Randal Rauser's Blog, page 86

January 16, 2019

Why Every Christian Should Be a Hopeful Universalist

Here is a new video I uploaded to YouTube in which I discuss the concept of hopeful universalism. For further discussion, see chapter 20 of my book What On Earth Do We Know About Heaven? which is currently only $3.99!

The post Why Every Christian Should Be a Hopeful Universalist appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 13, 2019

“Nihilism is false iff theism is true”: Let’s Discuss

When people say atheism entails nihilism they're more than likely saying "I'll be really sad if I couldn't believe I'm immortal and will eventually live in paradise."

— Counter Apologist (@CounterApologis) January 13, 2019

I like Counter Apologist, but this is akin to saying “When people say ‘God doesn’t exist’ they’re more than likely saying ‘I don’t want to submit to God.'” Rather than engage in gratuitous armchair psychologizing, we should just take what folks say at face value.

So here’s the Nihilism Thesis:

(NT): Nihilism is false iff* theism is true.

Should we accept (NT) and if not, why not?

To grapple with this question, we should say something further about the two concepts, nihilism and theism. For the purposes of this discussion, these are my definitions:

Nihilism: The belief that there are no objectively true principles of moral value, obligation, meaning, or purpose and thus life is objectively meaningless.

Theism: The belief that the ultimate necessary principle of all existence is a maximally great and perfectly good person who created and sustains all things and who is the objective ground of human meaning and purpose.

Based on those definitions, should we think that (NT) is true or false? Or should we be agnostic? And what about the definitions themselves? Are they adequate? If not, why not?

*In case you were wondering, iff is not a typo; rather, it is a nerd-abbreviation for “if and only if.”

The post “Nihilism is false iff theism is true”: Let’s Discuss appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 12, 2019

The Meaning and Rationality of Faith: A Christian and Atheist Conversation

Christians and atheists often engage in heated debate over the rationality of faith. Unfortunately, those conversations tend to generate more heat than light, not least because the parties to the discussion often end up talking past one another. If we want to make real progress on debating the rationality of faith, we should begin by considering what we mean when we use the word ‘faith’. Just what is that concept that we are debating?

Christians and atheists often engage in heated debate over the rationality of faith. Unfortunately, those conversations tend to generate more heat than light, not least because the parties to the discussion often end up talking past one another. If we want to make real progress on debating the rationality of faith, we should begin by considering what we mean when we use the word ‘faith’. Just what is that concept that we are debating?

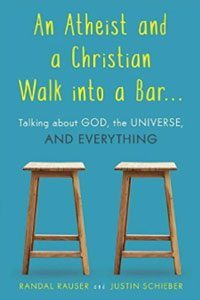

The following article on faith is excerpted from the book An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Bar. In the book, atheist Justin Schieber and I engage in one long conversation talking about God, the universe, and, well, everything. One of the aims of the book is to stem the tide on the unfortunate tendency to talk past one another by modeling careful listening and generous exchange. In this case, we turn our attention to the meaning and rationality of faith.

Randal: Perhaps we can switch gears at this point and turn to defining faith. Just as there are many different definitions of God, so there are many different definitions of faith. In particular, there are two basic ways the word faith is defined, and they are often conflated in discussions like this. So it’s probably worthwhile to be clear on the distinction.

Justin: That’s a good point. That word gets thrown around a lot, and it’s not always clear what usage is intended.

Randal: In the first sense, faith is roughly equivalent to religion. Insofar as we are working with that definition of faith, it’s clear that some people have faith and some don’t because some people are adherents to a particular religion, while others have no religious affiliation.

Justin: Right. As with the phrase, the Abrahamic Faiths.

Randal: Yup. In this sense I’ve got a faith (Christianity), but you don’t. And in the second sense, faith is roughly equivalent to trust. In other words, to have faith in something is to trust in that thing. If I have faith in the truth of a proposition, then I trust that the proposition is true. If I have faith in a person, then I am inclined to trust what this person says as being true. If I have faith in my cognitive faculties, like sense perception and memory, then I trust that the

deliverances of these faculties are generally reliable.

