Barbara Sjoholm's Blog, page 2

June 18, 2025

Women Write About Svalbard: Christiane Ritter, Cecilia Blomdahl, and Line Nagell Ylvisåker

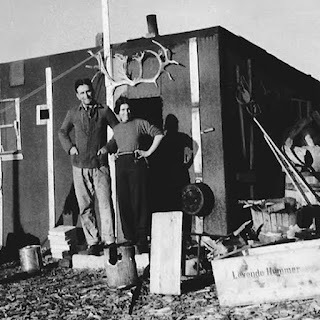

Christiane and Hermann Ritter in front of their house on Svalbard I’ve been dreaming these days about the polar regions, the Arcticin particular. In the midst of attemptingto digest a good deal of difficult news, which seems to fly at us from alldirections but mainly emanates from Washington D.C., I don’t want to forgetabout climate change. The melting glaciers of Greenland, Svalbard, and Antarcticaconcern us all. Long after this sinister administration is gone, we’ll beliving through the consequences of denying scientific research.

Christiane and Hermann Ritter in front of their house on Svalbard I’ve been dreaming these days about the polar regions, the Arcticin particular. In the midst of attemptingto digest a good deal of difficult news, which seems to fly at us from alldirections but mainly emanates from Washington D.C., I don’t want to forgetabout climate change. The melting glaciers of Greenland, Svalbard, and Antarcticaconcern us all. Long after this sinister administration is gone, we’ll beliving through the consequences of denying scientific research. I'm thinking about the environment as I work on my currentproject, a memoir about my travels up in Arctic Norway last summer. But I've also been paying attention to those who have traveled and lived up in the high North. I’ve been researching the Norwegian explorers, FridtjofNansen and Roald Amundsen; the Sámi members of expeditions to Greenlandand Antarctica; Tromsø’s role as an Arctic research center. And then, of course, there’s Svalbard. I visited the archipelago briefly once decades ago when I worked on the Norwegian coastal steamerone summer, and the memory of the polar ice north of Ny Ålesund is still powerful.

Which brings me to two books I’ve recently read, and another I've only read about, written by womenwho lived or are living on Svalbard. Books that couldn’t bemore different in scope, format, and tone, but that taken together say somethingabout the ways in which woman have experienced the North and also projectedthemselves into it.

A Woman in the Polar Night, by Christiane Ritter, isa translation from the German that originally came out in 1938 (in 1954 in England).This short memoir has stayed in print in her native Austria ever since but was aforgotten classic when Pushkin Press reissued it in 2024. It’s the account of ayear that Ritter, then in her early thirties, spent with her husband, Hermann,a naval officer who went to Svalbard on a scientific expedition and stayed tobecome a trapper and hunter. He telegraphed her to come and join him and in1934 she did, leaving behind her teenage daughter and the comforts of life inVienna.

A Woman in the Polar Night, by Christiane Ritter, isa translation from the German that originally came out in 1938 (in 1954 in England).This short memoir has stayed in print in her native Austria ever since but was aforgotten classic when Pushkin Press reissued it in 2024. It’s the account of ayear that Ritter, then in her early thirties, spent with her husband, Hermann,a naval officer who went to Svalbard on a scientific expedition and stayed tobecome a trapper and hunter. He telegraphed her to come and join him and in1934 she did, leaving behind her teenage daughter and the comforts of life inVienna. Ritter tells us almost nothing about that old life. From themoment she arrives, she is fully present in the overwhelming world of Svalbard,which at first shocks her with its emptiness and desolation, even at summer’stail end: “The boundlessly broad foreland, a sea of stone, stones stretching upto the crumbling mountains and down to the crumbling shore, an arid picture ofdeath and decay.”

But as the months progress, her experience changes. Thestove is primitive and sooty; the menu relies too heavily on oily seal meat,the polar night descends unmercifully. While the Aurora and the stars whirlaround dark sky, the shack can feel alternately cozy and claustrophobic. Ritter feels at times small and afraid, especially when left for days alone in thecabin she and Hermann share with a younger Norwegian, Karl, when the men areout hunting. But if her descriptions of the effort of daily existence areprecise and sometimes humorous, her writing about the mountains, fjords andespecially the ice, the snow, and the changing light as autumn becomes winterand winter becomes spring begins at times to rise to an exultation that wecommonly associate with saints in the grip of an ecstatic vision of God and theuniverse. At one point Ritter displays hints of an Arctic madness—she becomes,Karl’s brief formulation, rar, the Norwegian word for “strange.”

