Randal Rauser's Blog, page 61

March 7, 2020

Be Right Back: On the ethics of using technology to recreate the deceased for the grieving

My wife recently pointed me to this video clip on YouTube — an excerpt from a full-length Korean documentary — which depicts a mother venturing into virtual reality to interact with the beloved daughter that she had lost to leukemia. This is truly an episode of Black Mirror brought to life. It reminds me, in particular, of the Black Mirror episode “Be Right Back”.

The computer programmers fed multiple images of the girl from photographs and videos into a program in order to recreate a 3-D representation. They also recreated her voice (or a very close approximation thereof) with a voice actor. The voice actor also learned the kind of things the child would say so that she could accurately recreate a possible conversation. Next, they placed that 3-D representation in virtual reality and the mother visited her there.

In the clip below, we see the mother first interact with her beloved child in VR. All agree that the mother’s grief is agonizing to witness, but opinions were decidedly mixed on whether this use of technology is healthy for a grieving parent. The mother insisted that it was deeply therapeutic to have this experience, but others worry that this kind of experience is potentially harmful and threatens to prolong the intensity of grief and delay the process of healing. Interestingly, in my view, the Black Mirror episode “Be Right Back” seems to take a middling position between these two extremes.

I haven’t decided what I think about it all. And that means that my article title is somewhat misleading: I don’t have much to say about the ethics of this use of technology. Except, perhaps, this: if this is a beneficial use of technology, one can assume it will remain for some time a prohibitively expensive therapeutic option available only to the well off.

The post Be Right Back: On the ethics of using technology to recreate the deceased for the grieving appeared first on Randal Rauser.

March 5, 2020

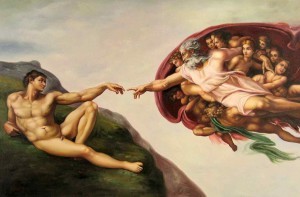

Would it be deceptive if God created a young world with apparent age?

The creation of Adam … at apparently thirty years old.

The nineteenth-century naturalist and conservative Christian Philip Gosse infamously attempted to reconcile the apparent great age of the earth with his reading of Genesis 1 by proposing that God created the universe with apparent age. For example, God created the universe with “annual” layers of arctic ice extending back hundreds of thousands of years and with photons from galaxies millions of light-years distant from earth already in transit.

In short, creation is like a pair of brand new jeans purchased new with tears and worn knees: it looks old and nearly worn out but it is, in fact, fresh from the (cosmic) clothing rack.

Gosse’s apparent age thesis never won much support for one good reason: it is baldly ad hoc. In other words, the apparent age supposition is offered only to explain away the great age of the earth. Thus, there is no independent reason to adopt the thesis.

The apparent age thesis also faces another common objection: it makes God a deceiver. If you buy a new pair of worn jeans knowing that your friends will assume they are old jeans from the back of your closet, then you are guilty of attempting to deceive your friends. Likewise, if God creates the universe in six days a few thousand years ago knowing that the hundreds of thousands of “annual” ice layers and the photons created in transit will be interpreted as signs of great age, then God likewise is a deceiver.

Is that a good objection? Keeping in mind that the ad hoc objection may already provide sufficient reason to reject the apparent age thesis, should we also reject it on the grounds of an intolerable divine deception?

It seems to me that the issue is more complicated than that. Consider, for example, that countless numbers of people throughout history believed that the earth was a flat surface rather than a globe. And it isn’t hard to see why: the earth certainly seems to be flat from the perspective of most folk. Granted, the person watching a tall-masted ship sailing into the distance may notice the hull disappearing before the crow’s nest, but as far as cues of the earth’s sphericity go, that’s pretty subtle. It is hardly surprising that countless perfectly reasonable people concluded that the earth was flat.

And of course, that’s just the tip of the proverbial iceberg. What about the fact that the solid oak desk in your study is composed of vibrating packets of energy in empty space? And you thought it was “solid oak”! Shows how much you know, eh?