Justin: That makes sense.

Randal: I think it’s important to make this distinction clear because I often hear those without a religious faith (the first definition) insist that they don’t have faith in something like the second sense. But this is simply false. Whether you have a religious affiliation or not, everybody must still trust in some truth claims, in particular persons, and in the very cognitive faculties that mediate information about the world to us. There is no view-from-nowhere that allows us to test our beliefs apart from faith. So only some of us have faith in the first sense but everybody has faith in the second sense.

Justin: I suspect that the nonreligious community would rather use trust than faith when speaking of confidence in some proposition or person because of faith’s religious connotations. But it’s certainly the case that the word can be used in both senses.

Randal: While some folks may feel better about using the word trust, the truth is that there is nothing especially religious about the term faith. Just listen to George Michael’s 1987 hit song “Faith,” in which the pop star’s call to have faith is focused on a lowbrow desire for sexual contact with a woman. Needless to say, there are no lofty religious convictions in that use of the word.

The lesson is that the very common tendency to pit faith against reason is wholly mistaken, for reason always begins in faith or trust. This reality goes straight back to our earliest formation as infants and toddlers, as we extended trust to our caregivers to mediate information about the world to us. Indeed, I like to describe faith and reason as the two oars of a boat. If you only row on one side of the boat, you go in circles. You need faith and reason together to advance in your understanding of the world.

Justin: Thank you for that important distinction. A core takeaway here is that, whatever word we might prefer to use when talking about confidence—be it faith or trust—not all confidence is equally rational.

But, at this point, I’d like to make a related and important point: the rationality of one’s faith or trust in, say, the goodness of a person, the usefulness of an idea, or the accuracy of a text can exist in degrees that can change over time.

In the case of the parents who turned a blind eye to the incriminating evidence against their two sons, they had faith or trust in their children’s innocence. It might be the case that their trust was the rational result of consistent saintly behavior from the two brothers until the night in question. If it were, their faith in the innocence of their children was well-placed, given the information to which they had access at the time.

Where they erred was not in their original faith or trust in the innocence of the defendants. Rather, their mistake was when they let this supreme confidence in the innocence of their sons get in the way of updating their current belief with important additional information from the prosecutor.

Randal: Yup, and this is one of the places where I think folks often get into trouble when judging the rationality or objectivity of other folks. The problem comes when we judge the rationality of other people based on the set of beliefs we hold. That’s a mistake.

Justin: I agree, and it’s a very common mistake. The question is not whether or not some particular belief is rational, the question is rational for whom? Some beliefs can be rational for some persons but irrational for others.

Randal: Right. And this is a point worth underscoring with an example, one that brings us squarely back to theism. Let’s say, for example, that Pastor Jones prays for his daughter to recover from a bad case of pneumonia. A couple of hours after the prayer, the daughter begins to show dramatic signs of improvement.

By the next day, she is fully recovered, and Pastor Jones concludes that God healed her. I have often heard religious skeptics reply that this kind of interpretation of the recovery is irrational because the child’s improvement could just as well be due to chance. I agree that it could be chance: nobody’s denying that. However, we should also remember that Pastor Jones starts out with different background beliefs from the skeptic. Pastor Jones believes there is a God who answers prayer, while the skeptic doesn’t believe this. Since they have different starting points, each reasonably interprets the same data differently relative to their background assumptions. As a result, the pastor can see the hand of providence while the skeptic sees mere serendipity.

So here is how this cashes out: it is reasonable for Pastor Jones to attribute the recovery to divine action, and it is reasonable for the skeptic to attribute it to chance. The point is that we don’t need to decide which interpretation is reasonable or justified. Rather, Pastor Jones and the skeptic can both be reasonable in interpreting the data differently, each in accord with his background beliefs.

