Randal Rauser's Blog, page 82

March 2, 2019

Why it isn’t helpful to use progressive vs. conservative as boundary markers

Yesterday, I was asked the following question on Twitter:

“as someone who identifies as a [Christian] progressive, how would you define ‘progressive Christianity’ if [I may] ask?”

I thought this question to be worth answering in an article. So here goes.

Let’s begin with a caveat: the reader should set aside any evaluative assumptions. This is especially important with the term “progressive” because the term implies a positive evaluative judgment: i.e. progress. But as I use these terms, they are wholly neutral descriptors. This will become clearer as we proceed.

So let’s get a definition in place: progressive and conservative are terms which apply to individuals who identify with the same community but who have different orientations toward the received tradition of that community. Put simply, the progressive is more likely to revise aspects of the received tradition in light of new data while the conservative is less likely to revise aspects of the received tradition in light of new data.

As you probably know, the terms progressive/conservative are regularly invoked to assert rigid in-group out-group boundaries. However, when properly understood they do not function well as boundary markers given that, as I will now explain, they are relative terms in at least four ways.

To begin with, given that one’s willingness to revised tradition can exist in gradations, it follows that progressive and conservative are orientations on a continuum. Consequently, one may be conservative relative to one person on the continuum but progressive relative to another person. For example, Dave may be a progressive relative to Tony but conservative relative to Ellen.

Second, given that traditions constitute many beliefs and practices, one may be progressive with respect to some aspects of the tradition but conservative relative to other aspects. So imagine that Dave and Ellen are members of the same church, a church that endorses both young-earth creationism and a prohibition of same-sex romantic relationships. However, Dave rejects young-earth creationism while retaining the prohibition on same-sex relationships while Ellen retains young-earth creationism while rejecting the prohibition on same-sex relationships. In this case, it would seem that we cannot place Dave and Ellen on one simple continuum relative to one another. Instead, we must place them on at least two continua. There is no simple and unqualified answer about which one is progressive and which one is conservative.

This brings us to the third relativization. If you’re reading carefully, you may have already picked up on it: progressive/conservative exists only relative to a particular received tradition. Dave and Ellen’s Independent Bible church provides them with one set of received traditions over-against they are defined. But matters are very different for Darryl and Evelyn who attend a liberal Episcopalian Church. Within that tradition, being conservative would involve a strict adherence to the rejection of young-earth creationism and the acceptance of same-sex relationships.

Fourth, we need to recognize that we are not simply talking about traditions simpliciter but rather about nested traditions. For example, Darryl and Evelyn’s liberal Episcopalian church congregation exists within a wider Episcopalian church denominational tradition which may diverge from the particular congregational culture of Darryl and Eveyln’s church. Furthermore, the Episcopalian tradition exists relative to a broader Anglican tradition which exists relative to a broader Christian tradition. So rather than one tradition, we, in fact, have several nested traditions that all exist relative to one another, and categories such as progressive and conservative can obtain at all these levels.

In closing, I’d like to note one more important distinctive, and that is between open and closed communities. An open community is one that welcomes dissent, disagreement, questioning, and exploration of the tradition while a closed community is one that discourages or even censures dissent, disagreement, questioning, and exploration of the tradition. And while it is often assumed that “conservative” communities tend to be closed and “progressive” communities tend to be open, that is not obviously the case. Indeed, in my experience many of the communities that one might think are progressive relative to some particular tradition are, in fact, very closed.

For these reasons, I find it very unhelpful to invoke terms like “conservative” and “progressive” as boundary markers between in-groups and out-groups.

For further reading see my book You’re not as Crazy as I Think, chapter 7 “Not all Liberal Christians are Heretics.”

The post Why it isn’t helpful to use progressive vs. conservative as boundary markers appeared first on Randal Rauser.

