Randal Rauser's Blog, page 92

October 1, 2018

Is the evangelical tent getting bigger?

In the second edition of their book Across the Spectrum: Understanding Issues in Evangelical Theology (Baker, 2009), Gregory Boyd and Paul Eddy offer a survey of seventeen theological issues of debate among evangelicals. That list includes the following:

biblical inerrancy

divine providence

divine foreknowledge

the interpretation of Genesis 1 (young earth view; day age view; restoration view; literary framework view)

the divine image

the incarnation

the atonement

salvation and election

sanctification

eternal security

the destiny of the unevangelized (exclusivism vs. inclusivism)

baptism

the Lord’s Supper

charismatic gifts

women in ministry

the millennium

theories of hell (eternal conscious torment vs. annihilationism)

When the second edition of Across the Spectrum was published nine years ago, I suspect a few evangelical eyebrows were raised to see topics such as “inclusivism” and “annihilationism” included as evangelical topics of debate.

But looking back from 2018, those issues are no longer surprising. Indeed, in our own day, the vanguard of evangelical conversation includes several other topics including theistic evolution, the historicity of Adam, and universalism. (In 2006, my friend Robin Parry published a book called The Evangelical Universalist under the pseudonym of “Gregory MacDonald. Parry forcefully argued that universalism — the conviction that all people will ultimately be reconciled to God the Father in Jesus Christ — is fully consistent with evangelical conviction.)

In recent years, a growing number of evangelicals (and folks from an evangelical background) have taken affirming positions on LGBT issues (e.g. Steve Chalke; Jim Wallis; Rachel Held Evans; Tony Campolo). I’m not sure at what point this trend will reach a critical mass, but judging by the current trajectory, I suspect that within the next few years, this issue will be recognized as an intra-evangelical debate. I wouldn’t be surprised if the 3rd edition of Across the Spectrum dares to include the LGBT debate.

All of this leads me to conclude with a couple of questions.

First, what do you think will be the future issues of debate within the evangelical sphere?

Second, do you think the evangelical tent will continue to expand? Or do you think a conservative retrenchment is on the horizon?

The post Is the evangelical tent getting bigger? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

The Day I Ran for the Cure

This past Sunday (Sept. 30) I participated for a fifth year in the annual CIBC Run for the Cure to end breast cancer. I set a modest fundraising goal ($300) which I exceeded thanks to the generous donations of five people for a grand total of $503. I run to honor my mom — a cancer survivor — and all others who face this nasty disease.

Here are my Sunday tweets chronicling the day:

This morning, I participated in my 5th annual #RunFortheCure to end breast cancer. It was a chilly morning … but at least it wasn’t snowing! (1) pic.twitter.com/SBUtHQqVWL

— Tentative Apologist (@RandalRauser) September 30, 2018

Apart from the run itself, the free #McDonalds coffee was definitely a highlight. (2) pic.twitter.com/ejPBJpVf2g

— Tentative Apologist (@RandalRauser) September 30, 2018

And we’re off… (3) pic.twitter.com/yeuAIWQwLE

— Tentative Apologist (@RandalRauser) September 30, 2018

Half-way through the run, I had to stop to take a selfie with my daughter, a race volunteer. You can tell that she’s like totally into getting a selfie with the old man. (4) pic.twitter.com/7lOEFw0ISS

— Tentative Apologist (@RandalRauser) September 30, 2018

Every year, my heart is warmed to see how many dogs run to end breast cancer. Man’s (and woman’s!) best friend, indeed. (5) pic.twitter.com/5Rc6lKpbZA

— Tentative Apologist (@RandalRauser) September 30, 2018

One more thing: calling the porta-potties “bathrooms” is going a bit overboard on the euphemistic language. (6) pic.twitter.com/OMEIgrCVTB

— Tentative Apologist (@RandalRauser) September 30, 2018

The post The Day I Ran for the Cure appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 25, 2018

Does Christianity need the Homoousion?

Last year, I posted an article titled “Does Christianity need a resurrected Jesus?” In this present article, I want to consider another important question: Does Christianity need the homoousion?

Alas, while we all know what “resurrection” means, the same cannot be said of homoousion, so allow me to explain. The term was invoked at the Council of Nicaea (325) as a way to identify the convictions of the emerging fourth-century orthodoxy. In direct response to (and censure of) the convictions of Arius and his supporters, the Council affirmed that Jesus is the same (homo) substance (ousia) as the Father. While the precise meaning of the term was a matter of some controversy, in subsequent theology the homoousion has been taken to be an affirmation of ontological equivalence: that is, the Son shares the same divine nature as the Father.

Now, let me be clear: as an evangelical Baptist, I accept the homoousion and recognize it as an important mark of Christian orthodoxy. That said, my concern here is to consider the validity of some of the elevated language about the doctrine’s importance that one commonly finds in Christian theologians. For this essay, my representative example will come from theologian Alan Torrance. Torrance writes:

“Put simply, if I did not believe I could affirm what is being affirmed in the homoousion, I would cease to be a Christian forthwith; I would resign from the church, from my vocation as a theological teacher, and go and do something useful!” (“Being of One Substance with the Father,” in Christopher Seitz, ed., Nicene Christianity: The Future For a New Ecumenism (Grand Rapids: Brazos Press, 2001), p. 50.)

It’s important that we are clear on what Torrance is saying here. He is not saying merely that if we reject an essential orthodox Christian claim like the homoousion that we are then obliged to leave the orthodox church that confesses this doctrine. That may be true (though it frankly depends on how tolerant your particular ecclesial communion is to divergent opinion). Regardless, Torrance’s point is far more provocative, for he is claiming that rejection of the homoousion inevitably undermines the value of Christianity entirely. Reject this doctrine and there is nothing left in your remaining Christian beliefs to sustain an existentially livable and worthwhile Christian faith.

That’s a robust claim, but is it true?

In order to test this, let’s consider a situation in which you come to believe the homoousion is false and that a competing doctrine, the homoiousion, is true. While these two terms are separated by a similar letter (iota in Greek), they convey very different doctrinal assertions: according to the homoiousion doctrine, Christ is similar to but not the same substance as the Father. To fill out the picture, you come to believe something similar to what Arius believed: namely, that God the Son is the Father’s first creation, a being the Father brought forth as the first of his works and through whom he made all other things.

The rejection of the homoousion is a big deal. But still, it is worth noting that while you would no longer believe that the Son is ontologically equivalent to the Father, you would still be a monotheist; you’d still believe that God the Son is the creator and sustainer of the world, the one mediator between God and all (other) creatures; you’d still retain a robust doctrine of creation and providence; you’d also still have your sense of justice and are committed to a cruciform ethic; and you’d look forward to a doctrine of future resurrection, posthumous judgment for those outside Christ, and the redemption of creation. Based on this extensive list of doctrines, what could justify Torrance’s claim to that loss of the homoousion would lead him to “cease to be a Christian forthwith”?

Torrance’s defense of this claim is summarized in the following quote he cites from Alasdair Heron:

“What was missing in Arius’ entire scheme was, quite simply, God himself. True, he was there—after a fashion. He was there, but he was silent, remote in the infinity of his utter transcendence, acting only through the intermediacy of the Son or Word, between whose being and his own, Arius drew such a sharp distinction. The God in whom Arius believed had no direct contact with his creation; he was for ever and by definition insulated and isolated from it in the absolute serenity of an unchanging and unmoving perfection. God himself neither creates nor redeems it; he is involved with it only at second hand.” (Cited in “Being of One Substance with the Father,” p. 53)

In this quote, Heron declares that Arius’s theology — and presumably every other non-homoousion theology — loses the unique doctrine of incarnation/immanence that is entailed by the homoousion. In other words, once you deny the homoousion, God is “involved … only at second hand.”

The problem with this kind of argument is that it is vulnerable to a tu quoque rebuttal: in other words, Torrance’s homoousion theology is likewise subject to the rebuttal that God is “involved … only at second hand” relative to other distinct conceptions of divine presence and immanence. Consider, for example, a theology of panentheism. On a panentheist theology, creation is understood to be, in some sense, God’s body. This model contrasts with Torrance’s orthodox Christian theology of creation which posits an absolute ontological distinction between God and creation.

