Randal Rauser's Blog, page 95

August 7, 2018

Why doesn’t God give everyone a miracle?

Some years ago, a friend of mine told me how, after losing his wife to cancer, he encouraged his embittered young adult children to return to church. On their first visit to a small group, several people shared their recent answers to prayer — miracles, they said — while the two young visitors sat quietly. When they returned home that night, my friend’s kids asked one question: “Dad, if God answered all those prayers, why didn’t he answer ours?” In short, if God gives people miracles, why doesn’t he give everyone a miracle?

The miracle

I want to back into that question with a miracle of my own.

When I was about ten years old, I was riding my bike home from school when I crossed the street just up the hill from our house … except this time I didn’t do my usual shoulder check for oncoming traffic. A second later I suddenly heard a car horn blast followed by the sickening squeal of tires. Then, just as I turned to my left I saw the grill of a large Buick as if it were hovering but a few terrifying feet away from me. You know how people talk about time slowing down when their life is in danger? That describes my experience. Though it was a mere split second, even now I can still visualize the grill of that Buick, frozen in time, looming in space mere feet away from me.

The next moment I was sent sailing through the air and rolling on the asphalt as the car came to a lurching halt on the graveled shoulder of the road. Here’s where the miracle bit takes center stage. Incredibly, I never felt the impact of the car. At the moment when I should have been making contact with a chrome grill, all I felt was a cushion of air. Even more incredibly, though I had been sent flying off my bike and skidding on the asphalt with no helmet or pads, I got up with no injuries at all, save a single scrape on my elbow.

Shortly thereafter, as I was wheeling my bike up the driveway, our Christian babysitter, Mrs. White, burst out the front door. She said that she had been sitting on the couch watching TV when God told her that I was in trouble and she needed to pray for my safety. So pray she did until she sensed God telling her that the danger had passed.

The Problem

These days I can’t share that story without acknowledging a range of additional issues that I never thought to ask when I was ten. Perhaps the most difficult one is this: for every child that God miraculously saves from a fatal injury, there are countless others he does not save. Why is that? The problem was memorably stated by the 19th-century skeptic, Robert Ingersoll:

“Only the other day a gentleman was telling me of a case of special Providence. He knew it. He had been the subject of it. A few years ago he was about to go on a ship, when he was detained. He did not go, and the ship was lost with all on board. ‘Yes!’ I said, ‘do you think the people who were drowned believed in special Providence?’ Think of the infinite egotism of such a doctrine.”

Frankly, it would be a lot simpler if God just never intervened on principle. But once he starts making exceptions, once he starts getting involved, once he spares the life of one child but not another, it’s difficult to escape the uncomfortable feeling that he’s playing favorites.

The problem is heightened for me as I consider another car accident near my childhood home when a young girl was run over and killed by a dump truck. If God reached down into spacetime to place an invisible divine finger between me and the front grill of a Buick, why didn’t he do something similar for this young girl? If God saves some children, then why doesn’t he save all of them? Again, it’d be one thing if it was God’s general policy not to get involved in the details: in that case, that’s just the way it is. But once he abandons a non-intervention policy in order to ensure that the grill of a Buick never comes into contact with one particular kid, the question looms: why doesn’t God intervene in other cases?

Looking for Answers

These are haunting questions, and over the last twenty years, I’ve invested a lot of time thinking about them. While there is much I could say on this very difficult topic, I’ll limit myself to four points.

First, if you believe that God is all-powerful, all-knowing, and all-good, it follows that he must have some purpose in acting as he does. The fact is that as all-powerful, God could have stopped the garbage truck from hitting that girl. As all-knowing, he would have known the truck was about to hit that girl. And as all-good, he would never want any person to suffer without a morally sufficient reason. From this, it follows that when a terrible event like this occurs, it isn’t because it escaped God’s power or knowledge. And it certainly isn’t because God is less than perfectly good. Rather, it must be because God has a morally sufficient reason why he allowed that event to occur.

Second, while God has his reasons, when people are in the midst of suffering they typically don’t want to hear what those reasons might be. And they also don’t want to hear well-intentioned attempts to lessen the suffering with so-called “comfort words” that end up offering anything but comfort. A few years ago a friend of mine lost his daughter in a car accident. He noted that in the wake of the accident countless well-meaning Christians said to him “Well at least…” and then they would say things like “… she’s in heaven” or “… you’ll see her again.” No doubt, those folks meant well, but the words “Well at least” still ended up being salt in his wounds. The moment he heard them, he would automatically tune out Job’s comforters. With that warning in mind, what does one say to those in deep suffering? The simple answer is, when in doubt just say nothing. Instead, just be with those who suffer.

