Randal Rauser's Blog, page 97

July 3, 2018

If the Bible is a map for how to get to heaven, it isn’t a very good one

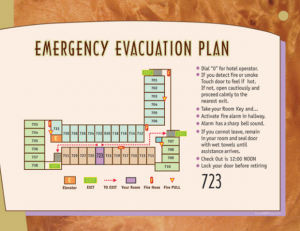

We’re all familiar with the fire evacuation maps on the inside of a hotel room door. In a brief, succinct, and luminously clear manner, the map provides directions for evacuating the building in case of fire.

We’re all familiar with the fire evacuation maps on the inside of a hotel room door. In a brief, succinct, and luminously clear manner, the map provides directions for evacuating the building in case of fire.

Growing up, I was taught to think of the Bible as like God’s hotel fire evacuation map for the human race. To be sure, I don’t ever recall that precise analogy being used. Nonetheless, it aptly describes the view of the Bible with which I was raised: a succinct (if not exactly brief) and luminously clear set of directions for evacuating earth and avoiding hellfire.

After spending the last fifteen years as a seminary professor, I can say without a doubt that the Bible is most certainly neither brief nor succinct. I can also say that this dizzyingly complex and diverse omnibus of ancient writings written over a span of a thousand years in three languages does not provide a luminously clear set of directions for evacuating earth and avoiding hellfire.

So where does this false picture of the Bible come from? And how was it maintained despite the evidence to the contrary? Looking back, it would seem that the evangelical subculture in which I was raised interpreted the Bible through a particular grid which included the Four Spiritual Laws and the so-called Romans Road to Salvation. Because the Four Spiritual Laws and the Romans Road were simple, we assumed that the Bible itself was simple, a straightforward evacuation map to get us to heaven. These brief statements captured the essential kernels of Scripture. The rest, if not quite chaff, was nonetheless of secondary import.

This picture of the Bible dominated my understanding for years, but as I recount in my book What’s So Confusing About Grace? over the years this picture began to erode. The fact is that we were, in essence, treating Bill Bright’s Four Spiritual Laws and that select list of verses dubbed the Romans Road as the keys to unlocking the Bible’s evacuation map.

But if that was really the case, then why didn’t God include the Four Spiritual Laws when he first inspired the Bible? Why did the church need to wait two thousand years for Bill Bright to summarize the entire book in a single tract? And if a particular set of verses in Romans provided the key to salvation, why didn’t the early Greek manuscripts of Romans underline or boldface those specific verses?

And what about all the material in the Bible which didn’t contribute to the four laws and Romans Road? To be blunt, from this perspective much of the Bible appeared to be unnecessary, perhaps even a distraction from the essential principles which relayed the salvific escape route.

Eventually, I came to the conclusion that the Bible is not an evacuation map. Neither, for that matter, is it an owner’s manual for the human life, or a love letter from God, or any number of other well-intentioned but woefully limited metaphors.

So what is the Bible? To begin with, it is a rich and complex collection of writings, one that ranks among the great literary collections of the world. This collection narrates the grand story of God’s action in history with his people through creation, fall, and redemption, culminating in the incarnation, atoning death, glorious resurrection, and anticipated second coming of God the Son.

But Christians believe this story is not simply a literary collection. We also believe it is divinely inspired (theopneustos). And in 2 Tim. 3:16-17 Paul explains that as a divinely inspired text, the Bible’s purpose is not simply to provide an escape route from planet earth. Rather, the Bible exists to transform the reader by teaching, rebuking, correcting, and training in righteousness.

And here’s the thing: transformation is not brief. Nor is it succinct or luminously clear. On the contrary, it is often messy and ambiguous. Far from being a straightforward map of escape from the world, the Bible is, as the great Swiss theologian Karl Barth once observed, an invitation to a strange new world. And it invites us into that world on a journey that will take a lifetime. So let’s set aside the simplistic, if well-intentioned summaries, open the book, and let the journey begin.

The post If the Bible is a map for how to get to heaven, it isn’t a very good one appeared first on Randal Rauser.

July 2, 2018

Does the Bible condemn same-sex relationships? A Response to Michael Brown (Part 3)

In this article, I continue my response to Michael Brown’s response to my review of his book Can You Be Gay and Christian?

In this article, I continue my response to Michael Brown’s response to my review of his book Can You Be Gay and Christian?

For starters, here is the link to the third part of my review of Brown’s book. In this section of my review, I explore the position that I call, for lack of a better term, the Weak Harmony Thesis (WHT). According to the WHT, the Bible neither explicitly condemns monogamous, committed same-sex relationships, nor does it explicitly commend them. Rather, the WHT claims that counterfactually had the biblical authors been aware of innate same-sex attraction and committed same-sex relationships, they would have approved of them.

That’s a quick summary of the challenge I raise in the article (though there is more to my response which I’ll address below). Here is Brown’s response to this argument on his show The Line of Fire:

https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/tentativeapologist/Brown+Part+3.mp3

* * *

Same-Sex Attraction in the Ancient World

In his response, Brown argues that the ancient world was aware of innate same-sex attraction and committed same-sex relationships. As a result, one cannot dismiss biblical — and specifically, Pauline — prohibitions by claiming that innate same-sex attraction and committed same-sex relationships are a modern phenomenon of which the biblical authors would have been unaware. This is, in fact, demonstrably false.

While Brown doesn’t offer a reference in this brief radio excerpt, I can provide one here. See this article by Robert Gagnon beginning on page 140. In the passage, Gagnon summarizes several ancient Greco-Roman theories that offer a biological basis for same-sex attraction. This survey provides excellent evidence that these concepts of innate same-sex attraction and same-sex relationships were widely known in the Greco-Roman world in which Paul lived.

It seems to me that Gagnon and Brown are correct on this point. However, that does not end the conversation because in my original part 3 article, I also raised a deeper objection to which I now turn.

Imperfect Biblical Wisdom?

While Brown provides a good reason to think that the biblical authors (most importantly, the Apostle Paul) would have some awareness of innate same-sex attraction and monogamous same-sex relationships, he doesn’t address my final point. What of those who might concede that Paul may well have rejected same-sex relationships as we understand them, but in that case, Paul would simply be wrong?

I present the outline of the argument in the section “Would God allow the biblical authors to offer less than perfect advice?” In that section, I point out that Christians widely reject the Bible’s teaching on corporal punishment. While several biblical authors endorse the wisdom of physically beating children, Christians today widely reject that teaching. And in cases where they purportedly accept it — as with Focus on the Family’s qualified endorsement of spanking — they are nonetheless still rejecting the much more severe beating endorsed by biblical authors. (For further discussion of these points, see my review of William Webb’s book Corporal Punishment in the Bible.)