Thus, while on Torrance’s view, the unique presence of God is mediated solely in the incarnate Son, the panentheist can claim that on their theology every aspect of creation participates in God’s being as an expression of his presence. And thus, one could claim that relative to the panentheist’s expansive conception of divine mediation, Torrance’s theology posits God’s involvement in creation “only at second hand”.

Of course, Torrance will not be bothered by this alleged diminution in the divine presence. On the contrary, he will dismiss the panentheist’s theological framing of the divine presence as tendentious and self-serving. But this is where the tu quoque enters in because the homoiousion theologian will likewise not be bothered by the insistence that denying the homoousion renders God’s involvement in creation second hand. Instead, they too will find this theological framing of the divine presence to be tendentious and self-serving.

The same issue appears within the bounds of orthodox Christian opinion. For example, some Christians claim that God is atemporal (i.e. such that temporal predicates do not apply to God). Others claim that God is temporal (i.e. such that temporal predicates do apply to God). The temporalist can argue that on the atemporalist view (a view that has been historically dominant in the Christian tradition) God’s involvement in creation is “only at second hand” through the timeless willing of temporal effects. And where the question of divine presence to creation is concerned, it seems to me that the move from homoousion to homoiousion is not obviously more radical than the move from divine temporality to atemporality.

To conclude, while I believe the doctrine of the homoousion is both true and important, we should be careful not to exaggerate that importance. The fact is that we demonstrate our care for doctrines by accurately describing their meaning and significance, not by blurring the line between accuracy and pious hyperbole.

The post Does Christianity need the Homoousion? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 21, 2018

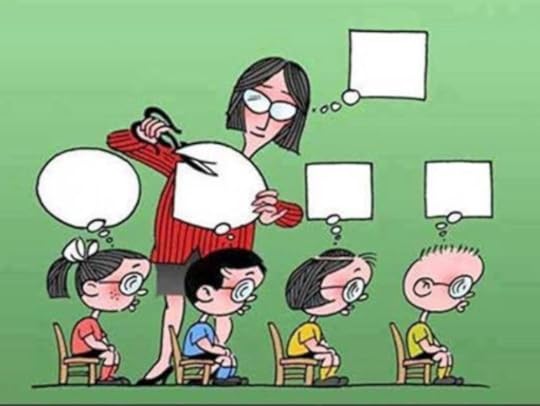

The Ways of Atheist Indoctrination

Image Credit: https://medium.com/@AspieSavant/16-ba...

Many atheists are keen to identify indoctrination within Christian (or other religious) communities. Not surprisingly, however, they typically fail to recognize the extent that indoctrination can occur among atheists. In this article, I am going to take a look at indoctrination in the contemporary resurgence of atheism known as “the new atheism.”

I can already hear the atheist retort: “Indoctrinated?! How can an atheist be indoctrinated? After all, atheism simply is the rejection of theism!”

It is true that atheism is not a unified ideology, let alone an institution. But that does not mean that self-professing atheists are automatically exempt from the danger of indoctrination. In fact, the lack of formal institution, creed, or leader may, ironically enough, cultivate a false sense of intellectual independence and liberation among atheists that can render an individual even more vulnerable to indoctrination. What is necessary for indoctrination is not a magisterium or sacred text but simply a set of beliefs that inhibit critical thought, and in this article, I will argue that the new atheism is broadly characterized with these kinds of indoctrinational beliefs.

One of the most effective ways to inure an ideology from critical appraisal is by convincing those who hold it that it is not a set of beliefs in need of defense but rather a common-sense conclusion that should be recognized by any rational person. After all, common-sense surely needs no defense! With that in mind, it is not surprising that a number of new atheists stress that atheism is precisely nothing more than good sense. This is how Sam Harris puts it:

“Atheism is not a philosophy; it is not even a view of the world; it is simply an admission of the obvious. In fact, ‘atheism’ is a term that should not even exist. No one ever needs to identify himself as a ‘non-astrologer’ or a ‘non-alchemist.’ We do not have words for people who doubt that Elvis is still alive or that aliens have traversed the galaxy only to molest ranchers and their cattle. Atheism is nothing more than the noises reasonable people make in the presence of unjustified religious beliefs.”

If atheism is simply “an admission of the obvious,” then it needs no defense. Furthermore, those people who are foolish enough to deny atheism are de facto standing in direct opposition to common-sense.

David Mills argues along the same lines when he observes:

“atheists have no obligation to prove or disprove anything. Otherwise—if you demand belief in all Beings for which there is no absolute dis-proof—then you are forced by your own twisted ‘logic’ to believe in mile-long pink elephants on Pluto, since, at present, we haven’t explored Pluto and shown them to be nonexistent.”

Like Harris, Mills aims to demonstrate that the atheist is not obliged to defend anything. Rather, in his view, atheism is simply common-sense. Meanwhile, theistic belief is manifestly absurd.

These convictions concerning the radically different status of atheism and theism effectively establish a powerful binary opposition between the irrational theist (or, as Richard Dawkins says, the “faith-head”) and the rational atheist. And that, in turn, places core atheistic assumptions beyond the realm of serious critical scrutiny. It’s critical to recognize that placing one’s beliefs beyond critical scrutiny is the most important step toward indoctrination.

In this new atheist view, the religious individual is bound by the cognitive chains of irrational dogma, while the atheist-skeptic is unencumbered by any dogmas and thus is free to countenance the evidence without bias. Consequently, new atheists could hardly be more withering in their assessment of religious conviction. The depth of the binary opposition is captured in the following statement from Robert Pirsig that Richard Dawkins quotes with approval: “When one person suffers from a delusion, it is called insanity. When many people suffer from a delusion it is called Religion.” Similarly Sam Harris describes “the history of Christian theology” as “the story of bookish men parsing a collective delusion.” And if the notion of religion as a collective delusion were not bad enough, Dawkins also claims that religion is like a mind virus which co-opts and corrupts the mind of its host like a parasite. Thus, while the atheist is supposed to be the liberated free thinker, the religious believer is enslaved to a mass, collective delusion that borders on insanity.

Not surprisingly, given that new atheists assume that the religiously devout suffer from a cognitive delusion, the reflections of religious people on metaphysical questions are to be taken with no greater seriousness than the mental patient mumbling in the corner of the sanatorium. With this assumption, atheists can dismiss with staggering glibness the entire discipline of theology. For instance, Dawkins refers to the ontological argument for God’s existence, an argument that has fascinated many of the most astute philosophical minds for the last eight hundred years, merely as “infantile.” Moreover, he claims that “the notion that religion is a proper field in which one might claim expertise, is one that should not go unquestioned. That clergyman presumably would not have deferred to the expertise of a claimed ‘fairyologist’ on the exact shape and color of fairy wings.”Needless to say, it is a waste of time to get into a debate with somebody who insists on the existence of fairies (even if they happen to claim expertise in those matters).

In the paperback version of The God Delusion Dawkins responds directly to the charge that he had been inappropriately dismissive of theology. In reply, he writes: “I would happily have forgone bestsellerdom [in The God Delusion] if there had been the slightest hope of Duns Scotus [a medieval Christian theologian] illuminating my central question of whether God exists.” Needless to say, Dawkins assumes that there is literally no hope that so eminent a theologian as Duns Scotus (the famed “subtle doctor” of the thirteenth century) could have anything enlightening to say on the question of God’s existence.

These sharp binary categories — enlightened atheist vs. irrational Christian — are effective for perpetuating atheistic indoctrination, for they allow even the most novice atheist to dismiss the most senior theologians as deluded fools and irrational know-nothings. So we have David Mills, commenting: “Nor, in my opinion, is it even possible to change the religious views of those who perceive themselves as ethically superior because they belong to the one ‘true’ religion. Their ears and eyes and minds are closed forever. No amount of science or logic will make any difference to them.” Note how Mills categorically dismisses anybody who assents to a formal religious faith as hopelessly beyond the reach of rational argument. Other examples of this strategy of marginalization are easy to find.