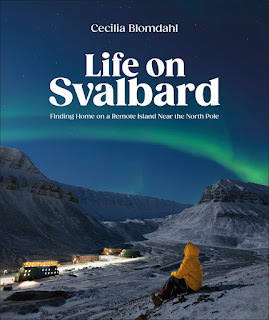

Swedish photographer Cecilia Blomdahl’s 2024 coffee table book, Life on Svalbard, couldn’t be more different in scope, format, and mood. AWoman in the Polar Night is austere and poetic; Christiane Ritter relies onher pen to create indelible imagery. There are only a few sketches and blackand white photographs. She’s modest to a fault; we could wish we knew moreabout her. What kind of art does she make and how does she support herself? Whyis her husband in Svalbard and is he ever coming home? What does she thinkabout the political situation in Central Europe and the rise of National Socialism?

Blomdahl inhabits another world entirely, that of a contentcreator across multiple social media channels. She’s on Instagram, she’s onTik-Tok, she’s on Facebook, and she’s on YouTube, where she’s made 500 videosof her life near the main town of Longyearbyen. One of them from a few years ago,explaining “THIS is why I live on a remote Arctic island with 3000 people and polar bears,” has garnered over 4 million views. Blomdahl cameto Svalbard in 2016 to work in the hospitality field. She immediately took to the cold and extremes of light and dark overthe course of the year. With her Norwegian boyfriend, initially a cook at thesame hotel, she moved a short way outside Longyearbyen to a cabin with a viewof seven glaciers. From there she discovered photography as a way ofcommunicating with hundreds of thousands of people across the globe, who alsodream of cold, remote places, but perhaps don’t actually want to go there. Theywould rather watch Blomdahl in snowsuits on her snowmobile, or in her longunderwear reading a book, or in her swimsuit braving an icy dip. She’s oftenphotographed from behind, staring at the landscape, her brown hairflowing, or sitting on the porch or inside the cabin, with a steaming cup ofcoffee, demonstrating hygge in the midst of wilderness. Svalbard isthere, in full view, but as she says in one video, “Svalbard is a feeling, it’sa lifestyle, not just a place.” Her viewers write comments praising herpositivity. They seem to love the combination of gentle reality show superimposedon a harsh but stunning northern landscape.

Life on Svalbard has many gorgeous photos but the Englishtext is oddly flat. I believe she writes in English much as she speaks, withonly a slight Swedish accent, using pedestrian phrases that come from thetourist industry. Blomdahl wants to convey the ineffable, but the words that come out onlygrasp vaguely in that direction. There is much that is “breathtaking” or that“takes your breath away.” And although there are also possibledangers—avalanches, walruses, polar bears—there are many domestic pleasures. Cecilieand Christoffer have GPS to find their way to even more remote cabins on theisland of Spitzbergen. They get shipments from Ikea to remodel their kitchen. Theyvisit with friends and drink coffee. They play with their dog Grim. Withsnowmobiles, cars, boats, wi-fi, and their vast audience, they are living aEuropean lifestyle in a place that once was only for the toughest-minded survivalist.

Life on Svalbard has many gorgeous photos but the Englishtext is oddly flat. I believe she writes in English much as she speaks, withonly a slight Swedish accent, using pedestrian phrases that come from thetourist industry. Blomdahl wants to convey the ineffable, but the words that come out onlygrasp vaguely in that direction. There is much that is “breathtaking” or that“takes your breath away.” And although there are also possibledangers—avalanches, walruses, polar bears—there are many domestic pleasures. Cecilieand Christoffer have GPS to find their way to even more remote cabins on theisland of Spitzbergen. They get shipments from Ikea to remodel their kitchen. Theyvisit with friends and drink coffee. They play with their dog Grim. Withsnowmobiles, cars, boats, wi-fi, and their vast audience, they are living aEuropean lifestyle in a place that once was only for the toughest-minded survivalist.