This leads us to the following progressive challenge: just as the conservative rejects biblical teaching on corporal punishment based on evidence that physical beating is wrong and harmful, so the progressive rejects biblical teaching on same-sex attraction based on evidence that a categorical prohibition of same-sex relationships is wrong and harmful.

Note that if the conservative replies that the progressive is effectively abandoning biblical inerrancy, the progressive can reply that the conservative has already done the same, at least as regards corporal punishment. And if they are open to abandoning it in one case, then they should be open, at least in principle, to rejecting other aspects of biblical ethical and prudential teaching as well.

If one concedes that much, then the focus would shift to evaluating evidence for the claim that the biblical prohibition on same-sex attraction and same-sex relationships is indeed false and harmful.

As I said, Brown doesn’t address this argument in his rebuttal. This is unfortunate, because it seems to me that here lies the deeper and more daunting challenge to the traditional prohibition of same-sex relationships.

The post Does the Bible condemn same-sex relationships? A Response to Michael Brown (Part 3) appeared first on Randal Rauser.

July 1, 2018

Pastor to the Ragamuffins: A review of Pastrix

Nadia Bolz-Weber’s memoir Pastrix: The Cranky, Beautiful Faith of a Sinner & Saint (published 2013) has been getting a lot of buzz over the last few years. It was a New York Times bestseller. On Amazon.com, the book has almost one thousand reviews averaging five stars. These days Bolz-Weber has become one of the leaders of wild-goosey progressive Christianity. The progressives are reading Pastrix for inspiration and the conservatives are reading it for ammunition. Bottom line: everybody who is somebody has read or is reading Pastrix.

Nadia Bolz-Weber’s memoir Pastrix: The Cranky, Beautiful Faith of a Sinner & Saint (published 2013) has been getting a lot of buzz over the last few years. It was a New York Times bestseller. On Amazon.com, the book has almost one thousand reviews averaging five stars. These days Bolz-Weber has become one of the leaders of wild-goosey progressive Christianity. The progressives are reading Pastrix for inspiration and the conservatives are reading it for ammunition. Bottom line: everybody who is somebody has read or is reading Pastrix.

And since I like to think that I too am a somebody, I decided I better jump on this bandwagon.

The book was an easy read. We learn about Bolz-Weber’s struggle with the Protestant fundamentalism in which she was raised, her spiral into and journey out of substance abuse, the challenges of seminary and her own Lutheran denomination (the ELCA), and the highs and lows of launching a new church of ragamuffins (House for all Sinners and Saints).

I particularly enjoyed the chapter in which Bolz-Weber came to expand her concept of inclusive community beyond the transgender drug addicts to the suburban businessmen and soccer moms (an influx of which inundated the service after her church attracted some media attention). In short, Bolz-Weber started off as a pastor to the ragamuffins. Then she came to see how we’re all ragamuffins.

While Pastrix is worth reading, I admit that I remained underwhelmed. Perhaps you can chalk up my reaction to the tyranny of high expectations. But it seemed to me that the book’s primary distinguishing feature was not penetrating wisdom and insight, but rather the novelty of a bold, irreverent female progressive pastor who curses … a lot. Here’s an example:

“when I’ve experienced loss and felt so much pain that it feels like nothing else ever existed, the last thing I need is a well-meaning but vapid person saying that when God closes a door he opens a window. It makes me want to ask where exactly that window is so I can push him the fuck out of it.” (83)

Perhaps many readers also want to “push God the fuck out of a window” or maybe they are just intrigued to read a pastor saying it… and not getting hit by lightning. But I guess I’m just more traditional in that I prefer my swears in a Martin Scorsese film.

Okay, that’s not entirely fair. It is probably more correct to say that the real draw of Pastrix is that Bolz-Weber defies categories in general. For example, a blurb from The Washington Post on the back cover describes her as representing “a new, muscular form of liberal Christianity.” That would be noteworthy, but the fact is that Bolz-Weber is not really a liberal. Consider, for example, her smackdown of Unitarianism (45). Granted, Bolz-Weber minimizes the importance of doctrine like many liberals (15), but it seems to me that is owing not to “liberalism” but rather to Lutheranism. In short, like Luther, Bolz-Weber offers a theology of crisis focused not on scholastic details but rather on the sinner justified before God. And that rightly gets people’s attention.

While I can’t say I connected with Pastrix at a deep level, I was sufficiently intrigued that I decided to check out some of Bolz-Weber’s sermons. I particularly appreciated in the book how she described her bond with her loving husband Matthew (married in 1996) and their two beautiful children.

So I decided to give a few of Bolz-Weber’s recent sermons a listen. A few minutes into the first sermon, Bolz-Weber casually recalled a conversation she’d recently had with her non-Christian boyfriend. Non-Christian boyfriend? I paused the recording and went online. Sure enough, Bolz-Weber and her husband Matthew had divorced two years ago. And she was now apparently dating a non-Christian.

I never finished the sermon.

You can purchase Pastrix here.

The post Pastor to the Ragamuffins: A review of Pastrix appeared first on Randal Rauser.

June 30, 2018

Are same-sex relations and menstrual intercourse moral abominations? A Response to Michael Brown (Part 2)

In this article, I continue my response to Michael Brown’s response to my review of Brown’s book Can You Be Gay and Christian? The topic in this installment is Brown’s response to the second part of my review. (You can read that part of my review here.)

Let me begin with a quick summary of the claim under contention. While the Hebrew categorization of “to’evah” can identify ritually impure actions, Brown argues that in the case of Leviticus 18 and 20, it identifies immoral actions which are intrinsically wrong. Given this assumption, when homosexual intercourse is condemned in 18:22 and 20:13, it follows that these prohibitions should be interpreted as absolute moral condemnations rather than limited and culturally relative ritual impurities.

In my response, I point out that sexual intercourse during menstruation is also condemned as to’evah in Leviticus 18 and 20 (18:19 and 20:18). The problem is that there doesn’t seem to be anything intrinsically immoral about menstrual intercourse. On the contrary, it would seem that the prohibition of this action should be interpreted in terms of ritual impurity.

The point I’m making can be construed as a reductio ad absurdum. (A reductio is an argument in which a premise is assumed for the sake of argument in order to demonstrate that it has implausible consequences which are sufficient to warrant rejection of the premise.) Here’s the argument:

(1) All actions classified as to’evah in Leviticus 18 and 20 are immoral. (Premise for reductio)

(2) Menstrual intercourse is classified as to’evah in Leviticus 18 and 20.

(3) Therefore, menstrual intercourse is immoral.

(4) But menstrual intercourse is not immoral.

(5) Therefore, the classification of an act as to’evah in Leviticus 18 or 20 does not entail that the act is immoral.