Third, while we will probably never know the reasons God allows terrible events, we can know that he doesn’t perform miracles because people somehow deserve them. If God opted to spare my life from a Buick while not sparing the life of that young girl from a garbage truck, it is not because of any difference in us. It isn’t because I had somehow earned the right to be saved as if I’d logged a few more brownie points for good behavior. Rather it must be due to God’s sovereign purposes alone, whatever those may be.

Now for my final point: what is the proper response of those who believe they experience a miracle? While I’ll be the first to admit that many questions remain, my conviction also remains that God did indeed intervene at a particular moment to spare my life. In light of that fact, the best I can do is to seek always to live in a way that honors the merciful gift of my life.

I know I said that was my final point, but there’s one more thing I want to say: even though I was spared, the fact remains that someday we all shall die. Even the greatest miracles experienced by God’s human creatures are at best a temporary reprieve from their inevitable demise. In that sense, a miracle now is but a promissory note on a future time when all shall be well.

This article is based on a section of my book What’s So Confusing About Grace? You can order the book here.

The post Why doesn’t God give everyone a miracle? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

August 5, 2018

Ten Years After the Atheist Bus Campaign: Some Reflections

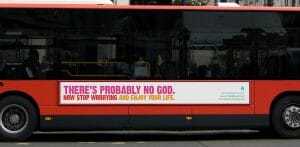

It may be hard to believe, but it has been ten years since the Atheist Bus Campaign posted ill-conceived signs on European buses with the trite caption: “There’s probably no god. Now stop worrying and enjoy your life.”

It may be hard to believe, but it has been ten years since the Atheist Bus Campaign posted ill-conceived signs on European buses with the trite caption: “There’s probably no god. Now stop worrying and enjoy your life.”

Note to atheists: when you finally grab the microphone, try to have something more profound to say than “Enjoy your life.”

For example, you could say something like “Let’s make the world better. It’s up to us!” Or perhaps “Love your neighbor, because there is no god to do it.”

But instead, you settled on the trite, narcissistic “Enjoy your life”. Talk about a lost opportunity. How very disappointing.

No wonder that ten years on, theists are still having a chuckle…

The post Ten Years After the Atheist Bus Campaign: Some Reflections appeared first on Randal Rauser.

August 4, 2018

Dementia: A Philosopher’s Lament

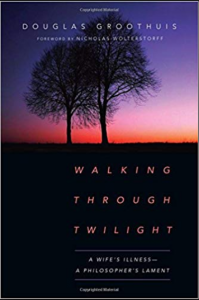

Douglas Groothuis. Walking Through Twilight: A Wife’s Illness–A Philosopher’s Lament (Downer’s Grove, IL: IVP Books).

Douglas Groothuis. Walking Through Twilight: A Wife’s Illness–A Philosopher’s Lament (Downer’s Grove, IL: IVP Books).

On December 19, 2017, we received the official diagnosis: Alzheimer’s disease. While it was terrible news — a literal death sentence — we were not surprised: Dad had been on the decline for months, and truth be known, the doctor was merely confirming what we already knew.

Dementia in its various permutations impacts countless families and as it does, it raises a nest of extremely difficult questions about the nature of suffering and the goodness of God.

In his new book Walking Through Twilight philosopher Douglas Groothuis offers a unique perspective on this difficult topic. Written as equal parts memoir, lament, and philosophical reflection, the book chronicles Groothuis’ own journey with his wife Becky as she slowly walks into the enveloping fog of dementia.

Becky was diagnosed in 2013 with Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA), a form of dementia that begins its cruel attack in the frontal lobe as it progressively robs the patient of the ability to speak. The impact of the condition on an author and noted wordsmith like Becky Groothuis is especially tragic:

“Becky could write a perfectly structured, flawlessly decorated, and marvelously coherent sentence that went on for seventy-five words–all without pomp, without verbosity, with grace, with truth, and which never overtaxed the reader’s patience or intelligence. Now she never touches a keyboard or picks up a pen; she must fight a bloody war to secure the simplest word. She is muted. Words no longer serve her. Words fail her. She has been yanked away from the banquet of language and put on a starvation diet.” (134)

Walking Through Twilight is a collection of vignettes and poignant reflections on life, love, suffering, providence, and hope. The fact that Douglas Groothuis is an analytic philosopher is readily apparent as he carefully analyzes the meaning of a concept like lamentation (59-61). For example, while lament is important, Groothuis sagely observes that “biblical lament is not grumbling, which is selfish, impatient, and pointless.” (61) (As a consummate grumbler, I took that bit of advice to heart.)

