Randal Rauser's Blog, page 88

December 18, 2018

The Lying Apologist: A Review of Cover-Up in the Kingdom

“Whoever can be trusted with very little can also be trusted with much, and whoever is dishonest with very little will also be dishonest with much.” -Luke 16:10-

“Whoever can be trusted with very little can also be trusted with much, and whoever is dishonest with very little will also be dishonest with much.” -Luke 16:10-

For many Christians, Ravi Zacharias is revered as perhaps the church’s leading apologist, a man with a string of bestselling books, a well-respected international ministry, and more than forty years of dynamic preaching and teaching.

And yet, if Steve Baughman is correct, Zacharias is also a habitual liar and fabulist, and perhaps even a bully and a predator. Cover-Up in the Kingdom presents Baughman’s case. And the word “case” is well chosen: Baughman is a lawyer by training and the book presents itself as something of a legal brief replete with multiple appendices, including tweets, legal documents, and emails from Zacharias himself. All of this provides a cumulative evidential argument for entrenched patterns of deception.

In the book, Baughman provides two primary lines of evidence against Zacharias. In this review, I’ll briefly summarize each charge before raising some criticisms of the book and then drawing my final verdict.

Zacharias as Chronic Fabulist

I’ve decided to call the first charge chronic fabulism, as Baughman provides a litany of evidence that Zacharias has embellished and fabricated his credentials, achievements, and personal experiences, and that he has done so for decades.

Baughman begins in the 1960s when a young Zacharias won a regional preaching contest in India which he later described as the prestigious “Asian Youth Preacher Award.” By the 1970s, Zacharias was regularly billing himself as a South Asian Billy Graham. (Some period advertisements are reproduced in the book.) Already at this point, the tendency toward self-promotion is evident.

A few years later, while teaching at Alliance Theological Seminary in the early 1980s, Zacharias took to describing himself as the chairman for the “Department of Evangelism and Contemporary Thought,” despite the fact that no such department existed at the seminary.

Around that same time, Zacharias received his first honorary doctorate. Despite the fact that his highest earned academic degree was (and is) an MDiv, from that point on, he regularly promoted himself as “Doctor” Zacharias. At the same time, he carefully avoided the use of the standard “Hon.” designation which would’ve identified his PhD as an honorific title rather than an earned degree. Zacharias and RZIM have continued this practice down to the present day: “Although at times Ravi disclosed that his doctorates were honorary, for the most part, he assiduously avoided using the word ‘honorary’ in his bio and publicity materials.” (32)

Over time, Zacharias’ fabulism appears to have grown more brazen. For example, on multiple occasions, he has claimed that he studied quantum physics with Professor John Polkinghorne at Cambridge. This is an extraordinary claim, especially since, as noted above, Zacharias’ highest earned degree is an MDiv. (What kind of autodidactic genius is it that can jump from a professional degree in Christian ministry to high-level research in quantum physics?!)

After investigating this suspicious claim, Baughman concludes that, at most, Zacharias audited a course on theology and science with Polkinghorne in 1990. The seamless move from auditing a course on science and religion to studying quantum physics encapsulates Zacharias’ habitual tendency toward fabulism and lying.

Baughman provides many other examples of Zacharias’ fabulism and lies including his recent outrageous claim that he is, of all things, a professor at Oxford University.

All this and more is carefully documented in Cover-Up in the Kingdom and together it provides a powerful cumulative case that Zacharias is a chronic fabulist who habitually embellishes and outright fabricates his credentials, achievements, and personal experiences. To my mind, this evidence alone is enough to put the kibosh on this man’s “apologetic ministry”.

However, it gets worse.

Zacharias as Bully … and Predator

Baughman’s second line of evidence focuses on Zacharias’ illicit relationship with a young married woman named Lori Anne Thompson. The relationship carried on for a period of two years (2014-16). While there is no evidence that Zacharias and Thompson were physically intimate, they did exchange a series of emails, images, and texts of a sexual nature, including Thompson providing Zacharias with sexually explicit photos at his request.

After two years, Thompson determined to break off the relationship and tell her husband. When she informed Zacharias of her decision, he threatened to commit suicide in an email which is reproduced within the book. (Nor is this Zacharias’ first brush with suicide; in his memoirs, Zacharias recalls attempting suicide as a teenager after which one of their house servants saved his life. Baughman drily observes, “This man saved Ravi’s life. This man’s name was house servant.” (18))

A month later, the Thompsons hired a lawyer who subsequently demanded a substantial cash settlement as a condition for the Thompsons to maintain their silence. Zacharias responded by suing the Thompsons and in the ensuing public relations battle, Zacharias and his legal team effectively presented the Thompsons as grifters who were attempting to blackmail him in a shady scheme.

There are multiple problems with Zacharias’ attempt to present himself as a victim in this sordid affair. To begin with, it was Zacharias who gave Thompson the number to his private Blackberry so they could communicate privately with encrypted technology. Now Zacharias wants us to believe that Thompson was harassing him for two years, sending him naked photos against his will. If he really was being harassed in this manner, then why didn’t he change his phone number? Why didn’t he call the police and get a restraining order? Why didn’t he inform his ministry (RZIM) and supporting denomination (the C&MA)? Why, instead, did he remain silent and continue communicating with Thompson for two years? And why did he threaten to kill himself when she said she was going to her husband?

Zacharias’s supporters have suggested that the Thompsons had a history of financial problems and suing churches. As Baughman demonstrates, these charges are spurious and thus look like a mere attempt to smear Zacharias’ accusers: “Ravi allowed his lawyers to wage a demonstrably false and vicious public relations assault on the Thompsons, all to preserve the image he had cultivated since his youthful conversion to Christ.” (69)

Baughman also addresses questions about Lori Anne in particular and provides several lines of evidence that she was a genuine victim of Zacharias’ predatorial and bullying behavior. All in all, it is a devastating portrait supported by several documents including emails and legal filings which collectively illustrate Baughman’s skill as a litigator. And it fits with the portrait of Zacharias in the earlier chapters as a self-aggrandizing fabulist.

Moral Indignation vs. Rhetorical Indulgence

Baughman notes that Zacharias’ defenders have tended to dismiss his allegations, chalking them up to Baughman’s own hatred of God (4). While this is unfortunate, it is hardly surprising given the tribalistic nature of many Christians. But it does suggest that Baughman’s best chance to reach Christians is found in adopting a measured tone sans any unnecessarily alienating rhetoric.

For this reason, it is unfortunate that Baughman occasionally descends from his typical posture of righteous indignation into taking cheap rhetorical shots. For example, consider this withering criticism of Zacharias’ decision to move to Canada:

“For some reason God wanted the newly regenerate Ravi Zacharias to leave India for Canada. That is to say, God wanted Ravi as far away as earthly possible from the truly destitute people dying every day in the streets of Delhi with no loving hand to guide them to salvation.” (22)

While Zacharias may indeed be a narcissist who cares little for the poor, it seems tendentious to interpret this decision to move to a developed country in such an uncharitable manner.

At another point, Baughman expresses his frustration at the Christian publishers who have dismissed concerns about Zacharias’ credibility as follows: “In the eyes and interests of HarperCollins Christian Publishing, Ravi Zacharias is the beautiful whore, or at least the useful holy man, who must, at all cost, be kept at work.” (13)

Beautiful whore? Ouch.

Needless to say, this kind of rhetorical indulgence will alienate some readers unnecessarily and provide the resistant reader with an excuse to set aside the whole argument. That would be unfortunate because this is an important book.

Why You Should Read This Book

Over the last few weeks, several Christians have asked me why I want to review Cover-Up in the Kingdom. The question seems to be based on that same tribalism that I referenced above. In other words, don’t criticize our guys.

