Randal Rauser's Blog, page 59

April 11, 2020

Is the misery of hell self-imposed?

C.S. Lewis famously said the gates of hell are locked on the inside, and many people think this idea that the misery and suffering of hell are self-imposed somehow lessens the moral problems with the doctrine. But does it?

In this fantastic video with atrocious production values, I suggest otherwise.

The post Is the misery of hell self-imposed? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 10, 2020

Dry Your Tears with Love: The Saddest Song for Good Friday

In 1994, I spent a summer teaching English in Japan. It was at that time that I first became acquainted with the massively popular Japanese visual kei metal band X (aka X Japan). The best way to describe visual kei is that it is a Japanese adaptation of glam metal with a uniquely Japanese aesthetic such as the use of kabuki style in the use of makeup. X Japan are classically trained musicians and the heart of the band is Yoshiki, an extremely influential and revered musician, songwriter, and producer.

In the 1990s, X Japan became especially renowned for their sprawling ballads, and arguably the best is their 1993 hit “Tears.” The song was written by Yoshiki who also plays the piano in the performance. It tells the story of how, when he was ten years old, he lost his father to suicide and it conveys the indescribable grief and sense of loss of a child. “Tears” is the saddest song I know. That makes it perfect for Good Friday.

The post Dry Your Tears with Love: The Saddest Song for Good Friday appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 9, 2020

Inspired Imperfection: A Review

Gregory A. Boyd. Inspired Imperfection: How the Bible’s Problems Enhance Its Authority (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2020).

Gregory A. Boyd. Inspired Imperfection: How the Bible’s Problems Enhance Its Authority (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2020).

The postscript to Gregory Boyd’s new book Inspired Imperfection tells the story of a woman whose beloved vase was broken into several pieces. Devastated, she initially sought a restorer who might bring the ceramic back to its original, pristine condition. However, even the most precise restoration would likely leave discernable, hairline cracks in the finish.

Then she discovered a practitioner of kintsugi, a Japanese craft that reassembles broken pottery by way of a bright gold lacquer which highlights rather than diminishing or erasing the cracks. The result was a vase that was better than the original, not despite but rather because of the “beautiful scars” laced in gold. (Me being a car guy rather than a pottery guy, I couldn’t help but think of another analogy: the practice of incorporating a rust patina rather than a glossy repaint into a meticulously restored automobile.)

It’s a brilliant metaphor that eloquently captures the central thesis of Inspired Imperfection. Boyd recounts that it was in university more than forty years ago that he first encountered the ugly cracks in the Bible, cracks such as content that was scientifically problematic, internally contradictory, or straight-up immoral. This discovery shattered Boyd’s inerrantist understanding of Scripture and for several years he wrestled with ways to put the text back together in a way that would erase those ugly scars. But eventually, he came to realize that there could be no meticulous reassembly: “it began to feel to me like we were trying to move Mount Everest with a tablespoon.” (42)

An example of Kintsugi (but you probably figured that out).

It is at that point that many Christians have found themselves losing their faith altogether. But not Boyd. In a paradigm shift to a theological version of kintsugi, he became convinced that the problem lay with the perception that the cracks in the text were problems to be erased: instead, he determined that they should be laced with gold. Boyd also came to believe that Jesus has the Midas touch: in other words, Boyd’s restoration of the text was christologically framed.

Many other theologians have also proposed a christological way to deal with the cracks, though typically it is by way of an incarnational model: i.e. Scripture evinces both full divinity and full humanity (Peter Enns provides one of the best examples).

Incarnational models can address some problems: for example, understanding the degree to which God accommodated to human limitations in the kenosis of the incarnation could inform how God accommodated to human limitations in inspiration. To note one example, Boyd insists that we are misguided to be worried about whether Jesus really believed that Moses authored the Pentateuch: “The historical-critical debate over the various sources that comprise the Pentateuch would have been as far from Jesus’s mind as the nagging contemporary question of how to reconcile general relativity theory with quantum theory.” (67)

While incarnational models are adept at addressing human limitations in the text, they also have a rather glaring weakness. While Jesus was fully human, he was not a fallen human and thus his limited human cognitive awareness never evinced imprudence, let alone sin. By contrast, the text of Scripture does include actions/commands that are imprudent if not evil such as the horrific punishments in the Torah (stoning; burning; limb amputation), divinely commanded genocidal wars, and a collection of psalms replete with repeated curses of and hatred for one’s enemies. So at that critical point, the incarnational model breaks down (86).

