Randal Rauser's Blog, page 96

July 18, 2018

Are theological theories falsifiable?

There is a popular, but altogether mistaken idea that scientific theories differ from theological (or philosophical) ones in that the former can be falsified but the latter cannot. The popularity of this idea can perhaps be traced to the enduring influence of Antony Flew’s parable of the invisible gardener. But it’s flatly wrong. But the way it is wrong may surprise you.

Let’s start by getting our definitions straight. A “theory” is an over-arching explanatory framework for a range of facts. For example, the forensic investigator seeks to develop a theory to account for all the aspects of a crime scene (the facts). Likewise, a scientist seeks to develop a theory to account for all the aspects of some natural phenomena.

In a similar manner, the theologian seeks to develop a theory to account for all the aspects of some theological phenomena. Some examples of theological theories are Anselm’s satisfaction theory of atonement, the Kenotic theory of the incarnation, and the transubstantiation theory of the Eucharist. (The range of data that these particular theological theories seek to explain include data from scripture, tradition, and personal and corporate experience.)

Whether the theory in question is in forensics, natural science, or theology, it is mistaken to think it is ever falsified, except perhaps in exceptional cases. Rather, what happens (or what almost always happens) is that some recalcitrant datum is identified. Assuming the datum is confirmed, the defender of the theory must make a choice: abandon the theory or modify the theory to accommodate the datum.

Imagine, by analogy, that you have an accident in a car. In almost all cases, the car can, in principle, be repaired. The simple question is this: how much are you willing to pay to repair the car? By analogy, the worse the accident, the more serious the recalcitrant data. Just as you need to consider how much you’re willing to pay to repair the car, so you need to consider just how much you’re willing to modify to save the theory. And just as there comes a point where a car is no longer worth repairing, so there comes a time when a theory is no longer worth saving. That time comes when it fails to do what it was originally proposed to do: that is, explain things.

To sum up, theories are regularly proposed in many fields (e.g. forensic science, natural science, theology) and a particular theory can in principle be modified interminably to accommodate ever more recalcitrant facts. But at some point, the theory is no longer worth “keeping on the road”. On that day, it is not falsified: rather, it is merely abandoned on the side of the road.

The post Are theological theories falsifiable? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

July 17, 2018

On Worthwhile Conversation

Last week I wrote an article for my blog on the value of conversation with others, even when your interlocutor is not particularly open-minded. I rewrote the article for Strange Notions and it was just posted this morning. Feel free to join the conversation: even if you aren’t open to my thesis, I’m sure it will still be a worthwhile exchange!

The post On Worthwhile Conversation appeared first on Randal Rauser.

If Jesus has not been raised, is our faith in vain?

Back in November, 2017, I posted a survey on Twitter asking if Christianity requires the historical resurrection of Jesus. A couple days ago, I posted a similar survey with a few notable differences. First, while the original survey was directed to everyone, this survey was targeted at Christians; second, while the original survey only had two options, the new survey had four. You can see the results from the 2017 survey as well as my explanation for how/why some Christians believe the resurrection is not necessary by clicking my article “Does Christianity need a resurrected Jesus?”

And here are the new survey results:

A survey for Christians:

If you became convinced that the bones of Jesus had been discovered in an ossuary just outside Jerusalem, would you renounce Christianity as false?

— Tentative Apologist (@RandalRauser) July 16, 2018

The post If Jesus has not been raised, is our faith in vain? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

July 15, 2018

Puritans at the Cinema

Let me begin with this tweet I came across yesterday from Sean McDowell:

A for Ant-Man and the Wasp: fun, creative, and clean. pic.twitter.com/QAyW5EaWoG

— Sean McDowell (@Sean_McDowell) July 14, 2018

Fun? Check! Creative? Check! Clean? Check!

I know what “fun” and “creative” are. But what does McDowell mean when he says “clean”? Presumably, he means something like this: no sex, nudity or profanity and only minimal (i.e. cartoonish, without blood) violence.