In his bestselling book, God is not Great, Christopher Hitchens asserts, “Religion comes from the period of human prehistory where nobody . . . had the smallest idea what was going on.” This sweeping statement allows Hitchens to conclude that “all attempts to reconcile faith with science and reason are consigned to failure and ridicule.” So the same binary opposition that enables Dawkins to dismiss theologians as idiots empowers Hitchens to ignore anybody (scientists included) who would seek to reconcile science with religion. You might as well attempt to reconcile science with alchemy.

We certainly find ample evidence for the first two dimensions of indoctrination in the new atheists given their dichotomy between “irrational faith” and “reasonable common sense”. But there is one final factor that is especially powerful in perpetuating indoctrination: the perception of a crisis situation. In short, the person facing a crisis is more apt to set aside careful nuance and embrace the security and order of stark binary categories. And that is definitely the case with teh new atheism.

To begin with, we need to understand that the new atheism is a post 9/11 phenomenon spurred on by the fear that the unchecked growth of religion will lead to increasing violence, intolerance, and oppression. This crisis justifies the new atheist in adopting a new level of stridency against religion. Dawkins thus explains his animus toward religion like this: “[S]uch hostility as I or other atheists occasionally voice towards religion is limited to words. I am not going to bomb anybody, behead them, stone them, burn them at the stake, crucify them, or fly planes into their skyscrapers, just because of a theological disagreement.”

Critics of religion like Dawkins appeal to this fear of imminent violence and oppression arising from the teeming hordes of the religiously devout as the justification for forgoing nuance and charity. (You don’t mind your ‘p’s and ‘q’s when you’re in a life-or-death struggle with the glazed-eyed religious zealot.) At the beginning of his book Breaking the Spell (the spell being religion), philosopher Daniel Dennett provides a revealing admission: “Perhaps I should have devoted several more years to study [of religion] before writing this book, but since the urgency of the message was borne in on me again and again by current events, I had to settle for the perspectives I had managed to achieve so far” (emphasis added). So presumably Dennett’s often blunt treatment of religion should be excused because he did not have the luxury of more in-depth study, given the state of crisis posed by fundamentalism.

The predictable result of new atheist indoctrination is an inability to take the views of the religiously devout person with intellectual care and charity. We find ample evidence of this in Dawkins’ book The God Delusion. For instance, Dawkins described his puzzlement with religiously devout scientists as follows: “I remain baffled, not so much by their belief in a cosmic lawgiver of some kind, as by their belief in the details of the Christian religion: resurrection, forgiveness of sins and all.” Nor can Dawkins understand those theists who believe God could have used evolution to create: “I am continually astonished by those theists who, far from having their consciousness raised in the way that I propose, seem to rejoice in natural selection as ‘God’s way of achieving his creation.’” Dawkins is even mystified that some Christians could actually be highly educated: “Why any circles worthy of the name of sophisticated remain within the Church is a mystery at least as deep as those that theologians enjoy.” Dawkins’ mystification carries over to the high levels of religious observance within the American population: “The religiosity of today’s America is something truly remarkable.”

Note the terms I italicized in these quotes: baffled, astonished, mystery, remarkable. In these less-than-subtle ways, Dawkins marginalizes the religiously devout person as a bizarre phenomenon that resists rational explanation. And this incomprehension, this inability to understand people on the other side of your comfortable binary framework, is a result of indoctrination.

Over the last fifteen years, I have engaged in extensive dialogue with atheists through written and spoken debates in books, blogs, radio and podcast exchanges and formal university debates. In that time, I have encountered a number of thoughtful and reflective atheists. But I have also encountered a disturbing number of atheists who reflect this same inability to engage with the Christian person with intellectual sophistication and charity. As one atheist candidly put it in a crass question to me following an apologetic presentation: “how old were you when you were first indoctrinated?” That is what the indoctrinated atheist mindset looks like.

Note: This article is adapted from a section of my book You’re Not as Crazy as I Think: Dialogue in a World of Loud Voices and Hardened Opinions.

The new atheism is a strident, anti-religious form of atheism that has emerged as a force in popular culture since 9/11 and which is represented by its four leaders, Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, Sam Harris, and Christopher Hitchens.

Harris, Letter to a Christian Nation (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006), 51.

David Mills, Atheist Universe: The Thinking Person’s Answer to Christian Fundamentalism (Berkeley: Ulysses, 2006), 29.

Barbara Ehrenreich, “Give me that new-time religion,” Mother Jones (June/July, 1987), 60.

Cited in Dawkins, The God Delusion (Boston: Mariner, 2008), 28.

Harris, Letter to a Christian Nation, 5.

See “Viruses of the Mind,” in A Devil’s Chaplain: Reflections on Hope, Lies, Science, and Love (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 2003), 128-151.

Dawkins, The God Delusion, 104.

Dawkins, The God Delusion, 37.

Dawkins, The God Delusion, 14.

Mills, Atheist Universe, 21.

Hitchens, god is not Great: how religion poisons everything (New York: Twelve, 2007), 64.

Hitchens, god is not Great, 64-5

Not to be outdone, Sam Harris claims that “the central tenet of every religious tradition is that all others are mere repositories of error or, at best, dangerously incomplete. Intolerance is thus intrinsic to every creed.” The End of Faith: Religion, Terror, and the Future of Reason (New York: Norton, 2006), 13.

Dawkins, The God Delusion, 318.

Dennett, Breaking the Spell: Religion as a Natural Phenomenon (New York: Penguin, 2006), xiv, emphasis added.

Dawkins, The God Delusion, 125, emphasis added.

Dawkins, The God Delusion, 143-144, emphasis added. We will look at this question of Darwinian Christians in chapter eight.

Dawkins, The God Delusion, 84, emphasis added.

Dawkins, The God Delusion, 26, emphasis added.

The post The Ways of Atheist Indoctrination appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 18, 2018

What does it mean to be evangelical? And is it worth defending?

I grew up viewing the term “evangelical” as a guarantee of quality. I believed that evangelicals were the most faithful and orthodox followers of Christ and that they offered the closest approximation of the New Testament church. But while I regularly used the term “evangelical” to identify “good” Christianity, I would have been hard pressed to give a concise definition of the term. So what, exactly, does it mean to be an evangelical?

Bebbington’s Four Hallmarks

One of the most influential definitions of evangelical comes from the church historian David Bebbington. He proposed four historic hallmarks of evangelical identity:

Conversionism: an emphasis on the importance of personal conversion.

Biblicism: a high regard for the Bible and its unique authority in conveying spiritual truth.

Crucicentrism: an emphasis on the centrality of the atoning work of Christ.

Activism: a conviction that the Gospel should be lived out through visible and socially transformative actions.

By these criteria, I was definitely raised in an evangelical church. We had it all!

Conversionism? Check. I converted at the age of five after my mom confronted me with the bald choice to follow God or the devil.

Biblicism? Check. Growing up, I proudly carried my children’s KJV Bible and later my NIV Student Bible and I studied hard to win the Sunday school Bible drills.

Crucicentrism? Check. The cross was everything, the Good News, our only hope of salvation.

Activism? Check. And I had the battle scars from street evangelism and outreach dramas performed in city park to prove it.

So that was how Bebbington defined evangelical, and by that definition, I definitely qualified!

Conversionism

However, over the last couple of decades, I have begun to reconsider these four evangelical hallmarks. Take conversionism, for example. Twenty years ago I assumed you needed to know the day you were saved in order to be saved. I remember having an earnest conversation with my university dorm-mate about this question. Though he was raised in a Christian home, went to church, and read his Bible, Pete didn’t know the day he was saved. So I spent the better part of half an hour attempting to convince him that he needed to pray the sinner’s prayer just to be sure. Pete politely declined the invitation.