March 1, 2019

Anti-intellectualism remains a serious problem in the atheist community

It all started today with a tweet from Jeff Lowder:

With all due respect to @godFreeWorld (who I genuinely respect), I could not disagree more with this tweet. This post-theistic, ostrich (head in sand) strategy makes no sense from an activism perspective and isn't defensible from a probability perspective. 'God' != Santa Claus https://t.co/mKiMTePIJw

— Secular Outpost (@SecularOutpost) March 1, 2019

Now, of course, there are all sorts of nonsense to be found on the internet which is best ignored. But @godFreeWorld is described on his Twitter profile as a “Prof. of Biology” with 26.6K followers, so his opinion is more worthy of note.

I then replied to Jeff:

“Yeah, what a bizarre position to take. Most human beings on earth are theists, including many of the world’s leading intellectuals in diverse fields across the humanities and sciences. You really need to be living in a secular bubble to take this opinion seriously.”

@godFreeWorld then replied to me and I replied in kind:

@godFreeWorld: “Thank you for bolstering my opinion that the endless fascination of philosophy with the bankrupt ‘god’ claim only acts to protect it.”

Randal: “Pure tribalistic anti-intellectualism. Scientists who dismiss philosophy are fools as surely as philosophers who dismiss science. (Fortunately, the latter is comparatively rare.)”

@godFreeWorld: “I have in no way dismissed philosophy. But philosophy does have a failing, and that is its unjustifiable and ongoing fascination with the ‘god’ claim, which is without intellectual merit.”

Randal: “Presumably you recognize that in order to dismiss a field of inquiry one should first be informed on that field. So how well read are you in the field you are dismissing? Do tell…”

@godFreeWorld: “To which ‘field’ do you refer? I have spoken only of the ‘god’ claim.”

Randal: “Let’s start with metaphysics, epistemology, meta-ethics and philosophy of religion, since those are the primary fields in which the concept of God is discussed and debated. Please share your background in these fields that equips you to make your dismissive judgment.”

@godFreeWorld:

Crickets, that’s about the best way to characterize a non-response response, right?

Based on his failure to reply, I must assume that @godFreeWorld has read nothing in the relevant fields of metaphysics, epistemology, meta-ethics and philosophy of religion, and so he is repudiating the topic of God while remaining bracingly ignorant of the fields in which that concept of debated.

This is anti-intellectualism no less egregious than that of the Christian fundamentalist who repudiates biological evolution while having read nothing in the field of evolutionary biology.

The lesson, once again, is that fundamentalist anti-intellectualism is not limited to avowedly “religious” folk. Indeed, in my experience, it remains a pervasive problem among atheists.

The post Anti-intellectualism remains a serious problem in the atheist community appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 28, 2019

An Argument against Islam and Calvinism

I was recently asked by a friend to watch and respond to this short clip in which William Lane Craig offers an argument against God as defined in Islam:

In that clip, Craig appears to present an argument like this:

(1) If God exists, God is the greatest conceivable being.

(2) For any being to be the greatest conceivable being, it must be omnibenevolent (i.e. love all people perfectly and equally).

(3) Allah is not omnibenevolent.

(4) Therefore, Allah is not the greatest conceivable being.

(5) Therefore, Allah is not God.

Interestingly, we can apply that same argument to Calvinism since Calvinism also denies God’s omnibenevolence:

(1) If God exists, God is the greatest conceivable being.

(2) For any being to be the greatest conceivable being, it must be omnibenevolent (i.e. love all people perfectly and equally).

(6) God in Calvinism is not omnibenevolent.

(7) Therefore, God in Calvinism is not the greatest conceivable being.

(8) Therefore, God in Calvinism is not God.

What do you think? Is this a good argument? If it works against Islam, does it work against Calvinism as well?

The post An Argument against Islam and Calvinism appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 27, 2019

Your Child, the Martyr

Tertullian famously said, the blood of the martyrs is seed. Indeed, the early church was built on the witness of early Christians with many giving their lives for their faith. Nor is persecution a thing of the past. Every year, thousands of Christians around the world are persecuted or even martyred for their faith. But Christians are reminded that the very heart of Christianity is the call of each individual to take up our cross and follow Jesus.