I wouldn’t have a problem with that if McDowell had added something like “Great movie for the kids!” After all, I too am a parent who seeks to be sensitive about what my child is exposed to. (Though now that she is 16, that isn’t the concern it once was.) And thus, over the years I have benefited greatly from the clear summaries of film content at Kids in Mind and Commonsense Media (and also the user-driven reviews at IMDB.com). For example, did you know that Kids in Mind ranks the new Mr. Rogers documentary (Won’t You Be My Neighbor?) as having more sex/nudity than Dwayne Johnson’s new blockbuster Skycraper? Thus, if you’re especially sensitive to sex/nudity, don’t take the tots to Mr. Rogers! (That said, the doc still only scores a lowly 3/10.)

But McDowell didn’t add that disclaimer. In other words, he didn’t specify that it was a review with kids in mind. This leads me to believe that he considers “cleanliness” (i.e. low levels of sex, nudity, violence, and profanity) as an intrinsic value irrespective of the audience.

And if that doesn’t describe McDowell himself, it certainly does describe many Christians who do retain this kind of puritanical sensibility.

Ironically, this Leave it to Beaver puritanical mindset has nothing to do with the Bible which is packed with sex, violence, and a surprising range of profane language (language which is often softened by translators).

It also is a ridiculous means of selecting moral films. For example, by this crude metric, Schindler’s List is not clean since it depicts full frontal male and female nudity, a couple brief sex scenes, sickening levels of violence and human degradation, and a moderate level of profane language.

I’m currently mid-way through Ken Burns excellent new documentary series The Vietnam War. At one point in the series, a journalist recollects that by 1965 the US military had taken to counting dead bodies as a means of judging the success of the war effort. It was an altogether crude and deeply misleading means to measure success in South Vietnam. Nonetheless, the journalist observed drily, when you can’t measure what counts, you count what you can measure.

That sober observation might equally be applied to puritanical Christians who think simply counting up how many f-bombs are dropped and whether blood is split or genitals are shown is an effective way of judging the moral fiber of a film. For individuals like this, it is easier to have a checklist of puritanical offense than to engage the sophisticated themes of a morally complex and nuanced cinematic universe. Again, when you can’t measure what counts, you count what you can measure.

I have discussed these themes on several occasions in the past. See, for example, my articles “How many ‘F’ words in a film is TOO many?” and “Finding Jesus at the movies, but not in the Jesus movies“.

The post Puritans at the Cinema appeared first on Randal Rauser.

July 13, 2018

Is the psychopath morally responsible for his actions?

This article picks up the discussion of my recently-published article “Shrewd as Snakes: The Christian and the Psychopath.” In this article, I will begin with two intriguing quotes from John Henry Browne, the attorney who defended notorious serial killer and clinical psychopath Ted Bundy:

“Ted was the only person in my forty years of being a lawyer that I would say that he was absolutely born evil. This is really the only person, after representing thousands of clients in forty years, that would say that about.”

“I didn’t want to believe people were born evil, but I came to the conclusion that Ted was…. He had this energy about him that was clearly deceptive, very sociopathic.”

Two things intrigue me about Mr. Browne’s observations.

First, Browne skirts the oft-blurred distinction between immorality and amorality. Was Bundy immoral and thus, “born evil”? Or was he amoral in the sense of being wholly unable himself to grasp moral value and obligation? And if the latter, should we speak of him in the categories of good/evil at all? Or should we instead think of his actions in terms of the amoral categories we reserve for non-human predators? It makes no sense to project a moral agent in the blank stare of the grizzly or great white shark right before they strike. Is the psychopath like this?

Second, Browne clearly sees Bundy’s personality disorder as something beyond his ability to control. Whether he was born evil or amoral, his lack of moral goodness seems innate and beyond his capacity to change.

What do you think? Should we describe the psychopath in terms of good and evil? Or do they possess an amoral character which altogether defies standard moral categorization? And what does this do for their moral culpability?