Boyd thus shifts his focus from a model of Scripture based on the Word made flesh to one based on the crucified God:

“This model of inspiration stipulates that, when understood in light of the cross, the Bible’s problems are no more problematic to it being considered the God-breathed story of God than the sin and curse that Jesus bore on the cross are problematic to it being considered the God-breathed definitive revelation of God.” (152)

Boyd has a few key interlocutors in the book. Karl Barth gets the most attention as the theologian who helped Boyd cut the Gordian knot by shifting the locus of revelation from the Bible proper to Jesus Christ, the one to whom the Bible witnesses. Barth also helped Boyd come to terms with the fact that “imperfections” in the text could be part of divine inspiration.

However, Boyd has since moved beyond Barth and he offers some well-articulated criticisms of Barth’s Neo-Orthodox account of Scripture by insisting on the importance of retaining a commitment to plenary inspiration: in short, the text itself is objectively revelation and not only the medium of it (70). (Boyd’s concern to defend the historicity of the main details of the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus also contrasts with Barth’s rather sharp contrast between historisch and geschichte (cf. 62).)

Though Jurgen Moltmann does not get the same attention as Barth, he is even more central to Boyd’s crucifixion model in which the apogee of divine revelation comes through Christ crucified (92). As Boyd says,

“we wouldn’t say that the cross fully reveals God in spite of the humanity, the sin, and the God-forsaken cruse that Jesus bore. To the contrary, the cross fully reveals God precisely because it reveals a God who, out of unfathomable love, was willing to stoop to an unsurpassable distance to enter into solidarity with our humanity, our sin, and our God-forsaken curse.” (95)

Nerdy theological aside: It is important to understand that when Moltmann burst on the theological scene in the early 1960s, he was known, along with his fellow German Wolfhart Pannenberg, as a theologian who elevated the centrality of history as a means of divine revelation. God is known supremely through his actions in time. This involves a shift from Barth’s focus on the person of Jesus simpliciter as the locus of revelation to the person of Jesus as revealed in the events of his life, death, and resurrection. Moltmann views events as the locus of revelation, and the event of the crucifixion is supreme among them.

When Boyd made the shift from Barth to Moltmann, he made the shift from viewing Scripture on an incarnational model (the person of Jesus) to an event model: the person of Jesus as he is crucified. And that offers the critical opportunity to include not only human limitation in the biblical text, but also the evil and imprudent actions of fallen human actors within the event of the crucifixion itself. In this way, Boyd avers that the central event of crucifixion provides a powerful revelation of the crucified God in the midst of human brokenness and evil, so Scripture as primary witness to that God also shows the crucified God in the midst of human brokenness and evil.

Needless to say, some critics will find this to be an ad hoc rationalization meant to defend a text that is, at points, indefensible. So it is important to appreciate how much effort Boyd exerts in defending the claim that this view of Scripture is, in fact, a natural and expected implication of a radical conception of revelation as finding its apogee in the crucifixion of God on a cross. Everything changes when you view Scripture through the lens of the crucified God.

Reflections

So what do I think of Inspired Imperfection? Before I get started, let it be noted that this is a popularization of Boyd’s massive two-volume The Crucifixion of the Warrior God. I haven’t yet read the longer work, but Boyd is to be lauded for taking his ivory tower musings and both condensing and simplifying them for a popular audience. And with that, keep in mind that my criticisms of Boyd’s argument may well be addressed in that longer work. That said, Inspired Imperfection is the book I have and it is the book I’m reviewing. So let me begin by listing some points where I disagree with Boyd. Next, I’ll list some points where I would differ from Boyd. And finally, I’ll draw my overall conclusions about the book.

First up, I’ll list some of my points of disagreement.