To be sure, the act may nonetheless be immoral. The simple point is that inclusion in the prohibition lists of Leviticus 18 and 20 is insufficient to establish this conclusion.

Here is Brown’s response:

https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/tentativeapologist/Brown+Part+2.mp3

* * *

Brown makes several points here.

To begin with, he notes that some scholars like Robert Gagnon agree that not all acts condemned in Leviticus 18 and 20 are immoral: in particular, the condemnation of menstrual intercourse is ritual in nature.

But Brown does not take that view. Instead, he believes that the condemnation of menstrual intercourse is indeed immoral. Thus, he rejects (4). However, he seems to take the view that there are degrees of immorality and menstrual intercourse is presumably low on that scale. By contrast, however, homosexual intercourse is identified as especially detestable in these prohibitions. In other words, it is seriously immoral.

Further, Brown points out that homosexual intercourse is so problematic that the Torah assigns the death penalty for offenders. However, it is worth noting that not every action to which the Torah assigns the death penalty appears to be seriously immoral. Consider, for example, the prescription that non-Levites who approach the Tabernacle should be executed (e.g. Numbers 1:51).

Finally, Brown notes that the NT reiterates an absolute condemnation of homosexual intercourse, thereby placing it clearly in the arena of moral rather than mere ritual prohibitions.

To sum up, the Torah condemnation of menstrual intercourse can be interpreted as a ritual impurity (as with Gagnon) or a moral indiscreation (as with Brown). But if it is interpreted as the latter, it is a relatively low moral offense. Nonetheless, Brown’s position remains problematic for those who insist that there is no moral offense at all in the act.

The post Are same-sex relations and menstrual intercourse moral abominations? A Response to Michael Brown (Part 2) appeared first on Randal Rauser.

June 28, 2018

Overcome your Cognitive Bias with the 50/50 Rule

In the past, I have often lamented the way that people exhibit cognitive biases in their critical engagement with opposing views. I have especially noted how Christian apologists are prone to do this (as in this critique of Andy Bannister and this critique of Paul Copan).

But this isn’t just about Christians: non-Christians do it as well. Indeed, for all their talk of “reason” and “evidence,” atheists appear to be as prone as anyone to exhibit bias and caricature the beliefs of others. (In this article, I illustrate how both Christians and atheists caricature their opponents.) In other words, neither believing in God nor disbelieving in God bestows epistemic virtue. Rather, you need to work at it.

In the past, I have also offered a simple but challenging solution: the golden rule. At times, I have adopted the more unwieldy phrase the “golden rule of hospitable dialogue” but the idea is simply this: treat the views of others the way you’d like the others to treat your views. In short, if you want other folks to steelman your views rather than strawman them, then for goodness sake, steelman the views of your interlocutor rather than strawmanning them! This ain’t rocket science.

I often encounter people who insist that they really do this when, in fact, they don’t. (It’s the same old story: we think we’re far more virtuous than we are. Self-serving bias is a killer.) So here’s my question: how can we encourage more people to develop the discipline of the golden rule in their interactions with others? What practical advice might one follow? To that question, I offer a simple and concrete solution. I call it the 50/50 rule:

50/50 rule: devote as much time to (a) defending the beliefs of your opponents and critiquing your own beliefs as you devote to (b) critiquing the beliefs of your opponents and defending your own beliefs.

The problem is that it is natural to focus on (b) and to neglect or completely ignore (a). Do that long enough and you become deeply entrenched in your cognitive biases. So the best solution to breaking out of that vicious cycle is to be intentional about redressing your own biases by intentionally pursuing the defense of the beliefs of others and the critique of your own beliefs.

The post Overcome your Cognitive Bias with the 50/50 Rule appeared first on Randal Rauser.

June 27, 2018

Gay-Affirming Christians and Charismatics: A response to Michael Brown (Part 1a)

I didn’t quite get through my response to the first part of Michael Brown’s rejoinder in my previous article, hence the continuation of part 1 in this article.

In my original review, I noted that Brown attempts to argue that gay-affirming Christians errantly allow their experience to shape their reading of the Bible and understanding of doctrine. I wrote:

“As Brown puts it, gay Christians begin with their gay identity and then read the Bible through the lens of that experience.”

My response was to point out that gay-affirming Christians are not the only ones who use experience as a theological criterion. I wrote:

“The problem with this kind of argument is that charismatics also draw upon experience in theological reflection, in particular the experience of the Holy Spirit.”

I referred to charismatics in my example knowing that Brown himself is a charismatic. My point here was not to exonerate gay-affirming theological method because I concede that experience can be used improperly as a source of theological reflection. My point was simply that saying a particular individual (whether gay or charismatic or anything else) appeals to experience in their theological reflection is not in itself an objection. One must go further and offer evidence that their appeal to experience is somehow problematic.

With that as background we can turn to Brown’s response. At this point, you can advance the audio to 5:28 in the clip and listen for the remaining two minutes:

https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/tentativeapologist/Brown+Part+1.mp3

* * *

Let’s start with the fact that Brown mischaracterizes my description of his position. As he puts it, my challenge is this:

“aren’t I [that is Brown] as a charismatic or Pentecostal putting my experience first?”

But that is not what I am claiming at all. Indeed, this all-or-nothing description is a strawman of my challenge. Rather, what I’m saying is simply that Brown, as a charismatic, appeals to charismatic experience as one factor in his formulation of doctrine.

If Brown wants to deny this then he is cutting himself off from the roots of the Pentecostal tradition which was unapologetic about affirming the Pentecostal doctrine of a second blessing, and tongues as the sign thereof were based on the experience of the people of Azusa Street. It was this experience which then justified using Acts as a normative text to interpret 1 Corinthians 12-14.

My point is thus that gay-affirming Christians do the same thing. Consider the hypothetical case of conservative Baptist pastor Joe Jones and his wife Marsha. The Jones are convinced that homosexuality is an abomination. But then their son comes out of the closet and reveals his deep struggles with same-sex attraction since his childhood. Now he is in a committed, monogamous, same-sex relationship Eventually Joe and Marsha meet their son’s companion, and Joe and Marsha slowly recognize that the young couple seems to have a loving and faithful relationship, one that demonstrates the best virtues of heterosexual relationships.

Eventually, the Joneses come to read the Bible differently based on their experience of their son. They have clearly used experience as a theological criterion in their own doctrinal formulation. My point is simply that this is not different in kind from what Pentecostal and charismatic Christians do when they move from their experience of the Spirit to new readings of the biblical text.

Brown, however, claims that he doesn’t use experience as a theological criterion. He just uses the Bible which, so he claims, clearly supports his point of view. Thus, he declares:

“from Genesis to Revelation we can point to a consistent pattern of God’s miraculous intervention.”