The post Is the psychopath morally responsible for his actions? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

July 12, 2018

When is an apologetic dialogue no longer worth pursuing?

Yesterday, I came across this tweet by Christian apologist Max Andrews courtesy of a retweet by Chad at Truthbomb Apologetics:

When dialoguing with your interlocutor, ask them, “What must obtain so that your position be changed or that you’re convinced of my position?” If they fail to present conditions or claim that nothing will, discard the conversation and neglect the casting of pearls before swine.

— ??? ??????? (@iAmMax_A) July 11, 2018

The goal, presumably, is to focus on conversations that are likely to be “productive”. In this article, I’d like to state briefly why I disagree with Andrews.

Apologetics and Evangelism

Before I get to disagreement, I’d like to set the stage by stating something of my views on apologetics and evangelism. Andrews frames his topic as “dialoguing with your interlocutor.” Since he is an apologist, I assume he is focused primarily here on apologetic reasoning with non-Christians.

With that in mind, let’s be clear that apologetics to non-Christians is a form of evangelism (or, if you prefer, pre-evangelism). While “evangelism” might seem like a fancy word, it refers simply to the practice of sharing your convictions with others in a clear and winsome manner to the end that they too may come to hold those convictions.

Based on that definition, it should be clear that whenever you value a truth claim and you value people who don’t hold that truth claim, you should want to persuade those people to hold that belief. In other words, you should be committed to apologetics/evangelism. This is even more important when the truth claim is on a matter of monumental importance, such as with the truth of Christianity.

Critiquing the Tweet

Now back to the tweet. Andrews claims that if people fail to provide conditions under which they would change their mind, you should abort (or as he says, “discard”) the conversation as nothing more than casting “pearls before swine.”

Does have an open mind require you to know when it would change?

First up, Andrews, assumes that having an open mind entails having an ability to state the conditions under which one would reject one’s belief. But I see no reason to think that is true. Consider the example of Calvinism. I was a Calvinist for two years (1999-2001), but I have been an Arminian ever since. (However, my post-2001 Arminianism is post-critical whereas my Arminianism of 1998 and earlier was pre-critical.) I certainly think I’m open-minded on this topic and I know many Calvinists who would agree with me. However, I can’t say what exactly would persuade me to change my mind. Exegesis of Romans 9? A powerful argument in favor of soft determinism? An argument for the incompatibility of libertarian free will with divine foreknowledge? I’m not sure.

In fact, if I were to change my mind again on this topic, what likely would happen is that various factors including some or all of the above could serve to erode my commitment to Arminianism leading to the moment when I suddenly come to realize, “Hey, I’m a Calvinist again!” You see, that’s typically how major belief conversions occur: slowly, over time, by way of multiple small steps culminating finally in one big change. But the ability to say precisely the moment when that would occur on a particular topic is typically something we don’t know. So to make the ability to identify that moment as an essential hallmark of openmindedness is simply misguided.

Is a conversation only worthwhile if your interlocutor has an open mind?

Now, let’s grant for the sake of argument that a particular individual is not, in fact, openminded. Surely we should move on then, right?

Maybe, but then again, maybe not: and this brings me to my second point of disagreement. Andrews assumes that this conversation is only worthwhile if your interlocutor is, in principle, open to changing her mind as a result of this conversation. But I disagree on that point as well.

It may be that your interlocutor isn’t openminded now. It hardly follows that they won’t be openminded tomorrow. But if you cut off the interactions now, you’ll never get to tomorrow. And how can you know that even now you aren’t slowly eroding her convictions and opening up her mind? The fact is that changes in belief can be occurring well before we recognize they are occurring. So the surface closedmindedness could be concealing a slow evolution in thinking that isn’t yet evident. And if you burn a bridge now, you may undermine that process.

Is a conversation only worthwhile if your interlocutor eventually changes her mind?