Boyd criticizes Barth as a fideist: “Barth is essentially arguing that the only proof that the Bible is the inspired story of God that believers need is the fact that they believe the Bible is the inspired story of God.” (74) I think it is quite unfair to charge that kind of vicious circularity to Barth. First, a sympathetic interpretation should always keep in mind that his strident position was forged as a prophetic response to National Socialism and Barth’s understandable fear that any concession to natural theology would weaken the church’s radical prophetic stance to this demonic movement. Second, rather than read Barth as viciously circular, one can (and I think should) read him as offering a postfoundationalist position which disavows the search for external evidences to justify one’s Christian commitment.

I was unclear as to how Boyd believes the Holy Spirit works with the human authors. But I think his dismissal of a divine appropriation approach (59) such as one finds in the work of Nicholas Wolterstorff and William Lane Craig was too quick.

Boyd has an erroneous view that God’s revealing truth directly to a person overrides their free will. He writes that God “works by means of the power of the cross, which is the influential power of other-oriented love, rather than relying on coercive power to lobotomize God’s people into having true thoughts about God.” (148) I’m sorry, but this is bizarre: if I tell you something that is true with the end of you forming a belief that it is true, I have not destroyed part of your brain. The underlying idea behind Boyd’s comment here seems to be that human beings have volitional control over our beliefs, a view sometimes called doxastic voluntarism. But this is clearly false. I make choices about how to reason and which evidence to consider, but I don’t choose the resulting beliefs: rather, I find myself with them.

Next, I’ll list some points of how my treatment of the issue would differ from Boyd’s.

I affirm an appropriation model of divine inspiration (though one that allows for additional special intervention of the Holy Spirit in particular cases: cf 2 Peter 1:21). Boyd could not endorse the same view because it depends on divine middle knowledge and foreknowledge of free human actions and as an open theist, Boyd denies that God has such knowledge.

I focus on the analogy of God as divine editor, appropriating the human texts of his people (Israel, the church) into a divinely authorized text which testifies to Jesus Christ so that we may be formed into his image.

As a result, I am willing to retain the language of inerrancy that Boyd repudiates, though I make the critical shift of locating the property of inerrancy not in human authorial intent but rather in divine authorial intent. (If you want a quick analogy, some literary critics have proposed editions of James Joyce’s Ulysses that correct typographical errors in the text. Others retort that Joyce’s typographical errors in the text are part of the author’s intentions and should not be “corrected” by the red pen of overly-eager critics. Read about the debate here.)

I would place a greater emphasis on the central importance of the freedom to wrestle with and interrogate the text as being part of the formational power of the text to form God’s people as they who strive with God (Genesis 32:28).

And Now, the Conclusion

I could go on for awhile enumerating other examples where I disagree with Boyd or would do things rather differently. But to do so would be to abuse my role as a reviewer of the book Boyd wrote by instead talking about the book I think I should write.

It would also convey the wrong impression that I am unhappy with the book Boyd did write. Quite the opposite, in fact: it’s a very stimulating little book and my desire to engage it critically is a sign of its effectiveness. When I read Inspired Imperfection I find that I am reading a kindred spirit. Boyd has wrestled with the text in the manner that I believe should exemplify the raw honesty and boldness of God’s people (cf. Genesis 18:16-33). In Inspired Imperfection he offers a way to face Christian cognitive dissonance about the Bible head-on by viewing it through the cross. In that way, we may begin to see that the cracks of this shattered pot are in fact laced in gold.

Thanks to Fortress Press for a review copy of this book. You can order your own copy of Inspired Imperfection here.

The post Inspired Imperfection: A Review appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 7, 2020

Are Christians Inconsistent for Rejecting Non-Christian Miracle Claims?

In my article, “Responding to a Stale Atheist Talking Point on Miracle Claims,” I … respond to a stale atheist talking point on miracle claims. But since the article is a relatively brief amalgam of some tweets, it lacks in clarity what it makes up in brevity. However, I thought a second article that surrendered brevity in favor of clarity would be wise. And in case you haven’t surmised by now … this is that article.

Imagine that you were to encounter a person who rejects the principle of testimony, i.e. the principle that we can have properly basic belief based only on a person’s testimony. They ask you,

“Okay, smart guy, if you’re going to believe testimony at face value, what keeps you from accepting just anybody’s testimony? Like, why don’t you accept the testimony that an alien landed on your roof?”