Although Svalbard is one of the places most at risk in thesetimes of climate change, and although much of the research that goes on inLongyearbyen and farther north at the research station in Ny Ålesund has to do with rapidlymelting glaciers and warming seas, there’s nothing about that inconvenienttruth in Life on Svalbard. We don’t learn much about the archipelago’shistory as a whaling station or its mining operations, or about its connection withNorway and its political structure. It’s an innocuous book, with gloriousvisuals, but unreal somehow. Blomdahl mentions the presence of researchers butdoesn’t explain what they are studying. The couple’s friends may also be fromthe hospitality field—after all, you have to have a job or an income to beallowed to stay in Svalbard—but mostly they are engaged in leisure activities.Don’t get me wrong, Cecilia Blomdahl’s photographs are striking, but they areoddly detached from the lives of most people on the archipelago.

C hristiane Ritter’s book was written before an understandingof the effects of climate change on glaciers, but for Cecilia Blomdahl there’sreally no excuse. After all, in 2015 a devastating avalanche hitLongyearbyen during a strong winter storm. Houses were damaged, people wereevacuated temporarily, and one man was killed. The story of the avalanche andits aftermath are told in a 2020 book My World is Melting – Living withClimate Change in Svalbard, by the Norwegian journalist and longtimeSvalbard resident, Line NagellYlvisåker, who is also the editor of Longyearbyen’s newspaper. Although thebook was translated to English in 2022, that edition is only available onSvalbard itself. In lieu of my own take on the book, I offer for now a review I foundonline by a Dutch meteorologist, Daan van den Broek, who isbased in Finland and travels often to Svalbard.

hristiane Ritter’s book was written before an understandingof the effects of climate change on glaciers, but for Cecilia Blomdahl there’sreally no excuse. After all, in 2015 a devastating avalanche hitLongyearbyen during a strong winter storm. Houses were damaged, people wereevacuated temporarily, and one man was killed. The story of the avalanche andits aftermath are told in a 2020 book My World is Melting – Living withClimate Change in Svalbard, by the Norwegian journalist and longtimeSvalbard resident, Line NagellYlvisåker, who is also the editor of Longyearbyen’s newspaper. Although thebook was translated to English in 2022, that edition is only available onSvalbard itself. In lieu of my own take on the book, I offer for now a review I foundonline by a Dutch meteorologist, Daan van den Broek, who isbased in Finland and travels often to Svalbard.

May 7, 2025

The Agency of Sea Ice: Sohvi Kangasluoma Overwinters in a Sailboat in Greenland

In 1897 Fridtjof Nansen published Farthest North, hisnarrative about the three years he spent in the Arctic, part of it on thefamous ship, the Fram, and part of it attempting to sledge to the NorthPole with one companion from the ship and being turned back by the ice to facea harrowing fifteen months before being rescued on Franz Josef Land. I readthis book quite recently and still am thinking about the amazing factthat he, all his companions on the ship, and the Fram itself survivedthree years of polar weather and challenges. They didn’t reach the pole butthey did get within a few degrees. Some of the most entrancing sections of thebook are the descriptions of the cozy interior of the ship; locked into the iceand drifting west in the direction of Svalbard, the expedition team read books,ate nice meals with desserts, and played cards, while the wind howled and thesnow fell outside.

Nansen studied to become a marine biologist before he becamea polar hero and later a statesman with a side line in oceanography. In theintroduction to Farthest North he lays out a short history of attemptsto reach the North Pole by ship, and the many disasters. He explains his owntheory of ocean currents that run west from Siberia to Greenland and how they couldhelp, not hinder a ship in an expedition to the Pole.

In memorable and prescient words, he writes, “I believethat if we pay attention to the actually existent forces of nature, and seek towork with and not against them, we shall thus find the safest andeasiest method of reaching the Pole.”

Sohvi Kangasluoma with her dog on the ice

Sohvi Kangasluoma with her dog on the iceThe other day I had cause to remember those words, when I readan article in the HighNorth News (April 30, 2025) about Dr. Sohvi Kangasluoma, a youngwoman scientist from Finland who’s taken some of Nansen’s ideas further. Kangasluoma, a post-doc at the Arctic Centre at the University of Lapland, livesand works with her partner Juho Karhu in their sailboat. Lastsummer the couple transited the Northwest Passage from Alaska to Greenland to studythe movement of ice. In the winter of 2024-2025 they embedded the boat in packice off the east coast of Greenland.