Sorry to be the bearer of bad news, but a habitual liar and fabulist is not my guy. And it doesn’t stop with Zacharias. Perhaps the most disturbing lesson of Cover-Up in the Kingdom is that Zacharias has been enabled by the silence and complicity of many other Christians including apologists like John Lennox and Os Guinness, megachurch pastor Mac Brunson, professor Jeremy Begbie, and countless functionaries at institutions like RZIM and the C&MA denomination.

I like to say that in Christian apologetics, good arguments are important but a winsome presentation is even more important. I’d now like to add that one’s moral integrity is most important of all. And moral integrity requires Christians to speak out and denounce Ravi Zacharias and his enablers. If we claim to follow He who is the Truth (John 14:6), how could we do anything less?

You can purchase your copy of Cover-Up in the Kingdom for a mere $5 on Kindle here.

The post The Lying Apologist: A Review of Cover-Up in the Kingdom appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 17, 2018

The Solution to Christians Becoming Atheists (Part 2)

This is the third and final installment in my interview/conversation with Dr. John Marriott on the issue of Christians leaving the faith to become atheists. Here are links to the first installment, “The Problem of Christians Becoming Atheists,” and the second installment, “The Solution to Christians Becoming Atheists (Part 1).” Needless to say, I strongly recommend reading the first two installments before this one.

This is the third and final installment in my interview/conversation with Dr. John Marriott on the issue of Christians leaving the faith to become atheists. Here are links to the first installment, “The Problem of Christians Becoming Atheists,” and the second installment, “The Solution to Christians Becoming Atheists (Part 1).” Needless to say, I strongly recommend reading the first two installments before this one.

JM: Well, let’s get to the third suggestion. Earlier, I mentioned that a problem for deconverts was trying to maintain belief in the biblical narrative while living in the 21st century. I think it is important to flesh this out a bit.

Former believers sometimes explain it as analogous to an adult trying to believe in Santa Claus. It’s easy for kids to believe in Santa because their understanding of the world is so primitive and ignorant that the Santa story can fit within it without much difficulty. But as they get older and their understanding of the world grows it squeezes out any room for Santa. Somewhere between 6 – 10 years of age, the idea of an overweight man sliding down all the chimneys of the world in one night, with a sack of presents begins to feel suspect. Over time that suspicion will grow as they learn more about the nature of reality. During this process a growing sense of cognitive dissonance sets in. They have become aware that much of the Santa story doesn’t add up, but they may still want to believe in Santa, so they seek answers to their own internal skepticism that will let them maintain their belief in Santa and still be rational. Eventually, however, all children come to the point where they can’t believe in Santa anymore. The cognitive dissonance produced as a result of what they have come to know of reality and their belief in Santa Claus reaches a point where it can only be resolved by admitting what they know to be true; Santa does not exist.

Something similar underwrites a significant percentage of deconversions. The biblical narrative that once easily fit within their childlike understanding of reality began to get squeezed out as they matured in their understanding of reality. The stories in the Bible about miracles, witches, giants, demons, etc. began to feel as out of place as Santa. To resolve the problems they may seek answers that will allow them to continue to believe in such things as adults in the 21st century. This is the experience not just of those who deconvert but all educated, reflective Christians today. I suspect that even for those that do remain Christians, the cognitive dissonance never completely goes away, it just has been reduced to a level that allows them to continue to believe. For deconverts however, the cognitive dissonance is not sufficiently assuaged by apologetics. It grows despite their efforts and reaches a tipping point. As in the case with Santa, the only way to resolve the tension is to admit what they know is true. God does not exist.

RR: Ouch. Sounds pretty bleak. So what’s the way forward?

JM: Responding to this challenge is difficult because it is closely connected to the power that culture has to shape our thinking. And we have very little ability to change that. But let me offer three brief suggestions.

First, we need to do a better job of doing apologetics. I appreciate you and your work because it is measured, articulate and you know what you are talking about. So much internet apologetics and even published works at the popular level are unhelpful. Amateurs who don’t know what they are talking about parrot the arguments of qualified philosophers, historians and scientists, without having the depth of understanding needed to do it well. Individuals who leave the faith should be leaving because they found the best of Christian thinking to be lacking, not because a self-styled apologist let them down. Much more could be said here.

RR: That’s why I stopped referring to the Borde, Guth, and Vilenkin Theorem in debates on cosmology and God’s existence: I didn’t really know what I was talking about! I think we should all be more careful about attempting to amass a bag of talking points or factoids to support our view when we don’t really understand the conceptual frameworks in which they’re embedded.

JM: Second, we need to help folks see the role of plausibility structures, social imaginaries and other socio-cultural factors in influencing our thinking. What we take to be rational, and what answers we are willing to consider are already determined in part by when and where we live. As Charles Taylor has so persuasively argued, the conditions of belief have changed and they make it harder to believe in the biblical story. We live in an increasingly secular culture. But what needs to be pointed out is this is not because the “secular” was inevitable as humanity evolved. Nor is it a sign that we are becoming more rational in some objective sense. The secular turn is as much a construct, and product of historical factors as the religious nature of the Middle Ages was. The secular culture and its attendant “rationality” is not what is left over after you subtract religion and superstition. It is a construal with a philosophic lineage. As such, we should remind Christians that beliefs in the miraculous, and strange, which feel rationally out of place within our cultural moment, do so, not because they are inherently irrational but because we are secular. To counter the negative affective influence of our secular age on faith formation, we need to immerse ourselves in another culture; the church.

RR: Yeah, that’s a great point. I’m reminded here of the following quote from new atheist Sam Harris in which he describes atheism simply in terms of rational belief:

“Atheism is not a philosophy; it is not even a view of the world; it is simply an admission of the obvious. In fact, ‘atheism’ is a term that should not even exist. No one ever needs to identify himself as a ‘non-astrologer’ or a ‘non-alchemist.’ We do not have words for people who doubt that Elvis is still alive or that aliens have traversed the galaxy only to molest ranchers and their cattle. Atheism is nothing more than the noises reasonable people make in the presence of unjustified religious beliefs.”

Harris seems to have no awareness that he has a worldview no less than the “religious” people he disparages. Time and again, I find average atheists expressing a similar view to Harris: they think they simply have a neutral, rational view of reality rather than recognizing that they have a historically conditioned finite perspective no less than anybody else.

JM: The third counter measure we can apply in helping believers maintain faith in the midst of a secular culture that makes them feel akin to an adult believing in Santa, is to find good communities of faith that reaffirm the biblical narrative we indwell. Authoritative communities like local churches (and to a degree the global church) act as plausibility structures, the necessary social framework for belief maintenance. Space prevents me from saying too much here about plausibility structures and the crucial role they play in faith formation. But I would encourage readers to pick up Peter Berger’s The Sacred Canopy. In it Berger demonstrates the role and importance of the church, specifically church communities, in providing legitimacy to the biblical narrative. This was true not only in the Middle Ages, but also in our own. Being around healthy, biblical communities that reinforce the truth of Christ through preaching his word, worshipping him and loving each other well, can powerfully counter the faith draining effect our secular age can have on faith formation and maintenance.

RR: I certainly agree. Indeed, some years ago I wrote an article about this very idea titled “Worshipping a Flying Teapot? What to do when Christianity looks ridiculous.” In addition, the following quote from Os Guinness seems particularly relevant here:

“Roman Catholicism is more likely to seem true in Eire than in Egypt, just as Mormonism is in Salt Lake City than in Singapore, and Marxism in Moscow than in Mecca. In each case, plausibility comes from a world of shared support.”

So yeah, I agree heartily with your point about the critical importance of communities of shared belief.