You’d reply:

“I judge testimony based on what I believe about the world. It’s called a ‘plausibility structure’ and it provides a prima facie means to sort the plausibility of various testimonial claims. To be sure, it is indeed only prima facie and can be challenged by good evidence. I don’t think that aliens exist, but my brother-in-law does. So I would be skeptical of that testimonial claim unless evidence was provided. I wouldn’t take it at ‘face value.’ But he’d likely be more open to it. And so, if he found the testifier to be especially credible, he might believe it without further evidence.

“And so, there is nothing inconsistent with accepting some testimonial claims at face value and rejecting others. We make such judgments relative to our background beliefs. And from our respective frameworks, each of us then assesses the claim.”

Now switch out “testimony skeptic” with “miracle skeptic.” The exact same response applies. There is nothing inconsistent with granting prima facie credibility to one subset of miracle claims based on one’s background set of beliefs. Nor is this invoking a special exception. Rather, it is precisely the same norm that is applied across the board when we evaluate truth claims, including testimony. As a Christian, I’m prima facie skeptical of Sathya Sai Baba’s miracles for the precise same general reason that Counter Apologist is skeptical, i.e. because those claims are inconsistent with other things I believe about the world. To be sure, the precise set of specific reasons that I will be skeptical will differ to some degree from that of Counter Apologist. But nonetheless, we will both be skeptical of the Sathya Sai Baba miracles for the same general reason: inconsistency with our current beliefs about the nature of reality.

To conclude, it should be underscored that since my skepticism is prima facie, if you provide powerful evidence for those miracle claims or other anomalous or extraordinary claims, then I’ll consider it. Case in point, in this article I note why I take Ian Stevenson’s evidence for reincarnation seriously even though I’m not ultimately persuaded by it. And also read my article “On taking an objective approach to inexplicable events.” And for kicks and giggles, you might also read my article “What a coincidence! An exercise in worldview analysis.”

The post Are Christians Inconsistent for Rejecting Non-Christian Miracle Claims? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 6, 2020

Responding to a Stale Atheist Talking Point on Miracle Claims

In this post, I’m recounting a bit of an exchange I had on Twitter with Counter Apologist followed by my reply:

Oh I've got my background beliefs but my point is that miracles claims made by multiple living eye witnesses of Sathya Sai Baba are rejected by Xtians yet 2nd and Nth number hand claims in the gospels are held up as clearly plausible. It's not so in India https://t.co/6k6QiUFX6Y

— Counter Apologist (@CounterApologis) April 6, 2020

I offered the following multi-tweet response which I’ve recorded below:

It never fails: an atheist skeptic of miracles will reason if you accept Christian miracles, you have no principled reason to reject “Sathya Sai Baba” talking point. I’m sorry, but this is not serious. It’s just an atheist talking point.

Let me give you an analogy. Most people believe that you can gain rational belief and knowledge directly through human testimony. But others are skeptics of human testimony. They don’t believe that is possible. Now imagine a skeptic of human testimony saying this:

“If you’re going to accept Smith’s testimony that another motorist dented your car, why don’t you accept Jones’ testimony that an alien landed on your house?”

I mean, what a silly bit of reasoning that would be. People have many ways to distinguish credible testimonies.

And people have many ways to judge credible miracle claims. Wright, Licona, and Habermas all do a fine job making the case for the resurrection of Jesus. I’ll wait for Counter Apologist to make the case for Sathya Sai Baba.

The post Responding to a Stale Atheist Talking Point on Miracle Claims appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 5, 2020

Friend of Science, Friend of Faith: A Review

Gregg Davidson, Friend of Science, Friend of Faith: Listening to God in His Works and Word. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Academic, 2019.

Gregg Davidson, Friend of Science, Friend of Faith: Listening to God in His Works and Word. Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel Academic, 2019.

The year was 1988 when I brought my dog-eared copy of Paul Ackerman’s It’s a Young World After All to my high school science teacher: “Mr. Vogt, you need to read this! It will prove that the earth is young!”

Yes, back in those days, I was a strong young earth creationist. As a case in point, my many fierce debates with my buddies about the age of the earth and the “atheist philosophy” that I insisted drove belief in evolution. My favorite Christian singer, Larry Norman, captured my sentiments perfectly with his clarion call: “Ain’t gonna let no evolutionist make a monkey out of me!”

