Randal Rauser's Blog, page 60

March 28, 2020

A Short Word on Good Arguments

What is a “strong argument”? This is a question that every apologist should consider. You should start with premises that are true or plausibly true. Next, a conclusion that follows from the premises. That makes it a *valid* argument.

But there’s more. After all, a valid argument with premises which cannot be understood by the target audience isn’t much good. I mean, what good is an argument if nobody understands it? By analogy, what good is a Ferrari consigned to a museum so that nobody can drive it? Ferraris were made to be driven and arguments were made to be understood.

So, we have plausibility, validity, and accessibility. Let’s add one more desideratum: weightiness. It’s not trivial; it has emotional bite; it keeps you up at night, thinking. Now that’s a good argument.

The post A Short Word on Good Arguments appeared first on Randal Rauser.

March 26, 2020

Don’t Sacrifice Your Conscience to Defend Your Reading of the Bible

I’ve been talking about biblical violence on Twitter over the last day. So now I’m back to my blog and drawing on several articles I’ve written over the years all to the end of driving home a singular point: don’t sacrifice your conscience in defense of a particular reading/interpretation of the Bible. If you know something is wrong, don’t do violence to your conscience by pretending otherwise.

Yesterday on Twitter, one of the topics concerned the difficulty with the Torah mandate to pelt insubordinate children to death with rocks. This is wrong on multiple levels and we all know it. But don’t take my word for it. Just read this news article:

(Kabul, Afghanistan) Yesterday reports surfaced of a public stoning in the city of Saidu Sharif in the Swat Valley of eastern Afghanistan. Early reports identify two parents as presenting their thirteen year old son to public authorities for being “stubborn and rebellious”. Town elders gathered together and stoned the boy until he was dead. The Al Qaeda held district of Swat has become notorious in recent months for its enforcement of a strict Sharia law. (Associated Press)

What was your response to that story? Was it a shrug of the shoulders? Or was it a visceral response of moral condemnation? The latter, I hope. And that should tell you something. Your visceral response is telling you that that kind of action is wrong, intrinsically wrong. And to say that it is intrinsically wrong means that it is still wrong even if you swap out “Kabul, Afghanistan” with “Jerusalem” and “Yesterday” with “three thousand years ago”.

So what precisely is wrong? I’m going to address four issues: capital punishment, stoning, killing legal minors, and the parental role.

Capital Punishment

The first issue, the ethics of capital punishment itself, is the one about which reasonable people disagree. But at least some of you will agree with me on this one and so I’m speaking to you. So my point here is directed to folk who agree that there is something wrong, unethical, about state-sanctioned killing. A decade ago, I reviewed the film At the Death House Door which focuses on capital punishment at the Walls Prison in Huntsville Texas. The documentary focuses on Carroll Pickett, a hard-nosed Texas chaplain who used to be very much for the death penalty but has since changed his mind. This is how the review ends:

Even if you could ensure only guilty men die, Pickett now wants nothing to do with it. He now sees capital punishment as a wholly brutalizing practice. It’s that sick mentality that allows a nearby cafe to sell “murder burgers” and for the star attraction at the prison museum to be “Ole’ Sparky”, a retired electric chair. The daughter of a murdered woman summarizes the problem when, following the execution of her mother’s killer, she poignantly observes: “My mother’s dead. He’s dead. That’s just two dead people.” (Source)

If you agree with Pickett that capital punishment is a brutalizing practice, and if you agree with that daughter that it just gives you one more dead person, then you have a good reason to rethink the ethics of child stoning and the Torah punishments more generally.