But as we conclude, let me push back a bit on a couple of points. First, what would you say to the person who worries that your analysis that there is no privileged perspective — like the modern secular view — leads to relativism? That is, we just have a multiplicity of independent and equally true perspectives?

JM: I would say that just because we cannot extricate ourselves from our perspective – embedded as it is in a particular time and place – that does not entail relativism. At least ontologically, anyway. We may see things from a perspective, but that doesn’t mean reality itself is a social construct with nothing beyond it. Beliefs are either true or false depending on how they reflect reality, not if my peers let me get away with holding them. The challenge is how to demonstrate which view best reflects reality. To do that I would appeal to some non-foundationalist forms of persuasion and analysis. Examples here would include, the work of Alasdair MacIntyre, Lesslie Newbigin, and Esther Meek, among others.

RR: Okay, now for my second question. What would you say to the person who worries that your emphasis on securing belief within mutually reinforcing belief communities could encourage indoctrination? For example, if the Flat Earth Society realizes that the next generation will only accept a flat earth if they continue to live in a community of likeminded flat earthers, then they may never be exposed to rational critical thinking and evidence to question their entire framework.

Do you see that as a danger?

JM: Theoretically I suppose it is. But what I have in mind isn’t a siege or ghetto mentality. Rather, I am advocating that believers take advantage of the great resources that God has given them in the church. One of which is that it provides the encouragement they need as “strangers and aliens” in the broader culture. Good churches, or outposts of the Kingdom, will be those that seek not to indoctrinate but to be channels through which the Spirit of God can work in bringing about spiritual formation. One way they can do so is by helping individuals to love God with their minds. Loving God with one’s mind entails evaluating all things and holding fast to what is true. The church has nothing to fear from critical thinking. In fact, it should be known for doing so with excellence.

There is much more that could be said on the subject of deconversion. If readers would like to learn more one way they can do so is to visit my website www.johnmarriott.org . There you will find the latest research, help for those trying to understand the loss of faith, and hope for those trying to maintain it. A second option is to pick up a copy of my recent book, A Recipe For Disaster: Four Ways Parents and Churches Prepare Individuals to Lose Their Faith and How to Instill a Faith that Endures. In it you will find more data on the rates and scope of deconversion, a survey on what the New Testament says about apostasy, and more about how well meaning Christian parents and church leaders unwittingly contribute to the process of deconversion.

Thanks Randal for taking the time to chat with me. It’s been a pleasure.

The post The Solution to Christians Becoming Atheists (Part 2) appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 13, 2018

The Solution to Christians Becoming Atheists (Part 1)

In this article, I continue a conversation with John Marriott on Christianity and atheism based on his new book, A Recipe for Disaster. In part one, Dr. Marriott summarized some of the catalysts that lead to Christians becoming atheists. In this article, we continue the conversation by turning to consider ways that Christians might seek to address this trend.

In this article, I continue a conversation with John Marriott on Christianity and atheism based on his new book, A Recipe for Disaster. In part one, Dr. Marriott summarized some of the catalysts that lead to Christians becoming atheists. In this article, we continue the conversation by turning to consider ways that Christians might seek to address this trend.

RR: John, in the first part of our exchange you laid out some sober statistics on the numbers of Christians becoming atheists. You also provided an astute overview of the main problems that contribute to this trend. All in all, it was a rather disheartening, if necessary, introduction to the problem.

At this point, I am reminded of the seventeenth century Quaker, Thomas Ellwood. After he read the great Puritan poet John Milton’s magisterial work, Paradise Lost, Ellwood remarked, “Thou hast said much here of Paradise lost, but what hast thou to say of Paradise found?” In the spirit of Ellwood, I can say that you’ve done much to diagnose the problem of Christians becoming atheists. Now, what can you propose by way of a solution?

JM: Admittedly, it’s much easier to diagnose problems than it is to solve them. But I think there are some things that we can do to avoid setting believers up for a crisis of faith. You may have noticed that the three factors I identified all relate to how the church / parents socialize deconverts. In pointing these out, I don’t mean to imply that the church is the cause of deconversion. Deconversion is complex and ultimately inscrutable. But for many former Christians their religious socialization played a crucial role. Of course, some of the factors that produce a loss of faith are completely out of the control of parents and churches.

Consider two examples. First, individuals who possess certain personality traits and highly rate specific values are statistically more likely to lose their faith than the average believer. Likewise, our increasingly pluralistic / secular culture can have a withering effect on keeping the faith. Parents and churches have no control over either of those. But they do have direct control over how they pass on the faith. So we need to get it right. Therefore, in response to the three problems of faith transmission I raised earlier, I offer three responses that I believe not only avoid setting up believers for a crisis of faith but give them the best chance for a faith that endures.

RR: Well said. To illustrate your first point, some research suggests that autism is positively correlated with a tendency toward atheism. More generally, we’ve probably all met people for whom belief and commitment came naturally and others for whom it has always been a struggle.

And as for the second point, there is no doubt that a post-Christian culture brings unique challenges. Though, I would add that Soren Kierkegaard famously pointed out how avowedly “Christian” cultures can be subversive of genuine faith as well.

Anyway, how about we look at a quick overview of your three responses?

JM: If my first critique involved requiring believers to affirm an excessive and bloated set of non-negotiable beliefs in order to be a Christian, what is the alternative? I suggest that we identify those beliefs that are minimally sufficient to adopt in order to be considered a Christian and then emphasize those, leaving all others open for discussion. I think there are two sets of beliefs that meet that requirement: The salvation message and the ecumenical creeds of the church. The first is sufficient for salvation, the second for orthodox belief.

Salvation, as far as correct belief is concerned, has to do with possessing a fond appreciation that the work of Christ on the cross and his subsequent resurrection are the means by which an individual has their sins forgiven and are reconciled to God. Fond appreciation, in this sense, includes both believing what the Bible claims about Christ’s substitutionary death and trusting him as the savior.

There is more to being a Christian, however, than just being saved. There is also the matter of what the Christian community has identified as the boundary markers for correct belief. Soteriologically speaking, an individual may be a Christian, that is they are saved, but in the broader theological sense they may not be very Christian at all. A person can be born-again and hold to all kinds of aberrant and unorthodox theology. To guard against this the early church crafted statements that identified specific beliefs that were important for Christians to hold in order to be orthodox in their faith.

These are commonly known as the ecumenical creeds of the church, the Apostles’ Creed 200 CE, the Nicene Creed 381 CE, and the Chalcedonian Creed 451 CE. These three creeds, accepted by all three major branches of the church, identify the minimal set of beliefs that a person ought to affirm in order to be orthodox in belief. It is these major theological doctrines that we should be concerned to pass on. Not the unique and sometimes picayune convictions we hold individually or as a church.

By emphasizing these minimal tenets of the faith, we do two things. First we make it less likely that we will pass on a distorted version of Christianity by equating our denominational distinctives and personal opinions of what it means to be a Christian with Christianity itself. Second we give believers a faith that is both sturdy and flexible. Sturdy in that it is built upon major doctrines accepted and defended by believers throughout history; flexible because the creeds do not commit one to any particular theological model for making sense of their content.

To sum up my first suggestion on how to avoid setting up believers for a crisis of faith, I suggest we should place no greater doxastic burden on individuals than that which is sufficient for salvation and mere orthodoxy. In all other areas of belief there should be freedom to reject beliefs without fear that in doing so one is rejecting Christianity.

RR: Growing up in a dispensational Pentecostal church, we had a long list of required beliefs ranging from young earth creationism to pre-tribulation premillennial dispensationalism. (Whew, that’s a mouthful!) Heck, there was a time when I was even suspicious of post-tribulation dispensationalists. Needless to say, I didn’t even have categories for non-dispensationalist Christians. They might as well have been from Mars!