Finally, Andrews appears to assume that apologetic/evangelistic conversations are only worthwhile if they move your interlocutor toward changing her mind. But these kinds of exchanges can have all sorts of additional goods.

For example, maybe you need to change your mind. After all, nobody is right all the time. So whatever the mindset of your interlocutor, this conversation could be a powerful catalyst for your own intellectual development.

Here’s another possibility: your interlocutor may not change your mind, but maybe your exchanges with her lead you to become more effective at sharing your views and fielding criticisms. This too is a boon that could make a conversation well worthwhile.

And here’s one more possibility. This one is radical, but please keep, ahem, an open mind. What if you had conversations with people not simply to change their mind but because you wanted to cultivate a friendship with them and the amiable and spirited sharing of disagreement is part of friendship? In short, could friendship be a sufficient reason to have a conversation? Surely the question answers itself.

Conclusion

For all these reasons, I disagree with Andrews’ tweet. And in closing, let me note just one more point. While I recognize that Jesus uses the vivid metaphor of casting pearls before swine (Mt. 7:6) it doesn’t follow that we too should use that same metaphor in our contexts.

Put it this way. Consider how you’d feel if your interlocutor characterized your recent exchange with her in these terms: she cast her pearls of wisdom before your cloven porcine hooves. I suspect that you probably wouldn’t appreciate the metaphor. So if we’re going to quote from Matthew 7 to inspire and guide our apologetic and evangelistic conversations, let’s stick with verse 12:

“So in everything, do to others what you would have them do to you…”

The post When is an apologetic dialogue no longer worth pursuing? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

July 10, 2018

Atheism, Christianity, and Naive Empiricism

The term naive empiricism refers to the view that knowledge only comes through empirical means (e.g. science). It’s called naive because this strain of empiricism lacks nuance and fails to recognize the amount of information, belief, and knowledge which is not acquired through empirical means. The most famous naive empiricists of the twentieth century were the logical positivists, but logical positivism fell apart seventy years ago largely due to the internal contradictions with the view.

However, you’d never know it by talking to many lay people who identify as both atheists and skeptics. Within that crowd, the dated claim that all justified belief or knowledge must conform to scientific or empirical means is surprisingly common. For example, the armchair naive empiricist will say things like this:

“If I can’t see it, taste it, touch it, smell it, or hear it, it doesn’t exist.”

Or this:

“I’ll only believe in God if there is scientific evidence. For example, God could have written his name in DNA.”

Naive empiricism turns up in some strange places. Consider, for example, some recent comments from Rodrigo Duterte, the vulgar and bullying president of the Philippines. Duterte touts his own atheism and recently declared belief in God stupid. He went on to issue a surprising challenge: if anybody can provide a photograph of God, Duterte would resign the presidency. (Source)

Um, yeah…

But it isn’t just atheists and self-described skeptics who exhibit the characteristics of naive empiricism. Sometimes Christians do as well. I don’t know how else to describe this jaw-dropping, embarrassing case of popular preacher Louie Giglio citing the cruciform shape of the protein laminin as evidence for God:

The post Atheism, Christianity, and Naive Empiricism appeared first on Randal Rauser.

July 8, 2018

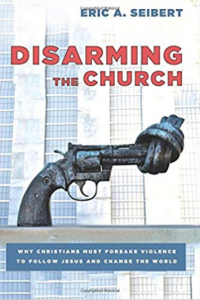

Reckoning with the Peaceable Kingdom: A Review of Disarming the Church

Eric A. Seibert. Disarming the Church: Why Christians Must Forsake Violence to Follow Jesus and Change the World. (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2018.)

Eric A. Seibert. Disarming the Church: Why Christians Must Forsake Violence to Follow Jesus and Change the World. (Eugene, OR: Cascade, 2018.)

Carl Norden was a devout Christian. So when he developed the Norden bombsight, it was with the intent of increasing the accuracy of aerial bombing to the end of decreasing the resulting collateral damage wrought by war. In short, the bombsight was meant to embody Norden’s Christian values lived out on the field of battle.