Unfortunately, Brown has committed the fallacy of equivocation here. The question is not whether the Bible teaches that God has engaged in “miraculous intervention.” Cessationists and charismatics both agree that he has. The question, rather, is whether God grants (1) a Spirit baptism subsequent to conversion or whether (2) God gives supernatural sign gifts to Christians today. And those claims are not obviously taught in scripture. Indeed, I’d say scripture explicitly contradicts (1) and underdetermines (2).

But Brown is not willing to concede that he draws on experience as a source of theological reflection. Instead, he declares,

“If I never saw anybody healed I would teach healing because I see it in scripture.”

I don’t know whether this statement is true or not. What I do know is that it is irrelevant. You see, this statement is talking about counterfactual doctrinal formulation. But I’m not interested in speculating on counterfactuals. Rather, I’m concerned with actual doctrinal formulation such as it is. And the fact remains that in the actual world gay-affirming Christians and Pentecostal/charismatic Christians both appeal to experience as a criterion in their theological reflection.

Consequently, it is, to say the least, ironic for a Pentecostal/charismatic to impugn gay-affirming Christians for echoing a Pentecostal/charismatic theological method.

The post Gay-Affirming Christians and Charismatics: A response to Michael Brown (Part 1a) appeared first on Randal Rauser.

June 25, 2018

Okay, so Laura Ingalls Wilder was a racist. Now what?

I grew up reading Laura Ingalls Wilder’s books. (Not quite, actually. I stopped reading them when I was about 12, but they were definitely pivotal in the early years!)

The same is true of my daughter. Like me, she developed her love for literature beginning with that little house in the big woods.

So we were both surprised to learn that the Association for Library Service to Children has decided to rename the prestigious Laura Ingalls Wilder Award for children’s literature with this milquetoast moniker: the “Children’s Literature Legacy Award.”

The reason for the redubbing? The committee flagged a disturbing undercurrent of racist cultural imperialism against indigenous peoples which runs throughout Wilder’s books. (Source)

I’ve got mixed feelings about this decision. On the one hand, after the initial shock I read some sample excerpts of the deeply racist attitudes that inhabit the world of Little House on the Prairie. And I agree that there’s no escaping it: Wilder’s bucolic books do harbor some deeply unsettling racist attitudes.

But does that mean we should expunge Wilder’s name from a children’s literature prize in favor of a milquetoast moniker like the “Children’s Literature Legacy Award”? After all, Wilder has never been celebrated for her racism. She has been celebrated for the literature itself. Should the fact that this literature carries a racist tint in the same manner as countless other relics of the early twentieth century thereby render Wilder’s name verboten for a literature prize today?

As I mull this question, I find myself thinking about Martin Luther King Jr. As we now know, the man himself was a deeply flawed individual, one who engaged in multiple affairs with various women. Perhaps, as recently released FBI files claim, he even engaged in sexual orgies. Does that mean that we should expunge his name from all awards and acknowledgments concerning the civil rights movement?

I presume not. But then why should Laura Ingalls Wilder be expunged from a children’s literature award? Frankly, I suspect the problem is that her name never attained the mythos of Martin Luther King, Jr. If it had, I suspect this committee would have been more forgiving of her inevitable moral failings.

The post Okay, so Laura Ingalls Wilder was a racist. Now what? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

Is gay culture necessarily promiscuous? A response to Michael Brown (Part 1)

A few years ago, I posted a four-part review of Dr. Michael Brown’s book Can You Be Gay and Christian? A couple of weeks ago, on June 11th, Brown responded to my review on his nationally-syndicated radio show The Line of Fire. He later stipulated to me that he intends to offer a fuller response to my review in written form.

That said, I thought it worthwhile to devote some time responding to his points in response to my four-part review. In this article I provide an initial response to the first of Brown’s four-part commentary.

To begin with, as backup information, here is a link to the first installment of my four-part review for it is this article to which he is responding in the audio clip. Suffice it to say that in this article, I argue that Brown is susceptible to the charge of cherrypicking data in order to illustrate the moral debasedness of gay-affirming Christianity.

And here is Brown’s first response:

https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/tentativeapologist/Brown+Part+1.mp3

* * *

Brown’s thesis is summarized well in these words: “something’s wrong with the tree. That’s why it’s producing bad fruit.”

That may be so. The examples that Brown provides of grossly sexualized and promiscuous interpretations of the Bible and Christian doctrine certainly reflect a troubling trend. The question is whether Brown establishes a necessary link between gay-affirming Christianity and this kind of result.

Brown responds to the cherry-picking charge by emphasizing that the data he marshalls is not simply a trend: rather, it is, in his words, “pervasive”.

However, I’m not so sure. For example, I recently read an essay in the National Post written by a gay man in support of newly elected conservative premier Doug Ford’s decision not to attend Toronto’s famed gay pride parade. Josh Dehaas writes:

“Some on the left have claimed Ford’s description of Pride as an event where “middle-aged men with pot bellies” run down the street “buck naked” was evidence of homophobia. I’d say that was just an accurate description of what goes on. Disturbingly, more and more parents are bringing young children to watch the parade, exposing them to provocative displays of sexuality that no child should witness. If a politician believes in family values, why would he or she want to be associated with such debauchery?”

Why, indeed? As a person who has long deplored the licentious sexual exhibitionism of many gay pride parades, I applaud Dehaas’ frank analysis. And I share his opinion: this is not indicative of family values.

But who says that the sexual exhibitionism of the gay pride parades defines the gay community, still less the gay-affirming Christian community? Brown anticipates the response and he counters as follows:

“Now it’s true that many conservative quote ‘gay Christians’ are embarassed by this material, but its pervasive nature cannot be denied.”

I’m not so sure.

The problem is that a critic could charge Brown with confirmation bias. In short, while his book ably summarizes instances of licentious and outrageous gay theology and culture, he does not enumerate the many instances of gay-affirming Christians who affirm the traditional commitment to monogamy and the limitation of sexual expression to a covenant marriage relationship, but who also allow for the possibility of same-sex covenant marriages.

For example, Justin Lee, one of the leaders of gay-affirming Christianity, begins an influential essay on same-sex marriage by writing:

“I’m fairly conservative in my theological views. I believe that the Bible is morally authoritative, that sex is for marriage, and that promiscuity is harmful to everyone involved.” (source)

If Brown had comprehensively documented all the Christians who hold views like Justin Lee, one suspects the trend toward licentious gay-affirming Christianity would not, in fact, be quite so pervasive.

But let’s set that point aside and grant, for the sake of argument, that the licentious position is indeed pervasive. We still face this question: how “pervasive” does a belief or behavior need to be within a particular community before one has established a necessary link between that belief/behavior and that community? Simply reiterating that the belief/behavior is pervasive does not establish a necessary link because that pervasiveness could arise from a range of incidental socio-historical causal factors.