So let’s test the ideal of Christian martyrdom in the most painful way imaginable: the lives of our own children. How would you respond to this scenario that I proposed in a Twitter survey?

Christian parents, your child is at high school when a shooting breaks out. The gunman is asking kids if they "believe Jesus is Lord": if they say "yes," they get shot. The shooter walks up to your child and asks if they think Jesus is Lord. How would you want them to answer?

— Tentative Apologist (@RandalRauser) February 27, 2019

The post Your Child, the Martyr appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 26, 2019

Islam and Christianity: A Dialogue

A few weeks ago, I was privileged to moderate an evening of discussion on the similarities and differences between Christianity and Islam at my home church, Greenfield Community Church in Edmonton, AB. The two esteemed guests were Ms. Christa Eisbrenner and Dr. Hassan Masoud. Christa Eisbrenner has an MA in Muslim Studies from Columbia International University and has worked among Arabs in the Middle East and Europe. Hassan Masoud has his PhD in philosophy from the University of Alberta and teaches at several schools in Edmonton. It was a great evening with irenic and engaging dialogue between articulate representatives of two great world religions.

Thanks to Andrew Pohl for filming the event.

The post Islam and Christianity: A Dialogue appeared first on Randal Rauser.

This is Why We Write Books

There is something magical about connecting with a reader. I was reminded of that fact yesterday when, while going through some old files, I came across this handwritten letter from England. It was sent to me back in 2009 by a reader who was entranced by my book Finding God in the Shack.

I treasure every email I receive from a happy reader. But there’s something especially special about a letter, and handwritten, no less! Alas, this gentleman did not include my postal code on the address and as a result, it took about a year for the letter to arrive. But arrive it did. (Kudos to Canada Post.) And when it did, I was reminded again that this is why we write books.

The post This is Why We Write Books appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 24, 2019

Skeptics Shifting Goalposts

Beware of folks who engage in goal-post shifting. This is an informal logical fallacy in which one party shifts the rules for victory after a debate has already begun.

For a great example, we can begin with a tweet I posted this past week:

According to historic Christianity, the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ two thousand years ago in a backwater of the Roman Empire is bringing healing to the entire cosmos, a universe which, at last count, encompasses more than two trillion galaxies.

Wow.

— Tentative Apologist (@RandalRauser) February 19, 2019

Enter Ed Babinski who tweeted a meme in reply:

@SecularOutpost pic.twitter.com/h4nX5ktCgm

— Edward T. Babinski (@edwardtbabinski) February 21, 2019

Ed clearly intends this meme to constitute an objection to my original tweet. We can reconstruct the underlying reasoning as follows: All things being equal, one ought to be skeptical of odd claims: the odder the claim, the more skeptical one should be. The claims of western monotheisms are very odd. Therefore, we ought to be very skeptical of those claims.

For the sake of argument, I set aside obvious problems with the meme. For example, it is no part of Judaism, Christianity, or Islam to assume that God only acts on planet earth. That’s an absurd claim, actually. But as I said, I decided to focus instead upon the main objection, namely that God’s salvific action is uniquely tied to this planet and the human population on it.

Since I don’t find this odd, and I don’t find Ed’s personal incredulity to constitute a good reason for me to reconsider my views, I replied as follows:

“Nope. If you have an argument why they should, please do share.”

So now we have the parameters of debate established. I have described Christian belief, Ed has offered an oddness rebuttal, and I’ve defused that rebuttal by pointing out it is person-relative.

Ed replied like this:

“No, Randal, If YOU have an argument demonstrating that the Bible is inspired cover to cover, please share.”

See how he’s shifting goalposts? He begins by presenting an oddness objection to a specific Christian doctrine about salvation. When I point out that his objection is as meritless as a counterfeit Eagle Scout sash, he then insists that I provide an argument that “the Bible is inspired cover to cover…”

Sadly, I find this kind of behavior to be all-too-common among critics of Christianity. They present a bad argument against Christianity and then, once challenged, insist that I am obliged to present a good argument for Christianity. Of course, I regularly present arguments for Christianity: I’ve written and co-written several books devoted to those topics. But it’s essential to recognize that this new demand is nothing more than an attempt to shift the goalposts from a failed objection.