Stoning

Next, let’s talk not just about capital punishment generally but about the specific practice of capital punishment by stoning, the practice of hurling rocks at a person until they die. Even if you accept that capital punishment can be ethical in principle, I hope you will agree with me that stoning cannot be an ethical form of capital punishment. If you are not convinced, I will direct you to the stoning scene in the film The Stoning of Soraya M which I review here. I have the film set to the beginning of the stoning sequence. See if that doesn’t change your mind:

Killing Minors

The third problem is with the stoning of children (i.e. legal minors). The Deuteronomy 21 passage may not be limited to legal minors, but it surely includes them. So why is it wrong to kill legal minors, in particular? Here I’ll quote from my article “Why it is wrong to execute minors”:

Prefrontal cortex. Interestingly, these intuitions are supported by the fact that the prefrontal cortex, the last part of the brain to reach maturity, affects a broad range of cognitive abilities including, among others, the ability of young people to anticipate the consequences of one’s behavior. (See this helpful discussion for a quick overview.) This is why, for example, teenagers are much more likely to engage in highly risky behavior than adults. (Take a few minutes to peruse the range of idiotic teen stunts memorialized on youtube.)

So consider a legal mandate that says all children who talk back to their parents are to be stoned. A twenty year old can anticipate more fully the consequences of their action than a fifteen year old can. And a fifteen year old can anticipate them more fully than a five or ten year old can. Given this fact, it is recognized that it is wrong to apply to minors the same punishments as one extends to adults, because their prefrontal cortex is not sufficiently developed to anticipate to the same degree the consequences of their actions.

Hormonal changes. According to the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP), the advent of puberty brings with it a range of emotional / behavioral issues in teenagers which are still considered part of normal teenage development. These include changing one’s appearance (e.g. dressing “goth”), withdrawing from various aspects of family life, increased argumentativeness with authority figures, and emotional ups and downs. One shivers to think of how many teenagers undergoing normal patterns of development would emerge as candidates for stoning under the Deuteronomy statute. (Source)

Parenthood

And the final offense is the indescribable sacrilege, the desecration, that this mandate wreaks on the sacred institution of parenthood itself. Parenthood is a beautiful, sacred institution and I had the privilege of entering into it eighteen years ago. Imagine if every time a man and woman became parents, they knew that should the child ever present an especial burden or challenge to their authority, they would always have the option of turning that child over to the village elders to be pelted to death with rocks. That suggestion offends me to my core. I hope it does for you as well.

A few years ago, I was reading through Eugene Merrill’s treatment of this topic in his commentary Deuteronomy: An Exegetical and Theological Exposition of Holy Scripture (B&H, 1994). After ]describing the steps under which the execution would take place in a matter-of-fact way, Merrill explains why it was necessary to pelt insubordinate youth to death with rocks:

“The severity of the punishment appears to outweigh the crime, but we must recognize that parental sovereignty was at stake. Were insubordination of children toward their parents to have been tolerated, there would have been but a short step toward the insubordination of all of the Lord’s servant people to him, the King of kings.”

Mr. Merrill is here defending honor killing. It’s the same logic by which a Muslim father will kill his daughter after she defies him by going out with her western boyfriend. In short, it’s the same twisted logic to which blood-spattered murderers appeal when they are led away in handcuffs.

Don’t be like Mr. Merrill. Don’t sacrifice your conscience in your reading of the Bible. Instead, recognize the gift of your God-given moral intuitions and let them offer chastening guides as you wrestle with the Biblical text.

The post Don’t Sacrifice Your Conscience to Defend Your Reading of the Bible appeared first on Randal Rauser.

March 21, 2020

The Day Christopher Hitchens Beat Five Apologists with a Story

Be a storyteller (mandolin optional)

This morning, I posted the following observation in a tweet:

We will only begin to appreciate the power of the problem of evil when we take the time to consider thick and detailed stories of suffering.

We will only begin to appreciate the power of theodicy when we take the time to consider think and detailed stories of hope and redemption

Underlying that dual observation is a recognition of the power of story. As a case in point, in 2009, I saw Christopher Hitchens debate four Christians in Dallas, TX. (In fact, the first article I ever wrote for a blog was titled “Atheism in Dallas” and it appeared in March 2009 on The Christian Post website. I later reposted it here.)

The one thing I remember about Hitchens’ withering presentation is that it centered on a story, the horrifying case of Josef Fritzl who kept his daughter a prisoner under his house and raped her for close to thirty years. Hitchens described how Fritzl’s daughter would hear him coming down the stairs to rape her and how God never responded to her prayers. In riveting fashion, Hitchens described Elisabeth wincing with every squeak of the staircase as her father descended into the dungeon to victimize her again. The question, of course, is how could God remain unresponsive to Elisabeth’s prayers? The answer, for Hitchens, is that no true god could remain silent. And thus, God does not exist.

