Randal Rauser's Blog, page 65

January 13, 2020

Should Christians engage in boycotts?

This morning, I was interviewed on a Florida radio station regarding my recent article “Screwtaped: On the misguided Christian boycott of Netflix.” I recorded it with my phone. Alas, the sound isn’t great but it’s listenable. (Also note that I edited out a bit where the one host segues to the break along with an extended interlude of traffic, weather, and a Michael W. Smith song.)

As for the interview itself, I had to bite my lip a couple of times. At one point one of the hosts misquoted me: he said “caustic” when I had, in fact, said “casuistic.” But I figured a correction and clarification on such a fine point would not be welcomed and so I kept my yap shut. More troubling was the point where he referred to non-Christian critics as “enemies”. But again, I kept my yap shut for the sake of the bigger conversation.

https://tentativeapologist.s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/Interview.mp3

The post Should Christians engage in boycotts? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 10, 2020

Would you get on the plane?

Yesterday, I posed the following question on Twitter:

You wake up the morning of a scheduled flight from a vivid nightmare that the flight on which you’re booked crashes. You’ve never had a dream that vivid and it is terrifying, but you put it aside and drive to the airport. Once you arrive, you’re walking in the terminal when a woman you’ve never met walks up to you and says, “I’m sorry to bother you but I just feel I have to tell you this: ‘Don’t get on that plane.'” She then hurries away before you can ask her anything. Do you get on your flight?

Jeff Lowder asked about the consequences of missing the flight, an important factor, no doubt. I replied that one can assume the cost is negligible. You can reschedule a flight several hours or perhaps a day later, maybe for a nominal service fee. With that in mind, do you get on the flight or not?

And here are the results:

It would be interesting to plot the responses of people onto a continuum where there are fewer or more data-points than I outlined in the original scenario to see what difference it makes. For example,

Scenario 1: (i) the nightmare.

Scenario 2 (original scenario): (i) the nightmare; (ii) the stranger warning.

Scenario 3: (i) the nightmare; (ii) the stranger warning; (iii) your child also inexplicably begins weeping and pleading “Don’t go” despite the fact that she has never reacted this way before when you’ve gone on trips.

I suspect the significant majority would get on the flight in scenario 1. But as you can see, approximately two-thirds would not get on or are not sure with just one additional factor. I would anticipate a further drop if we added (iii).

This case is interesting for several reasons. First, it makes clear that everyone is apt to identify significant patterns and that we may reasonably act in response to those patterns, even if we are unaware of any cause/explanation of them. And just to be clear, I do indeed believe it would be reasonable not to get on the plane in scenario 2 or 3.

Second, there is a tacit reliance on the kind of decision making pioneered in Pascal’s wager and its seminal contribution to decision theory. In short, one of the reasons it is reasonable not to get on the plane is because the cost of not getting on is negligible whereas the cost of getting on should the plane crash is enormous.

Third, people can rationally form beliefs that an intelligence is at work or a cognitive process (e.g. clairvoyance) even if one has no further information about that cognitive process or how it functions.

Finally, it would be interesting to run the whole test on people with different worldviews: Christians, naturalists, and so on. Because obviously your background set of beliefs will affect your interpretation of this kind of data.

So how about you? Would you get on the plane in scenario 2 or scenario 3? What about scenario 2 or 3 when the stakes were significant (e.g. you were flying to a wedding or a job interview)?

The post Would you get on the plane? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 9, 2020

Being a Theist Does Not Make You Religious

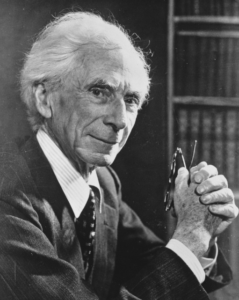

Russell about 60 years after giving up his briefly-held theism.

Time and again in conversation with atheists I find them insisting that theism is an essential component of religion. Indeed, it is not uncommon for them to conflate the two as if theism and religion were straight-up interchangeable.

They are wrong. Flatly wrong. Being a theist and being religious are two very different things and one can be either theistic without being religious or religious without being theistic. I’m going to make the point in two articles beginning in this article as I defend my first claim: being a theist is insufficient to make one religious.

To make my case, we will take a look at a fascinating moment in the journey of arguably the twentieth century’s greatest atheist: Bertrand Russell.