The post Skeptics Shifting Goalposts appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 23, 2019

Winsome Persuasion: A Review

Tim Muehlhoff and Richard Langer, Winsome Persuasion: Christian Influence in a Post-Christian World. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2017.

Tim Muehlhoff and Richard Langer, Winsome Persuasion: Christian Influence in a Post-Christian World. Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2017.

I’ve been concerned with the art of persuasion for almost as long as I have been interested in apologetics. And there’s a good reason why. As I like to say, you can have the best engine in your car, but if you don’t have the right tires to put that power to the pavement, you’re going nowhere.

So it is with persuasion: you can have great arguments, but if you don’t have the ability to convey those arguments to others in a winsome, accessible fashion, you are going nowhere.

I provided my own account of persuasion in my 2011 book You’re Not As Crazy As I Think, and in the years since, I have continued to read in the area. So when I saw Winsome Persuasion I was immediately interested.

A Quick Overview

Winsome Persuasion is authored by communications professor Tim Muehlhoff and theologian Richard Langer and together they offer a broad-based knowledge of communications, theology, history, and contemporary culture.

The theme of the book is perfectly summarized in the subtitle: “Christian influence in a post-Christian world.” Muehlhoff and Langer are especially concerned with equipping Christians to become an effective “counterpublic”, that is, a minority cultural perspective, which can effectively equip the church to “persuade for Jesus” (Schultze, Foreword, xi). Thus, the focus of Winsome Persuasion is to bring about cultural change at a national level by becoming effective communicators at a local level (25).

To that end, the book is divided into three parts. In part 1: “Laying a Theoretical Foundation”, Muehlhoff and Langer introduce the concept of a counterpublic and the centrality of credibility in being an effective witness. The section is complemented by two extended historical examples that illustrate these skills: St. Patrick’s transformative impact on pagan Irish civilization and Jean Vanier’s L’Arche communities with their equally transformative perspective on disability.

Part 2: “Engaging Others” includes chapters on effectively crafting and delivering one’s message and developing helpful partnerships with those who have a shared interest and perspective on various topics. The analysis in this section is complemented by two extended historical illustrations provided by the extraordinary impact of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin on attitudes toward slavery and William Wilberforce’s tireless campaign to end the slave trade and slavery within the British Empire.

Finally, In Part 3 the authors turn to “Pressing Questions for Christian Counterpublics” to the end of modeling winsome persuasion on a contemporary topic. The topic they select is gay marriage, and the final three chapters of the book are devoted to equipping Christians to become an effective counterpublic on this specific topic.

Yeah, well done

There is much to like about Winsome Persuasion. The authors provide an adept analysis informed by sociological, psychological, theological, and epistemological perspectives. For example, they introduce us to plausibility structures (102 ff.) and their role in weighing live options of belief. And they offer sage advice on the careful balancing of statistics and stories in building a cumulative case for one’s views (114-15).

Speaking of stories, the appeal to narratives is one of the real strengths of the book. The historical illustrations, in particular, are instructive. For example, the authors effectively contrast the strident anti-slavery voices of antebellum America with Stowe’s nuanced approach in Uncle Tom’s Cabin: ultimately, it is the latter which brings about the biggest change in societal attitudes toward slavery. The lesson: prophets have their place, but they can also often polarize and alienate rather than transform.