Kangasluoma’s dissertation is titled Understanding Arcticoil and gas: Entanglements of gender, emotions and environment (and can bedownloaded here).In the High North article she discusses the ways that the Arctic iscurrently viewed as a geopolitical prize to be fought over, Kangasluoma has pointedout that sea ice “is approached as something that just is and melts. Butit is anything but a passive and dead thing; it is very much alive, and it hasagency of its own."

Like other researchers influenced by feminist and ecologicalviews of nature, Sohvi Kangasluoma, looked beyond the sea as only a place toextract wealth, whether in the form of fish, minerals, or oil and natural gas,an enormous site of geopolitical greed and political conflict. She researchedthe Arctic seas with an eye to the non-human. "We tend to have this veryanthropocentric way of thinking. Humans need a shift in knowledge. Humans arenot alone here; there are so many other actors as well. This is, of course,already present in many Indigenous ontologies and ways of life, which we needto start listening to."

The article has a link to a video called “Turning Our Boatinto an Igloo.” The YouTubechannel, Alluring Arctic Sailing, has other videos equally fascinating. It's maintained by Juho Karhu,who has a scientific background as well and contributes to voluntary researchprojects. His voice and manner are incredibly calm, no matter whatseems to be happening on the ice or how hard the wind is blowing.

April 3, 2025

Sápmi Lands Threatened by EU’s Approval of Raw Materials Strategic Projects

News that the mining projects Talga Graphite in Nunasvaara,LKAB ReeMap in Malmberget, and LKAB Per Geijer in Kiruna were part of a mass approval on March 24, 2025by the European Commission was a shock to the Sámi Council, which has issued astrong statement.Other sites are located in the Sámi part of Finland. The mining projects ontraditional Sámi territory, some of 47 “strategic projects” around Europe, arethe result the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act on May 23, 2024, aimed at reducingsupply chain vulnerabilities. Many of the areas to be mined can also producethe raw materials required in a conversion to so-called green energy.

News that the mining projects Talga Graphite in Nunasvaara,LKAB ReeMap in Malmberget, and LKAB Per Geijer in Kiruna were part of a mass approval on March 24, 2025by the European Commission was a shock to the Sámi Council, which has issued astrong statement.Other sites are located in the Sámi part of Finland. The mining projects ontraditional Sámi territory, some of 47 “strategic projects” around Europe, arethe result the EU’s Critical Raw Materials Act on May 23, 2024, aimed at reducingsupply chain vulnerabilities. Many of the areas to be mined can also producethe raw materials required in a conversion to so-called green energy. The Sámi Council, along with the Sámi parliaments in theNordic countries have long made it clear that they lack the legal staff andfunding to tackle the impacts of each proposed project on the environment andSámi culture, a culture closely interwoven with the landscape. Internationalcorporations had already been expanding in Sápmi. The Australian company, Talga, for instance, whichplans to mine graphite in the winter reindeer grazing lands around Vittangi,near Kiruna, has long fought court battles with the Talma Sámi siida. Now,thanks to the fast-tracked status of the project given by the EU, the projectcan move ahead without the Sámi being likely to mount an effective defense.

“The EU is promoting the exploitation of minerals thatcontribute to human rights abuses within the EU,” Per-Olof Nutti, president ofthe Saami Council said. “This is a direct violation of our rights as the onlyrecognized Indigenous People within the EU.”

March 31, 2025

Siri Broch Johansen Awarded Ibsen Prize

Siri Broch JohansenThe Ibsen Prize is Norway's only drama award and considered one of the most prestigious international drama prizes. Last week, on March 20 (Ibsen's birthday), in a first for a Sámi author, Siri Broch Johansen was awarded the Ibsen Prize for her play, Per Hansen: A Faithful Man/oskkáldas almmái which premiered in October, 2024 at Norway's traveling theater, Riksteatret.