Had Gregg Davidson’s Friend of Science, Friend of Faith been available to my high school self, it would’ve rocked my world. Davidson’s book has two objectives. To begin with, he proposes a helpful method to resolve apparent conflicts between science and Scripture by using scientific advances and insights as critical prompts to reread the text: “new insights may simply serve to dust away never-intended meanings that cloud our view, allowing the true message, one that was there all along, to shine more brightly.” (18) Second, he seeks to apply that method to the debate over origins.

The Case Against Young Earth Creationism

The critical application is the primary focus of the book. While Davidson devotes a chapter to discuss the origin of the universe, the primary focus is on young earth creationism (henceforth YEC) and the related questions of geology and biological origins. This is in keeping with Davidson’s own specialty in earth science as the Chair of Geology and Geological Engineering at the University of Mississippi. But while Davidson is a scientist, what gives this book the real added value is that he also has intimate knowledge of the theological, hermeneutical, scientific, and rhetorical methods common within YEC and he is at his best when he is providing an even-handed deconstruction of them.

Consider, for example, how in chapter three Davidson takes on the YEC assumptions about reading the “plain sense” of Scripture (39 ff.). In fact, time and again the plain sense of the text supports an ancient understanding of a flat earth resting on pillars with an ocean held above the earth by a hard dome. The proper response, as Davidson proposes, is that God accommodated to the understanding of an Ancient-Near-Eastern (ANE) worldview as the incidental vessel for his revelation. Nothing too surprising here. But then Davidson gives a point-by-point rebuttal to YEC attempts to deny accommodation in the text (43 ff.). For example, YEC advocates sometimes claim that the language (e.g. of the sun rising) should be interpreted as a figure of speech. However, it is absurd to claim that the Israelites meant this language figuratively when their ANE neighbors clearly meant it literally (44). In this way, Davidson demonstrates the tortured ad hoc nature of YEC reasoning.

Davidson has a memorable way of unmasking problems with flat-footed literalistic readings of the biblical text. Consider, for example, how he explains the difficulties with a plain reading of the separation of light from darkness in Genesis 1:

“consider a jar of beans set before you. They are poured out onto the table and you are given a simple instruction: separate beans from the absence of beans. You object, ‘That has no meaning; the absence of something is not an independent “something”!’ Which is exactly the point. Something wonderful is expressed when God separates light from darkness, something much deeper than what a nonsensical ‘plain sense’ reading would imply.” (62)

I mentioned above that Davidson addresses not only the theology and science of YEC but also their rhetorical strategies. And that brings us to one of the most satisfying and eminently practical chapters: chapter 11, “Creation Science–Behind the Curtain.” One after another, Davidson knocks down YEC strawmen. For example, he points out that YEC falsely suggests that uniformitarianism dogmatically commits one to the gradual formation of geological features over eons. But that is false: uniformitarianism simply commits one to the same geological processes and forces operative today having operated in the past and that is consistent with catastrophic geological events also occurring in the past (210). And then there is the “Evolution is only a theory” canard (210-11) and the misbegotten notion that “the second law of thermodynamics makes evolution impossible” (212-14). One after another, Davidson shoots down these erroneous talking points like a trained marksman. The message comes through loud and clear: “Young-earth arguments far too often serve as a barrier rather than a gateway to faith in Christ.” (206)

Three Points of Critique

I’m on board one hundred percent when Davidson is critiquing YEC. However, I do have some points of criticism and here I will list the top three: concordism, intelligent design, and the unaddressed topic of divine action.

For the purposes of this review, I will define concordism as “A system of exegesis aimed at establishing a concordance between biblical texts and scientific data.” (source) YEC is classic concordism as it seeks to correlate various biblical assertions (e.g. “Let there be light”) with specific scientific claims (e.g. the Big Bang).

With that in mind, it is somewhat ironic to accuse Davidson of also falling under the concordist spell, but such as it is. This does seem to me to be the case, especially when he addresses various passages in Genesis 1-11. My first example pertains to that curious passage in Genesis 6 where we read that the “daughters of men” engaged in sexual relations with the “sons of God”, thereby producing hybrid creatures known as the Nephilim. A curious text fitting as a mythic narrative told around the campfire: but Davidson proposes that it could be, in fact, describing interbreeding that occurred between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals and Denisovans (91).