The authors punctuate their analysis with many shorter illustrations as well. For example, they point to the impressive respect that G.K. Chesterton cultivated with his intellectual opponents to illustrate the importance of credibility, a generosity of spirit, and a measured dose of self-deprecation (75). And Hillary Clinton’s appearance on SNL during the 2016 election illustrates the power of humor to win an audience … just so long as they are not already hostile to you (111). Finally, the Satanic Temple’s ability to defend a shocking statue in public space shows an impressive ability to build a bridge of common understanding:

Strategically, members of the Satanic Temple did not start with their radical belief that Satan is to be admired as an example of those who resist authority. Rather, as a starting point they shared with the press their mission statement, which is, according to Detroit chapter spokesperson Jex Blackmore, to “encourage benevolence and empathy among all people, reject tyrannical authority, advocate practical common sense and justice, and be directed by the human conscience to undertake noble pursuits guided by the individual will.” (101)

With a missed opportunity…

Speaking of the skill at building common understanding, this brings me to the most significant weakness in the book: a relative failure of the authors to inculcate in their readers a nuanced and charitable understanding of dissenting perspectives.

Muehlhoff and Langer are both professors at Biola University, so it is not surprising that the book is written from the perspectives and interests of conservative American evangelicalism. No doubt, those perspectives and interests will be shared by a large portion of the intended audience. But an essential criterion for successful dialogue with others consists of truly understanding the other and presenting opposing views in the strongest light possible (aka steel-manning). And that includes offering critiques of one’s own views from an outsider’s perspective. On this score, the book misses several opportunities to model a nuanced and charitable engagement with the other.

Let’s begin with an example from chapter 1 as Muehlhoff and Langer lament the decline of civil discourse associated with the Trump campaign and the liberal backlash: “inflammatory rhetoric bred inflammatory responses.” (2) Fair enough. However, the authors then raise a topic that will return again in the book: the US Supreme Court decision legalizing gay marriage (Obergefell v. Hodges). To that end, they quote a Buzzfeed op-ed expressing intolerance for the dissenting opinion:

“We firmly believe that for a number of issues, including civil rights, women’s rights, anti-racism, and LGBT equality, there are not two sides.” (Cited in 5, emphasis added by Muehlhoff and Langer).

This opinion prompts Muehlhoff and Langer to reply, “What has happened to our democracy?” (5)

However, is this fair? Does the Buzzfeed sentiment really represent the denigration of democratic engagement? To answer that question, let’s take another look at the first item on the Buzzfeed list: civil rights. This topic was vigorously debated in the Civil Rights era (c. 1954-1968). But it is debated no longer for the simple reason that the public square no longer recognizes segregationist views as defensible and worthy of consideration.

Do Muehlhoff and Langer believe that the democratic public square has suffered, that it has become less democratic, because of the marginalization and ultimate exclusion of racial segregationist views? I assume not. (Keep in mind, we are not talking about censorship per se: free speech remains, even for socially rejected ideas. But that doesn’t change the fact that particular views become stigmatized and thereby widely rejected by the body politic: you have a right to speak, and we have a right to ignore you.)

Assuming that is the case, it would follow that Muehlhoff and Langer agree with Buzzfeed on that point, at least. And so, it turns out that the real question is which views come to be seen as sufficiently problematic, implausible, and/or immoral that they should also be excluded.

Buzzfeed believes that heteronormative views of marriage should be excluded in our age just as racial segregationist views came to be in an earlier age. Muehlhoff and Langer have every right to disagree, but it hardly follows that Buzzfeed is thereby denigrating the public square or eroding democracy. By presenting Buzzfeed’s dissent as an attack on democracy, Muehlhoff and Langer lose an opportunity to model for the reader a charitable and productive understanding of the other, and communication and persuasion are hampered without that fuller understanding.

Here is a second example, drawn from the same chapter. Along with the decline of democracy itself, Muehlhoff and Langer also lament the fact that American culture today is “dismantling sexual morality” (5). While I share their lament over some aspects of changing sexual mores (e.g. the rise of “hook-up culture” (167)), I strongly deny that these changes cumulatively constitute a straightforward “dismantling” of sexual morality.