While I have a vague recollection of the arguments made by the Christian apologists that day (William Lane Craig, James Denison, Doug Wilson and Lee Strobel as well as the very partisan “moderator”, Stan Guthrie) they were all cerebral and lacked an emotional weight to lodge deep. By contrast, Hitchens’ narration of abuse concealed an iron hook that lodged deep within my memory, such that I remember it vividly more than a decade later: indeed, I shall not likely forget it until the fog of dementia winds its way through my neurons in thirty-plus years.

Now that is the power of story. And on that occasion, the dais featured a powerful storyteller of evil. One can only wish that it has featured an equally powerful storyteller of hope and redemption.

The post The Day Christopher Hitchens Beat Five Apologists with a Story appeared first on Randal Rauser.

March 19, 2020

Christians, you are allowed to wrestle with the problem of biblical violence

A detail from the stoning of Achan (Joshua 7).

Imagine for a moment that you are in conversation with a person from another religion and you discover that their sacred text describes their deity as commanding genocide on entire peoples. If you’re like most people – including most Christians — then this discovery would provide a significant obstacle to you considering that religion any further.

As you may know, the Christian faces a similar dilemma since the Bible appears to depict God as commanding and commending violent actions that appear to be immoral including the mass targeted killing of entire civilian populations (e.g. Deuteronomy 20:10-20; Joshua 6; 1 Samuel 15). Historically, many Christians have not shied away from this fact. Consider, for example, John Calvin’s iron constitution as he describes the carnage that came with the destruction of Jericho:

“Indiscriminate and promiscuous slaughter [of the Canaanites], making no distinction of age or sex, but including alike women and children, the aged and decrepit, might seem an inhuman massacre, had it not been executed by the command of God. But as he, in whose hands are life and death, had justly doomed those nations to destruction, this puts an end to all discussion.”

Given the emotional and ethical challenge presented by these texts, it should be no surprise that the recognition of biblical violence has come to provide an enormous obstacle to Christian belief, and one that has increasingly occupied the resources of many apologists who sought to defend the basic violent depictions, often with some important caveats.

This is certainly an important topic. And given the scope and emotional intensity of the problem, it extracts enormous resources from apologists like Paul Copan to defend the account of narratives that depict God commanding the slaughter of entire towns.

I respect the efforts of apologists like Copan, but personally I find their arguments to be poor and unconvincing. More to the point, however, is the prior question: is the defense of these narratives as such part of the ground level of Christianity? Or is it part of the secondary opinions of the second floor that is maintained by some Christians but not others?

This presses us back to a prior question. Is it part of that ground-level mere Christianity to believe that God commanded actions like the genocidal slaughter of entire peoples? I certainly do not include that claim in my understanding of mere Christianity; nor is it a feature of mainstream creeds and confessions. So why include it at all? Why not instead place it on the second floor as a secondary opinion held by some Christians but rejected by others?

I can imagine those who think this is a really essential, ground-floor belief might respond like this:

acceptance of the fact that God commanded and commended these actions is required on the ground floor because mere Christianity does include a commitment to plenary inspiration and biblical authority. You cannot take your scissors and snip out the bits of the Bible that you don’t like. Instead, mere Christianity requires us to accept the whole counsel of God!

Now I agree with the gist of that response wholeheartedly: plenary inspiration and biblical authority matter! Indeed, they belong on the ground floor of mere Christianity. But I would immediately add that we must be very careful about assuming that some particular reading of scripture is required by that commitment to plenary inspiration and biblical authority.

That said, there is a limited range of topics for which a particular interpretation of Scripture is required at the ground level. That list includes reading the Bible consistently with essential doctrines such as the Trinity and the incarnation and bodily resurrection of Jesus.

But it does not require particular readings of biblical passages that are not part of that ground level. So, for example, the young earth creationist may believe that plenary inspiration and biblical authority requires a reading of the Genesis creation as including literal 24 hour days. They are mistaken.