I admit that Davidson’s proposal is an interesting one. But when I set aside the YEC hermeneutical baggage I see in Genesis 1-11 a collection of etiological myths that God appropriated into his divine text. (In this context, “myth” does not mean falsehood but rather a structuring story with universal import because it conveys something about the nature of the world in narrative form.) It seems to me just misguided to attempt to correlate these narratives with scientific data points in earth history.

While there may be a superficial plausibility to concordist theses like Davidson proposes, I think that plausibility disappears upon closer examination. While I’m no scientist, as I understand it, according to current estimates, the Neanderthals died out approximately 40,000 years ago, which would be more than 30,000 years before the first human writing system. From my view, it strains credulity to think the claim that the event of Homo sapiens interbreeding with Neanderthals and/or Denisovians was either maintained in an oral tradition for tens of thousands of years or that it was supernaturally revealed under the aegis of the curious Genesis 6 narrative that we have.

Concordism also appears to be in the background of Davidson’s treatment of the Noahic flood. Once again, his proposal is interesting if not ingenious. Davidson proposes interpreting the Noahic flood by way of the Mediterranean flooding the Black Sea region, an actual event in earth history. This is how he describes it:

“Torrential rains begin to fall at the same time that water begins to pour into the Black Sea from the Mediterranean. The ark, built on the shores of the sea, soon begins to rise. The ark drifts far into the sea during the rain. For months after the rain, land is too far beyond the horizon to be visible. No evidence of animal life can be found, and even fish have died from the rapid introduction of salt water from the Mediterranean. All flesh as far as the eye can see dies. As Noah relates the story to his children and grandchildren in the years following the flood, he describes what he observed, the whole of the land was covered with water.” (114)

While this is an interesting and innovative suggestion, a closer analysis immediately suggests multiple problems. For example, the primary mechanism for Davidson’s flood is not forty days of torrential rain pouring down from a reservoir held above by a hard dome. Rather, it is a large body of water inundating a low-lying region. In addition, the flooding of the Black Sea was most surely not sufficient to plunk the ark atop Mt. Ararat.

There are additional problems, of course, but at this point, one must ask: what motivates the need to ground the Genesis flood in a historical event? Granted, there may be a vestige of an event in natural history that corresponds with this narrative (one that is also retained in other narratives like the Enuma Elish and the Epic of Gilgamesh), but that doesn’t change the fact that the narrative itself is anything but sober history. Indeed, it turns out that the Noahic is a highly structured chiasm and the center is Genesis 8:1: “But God remembered Noah…” By focusing on a vindication of the text in natural history, we just might miss the point.

I worry that attempts to correlate narratives like the Nephilim and the Flood, texts which are so naturally interpreted as mythic etiological prehistory, with history and science belies the continued influence of the same concordist impulse that drives YEC. And there is also linked to this an apologetic impulse which I also see in Davidson’s work. For example, he cites how modern science is confirming that “the earth gave rise to life” in an echo of Genesis 1: “Let the earth bring forth.” And so he concludes, “The parallel here between the Bible and science is remarkable….” (83) To be sure, Davidson then goes on to argue that we can view that bringing forth as having occurred through divinely superintended natural evolutionary processes. But I worry that it is as misguided to find a “remarkable” evolutionary consonance between Genesis 1 and science as it is to find a “remarkable” special creation consonance.

Next, I’m going to offer a rejoinder to Davidson’s critique of intelligent design in the penultimate chapter. To begin with, he assumes that ID theorists believe the intelligence that is identified by their theory to be supernatural (i.e. God) (258). While this is true of most ID theorists, it is worth noting that a minority are not theists: David Berlinski is agnostic and Bradley Monton is an atheist, for example.

But the bigger issue is that Davidson repeatedly claims that ID theorists seek to identify God from within their theoretical proposals. For example, he writes, “The only logical explanation is that they were created supernaturally by an intelligent designer.” (261) But this is false. Indeed, ID theorists differ precisely from traditional arguments for design on this point, that they do not claim to identify the designer but only to be able to detect the presence of design. One may have additional reasons to identify a designer as God, but those additional reasons will be theological or philosophical rather than being a strict product of the ID argument itself.