Siri Broch JohansenThe Ibsen Prize is Norway's only drama award and considered one of the most prestigious international drama prizes. Last week, on March 20 (Ibsen's birthday), in a first for a Sámi author, Siri Broch Johansen was awarded the Ibsen Prize for her play, Per Hansen: A Faithful Man/oskkáldas almmái which premiered in October, 2024 at Norway's traveling theater, Riksteatret.Per Hansen: A Faithful Man is described on the theater's website as “a juicy, humorous, steamyerotic, and honest piece. It's about adult love, complex life choices, andenduring this life.” A rave review on NRK celebrates how the two characters, both Sámi, explore a relationship outside marriage, with all the heartbreak and loneliness that can involve.

Much of the action takes place on a sofa as the actors talk about sex, desire, and what's possible in explicit terms. From the reviews, it seems that Norway has never seen Sámi people through this lens before--as ordinary, not particularly exotic human beings--yet still Sámi for all that.

Siri Broch Johansen is, in addition to an author of several books, a language teacher and singer, living in the Tana municipality in East Finnmark/Sápmi. I know her work from her biography of the Sámi activist Elsa Laula Renberg, published in 2015.

[image error]

February 9, 2025

Barbara Sjoholm and Kaja Gjelde-Bennett talk about The Reindeer of Chinese Gardens

A new interview about The Reindeer of Chinese Gardens with Sámi-American Ph.D. student Kaja Gjelde-Bennett. Kaja and I talk about immigration to the Pacific Northwest by Chinese, Norwegian, and Sámi at the turn of the 19th century and about the setting of the novel in Port Townsend, Washington. Kaja will be leading a book club discussion of the novel on February 27, 2025 at 6 pm. Sign up through Nordiska.

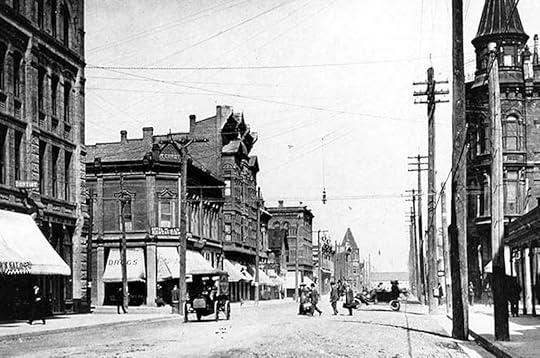

Water Street, Port Townsend, WA 1908

Water Street, Port Townsend, WA 1908

February 2, 2025

Upcoming Events for Reindeer of Chinese Gardens

My new historical novel, The Reindeer of Chinese Gardens, now feels officially launched, with some upcoming events scheduled for February and March.

My new historical novel, The Reindeer of Chinese Gardens, now feels officially launched, with some upcoming events scheduled for February and March.On Thursday, February 20, I'll be doing a reading from the novel in the Carnegie Room of the Port Townsend Library. It seems like a perfect place, since the stacks of maritime titles are nearby, and were an important source for me while writing the book.

The library on Lawrence Street isn't far from where Dagny and her family and friends lived in the Uptown district of Port Townsend in the 1890s.

After the reading, I'll be selling and signing books. You can also purchase copies in the historic Aldrich's market (founded in 1895), also on Lawrence Street, and at our local bookstore, Imprint Bookshop, down on Water Street, in the heart of Port Townsend. One of my favorite bookstores in the Pacific Northwest, Port Book and News in Port Angeles, also has copies.

Later in February, I'll be attending an online book club meeting about The Reindeer of Chinese Gardens, sponsored by the fantastic Nordiska shop in historic Poulsbo, Washington. Poulsbo is well-known for its Scandinavian roots, but it's not as well-known that a significant number of Sámi immigrants and their descendants also called and call Poulsbo home. The wonderful moderator of the book club, which has been going for three years, is Kaja Gjelde-Bennett, who herself has Sámi family connections to Poulsbo. She is currently living in New Mexico and pursuing a Ph.D. after having been awarded a master's in Indigenous Studies at the Arctic University of Norway in Tromsø. The Nordiska is a great spot to shop for all things Nordic, and carries a selection of Scandinavian books as well. During February The Reindeer of Chinese Gardens can be purchased in person or online for a 15% discount.