I’d say the same thing in this case. The ground level of mere Christianity includes a commitment to the plenary inspiration and authority of Scripture. But it does not require one to accept that God literally commanded the slaughter of entire civilian populations any more than it requires that one accept God literally created in six 24-hour days.

Now you might concede the point in principle and nonetheless worry that the pursuit of non-violent readings which depart from the literal and historical reading of those narratival details is a suspiciously modern phenomenon. Are we contorting to, as some theologians like to say, “modern sentimentalism”?

I have several responses. First, one might say that the practice of reading the Bible as repudiating slavery is also a suspiciously modern phenomenon driven by “modern sentimentalism.” But that fact doesn’t lead us to reconsider slavery readings (at least it shouldn’t!). Rather, we retain our “modern” reading while insisting that in these points, at least, the tradition that believed the institution of slavery was consistent with Scripture was wrong.

Second, the modern sentimentalism response fails to recognize just how much historical diversity there is in the Christian tradition when it comes to reading these biblical violence texts. One finds evidence of that discomfort, for example, in the fact that third-century Origen suggested adding a spiritual reading of the violent destruction of Jericho (Joshua 6:16-17). He suggests,

“This is what is indicated by these words: Take heed that you have nothing worldly in you, that you bring down with you to the church neither worldly customs nor faults nor equivocation of the age. But let all worldly ways be anathema to you. Do not mix mundane things with divine: do not introduce worldly matters in the mysteries of the church.”

It’s important to note that Origen never comes out and denies that the destruction of Jericho occurred. Nonetheless, his attempt to add a non-violent spiritualized reading shows an awareness of the moral problems that the text presents and a need to seek additional meanings to help contextualize and so interpret that violence.

An even more striking example comes with Gregory of Nyssa. While Origen’s orthodox legacy is complicated (particular views he held – though not his views on Joshua – have been judged heterodox), Gregory’s orthodox theological legacy is unimpeachable. Indeed, he is one of the most important theologians to define and articulate an orthodox confession of the Trinity in the late fourth century. At the same time, he faced biblical violence with striking candor and directness. In this passage, Gregory takes on the violence in the final plague of Egypt, that which involves the killing of every firstborn son:

“How would a concept worthy of God be preserved in the description of what happened if one looked only to the history? The Egyptian acts unjustly, and in his place is punished his newborn child, who in his infancy cannot discern what is good and what is not. His life has no experience of evil, for infancy is not capable of passion. He does not know to distinguish between his right hand and his left. The infant lifts his eyes only to his mother’s nipple, and tears are the sole perceptible sign of his sadness. And if he obtains anything which his nature desires, he signifies his pleasure by smiling. If such a one now pays the penalty of his father’s wickedness, where is justice? Where is piety? Where is holiness? Where is Ezekiel, who cries, The man who has sinned is the man who must die and a son is not to suffer for the sins of his father? How can the history so contradict reason?”

This is a powerful bit of writing. Gregory is wrestling with the content of what he reads in a way that would make many an evangelical Christian blush. Rather than allow us to get away with an abstract description of the firstborn as an amorphous group, he insists on drawing a thick narrative with the picture of an innocent infant being cradled in the arms of his loving peasant mother. How could God kill this innocent child, holding that baby responsible for the sins of others?

Gregory concludes that it just cannot be so. God could not have done this. Unlike Origen, Gregory is not satisfied simply to add a non-violent spiritual layer of meaning to the text to avert our gaze from the literal carnage. Instead, he appears to propose an alternative spiritual meaning which obliterates the historical reading, as such:

“Therefore, as we look for the true spiritual meaning, seeking to determine whether the events took place typologically, we should be prepared to believe that the lawgiver has taught through the things said. The teaching is this: When through virtue one comes to grips with any evil, he must completely destroy the first beginnings of evil.

“93. For when he slays the beginning, he destroys at the same time what follows after it. The Lord teaches us the same thing in the Gospel, all but explicitly calling on us to kill the firstborn of the Egyptian evils when he commands us to abolish lust and anger and to have no more fear of the stain of adultery or the guilt of murder.”