Consider the following illustration to make the point. Two centuries ago American Christianity was shaped by deeply racist pro-slavery views. These views were defended by major Christian theologians, they were assumed by denominations, and they were written into the DNA of countless congregations and preachers. To put it bluntly, a sampling of American Christianity of the time would suggest a pervasive link between Christianity and a pro-slavery position.

Now imagine a critic of Christianity two centuries ago arguing that this pervasive relationship between American Christianity and the institution of slavery reveals a necessary connection such that any person who is consistently Christian will, eventually, also endorse slavery.

Clearly, this would be a faulty argument. Instead, we could identify a range of incidental socio-historical factors that led to a pervasive link at that place and time between Christianity and the pro-slavery position.

By the same token, if we grant a pervasive link between gay-affirming Christianity and licentious behavior/tendentious exegesis, it could nonetheless be the case that this link exists due to a range of socio-historical factors.

[For example, it is a well-known fact that reform and liberation movements often begin as more radical as they seek to challenge the status quo. But over time they gradually become more socially conservative and institutionalized. Those well-known social dynamics could explain at least some of the radical trends in the LGBT community as inconoclastic challenges to ‘heteronormativity’ which will soften over time.]

So here’s the question again: is gay-affirming theology necessarily linked to the kind of licentious and debauched behavior that Brown ably describes? Personally, I don’t know. My purpose here is not to claim that it isn’t. Rather, my purpose is simply to point out that Brown has not established that it is.

To sum up, while Brown has surely identified a troubling trend in contemporary gay-affirming Christianity, I don’t think he has adequately defended himself against the cherry-picking charge. Thus, he has not established that there is a necessary link between gay-affirming Christianity and licentious behavior/tendentious exegesis.

The post Is gay culture necessarily promiscuous? A response to Michael Brown (Part 1) appeared first on Randal Rauser.

June 22, 2018

The Bible depicts God commanding moral atrocities. Should we believe it?

The Bible includes some descriptions of divine action which are fundamentally at odds with the moral perceptions of properly functioning human beings. In some cases, God is presented as performing actions that appear to be wicked. In other cases, he is presented as commanding humans to perform actions that appear to be wicked. Of the latter, the single most disturbing passage is arguably found in 1 Samuel 15:3 in which God commands Saul to kill all the Amalekite people as well as their domesticated animals:

3 Now go, attack the Amalekites and totally destroy all that belongs to them. Do not spare them; put to death men and women, children and infants, cattle and sheep, camels and donkeys.

The moral offense of this passage should be obvious to everyone. But if it isn’t, consider how you would react upon reading those directives in the Qur’an or any other extra-biblical source. In all those cases, the Christian’s moral indictment of the directive would be immediate and unqualified. Thus, at the very least, the Christian must concede that 1 Samuel 15:3 appears to present God as commanding wicked actions.

This leaves the Christian with two basic options.

Option 1: deny that the action in question is necessarily wicked.

Option 2: deny that God ever commanded the action in question.

Growing up in the church, we didn’t discuss these passages. (I talk about this problem in What’s So Confusing About Grace?) That left us with the apparent default conclusion that Option 1 was the only game in town. And that, as you can imagine, was a source of deep cognitive dissonance.

One thing I’ve discovered over the last ten years (the time that I’ve devoted particular attention to this problem) is that from Gregory of Nyssa to Greg Boyd, many Christians have explored and defended option 2.

Suffice it to say, no Christian should believe Christian discipleship requires them to deny the most fundamental dictates of their own conscience. And if that requires a Christian to embrace Option 2, then so be it. After all, the core of Christian belief belongs to a special set of doctrines like the Trinity, incarnation, and atonement. The option 1/2 debate is well outside that core.

Some years ago (six, to be exact) I wrote a couple articles (see here and here) in which I argued against Option 1 by invoking a comparison between devotional killing of non-combatants (the kind of action we find described in 1 Samuel 15:3) and devotional rape. I’m now going to close with a succinct presentation of the argument. The argument focuses in particular on a subset of the actions described in 1 Samuel 15:3, namely hacking apart healthy infants.

Why “hacking apart”? Compare 1 Samuel 15:33 which concludes with Samuel cutting Agag, king of the Amalekites, into pieces. Though many English translations do not describe the killing, the KJV captures the literal description: “Samuel hewed Agag in pieces before the Lord in Gilgal.”

And now without further ado, the argument:

(1) It is always morally wrong to rape a woman.

(2) Raping a woman is not morally worse than hacking a healthy infant to pieces.

(3) If action (a) is always morally wrong and action (a) is not morally worse than action (b) then action (b) is also always morally wrong.

(4) Therefore, it is always morally wrong to hack a healthy infant to pieces.

(5) God would not command an action that is always morally wrong.

(6) Therefore, God did not command Saul to hack healthy Amalekite infants to pieces.

The post The Bible depicts God commanding moral atrocities. Should we believe it? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

June 20, 2018

Fundamentalist Apologetics Comes of Age: A Review of Evidence that Demands a Verdict

A reasonable facsimile of the very book that provided me with ample ammunition to fire back at the skeptics throughout high school.

Josh McDowell and Sean McDowell. Evidence that Demands a Verdict (Thomas Nelson, 2017).

Like many in my generation, I grew up with a copy of Josh McDowell’s Evidence that Demands a Verdict (henceforth, Evidence) on the bookshelf. Over the years, I frequently consulted Evidence to quell doubts and provide ammunition to fire back at the skeptics on topics like evolution and the authorship of Daniel.

Apparently, a lot of people had Evidence on their shelf because the original 1972 edition was revised in 1979 and again in 1999 (xvii). Now that we have a third extensive revision, one that adds Josh McDowell’s son Sean as a coauthor, I thought it time to return to Evidence for a closer look at the latest edition. Henceforth in this review, I will refer to McDowell and McDowell as M&M.

I have titled this review “Fundamentalist Apologetics Comes of Age”. That title reflects two facts. First, Evidence has indeed come of age in the sense that it reflects an advanced state of development: this is a massive book (798 pages plus a 74-page introduction) and it covers a dizzying array of topics in an accessible and engaging manner. For that, it should be lauded.

That said, the reader should also be aware that Evidence continues to exhibit the characteristics of Protestant fundamentalism. For some people, that may be a boon to be celebrated. But for others, it is an unfortunate fact, one that significantly qualifies the book’s otherwise laudable achievements.

Note that the 2017 edition drops the hardnosed, triumphal gavel in favor of an inquisitive magnifying glass.