Davidson also criticizes ID for assuming a God-of-the-Gaps theology. Technically, this cannot be the case because, as I noted above, ID does not address the identity of the designer. However, I will concede that some versions of ID are more vulnerable to that critique: Behe’s conception of irreducible complexity comes to mind. Bt that is not true of other versions (e.g. those of Meyer and Dembski). Ultimately, the question is not, as Davidson supposes, whether the phenomenon could have come about by natural causes (264). Rather, the question is whether intelligence is the best available explanation for this natural phenomenon. Moreover, the core idea that design is detectable in nature is consistent with nature being a closed continuum of natural causes. (I make that case in chapter 29 of my book The Swedish Atheist, the Scuba Diver, and Other Apologetic Rabbit Trails.) That fact in principle obliterates the charge that the core project of ID assumes a God-of-the-Gaps theology.

This leads us straight into my third and final point. Here my criticism is not focused so much on what Davidson does say as on what he fails to say. In short, he makes only passing reference to miracles and he never clearly lays out a framework for thinking about divine action and how it relates to nature and his own commitment to seeking natural causal explanations for all phenomena in nature. It seems to me that this is an unfortunate lacuna: the book would have benefited greatly from a chapter overview of models of divine action in nature such as the transcendent agent models of historic Thomism and Calvinism as well as the immanent agent models popular among many in the theology/science dialogue today (e.g. Philip Clayton; John Polkinghorne). This would provide the reader with a very helpful theological framework for thinking through issues like methodological naturalism and miracles.

Conclusion

You’ve read my critiques. You can judge for yourself whether they are of merit. But as I close this review I want to point out that even if they are of merit (as I presume they are!), they nonetheless strike at the periphery rather than the heart of Davidson’s project. And the heart of Davidson’s project is to liberate Christians from the baggage of YEC hermeneutics, theology, and rhetoric and for a wholehearted embrace of God’s revelation in the Book of Nature. If you are looking for a thorough, book-length refutation of YEC informed by rich scientific and theological reflections, then Friend of Science, Friend of Faith belongs on your shelf.

Thanks to Gregg Davidson for a review copy of this book.

The post Friend of Science, Friend of Faith: A Review appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 3, 2020

Further Down the Rabbit Hole: An Interview on Ravi Zacharias’ Confabulations

In September 2018, I interviewed Steve Baughman about some concerning allegations pertaining to the conduct of widely revered Christian apologist Ravi Zacharias. In that interview (which I strongly suggest you read before proceeding with this article), Mr. Baughman outlined evidence for some very concerning behavior, including claims that Mr. Zacharias has consistently fabricated details about his academic history as well as that he engaged in sexually predatory behavior.

In September 2018, I interviewed Steve Baughman about some concerning allegations pertaining to the conduct of widely revered Christian apologist Ravi Zacharias. In that interview (which I strongly suggest you read before proceeding with this article), Mr. Baughman outlined evidence for some very concerning behavior, including claims that Mr. Zacharias has consistently fabricated details about his academic history as well as that he engaged in sexually predatory behavior.

Given that it has been more than a year since Mr. Baughman’s book Cover-Up In the Kingdom was released, I decided it was time to return to our conversation in order to find out how evangelicals have received Mr. Baughman’s evidence as well as whether there are any pertinent updates to his concerning case against Mr. Zacharias.

RR: Steve, thanks for agreeing to do a “part-two” for this interview. To begin with, can you talk about how Cover-Up in the Kingdom has been received? Did Mr. Zacharias respond to it? How has it been received by evangelical leaders?

SB: Thank you for being one of the few Christians to take the Zacharias deceptions seriously. To borrow a line from David Hume, my book basically “fell stillborn from the press.” The religious press would not touch it and it garnered precisely zero reviews other than yours, (with a few mentions by relatively obscure bloggers). That said, hundreds of copies are out there and this seems to have generated a behind-the-scenes discussion in various evangelical circles. A prominent Canadian religious broadcaster wrote me and said she read the book in one sitting and that it is “teaching us a tough and needed lesson, and God’s work in our lives is better because of it.” I’m not sure what she means, though. Her network continues to carry Ravi’s show. When I inquired of the network they said Ravi pays his bills and has not violated the broadcaster’s ethical code. So the information is out there, but it seems to have no effect on business as usual.