The post The Meaning and Rationality of Faith: A Christian and Atheist Conversation appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 11, 2019

How I wore evangelistic T-shirts in high school to try and save … myself

In my book What’s So Confusing About Grace? I journey through several different ways of thinking about salvation that I held growing up (and into adulthood). Along the way, I summarize several “laws” that I came to believe were essential to salvation, including that which I call “Law 5”:

Law 5: If you are ashamed of Jesus, then Jesus will be ashamed of you. And if Jesus is ashamed of you, then God will send you to hell, even if you’ve already followed the other four laws.

I haven’t been able to find a picture of my old JC/DC shirt online, but this graphic is very similar. (Source)

Law 5 meant that you had to undertake supererogatory acts of evangelistic proclamation in order to try and make sure you were saved. The article I included below is an excerpt from the book in which I describe my tortured teenage logic that sought to meet the demands of law 5 by wearing … an evangelistic (JC/DC) T-shirt.

Living Epistles T-shirts featured cheesy Christian puns melded with pop-culture references, to the end of fulfilling the Great Commission. I guess the point of the shirt was to provide a disarming way to initiate life-changing conversations about the Gospel. (In retrospect, I suspect the real effect was to serve as a warning: Beware, evangelical Christian approaching!)

Perhaps I should give you an idea of what I’m talking about. One shirt looked like the “Gold’s Gym” logo except it said “Lord’s Gym” and it depicted a buffed Jesus raising a cross emblazoned with the sins of the world. The accompanying line said: “Bench press this!” As if that weren’t bad enough, the back of the shirt showed a nail through a hand with the logo: “His pain, your gain!” (Subtlety was not the specialty of Living Epistles T-shirts.)

The shirt I bought came in basic black and was designed to look like a concert T-shirt for the heavy metal band AC/DC. But instead of the AC/DC logo, the blood red letters spelled out “JC/DC.” And what, you may ask, is “JC/DC” supposed to refer to? Um yeah, underneath the logo the caption read “Jesus Christ / Divine Current.” Although I never admitted to my motivations for buying this wince-worthy shirt, the truth is I got it to meet the demands of the fifth law. Surely if I was willing to walk down the halls proclaiming that Jesus is the “Divine Current” he could hardly tell God the Father that I was ashamed of him.

The only problem was that I was kind of ashamed.

Yeah, I know. Shocking.

But before you judge me too harshly, let me add that I think I was more embarrassed about the T-shirt than Jesus. I really did think Jesus was cool. But the T-shirt most definitely wasn’t. Nonetheless, even if my issue was with the shirt rather than the savior, I wasn’t sure that Jesus would be able to tell the difference. So I faced a crucial question: how could I embolden my witness? And how could I do it without completely sacrificing the modest social capital I had acquired with my peers? (Never underestimate the value of social capital to a teenager.) In retrospect, I was desperate to find some sort of loophole, a way to proclaim the Gospel boldly while minimizing the chance of mockery, personal humiliation, and social exile. But how?

Eventually, I lighted upon what I believed to be the perfect solution: I’d wear the JC/DC shirt to school alright, but I’d wear it underneath a flannel shirt. Of course, I recognized that I couldn’t cover the JC/DC shirt up completely, for that would obviously defeat the purpose. And so I decided to leave the flannel shirt unbuttoned so people would still be able to see the JC/DC logo underneath . . . at least partially. And this brings me to the real bit of genius: as the flannel shirt hung over my shoulders it would obscure the outer letters of the Living Epistles proclamation, leaving only the middle “C/D” visible to passerby. As a result, everyone would assume I was just wearing a regular AC/DC shirt when in fact I was boldly proclaiming Jesus Christ as the divine current.

Oh yeah! Absolutely brilliant, right? I had discovered a way to proclaim my faith boldly while retaining my dignity in the process! It was the perfect compromise. People who thought you couldn’t have your cake and eat it too had obviously never met me.

In short, I had squared the evangelistic circle.