Unfortunately, while the bombsight promised deadly accuracy under ideal conditions, the theater of war rarely offers ideal conditions. As a result, the bombsight never lived up to its promise … though it was accurate enough on the day it was used to detonate an atomic bomb over Hiroshima.

The sad story of Carl Norden provides a salutary warning for all Christians who seek to live out their cruciform discipleship in service of war and violence. If I had more time, I could give you other examples such as the story of Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, a follower of Jesus whose hatred of executions led him to propose an ill-fated means of making them more humane.

But what, exactly, is the lesson? Do these examples simply offer a caution to Christians inclined to pragmatically adapt their convictions to realpolitik? Or is the real lesson that Christ calls us to lay down our weapons and set aside our violent inclinations even as we take up our cross?

An Overview

In his new book Disarming the Church, biblical scholar Eric Seibert defends the second view: to follow the Prince of Peace, he insists, requires a radical and categorical rejection of violence.

Disarming the Church is divided into four parts. Seibert begins in Part 1 (chapters 1-4) by summarizing the church’s problematic relationship to violence. Next, Part 2 (chapters 5-9) is devoted to presenting a case for non-violence based on the witness of the New Testament, and the life and teachings of Jesus in particular.

While Part 2 is the heart of the book, Seibert also recognizes the critical importance of narrating new ways to live peaceably. And so, he dedicates the final two parts of the book to exploring new ways of thinking with a range of practical alternatives to violence (Part 3; chapters 10-12) and a new vision for living non-violently every day (Part 4; chapters 13-17).

Defining Violence

If you’re going to argue that violence is incompatible with Christian discipleship, you should be clear as to what, exactly, violence is. Seibert recognizes this point and so he offers the following definition:

“Violence is physical, emotional, or psychological harm done to a person by an individual(s), institution, or structure that results in serious injury, oppression, or death.” (10)

Unfortunately, this definition is inadequate on two counts. To begin with, it is too restrictive insofar as it limits violence to injurious actions visited upon persons, a stipulation which would exclude human beings who are not (or not yet) persons (e.g. fetuses).

Admittedly, that problem can be fixed easily by replacing “person” with “human being”. More problematically, the definition intentionally excludes injurious actions against non-human animals or natural systems and structures. To be sure, there is a logic at work: Seibert’s definition of violence in terms of harm inflicted upon human persons reflects his focus in the book. But while Seibert has every right to limit the scope of his interest, the proper way to do this is by stipulating that you will limit your discussion to intrahuman violence, not by defining violence as intrahuman violence.

This brings me to the second problem: Seibert’s definition is also too rigorous. The point is illustrated with his unqualified condemnation of spanking:

“Regardless of how ‘lovingly’ it is done, or how controlled the parent may be while doing it, spanking is a form of violence.” (238)

While I agree with Seibert that spanking is violent, in most instances it is not sufficiently intense to inflict the serious injury, oppression, or death required by Seibert’s definition of violence. As a result, by Seibert’s own definition, most instances of spanking are not, in fact, violent. This shows us that Seibert’s definition of violence is too restrictive since it fails to recognize relatively mild examples of violent behavior.

After all that, you might be wondering how I would define violence. For the purposes of this review, I’m content to borrow Justice Potter Stewart’s famous statement on obscenity: we know it when we see it. But whatever our definition, we should recognize that violence comes in degrees of intensity ranging from mild (e.g. spanking) to severe (e.g. killing) and it can be inflicted not only on human persons (or beings) but also on other living creatures and living systems.

Violence is Bad

Part 1 is dedicated to identifying the church’s relationship with violence and the problematic nature of violence. Seibert avoids recounting a long history of crusades, pogroms, witch burnings, battles, and the like, opting to focus instead on the current state of the church. For example, he notes how the church in the United States is statistically more likely to support war and torture than the general population (18, 19). He also recounts examples of the church’s heightened rhetoric against various out-groups such as Muslims, atheists, and gay people.