These days, one finds all sorts of other things being added to mere Christianity. For example, are you pro-choice or pro-life? Pro-gay marriage or anti-gay marriage? Calvinist or Arminian? Penal substitution atonement or Christus Victor? Complementarian or egalitarian? Pacifist or just war theorist? Capitalist or socialist? All important topics, to be sure, but none of them is at the core of Christian identity. And I think we’d all do well to keep the main thing the main thing.

JM: My second suggestion is that we need to do a better job of articulating important theological concepts, especially when it comes to God. I have no doubt that a number of former believers have a balanced and theologically robust conception of God. No doubt some would say that a biblical conception of God is precisely what brought them to the place where they could not believe in him anymore. As tragic as I think that is, at least they are rejecting the God of the Bible, not the God of their ill-formed theology. As I mentioned previously, many deconverts reveal in their deconversion stories that the catalyst for leaving the faith came as a result of being disappointed with God, or at least the concept they had of him.

In reality though, they had a significantly unbiblical conception of God, one that more closely resembled the God of Moralistic, Therapeutic, Deism identified by sociologist Christian Smith, than the God of the Bible. MTD holds that God exists (deism), he wants us to be happy (therapeutic), and we should treat others in ways that maximizes their happiness by being good, nice, and fair to each other (moral). If that is how we make others happy, it is reasonable to conclude that is how God makes us happy, by being good, nice, and fair. According to Smith, for American teenagers “God is something like a combination Divine Butler and Cosmic Therapist: he is always on call, takes care of any problems that arise, [and] professionally helps his people feel better about themselves.” But biblically speaking, this is not what God is like, nor how he acts. The conception is not mapping onto reality.

When one’s conception of God does not adequately map onto the reality of who God is, it can cause a crisis of faith. But it doesn’t have to. We can largely avoid these kinds of faith shaking disappointments by providing believers with a more biblical conception of God and what to expect as one of his followers. Without question there is great reward to be expected from following Jesus, both in this life and the next. But the rewards, which are primarily spiritual and relational, are experienced amidst a fallen world. Over and over again, the Bible tells us through stories and direct statements that this is a broken world, controlled in significant measure by a malevolent being. That suffering is par for the course. That followers of Jesus often will suffer both moral and natural evil. That God himself will allow bad things to occur, or even have a hand in bringing them to pass for reasons that may be opaque to us, but are for an ultimate good.

RR: Yes, if people think that this life is simply about being as happy as one can be, they are bound to be disappointed. From a Christian perspective, the primary focus of this life is about becoming holy not merely happy.

JM: There is no better example of this than Jesus himself. He was (for the most part) homeless, experienced hunger and thirst, abandonment, humiliation, being slandered, misunderstood, mocked, spit on, unjustly convicted, beaten and publicly executed. If that is what God allowed to happen to his son, what reason do we have to think that if those things happen to us, that God has failed us? Especially since Jesus himself warned us “that in this world you will have trouble”?

Again, I understand there are former believers who did have a more or less biblical conception of God and no longer believe in him for various reasons, some moral, some intellectual, some existential. But deconversion narratives reveal that for many that was not the case. Instead of rejecting the God of the Bible, they rejected a distorted version of him. One they received from their Christian community. Tragically, it implanted in them expectations for how God would act and what they could expect from him that ultimately went unmet. A crisis of faith ensued. We can do better. We need to pass on a biblical portrait of God and let the chips fall where they may.

RR: Back in the 1980s, I was a big fan of the Christian heavy metal band Stryper. And in one of their songs, “Reason for the Season,” they actually sang, “Everyday can be a holiday when he is with you.” Um, don’t tell that to Job! So I agree with you. When we sell people a false bill of goods, we set them up for failure.

JM: The lead singer of Stryper used to live not far from me out here in California. As a teenager I had their Soldiers Under Command, album. But I was more of a Petra guy.

RR: Respect!

Stay tuned for the third and final installment of our conversation.

The post The Solution to Christians Becoming Atheists (Part 1) appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 11, 2018

The Problem of Christians Becoming Atheists

A central goal of Christian apologetics is to persuade people to become and remain Christians. But what happens when that persuasion fails? In particular, what can we learn from those instances of failure when Christians reject the faith altogether?

A central goal of Christian apologetics is to persuade people to become and remain Christians. But what happens when that persuasion fails? In particular, what can we learn from those instances of failure when Christians reject the faith altogether?

In this conversation, I speak with Dr. John Marriott about the topic of Christians deconverting and becoming atheists … and what we can do about it. Needless to say, this is a hugely important topic, especially for anybody interested in apologetics, evangelism, or discipleship, and Dr. Marriott is ideally suited to address it. He is currently an adjunct professor in Philosophy and Intercultural Studies at Biola University and author of A Recipe for Disaster: How Parents and Churches Prepare Individuals to Lose Their Faith, And How They Can Instill a Faith That Endures (Wipf and Stock, 2018). You can learn more about Dr. Marriott online at https://www.johnmarriott.org/.

We cover a lot of ground in our conversation, and for that reason, I’ve divided our exchange into two articles. This article addresses the problem while the sequel will turn to address the solutions.

RR: John, thanks for joining us. Your major area of research has been focused on deconversion, specifically from Christianity to atheism. What is it that drew you to this topic?

JM: Thanks for having me. I think the short answer to that question is that in the midst of my doctoral program I stumbled across a website for former Christians. I was both intrigued and shocked at the number of former believers who had posted their deconversion stories. And not just nominal folks. There were former pastors, missionaries, worship leaders and seminary grads. It was troubling to say the least. So, I began looking into deconversion and what I found was captivating. The number of people who once identified as believers but no longer do is increasing at record numbers and record rates. I wanted to find out why? What did they know that I didn’t?

RR: That prompts several questions in my mind. But to begin with, could you say more about those record numbers? What kind of numbers are we talking about?

JM: Those are good questions. It’s always hard to determine exact numbers. And we all know that you can get statistics to say just about anything you want. But in the case of faith exit, it really does seem to be the case that people are leaving the faith in droves.

For example, In 2001, the Southern Baptist Convention reported they are losing between 70 and 88 percent of their youth after their freshman year in college. Of SBC teenagers involved in church youth groups, 70 percent stopped attending church within two years of their high school graduation. The following year, the Southern Baptist Council on Family Life also reported that 88 percent of children in evangelical [Baptist] homes leave church by the age of eighteen. The Barna Group announced in 2006 that 61 percent of young adults who were involved in church during their teen years were now spiritually disengaged.

Supporting Barna’s findings, a 2007 Assemblies of God study reported that between 50 percent and 67 percent of Assemblies of God young people who attend a non-Christian public or private university will have left the faith four years after entering college. A similar study from LifeWay Research that came out the same year claimed that 70 percent of students lose their faith in college, and of those only 35 percent eventually return. In May 2009, Robert Putnam and David Campbell presented research from their book American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites Us, to the Pew Forum study on “Religion and Public Life,” in which they claimed that young Americans are leaving religion at five to six times the historic rate. They also noted that the percentage of young Americans who identify as having no religion is between 30 and 40 percent, up from between 5 and 10 percent only a generation ago.

That same year, the Fuller Youth Institute’s study “The College Transition Project” discovered that current data seems “to suggest that about 40 to 50 percent of students in youth groups struggle to retain their faith after graduation. The 2010 UCLA study “Spirituality in Higher Education” found that only 29 percent of college students regularly attended church after their junior year, down from 52 percent the year before they entered college. A second UCLA study, “The College Student Survey,” asked students to indicate their present religious commitment. Researchers then compared the responses of freshmen who checked the “born again” category with the answers they gave four years later when they were seniors. What they found was shocking. On some campuses as high as 59 percent of students no longer described themselves as “born again.”