Or had I? I didn’t know the word “casuistry” at the time, but looking back, it now seems that this so-called solution to my problem perfectly exemplifies it. Casuistry (at least in the form I was pursuing it) is the act of seeking extremely clever (if contrived) solutions to moral problems, solutions which are based on the search for loopholes as a way to follow the letter of the law while avoiding its spirit. Picture, for example, an older brother who is beating on his younger sibling. The mother calls out sternly: “Hey, stop punching your brother!” And so, the older sibling obediently stops throttling the poor kid . . . and shifts to kicking him instead. The casuist might be inclined to say that technically that boy followed his mother’s direction. But if he did follow her words, he surely ignored the spirit of her request. That’s a good example of a casuist’s subversion of the intent of the law.

When it came to the fifth law, I understood the demand to require extraordinary acts of evangelistic proclamation . . . acts like wearing a Living Epistles T-shirt. I believed that just as Christ had gone above and beyond to offer salvation, so I was now expected to return the favor by going out of my way to proclaim Jesus to the world.

And just so we’re clear, that’s an eminently reasonable demand, so it’s not like I’m complaining. To put it into perspective, it’s kind of like accepting a free Dyson vacuum cleaner on the condition that you agree to share the virtues of your new Dyson with your friends. Consequently, if you never speak a word of your great new vacuum cleaner to others, if you blush when they talk of the joys of owning a Hoover, if you remain silent when they lament their hopelessly soiled carpets, then it’s only right that you should give the Dyson back. After all, you didn’t uphold your end of the bargain: the least you can do is preach the virtues of the Dyson to family and friends!

Salvation was like that: it was a bargain, a reasonable quid pro quo: Jesus saves you, and all you need to do in return is tell your friends. Surely that isn’t asking too much. So if you don’t want to do at least that, if you don’t want to uphold your end of the bargain, then you can jolly well give your salvation back.

In terms of boldly sharing the virtues of Jesus with friends, wearing an emblem on my chest which attested to the divine current otherwise known as Jesus certainly seemed to qualify. So I wore the T-shirt to school. As for the flannel shirt that suspiciously obscured my witness, I rationalized the additional layer by noting that the school halls could be drafty and I didn’t want to catch cold. (Seriously, I told myself that.) While wearing the flannel shirt may have undercut the effectiveness of the proclamation, in my casuistic rationalization I had persuaded myself that this would still somehow qualify as boldness on Judgment Day.

Yeah, good luck with that.

The post How I wore evangelistic T-shirts in high school to try and save … myself appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 9, 2019

Philosophy and Magic: What’s the difference?

It all started with my Wittgenstein tweet. That prompted a reply from philosopher and atheist, Stephen Law and in a moment we were off discussing philosophy vs. magic. I divided our flurry of tweets into two tracks dealing with the two issues I raised. Blessedly, we ended on some point of agreement. Score one for civil discourse! Indeed, given the reasoning evidenced by both parties, I’d say we even did some philosophy!

Randal Rauser: Ludwig Wittgenstein: “We feel that even if all possible scientific questions be answered, the problems of life have still not been touched at all. ” (Tractatus, 6.52)

Stephen Law: That’s why we have 1. philosophy, and 2. magic books.

RR: What’s a “magic book”?

SL: Well a sufficient condition would be a book that is supposed to provide answers to ‘Big Questions’ not by applying science and/or reason but by the operation of some sort of supernatural and/or otherwise mysterious revelatory mechanism, e.g. a sensus divinitatis.

RR: 1. If a person appeals to moral intuitions or rational intuitions in their argument, are they appealing to a “mysterious revelatory mechanism”? If not, why not? 2. What makes something “supernatural”? Does David Lewis’ account of possible worlds apply? If not, why not?

Point 1: Magic

SL: 1. Thought you’d raise that. A book that develops a reasoned case based on what is admitted to be e.g. a strong moral intuition is IMO a work of philosophy, whereas a book that just makes a series of claims supposedly grounded in such a mechanism is not (e.g. Nostradamus).

RR: You identify 2 criteria: (i) a reasoned case, (ii) appeal to a strong intuition. Does (ii) depend on *you* recognizing that intuition as strong? Or could that reasoned case be philosophy even if you don’t recognize that intuition?

SL: not sure I understand the question.

RR: You referenced the “Sensus Divinitatis” as an example of a source of properly basic belief (i.e. intuition) that you don’t share. Thus, you deem that a “magical” source of belief that negates the philosophical value of all reasoning that depends on it. Not so for moral intuition?