Groothuis’ analytic skills are also on display in chapter four as he characterizes the state of Becky’s illness as eerie, a state which he explains as simultaneously unexpected, unusual, opaque, and frightening (28).

Like a tree laden with fruit for harvest, Walking Through Twighlight is rich with provocative insights and reflections. For example, in the spirit of the penetrating wisdom of Ecclesiastes Groothuis bluntly asks:

“Is this all futility with a thin dusting of meaning, or is it meaning with a thin dusting of futility?” (80, emphasis in original)

The Christian professes the latter, but those who journey through the dark night of the soul cannot help but ask the former. With admirable honesty and bluntness, Groothuis leads the way.

The particular demands of communication with Becky as she loses her vocabulary reminds Groothuis of the need to focus on our social interactions with others: “How can we be present with another creature made in God’s image when we are absent, somewhere else on our smartphone?” (99) Indeed, that lesson on true presence has a wide application: let us hope we learn it long before our loved ones are diagnosed with dementia.

Another common problem arises when would-be comforters end up saying something hurtful. Groothuis offers some eminently practical wisdom: “Silence may not heal, but it does reduce the pains inflicted by a loose tongue.” (168) In other words, when in doubt, shut up and just be there.

As a professor, preacher, and public speaker, Groothuis must decide how much of his personal struggles he should reveal to an audience. On the one hand, he rightly observes that the willingness to share your personal grief and struggle brings power and authority (84). It’s one thing to talk about suffering in the abstract, but quite another when it is your suffering of which you speak.

On the other hand, Groothuis also cautions that we need to be careful that we do not fall into the trap of “emotional promiscuity” or “oversharing” (85). That’s a very important point: there is a fine line indeed between strategic vulnerability and lapsing into codependency with one’s audience.

Incidentally, the same point applies to written works: here too it is important to find the balance of judicious emotional vulnerability and Groothuis gets it just right. The book begins with a moment of honest vulnerability chronicled in the aptly titled chapter 1: “Rage in a Psych Ward.”

Groothuis is no emotional profligate, but he later gives us a genuine glimpse into the struggles of the caregiving spouse:

“divorce is often the escape for a spouse. Marriages afflicted by chronic illness often melt in the fires of despair, anger, and frustration. I have endured the feeling of ‘I cannot take it anymore’ countless times–sometimes several times a day.” (140)

However, it isn’t all the valley of despair: searing passages of anger, uncertainty, and exhaustion are nicely complemented with the tender intimacy of a husband and wife sharing an all-too-rare intimate moment of connection (159).

Through the difficult years, Groothuis recounts the support of many family and friends, but perhaps the most important of all is Sunny Groothuis, a vibrant Golden Labradoodle. Time and again, Sunny is there to offer comfort and hope in life’s dark moments, though Groothuis does note with some puzzlement the dour perspective the biblical authors take toward the canine species (115).

Walking Through Darkness was published in November 2017 and Becky Groothuis passed away a few months later on July 6, 2018. But in this moving and reflective memoir, her impact will live on.

Thanks to IVP Books for a review copy of Walking in Twilight. You can order the book at Amazon.com.

Today, Becky is cremated.

Ashes to ashes.

Dust to dust.

Dust to resurrection.

— Douglas Groothuis (@DougGroothuis) July 13, 2018

The post Dementia: A Philosopher’s Lament appeared first on Randal Rauser.

August 2, 2018

Is atheism a more hopeful view of the future than Christianity?

Honestly, it's one of the best facts about life that major religions like Christianity and Islam are false. There is no hell, no billions of people suffering eternal conscious torture. Simple non-existence after death is literally infinitely better.

— Counter Apologist (@CounterApologis) August 2, 2018

I have often heard atheists express sentiments like this, so when this tweet popped up today, I decided to reply. My reply was simply this:

“Christianity per se does not include the belief that ‘billions of people suffer eternal conscious torture.’ It does include the belief that, to borrow a line from MLK, while the arc of the moral universe is long, it bends toward justice. Surely you would like that to be true, no?”