In this excerpt from his Autobiography, Russell discusses a period early in his academic career when he was under the sway of the Hegelian philosopher McTaggart. It was during that period that Russell had a brief but significant change of heart and mind:

“For two or three years, under his influence, I was a Hegelian. I remember the exact moment during my fourth year when I became one. I had gone out to buy a tin of tobacco, and was going back with it along Trinity Lane, when suddenly I threw it up in the air and exclaimed: ‘Great God in boots! – the ontological argument is sound!’” (p. 60)

To call an argument “sound” means two things: first, it is logically valid (i.e. the conclusion follows from the premises); second, the premises are true (and thus, the conclusion is as well). In other words, for this brief period, Russell became a theist and he did so by way of the ontological argument.

Here’s the important part: while Russell became a theist as he was walking along Trinity Lane, he did not thereby become religious. He did not join a community of likeminded belief and practice, he did not adopt any practices at all, he did not worship. He may have been a theist for that time, but his theism was wholly intellectual. In much the same manner that an argument might persuade a philosopher to believe in abstract propositions or sense data or snowdiscalls (yeah, the snowdiscall is seriously a thing of discussion among philosophers!), Russell had come to believe in God. But he didn’t thereby become religious.

And so, the conclusion: being a theist is insufficient for being religious. In the next article, I’ll explain how it also is not necessary.

The post Being a Theist Does Not Make You Religious appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 6, 2020

Why Weak Atheism is Nonsense

So-called weak atheism (or soft atheism) describes the position of a person who does not believe that God exists but who also does not deny that God exists. I’ve raised the following objection to weak atheism before, but I thought it would be worth restating it.

Let’s begin with atheism as conventionally defined. Atheism is the view that God does not exist. And so, the logic of weak atheism is as follows: a person who fails to affirm or deny the truth of a particular state of affairs (e.g. the state of affairs of God’s not existing) can be described as weakly endorsing the position in question (e.g. being an atheist). Thus, the person who fails to believe or deny that God exists can be called a weak atheist.

For the sake of discussion, we can call this the weak principle. And to assume that weak atheism is not engaging in an idiosyncratic and ad hoc use of language, we will charitably assume that the weak principle has general application. Thus, we will assume that it is generally the case that failing to affirm or deny a particular state of affairs is sufficient for one to be described as weakly endorsing the position in question.

With that in mind, let’s return to the position of a person who does not believe that God exists but who also does not deny that God exists. As we have seen, according to the weak principle, this position is sufficient to qualify as a weak atheist. But by the same logic, this is also sufficient to qualify as a weak theist. Thus, every person who is a weak atheist is simultaneously also a weak theist.

And it gets worse. By this logic, the same person who qualifies as a weak communist also qualifies as a weak anti-communist. The same person who qualifies as a weak relativist also qualifies as a weak non-relativist. The same person who qualifies as a weak skeptic also qualifies as a weak non-skeptic. And so it goes.

In other words, the consequences of the weak principle are utter nonsense. And that means that the weak principle is itself nonsense. And that means that weak atheism is also nonsense.

The post Why Weak Atheism is Nonsense appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 5, 2020

On the Hard Sayings of Jesus

Some people worry about the so-called hard sayings of Jesus. But at least keep this in mind: no world-class teacher always says that which is expected, predictable, wholly understandable. There are ocean depths to their words and actions. If they truly are great, we should expect that they will say things which are startling, paradoxical, perhaps even, on their face, offensive. Just as a great novel leaves literary critics debating its meaning and significance for years, so it is with a great teacher. And that’s exactly what we find in Jesus.

And so, while we can and should wrestle with all his hard sayings, we should not, for a moment, be perturbed that he gave some hard sayings. Indeed, that is precisely one of the many things that make him great.

The post On the Hard Sayings of Jesus appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 4, 2020

Is abortion a genocide?

Dear fellow Pro-Lifers,

Please do not refer to support for elective abortion as a “genocide”. The word “genocide” has a specific meaning in international law: it refers to the attempt to destroy an ethnic, religious, or cultural identity. To be sure, genocidaires may use abortion as a means to destroy an ethnic, religious and/or cultural identity. But abortion itself is not genocide.

To put it bluntly, it is irresponsible to attempt to gain a rhetorical advantage in the abortion debate by improperly using (and abusing) the term “genocide”. Doing this merely casts heat rather than light, thereby distorting the nature of the debate and alienating your opponent. This, in turn, merely encourages them to return the favor with incendiary images of coat-hangers and back-alley abortions.