SL: If a book makes a sophisticated argument drawing on premise that is claimed to be some divinely (thus magically) provided truth, I’d class that as a work of philosophy. A ‘magical’ book is one is primarily in business of making magically revealed claims (e.g. Nostradamus).

RR: Ah, okay, so a would-be prophet like Nostradamus produces a “magic” book, but a philosopher like Alvin Plantinga who explicitly reasons in accord with his worldview (including intuitions he believes derive from a sensus divinitatis) is doing philosophy. We agree!

SL: Yeh, that sounds right. But now we’ll probably disagree about The Bible, The Quran, etc. Magic books.

RR: We might indeed disagree re. the Bible. Yoram Hazony makes an excellent case that the Hebrew Bible is full of philosophy: e.g. political philosophy in the Deuteronomic history, epistemology in Jeremiah etc.

But we can agree to disagree on that. Cheers!

Point 2: The Supernatural … and Magical

SL: re 2. I guess by a ‘supernatural’ mechanism I mean a mechanism that transcends the laws governing our spatio-temporal universe. i.e. they can’t explain its operation.

RR: So by your criterion, David Lewis’s account of possible worlds is magic? By that definition, what in metaphysics isn’t magic?

SL: See other answers. You’re assuming I suppose if there’s any magic in a book, it’s a magical book. I am allowing philosophy books can include bit of magical thinking. They often do.

Note a book that makes a reasoned case for supposing there’s more than our spatio-temporal universe – as metaphysics sometimes does – is not a ‘magical’ book.

RR: Okay, so the book is not magical if it engages in reasoning, but it nonetheless appeals to the “supernatural” insofar as it appeals to entities/facts beyond our spatio-temporal universe. Is that right?

SL: If Nostradamus includes (perhaps he does?) a few well-reasoned arguments based on his prophecies, it still ain’t a philosophy book. It’s a matter of degree, and overall rational architecture. There needs to be a very significant quota of reasoning.

Postscript

Since our exchange, I’ve had the America song “You Can Do Magic” running through my head on a continuous feedback loop.

The post Philosophy and Magic: What’s the difference? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 8, 2019

Searching for God in Mystical Experience: An interview with Joseph Hinman

Is it possible to encounter God through mystical experience? And if so, is it possible that this experience could provide the rational basis for belief in, and even knowledge of, God? Joseph Hinman has studied this topic extensively and his answer to both questions is yes.

Is it possible to encounter God through mystical experience? And if so, is it possible that this experience could provide the rational basis for belief in, and even knowledge of, God? Joseph Hinman has studied this topic extensively and his answer to both questions is yes.

Mr. Hinman has an MTS from the Perkins School of Theology at Southern Methodist University and has studied at the doctoral level at the University of Texas at Dallas. He has published in the peer-reviewed academic journal Negations: an interdisciplinary journal of social criticism. In his 2015 book The Trace of God: A Rational Warrant for Belief, he makes his case in defense of the rationality of theism based on mystical experience.

I recently had a conversation with Mr. Hinman about mystical experience and the argument of his book. Here is that conversation.

RR: Joe, thanks for joining me for this discussion on your book The Trace of God. Let’s start off with basics. What do you mean when you refer to a trace of God?

JH: To put it in simple terms I was drawing an analogy between the feeling of God’s presence in religious experience and following footprints in the snow. Religious experience is analogous to the footprint of God. I used the term “trace” because the concept of following tracks in the snow reminded me of Derrida’s concept of the trace, which he uses in Writing and Difference and Of Grammatology. I studied Derrida for about four years in my doctoral work. The details of Derrida’s idea of the trace are not important here: the takeaway is the image of tracking footprints in the snow.

RR: Okay, so how does that work, exactly?

