies for the development or use of their lands or territories and other resources.

2. States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the development, utilization or exploitation of mineral, water or other resources.

Eirik Larsen reminded the EU representatives that “first we talk about consent. And then we talk about sharing benefits.” He also reminded those on the panel that sometimes when the state and Sápmi consulted together, “the answer is no.”

This discussion is taking place at a time when member states of the EU are highly concerned about energy security because of the war of aggression against Ukraine and the sanctions against Russia. Part of the desire for security is not having to depend on unstable states outside the EU for energy supplies but to develop the EU's own resources and to focus on renewable energy. In this calculation, member states like Sweden and Finland are thought to play a significant role. The Arctic is under extreme stress from climate change, including the warming of the polar areas and the destruction of boreal forests to logging and disease. But the lands above the Arctic circle also are rich in minerals, rivers, and less populated areas for wind farms.

If Sápmi didn’t have many things that Europe now wants and needs, there might not have been the impetuous for an EU-Sámi week of discussions open to public viewing. The Sámi, a minority in the Nordic countries and even more a minority in Europe, are important players in Arctic and energy discussions and will become more so in future. The question is whether Indigenous rights and a parallel view of what makes life rich and sustainable will also get a hearing.

And whether the Sámi will find enough support to demanding the right to say “No.”