These days, I’m inclined to agree with Pete: I no longer assume that you must be able to identify the moment when you were saved. Consider this illustration: if I ask Ramon the mechanic, “When is the day you became a mechanic?” he might answer: “On the day I got my first job at the local garage! I remember it well!” Fair enough. But now imagine that I ask Steve the same question, and he replies like this:

“I don’t know how to answer that. My parents say I grew up with a wrench in my hand. By the time I was eight I was fixing my brother’s bike. When I was twelve I built a go-cart with a lawnmower engine. I got my first job in a garage when I turned eighteen. So I can’t point to any single moment when I became a mechanic. I mean, I could choose a moment if you really want me to. But it seems to me that picking out any single day would be hopelessly arbitrary.’

Now imagine insisting that Steve must choose one specific day or he isn’t really a mechanic. That wouldn’t make much sense, would it? The important thing is that you know you are a mechanic, not when you became one. The same goes for Christianity. What matters is not that you know when you became a Christian but rather that you are one.

Biblicism

Eventually, I found myself reconsidering Bebbington’s other criteria as well. Evangelicals pride themselves on their view of the Bible: one of their most favored descriptions is to declare it inerrant. Indeed, for many evangelicals, the defense of biblical inerrancy has become a hill on which to die. But just what does it mean to declare the Bible inerrant?

For starters, it doesn’t mean our translations are inerrant. Not only are translations always imperfect but the moment you complete a translation, it begins growing more imperfect because language is always changing. So this much is clear: inerrancy does not reside in the compromise-ridden English translations sitting on your bookshelf.

What about the original Greek, Hebrew, and Aramaic manuscripts from which our Bibles are translated? Are they without error? That’s a good question, but we’re getting ahead of ourselves, for we don’t have access to the originals (or what scholars call the autographs). All we have are copies of copies (of copies) of the originals. And we know that these copies have some errors because they differ at various points with each other. To be sure, textual critics can still reassemble the original forms of the texts of the New Testament with a high degree of confidence. (The Old Testament is a different, and far more complicated, story.) Nonetheless, the fact remains that we don’t have the original copies.

You might reply, “Okay, the copies we have may possess errors, but at least the original copies were without error.” However, it should be pointed out that it isn’t always clear what the “original copy” would’ve been. While a short epistle like Jude or 2 John was probably written up in a single afternoon, Bible scholars believe that many books in the Bible (e.g. Genesis, Psalms, Isaiah) were composed over a long period of time–decades if not centuries–by multiple authors and editors. If that is correct, then at what point in the long compositional history of these texts did they acquire the status of being inerrant? Was there ever a single original copy of Genesis or Isaiah?

The concept of inerrancy becomes even more complex when we consider it in the context of biblical accommodation. The term accommodation refers to the fact that God meets people in their limited and imperfect understanding. For example, biblical writers regularly describe God as having very human characteristics such as becoming angry or changing his mind. Theologians today typically interpret such descriptions as anthropomorphic accommodations: in other words, God is described as being like a human being so that we can better understand him and relate to him.

These same theologians add that God does not literally become angry or change his mind because God is understood to be impassible (not subject to emotional change) and omniscient (all-knowing). Nonetheless, God allows himself to be described in these terms in order to communicate with and relate to his human audience.

If that’s true, we need to ask: did the original human authors understand that their descriptions were divine accommodations to limited human understanding? Did they always understand that God was employing anthropomorphic language to reach his human audience? If they did not realize this, then it would seem to that degree the human author was in error even while the divine author clearly was not.

It should be emphasized that these comments are not intended to constitute a rejection of biblical inerrancy. Rather, they raise the point that we need to clarify just what the doctrine means in the first place. It turns out that inerrancy is a complicated doctrine, and complicated doctrines do not typically function well as rallying cries and boundary markers. Yet, inerrancy has often been pressed into service for both those tasks, tasks for which it is not well suited.

To sum up, while I believe the doctrine of inerrancy is an important concept well worth discussing, I don’t think it serves effectively as a quick and easy way to identify real evangelicals. Nor, for that matter, is the denial of inerrancy a good way to smoke out liberals (if smoking out liberals is your thing).

Crucicentrism

What about crucicentrism? I used to think the cross was about Christ dying in our place to satisfy the divine wrath against sin. In my opinion, that’s just what atonement was: Christ dying to satisfy God’s wrath. But when I studied theology I came to recognize that this picture of satisfying divine wrath was, in fact, but one theory of atonement, a view that is typically called the “penal substitution atonement.”

It turns out that there are several views of atonement in the history of Christian theology and each view can claim its own list of biblical texts, theological and philosophical reasoning, and traditional support. It is also important to note that while the early church issued formal creedal statements at church councils to ensure agreement on doctrines like the Trinity and incarnation, they never endorsed any specific account of atonement. In short, while Christians are expected to confess that God reconciled the world in Christ, there has always been debate on how God did so.

The lesson to draw here is that being crucicentric is not the same thing as accepting the penal substitutionary theory of atonement. The Church has always encompassed various different accounts of atonement, and no single view gets exclusive rights to the claim of being crucicentric.

Activism

Finally, what about activism? As I said above, when I teenager, activism meant street evangelism and evangelistic outreaches in the park.

While evangelism is important, I blush to admit that our understanding of activism completely lacked a focus on social justice. Did I have any concern for the poor and the systems of injustice that oppress people in North America and around the world? No, not really. How about environmental stewardship? While I remember learning in high school about acid rain, ozone depletion, and deforestation, these issues were never mentioned at church. Race reconciliation? I didn’t have a clue about such matters in my ethnically homogeneous church.

And had you asked me why our church isn’t concerned with social justice, the environment, and race reconciliation, I probably would’ve answered, “that’s what liberals care about!” As if the Gospel is irrelevant for society, race, and the environment!

Conclusion

I still value the evangelical tradition greatly and I think that Bebbington’s four hallmarks represent important values worth defending. But I am no longer persuaded that evangelicals have a uniquely authoritative understanding of these hallmarks or what it means to follow Jesus. And so I am no longer convinced that seeking out the evangelical stamp is a guaranteed mark of church quality. To sum up, while I used to be very concerned with labels like evangelical and liberal, these days the label I find most important is simply this: a follower of Jesus.

This article is based on a chapter from my book What’s So Confusing About Grace?

The post What does it mean to be evangelical? And is it worth defending? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 16, 2018

Ravi Zacharias: Apologist or Fabulist? An interview with Steve Baughman

Ravi Zacharias has long been recognized as one of the most respected of Christian apologists. For forty years he has been a fixture in the firmament of the apologetic pantheon, lecturing worldwide and publishing popular books like The End of Reason and Jesus Among Other Gods. He founded RZIM International, a hugely important apologetics organization, and he has hosted radio programs including “Let My People Think” and “Just Thinking” on hundreds of radio stations. Finally, Mr. Zacharias has boasted impressive academic credentials which yield credibility to his many pursuits including an impressive status as a “Senior Research Fellow at Wycliffe Hall, Oxford.”

Ravi Zacharias has long been recognized as one of the most respected of Christian apologists. For forty years he has been a fixture in the firmament of the apologetic pantheon, lecturing worldwide and publishing popular books like The End of Reason and Jesus Among Other Gods. He founded RZIM International, a hugely important apologetics organization, and he has hosted radio programs including “Let My People Think” and “Just Thinking” on hundreds of radio stations. Finally, Mr. Zacharias has boasted impressive academic credentials which yield credibility to his many pursuits including an impressive status as a “Senior Research Fellow at Wycliffe Hall, Oxford.”

All this means that it is especially troubling that Mr. Zacharias has found himself mired in controversy for the last few years over his apparent tendency to fabulate his academic history and accomplishments. It should not need to be said that if Christian apologists don’t have credibility with their audience, they don’t have anything. In short, it is essential that Christian apologists conduct themselves above reproach, eschewing partisanship and embracing integrity and honesty above all. And that meant that I had to get to the bottom of the Zacharias case, once and for all.

To that end, I have decided to invite Steve Baughman for an interview to share his own research on the matter. And who is Steve Baughman? He is a lawyer based in the San Francisco Bay Area who has carefully documented the case against Mr. Zacharias at his website.