And finally, a heads up about an event on March 20 at the Nordic Museum in Ballard, a neighborhood of Seattle. I'm really pleased to be speaking at the Nordic again and in Ballard, where a good deal of the second half of the novel takes place in 1906-1907. I'm also delighted to be in conversation with Amy Swanson King. Amy is a journalist and past president of the Pacific Sámi Searvi. She's currently a Ph.D. student at the University of Washington, studying issues impacting the Sámi, American Sámi and descendants, Indigenous diaspora and language revitalization. Amy and I go back a few years, and in 2023 had a chance to discuss an earlier book of mine, From Lapland to Sápmi on Crossing North, a podcast sponsored by the University of Washington's Scandinavian Department.

Velkommen to any and all of these events!

January 7, 2025

The Reindeer of Chinese Gardens, my new historical novel

Sjoholm is a gifted storyteller, eloquent on the subjectof Sámi prejudice and the poignant dilemma for all immigrants: Make a life foryourself in this new world, or surrender to the emotional pull of the oldcountry? And while Dagny has her own demons, she ends up being not just asurvivor, but a humane model for all of us. An engrossing novel that features a memorably strong,vibrant female character.

Kirkus Reviews

Through the journals of Dagny Bergland, Barbara Sjoholm has givenvoice to the challenges of immigration from a variety of viewpoints –Norwegian, Chinese, Sami. Their stories are complex, touching, sometimestragic. It is above all, a story of America and what it means to be assimilatedinto American culture and geography.

MarleneWisuri, Chair, Sami Cultural Center of North America

I’m thrilled to announce that my new historical novel, TheReindeer of Chinese Gardens, is now available in print and ebookeditions. I had the idea for a novel set in Port Townsend, where I live, manyyears ago, but it took a long time to come to fruition. It involved a lot ofresearch into not only this city’s boom-and-bust history in the late 1800s, butalso research on the “Reindeer Rescue” expedition that brought Sámi fromLapland to Seattle, Port Townsend, and Alaska in 1898, in an ill-fated attemptto supply the Yukon Gold Rush miners with food by reindeer. I also exploredPort Townsend’s Chinese district, Norwegian-American newspapers, seafaring inthe waning Age of Sail, Seattle’s history, especially the Ballardneighborhood—and much more. No wonder that with all this research, in additionto a number of other books and translations I published over the last decade,that The Reindeer of Chinese Gardens took me over twelve years tocomplete.

Norwegian-born Dagny Bergland and her husband arrive inturn-of-the-century Port Townsend, Washington after years of sailing theirmerchant ship around the globe. They’re just in time for the Yukon Gold Rushand the arrival of a group of Sámi reindeer herders from Lapland on their wayto Alaska to supply the ill-prepared miners. Dagny’s journals, beginning in1897, tell a fresh and riveting history of the Pacific Northwest and itsimmigrants. A novel of friendship, love, loss, and motherhood, The Reindeerof Chinese Gardens is the story of a remarkable woman who learns to steer anew course in a new country.

Although the official publication day is February 1, you canfind it on sale now at Amazon, in printand as an ebook, or fromother vendors via Draft2Digital,such as Apple, Kobo, Smashwords, and Barnes & Noble. It is also availableor can be ordered from brick-and-mortar independent bookstores or online frombookshop.org.

I’ll be giving a reading at the Port Townsend LibraryThursday evening at 6pm on February 20. I’ll also be in conversation with AmySwanson King of the Pacific Sámi Searvi at the Nordic Museum in Seattle onThursday, March 20. Amy and I previously had a great talk for Crossing North about my previous book, From Lapland to Sapmi.

Barbara Sjoholm and Amy Swanson King, Seattle, Nov 2023

Barbara Sjoholm and Amy Swanson King, Seattle, Nov 2023

November 18, 2024

Helene Uri's Novel Clearing Out, now in paperback

Thrilled to announce that Clearing Out, a fantastic novel by Norwegian author Helene Uri, is now available in paperback from the University of Minnesota Press. I had the joy of translating it some years ago, and it's one of those books that has really stayed with me. It's not just another book about the Sami by an outsider; nor is it a book by someone who has grown up in a Sami family. It's a layered story of a novelist very like Helene Uri who is writing a novel about a linguist who goes north to do language research, a novelist who in the course of writing this novel finds out that she has Sami background. This is not unusual in Norway, especially for those whose relatives once lived in Northern Norway. As readers we learn a lot, but in a natural and absorbing way, from both women's experiences--Helene's and her character Elinor's.