Let’s unpack this. The final section of the Apostles’ Creed reads as folllows:

I believe in the Holy Spirit,

the holy catholic Church,

the communion of saints,

the forgiveness of sins,

the resurrection of the body,

and the life everlasting. Amen.

Note how there is no mention here of the nature of suffering for the lost. Consequently, the Apostles’ Creed is fully consistent with various theories of posthumous punishment (e.g. divinely inflicted torment; self-inflicted torment; destruction/annihilation). Nor, for that matter, is there any discussion of the ratio of saved-to-lost. Thus, the Apostles’ Creed is also consistent with belief in universal restoration (e.g. as in Origen and Gregory of Nyssa).

What the Creed does outline is the fact that the creation will ultimately be set to rights, that God’s perfect justice will be done (Matthew 6:10), that all will be well (Isaiah 3:10), that every tear will be wiped away (Revelation 21:4), that God will be all in all (1 Corinthians 15:28).

Thus, as I said, Christianity minimally commits us to the view that while the arc of the moral universe is long, it bends toward justice.

With the exception of those persons who are themselves interminably wicked and opposed to justice, the rest of us surely ought to hope that this vision of reality is actualized, that God’s perfect justice will be done, that all will be well, that every tear will be wiped away, and that God — the absolute and transcendent source of all goodness — will be all in all.

The post Is atheism a more hopeful view of the future than Christianity? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

July 29, 2018

Is divine command theory a danger in the hands of the mentally ill?

Last year, Christian radio host Justin Brierley published his apologetics book, Unbelievable. It’s a delightful book — clearly argued and engaging to read — so much so that it even earned an endorsement from yours truly! It also earned a book-length response from several atheists, predictably titled Still Unbelievable.

Ever the hospitable host, Justin has invited two of the authors of Still Unbelievable to appear on a forthcoming episode of his radio program “Unbelievable.” (To recap, Justin invited two authors on “Unbelievable” to discussion Still Unbelievable, a response to Unbelievable.)

Justin also invited me to be his wingman on the program. And in preparation for the show, I’ve been reading through Still Unbelievable.

As you can probably guess, there is much in Still Unbelievable with which I disagree. Perhaps most disappointingly, the overall tone of the contributors is contemptuous of Christian belief. Christianity is not a serious intellectual system worthy of careful consideration: rather, it is a retrogressive worldview that belongs to childhood. And it is only cognitive dissonance and intellectual regression that allows us to think otherwise.

Along the way, the book also raises countless objections, though rarely are they developed with any rigor. And in this article, I want to address one of those examples. One of the authors, Michael Brady, raises the charge that divine command theory ethics is especially prone to abuse by the irrational/delusional individual:

“Some Christians are willing to go all in, and give it all to God. Under Divine Command Theory (DCT) the fideist is committed to doing whatever his God tells him to do. We correctly live in fear that such a person might experience a mental health crisis.”

I decided to interact with this charge because it is one I’ve heard oft repeated. It is also an objection based on a crude rendering of DCT and is consequently utterly without merit.

So note the following. First, DCT is typically a theory of the origin and nature of moral obligation, not moral value. In other words, God does not command what is good and evil but only what our specific moral obligations are toward that which is good and evil. Consequently, the person who believes God is generating moral values by divine fiat simply misunderstands what the theory is.

Second, the DCT theorist is not committed to the view that God performs particular speech acts directed at various individuals to command them what to do: e.g. “Hey, Billy, this is God. I command you to sacrifice your sister!” And I don’t know any DCT theorist who believes moral knowledge comes about in this ad hoc manner.

Note as well that the DCT theorist could believe that God’s commands are discerned in various public and objective means, e.g. through deeply-seated and universally held moral intuitions or through rigorous deductive arguments, for example.

This leads me to a third observation. The force of Brady’s objection really is on the seemingly instantaneous and arbitrary nature of DCT, as he sees it. Thus, for example, Brady fears the individual that suddenly concludes that God wants him to do x. (For further discussion, see my conference paper “I want to give the baby to God: Three theses on God and devotional child killing.”)

But note that if you truly are mentally ill, you will find a rationalization for your actions whether you’re a DCT theorist or not. You may be a secular Kantian deontologist, a Millsian Utilitarian, a relativist, an antirealist, or an Aristotelian virtue theorist: it hardly matters. But if you decide it is right and perhaps obligatory to commit some heinous action, you will find a way to justify your actions. There’s no justification to single out DCT as especially “dangerous”

To sum up, those who think that DCT provides some unique ability to justify heinous actions understand neither DCT nor the self-justifying resources of those with mental illness.