Apologetics Come of Age

Let’s start with the positives. As an apologetic work approaching nine hundred pages, it should be no surprise that Evidence covers an enormous range of material. Following an extensive seventy-page introduction, the main text includes four parts: Part I: Evidence for the Bible; Part II: Evidence for Jesus; Part III: Evidence for the Old Testament; Part IV: Evidence for Truth.

But before launching into some plaudits, I must say that I find this structure deeply idiosyncratic. To begin with, the introduction includes not only a personal testimony and an introduction to the field of apologetics, but also a section defending the existence of God. On the contrary, I would think a defense of the existence of God (i.e. theistic apologetics) properly belongs as the first major section of the text proper. After all, a defense of God’s existence is not prolegomenal to Christian apologetics: rather, it is a critical part of the apologist’s work.

Meanwhile, Part IV includes foundational material on topics such as the nature of truth and the concept of knowledge which arguably do belong in the prolegomena of the introduction: after all, every subsequent argument depends on a concept of truth and the accessibility of rational belief and knowledge.

I also find the text’s treatment of key biblical issues as idiosyncratic, but since those further points are indicative of the fundamentalist biblicism of the text I will return to discuss them below.

But now it’s back to the good news. And let me begin with the fact that the book is, for the most part, very readable. This is a feat in itself because Evidence has always been distinguished by a large number of extended quotations from other sources. In my experience with earlier editions of the book, that rendered the text better suited as a reference work for various topics rather than a unified book that one might read straight through. But that was not my experience with this latest edition. Indeed, at times I found this latest edition of Evidence to rise to the level of a bonafide page-turner. Hats off to M&M for that!

One of the great attractions of the book is that it boasts an encyclopedic breadth of various apologetic topics and persons. For example, it includes an excellent survey of the biblical manuscript evidence, succinct rebuttals to leading skeptics like Richard Carrier (280-84) and Bart Ehrman (Appendix), and concise summaries of controversies both recent (e.g. the Talpiot Tomb: 293-300) and old (the mystery religions).

While we’re on the topic of mystery religions, I especially appreciated M&M’s treatment of this old canard. According to this old objection, core Christian claims of Christ’s death and resurrection are anticipated in so-called mystery religions of dying and rising gods. Hence, Christianity is best explained as a further development of these venerable legendary motifs.

In reply, M&M first point out that evidence for the mystery religions is all second-century and thus after Christ. As a result, if there is influence here, it flows from Christian belief and practice to that of the mystery religions.

Further, even if the mystery religions did precede Christ, that hardly shows they explain Christ’s death and resurrection. To make the point, M&M give an analogy. In 1898 a novel was published about a passenger ship called the Titan which sinks in the Atlantic. The novel famously bears several uncanny parallels with the later sinking of the Titanic. But nobody would think that provides a reason to question the historicity of the latter event (311).

Finally, M&M cite Tolkien’s argument that anticipations of death and resurrection could be interpreted by the Christian in terms of general revelation as “God … using the images of their ‘mythopoeia’ [story-making] to express fragments of his eternal truth.” (314) Indeed! And so, in a few pages, they offer a succinct and satisfying rebuttal to a bad (but persistent) argument against Christianity.

This mystery religions example illustrates the strength of Evidence: generally brief, clear, and reliable summaries of various arguments and responses to various objections (exceptions will be noted below, however). Among the many other topics treated we find a helpful summary of cosmic fine-tuning (lxvi-lxx), a quick refutation of the miracles of Apollonius (350-1), a survey of first-principles that one can know by rational intuition (626-30), and a summary of the Moorean shift as a fitting rebuttal to skepticism (659-60). And of course, that is but a brief sampling of the extensive list of topics addressed.

And here’s the really amazing thing. This eight-hundred-page encyclopedic survey of apologetic topics is currently a mere $20 for hardback at Amazon.com. Even more incredibly, as I write, the Kindle version is $2.42. In other words, you can have all this on your smartphone for less than a Starbucks latte!

With that in mind, I don’t mind saying that despite the significant caveats that I will summarize below, Evidence is surely one of the biggest bargains in Christendom. Everything that I’ve said thus far is sufficient reason for you to buy the book, period.

Fundamentalist Apologetics

While Evidence is most surely worth the purchase price (and then some), it is important that the reader understand the book reflects some common Protestant fundamentalist hallmarks and thus, in that sense, can be properly deemed a fundamentalist apologetic.

Too often, the word “fundamentalist” is tossed around with no definition. (As Alvin Plantinga once wryly observed, people who apply the label to others often mean nothing more than “more conservative than me.”) But fundamentalism should not be treated as a mere insult. When I use the term, I intend to signal a position that evinces a particular set of characteristics commonly associated with the Protestant fundamentalism that arose a century ago and which has remaind a significant force among North American Protestants for the last several decades. These characteristics include biblicism, biblical literalism, rationalism, triumphalism, and binary oppositionalism.

Biblicism

Before we turn to consider the charge of biblicisim, we should begin by establishing the intended scope of Evidence. In the introduction, Andy Stanley writes:

“For over forty years, Evidence That Demands a Verdict has been the go-to resource for Christ followers desiring to equip themselves for the task of presenting and defending the claims of the Christian faith.” (xv)

This is an important statement since it makes clear that the intent of Evidence is not simply to summarize some particular beliefs about the Bible; rather, the purpose of the book is to present and defend the entire Christian faith and to do so in a sprawling work of close to nine-hundred pages.

With that in mind, we face a puzzle. You see, while the book is purportedly concerned with defending the entirety of Christian faith, it has an inordinate focus (70% or 600+ pages) devoted to explicating and defending the Bible. While some of these points — e.g. the historicity of Jesus and his resurrection — are certainly core to Christian belief, others are not. Consider, for example, the fact that entire chapters are devoted to relatively arcane topics like the authorship of Isaiah and Daniel.

Not only is the book largely devoted to the Bible, but incredibly enough, the authors devote fewer than five pages to discussing the most central doctrines of Trinity, incarnation, and atonement. Now this is a puzzle: why hundreds of pages on the Bible but almost nothing on essential Christian doctrines?

The answer, so I believe, is found in the influence of biblicism. I understand biblicism to represent a view that eschews the critical role of communal tradition in articulating Christian faith in favor of a belief that the Bible alone remains the source and norm of theological belief and Christian life.

The biblicist tends to downplay the post-biblical development of doctrine within the church as well as the extent to which extra-biblical sources (e.g. reason, tradition, experience, community, culture) played in the articulation of doctrine. On the contrary, the biblicist tends to understand the core doctrines that define Christian identity as existing in latent form in the Bible. And thus, the relevant verses only need to be identified and their implications unpacked in order to have a sufficient definition of various Christian doctrines.