Nadia Christensen Prize for translation from the American-Scandinavian Foundation

Here's what the publishers write about it, in greater detail, followed by praise from two writers who have also spent time up in the North, Rebecca Dinnerstein and Vendala Vida.

Inspired by Helene Uri’s own journey into her family’s ancestry, Clearing Out, an emotionally resonant novel by one of Norway’s most celebrated authors, tells two intertwining stories. A novelist, named Helene, is living in Oslo with her husband and children and contemplating her new protagonist, Ellinor Smidt—a language researcher, divorced and in her late thirties, with a doctorate but no steady job.

An unexpected call from a distant relative reveals that Helene’s grandfather, Nicolai Nilsen, was the son of a coastal (sjø) Sami fisherman—something no one in her family ever talked about. Uncertain how to weave this new knowledge into who she believes she is, Helene continues to write her novel, in which her heroine Ellinor travels to Finnmark in the far north to study the dying languages of the Sami families there. What Ellinor finds among the Sami people she meets is a culture little known in her own world; she discovers history richer and more alluring than rumor and a connection charged with mystery and promise. Through her persistence in approaching an elderly Sami activist, and her relationship with a local Sami man, Ellinor confronts a rift that has existed between two families for generations.

Intricate and beautifully constructed, Clearing Out offers a solemn reflection on how identities, like families, are formed and fractured and recovered as stories are told. In its depiction of the forgotten and the fiercely held memories among the Sea (sjø) Sami of northern Norway, the novel is a powerful statement on what is lost, and what remains in reach, in the character and composition of contemporary life.

"Lyrical, brave, and luminous, Clearing Out offers the overdue translation of a signature Norwegian voice into rapturous English."—Rebecca Dinerstein, author of The Sunlit Night

November 8, 2024

A Skolt Sámi Folktale from Neiden

The Guoddan

Mother Ondrej had come from Suonjel [Suonjel, or Suõ’nn’jel, wasone of seven Skolt Sámi sijdds; Suõ’nn’jel is on the Russian side of the border with Norway.] Herchildhood home was Vilggis-vandet. She told me that once as a girl she went tosee the wild reindeer pit traps there. The pits were between two lakes, as isthe custom.

As she was walking and looking atthe pit traps, she heard a faint cry from up in the sky, and then it sounded abit stronger, and then she heard the crying coming closer. Then she saw afearfully large bird coming. It flew with the claws of both feet curledtogether, and in between the feet hung a young Russian woman crying. The birddropped her on the ground under a tree; it perched in the tree itself, and thetree began to sway this way and that, because the bird was as big as a reindeerox. The Russian woman said to the young Skolt girl, “You must tie yourself to apine tree or the bird will take you.” The bird could have left the Russianwoman, but it was better if it flew away with her since it had already almostcrushed her to death.

But when the bird noticed that theywere talking, it shook its head, and the feathers on its neck all sounded likebells, clanging so that they could no longer hear to keep talking.

The bird perchedin the tree for a while. It tried to attack the Skolt girl, but it only got thehat off her head, then it settled in the tree again. It perched there a while,and then it took hold of her again. But as she was tied to the pine tree, itcould not take her this time either. Still the bird grabbed her hair and herskin along with it. The girl fainted and fell to the ground. When she woke upagain, the bird was about to fly off. The Russian woman was again between itsclaws, crying, and then it flew westward. The Russian woman's cry was heard fora very long time in the air. Then that cry also disappeared

Such a bird was formerly called aguoddan. The guoddan was also the kind of bird that an evil man set on anotherman. From that comes the Sámi proverb: “He screams as though he’s in aguoddan's claw.”

MotherOndrej, to whom this happened, had come to Neiden and married. She had regainedsome hair, but it wasn’t much. And there were claw marks on her neck.