Please note that Steve has provided extensive links throughout the interview to corroborate his various claims.

RR: Steve, thanks for joining me to answer some questions about Mr. Zacharias. I’d like to start off by addressing the question of Mr. Zacharias’s academic credentials. To begin with, could you say something about his relationship with Oxford and Cambridge universities? How has he misrepresented his educational history with these schools?

SB: Thank you for inviting me to share my findings on this important matter. Perhaps I should start by saying that none of the facts I am about to present is controversial. Thanks to Internet archive sites like the Wayback Machine we can see what Mr. Zacharias has claimed about himself over the years even though he has now removed all of it from his online publicity materials. Given his stature, what we find is really disturbing. Fortunately, we also are finally seeing him apologizing (however tepidly) for false claims he has made about his connections to these universities.

RR: So what has he claimed?

SB: Let’s take Oxford. For years Mr. Zacharias claimed to have been a “visiting professor” at Oxford. We can see this, for instance, at his website from 2006 – 2008. A few weeks ago someone noticed a video of a speech Mr. Zacharias made to the C.S. Lewis Institute in Falls Church, VA in 2008 where he says “I am a professor at Oxford now.” These claims were simply false. The University told me in 2016 it has no record of Mr. Zacharias on their payroll and that they do not believe he has ever been an employee of theirs. I immediately told Mr. Zacharias about this. About two years and much public criticism later, in August of 2018, he admitted that he had never been a professor at Oxford.

Mr. Zacharias has made various other Oxford claims that were false or misleading. For instance, he claims in his autobiography to have been “an official lecturer at Oxford.” As we just saw, this is false, per the University. He also widely claimed to have been a “senior research fellow at Wycliffe Hall, Oxford University,” but routinely, though not always, failed to disclose that this was merely an honorary position. He even told one Christian interviewer that the senior research fellow position is “a credential with which I work in the academy.” In April of 2018, he updated his C.V. to remove misleading claims and to disclose that his Oxford title was honorary. But it took over a decade for him to do so.

RR: As I understand it, Mr. Zacharias has also made false statements about his relationship with Cambridge. Is that right?

SB: Cambridge is equally disturbing. Mr. Zacharias went to a Church of England training school called Ridley Hall for a brief “guided study” in 1990. Ridley is in the town of Cambridge but not part of the University. His supervisor told me that Mr. Zacharias was there for one term, 2-3 months. During this time he audited classes and lectures at the University of Cambridge. From this brief experience, he made the very bold claim that he is “educated in Cambridge” and that he was “a visiting scholar at Cambridge University.” We can see these claims on the author blurbs on the back cover of several of his books. In his public lectures, he frequently mentions his “studies” at Cambridge. The University of Cambridge confirmed that he was never one of their visiting scholars and Mr. Zacharias quickly removed the claim from his website. That was the proper thing to do, but even here he did it in a troubling way by stating that Ridley Hall had been more closely affiliated with the University in 1990 than it is now. In personal correspondence with me, the University confirmed that this is false. Sadly, we see here that even in correcting himself Mr. Zacharias is willing to mislead.

Mr. Zacharias also widely claimed to have studied quantum physics that semester under the renowned Cambridge physicist, Dr. John Polkinghorne, to whom he refers as “my professor in quantum physics.” The University confirmed, however, that Dr. Polkinghorne had actually not taught physics in 1990. He taught a divinity class on the science/theology dialogue and one on Buddhism. It appears that Mr. Zacharias audited a divinity class and turned it into the claim that he studied quantum physics at Cambridge. He can be seen making that claim over and over again in his YouTube speeches. It is most revealing that in his recent apology he does not list “quantum physics” as one of his areas during his guided study.

A few weeks ago Mr. Zacharias admitted that he had never enrolled at Cambridge.

RR: I can imagine a Ravi supporter replying that while Mr. Zacharias undoubtedly misrepresented particular aspects of his CV, it really isn’t that big a deal. How would you respond to the charge that you’re making too much of this?

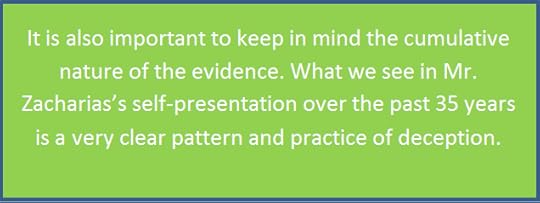

SB: A fair question. I am not aware of anyone who actually thinks that claiming to be a “professor at Oxford” when you never were is not a big deal. That is serious stuff. Nor that claiming to be “Cambridge educated” after merely auditing classes there for a semester falls within the realm of acceptable puffing. And it is hard to picture any honest person not being aghast to learn that after decades of claiming to have studied quantum physics “under” a famous scientist at Cambridge he merely audited a divinity class on the science/theology dialogue. It is also important to keep in mind the cumulative nature of the evidence. What we see in Mr. Zacharias’s self-presentation over the past 35 years is a very clear pattern and practice of deception. These may seem like strong words, but there is a preserved written record that confirms that, sadly, this is exactly what happened.

SB: A fair question. I am not aware of anyone who actually thinks that claiming to be a “professor at Oxford” when you never were is not a big deal. That is serious stuff. Nor that claiming to be “Cambridge educated” after merely auditing classes there for a semester falls within the realm of acceptable puffing. And it is hard to picture any honest person not being aghast to learn that after decades of claiming to have studied quantum physics “under” a famous scientist at Cambridge he merely audited a divinity class on the science/theology dialogue. It is also important to keep in mind the cumulative nature of the evidence. What we see in Mr. Zacharias’s self-presentation over the past 35 years is a very clear pattern and practice of deception. These may seem like strong words, but there is a preserved written record that confirms that, sadly, this is exactly what happened.

RR: Got it. So what is Mr. Zacharias’ highest earned academic degree?

SB: Mr. Zacharias has a B.A. in theology from what was once called the Ontario Bible College and a Master of Divinity degree from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. Trinity, incidentally, is highly regarded and has a rigorous M.Div program, and one of my apologist heroes, William Lane Craig, was Mr. Zacharias’s schoolmate there. In fact, they used to meet each other while taking the trash out at night. Still, Trinity informed me that its M.Div is and always has been a non-academic degree. So we see that Mr. Zacharias actually has no academic graduate credentials.

RR: Yes, an M.Div is a professional degree which is intended to train people for Christian ministry, not academic work. Has Mr. Zacharias misrepresented any other credentials or achievements?

SB: Your readers may enjoy doing a quick and revealing research project to see what is troubling more and more people about Ravi Zacharias. He claims that as a new Christian in India he won something called the “Asian Youth Preacher Award.” He describes the contest in his published materials as an international event with “young people gathering from all across India and Asia.” But if folks google the award they will see that it does not exist except in Mr. Zacharias’s own writings and in articles that report his claims. The same goes for the “department of evangelism and contemporary thought” that he supposedly chaired at a place called Alliance Theological Seminary. It seems that Mr. Zacharias just made both these things up back when the Internet was not around.

Incidentally, in his memoirs, he names three judges at the Asian Youth Preacher competition. I contacted all three and they each told me it was not an international competition at all. It was India only. One of them described it as a “little contest” that he happened to be asked to judge because he was passing through. I had dinner with Mr. Zacharias last November and he told me that he would produce a letter from the competition organizer confirming the award. He has not done so. He also told me that he had a trophy from the event but that the words on it had faded.

Then, of course, there is the “Dr. Zacharias” thing.

RR: The ‘Dr. Zacharias thing’? I presume you’re referencing the use of an honorary title in a misleading manner?