And what about the fact that colors are not in the things we perceive but rather are only in our minds? That firetruck isn’t “red”, for example. Rather, the fire truck has the dispositional property that produces a quale in my mind when I see it and I call that experience “red”. But there are no colors, as such, in nature. There are only dispositional properties to produce particular types of subjective experiences in conscious perceivers.

We could go on enumerating such examples of nature misleading us.

Suffice it to say, however, that it would be grossly overreaching to conclude that God was thereby deceiving people by creating the world with the actual characteristics that we have discovered it to have. Mutatis mutandis, it could well be that the universe appears to be old when, in fact, it is not so at all. It hardly follows that God would thereby be deceiving us.

To be sure, it might still be the case that God is deceiving us. That would depend on the divine intent in creating the world as God created it. But we can at least conclude that even if God created a young universe with the appearance of great age, it does not follow that God’s action was thereby deceptive.

The post Would it be deceptive if God created a young world with apparent age? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 29, 2020

If Nobody Else Remembered The Beatles, Would You Think You Were Delusional?

Yesterday, I saw Yesterday, famed British director Danny Boyle’s 2019 romantic fantasy comedy about a fellow who wakes up in a world where he is the only person who knows the music of the Beatles.

Yesterday, I saw Yesterday, famed British director Danny Boyle’s 2019 romantic fantasy comedy about a fellow who wakes up in a world where he is the only person who knows the music of the Beatles.

Yesterday wasn’t the best film I’ve seen this week. That accolade would belong to the 2019 German film System Crasher (aka Systemsprenger) with an honorable mention going to the latest delightful Aardman Animation outing: Farmageddon. (Both System Crasher and Farmageddon are on Netflix.)

Third place is not bad given the stiff competition. And Yesterday has one thing going in its favor (okay, one thing in addition to the great soundtrack and fine acting by all the leads): it got me thinking more than any other film I saw this week.

Thinking how, exactly? Well, two things. First, there is the question of sanity. The film stars Himesh Patel as Jack, the struggling musician who gets hit by a bus during a global blackout after which he is apparently the only person who remembers The Beatles existed. This leads to some humorous abortive Google searches which only turn up results about insects and a hilariously abortive world premiere of “Let it Be.” (An added bit of entertainment is that throughout the film we discover The Beatles are not the only thing that has disappeared.)

Jack initially assumes that everyone is putting him on, but the above-mentioned Google searches followed by the fact that his vast record collection no longer has his cherished Beatles albums shake his foundations. But the interesting thing is that Jack concludes The Beatles have somehow disappeared. He never considers the alternative explanation that they never existed in the first place and that “The Beatles” is nothing more than an elaborate delusion Jack created to account for his own genius.

Of course, the reason Jack never considers this is presumably because the plotting of the film has no interest in exploring the shadowlands between sanity and madness. But it surely is a far simpler hypothesis, especially when we have so many other examples of false memory: e.g. do you remember the Berenstein Bears? Don’t be so sure. Memory can be very tricky.

So about that whole sanity thing. What if I should wake up tomorrow to find nobody had heard of Alvin Plantinga? Would I start making surprisingly novel contributions to debates about the problem of evil and the epistemology of theism? And would I think I were stealing the arguments of a philosopher who once existed — or who exists in another possible world — or would I surmise instead that my arguments came wrapped in a delusion? I am quite certain that at the least I would pause seriously to consider the delusion possibility. How could I not?

This brings me to the second thing. Spoiler alert! Jack eventually decides to let the world know these are not his songs and he retires from his music career. Jack is persuaded by a truly fascinating conversation (that is one spoiler I won’t give up) that this is the ethically right thing to do. But I’m not so sure. There is a minority report in the film which Jack considers but then dismisses, one which says that it is perfectly right for Jack to appropriate The Beatles extraordinary musical catalogue. And I’m not so sure that they’re wrong about that.

So that’s what Yesterday gave me: an opportunity to ruminate about sanity and ethics. Not bad for an otherwise lighthearted romantic comedy.