Is Gregory correct? No doubt, Christians will debate that question. My point here is that it is part of the Christian tradition to wrestle with the biblical text and in particular the violence of Scripture.

And that noble tradition of wrestling with the biblical text as Jacob wrestled with the angel continues today. In recent years, many theologians have proposed various ways of reading and appropriating violent biblical texts. And in all these contexts, the revisionist readings are not simply a matter of biblical exegesis. Instead, they are also formed by attention to extra-biblical sources including secular history (e.g. archaeology) as well as the reader’s moral intuitions. In addition, there are internal biblical principles to guide the interpretation such as the principle that scripture interprets scripture coupled with particular principles like the interpretive priority of the peaceable Jesus in interpreting the entire Bible.

Some people will be uncomfortable with the bald acknowledgment that extra-biblical sources like archaeology can shape the reading of the biblical text. But if the appeal to science makes people nervous, the idea that we might appeal to rational or moral intuitions in our reading of the Bible is even more worrisome.

It shouldn’t be. Our rational and moral intuitions – or conscience – may not be infallible, but they are nonetheless God-given resources for seeking truth and pursuing theological reflection. Conservative Calvinist theologian is a surprising defender of the role of conscience in theological reflection. Some years ago, Piper participated in a written debate with Arminian theologian Thomas McCall on truth of Calvinism. Like many non-Calvinists, McCall has some serious moral objections to Calvinist theology. In response, Piper makes a startling concession: “Do not yet believe what I say. Your conscience forbids it. You dare not believe statements about God which, according to your own conscience, can only mean that God is what he is not.”

I admire Piper for his striking candor in this statement. And it’s worth underscoring the point that he is making. Though he believes Calvinism is both true and very important, he also believes that the individual’s conscience is even more important: thus, if you have a moral objection to Calvinism then you ought not to accept Calvinism.

That which can be said of Calvinism can equally be said of the moral violence attributed to God in Scripture. And that formational guidance from conscience provides a powerful reason for accepting some readings of the text and rejecting others. The ground level of Scripture commits the Christian to plenary inspiration and formation: in other words, all Scripture is given to teach, rebuke, correct, and train in righteousness. But Christians disagree on precisely how we should read various biblical passages in light of this commitment. And the apologist is wise to recognize that variation in interpretation.

Cited in C.S. Cowles, “The Case for Radical Discontinuity,” Show Them No Mercy: 4 Views on God and Canaanite Genocide (Zondervan, 2003), 17.

Paul Copan, Is God a Moral Monster? Making Sense of the Old Testament God (Baker, 2011).

Paul Copan and Matt Flannagan attempt to argue that the texts are not genocidal. Of the Canaanite occupation in particular. See Did God Really Command Genocide? Coming to Terms with the Justice of God (Baker, 2014).

See, for example, “Did God Really Command Genocide? A Review (Part 1),” (January 27, 2015), https://randalrauser.com/2015/01/did-...

John R. Franke, ed., Joshua, Judges, Ruth, 1-2 Samuel, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture: Old Testament IV (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2005), 37.

Gregory of Nyssa, The Life of Moses, trans. Abraham J. Malherbe and Everett Ferguson (New York: Paulist Press, 1978), 75.

Gregory of Nyssa, The Life of Moses, 75-6.

See for example, Greg Boyd, The Crucifixion of the Warrior God, vols 1 & 2 (Fortress, 2017); Douglas Earl, The Joshua Delusion? Rethinking Genocide in the Bible (Wipf and Stock, 2011); Peter Enns, The Bible Tells Me So… Why Defending Scripture Has Made Us Unable to Read It (HarperOne: 2014); Philip Jenkins, Laying Down the Sword: Why We Can’t Ignore the Bible’s Violent Verses (HarperOne, 2012): Eric Seibert, The Violence of Scripture: Overcoming the Old Testament’s Troubling Legacy (Fortress Press, 2012).

You see, according to Calvinism God elects some people for salvation while passively or actively willing those who are not so elected to experience eternal damnation. This doctrine understandably horrifies many non-Calvinists, and McCall makes precisely that point.

John Piper, “I believe in God’s Self-Sufficiency: A Response to Thomas McCall,” Trinity Journal, 29, no. 2 (2008), 234.