Needless to say, precisely none of this is helpful. So don’t, please don’t say abortion is genocide. It just isn’t.

The post Is abortion a genocide? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

Christian and Atheist Fairyology

Richard Dawkins taking my advice by reading my book “Is the Atheist My Neighbor?”

Many atheists find the study of God to be equivalent to the study of fairies, that is, a misbegotten enquiry into a fantasy reality. These folk seem to take much satisfaction in invoking this equivalence.

But before they take too much satisfaction, they should realize that many Christians view the study of a world without God in the same light: a misbegotten enquiry into a fantasy reality.

I know that many of those atheists will be shocked to learn this because of the bubble in which they live and the feedback loop they enjoy. So let me unpack the Christian perspective briefly. For example, they find it obvious that something doesn’t come from nothing, that every contingent cause ultimately traces back to a necessary cause, that truth-conducive cognitive faculties must ultimately trace back to a knower who designs cognitive faculties to acquire true and not merely adaptive beliefs, that the extraordinarily complex information in DNA could not plausibly be produced through non-directed processes, that the world is enlivened with objective moral obligations which transcend any created being(s), and so on. To seek a world bereft of the necessary agent cause to explain all these things is as misbegotten and fatuous an exercise as hunting fairies in the garden.

So the Christians look foolish, benighted, and intellectually arrested to the atheists. But the atheists look equally foolish, benighted, and intellectually arrested to the Christians. At this point, many folks then retreat behind the high rhetorical walls protecting their in-group and have a good laugh at the misbegotten beliefs and projects of the fariyological outgroup. And so, they live in their bubbles and enjoy their feedback loops.

That response breeds a comforting in-group bond and a smarmy sense of self-superiority. Not surprisingly, that can be addictive and so many people remain within the bubble for a long time, like a fetus that has decided the womb is a far more comfortable environment than the world with all its hard edges and sharp corners.

Needless to say, residing in the fortress, remaining in the bubble, lingering in the womb, all this achieves comfort at the cost of impoverishing one’s own understanding of complex reality and the insights to be offered by one’s neighbor.

For those reasons, I would prefer that both sides set aside the rhetorical jabs and attempts to poison the well and instead treat the other’s different perspective with charity, respect, and genuine interest. And that means knocking down the walls, popping the bubbles, wiggling out of the womb, and for goodness sake, tossing all the well-poisoning nonsense about fairies in the garden.

The post Christian and Atheist Fairyology appeared first on Randal Rauser.

January 3, 2020

Atheism is a Theology

A few days ago, I posted the following statement in a tweet:

“When atheists make claims about God’s non-existence, they are making theological statements. So when they categorically disparage theology — as so many do — they also inadvertently disparage their own theological opinions. That’s called cutting off the branch you’re sitting on.”

The essence of my point is summarized in four words: Atheism is a theology.

Judging by the response that the tweet received, it would seem that many atheists didn’t like hearing that they have a theology. And so I added a footnote:

“I keep getting pushback from atheists who insist that denying God’s existence is not a theological position. That’s like saying ‘There is no such thing as good or evil’ is not a metaethical position or that saying ‘Nobody knows anything’ is not an epistemological position.”

I’m now going to recount a couple of exchanges with atheists who were indignant at being told that they have a theology. The first is a lady named Mareile:

Mareile: Doesn’t theology mean “the study of god”?

Randal: That’s the literal etymology (also “words about God”). A claim that God does not exist (as well as the supplemental evidence provided to support the claim) pertains to that field of discourse.

Mareile: Hard to study something that doesn’t exist, I would think.

Randal: Think carefully: the implication of your statement is that theology doesn’t exist at all. Perhaps you’d like to reformulate your thoughts?

Judging by her response to that last tweet, I don’t think that Mareile grasped the point. Perhaps you missed it as well, so let me unpack it. If one’s response to the point that “God does not exist” is that theological statements cannot exist if God doesn’t exist, then it follows that there is no theology at all if God doesn’t exist. Of course, that’s absurd.

Admittedly, it’s also possible that Mareile was simply making an irrelevant point — a non sequitur. But I was trying to be charitable by assuming that her statement was somehow intended as a rebuttal to the point that “God does not exist” is a theological statement.