(Translation copyright, Barbara Sjoholm, 2024)

Isak Saba, politician, teacher, folklorist

Isak Saba, politician, teacher, folkloristThis Skolt Sámi story was transcribed in 1918 or 1919 byIsak Saba in the village of Neiden, Norway. The storyteller was either Ivan orNikolai Ondrevitsj, the sons of “Mother Ondrej,” Marie Avdatje Vasilevna. It’sone of many tales that Saba collected in Neiden withfinancial support from the Norwegian Folklore Archives in Oslo. Saba also collectedother tales about animals, about the hidden folk, andabout noaidis, revenants, and the robbers from “the East,” called Chudes. Saba’soriginal transcriptions and translations into Norwegian of this material becamepart of J.K. Qvigstad’s four volume work, Lappiske eventyr og sagn (SámiFolktales and Legends), published in 1927-29.

My translation from Norwegian is part of a selectedcollection of around three hundred tales collected by J.K. Qvigstad and IsakSaba, to be published in late 2025 by the University of Minnesota Press.

May 23, 2023

Norwegian Parliament Votes to Refer to the Sámi as Indigenous in the Constitution

On May 15, 2023, according to NRK, the Norwegian Parliament voted to amend their Constitution and refer to the Sámi people in Norway as Indigenous for the first time. 147 representatives voted for the proposal, while 22 representatives voted against, with the right-wing Progress Party (Fremskrittspartiet) opposing the change. "It is of great symbolic importance," said the head of the Labor Party. "By recognizing the Sámi as an Indigenous people in the Constitution, you put a permanent end to the policy of Norwegianization."

Norwegianization was the longtime policy of the governmentfrom around 1880 to 1960 with the intention of assimilating the Sámi into thedominant society. While the change in status in the Constitution is welcome andnecessary, there are those in Norway who are still ambivalent about the use ofthe word Indigenous or urfolk (original people) for the Sámi.

Someone I know in Norway who is currently reading my latestbook From Lapland to Sápmi, wrote me to say they were enjoying it. Theyadded something to the effect that the Sámi were not actually Indigenous, sincethey arrived in Scandinavia after people were already living there: “So theyare not an aboriginal people as such.”

I don’t know all the ins and outs of the debates about “whocame first,” and I have consciously stayed out of discussions on this topic. Ido know, however, that the debate about who are the first inhabitants of Sápmi,although sometimes framed in a scientific way and buttressed by DNA data andother evidence, has been and is still employed by the dominant population inScandinavia to prove that the Sámi claims to territory and natural resourcesare bogus and self-serving.

The period of Sámi history I’m most familiar with is the late 19th century and the 20th century, a time connected with “Lappology” and Racial Biology, but also a time of growing Sámi political resistance and cultural renaissance. During the last half of the 20th century the term “Indigenous” was first claimed by certain Sámi groups as a means of finding connection with and support from other Indigenous people around the globe. This term spread in Sámi society and, although initially resisted by individuals and governments in the Nordic countries, it gradually was adopted in its basic outlines and is now generally accepted. The Sámi were politically recognized as an Indigenous group in Norway in 1987 with the Sámi Act, and again in 1990 when Norway signed the UN’s ILO Convention No. 169 concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries.

For my part, when questions of indigenity come aroundthe Sámi, I’ve often referred back to the fact sheet,“Who are indigenous peoples?” put out by the United Nations Permanent Forum onIndigenous Issues. The UN emphasizes they do not have an official definitionof “Indigenous,” given the diversity of the 370 million Indigenous peoplespread across 70 countries worldwide. Instead they offer a modernunderstanding of the term, based on the following: • Self- identification asindigenous peoples at the individual level and accepted by the community as theirmember. • Historicalcontinuity with pre-colonial and/or pre-settler societies • Strong linkto territories and surrounding natural resources • Distinctsocial, economic or political systems • Distinctlanguage, culture and beliefs • Formnon-dominant groups of society • Resolve to maintain and reproduce their ancestral environmentsand systems as distinctive peoples and communities. Allof these criteria the Sámi meet. I’m especially struck by the last item in thelist: “Resolve to maintain and reproduce their ancestral environments andsystems as distinctive peoples and communities.” Whywaste time debating who came first and instead celebrate the Sámi for this stubbornand creative resolve in the face of centuries of territorial dispossession andcultural racism?