RR: I can’t say that I’m surprised. Writing a book like that is a thankless task. Not many atheists will be sufficiently motivated to pick it up because many will just say, “I told you apologists are liars for Jesus!” Meanwhile, what Christian wants to sit and read a chronicle of the sins of one of their favorite apologists? Not many, it turns out.

But sometimes you’ve got to write something just because it is important to you. I actually parted ways with my literary agent when I told her I wanted to write a book defending atheists. She told me “That won’t sell!” and she was right. But I’m still proud of Is the Atheist My Neighbor? Well, Cover-Up in the Kingdom fulfilled a similar service.

Now I know that you’ve continued to research Zacharias in the last two years. What more have you discovered since writing the book?

SB: I have three of your books. So I know that at least some of them sell.

April 2, 2020

What’s the biggest problem with annihilationism?

In this low-quality video with abysmal production values, I outline what I think is the biggest theological/philosophical objection to the theory of annihilationism.

The post What’s the biggest problem with annihilationism? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

April 1, 2020

Should theological claims be judged by Popper’s Falsification Criterion?

Today, I’ve gotten into discussions with folks on Twitter about whether Karl Popper’s principle of falsification should be invoked to judge the value/veracity/legitimacy of theological theories. Things got going with my tweet in response to Counter Apologist. (Follow up on Twitter to see our full back-and-forth exchange.)

It's interesting how many atheists assume without question that Karl Popper's controversial philosophy of science provides an unquestionable constraining principle for rational discourse. https://t.co/06AkmHivKM

— Tentative Apologist (@RandalRauser) April 1, 2020

I then offered up five tweets commenting on falsification which I’ve recounted below:

Let me explain what’s wrong with Popper’s criterion of theory falsification to all the lay folk out there. If you discover that your car needs a new transmission, you make a decision as to whether it is worth the cost. If so, you pay up. If not, you turf it. In principle, you could fix your car and keep it on the road in perpetuity (like Cubans do with their 1950s American cars). But you only do so if it is worth it. When the cost exceeds the value, it’s off to the wrecker.

Theories are like that. You can “fix” them interminably, just so long as the cost is worth it. But at some point, the costs of modifying the theory outweigh the value of the theory. At that point, the theory is abandoned. Not falsified, just abandoned. The Ptolemaic theory is a great example with the famous addition of epicycles.

It is theoretically possible that “epicycles” could’ve been continually added to the Ptolemaic theory to adjust it to our current scientific data. Such a theory would be absurdly bloated, ad hoc, and have little to no explanatory value. But it wouldn’t be “falsified”.

So while specific claims in a theory are regularly falsified. The theory itself can always be adjusted to accommodate the counter-data. Well, at least Popper’s theory lived up to its own standard: it was falsified.

Or was it?;)

The post Should theological claims be judged by Popper’s Falsification Criterion? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

March 30, 2020

An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Feisty Secular Audience

When I was a kid, I had a cherished Hot Wheels which disappeared one day. I looked around for a few days and then gave up and got on with my life. A year or two later, I discovered that Hot Wheels in our backyard sandbox, and what a joyous reunion that was!

When I was a kid, I had a cherished Hot Wheels which disappeared one day. I looked around for a few days and then gave up and got on with my life. A year or two later, I discovered that Hot Wheels in our backyard sandbox, and what a joyous reunion that was!

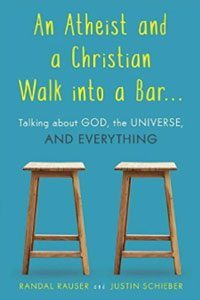

Three years ago, I went on a speaking tour in Arizona with my coauthor, Justin Schieber, promoting our then-new (and still awesome!) book An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Bar. One of the events was with a particularly feisty and at times hostile (that is, hostile to me!) atheist/secular audience. And while it was recorded (and the only event on the tour that was), I never heard whatever happened to it. And so, after a few months, I got on with my life.

Well, looky here! Now, three years later, I got an email from my contact at Freethought Arizona. He said he finally had some time to edit and upload the video (after three years?! Good gosh, somebody busier than I am!). Maybe not quite on the scale with rediscovering my favorite Hot Wheels, but still very cool. Check it out!

The post An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Feisty Secular Audience appeared first on Randal Rauser.