Next up, Counter Apologist:

Counter Apologist: Is saying unicorns don’t exist making a unicornology statement? Or is unicornology a field that does not exist if unicorns do not exist? Are there then any (infinite?) number of possible fields of study for entities that don’t exist?

Randal: The only place that “unicornology” is a field is in Richard Dawkins’ imagination… Should we also deny that history, philosophy, and literature are fields of discourse by invoking “unicornology”? Good grief…

Counter Apologist: The point is that making a statement about the existence or non-existence of a thing does not mean that thing has a field of study about it. I could disparage unicornology all I wanted without invalidating the statement that “unicorns don’t exist”.

Randal: Um, I never made the claim that “making a statement about the existence or non-existence of a thing means that thing has a field of study about it.”

Counter Apologist: Ah ok, so it only matters if there is a made up field of study already? So if I demean astrology does that similarly undermine my statements that astrology is false? Or maybe it could be the statement that “astrology is false” could be construed as another kind of statement.

Randal: “so it only matters…” *What* only matters?

Counter Apologist: You said that disparaging theology undermines the statement “god doesn’t exist” because that statement is a theological one.

Randal: So you really don’t understand what I’ve said here? Frankly, your responses are mystifying. Do you not understand that saying “There is no knowledge” is an epistemological statement and that “There is no God” is a *theological* statement?

Counter Apologist: You may construe “there is no god” as a theological statement, but it is also a philosophical or metaphysical statement. One can disparage theology without undermining the statement in a way that is not analogous to saying “there is no knowledge”.

Randal: Yes, it’s a theological, metaphysical, and philosophical statement. (Metaphysics is a field of philosophy and theology and philosophy overlap.) So atheists who disparage theology simpliciter are foolish since, by definition, *they’re in the field*. You really don’t get that?

Counter Apologist: Atheists would say theology is a field studying a fictional entity. The previous tweet I made about astrology is directly analogous. Am I undermining my statement that astrology is false because “astrology is false” is an astrological statement?

Randal: “Astrology is false” means that a particular theory of how planetary orbits affect human beings is false. “Theology is false” doesn’t mean anything since “theology” isn’t a theory. *Theism is*. If you say “Theism is false” *you’re doing theology*.

Counter Apologist: No, the atheist would say they’re doing philosophy; not theology because they’re not studying something that doesn’t exist. As a non-believer in astronomy do my disparagement of astronomers take away from my statements that mercury being in retrograde will not affect my mood?

Randal: Please don’t say “the atheist would say”. That’s what *you* say. Now you’re playing semantic games. When a theist says “If God exists, God is omnipotent” it’s a theological statement but when the atheist says it, it’s a philosophical statement? What about the agnostic?

Counter Apologist: Fairology used to be taken seriously, it *was a field*. If I disparage the field do I undermine my statement that fairies don’t exist because I’m making a fairological statement?

Randal: Oh dear, I didn’t realize you were still stuck in Richard Dawkins’ garden. Disappointing.

Yes, I was sad to see that Counter Apologist ended with a new atheist talking point. But then, I guess I shouldn’t have been surprised since he also began with a new atheist talking point (i.e. unicorns).

So to conclude, yes indeed, atheism is a theology. Theology is not theism, i.e. a particular theory of ultimate reality (as Counter Apologist seemed to think with his misbegotten astrology analogy). Rather, it is a field of inquiry into ultimate reality that welcomes all and sundry: theists, pantheists, agnostics, and atheists.

Well, maybe not all. Ignosticism is a position that this inquiry is nonsensical or hopelessly confused: in short, ignosticism is a vestige of logical positivism, kind of like those folks who still play records (except that records have some redeeming value in the warm tones of the sound, the nostalgic crackle of the needle, and the big album covers and luxuriant liner notes; ignosticism has no such redeeming values).

Oh, and there’s also apatheism, the position that the whole inquiry is not worth pursuing or forming an opinion on. But if an apatheist believes that God doesn’t exist, they still have a theological opinion, even if they believe it isn’t particularly important.

So one more time and in unison: atheism is a theology.

The post Atheism is a Theology appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 27, 2019

Screwtaped: On the Misguided Christian Boycott of Netflix

A few weeks ago, I heard that Netflix has a new comedy show featuring a gay Jesus. So I said, “Yeah, no thanks,” and got on with my day.

Yesterday, I learned that a boycott of Netflix was trending on Twitter spurred on by Christians outraged at that show. So I tweeted:

So now #cancelonetflix is trending because Christians are offended about some stupid show. Do you know how many offensive books and films are in your public library? Should we cut up our library cards? Please Christians, grow a thicker skin.