The post If Nobody Else Remembered The Beatles, Would You Think You Were Delusional? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 27, 2020

A Look at Sam Harris and His Atheist Indoctrination

Sam Harris would be much better off if he read my book.

One of my favorite examples of atheist indoctrination comes from Sam Harris (Letter to a Christian Nation, (2006), 51). He begins:

“Atheism is not a philosophy; it is not even a view of the world; it is simply an admission of the obvious.”

Equating your beliefs with “an admission of the obvious” is indoctrinational in nature because it follows that anybody who disagrees with you is, by definition, denying the obvious. And that is a bald way to secure one’s beliefs beyond critical introspection, a crucial first step in indoctrination.

Next, Harris writes:

“In fact, ‘atheism’ is a term that should not even exist. No one ever needs to identify himself as a ‘non-astrologer’ or a ‘non-alchemist. We do not have words for people who doubt that Elvis is still alive or that aliens have traversed the galaxy only to molest ranchers and their cattle.”

Apparently, Harris is making the profound point that it’s a historical accident that there are people who say “I’m not a theist.” But so what? It’s also a historical accident that people find themselves saying “I’m not a Platonist” or “I’m not a Bernie supporter.” And yet, here we are: Platonism is a major philosophical position and Bernie’s running for president. So if you end up talking with a Platonist or a Bernie Bro, you might well find yourself distinguishing yourself from their position.

But it’s worse than that. Theism isn’t really like Plato’s abstract universals or Bernie’s democratic-socialist political platform. Instead, it is a basic orientation held by the vast majority of people throughout history. To say it is a historical accident that you have to bother saying “I’m not a theist” (or “I’m an atheist”) is akin to saying it’s a historical accident that you have to bother saying “I’m not a moral realist” (or I’m a moral anti-realist”). The vast majority of people throughout history have been moral realists so the fact that you find that odd says more about you than them. It says, in short, that you are living in something of a bubble and you really need to get out and travel more.

Mutatis mutandis for the self-satisfied atheist who believes it to be an accident that he needs to contrast himself from the vast majority of people who have ever lived.

The post A Look at Sam Harris and His Atheist Indoctrination appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 25, 2020

The Top Three Problems with William Lane Craig’s Apologetic

William Lane Craig, PhD, PhD, Rockstar

William Lane Craig is widely considered to be the leading Christian apologist in the world and for good reason. The guy straddles two worlds like few others. On the one hand, he is head of a very influential apologetics parachurch ministry (Reasonable Faith), a fixture at church events and lay apologetics conferences, a podcaster and author of a myriad of popular apologetics books.

And yet, on the other hand, Craig is a very prolific academic with two earned doctorates and more academic books, journal articles and conference papers on his CV than most university philosophy departments. In short, the guy is a rock star.

But that’s not to say there is nothing to criticize. In the past, I have criticized aspects of Craig’s work on several points and in this short article, I recount the top three. And sorry to disappoint some of you, but the kalam cosmological argument is not on the list (although I have complained in the past about the Craig clones — or as Dale Tuggy calls them, “Craigbots”! — who just regurgitate Craig’s kalam argument and his other apologetics without imagination).

And now, the top three problems with Craig’s apologetics.

Number Three: Ultima Facie Beliefs

William Lane Craig sometimes gets criticized for arguing that you can know your Christian beliefs are true without being able to show that they are true. Craig’s critics object that he is being anti-intellectual here. But he’s not: surely if anyone has shown his commitment to reason, it is Craig. Here he is simply making the same point as Alvin Plantinga: we often acquire knowledge in this way.

For example, the vast majority of people gain knowledge through sense perception and rational intuition — two fundamental sources of knowledge — without being able to say how these cognitive faculties work. In fact, many philosophers believe that nobody knows exactly how we gain this kind of knowledge: philosophical theories of sense perception and rational intuition abound but none has won the day. And yet, nobody thinks this, of itself, imperils our knowledge in these areas. And that’s because we can know without being able to show.