The post Is divine command theory a danger in the hands of the mentally ill? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

July 28, 2018

Naturalism and Faith

For those who don’t follow me on Twitter, my morning salvo against naturalism:

Few things are as ironic as a naturalist chiding a Christian about having "faith".

— Tentative Apologist (@RandalRauser) July 28, 2018

I then added: “Footnote: by “naturalist” I mean a person who believes (i) all that exists is matter or supervenes on matter or (ii) all that exists is that which is described by the hypothetically complete natural sciences. I don’t mean somebody who eats granola or disrobes whilst in nature.”

The post Naturalism and Faith appeared first on Randal Rauser.

July 27, 2018

Would Jesus want you to stay married to a psychopath?

This morning, I tweeted the following survey:

Clinical psychopaths are manipulative anti-social narcissists who are incapable of experiencing love or empathy. The condition is untreatable. If you came to believe your friend was married to a non-violent psychopath, would you support your friend divorcing that individual?

— Tentative Apologist (@RandalRauser) July 27, 2018

As of this writing (9 hours after the survey was posted), fully 87% believe that the individual would be or may be justified in divorcing the psychopathic spouse. Conversely, a mere 13% of respondents believe that a person is obliged to remain married to a clinical psychopath.

While I don’t know how many respondents are Christian, given the extreme nature of this contrast, it would seem a safe assumption that even a survey limited to Christians would result in a minority insisting that person is required to stay married.

Interestingly, when Jesus talked about grounds for divorce, he only mentioned the case of one spouse committing porneia (Matthew 19:9). Porneia is translated variously as “fornication” (KJV), “sexual immorality” (NIV, ESV, HCSB), “unfaithful” (NLT), “immorality” (NASB, NET), “terrible sexual sin” (CEV).

What it clearly doesn’t include is a case where one spouse suffers from an untreatable personal disorder that results in them being a manipulative anti-social narcissist who is incapable of experiencing love or empathy.

The important thing to recognize is that those Christians who conclude that Jesus would permit divorce (and perhaps remarriage) in cases where one spouse is married to a clinical psychopath are not thereby “liberals” who are denigrating the authority of Scripture. (To be sure, they might be that: my point is simply that taking a lenient view on divorcing a psychopath is insufficient to support that conclusion.) Rather, they may simply recognize that experience plays an important role in clarifying and articulating doctrine and the ethical life.

From that perspective, the underlying issue is not whether or not Scripture is authoritative: all parties may agree that it is. Rather, the question is this: how ought Scripture to function within the community of faith? To wit, does it provide a comprehensive rulebook for every possible moral eventuality? Or, conversely, does it rather provide general principles that the community of faith must then work out in the complexities of life? Neither view is obviously the correct one, nor will it settle the matter to cite a passage like 2 Timothy 3:16-17 since that passage completely underdetermines this question.

And for this reason, a Christian may uphold the authority of Scripture as God-breathed words to teach, rebuke, correct, and train in righteousness whilst recognizing that unforeseen circumstances — like the psychopathic spouse — may force us to bring new questions to the text, and work prayerfully to clarify what we believe the right answers to be.

The post Would Jesus want you to stay married to a psychopath? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

July 25, 2018

The Ten (or more) Commandments of Christian Fundamentalism

In my memoir What’s So Confusing About Grace? I recount my experiences growing up fundagelical. The term “fundagelical” is (as you probably guessed), a portmanteau of “evangelical” and “fundamentalist,’ and in my opinion that descriptor ably captures the distinct characteristics of my religious and cultural upbringing.

So fundamentalism is a big part of being fundagelical. This morning I tweeted seven commandments of fundamentalism and I invited others to share their own proposed commandments. I received several intriguing responses (with more coming in) and have added a few of them to my original list.

Thou shalt vote Republican

Thou shalt oppose abortion

Thou shalt protect gun rights

Thou shalt support the military

Thou shalt oppose gay marriage

Thou shalt make America great again

Thou shalt oppose evolution

Thou shalt support Israel unapologetically

Thou shalt only support abstinence-only sex ed

Thou shalt deny climate change

Thou shalt have no Creed but the Bible (which is a creed)

Not surprisingly, some of these are particular to the American experience (notably 1, 3, and 6, and to a lesser extent, 4), while others are of comparatively recent vintage (i.e. 5 and 10).

In What’s So Confusing About Grace? I note another “commandment” which could well be included on this list: Thou shalt read the Bible literally where possible.