The post Christians, you are allowed to wrestle with the problem of biblical violence appeared first on Randal Rauser.

March 17, 2020

No True Christian. No True Muslim

In my recent video review of God’s Not Dead with Capturing Christianity, I criticized the film’s uncharitable stereotyped portrayal of Muslim families. Predictably, conservative Christians pushed back. One fellow on YouTube replied,

@Randal Rauser Usually, that “reason” is that one person makes a superficial outside observation and reads too much into it, then makes up a straw man that gets repeated to everyone else who don’t know real Christians. The other common reason is nut picking, such as focusing on Westboro Baptist Church and ignoring the numerous counterexamples like Cameron. https://youtu.be/xE6Af7f9MBE?list=PLSQlg4QzakovoH1eb0ckfSwRqLHFWy5TM When are professed “Christians” ever this bad? When do they give death threats?

I replied:

@therealhardrock I’m guessing you have no Muslim friends because if you did, you’d recognize that the views you just expressed represent a selected portrait (one popular among conservative American media) which mirrors the uncharitable portrait of conservative Christians common in liberal media.

Your question — when are professed “Christians ever this bad? — suggests you have some rather dark rose tinting on your glasses. Professing Christians commit violent and un-christlike actions all the time. To be sure, you can say “Those aren’t real Christians” but then you fall into the no True Scotsman fallacy.

And the mirror opposite applies as well: my Muslim friends are loving and kind and thoughtful. They are like Izzeldin Abuelaish, the Muslim doctor who wrote a memoir, “I Shall Not Hate,” chronicling his journey of forgiveness for the Israelis that killed his family.

Of course, as you say the true Christians aren’t violent, you can also say the true Muslims are, in which case you can exclude Abuelaish as a false Muslim. And in that way, you can stumble yet again into the no true Scotsman fallacy.

A better way: you could choose to love your neighbor and treat them the way you want to be treated, to get to know some Muslims, and to set aside your stereotypes.

The post No True Christian. No True Muslim appeared first on Randal Rauser.

My Video Review of God’s Not Dead with Capturing Christianity

The post My Video Review of God’s Not Dead with Capturing Christianity appeared first on Randal Rauser.

My Coronavirus Post

At times of the pandemic, some people shelter in their homes in immobilizing fear, stockpile (and then price gouge) hand sanitizer, shake hands indiscriminately with the elderly, and/or buy an extra gun. But others reach out to fearful neighbors to see how they can help, they give an extra bottle of hand sanitizer to a friend, they maintain social distancing but with a warm smile and a wave, and they leave the gun in the store.

And then there’s me, tweeting about it all sanctimoniously from my study. But kidding aside, I hope I’m found in the second group.

Be safe, be brave, be kind.

The post My Coronavirus Post appeared first on Randal Rauser.

What Does It Mean to be a Tentative Apologist?

It was the summer of 1996 and I was taking my first course in graduate school. The course was taught by Australian New Testament scholar Paul Barnett on the historical Jesus. After class, I was chatting with another student about the reasons we were taking the class. I still recall saying to him, “I’m taking the class because I love apologetics. And while I have good arguments for all major Christian beliefs, my one weak spot is the historical Jesus, so I’m taking this class to fill that one remaining gap.”

It was the summer of 1996 and I was taking my first course in graduate school. The course was taught by Australian New Testament scholar Paul Barnett on the historical Jesus. After class, I was chatting with another student about the reasons we were taking the class. I still recall saying to him, “I’m taking the class because I love apologetics. And while I have good arguments for all major Christian beliefs, my one weak spot is the historical Jesus, so I’m taking this class to fill that one remaining gap.”

That one remaining gap?! Wow. Even now, more than twenty years later, I can’t help but do a facepalm as I reflect on the naïve hubris of that statement. To be fair, even as I said it, I can recall thinking I sounded rather silly. But that doesn’t change the fact that I did say it in the first place: as if a 23-year-old with a Bachelor’s degree might have mastered almost all the major arguments and evidence for and against Christianity.