Craig makes a similar point about the genesis of Christian belief and since I’ve devoted two books to defending that same view (Theology in Search of Foundations; The Swedish Atheist, the Scuba Diver, and Other Apologetic Rabbit Trails) I’m inclined to agree.

However, Craig also disagrees with Plantinga (and myself) by going further … much further. He claims not only that we can know Christianity is true without showing it; he also claims that the knowledge we acquire here is ultima facie meaning that it has an intrinsic defeater-defeater. In other words, no possible disconfirming evidence can undermine it.

That is wrong, wildly wrong. All our knowledge is defeasible, fallible, corrigible and our Christian beliefs certainly are. I make the point at length in two articles: “Dealing with Doubt? On William Lane Craig’s rather bad advice” and “Beliefs that are forever justified?”

Number Two: Defending the Canaanite Genocide

Some years ago, William Lane Craig challenged Richard Dawkins to a debate. Dawkins declined because, as he argued, he refused to debate anybody who would defend the Canaanite genocide. Everybody (except, maybe, for Dawkin superfans) knew that was a lame dodge. I argued as much in “Why Dawkins’ refusal to debate Craig is not only cowardly, it is immoral.” And the hypocrisy of Dawkins’ indignant moral stand was especially rich given that he has written the following: “The universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is at bottom no design, no purpose, no evil, and no good. Nothing but blind, pitiless indifference.”

But while Dawkins may have had no moral foundation for his ethical indignation, the ethical indignation was itself well justified. When facing the challenge of biblical violence, Craig went all-in on a particular defense, one which I can best describe as a labored spin-doctoring which is only sustainable by a heady dose of self-delusion, moral inconsistency, and cognitive dissonance.

I have written a lot on this topic but if you want to dive in you can start with my thirteen-part (technically, eleven-part plus two) critique of Craig. Check out links at the section titled “On William Lane Craig’s Defense of the Canaanite Genocide“.

Number One: The Existential and Moral Arguments

A centerpiece to Craig’s apologetic is the argument that life is existentially meaningless without God and there is no objective morality without God. When Craig has told his personal testimony about becoming a Christian in high school, he talks about how he reflected on the meaninglessness of existence apart from God and that rumination was a key catalyst in his conversion. And it seems like over the last fifty-plus years Craig has never been able to shake that intuition.

Many of Craig’s listeners share his intuitions. But his arguments in favor of them have been notoriously weak. If you don’t believe me, watch his infamous debate with ethicist Shelly Kagan. Craig is a master debater, but this was arguably his worst performance. And it wasn’t simply because Kagan was himself a surprisingly good debater with an undeniably charming folksy incredulity. It was that Craig’s arguments were shown to be mere emotive talking points based on highly dubious premises.

To sum up, Craig’s legacy in popular apologetics and the academy is secure. But that doesn’t mean he batted a thousand. And these are his three biggest strikeouts.

The next question: who will tell the Craigbots?

The post The Top Three Problems with William Lane Craig’s Apologetic appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 22, 2020

Christopher Hitchens’ Deepity

A few years ago, I wrote an article criticizing Christopher Hitchens’ Razor. This morning, I found myself tweeting about the same topic, and I decided to post my string of tweets here. So now, without further ado, Christopher Hitchens’ Deepity…

One of the best examples of a deepity (i.s. a pseudo-profundity) comes from Christopher Hitchens: “What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.” Many atheists invoke Hitchens’ so-called “razor” as an excuse not to defend their views.

But if Hitchens’ Razor is itself asserted without evidence, it too can be dismissed without evidence.

Even worse, much of what we know with greatest conviction is asserted “without evidence” (i.e. as a properly basic belief). Consider, for example, our basic convictions about the nature of good and evil or rational intuitions like the law of non-contradiction or our belief that there is an external world and minds other than our own. All this is information that we reason *from* rather than *for*.

And if you were asked to defend your belief that evil should be avoided or that it is impossible that p and not-p or that there is indeed a world external to my mind (which includes other minds, too), you’d be hard-pressed to persuade the skeptic because these beliefs are typically asserted without evidence.