Which other “commandments” would you include on a fundamentalist list?

The post The Ten (or more) Commandments of Christian Fundamentalism appeared first on Randal Rauser.

July 24, 2018

Jesus could not sin. So was he really tempted?

Divine impeccability refers to the attribute of being unable to sin. Christians believe that God is impeccable in this sense. But they also believe that Jesus was tempted. Is there a problem here?

Last week, I tweeted the following two brief arguments:

Argument for Christ’s impeccability

1. A divine being cannot sin

2. Jesus is divine

3. Therefore, Jesus cannot sin

Argument for Christ’s peccability

i. If you can be tempted, then you can sin

ii. Jesus could be tempted

iii. Therefore, Jesus could sin

Both arguments are logically valid. And the conclusions are logically contradictory. Thus, it follows that the Christian must reject 1 and/or 2 or i and/or ii.

I propose that 1 and 2 are non-negotiable. Thus, the Christian should reject i and/or ii.

One problem to note is that when people read the word tempt they assume it refers to an object or act which is particularly attractive to the individual. For example, “That chocolate cake was tempting but I ate carrot sticks!”

However, there is no sense in the Gospel temptation narratives that Jesus was tempted in this manner. Instead, he repeatedly shuts down the devil’s proposals with quotations from scripture. Thus, insofar as one assumes temptation involves attraction, it is misleading if not flatly wrong to say that Jesus was tempted.

However, the Greek word translated “tempt” (peirazo) can also be translated as test, and of course to be tested involves no implication of attraction to that thing by which one is tested. From this perspective, the Christian has excellent grounds to conclude that while Jesus was not tempted in the sense of being attracted to some object or act, he was tempted in the sense of being tested. And being tested clearly does not require that one could have sinned.

The post Jesus could not sin. So was he really tempted? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

July 22, 2018

A famous atheist contrasts philosophy, science, and theology

At the beginning of his classic History of Western Philosophy, Bertrand Russell offers the following distinction between philosophy, theology, and science:

“Like theology, it [philosophy] consists of speculations on matters as to which definite knowledge has, so far, been unascertainable; but like science, it appeals to human reason rather than to authority, whether that of tradition or that of revelation.”

To summarize:

Science

Achieves definite knowledge

Appeals to human reason

Philosophy

Speculates on matters lacking definite knowledge

Appeals to human reason

Theology

Speculates on matters lacking definite knowledge

Appeals to revelation/authority

It’s a nice and tidy contrast. Too bad that it is also self-serving drivel.

The fact is that there is no tidy contrast between “philosophy” and “theology”. Consider, philosophy of religion is one of the main branches of philosophy. And philosophical theology is one of the main branches of theology. Yet, there is no clear demarcation between philosophy of religion and philosophical theology. To be sure, various practitioners may try to propose one or another point of contrast, but there will be as many practitioners who emphatically dispute that any such distinction exists. So, for example, is a defense of the Trinity by way of material constitution and relative identity an argument pertaining to philosophy of religion or philosophical theology? The answer is both.

Second, note that religion and theology also impinge on many other philosophical topics. Platonism, for example, is one of the most famous and enduring of all philosophical theories. Sometimes Platonism is simply expressed as the view that abstract universals exist apart from any concrete exemplifications. But in other expressions, such as the view held by Plato himself, Platonism is a significantly richer metaphysic which includes a teleological framework and the existence of a quasi-divine Form of the Good. In other words, Plato’s own expression of Platonism is quite religious. In other words, it is a theological theory as surely as it is a philosophical one.

Alfred North Whitehead famously observed that the history of philosophy is but a series of footnotes to Plato. Hyperbole? Definitely. Nonetheless, the influence of Plato’s philosophy/theology on western philosophy has never been exceeded. It also utterly fails to respect Russell’s tendentious and self-serving distinction.

There is much else to reject in Russell’s mapping of the disciplinary boundaries. For example, assuming one does not buy into some tendentious empiricism, both philosophical and theological arguments can produce knowledge. (For a full account, see my book Theology in Search of Foundations (Oxford University Press, 2009.) And scientific knowledge is often lauded for the very fact that it is always tentative and forever open to revision pending further data, a fact that makes Russell’s claim that science produces definite knowledge rather curious.

So what’s the lesson here? Simply this: don’t let ideologues set up the parameters of the conversation with self-serving definitions and categories.

The post A famous atheist contrasts philosophy, science, and theology appeared first on Randal Rauser.