SB: Yes. I should say at the outset that I consider this to be Mr. Zacharias’s least serious deception. Lots of people with honorary doctorates call themselves “Dr.” without disclosing that their degree was honorary. It is a misleading but widespread practice. What is more troubling about Ravi Zacharias, however, is that he clearly was out to deceive people into thinking that he had academic doctorates when he did not. It is not just that he routinely failed to use the word “honorary” in, say, his website bio where he listed his doctorates. He actually employed oddly ambiguous language in describing those honorary degrees. He said he was “honored by the conferring of” various doctorates. But that does not let his readers know that the doctorates were honorary. I was honored with the conferring of a Masters Degree and a Doctor of Jurisprudence. You were honored with the conferral of a PhD. But they weren’t honorary. Ohio State University tells its engineering PhD students that they better get their dissertations in on time if they want to be “honored with the conferral of a doctoral degree.” It is hard to think of a non-deceitful reason why Mr. Zacharias used such language when merely putting “hon” in would have removed all ambiguity.

To matters worse, Mr. Zacharias eventually added the word “honorary” to his website bio in late 2016 but then he removed it. The same thing happened with his official bio at the Oxford Center for Christian Apologetics, the school he founded in Oxford.

I have racked my brain to come up with some non-deceptive reason why he would actually remove the word “honorary” from his bio once it was there. [Note: Zacharias still uses the doctoral designation here.]

To make matters really worse, on December 3, 2017, his ministry issued a press release where they claimed that Mr. Zacharias is uncomfortable with people calling him “Dr.” and that he tells event organizers not to use that title in reference to him. They claimed that “confusion” has arisen due to different “cultural norms.” But this seems plainly false. The Internet record shows us that Mr. Zacharias aggressively marketed himself as a doctor since the early 1980’s. We can see it in his event announcements from those years, which are available at newspaper.com. In 2015 his official bio referred to him as “Dr. Zacharias” eight times! When I called his office around that time his personal secretary answered with “Dr. Zacharias’s office.”

For him and his ministry to now pretend that “Dr. Zacharias” was just something that he reluctantly went along with is very troubling to many of us. It suggests that his motive is not repentance but damage control.

RR: I agree with your assessment. The blurring of the line between academic and honorary degrees can happen on occasion. But it’s an altogether different matter when that blurring appears to be intentional. And I think you’ve provided good evidence of a troubling pattern which fits into Mr. Zacharias’ repeated dishonesty about his credentials.

You’ve clearly done an impressive amount of research on this topic. What has drawn you to spend so much time on this admittedly troubling case of deception?

SB: The dialogue between theists and skeptics is a hugely important one, to my mind anyway. It must be conducted without resort to false pretenses. When Ravi Zacharias comments, as he does, on things like the second law of thermodynamics, the fact that he is a professor at Oxford and studied quantum physics at Cambridge gives his arguments great credence that they would not otherwise have. Same for his arguments about complex philosophical topics like free will, morality, self-reference, and the like. Mr. Zacharias has stood before millions of people and made definitive pronouncements on these matters. His credential deceptions make it hard to tell wheat from chaff. Like trying to find a qualified dentist where people who never went to dental school are holding themselves out as “D.D.”

And, Randall, frankly, the response of the Christian corporate world to Mr. Zacharias’s credential claims has been disappointing. The attitude seems to be business as usual. As long as he brings in the bodies and sells books the publishers and pastors do business with him. Integrity has been sidelined. Take HarperCollins Christian Publishing. Their assistant general counsel assured me that he would look at the large pile of evidence I provided him showing that their own company’s Ravi Zacharias books contained wilfully false claims. A couple weeks later he told me that they had no comment. Then in April of this year, HCC announced a new book deal with Mr. Zacharias. We may now look forward to Jesus Through Eastern Eyes, due to be released in 2020.

Whither integrity?

RR: I share your dismay at the tribalism that leads Christians to overlook the moral lapses within their community, including the fabulism of an apologist like Mr. Zacharias. It hardly needs to be pointed out that if an atheist like Richard Dawkins were behaving in this manner, Christians would not hesitate to call out his dishonesty. This double standard is indefensible. Needless to say, it also does enormous damage to the credibility of the Christian witness to a skeptical world.

Thanks for taking the time to discuss these important issues with us. If a person wants to learn more about this topic, where can they go?

SB: A great deal is coming out now from Christian bloggers. One may simply google “Ravi Zacharias credentials” for a wealth of information. The Spiritual Sounding Board has done a fine job of assembling the credential deceptions in one place. You and Warren Throckmorton have also done careful work at your blogs on the credential issues. I have a book that is about to go to press and should be out by the end of the year. I hope folks will keep their eyes out for my Coverup at God, Inc.; Sex, Lies and God’s Great Apologist, Ravi Zacharias.

The post Ravi Zacharias: Apologist or Fabulist? An interview with Steve Baughman appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 14, 2018

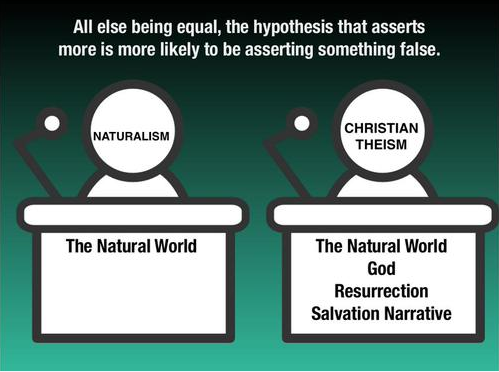

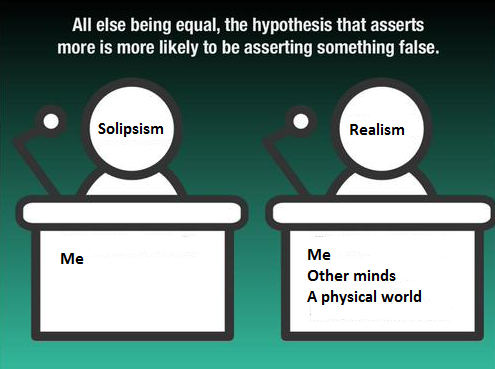

On Spurious Attempts to Favor Naturalism over Theism

In this article, I want to consider a spurious attempt to favor naturalism over theism. To be clear, I don’t take issue with the general maxim in the meme posted below. What I do dispute is the facile attempt to favor naturalism over theism based on the maxim:

In my rebuttal, I point out that if we attempt to apply that principle to favor naturalism over theism, then we ought likewise to apply it to favor solipsism over realism:

This rebuttal functions as a reductio ad absurdum. Just as it is absurd to conclude that solipsism is, ceteris paribus, to be preferred over realism, so it is absurd to suppose that naturalism is, ceteris paribus, to be preferred over theism.

Conversely, one could accept the conclusion that both solipsism and naturalism are, ceteris paribus, the preferred hypotheses. However, one could then point out that this is a weak concession because all sorts of other evidence can immediately overwhelm that preference: i.e. all else is most certainly not equal.

The post On Spurious Attempts to Favor Naturalism over Theism appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 12, 2018

A Defense of Apatheism, sort of

This autumn I will be presenting a qualified defense of apatheism at a conference. This is a draft of the paper I plan to deliver. It is in response to Jonathan Rauch’s important essay “Let it Be” in which he develops the concept of apatheism.

The link between 9/11 and the new atheism is well-established, but that terrible day also spurred another lesser known response to religious zeal. I speak of the apatheist celebrated by Jonathan Rauch in a pithy but very influential 2003 article in Atlantic Monthly simply titled “Let it Be.” Rauch begins this brief, 994-word essay in memorable fashion by recounting an occasion when he was asked to share his religious views:

“‘I used to call myself an atheist,’ I said, ‘and I still don’t believe in God, but the larger truth is that it has been years since I really cared one way or another. I’m’—that was when it hit me—‘an … apatheist!’”

And thus was born “apatheism,” a portmanteau of apathy and theism. But what, precisely, does Rauch mean by apatheism? According to what I call the standard reading of this essay, Rauch’s apatheism reflects an ignoble attitude of intellectual laziness, of mere disinterest in matters of religious significance.