JH: What is important is a more complex analogy I draw between the Derridan Trace and Schleiermacher’s concept of the “co-determinate.” The “co-determinate.” is like the notion of a fingerprint or a footprint: it’s the signature that is imprinted by the presence and is always left by the presence of someone or something thing, like a fingerprint. In this case it refers to religious experience. God is leaving his footprint on the life of the believer through the affects (and effects) of religious experience, particularity that known as “mystical experience.” or “Peak experience.”

RR: What kind of experiences are you talking about?

JH: God is not given in sense data, we can’t observe God directly by empirical means, but we can observe the co-determinate empirically through study of the effects of the experience upon the life of the experiencer. At that point the bottom line becomes by what means do we decide that the experiences in question really are the co-determinate of the divine? That is what the arguments seek to clarify, they seek not to prove the existence of God but to provide a means by which we can rationally warrant belief; that is make a valid assumption (which granted is only an assumption) about the experience as co-determinate.

RR: Atheists will predictably claim that specific religious experiences can be explained more simply without invoking the notion of God. To take a simple example, I might say that when I pray I sense God’s peace and love. This experience, so the atheist would say, can simply be explained by the psychological calming impact of prayer which may be no different from an atheist engaging in the practice of meditation. To put it simply, Ockham’s razor slices off the supernatural dimension.

So what kind of experiences are you thinking of which are best explained by invoking the concept of God?

JH: I focus upon what is commonly called “mystical experience” because that particular phenomenon has a huge body of scientific work behind it. Contrary to popular belief Mystical experience is not about seeing visions and hearing voices. Great mystics may have done these things but they are not indicative of mystical experience. There are two major aspects involved in this experience: “the sense of the numinous” and “Undifferentiated unity,” The former is a sense of all pervasive love, a presence of love which many describe as the presence of a person often taken to be God’s presence; the latter is the sense that all things are connected and that differences are illusory.

There is a huge body of scientific study that has been done on this over the last 50 years, starting with Abraham Maslow. This body of work is well known in psychology of religion but is virtually unknown in theology or apologetic. The studies show that religious experiences help you in life, those who have theses experiences tend to score higher on self actualization tests. Studies show that such people are better able to cope with chronic pain, and other such pathological conditions.

These are very misunderstood experiences, They are often written off as the product of mental instability or delusion. Studies show there is no connection between mental illness and mystical experiences, Those who have such experiences more often tend to be more mentally stable, and they have a therapeutic effect that enables those who do have mental problems to recover faster. In my book, The Trace of God, I go into the methodology of these studies in great detail.

RR: Excellent, that’s very helpful. Perhaps we could treat each of these two points in turn, beginning with undifferentiated unity. As you put it, that is the sense that “all things are connected and that differences are illusory.” Here’s my problem: that experience would be consistent with the Advaita Vedanta Hindu school of philosophy. But how does it support western forms of monotheism such as we find in Christian theology?

JH: I have a section in The Trace of God where I discuss Vedanta and the problem of mystical experience in non Christian faiths. Such experience is universal to all religious traditions. The Hindu philosopher Aurobindo was converted to Vedanta as a result of his mystical experience. In fact atheists have them too. These experiences are not salvation, They are perceptions of God’s presence, mystics are free to interpret that as they will, and most of them seek to filter their experiences through the constructs of their own tradition in order to explain their experiences,

The God arguments I made from the data, like most God arguments, are not specific to a tradition. I think the undifferentiated unity is expanded in Christian terms by understanding God’s omnipresence, it is the unity of the life-world of which Schleiermacher wrote. God gives all people the ability to perceive his presence and his everywhere and in all things so we perceive that, but we are free to explain it in any number of ways. In fact universal nature of the experience is the basis for one of the God arguments, there is no basis for a religious gene so the universal nature of God’s presence is an indication that people really are experiencing an objective reality apart from themselves.

RR: Okay, let’s talk a bit about the sense of the numinous. You refer to this experience as an “all pervasive love”. However, when Rudolf Otto discussed the topic in his famous book The Idea of the Holy, he identified two components to this mystery: mysterium tremendum et fascinans. In other words, that mysterious reality is an experience that both attracts as something transcendent and wonderful (fascinans) even as it repels as something terrifying and unknown (tremendum). Would you agree with that analysis? Or do you only analyze the experience in terms of this all-pervasive love?