Given what we know regarding the loss of faith among American young people, it will come as no surprise that America’s Class of 2018 cares less about their religious identity than any previous college freshman class in the last forty years. A third study by UCLA found that students across the U.S. are disassociating themselves from religion in record numbers. “The American Freshman” study reveals that nearly 28 percent of the 2014 incoming college freshman do not identify with any religious faith. That is a sharp increase from 1971 when only 16 percent of freshman said they did not identify with a specific religion.

RR: Whoa, thanks for that helpful, if depressing, survey. So how widespread is the problem, geographically speaking?

JM: The focus of my research was on the United States. I have since broadened it to include Canada as well. Although I cannot prove it, I suspect that what we are seeing in the U.S. and Canada regarding the loss of faith is similar to the secularization process that has taken place in Europe. Although the prediction of Secularization Theory (as societies become more modern they will become less religious) has not been fulfilled on a global scale, it most definitely has proven to be true in the case of Europe. Canada is clearly following in Europe’s footsteps, and I suspect given enough time we will see a similar state of affairs in the United States.

RR: What are most of these people becoming when they deconvert? Do most become atheists? Or are many becoming “spiritual but not religious” nones?

JM: When individuals leave their Christian faith they have a number of new identities to choose from. They either become atheists, agnostics, “nones” or “spiritual but not religious.” The “nones” are not necessarily atheists. They may still believe in God but no longer identify with any kind of religious group. The “spiritual but not religious” folks are similar to the “nones” but they are more likely to be involved in spiritual exploration. It is hard to know how many former Christians are “nones” and “spiritual but not religious” and how many are atheists. Either way, there are large numbers of folks no longer identifying as Christians. My interest is in those individuals who were once committed Christians of an evangelical sort, that now identify as atheists. And by atheist I mean they no longer believe in God. They may either deny his existence or simply no longer affirm it.

RR: Thanks, that’s very helpful. So keeping in mind that we can only scratch the surface here, how about we proceed by first addressing a diagnosis and then a solution? With that in mind, what are some of the major factors you see behind this precipitous decline in the faithful?

JM: I think there are at least three factors. The first is mistaking a particular take or interpretation of Christianity for Christianity itself. This becomes problematic when the take or interpretation that is assumed to be Christianity elevates an excessive number of doctrines and practices to the level of the non-negotiable. This produces a house of cards faith. If an individual comes to reject any one of those doctrines or practices, the entire edifice will collapse.

RR: Like what?

JM: For example, a common refrain among the deconverted is that they were told that the creation account had to be a literal 6 day, 24-hour period of time. If not, the rest of the Bible had no foundation and thus no justification for it’s claim that we are sinners in need of a savior. When, for various reasons, they came to the conclusion that the universe was billions of years old they felt that they could no longer be Christians. For them, being a Christian meant “believing in literal 6 day creation”. In rejecting the young-earth view they assumed they were rejecting Christianity. In reality they were only rejecting a doctrinally bloated take on Christianity they mistook for the real thing.

RR: I couldn’t agree more. I regularly encounter people who left the church because of particular beliefs or practices that are far from what I would call mere Christianity. Young earth creationism is a great example, but there definitely are many others: everything from hell as eternal conscious torment to the idea that good Christians vote Republican.

So what’s next?

JM: The second factor is unmet expectations. When God and / or the Bible doesn’t live up to what deconverts expect a crisis of faith results. The problem, of course, is not God or the Bible but what many deconverts were taught to expect from the God or the Bible. One of the most common expectations that deconverts have is that the Bible is completely error free. And not just that it is inerrant but that it must be inerrant or else it cannot be the word of God. Somewhere along the way they were told that in order for the Bible to be the word of God it had to be free of error. Furthermore, the discovery of even one error would prove it wasn’t the inspired word of God. Eventually, they encountered what they believed was an error in the Bible. And, given what they assumed about the Bible, they were forced to conclude the Bible wasn’t God’s word. Rather than question the assumption of inerrancy, they took the more drastic action of concluding Christianity was a sham. The unquestioned assumption that the Bible is, and has to be inerrant, or else it cannot be the word of God, is the number one assumption / expectation that appears in deconversion narratives.

RR: Bart Ehrman is a great example. In his bestseller Misquoting Jesus he recounts how after studying at Wheaton College as an evangelical inerrantist, he came to study at Princeton. In one of his papers he focused on developing a long, convoluted argument that Jesus did not make a mistake in Mark 2 when identifying the priest during the time that King David ate bread from the temple. His prof responded to that long, convoluted argument with a simple observation: “Maybe Mark just made a mistake.” (Misquoting Jesus, 9)

Ehrman was initially very disturbed at this undeniably simple explanation. But eventually, he found himself considering that it was likely true: maybe Mark did just make a mistake. He then observes, “Once I made that admission, the floodgates opened. For if there could be one little, picayune mistake in Mark 2, maybe there could be mistakes in other places as well.” (9)

In Ehrman’s case, it’s easy to see how a particular understanding of inerrancy helped send his faith right onto the rocks of agnosticism.

So what’s the third example?

JM: Yes, Bart is a good example. In fact I tell his story in the book. It’s clear that he not only had misguided assumptions and expectations about the Bible, but also of God. When God did not live up to what his expectations he became disillusioned. The one-two punch of unmet expectations concerning the Bible and God can be fatal to faith.

The third factor is that we have not done a good job of communicating the content of the faith in what Charles Taylor calls “A Secular Age”. Taylor, as you know, argues that the conditions for what is believable in the modern West have radically changed. No longer is belief in God, or the truth of Christianity the default position in our culture. To the contrary, affirming even bare theism is difficult for educated, reflective, culturally aware folks. And believing in the God of the Bible can be downright embarrassing.

How, former Christians ask, can an intelligent, educated person accept the biblical story of two naked people, a talking snake and a magical tree, at face value given the world we live in? Or that a man lived inside a fish for three days, people lived over 900 years, and the dead come back to life?

What such questions reveal is that although deconvert’s understanding of reality became more nuanced, and sophisticated, as they aged and became more educated, their biblical understanding stayed at a simplistic, Sunday school level. Ultimately, they could not bridge the gap between having a “university” understanding of reality with their Sunday school concept of the contents of the Bible. For many former Christians, the “Old, Old, Story” sounded more like an ancient fairy tale than it did sober history. Believing in fairy tales is embarrassing. Children, not adults believe fairy tales, and no one wants to be considered an intellectual child.

RR: Well said. I like to say that we live in the age of the flying spaghetti monster, that is, an age in which Christian beliefs are viewed by many in the wider culture as arbitrary, absurd, and infantile. And when you grow up within a Christian subculture where your beliefs are rarely if challenged, it can be a real shock to the system when you first encounter the deep skepticism of many in the wider culture. It becomes even worse when you discover that many of those people are articulate and thoughtful and appear to have good reasons for what they believe.

Stay tuned for part 2 of our conversation, “The Solution to Christians Becoming Atheists.” And for a far more in-depth explroation of these issues, be sure to check out John Marriott’s new book, A Recipe for Disaster: Four Ways Churches and Parents Prepare Individuals to Lose Their Faith and How They Can Instill a Faith That Endures.

The post The Problem of Christians Becoming Atheists appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 7, 2018

How a “vaccine-hesitant” mom changed her mind, and what that can teach the apologist

In apologetics, arguments are important. But whoa man, disposition/attitude is even more important. If you want a great example of this point, please listen to this story from the CBC radio show “As it Happens.” Don’t worry: it’s only 7 minutes. Just broadcast yesterday, it tells the story of a “vaccine-hesitant” mother who was eventually persuaded that her concerns were unfounded. As she notes in the story, she had legitimate concerns about vaccines. And the pedantic and condescending way that healthcare professionals often dismissed those concerns merely served to retrench her in her suspicions.