While I don’t dispute the fact that some people are becoming increasingly apathetic about religious commitment, in this essay I will focus my efforts on challenging the standard reading of Rauch’s concept of apatheism. Instead, I’ll argue for what I call the charitable reading according to which apatheism reflects an admirable attempt to chasten the human tendency toward fanaticism as expressed in anti-social behavior such as zealotry, bigotry, and affrontive expressions of proselytism and disputation. When viewed from that perspective, we can see that far from representing an ignoble fall into intellectual sloth, Rauch’s particular brand of apatheism reflects an admirable attempt to constrain public conduct. And for that, it should be respected, if not celebrated.

The Standard Reading

Let’s begin with the standard reading. Several Christian apologists and theologians have interpreted Rauch’s essay as conveying a deeply troubling intellectual apathy toward metaphysical and theological questions. For example, Dinesh D’Souza argues that Rauch’s apatheists “don’t care” whether God exists and that they are, in effect, practical atheists “because their ignorance and indifference amount to a practical rejection of God’s role in the world.”

While D’Souza makes reference to apatheism only in passing, Douglas Groothuis offers a far more extensive treatment of Rauch’s essay in his book Christian Apologetics. For that reason, I will focus on Groothuis’ treatment to represent the standard reading.

Groothuis says that the apatheist of Rauch’s essay has a “relaxed attitude” toward religion, a “benign indifference” in which one refuses “to become passionate about one’s own beliefs or the beliefs of others.” Importantly, Groothuis recognizes that apatheism, like new atheism, is an intentional response to the danger of fanaticism. However, while the new atheists responded to religious fanaticism with their own secular version, Rauch’s apatheism targets all fanaticism, whether it be religious or secular. As Groothuis puts it, Rauch is seeking to provide a “tonic to incivility” that exudes the virtue of tolerance.

While Rauch’s apatheist seeks to avoid fanaticism, Groothuis insists that Rauch thereby places “tranquility above truth.” In short, Rauch’s misbegotten pursuit of civility is only secured at the cost of setting aside a swath of theological, metaphysical, and ethical questions. And this attitude, so Groothuis says, “is antithetical to the teaching of all religions and sound philosophy: that we should care about our convictions and put them into practice consistently.” In short, Groothuis charges Rauch with a toxic attitude which dissolves into a fundamentally anti-Christian intellectual sloth.

The real cost of Rauch’s misguided response to dogmatic incivility is a failure to love either God or neighbor. Groothuis makes the point by quoting Rauch’s observation that his Christian friends “betray no sign of caring that I am an unrepentantly atheistic Jewish homosexual.” As Groothuis soberly observes, “For the serious Christian, however, an attitude of apathy over the eternal destiny of another human being is not an option.”

Consequently, though apatheism may be borne out of a noble desire to avoid conflict, it sacrifices the pursuit of truth in the process and thereby becomes a textbook case of a cure that is worse than the disease.

The Charitable Reading

Now we turn to the charitable reading. This reading begins with the point that Groothuis himself makes: namely, that Rauch proposes apatheism as a way to avoid the dangers of fanaticism. It is also important to underscore the point that Rauch’s target is not religious fanaticism, per se. Rather, he targets fervent fanaticism generally, and it can be exemplified in atheistic or secular attitudes as surely as religious ones. As Rauch writes:

the hot-blooded atheist cares as much about religion as does the evangelical Christian, but in the opposite direction. “Secularism” can refer to a simple absence of devoutness, but it more accurately refers to an ACLU-style disapproval of any profession of religion in public life—a disapproval that seems puritanical and quaint to apatheists.

Thus, Rauch has as little sympathy for the “hot-blooded atheist” as for the fire and brimstone street preacher. Both of these folk need to take an apatheistic chill pill.

At this point, it may help to illustrate the kind of behavior that Rauch is seeking to avoid. And to that end, I’ll briefly summarize two examples of fanaticism or dogmatic incivility, one religious, and the other secular.

We can begin with the religious example. When I was a teenager I was taught that we had to do street evangelism by going out and accosting people with this question: Do you know where you would go if you died tonight? I still remember two young women shaking off our religious invitation with a forceful riposte: “Leave us alone!” My companion, undeterred, followed them down the street calling out with increasing fervency, “But you have to believe!” As for me, I channeled my evangelistic fervor in another direction, by emptying a newspaper box holding copies of the Jehovah’s Witness magazine Awake! and tossing them in a dumpster. If we couldn’t win souls, at least we could prevent the JWs from damning them!

That’s an example of the kind of behavior that Rauch would like us all to avoid, but as noted above, it is not limited to religious people. Just consider Barbara Ehrenreich’s description of growing up in a fervent secular household:

I was raised in a real strong Secular Humanist family—the kind of folks who’d ground you for a week just for thinking of dating a Unitarian, or worse. Not that they were hard-liners, though. We had over 70 Bibles lying around the house where anyone could browse through them—Gideons my dad had removed from the motel rooms he’d stayed in. And I remember how he gloried in every Gideon he lifted, thinking of all the traveling salesmen whose minds he’d probably saved from dry rot. Looking back, I guess you could say I never really had a choice, what with my parents always preaching, “Think for yourself! Think for yourself!”

Whether the issue is a Christian wannabe evangelist preaching repentance and destroying JW literature or a secular evangelist preaching freethought and stealing Gideon’s Bibles, the same fanaticism is on display.

We can identify the following disturbing traits in these cases. First, both teen Randal and Mr. Ehrenreich exhibited zealotry, the expression of excessive zeal in their beliefs. Second, this zeal expressed itself in bigotry, an intolerance toward the beliefs of others, particularly evident in the effort to censor alternative views (Awake! Magazine, the Gideon’s Bibles). And finally, both exhibited an affrontive style of proselytism and disputation whether it was teen Randal accosting people in the street with the threat of hell or Mr. Ehrenreich always preaching “Think for yourself!” (One can only imagine the fireworks if young Barbara had actually dared to think for herself by embracing religion.)

It’s also worth keeping in mind that the target of such fanatical behavior is not limited to members of an outgroup, for it can equally target in-group members. Indeed, sometimes the pursuit of group purity encourages an even more rigorous enforcement of group solidarity. Witness the irenic Philip Melanchthon who, late in life, sadly commented that he welcomed his impending death so that he might “escape ‘the rage of the theologians.’”

Like Rauch, I applaud the move away from this kind of in-your-face fanaticism, whether it be religious or secular. And this brings me to the second point: Rauch’s apatheism is not simply a matter of becoming lazy about religious belief. Rather, it represents a determined commitment to chasten our own innate impulses toward fanatical zealotry, bigotry, and affrontive proselytism or disputation.

We’ve all heard the maxim “Never discuss politics or religion in polite company” and we all know why. Religion and politics are topics which are uniquely able to inflame passion and stoke division. And because human beings have a tendency toward conflict in these areas, this is precisely why Rauch proposes we determine to guard ourselves against a lapse into overly zealous, potentially intolerant, and excessively aggressive behavior. Rauch puts the point like this: “it is the product of a determined cultural effort to discipline the religious mindset, and often of an equally determined personal effort to master the spiritual passions. It is not a lapse. It is an achievement.” This is a crucial point: Rauch’s apatheism, this chastening of our radical tendencies, is not mere laziness or sloth: rather, it is an earnest discipline.

Consider an example from that other incendiary field: politics. A married couple, Steve and Darlene, are traveling to the house of Steve’s parents for Thanksgiving just after the 2016 presidential election. While both Steve and Darlene campaigned for Hillary Clinton, Steve’s dad voted for Trump. As they drive, Darlene coaches Steve not to get into an argument with his dad about the president-elect: “Don’t take the bait, Steve. I don’t care if your dad wears his MAGA hat all through dinner. I forbid you to talk politics. You need to control yourself!”

The same advice that Darlene gives to Steve to avoid an incendiary topic and with it the risk of lapsing into fanatical behavior could likewise be given to the religious devotee with similar inclinations. Insofar as you have a tendency toward dogmatic zeal, bigotry, or affrontive proselytism or disputation, you should simply avoid these topics. This is not laziness. It is, rather, a careful discipline.

Finally, let’s turn to consider what Rauch says about Christians who are apatheists. This is a particularly important point because while some of Rauch’s statements here might appear especially damning, when read with the appropriate nuance I propose that they actually reveal admirable exercises of wisdom fully congruent with love of God and neighbor.