On the contrary, Christians should welcome many of those changes: consider, for example, double standards on chastity, patriarchal notions of marriage, disregard of domestic physical and sexual violence, the unchecked predatory behavior of powerful elites in business, education, entertainment, and the church, rape culture, and even something as seemingly innocuous as gender exclusive language in academic writing. On all these points, I welcome the change. In short, it ain’t all bad folks, and it certainly ain’t a wholesale dismantling of sexual morality.

No doubt, Muehlhoff and Langer will also agree with many of these changes. But then it is quite unfair to speak of cultural changes as constituting the “dismantling” of sexual morality. Furthermore, it is worth highlighting that the church has been a leader in none of these areas (as the latest debacle in the Southern Baptist Convention makes clear). It turns out that the Leave it to Beaver world was really Pleasantville all along. Once again, Muehlhoff and Langer miss the opportunity to demonstrate effective communication in a more nuanced and charitable engagement with the outgroup.

My final example comes at the end of the book, and it is arguably the biggest disappointment in the book. As I noted above, in Part III Muehlhoff and Langer pursue an extended test case in conversation. The idea is to model fruitful engagement for a Christian counterpublic with a specific topic: the Obergefell decision on gay marriage. The section consists of three chapters: in chapter 8 Muehlhoff offering his analysis, chapter 9 features Langer doing the same, and chapter 10 brings them into dialogue with each other.

Now let me say first that both authors are thoughtful and articulate and they offer some very interesting analysis. For example, there is an extended treatment of the ethics of counseling those in marital situations which deviate from the heteronormative norm. That is a fascinating topic well worthy of further conversation and they both have important insights. Needless to say, these chapters are well worth reading.

Nonetheless, it seems to me that this final section represents yet another missed opportunity to bring the reader into a deeper understanding of positions they (and many of their readers) oppose. While Muehlhoff and Langer do differ on some relatively minor points, they agree on the main point: Obergefell was a mistake. And that delimits the pedagogical value of their exchange out of the gate.

Here is my point: given the importance of understanding the views of others, if Muehlhoff and Langer really want to induct their students into the art of winsome persuasion, they should provide an extended exchange with a person outside their counterpublic. Interestingly, they seem to recognize the general point. One of the authors notes that he has his students read Christian ethicist David Gushee’s book Changing our Mind which advocates for an inclusive pro-gay position. And there is an important logic here, as Muehlhoff and Langer point out: before we evaluate an opposing view, we first need to understand it (95).

I could not agree more. Indeed, that is why I devoted a chapter in my book Is the Atheist My Neighbor? to interviewing atheist Jeff Lowder: if we want to understand atheism and learn how to respond meaningfully to atheists, we need to hear from them. The same is true of others outside our counterpublic. But then, why not invite somebody like Gushee into conversation in the final chapters? Why not offer an articulate spokesperson of the view with which you disagree ample opportunity to share his/her views even as you then model a thoughtful and charitable rebuttal? That, it seems to me, would have been a far more fecund and illuminating way to end the book.

Final Perspective

While I believe Winsome Persuasion misses some important opportunities to challenge the audience and inculcate the skill of steel-manning others, that should not detract from the formidable achievements of the book. While I won’t repeat the virtues noted above, I will point out here that the authors occasionally seek to challenge their conservative readership as in their admirable observation that evolution is compatible with Christianity (103-4). This is old news among many Christians, but it is still a contentious point for many conservative evangelicals, so I appreciate their decision to include the point.

I think it is also worth pointing out just how much better this book is than another recently published evangelical book covering similar ground. While Os Guinness’ book Fool’s Talk yielded significant praise from some quarters, I think it was disappointing borderline terrible. (See my review here.)

Winsome Persuasion is orders better and, in my opinion, is well deserving of its recent award of merit from Christianity Today. But at the end of the day, anybody can type a word of praise. My real appreciation for this book, whatever its faults may be, is that I am adopting it as a textbook in one of my classes. And dear reader, if this book is good enough to be read by my students — and it most definitely is — then that’s all the reason you need to get your own copy.

You can purchase Winsome Persuasion from Amazon (and support this website in the process) here.