JH: Yes of course, God is not Santa Claus, he can get pretty serious about things. I felt like that aspect of it requires other things to be in place first before it’s explained. Anything that is immense and transcends the scope of our understanding, the sublime, has that dual aspect, wonderful and terrible. I think when we approach God sincerely and contritely and seek to know go that terrible aspect moves into the background and the loving presence moves into the foreground.

RR: Fair enough. So we can agree that many people have experiences of a numinous reality and/or a sense of undifferentiated unity. And this brings us to the nub of the issue. Why think that these experiences are best explained by positing the existence of God? After all, many atheists and naturalists describe having transcendent, quasi-spiritual experiences when they encounter the universe: Carl Sagan’s Gifford Lectures, published as The Varieties of Scientific Experience, is a great example. Sagan would interpret these spiritual feelings as natural human responses when our own finitude encounters various aspects of nature, such as the unimaginable, majestic scale of the universe.

Why isn’t Sagan right? What requires us to posit God to explain these experiences?

JH: When atheists speak of mystical experiences and say they did not detect God (usually meaning a big man on a throne with magic powers) they are doing the same thing all other mystics do, they are filtering their experiences through an ideological framework that seeks to explain the experience. The studies show the experiences themselves are the same, it’s the explanatory frameworks that differ. When researchers take out the specific references to the various traditions the mystics are all describing the same things.For some, the wonder of nature is a trigger for the experiences but it’s not the only trigger (it has triggered Christian experiences too). For others, it’s classical music, or even theology. They are all having the same experience that leads one to think there is an objective reality out there that is really being experienced. Religious belief is culturally constructed, not a genetic endowment. I discuss these arguments in depth in The Trace of God.

Because it’s not genetic there is no reason why they should be having the same experience. The experiences should not be universal, yet they are. That indicates that there is an independent reality external to the human mind, That is one independent argument for the existence of God based upon the mystical experience research data. A second independent argument is the fact that the vast majority of people who have the experience find that it is about God a priori. They recognize it as a religious experience. That is apart from the need to explicate it by one’s own religious tradition. We know this because it is sometimes a source of conversion; it is also sometimes contrary to one’s own doctrine. Some switched their doctrinal understanding because of the experience, such as Aurobindo, mentioned above.

The third God argument I deal with in the book is called the “Argument from epistemic judgement” (aka “The Thomas Reid argument”). I constructed my own criteria of epistemic judgement by which I feel we habitually use in deciding the validity of experience: it follows the train of thought in Thomas Reid’s “common sense” argument, we accept the validity of experiences that are regular, consistent, and shared (ie inter-subjective). The studies on mystical experience show that these experiences fit this criterion. Therefore, we should trust religious experiences, because they fit the criteria we use anyway. Religious experience arguments have always been assumed to be too subjective to interest philosophers or worry skeptics. Even in the famous radio debate with Bertrand Russell Father Copleston backed off religious experience for this reason, With this vast body of scientific work over the last 50 years, we have empirical backing in the form of 200 plus peer-reviewed Journal studies.

To order The Trace of God: Rational Warrant for Belief, click here.

The post Searching for God in Mystical Experience: An interview with Joseph Hinman appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 7, 2019

What’s So Confusing About Grace? Sale

My book What’s So Confusing About Grace?, a 300-page narrative exploration of the meaning of Christianity and salvation, is available on Kindle for 99 cents! For all you math wizards, that’s an 88% discount!

The deal runs for 48 hrs (8 am PST today until Jan 9) and is available to American purchases at Amazon.com.

Check it out here:

The post What’s So Confusing About Grace? Sale appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 6, 2019

Why I think Christians are morally obliged to make their organs available for donation (posthumously!)

Yesterday, I posted the following survey on Twitter:

Is a person *morally* obliged to make their body available for organ donation unless they have some overriding moral reason not to (e.g. death by highly infectious disease)?

— Tentative Apologist (@RandalRauser) January 5, 2019

In this article, I’d like to narrow the question to Christians.