[Insert facepalm emoji here]

In many ways, the ensuing years have been one long dismantling of that young man’s naïve and self-congratulatory self-perception. And the best example of my chastened self-perception is found in the fact that when I began blogging in 2009, I chose to call myself “The Tentative Apologist.” To be “tentative” is to be “unsure; uncertain; not definite or positive; hesitant,” “not fully worked out or developed.” So while I was a confident and self-assured young apologist in 1996, more than two decades later I would now describe myself as … tentative.

I’m not the first person to stumble upon the fact that humility and chastened self-awareness reflect deepened wisdom, knowledge, and self-awareness. Consider that famous moment in Plato’s Apology when Socrates declares:

“I am wiser than this man, for neither of us appears to know anything great and good; but he fancies he knows something, although he knows nothing; whereas I, as I do not know anything, so I do not fancy I do. In this trifling particular, then, I appear to be wiser than he, because I do not fancy I know what I do not know.”

Wisdom is found in gaining awareness of what you do not know. By that standard, my 1996 self was woefully ignorant. And if there is one way to capture the ensuing years, it would be by identifying the chastened self-awareness that comes with coming to know how much I don’t know.

http://www.dictionary.com/browse/tentative

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/tentative

The post What Does It Mean to be a Tentative Apologist? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

March 14, 2020

Antinatalism: A Rebuttal

This week’s edition of “Unbelievable” features a debate/dialogue on antinatalism between anti-natalist philosopher David Benatar and Christian philosopher Bruce Blackshaw. Benatar is the world’s leading philosophical defender of antinatalism, a philosophical position that attributes a negative value to the origin of new human life. Thus, on the antinatalist perspective, it would be better, all things being equal, if human beings would cease to exist individually and collectively.

All in all, the conversation was somewhat disappointing. While Benatar offered a solid defense of his views, Blackshaw frankly did not have much by way of rebuttal. He cited Ephesians 1 to support the general claim that it is good for human beings to exist generally, but this seems a misguided use of the text since Ephesians 1 is addressing, specifically, the election of the church.

What really puzzled me about Blackshaw is that he never mentioned the so-called Creation Mandate of Genesis 1:28:

God blessed them and said to them, “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.”

In my view, this text provides the cornerstone for a Judeo-Christian rebuttal of antinatalism.

Intuitions and Counterintuitive Arguments

Before I get there, however, let me begin by highlighting a point that was adumbrated a few times during the program: there is something deeply counterintuitive about antinatalism even if Benatar’s arguments are valid and appear to have plausible premises. This is a not-uncommon situation in philosophical argument. And if an argument violates deeply-seated intuitions, one can either bite the bullet and toss the intuitions, or reject the argument and save the intuitions. And depending on how deeply-seated those intuitions are, it may indeed be perfectly rational to reject a seemingly sound argument, even if one is not sure where the problem lies.

Creation Mandate as Blessing

Fortunately, the Jew or Christian who recognizes the significance of Genesis 1:28 can say more. Let’s begin by noting that this text should not be thought of as a command but rather as a blessing. And viewing a new life as a blessing rather than in terms of the antinatalist’s negative ascription is far more in keeping with normal human intuitions the world over. Every culture celebrates new human life as a good. Benatar may think that’s a mistaken view which is unmasked by his argument, but the person who accepts Genesis 1:28 can reason as follows:

(1) If a perfect being holds a particular belief about moral value and worth, then human beings ought to hold that belief about moral value and worth.

(2) God is a perfect being.

(3) Therefore, if God holds a particular belief about moral value and worth, then human beings ought to hold that belief about moral value and worth.

(4) The belief that new human life is a blessing is a belief about moral value and worth.

(5) God believes new human life is a blessing.

(6) Therefore, human beings ought to hold that new human life is a blessing.

To sum up, this argument has the benefit of comporting with nearly universal intuitions about the blessing that is new human life.

It should also be noted that the above argument applies to individual new human lives. I’ll now turn to another approach which switches from viewing individual lives as a blessing to the fecundity of the human species in general as a blessing.