— Tentative Apologist (@RandalRauser) December 27, 2019

In this article, I’m going to enumerate three problems with these misguided boycotts and protests.

Let’s start here. After posting the tweet, one fellow then asked me: “Which movie?” And you may very well be wondering the same thing: Yeah, which movie is that, anyway? Which is, of course, the first problem: all these outraged boycotts do is drum up interest in the offending product thereby granting it loads of free publicity. Back in 1988, the mediocre film The Last Temptation of Christ would have quickly sunk into obscurity if Christians hadn’t made a point of picketing theaters.

So that’s the first problem: boycotts/protests give free publicity to the offending product.

But it’s worse than that. Another fellow asked me on Twitter, “Dude, what are you an apologist for again?” Someone else then interjected, “At least in this case, not being a whiny baby.” Exactly. I’m an apologist for Christians not being whiners who invite the derision and contempt of a wider pluralist society. Apologists should be concerned with presenting a winsome, welcoming Christianity, not one that is known for its protests and boycotts. And yet, the reality is that Christians often are known more for what they’re against — same-sex marriage, abortion, gay Jesus comedy shows on Netflix — than what they’re for. You can have great arguments for the existence of God and the resurrection of Jesus, but if people write you off as a censorious curmudgeon worthy of derision, you won’t even get an audience to present those arguments.

So that’s the second problem: boycotts/protests hurt Christian witness.

Finally, let’s turn back to my tweet for a moment. As I pointed out, if you believe in boycotting Netflix for making content you deem offensive available to others, why don’t you boycott your public library, too? And why not also boycott the local bookstore and YouTube and Facebook? Where does this stop? Perhaps you should move to the mountains and build yourself a log cabin off the grid so your eyes and ears need be sullied no more by the things of this world!

Others will say, “Ah, our protest is not simply that Netflix made this content available, but also that they produced it!” Okay, so now the protest is focused in on the production of the offending content. In that case, do you believe in protesting every studio that produces content you find offensive? Once again, where does that stop?

Furthermore, if the producers are worthy of boycott and protest, why aren’t the distributors equally worthy of boycott and protest? You wouldn’t target the producers of child pornography and leave the distributors untouched. So why doesn’t the same logic apply here? In short, if you’re going to boycott the studio, you should also boycott the public library, the local bookstore, YouTube, Facebook, and all other modes of distribution. And in that case, the boycott just got much larger.

So that’s the third problem: consistently following out the logic of knee-jerk boycotts/protests like this sets Christians up to be either wing-nuts living in log cabins off the grid … or casuistic hypocrites who confabulate tortured justifications to explain why they’re boycotting ‘ x’ but not ‘y’.

What do we do?! How can we proceed?!

Fortunately, there is another way through this morass. You could just say, “A new comedy show featuring a gay Jesus? Yeah, no thanks.”

The post Screwtaped: On the Misguided Christian Boycott of Netflix appeared first on Randal Rauser.

December 24, 2019

If We Make it Through the Most Wonderful Time of the Year

For many people, Christmas is “The most wonderful time of the year.” Andy Williams captures the spirit perfectly in his perennial 1963 Christmas classic:

For many people, Christmas is “The most wonderful time of the year.” Andy Williams captures the spirit perfectly in his perennial 1963 Christmas classic:

It’s the hap-happiest season of all

With those holiday greetings and gay happy meetings

When friends come to call

It’s the hap-happiest season of all

But for others, this holiday season is better captured by Merle Haggard’s song “If We Make it Through December,” a melancholy lament that topped the charts for more than a month in 1973-4. It would seem that many resonate with the spirit of Haggard’s sad words:

Got laid off down at the factory

And their timing’s not the greatest in the world

Heaven knows I been working hard

Wanted Christmas to be right for daddy’s girl

I don’t mean to hate December

It’s meant to be the happy time of year

And my little girl don’t understand

Why daddy can’t afford no Christmas here

So here are my thoughts. If you find this to be the most wonderful time of the year, say a prayer or save a kind word for those who are just trying to get through the month. And if you’re just trying to get through the month, remember that a new year brings with it the hope and promise of better days.

Above all, be well, and Merry Christmas.

The post If We Make it Through the Most Wonderful Time of the Year appeared first on Randal Rauser.