But to suggest that one can thereby dismiss basic moral and rational intuitions about the nature of reality simply because everyone else accepts them without argument is absurd. Hitchens’ Razor is nothing more than a deepity, a bit of nonsensical pseudo-profundity.

The post Christopher Hitchens’ Deepity appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 19, 2020

Are transgender women really women?

Are “transgender women” actually women? That depends:

Is “woman” wholly a socially constructed reality that can be fixed by personal beliefs about self-identity reaffirmed by social consensus? If so, then yes.

But if “woman” involves an ineradicable biological element that exists independently of personal beliefs and social consensus, then no.

I believe the terms “man” and “woman” are not merely terms referring to socially constructed gender but also to biologically fixed sex.

So I say no.

We could reduce the heat and increase the light if more folks focused the discussion in this manner. Does “woman” include a fixed biological substrate (whilst recognizing that there can also be social construction) or is it wholly and without remainder socially constructed?

Footnote: even if you do not believe a gender dysphoric man is a woman (or vice versa) you may deem it appropriate to interact with them as if they were a woman (e.g. by using the preferred gender pronouns) based on therapeutic accommodation and hospitality.

The post Are transgender women really women? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

Biblicism Run Amok

Ever wonder what biblicism run amok looks like? For a great example, consider this quote from R. Albert Mohler in his essay in the book Five Views on Biblical Inerrancy (hat tip to my student Rodney for the reference):

“I do not allow any line of evidence from outside the Bible to nullify to the slightest degree the truthfulness of any text in all that the text asserts and claims.”

First, let’s be clear that when Mohler refers to “the truthfulness of any text” what he really means is “my interpretation of the text.”

In other words, Mohler insists that he will not allow any bit of evidence from science to challenge his reading of a biblical text that addresses the age of the earth or the origin of species. He will not allow any bit of experience with powerful women preachers to challenge his complementarian reading of Paul. He will not allow his encounter with monogamous gay couples who appear to have happy, stable relationships to challenge his view of homosexuality. He will not allow moral intuitions to affect how he interprets the moral status of the Canaanite genocide or the draconian punishments (e.g. hand amputation; death by stoning) to be found in the Torah. He will not allow some extra-biblical tradition about sprinkling babies to get him to reconsider his views on believer’s baptism. And on it goes.

The first problem is that Mohler comes to the text as we all do, with a reading tradition that is distinguished by the fact that it rejects what others have claimed to be the truthfulness of the text. Mohler, for example, rejects the notion that biology or geology might affect our understanding of the origin of species or the age of the earth. But he is fine with the fact that science long ago completely led Christians to revise their interpretation of biblical descriptions of the sun moving across the sky and the earth being fixed on its foundations.

Mohler may have no time for women preachers, but he is happy that they have the vote and can own property even though for Christians of an earlier time, the same rationales that restricted women from the pulpit also restricted them from the vote and property ownership (e.g. emotional instability; aptness to be deceived). Mohler hasn’t budged on homosexuality although I’m betting he doesn’t agree with the biblical view of earlier Christians that they should be stoned (admittedly, I could be wrong: I haven’t researched Mohler’s views).

Mohler may be fine with the Canaanite genocide, but I’m guessing that he finds slavery, ethnic cleansing, and genocide in the world today to be morally abhorrent evils to combat. And while he would laud the moral beauty of the Torah, I’m guessing that he would be horrified and morally indignant to read in the newspaper that the Taliban had stoned a recalcitrant youth in rural Afghanistan.

My point is not that Christians should think any particular way about any of these issues. My point, simply, is that nobody does what Mohler claims. For all of us, our reading and application of the words of Scripture are shaped by all sorts of extra-biblical sources: science, experience, moral intuitions, tradition, reason, and so on.

The person who claims that such extra-biblical sources do not affect their reading of the Bible is either fibbing or self-deluded. They are merely posturing to a pious fundamentalist doctrinal confession that they do not, and indeed could not, consistently follow.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is biblicism run amok.