The post Winsome Persuasion: A Review appeared first on Randal Rauser.

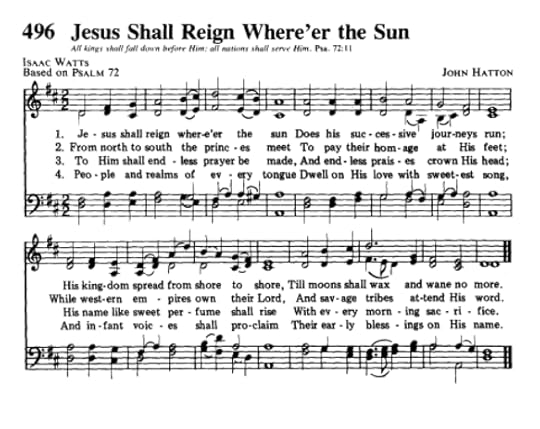

Issac Watts and His Racist Hymn

With over 700 hymns to his credit, including classics like “When I survey the Wondrous Cross,” Isaac Watts is rightly considered one of the great hymn writers of Christian history. Another one of his most well known and best-loved hymns is “Jesus Shall Reign Where’er the Sun”. While I grew up hearing this hymn, I never picked up on the uncomfortable colonial context:

The practice of referring to a great empire as one on which the sun never sets has been around for centuries. But in 1829, Scottish writer John Wilson applied it to the British Empire: “His Majesty’s dominions, on which the sun never sets…” Some years earlier, in 1773, George Macartney had made a similar observation: “this vast empire on which the sun never sets, and whose bounds nature has not yet ascertained.” While the hymn predates these statements (Watts died in 1748), it nonetheless is written against the backdrop of robust British colonial expansion and an easy (and ultimately disastrous) conflation of Colonialism with God’s kingdom. Thus, in the minds of countless choirs and congregants, these verses would be sung with the mental image of the Flag of Great Britain snapping in the wind across the globe.

Bad as that is, today, I learned that it’s significantly worse. Verse 2 has changed, it would seem. While I haven’t researched this, it’s a safe text-critical assumption that “eastern lands” represents an edit of what is presumably the original reading: “savage tribes”.

I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised: Europeans were staggeringly racist moving into the twentieth century. Think, for example, of Kipling’s notorious “White Man’s Burden.” Nonetheless, it is sobering, indeed, to see such baldly racist opinion in a beloved hymn. It also makes one wonder how the songs of today will be viewed in the future. In short, what are our glaring blindspots?

The post Issac Watts and His Racist Hymn appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 20, 2019

The Evidential Burdens of Atheism

Over the years, I’ve met many self-described atheists who insist that they do not need to justify their atheism. They say things like this:

“If you’re going to make a claim about what exists, it needs to be justified.”

By implication, if you make a claim about what does not exist, you are somehow exempted from the evidential burden of needing to justify your claim.

Um, no, it doesn’t work like that. Let’s critique this idea on two points.

First response: the atheist is making a claim about what exists. When a person denies that the universe has a final agent cause of its existence, that person is committing to the existence of a particular kind of universe. And that carries with it many other claims such as, for example, the claim that nature is dysteleological and non-providential. This is a rich battery of claims about what exists. So if the theist’s claims need to be justified in virtue of positive claims about what exists being justified, then the atheist’s claims need to be justified as well.

Second response: claims about what does not exist often need to be justified. Indeed, sometimes existential denials have a special evidential burden. Consider, for example, the claim that minds other than my own do not exist (i.e. solipsism) vs. the claim that minds other than my own do exist. If there is a special onus of justification in this case, it is surely with the former claim: the person who denies that other minds exist needs to justify their claim. One could make the same point about other similar divisions such as the special evidential burden of idealism over-against realism or Humean bundle theory over-against a substance metaphysic of persons.

For these two reasons, the atheist’s attempt to avoid an evidential burden to defend their atheism is doubly flawed.

The post The Evidential Burdens of Atheism appeared first on Randal Rauser.