Ultimately, the church’s acceptance of violence is rooted in what Jim Forest refers to as “the Gospel according to John Wayne” (34) according to which one deals with violence by way of more violence. In short, the church has bought into the myth of redemptive violence.

And it is a myth, or so Seibert argues in chapter 4, “The Truth about Violence: It’s All Bad.” In this chapter, Seibert amasses evidence that violence begets more violence, it escalates dangerous situations, it adversely affects innocent parties, and it has wholly negative psychological and emotional impacts on those who participate in it such as the “moral injury” of soldiers (54). The essence of the chapter is found in the sobering conclusion of one soldier:

“The biggest lie I have ever been told is that violence is evil, except in war …. My government told me that … I came back from war and told them the truth–‘Violence is not evil, except in war .. violence is evil–period.'” (Cited in 59)

The Prince of Peace

In part 2, Seibert makes a case for peace based on the New Testament (though he also briefly references OT sources for peace (61-3)). The heart of his case is the life and teaching of the Prince of Peace as surveyed in chapter 5. In the Sermon on the Mount, Christ taught his followers to be peacemakers (Mt. 5:9), to love our enemies (5:38-48), and to follow the Golden Rule (7:12).

While some people seem to view the pacifistic response as milquetoast discipleship, Seibert helpfully explains how actions like turning the other cheek, in fact, constitute a bold assertion of personal dignity and resistance to unjust oppression (66-67). In other words, the rejection of violence does not mean one is left to acquiesce in the face of oppression. Rather, it challenges us to pursue a courageous confrontation of evil and a prophetic anticipation of a better world.

Jesus modeled the peaceable kingdom in his own ministry. Throughout his life, he rejected violence and preached forgiveness (see, for example, Luke 9:51-56; 22:47-53; John 7:53-8:11), culminating, of course, in his atoning death on the cross. And we are called to take up our crosses in emulation of him (Luke 9:23).

Anybody who has spent any time debating these topics knows that critics of pacifism have a list of go-to texts in which Jesus seems to adopt a more positive attitude toward violence. Seibert offers a rebuttal to those various texts in chapter 6. For example, Jesus is recorded in Luke as saying “the one who has no sword must sell his cloak and buy one.” (22:36) Surely this text shows that Jesus did not accept pacifism?

No, Seibert insists, it doesn’t. Instead, he argues that the passage is best interpreted figuratively:

“By telling his disciples they should now take a purse and a bag, and should buy a sword if they do not have one, he is informing them, albeit figuratively, that grave dangers lie ahead. He is not giving them a laundry list of items to acquire…” (89, emphasis added)

At first blush, this might seem to be a strained response: if Jesus truly was a pacifist why would he use the image of wielding a sword to warn of hard times ahead? That said, Seibert points out that immediately after this curious direction, Jesus rebukes Peter for using his sword (Luke 22:50), a point that would seem to support the figurative interpretation of the text.

Seibert also addresses Jesus’ rhetorical violence against the scribes and Pharisees. While he concedes that Jesus’ language can be harsh, Siebert stresses that we need to understand Jesus in his historical context:

“We should not expect Jesus to sound like a contemporary peacemaker or nonviolent practitioner. Nor should we evaluate Jesus’ rhetoric by modern ethical standards and use those to accuse Jesus of being verbally violent.” (91)

While Seibert is right to note that in general, we should interpret people as creatures of their times, this is not how Christians historically view Jesus. Rather, they view him as the perfect God-man who exemplifies proper behavior for all time. And thus, if Jesus visits upon his opponents rhetorical barrages which are inflammatory if not violent, one cannot help but wonder whether this provides a principled basis for Christians to do so as well.