The post Biblicism Run Amok appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 18, 2020

Babies Aren’t Tapeworms and Real Feminists Don’t Revile Fetuses

There are prochoice people who take seriously the moral weight of killing a human fetus and nonetheless side with the right of the mother to do so. And then there are prochoice people who dehumanize and objectify the human fetus, recasting him/her as a “parasite”. This is the same rhetoric used to eradicate populations in genocide, mass killing, and war. It finds its ideological foundation in Judith Jarvis Thomson’s essay “A Defense of Abortion.” And it’s evil.

Yesterday, my daughter sent me this statement she has seen on several prochoice feminist sites. It mocks the moral significance of the human fetus having a heartbeat and being able to feel pain by comparing said fetus to a parasitic tapeworm:

As I said, this is simply wicked. As a rhetorical rejoinder, it is also mind-numbingly stupid. Spitting on the beauty of motherhood and the incomparable gift of a precious, vulnerable new human life in this manner is not pro-woman. It is misogynistic and contemptible.

Here is an extraordinary presentation from TED of the development of a human fetus. If all you see here is a parasitic tapeworm, then I feel sorry for you. For here is a miracle and gift of unparalleled beauty and the very heart of human love.

The post Babies Aren’t Tapeworms and Real Feminists Don’t Revile Fetuses appeared first on Randal Rauser.

February 16, 2020

What do you mean “God can’t”? A response to the Peckham-Oord Debate

Here are some quick evil thoughts pertaining to the most recent episode of Unbelievable featuring a conversation between John Peckham and Thomas Jay Oord. I’m not going to recap their positions here. Just listen to the show and then join the conversation.

First, I didn’t hear enough about John Peckham’s (very Greg Boydian sounding) council of the gods theodicy, but it seems to my untutored ear like he’s taking the remnants of ANE polytheism early in the strata of Judeo-Christian divine accommodation and making it a centerpiece of how God acts in the world and seeks to redress evil. Count me skeptical about this approach. I’d want to hear more — much more — about the nature of this council including (among other things) how it relates to the divine nature. For example, is God Pure Act in which case, isn’t this really that Just So story despite Peckham’s asseverations to the contrary?

But my real concern is with Thomas Jay Oord’s process theology. I admit up front that I’m no fan of process theism and I did not find his presentation of it here to be particularly winsome. Though I’m glad to see that there was no mention of such obscurities as “prehension” and “dipolarity”. But my problem with Oord can best be summarized on a couple of points.

First, Oord’s description of God refraining from intervening in cancer because he loves cells and wants to nurture them leaves me thinking whether we are to view oncologists as less loving than God, given that they go to work burning and cutting cancer out of human bodies. On the contrary, I insist they’re on the side of the angels. The problem, in short, is to figure out how we are to conceive properly of loving human combat with evil when God’s perfect love prevents him from doing the same.

Second, Oord made a big deal of the fact that when people are suffering they are allegedly comforted by the idea that God was powerless to prevent the evil that befell them. No doubt, some folks do think like that. But it is worthwhile keeping in mind that suffering is not necessarily a catalyst for clear thinking. On the contrary, it can often obscure clear thinking, so I would be very careful about drawing any systematic theological lesson from the question of which theodicies are resonant in the midst of suffering.

The more basic point is that it isn’t theodicies which are important when people suffer. Rather, what really matters is other people to love them and walk through the valley of the dark night of the soul with them. Someday we may have a discussion of theodicy in the seminar classroom, but for now, we weep.

Finally, I will say this: if I were in the midst of great suffering, I do not think that I would be comforted by a theology in which God is powerless to stop evil, in which there is no promise that God will wipe every tear from our eyes, in which God doesn’t even know what evils may befall me tomorrow let alone if he will be able to deliver me from them. I am not much for invoking the charge of idolatry at theologies I believe to be errant, but it is difficult to describe Oord’s theology as anything but a paean to the god of egregiously lowered expectations.

The post What do you mean “God can’t”? A response to the Peckham-Oord Debate appeared first on Randal Rauser.