This is not a psychological reaction that is restricted to vaccine-hesitant moms, by the way. We all tend to react negatively when people treat us in a pedantic and condescending manner. In this case, it was only when a fellow mom treated her with respect and dignity and then carefully addressed her concerns that this vaccine-hesitant mom changed her mind. (Alas, that change came a bit too late for her children, but you can listen to the show to learn more.)

Yes, folks, there is a life lesson here for all of us, and it is goes far beyond vaccines.

The post How a “vaccine-hesitant” mom changed her mind, and what that can teach the apologist appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 5, 2018

Can a subjective, private religious experience be veridical?

It has been a long while since I engaged anything written by John Loftus. (Though I still think our book God or Godless is an excellent primer to the God debates.) But today I decided to provide a response to a brief new article he wrote titled “Subjective Private Religious Experiences Prove Nothing!” As I said, the article is brief so I quote it in its entirety below (though I did not include the YouTube video that accompanies it):

‘Watch this!! Come on, come on! Come to your senses! Subjective private religious experiences provide no evidence at all that your religious faith is true. I’ve read the special pleading type of arguments attempting, but failing to show, these experiences are veridical, that if a god exists he can give you one. Sure, I’ll say it. If a god exists he can give someone a direct experience that he exists and his religion is true. But this gets you no where. It still doesn’t show that one particular god gave you the experience you claim to have had. The argument ignores the actual way people get these experiences and how they are used to defend all kinds of crazy religious faiths. The only way to know if your supposed religious experience is true is according to objective evidence evaluated dispassionately without any double standards, as an outsider.”

This paragraph is a litany of errors, but they are instructive errors and thus are worth engaging.

To begin with, we should set aside the tendentious restriction of religious experiences, and this for two reasons:

Vagueness: It isn’t clear what content would be required for an experience to be religious rather than non-religious.

Relevance: If there is a veridical problem here, it is a problem with subjective private experiences generally rather than with some specific subset of such experiences (i.e. religious ones).

In light of the second point, Loftus’ complaint about special pleading is ironic, to say the least: by restricting his discussion to a vague class of subjective private experiences, he is the one engaging in special pleading.

So here’s the question: can a subjective private experience provide evidence for a truth claim?

Let’s consider an example.

James decides to spend the night in an abandoned mental hospital that is rumored to be haunted. About 3 am, James wakes up in the darkness and senses a presence in the room. It’s an experience unlike any he has experienced before. Every hair is standing up, he is covered with goosebumps, and a chill goes down his spine. “Who’s there?” he says into the darkness. Suddenly, a figure materializes in front of him, levitating about 10 inches above the linoleum. It is the image of an incredibly sad woman with a severe head wound. Terrified, James runs out of the hospital. Days later, he identifies the apparition as a woman who died in the hospital in 1954 after being beaten in the head by another patient.

James underwent a subjective private experience. Could it provide evidence for James to believe that ghosts exist? Yes, of course it could. Could it provide evidence for other people, people who obviously did not have James’ experience, to believe that ghosts exist? Possibly so. That would depend on how they evaluated the credibility of James’ testimony relative to their background set of beliefs (i.e. their plausibility framework).

To sum up, Loftus’ claim is false. Subjective private experiences can provide evidence to accept (or retain) a particular truth claim. Of course, Loftus could claim that this is not true of that specific subset of subjective private experiences which are religious in nature. But first, he would need to overcome the vagueness problem by explaining what it is the makes an experience religious. Next, he would need to explain what specific problem applies to all subjective private religious experiences but not to subjective private experiences generally.

The post Can a subjective, private religious experience be veridical? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 3, 2018

Atheism and the Desire for Privacy

He sees you when you’re sleeping

He sees you when you’re sleeping

He knows when you’re awake

He knows if you’ve been bad or good

So be good for goodness sake

Those lyrics have disturbed generations of children, and for good reason, too. There is something unsettling about the idea of a person, even a right jolly old elf, who knows everything — and I do mean everything — about you.

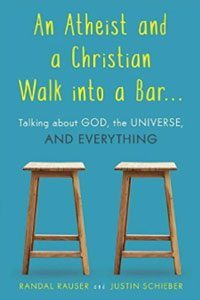

But does that basic intuitive reaction provide a reason to hope that atheism is true? In this excerpt from my 2016 book An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Bar, my coauthor Justin Schieber argues that the desire for privacy provides a prima facie reason to hope that atheism is true. Not surprisingly, I disagree.

Randal: Christopher Hitchens (may he rest in peace) used to love comparing God to a despot like Kim Jong-il of North Korea. For Hitchens, living under God would be living under cosmic tyranny. So, not only did he believe God didn’t exist, he also hoped he was right, and he was prepared to rebel against any God that should appear on the scene.

Justin: Very true. For Hitchens, the wish for God to exist was the wish to be a slave. In a 2008 debate with his brother, Peter Hitchens, Christopher proclaimed the following:

“It [a desire for God to exist] is the desire for an unalterable, unchallengeable, tyrannical authority who can convict you of thought crime while you are asleep . . . who must indeed subject you to total surveillance around the clock, every waking and sleeping minute of your life, before you are born and even worse, and where the real fun begins, after you’re dead. A celestial North Korea. Who wishes this to be true? Who but a slave desires such a ghastly fate?”

Beyond the master/slave rhetoric, which I think is without merit, there exists, I think, a legitimate concern about theism. If theism is true, it does rob us of any sense of privacy. Our thoughts are not our own. So, while I agree that, all things considered, we have more to gain if theism is true and so should prefer that be the case, this is one issue that seems to bring at least some support for the opposite conclusion. Would you agree, Randal?

Randal: That reminds me of the story of average guy Alex Moss. When he was remodeling his bedroom, Mr. Moss found the following note hidden in the fireplace: “Hello, welcome to my room. It’s 2001 and I am decorating this room. Hope you enjoy your life. Remember that I will always be watching you.”

Always watching?! Brrr. Moss thought that was sufficiently weird to share the story online. And it quickly went viral, as people reflected on how creepy it would be to have somebody always watching you. So I get where you’re coming from.

Having said that, let me answer your question. No, I don’t agree with the objection as applied to God, because it seems to be based on a crude anthropomorphism. That is, it arises from the error of uncritically thinking of God in human terms, as someone like the mysterious voyeur who formerly lived in Alex’s bedroom. An invasion of privacy occurs when another agent surveils your actions, as in a peeping Tom peering through your blinds or a secretive government agency listening to your phone calls or reading your emails. But God’s knowledge of us is nothing like that. God doesn’t surveil your actions. That is, God doesn’t gain new information about his creatures by surreptitiously observing them. Rather, as a necessarily omniscient being, God simply knows all true statements from eternity.

Since God’s knowledge of us has no relation to the peeping Tom or secretive government agency, the suggestion that God invades our privacy just strikes me as confused.

Justin: Hmm. I can agree with you that you’ve identified a difference between God’s knowledge of all events and typical cases of human knowledge. But why should we think that distinction is of any relevance? For it seems to me that, however the knowledge is gained, the fact that our thoughts are not ours alone still remains and that fact should at least count for something.

Randal: What do you mean “our thoughts are not ours alone”?

Justin: Simply that we cannot be alone with our thoughts. With theism, we lack all privacy of mind.

Randal: It seems that your language gains in poetic panache what it loses in analytic precision. To be frank, I’m still unclear why you believe that a necessarily existent being’s knowledge of all true propositions constitutes an invasion of your privacy.

Let me try a different angle: A few years ago, I learned that there are tiny creatures, creatures that are too small to be seen by the human eye, that live on the human forehead.

Justin: Gross.

Randal: That’s what I said!