This biblicist mindset is famously illustrated in the methodology of Gordon Lewis, Decide for Yourself: A Theological Workbook. And so, for example, in order to articulate the doctrine of the Trinity one can bypass the history of doctrinal debate and creedal development and instead focus simply on the exegesis of a narrow set of biblical texts.

If you can defend the Bible (and the chapters on Isaiah and Daniel are devoted to defending the traditional authorship so as to retain the veridical force of their future-prophecies) then all the rest, including major Christian doctrines unfolds naturally. As M&M write, the doctrine of the Trinity is “Rooted deeply in the pages of Scripture” (7).

But the reality is far more complicated. Christian doctrines are not simply read out of the Bible. Nor are they derived from the Bible by some theological analogue to Baconian induction. Rather, they are theoretical interpretations of scriptural data that unfolded over centuries as the church wrestled with the biblical text and their own communal and individual experience in light of the best philosophy and culture of their day.

Perhaps Evidence might be forgiven for failing to exposit major Christian doctrines: after all, it is an apologetic book, not a work of theology. But then, the book also omits any apologetic defense of major Christian doctrines despite the fact that each of them is subject to significant objections. For example, critics have argued that the doctrines of the Trinity and incarnation are incoherent; they’ve insisted that atonement is immoral; they’ve claimed that divine foreknowledge is inconsistent with human free will; they’ve warned that an eternity in heaven would be insufferably boring and an eternity in hell inexplicably cruel.

These and countless other objections have been offered to specific Christian doctrinal claims, and yet Evidence, an eight-hundred-page book ostensibly devoted to defending “the claims of the Christian faith”, discusses none of them even as it devotes entire chapters to the authorship of Isaiah and Daniel!

Biblical Literalism

The second theme that I want to highlight is biblical literalism. This is is a distinctive hallmark of fundamentalism according to which the default interpretation of a biblical text is a literal interpretation. And what exactly is the literal interpretation? The concept is commonly associated with a plain or straightforward reading of the text.

So far as I can see, M&M never explicitly endorse literalism as a formal hermeneutical principle (though many fundamentalists have). Nonetheless, I believe that the fingerprints of biblical literalism are found throughout the book. Consider, for example, these passages:

“The straightforward way of reading the Bible is that Adam was a historical person.” (441)

“a straightforward reading of the details in the book of Exodus leads a reader to recognize the text is being presented as an authentically historical account, not mythology.” (462, emphasis in original)

I understand why a modern reader would assume that particular readings of the biblical text are obvious or plain or straightforward and thus how any interpretation which deviates from this obvious, plain, straightforward reading is automatically suspect.

However, too often the fundamentalist assumes that plain and straightforward to the ancient Israelite or first century Christian is just the same thing as plain and straightforward to the twenty-first century North American fundamentalist.

It isn’t.

And who decides what is straightforward? Is six 24 hour days the straightforward reading of Genesis 1? What about a literal thousand year millennium in Revelation 20?

Chapter 17 and its discussion of the historical Adam is particularly illuminating. The chapter is deeply influenced by the Zondervan book Four Views on the Historical Adam which features a debate between a young earth creationist, an old earth creationist, and two theistic evolutionists (John Walton and Denis Lamoureux).

To their credit, M&M engage with Walton and Lamoureux. Nonetheless, their engagement struck me as superficial and perfunctory, a necessary stop on their way to affirming old earth creationism.

This is particularly unfortunate because this topic could have provided an ideal basis to challenge benighted Bible readers to come to terms with the extent to which the cosmology of the biblical authors assumes obsolete categories such as the raqia (firmament), the chaos monsters, and the three-storied universe itself. (For further discussion, see my review of Robin Parry, The Biblical Cosmos.)

To sum up, M&M could have done their readers an enormous service by equipping them with a sophisticated and nuanced concept of divine accommodation rather than retaining the awkard concordism that so often characterizes fundamentalist approaches to the Bible and science.

Rationalism

The word “rationalism” can mean many things. Here I am using it to flag two themes in Evidence: a commitment to biblical propositionalism and biblical inerrancy.

Propositionalism reflects the idea that the essence of biblical revelation is found in the communication of propositions, in other words, statements about God and our relationship to him. In short, for the propositionalist, the Bible is primarily an information transfer rather than an experiential, transformative text.

M&M write: “We … believe that Scripture certainly conveys propositional truths, and symbolic truths at times, through texts that are factually correct.” (587) While there are many literary expressions in Scripture that are not propositions (e.g. commands, questions), nonetheless, M&M cite Geisler and Roach as saying that “all truth in the Bible is propositionalizable.” (Cited in 587)

This notion of Scripture as a mere repository of facts was famously defended by Carl Henry, but to non-fundamentalists it reflects a gross reductionism. Scripture is, first of all, a transformative encounter and the reading of and submission to it should not simply convey facts but yield transformation (2 Timothy 3:16-17). Hence, we have Karl Barth’s famous invitation to the strange new world in the Bible.

Given their commitment to the Bible as a repository of propositions, it is no surprise that M&M also affirm biblical inerrancy. Indeed, they apparently believe that inspiration entails inerrancy:

“Since we believe that the Bible is God’s Word and are therefore committed to the inerrancy of Scripture, we believe that alleged contradictions are not real, and that the Bible truly does harmonize when properly understood.” (586; see also their endorsement of the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, 122-23)

The inerrantist may be able to reconcile the two seemingly contradictory accounts of the death of Judas (70), but how do they propose to reconcile Ezekiel 18:23 with Psalm 37:13? No doubt, they will try. But what if this entire approach to the Bible misses the point (Gen. 32:28)?

Triumphalism

According to apologetic triumphalism, there are no major unanswered objections to Christian faith and there is rationally compelling evidence for Christian belief. Fundamentalist apologetics have a long history of triumphalism which is often buoyed by the assumption that those who disagree with them are irrational and/or immoral. (See, for example, my discussion in Is the Atheist my Neighbor? as well as chapter 1 of my book Theology in Search of Foundations.)

I do want to give M&M some credit here as early on they have a good discussion on the importance of character and conduct (liv-lvii). So even if they are triumphalistic, they’re not going to rub it in!

At the same time, as I read through Evidence I found that M&M often overplayed their hand. For example, at several points, they move from mere possibility to plausibility (see, for example, their discussion of the virgin birth). At the same time, they completely skirt some of the most troubling objections to the Bible (e.g. biblical violence) and Christian faith more generally (see my comments above on Christian doctrine).

Particularly revealing is their discussion of prophecy in chapter 9: “Old Testament Prophecies Fulfilled in Jesus Christ.” Fundamentalist apologists have a very bad history of naively prooftexting biblical prophecies to establish allegedly rationally compelling evidence for the supernatural origins of the Bible. Initially, it seems that M&M are going to avoid these perils as they acknowledge the literary/typological function of prophecy (e.g. 211).