Here’s how Rauch describes apatheistic Christians: “Most of these people believe in God …; they just don’t care much about him.” This lack of care apparently extends to one’s neighbor as well. Rauch continues:

I have Christian friends who organize their lives around an intense and personal relationship with God, but who betray no sign of caring that I am an unrepentantly atheistic Jewish homosexual. They are exponents, at least, of the second, more important part of apatheism: the part that doesn’t mind what other people think about God.

Even if what I’ve said thus far about Rauch’s apatheism is true – that is, even if it largely consists of an admirable determination to constrain the tendency toward fanaticism on incendiary topics – surely at least this attitude is problematic, is it not? After all, a Christian is called to love God with all their heart, soul, mind, and strength, and to love their neighbor as themselves. But Rauch appears to describe quite the opposite attitude with Christians who don’t particularly care about God or other people.

However, it seems to me that a closer reading of Rauch can defend him against this charge. While Rauch says that apatheistic Christians “just don’t care much” about God, he immediately adds that he knows many apatheistic Christians who “organize their lives around an intense and personal relationship with God”. This presents us with a puzzle: how can it be that they don’t care about God if they organize their lives around an intense and personal relationship with him?

The answer, I would suggest, is that Rauch is using “care” in a very particular way with respect to public expressions of religious fanaticism. In other words, “care” is understood here to consist of visible displays of devotion and piety. But it should be clear to any Christian that such visible actions do not thereby constitute a truly devotional life; indeed, they may even run counter to it. For example, when Jesus instructs on the discipline on prayer he advises his listeners to pursue private devotion rather than grandiose, public displays (Mt 6:5-6). Thus, so-called publicly visible care has little to do with one’s fulsome love of God.

Fair enough, but what about the fact that Rauch says his own Christian friends “betray no sign of caring” that he is “an unrepentantly atheistic Jewish homosexual”? Once again, we need to keep in mind Rauch’s very particular understanding of “caring.” These Christians may not “care” in the sense of engaging in public and visible displays whereby they confront and condemn Rauch’s beliefs and actions. But that hardly entails that they do not truly care about their non-Christian brother. Indeed, for all we (or Rauch) know, they may pray for him for hours a day.

Further, keep in mind that Rauch knows these individuals have deeply devout Christian faith. Their religion is no secret to him. Furthermore, it would presumably be commonly understood between parties that if Rauch had any questions about their faith, he’d be more than welcome to ask. We can assume that the door is open for further conversation, should he be interested. With that in mind, this essay gives no hint at present that Rauch is interested. So it should not surprise us that his friends have opted not to broach the subject at this time. Rather, they are simply sharing life together with their non-Christian friend while being sure not to repel him with off-putting displays of zeal, bigotry, or affrontive proselytism or disputation.

To be sure, you may not agree with the behavior of these apatheistic Christians or with the reasoning I’ve imputed to them. You may instead prefer the Christian to adopt a more confrontational expression of care toward the non-Christian. Even so, it still seems to me that the behavior Rauch describes is fully consistent with love of God and neighbor.

Conclusion

In this paper, I’ve sought to argue that the standard reading of Rauch’s apatheism is incorrect. Far from advocating for an ignoble intellectual sloth, Rauch instead makes an important point about chastening our own tendency toward radicalism. Within that context, he also offers a more balanced conception of devotional commitment to God and neighbor, one which is centered on the interior life rather than external, visible displays of piety and devotion.

Having said all that, I do want to extend an important olive branch to the standard reading. While I admire Rauch’s proposed discipline of chastening fanatical impulses, it does seem to me that his own present disposition is not a matter of exercising a discipline but rather of simply not caring. Indeed, that’s precisely what he says: “it has been years since I really cared one way or another.”

In short, it appears to me that “Let it Be” begins with one definition of apatheism – the state of not caring about the truth of religious or metaphysical questions – before Rauch then segues to a second definition of apatheism, one which describes the discipline of chastening fanatical impulses.

Thus, it would appear that the standard reading gets Rauch’s own disposition correct. Where it goes awry is in failing to recognize that Rauch conflates his own disinterest in religious and metaphysical questions with the principled chastening of fanatical impulses that he focuses on for the bulk of the essay. Given that these are, in fact, very different topics, we should ask how we might best disambiguate this unfortunate conflation. In response, I propose that we continue to use the term “apatheism” to refer to the sense described by the standard reading and exemplified by Rauch’s own religious disinterest. Meanwhile, we could refer to the latter concept of self-control with the Greek term enkrateia, a word that philosophers like Plato used to refer to an internal wisdom and self-control over the exercise of one’s passions. But one thing is clear: it is deeply misleading to refer to the latter attitude as apatheism.

Rauch, “Let it Be,” The Atlantic (May 2003), https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/...

Rauch, “Let it Be.”

What’s So Great About Christianity p. 24. While D’Souza doesn’t reference Rauch here, he does refer to him on page 36.

Groothuis, Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith (Downer’s Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2011), 150.

See Randal Rauser, You’re not as Crazy as I Think: Dialogue in a World of Loud Voices and Hardened Opinions (Colorado Springs, CO: Biblica, 2011), 63-70.

Groothuis, Christian Apologetics, 151.

Groothuis, Christian Apologetics, 150-52.

Groothuis, Christian Apologetics, 151.

Rauch, “Let it Be.”

For all the gory details, see What’s So Confusing About Grace? (Canada: Two Cup Press, 2017), chapter 7.

Barbara Ehrenreich, “Give Me That New-Time Religion,” Mother Jones (June/July 1987), 60.

Williston Walker with Richard A. Norris, David W. Lotz, and Robert T. Handy, A History of the Christian Church, 4th ed. (New York: Scribner, 1918, 1985), 528.

Rauch, “Let it Be.”

Rauch, “Let it Be.”

Rauch, “Let it Be.”

The post A Defense of Apatheism, sort of appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 11, 2018

How to tell your article hit the mark

In this case, the article is “Top 5 Problems With Contemporary Christian Apologetics” at The Christian Post (CP).

And the way you can tell it hit its mark is because it made the right people happy and the right people angry.

The first is illustrated in the very first comment posted in response to the article at CP:

“An outstanding analysis of the issue here. Praise God, and bravo to the author for this very thoughtful, honest and illuminating piece!”

Well, thank you. Thank you very much.

The second is illustrated by the next three comments posted at CP. I won’t bore you by reproducing all three paragraph-length comments of invective. But here are a couple choice excerpts:

“We should pray for men such as this. For all the lost of course… but especially for men such as this author… who are leading believers astray. Who with out the mercies of God will find an especially dark punishment reserved for them for their deception.”

“My hope and prayer for the readers of this website is that they see through the lies that this author continues to spew through his posts on this site. His attack on “fundamentalism” is nothing more than a direct attack of God’s word. I am offended and enraged by this. What is written above and in his other posts are a direct attack of God’s word, the proper interpretation of it, His truth and Holiness (inerrancy), and His complete and closed revelation to man in the canon of Scripture. What is being labeled as “fundamentalism” is in fact nothing more than genuine faith in absolute truth.”

Just to be clear, I don’t set out to “offend” and “enrage” fundamentalists. But the fact that I did offend and enrage this fundamentalist suggests that my analysis hit the mark.

So keep that in mind the next time you write an article. Don’t expect everybody to love what you have to say. All you need to focus on is making the right people happy and the right people angry.

The post How to tell your article hit the mark appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 9, 2018

Help me kick cancer in the teeth with my steel-toe running shoes

Every autumn, I join tens of thousands of people in an annual run to make breast cancer history. I run for my mom, a cancer survivor, and for the millions of other people who have faced this terrible disease. Every year, I spend hundreds of dollars and hundreds of hours to keep this website and blog running. If you’ve benefited from my work, I hope you’ll consider making a donation to my fundraiser to kick cancer in the teeth once and for all. You can donate here.

The post Help me kick cancer in the teeth with my steel-toe running shoes appeared first on Randal Rauser.