Justin: What are they?

Randal: Unfortunately, finding out the answer didn’t make me feel any better. Demodex have eight legs and long chubby bodies, and they live their entire lives crawling around near our eyebrows. At first, this revelation was so repulsive to me that I had to fight the urge to dip a hunk of steel wool in bleach and go to work on my forehead.

But lo, over time I’ve grown accustomed to the idea of those critters living on my forehead. If I can get used to the prospect of something as unsettling as bugs living on my face, I think you can get used to the prospect of a morally perfect, necessary being knowing all true propositions from eternity, including whether you will have pastrami on rye for lunch next Tuesday.

Justin: I’m not claiming that it would be perpetually terrible if God were to exist. Remember, I still think it would be a good thing, all things considered, for God to exist. I am simply claiming that this is at least one reason, however small you think it is, to wish that God didn’t exist. The fact that I could get used to it after a while doesn’t negate the fact that it is one relevant factor. I might get used to the fact that a neighbor can hear me making love, but I may still think of this as a reason for preferring they didn’t live on the other side of the wall!

Randal: Once again, you’re falling into the anthropomorphic trap of envisioning God taking in knowledge about his creatures through some kind of external perception. But it’s not like that. God doesn’t observe us by hearing or seeing what we’re doing through a wall. God does not surveil us to gain knowledge of us. That’s not how omniscience works.

Anyway, the reason I brought up the point of getting used to Demodex living on my forehead is to illustrate that in retrospect my initial revulsion at these creatures was misplaced. In fact, they don’t impinge on my enjoyment of life, and it just took some time to realize that fact.

Similarly, I think that once you recognize that God isn’t the North Korean despot of Christopher Hitchens’s imagination, you can likewise see that a divine being’s knowing all true propositions from eternity is not, in itself, ground to worry about an invasion of one’s privacy.

The post Atheism and the Desire for Privacy appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 1, 2018

21st Century Martyr: A conversation on the legacy of John Allen Chau

John Allen Chau: disciple, missionary, martyr (1991-2018)

On November 17th, 2018, 26-year-old Christian missionary John Allen Chau was killed while attempting to evangelize the native Sentinelese people of North Sentinel Island, India. The wake of the tragedy has seen intense global media interest in the case, with many people dismissing Chau as a fatuous thrillseeker, a dangerous zealot, a subversive colonialist … or all of the above.

However, not all assessments have been negative. In his fascinating article “Should Missionaries Just Stay Away?,” theologian and professor John Stackhouse offers a very different assessment of Chau as a “brave young man doing what brave young Christians should.” In this conversation, I spoke with John about his article and the issues it raises.

RR: John, thanks for writing your article “Should Missionaries Just Stay Away?” It’s a very interesting defense of John Chau’s evangelistic efforts and one that was well worthy of further reflection. So for starters, what prompted you to write this article?

JS: I read a piece issued by a prominent American medium (Religion News Service) that was really badly written, a hodge-podge of fact, stereotype, and outright falsehood that almost certainly was published only because the author identified herself as both a former evangelical Christian and a Native American wrestling with her own identities as such. I sincerely sympathize with people sorting out such intersectional challenges, but it’s best if they don’t publicly slag whole communities (e.g., evangelicals, missionaries) while they do so–and she did. Essentially, because missionaries have often been implicated in colonialism, then John Allen Chau was an imperialist because he was a missionary. That’s a logical problem of a pretty basic order, of course, and it’s also a wild overstatement about the history of missions. So I thought, since I’m something of an authority on evangelicalism and I’ve taught the history of missions, I might usefully speak up on these matters.

RR: Thanks, that’s helpful. I find the Chau case fascinating because it brings together a broad nexus of complex issues and I’d like to pick your brain on some of them. I’d like to start with what seems to me to be a shift in the way many evangelical Christians view pioneering missionaries and their work.

Back in 2002 when I was teaching at Briercrest College, I met Bruce Olson during his visit to deliver some guest lectures. Olson was made famous for his work with the Motilone people of Colombia and Venezuela and I had held him in high esteem since I’d read his autobiography Bruchko as a kid. Indeed, growing up, people like Olson were the closest thing to an evangelical saint.

In your article, you make reference to another famous evangelical missionary, Jim Elliot, who was martyred in 1956 while attempting to evangelize the Huaorani people of Ecuador. For generations, Christians like Olson and Elliot have represented the noblest expression of the evangelical aspiration to follow Christ.

One thing that struck me about the reaction to Chau was how many Christians, and evangelicals in particular, seemed to be dismissive of and even hostile toward his efforts. Do you think that there has been a shift in attitude toward the work of the pioneering missionary? And if so, what do you suppose is driving it?

JS: There aren’t many heroes left outside superhero comics and movies, are there? Not unalloyed saints, that’s for sure. And that’s okay: No one but Jesus has been perfect, and we’re right to keep our critical faculties about us even when, and sometimes especially when, someone is presented to us in glorious robes of sanctity.

That said, I agree that it’s weird, verging on the pathological, the way even fellow Christians have sharply criticized this young man, initially assuming he was a fanatic who knew nothing about diseases (wrong), languages (wrong), tribal cultures (wrong), and the dark history of imperialism (wrong). In fact, he and his sending agency seem to have been impressively responsible on all those counts. So what’s the problem?

Then we have evangelical Christians chiding him for breaking the law in preaching the gospel to people the government had said were off limits. Excuse me? Anyone read the Book of Acts recently?

The most serious charge is that the islanders had made it clear they didn’t want anyone from the outside to visit. Given what seems to have been their awful experience of British colonialism a generation ago, no wonder they didn’t. But does that mean no one ever brings them the benefits of modernity, condemning them–and their children–to a life without analgesics, anaesthetics, and antibiotics? Without refrigeration and metal tools and shoes and dentistry and books? Why not attempt to give them positive experiences, rather than just saying, “Oh, well, they don’t want our help.” That’s like leaving a traumatized kid in the basement of his tormentor’s house while making sure only that the tormentor is gone.

So was Chau foolish to go in alone? Some Christians are criticizing him for breaking the missionary “rule” they derive from the Bible about going in twos. But that was once or twice in Jesus’s own ministry. Jesus himself spoke alone to the woman at the well, Philip was directed by the Spirit to speak alone to the Ethiopian eunuch, Paul presumably spoke alone to his jailers (!), and so on, and so on. Indeed, one might make the case that Chau was so aware of the islanders’ fear of outsiders that he went to them as non-frighteningly and non-imperialistically as he could: by himself, unarmed, utterly vulnerable. What should he have done? Go in heavy with a commando team? Sheesh.

RR: One of the fragments of Chau’s story that has courted controversy is the fact that in the days prior to his death, he wrote in his journal, “Lord, is this island Satan’s last stronghold where none have heard or even had the chance to hear your name?” Unfortunately, but not surprisingly, many people seem to have thought that language quite literally demonizes the people to which Chau was ministering. But from the perspective of an evangelical Christian, that is familiar spiritualized language of concern for people who have never heard the Gospel. You’ve already touched on the ways that Chau was misunderstood (e.g. weird, imperialistic) but perhaps you could say a bit more about that with an eye to the wider cultural perception of evangelicals.

JS: Biblically speaking, Chau’s language is unusual–the Bible doesn’t mention Satan very often–and evangelicals nervous about their public profile might want such language tamped down. But it isn’t wrong. In this world, Satan rules where Jesus doesn’t. Why Chau is asking that question of the Lord isn’t obvious. Maybe he subscribes to the idea that the Lord will return once everyone on earth is evangelized. But he’s not wrong to wonder about the islanders, given how few “unreached peoples” are left on earth, and he’s not wrong to phrase it that way.