Narrating Peace

The biggest challenge to peace is probably the fact that people don’t believe true change can take place without violence. Siebert takes direct aim at that lingering belief in part 3. For example, he cites a major study of social change in the twentieth century which provides a striking statistic: “between 1900 and 2006, nonviolent resistance campaigns were nearly twice as likely to achieve full or partial success as their violent counterparts.” (185, emphasis Siebert’s) Seibert even notes how non-violence could provide a proper response to the Nazis (187 n.).

Statistics are suggestive, but to really change people’s thinking one needs story. As Seibert puts it, “stories are powerful. Stories engage our affect, and affect is critical for storing things in our brain and moving us to action.” (9) As a result, he weaves several stories into his narrative of people who rejected violence and embraced the way of peace. Many of those stories inspire the hope that peaceable living is a realistic possibility. Rather than summarize some of those moving accounts to you, I’ll direct you to CBC radio’s challenging story, “How one woman came to forgive the man who murdered her father.” If you are moved by that story, then it’s a safe bet that you’ll love Seibert’s book.

The last half of the book is also packed with practical tips for pursuing a peaceful mindset. In chapter 15 Seibert offers a treasure trove of reflections on non-violent parenting. He observes, for example, that the closer war toys are to reality, the more problematic they become. Thus, for example, the pacifist parent might permit play with the cartoonish Masters of the Universe but not the truer-to-life G.I. Joe series (244).

While I found many of these suggestions helpful, at times Seibert’s suggestions appear a bit pedantic and susceptible to the charge of virtue signaling. (Think, by analogy, of the vegetarian who never misses the chance to talk about the suffering of farm animals when you’re simply trying to enjoy your hotdog at the baseball game.) For example, he suggests a parent might respond to violence in video games by offering some pacifistic commentary:

“‘Wouldn’t it be really cool if there was a way to make friends with the ogre rather than destroying him?’ Or, ‘Wouldn’t it be neat if you could win the game by talking out your differences rather than shooting at each other?'” (242)

Um, yeah, maybe. But the typical kid is going to reply, “Dad, can’t I just play the game?” and at some point, I’m inclined to agree with him.

Conclusion

Disarming the Church provides an eloquent and impassioned defense of pacifism. What is more, it is thoroughly grounded in reality as is evidenced in the multiplicity of eminently practical proposals for pursuing a peaceable existence.

Having said that, I find myself unable to offer an unqualified endorsement of the book’s central thesis. My problem can be illustrated by the definition of violence that frames the discussion. You see, by this definition, chemotherapy is violent since chemotherapy often produces significant physical, emotional, and/or psychological harm in the individual (including, but not limited to a compromised immune system, fatigue, hair loss, and infertility). If I accepted Seibert’s definition of violence, I’d be obliged to say that since all violence is bad, it follows that chemotherapy is bad.

It’s important to understand that this problem cannot be dealt with by a simple fix like switching human person to human being. Rather, in my estimation, it goes to the core of the pacifistic thesis, because it seems to suggest that there are cases where violence is justified, such as in the case of the chemotherapeutic treatment of cancer. And if violence is justified in that case, one must consider whether it might be justified in other instances as well. Insofar as this remains an open question, it constitutes a significant objection to Seibert’s thesis.

This leads me to a more specific concern. Seibert’s pacifism constitutes a Christ-against-culture model which secures the church’s faithful, prophetic witness at the apparent cost of societal engagement. But this is a significant cost to pay. For example, while Seibert observes that the threat of the police can be a deterrent to violence (172), he does not explicitly grant the possibility that Christians might be part of this deterrent force given that the police officer must be open to the use of violence if required. Does this mean that Christian discipleship requires withdrawal from participation in all law enforcement? By the logic of Seibert’s argument, it would seem so. But some Christians will find this societal withdrawal to constitute an unacceptable consequence of pacifism.

I raise these issues not as refutations of Seibert’s thesis but rather as spirited reactions to it. The point to keep in mind is that they are reactions which are stimulated by a book which offers an undeniably powerful defense of its central thesis. I may not agree completely with the core thesis of Disarming the Church, but I am most definitely challenged by it, as will be all Christians who commit to reading this eloquent treatise on the peaceable kingdom.