But then everything changes with the section: “Summary of Old Testament Predictions Literally Fulfilled in Christ” (229-31). Here they quote a fellow named Peter Stoner who does some mathematical calculations on fulfilled prophecy. Stoner concludes, “We find the chance that any one man fulfilled all 48 prophecies to be 1 in 10157. This is really a large number and it represents an extremely small chance.” (231)

Um, yeah.

In other words, the cautionary hermeneutical lessons from earlier in the chapter are suddenly forgotten as we fall back into the worst of fundamentalist bad Bible reading and misbegotten triumphalism.

Binary Oppositionalism

Fundamentalists have a long history of drawing stark binary oppositions between the in-group (i.e. conservative Protestant Christians) and the out-group (i.e. “the world”). M&M provide fodder for those regrettable tendencies. Notably, they frequently invoke language which seeks to sow mistrust in the reader of all scholarship that is not adequately conservative. For example, they warn that

“One must recognize that presuppositions and biases exist in the scholarly world. Not infrequently, these predilections create blind spots and gaps in research and publication….” (418-19)

I don’t disagree with this caveat: scholars can have biases. The problem is that M&M repeatedly warn about the biases of so-called liberals. As they say, “the anti-Bible bias is so strong in current academia….” (419) However, it is clear that for M&M “anti-Bible” reduces to opposition to their fundamentalist and inerrantist reading of the Bible.

Consider, for example, the historicity of the Exodus (including the notion that more than a million Israelites departed Egypt):

“Throughout most of Jewish and Christian history, the exodus as a literal event has not been questioned. However, in contemporary scholarship, especially among archaeologists whose theology tends toward liberalism, the historicity of the exodus has been doubted or even disbelieved entirely.” (460, emphasis added)

Of these “liberal” scholars they write:

“We discover that often a different standard of evidence is applied to the Bible as opposed to other ancient manuscripts.” (461)

The irony is that if there is evident bias here, it is most surely with M&M and their fellow conservative (i.e. evangelical and fundamentalist) scholars. Note that M&M frequently endorse highly idiosyncratic positions because of their theological conservatism including Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch (5), Isaian authorship of Isaiah (chapter 24), and Pauline authorship of Hebrews (32; but see 183). Not surprisingly, they offer no caution to the reader to look for the biases that underlie their own approach to the data. Instead, we are only given warnings to be suspicious of the majority opinions of “liberal” scholars.

This tendency of M&M to impugn bias and nefarious motives to non-conservatives is an example of poisoning the well. Perhaps the ugliest expression of the practice occurs when M&M attempt to tar the Documentary Hypothesis with the brush of anti-Semitism (540). To be sure, anti-Semitism is an ugly thing but whether or not Wellhausen was anti-Semitic has precisely no bearing on assessing the veracity of the Documentary Hypothesis.

At the end of the book, M&M devote chapters to discussing postmodernism and skepticism. However, rather than explore how one might critically engage these ideas with charity and nuance (e.g. by considering how the postmodern incredulity toward metanarratives may illumine a Christian epistemic humility), they feel compelled to offer unqualified rebuttals. And so we get confrontational chapter titles: “Answering Postmodernism” (645) and “Answering Skepticism” (662).

Perhaps the very worst example of binary oppositionalism in the book is found in M&M’s concluding comments on skepticism:

“All versions of skepticism have a similar goal: calling knowledge into question. Note that this intellectual goal is not the same thing as biblical discernment, which is ‘the ability to judge wisely and objectively.'” (662)

This is absurd. As Anthony Kenny once observed, reason itself is the golden mean between skepticism (i.e. the tendency to doubt) and credulity (i.e. the tendency to believe). And the same goes for discernment. It is no substitute for skepticism. Rather, it is an expression of reason which includes skepticism.

So why do M&M demonize skepticism in all its expressions? I suspect this reflects a tendency to retrench belief within the conservative Christian community. Alas, this kind of binary oppositionalism sustains conformity of belief at the cost of critical thinking.

Fundamentalist Footnotes

Not every vestige of fundamentalism evident in the book can be explicated as a running them. At several points, M&M evince other common characteristics of fundamentalism. For example, in their efforts to strengthen their position, fundamentalists frequently caricature or otherwise misrepresent the beliefs of others. As a case in piont, consider M&M’s claim that according to Judaism, people are saved by “the Law” (xlv).

Fundamentalists have also tended to be hostile to and dismissive of the Roman Catholic Church. I wouldn’t accuse M&M of hostility, but they most certainly are woefully dismissive, most obviously in their trite rebuttals to the Apocrypha (38-40). For example, M&M quote the following argument from Ralph Earle for rejecting Second Esdras:

“Second Esdras (AD 100-200) is a collection of three apocalyptic works containing seven visions…. Martin Luther was so confused by these visions that he is said to have thrown the book into the Elbe River.” (38)

That’s it: the sole reason for rejecting Second Esdras. This is a bald case of special pleading. If we are to reject Second Esdras because Martin Luther found it confusing, then why keep Revelation?

Next up, we have the fundamentalist commitment to tract-based conversionist evangelism: believe it or not, the final four pages of Evidence (795-98) are devoted to a summary of Bill Bright’s Four Spiritual Laws.

Finally, fundamentalists tend to be complementarians and to employ patriarchal and gender-exclusive language. With that in mind, note that M&M employ “man” and “mankind” throughout the text (e.g. 10; 199; 224; 384; 387; 425; 428; 429; 430, etc.). This might seem like a small matter to the lay reader. But within the academy, the use of gender-inclusive language (e.g. humankind; humanity) has been de rigueur for more than twenty years. Set against that backdrop, the persistent use of widely rejected gender-exclusive language is insensitive at best and an affront to gender-inclusion at worst.

The Verdict

As I observed above, not everybody is opposed to fundamentalism. To those folks, I can recommend this book without qualification, at least in the sense that I think they will find it to be beneficial without qualification.

But I don’t share that rosy picture of fundamentalism. I think its distinguishing features like biblicism, literalism, rationalism, triumphalism, and binary oppositionalism are false and harmful. And in that sense, my own commendation of Evidence most surely comes with a qualification.

Nonetheless, the virtues of the book — clear writing; encyclopedic scope; bargain price — are undeniable and that is sufficient for me to give Evidence a robust, if qualified, endorsement.

You can visit Amazon for those bargain prices here.

And my thanks to Thomas Nelson for a review copy of Evidence that Demands a Verdict.

The post Fundamentalist Apologetics Comes of Age: A Review of Evidence that Demands a Verdict appeared first on Randal Rauser.