RR: You say that Satan rules where Jesus doesn’t with the implication being that Satan rules in lands where the Gospel has yet to be proclaimed. However, many Christians would push back against this framing of the issue. For example, at Vatican II, the Catholic Church embraced Karl Rahner’s idea of anonymous Christians, people who are following Christ even prior to having heard the Gospel. If one takes that inclusivist view of salvation, namely that salvation can include those who have not yet heard the Gospel, then one might not be so quick to judge a society as Satan’s stronghold prior to the verbal proclamation of the Gospel.

What are your thoughts on the exclusivist/inclusivist debate and how it might shape the way we interpret the actions of a missionary like Chau?

JS: Thanks for this push-back. Let me be more clear. “Jesus is Lord” is the earliest confession of the Christian Church and the foundation of the Christian view of things. Satan rules only to the extent that Jesus allows him to–and, indeed, to the extent that we human beings, who were originally supposed to govern the earth under God, allow him to.

When I say that “Satan rules where Jesus doesn’t,” I mean that in situations in which God’s way is not followed, Satan holds sway. (In this locution I am not distinguishing “Jesus” from “God.”) But that doesn’t mean that Satan rules everywhere that isn’t explicitly Christian, and in two respects.

First, I agree with you that there are individuals, families, and even whole tribes that have come under the influence of the Holy Spirit such that they are reconciled to God (through the work of Jesus, to be sure) even though they haven’t yet heard the actual story of Jesus. (I hold to evangelical inclusivism, to use the theological terminology.) So just because a person, family, or community isn’t yet Christian doesn’t mean Jesus isn’t already ruling there.

Second, there are individuals, families, and whole communities that call themselves Christian and manifestly disobey Jesus and instead pretty clearly follow the way of the Adversary.

What I meant, then, and what I mean is that in the final analysis, we human beings serve one lord or the other. Since the Sentinel Islanders, about whom we know only a little, to be sure, seem not to practice Christianity or anything like it, Chau appropriately wondered about their spiritual status. But it is important to note that he is wondering, he is asking the Lord a question, not pronouncing from afar on their spiritual status.

RR: Much of the negative reaction to Chau has been based on the assumption that his actions were impulsive and unplanned. But that is most certainly not the case. Mary Ho, the head of All Nations, the mission agency that sent Chau, pointed out that Chau had sensed a calling to the North Sentinelese since he was a teenager. She observed: “Even as a young man, before we met him, every decision he made, every step he took, was to share the love of God with the North Sentinelese.”

Could you say something about the concept of calling and particularly the notion that God might call his children to acts of service that could involve mortal peril?

JS: What John Chau seems definitely not to have been is impulsive. Instead, he was resolute. He might have been wrong–any of us can be, even about important things about which we have prayed. But he was following what to him was a path blessed by God: a sense of calling, an opportunity to train properly with a responsible mission, and even fishermen willing to transport him secretly to the island. At any point, God could have put a halt to Chau’s dream. And when his first attempt ended with an arrow through his Bible, lots of his critics have said he should have quit then and there. But why? The islanders were behaving exactly as Chau would have expected them to. So why quit?

Missionary history is in fact full of stories of pioneers cut down upon first contact, only to be replaced by more who were inspired by the initial story who then enjoy success. Let me be clear that of course I am not defending any and all missionary endeavours. Some of them have indeed seemed foolish and fruitless. But I am defending the simple point that someone has to be first, and that someone may well pay the ultimate price in order to get the conversation going. That’s what John Chau did, and it’s ‘way too early to write off his self-sacrifice as foolish and worthless. Let’s just see what happens next.

Last point: For Christians, the worst thing in the world isn’t dying. It’s failing to do the will of God. John Chau, by those principles, made the right choice. That’s why I call him a martyr.

The post 21st Century Martyr: A conversation on the legacy of John Allen Chau appeared first on Randal Rauser.

November 30, 2018

Would you support a Muslim charity if it was more effective than a Christian one?

Here’s the situation I’d like to pose to my fellow Christians: when engaged in charitable giving, do you value the Christian status of an organization over the efficiency of that organization? And if so, by how much?

That’s the general question, but now let me dress it up with some specifics.

A terrible earthquake with multiple casualties has occurred in a part of the developing world and you have the opportunity to offer support to the first responders/relief workers by way of a monetary donation. There are two groups working in the region and thus two possible ways to bring relief to the people: one of those groups is a Christian NGO and the other is a Muslim NGO.

All things being equal, it is natural for Christians to support the Christian NGO. But in this case, all things are not equal. You have reliable information that these organizations differ in their donation usage as follows:

Christian NGO: 20% to administration; 30% to promotion; 50% to the people in need.

Muslim NGO: 10% to administration; 15% to promotion: 75% to the people in need.

In short, if you donate to the Muslim NGO, you give up the benefit of having tied to a Christian proclamation. But you also gain the benefit of an organization which is substantially more effective at providing the stated purpose of both NGOs, namely of providing relief aid to those in need.

With that in mind, which organization do you support, and why? Share your thoughts below and feel free to contribute to the Twitter survey as well.

A survey for Christians: when engaged in charitable giving, do you value the Christian status of an organization over the efficiency of that organization?

Please read the scenario at this link (it's brief) and then respond to the survey.https://t.co/kkIF1KZi3L

— Tentative Apologist (@RandalRauser) November 30, 2018

The post Would you support a Muslim charity if it was more effective than a Christian one? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

November 26, 2018

Do bad children go to hell?

When I first became a father, I found myself facing a question that most Christian parents must confront at one time or another: when is my child responsible to make her own decision to follow Jesus? Were thirteen-year-olds in danger of going to hell? And what about a three-year-old? What was the point at which a child who failed to trust in Jesus could be damned for that failure? When I first held that swaddled bundle in my arms, these questions were no longer merely academic. After all, my daughter’s eternal life could depend on getting the right answer!

When faced with such disturbing questions, the Christian tradition has commonly taken solace in the idea of an age of accountability. According to this notion, children are born into the world with a divine grace period which provides them time to grow and mature. During this early period, children are not held responsible for their beliefs and actions. But once they mature to a particular age, they cross a threshold into accountability after which they are responsible to make their own decision to follow Jesus … or face damnation.

It might help to think of this idea of an age of accountability in analogy with the age of majority, that legal threshold which demarcates the move from childhood to adulthood. The transition into the age of majority is significant for a number of reasons. For example, a person is not legally responsible for a contract they sign when they are still a legal minor. But the moment they become a legal adult, they are responsible. Further, criminal responsibility varies as to whether the crime was committed when the individual was a legal minor or an adult. For these and many other reasons, the age of majority is enormously significant.

While the age of majority is clearly significant, it pales in importance when compared with the age of accountability. According to this concept, children are born heaven-bound by God’s mercy, but there will soon come a day when they will become morally accountable for the lives they lead. At that point, their salvation will require a personal decision to follow Jesus.

So what does the Bible say about the ages of innocence and accountability? The answer is, surprisingly little. The most commonly cited text in favor of the age of accountability is found at the moment when King David’s newborn child dies. In response, David stoically observes: “now that he is dead, why should I fast? Can I bring him back again? I will go to him, but he will not return to me.” (2 Samuel 12:23, NIV 1984) Here David seems to express the conviction that he will be reunited with his child again. If we think of that reunion as occurring in heaven, then David’s sentiment would suggest an age of innocence, at least for newborn infants.

However, even if we accept that interpretation, it still doesn’t tell us much. After all, the passage only applies to newborn infants: the text says nothing about toddlers, small children, or teenagers. As a result, once we attempt to extend an age of innocence to a wider pool of individuals, we are moving well beyond David’s prayer and into the realm of hopeful speculation. And few parents will be content to leave the salvation of their beloved children to the realm of mere speculation.