You can order a copy of Disarming the Church here.

Thanks to Cascade for a review copy of the book.

The post Reckoning with the Peaceable Kingdom: A Review of Disarming the Church appeared first on Randal Rauser.

July 5, 2018

The problem with a god who suffers

The doctrine of divine impassibility was widely assumed by Christian theologians throughout the history of the church. But that consensus was fractured in the twentieth century with the decline of a widely held theological model belatedly known as “classical theism”. With the fracturing of a consensus on the classical theist model, several divine attributes were called into question, among them omniscience, atemporal eternity, and simplicity.

Arguably, the classical attribute subject to the most criticism has been divine impassibility, the claim that God does not suffer. The objections to impassibility have been many. To my mind, the most compelling objections focus on arguments from incarnation and have the following basic structure:

(1) Jesus Christ suffered.

(2) Jesus Christ is a divine person.

(3) Therefore, a divine person suffered.

(4) If a divine person suffered then divine impassibility is false.

(5) Therefore, divine impassibility is false.

But many other objections have been rather poor and misguided. Among the worst is based on the mistaken assumption that impassibility somehow entails apathy. In other words, if God doesn’t suffer when we suffer then God doesn’t care that we suffer. In still other words, if God doesn’t suffer with us then God doesn’t love us.

While that bit of reasoning has struck many people as compelling, the fact is that it is deeply flawed. After all, God the Father sent his Son Jesus to live the perfect life and die an atoning death to bring about the healing of creation. If that isn’t indicative of care and love then what is it?

But how can God love us if he doesn’t share in our suffering? This too is deeply misguided. And by way of rebuttal, I offer a quote from the doctor on The Horn.

Er, wazzat?

Allow me to explain. The Horn is a documentary series on Netflix which follows a team of experts headquartered in Zermatt — climbers, paramedics, doctors, and helicopter pilots — as they rescue stranded and injured people hiking in the Alps. At one point, the main doctor on the team describes the importance of separating emotion from one’s work with patients. He says:

“One must work with a patient completely without emotion. It’s the best for the patient and the best way for positive results.”

Here’s his point. If his goal is to benefit the patient, then it does precisely no good for the doctor to break down and weep as he witnesses the patient’s egregious injuries. Rather, as a doctor who longs to bring healing to the patient, it is critical for the doctor to set aside his own emotion and labor simply to apply his skills of healing.

Whether you agree with it or not, the same logic lies behind the doctrine of divine impassibility. God has identified with us and our suffering in Christ. But in his divine nature, God remains like that doctor: he works without the sway of emotions and in that way he brings about the best results for the patient.

The post The problem with a god who suffers appeared first on Randal Rauser.

July 4, 2018

Childhood may be more terrifying than you remember

Those of us who enjoyed a childhood bereft of any major trauma often think back to those days with a wistful nostalgia. That was the time before you needed to worry about adult things like job security, paying the credit card bills, and financing a looming retirement.

We often forget that childhood has stresses of its own like schoolyard bullies and monsters under the bed. In fact, if you think about it, some children live in a shockingly macabre world of their own making. Looking back, this was my experience.

To note one example: the entrance of our church featured two planters of approximately six feet in length, one on each side of the entry staircase. For some reason, I believed for years that each planter concealed a corpse. Wiggle your finger an inch into that dark loam and you would feel the sickening texture of decaying flesh.

To this day, I haven’t a clue as to where that idea came from. Was that dark image borne of a mischievous whisper from another child? Or did it emerge ex nihilo from my own over-active imagination mulling the coffin-like shape of those planters?

I haven’t a clue. But I do know that for years I thought our church inexplicably featured two corpses at the entrance. From that perspective, the worries of adulthood aren’t that bad, after all.

The post Childhood may be more terrifying than you remember appeared first on Randal Rauser.