To begin with, the question is based on the assumptions that (i) one lives in a country where the technology secures the likelihood that great medical benefit to others may come through the donation of one’s organs and (ii) one’s own body is a fitting donor of organs for others.

With that in mind, I offer four simple considerations:

First, Christian theology is predicated on the assumption that our bodies are not, ultimately, our own. Rather, our bodies (and indeed our very lives) are on loan for us to use as long as the divine will allows. Consequently, no question of this type can be circumvented by appealing to the unqualified ownership over one’s body.

Second, Christians are obliged to follow the Golden Rule by divine authority. If one would welcome the provision of a healthy organ from a deceased person if required, then is one not thereby prima facie obliged to make available one’s healthy organs to others when deceased?

Third, Christians are called to love their neighbors as themselves. Posthumous organ donation is a powerful exemplification of this call and, as such, ought to be the normative expectation for Christians.

Fourth, Christians are called to take up their crosses daily. That call involves the expectation of self-abnegation in difficult circumstances, and this final cruciform call should overcome any lingering concerns in the Christian.

Add these points up and, so it seems to me, Christians are obliged to make their organs available for donation posthumously barring some powerful reason not to.

The post Why I think Christians are morally obliged to make their organs available for donation (posthumously!) appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 5, 2019

Van Halen and Christian Joy

It was January 1984, 35 years ago this month, when I first heard Van Halen’s then-new song “Jump” while on a shopping trip at (Canadian drugstore chain) London Drugs. I was mesmerized. And it’s been one of my favorite songs ever since.

A few months later, I was watching the afternoon Canadian rock video show Video Hits on CBC when “Jump” came on. My dad walked in and, after watching David Lee Roth’s frontman antics for a tense 30 seconds, he grumbled: “Punk“.

At the time, I couldn’t explain what I liked so much about the song. It wasn’t simply Eddie’s dazzling guitar and keyboards, Diamond Dave’s sheer attitude, Alex’s irrepressible drums, and Michael’s driving bass. It was something more than the sum of those parts.

It was joy.

What is joy? It isn’t happiness, a fleeting emotion that can change with one’s circumstances. Joy is something deeper, that abiding sense of satisfaction, of wellness, of shalom, that carries one through the difficult times. In the worst of times, it may seem to disappear altogether, but even then it remains as a steel thread of hope. And all the while, joy abides.

Joy is central to the Christian worldview. Indeed, when I wrote an ecclesiology paper for Stanley Grenz 22 years ago, I argued that the unique hallmark of the people of God is this: it is joy. Indeed, his letter to the Philippians, written in the most difficult of circumstances, Paul’s perspective is transformed by joy. And as the letter draws to a close, he shares these words: “Rejoice in the Lord always. I will say it again: Rejoice!” (4:4; cf. 1 Thess. 5:16)

Or in the words of David Lee Roth:

I get up, and nothin’ gets me down

You got it tough, I’ve seen the toughest around

And I know, baby, just how you feel

You got to roll with the punches and get to what’s real

Indeed, we all need to get to what’s real, for therein real joy is found.

This Epiphany, may you find joy in some unexpected places.

The post Van Halen and Christian Joy appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 2, 2019

Christian Post readers reply to my anti-Trump article

Today, Christian Post published my article “If evangelicals are pro-family, then why don’t they care about Trump’s child separation policy?” I expected it to get pushback from the Trumpists and I was certainly right about that. But the vitriol from some folks … wow.

Here I’ll note just one comment. In the article, I pointed out that the Trump administration is violating the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child by separating refugee and immigrant children as young as 9 months old from their parents as a punitive deterrent. Here is how one commenter responded:

“I guess this author [Rauser] feels the same way about all criminals housed in our jails. They should not be separated from their parents either.”

Did you get that? According to this commenter, “Lee Fogarty,” refugee and immigrant children as young as nine months old should be treated like criminals.

That’s a response from (what I presume to be a) Trump supporting “Christian”.

The post Christian Post readers reply to my anti-Trump article appeared first on Randal Rauser.