Creation Mandate as Command

While the Creation Mandate is primarily a blessing or gift, that blessing also brings with it an obligation. The obligation could be rooted in a general observation that when you receive a great gift from a morally noble person who wishes to bless you with the gift, it would be ungracious to reject that gift and consequent blessing. In other words, you have an obligation to accept and be grateful for the gift.

In this case, the blessing is not the fecundity of any specific person or couple but rather the general observation of that the human species is blessed with the great gift to produce more of our kind, and the rejection of that gift would express an improper ingratitude. So the human species, on the whole, has an obligation to embrace and be grateful for the species gift of fecundity rather than an antinatalist position in which we reject and are ungrateful for that gift.

Christian antinatalism

At one point in the show, Benetar touched on the concept of Christian antinatalism based on the threat of hell. Interestingly, almost one year ago exactly (March 13, 2019), I posted an argument for Christian antinatalism. However, if my argument is successful it could equally be viewed as an argument for Christian universalism rather than Christian antinatalism. Based on the Creation Mandate, it would be far more plausible to accept evangelical universalism rather than antinatalism.

The post Antinatalism: A Rebuttal appeared first on Randal Rauser.

March 12, 2020

The extraordinary claim that Christianity is irrational

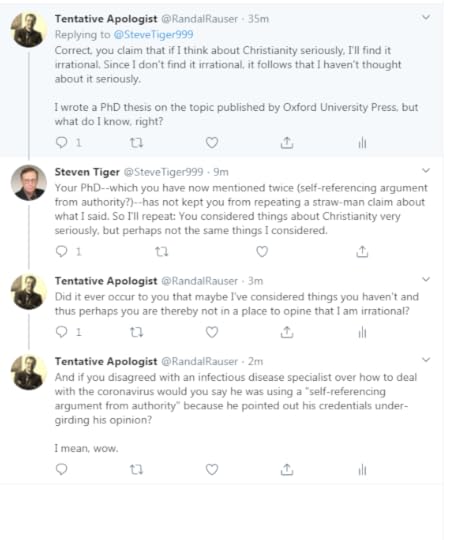

This happens a lot: atheists online tell me that my beliefs are “absurd” or (only slightly more charitably) that I’m “irrational”. Here is an example of an exchange with a gentleman named Steven Tiger. He begins by taking the view that Christianity is ridiculous. Then he modifies it to the view that it is irrational and the fact that I don’t agree is attributable to the fact that I have not considered the things that he has considered.

This happens a lot: atheists online tell me that my beliefs are “absurd” or (only slightly more charitably) that I’m “irrational”. Here is an example of an exchange with a gentleman named Steven Tiger. He begins by taking the view that Christianity is ridiculous. Then he modifies it to the view that it is irrational and the fact that I don’t agree is attributable to the fact that I have not considered the things that he has considered.

To be sure, it’s easy to find folks online who will say such things. However, I bothered to recount this exchange here for a few reasons. First, Mr. Tiger isn’t simply a troll: he wrote a (self-published, I assume) book of more than 300 pages chronicling his journey. Second, Mr. Tiger exhibits very common but troubling behavior of making extraordinary and tendentious claims — such as that all folks who do not agree with him are irrational and/or (non-culpably?) ignorant — and then reacting with indignation when called out on the extraordinary and tendentious nature of those claims. Finally, he also criticizes me for making the wholly legitimate observation that I am not a rube who just fell off the wagon: I have a terminal degree in the relevant field. What is more, I’ve written several books outlining and defending my views including, as I note below, an academic monograph published by Oxford University Press. And I’ve participated in many debates including this debate on the now-defunct Reasonable Doubts podcast in which I argue against the precise claim that Mr. Tiger is making, namely that Christianity is irrational:

https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/tentativeapologist/rd_extra_debate_hallquist_vs_rauser.mp3

Anyway, here’s our exchange for what it’s worth. The modest lesson I’d like to press here is one of epistemic humility. Don’t make sweeping assertions about the irrationality of those who don’t agree with you that you cannot defend. That looks provincial and small-minded. Instead, recognize that rational people disagree with one another all the time and that is true in matters of religion and metaphysics as surely as any other topic.

The post The extraordinary claim that Christianity is irrational appeared first on Randal Rauser.