Randal Rauser's Blog, page 146

August 4, 2016

Mystics, Skeptics, and Nothing Buttery

In The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat Oliver Sacks offers an interesting neurological account of the visions of the great mystic Hildegard of Bingen. Sacks recounts one of Hildegard’s writings titled “The Fall of the Angels” where she describes witnessing the fall of Satan and his minions: “I saw a great star most splendid and beautiful, and with it an exceeding multitude of falling stars which with the star followed southwards … And suddenly they were all annihilated, being turned into black coals … and cast into the abyss so that I could see them no more.” (Cited in The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat (London; Picador, 1986), 161).

Sacks then offers his own analysis: “Our literal interpretation would be that she experienced a shower of phosphenes in transit across the visual field, their passage being succeeded by a negative scotoma.”( 161) Fair enough, Sacks’ “literal interpretation” may be correct insofar as “literal interpretation” = an account of the neurological processes underlying Hildegard’s vision.

However, I suspect that by “literal interpretation” Sacks really intends to refer to “What was really happening.” In other words, Hildegard was experiencing a shower of phosphenes in transit across her visual field which she interpreted as falling stars. And that’s all there is to it.

Again, that may be. But let’s just be clear: that isn’t an argument. Rather, it is a reductive interpretation. In his modern classic The Clockwork Image: A Christian Perspective on Science (InterVarsity, 1974) Donald MacKay famously referred to the leap from “This is x” to “This is nothing but x” as “nothing buttery”.

But wait, what about Ockham’s Razor? Don’t multiple entities beyond necessity, right? So if you can explain Hildegard’s vision by appealing to that shower of phosphenes alone, why tag on a spiritual reality? Doesn’t the physical explanation render the non-physical otiose?

Possibly, but the fact is that we regularly adopt richer explanations if we believe our experience warrants that richer interpretation. For example, you could explain the rich panoply of conscious experience without positing a physical reality: after all, we could just be minds in the matrix. But even if we don’t have a rebuttal to reductive, idealistic accounts of conscious experience, most of us will happily dismiss such nothing buttery as insufficient. Consciousness may be sensory experiences in the mind, but one can believe it is also more than this. All Hildegard need do is apply the same principle to her visions: they may be showers of phosphenes, but that doesn’t mean that they can’t also be visions.

August 3, 2016

The Top Five Reasons Millennials Are Leaving The Evangelical Church (According to ME)

Here is my countdown of the top five reasons millennials are leaving the evangelical church. This list was compiled after extensive field research in which I interviewed several hundred millennials from across North America at various independent bohemian coffee shops.

Okay, not really. I just made this list up off-the-cuff this morning. But here are my top five reasons excerpted from interviews with millennials that never actually took place:

So here goes:

Reason 5: “The youth group at our church is fundraising for a bus trip to visit Ken Ham’s Ark Encounter. Seriously?”

Reason 4: “My church removed the beautiful old oak pews from our sanctuary and replaced them with reclining theater seats and cup holders.”

Reason 3: “I’m still pro-life, but my church never talks about a range of other important social and ethical issues, like militarism, the environment, a living wage, student debt, and immigration reform.”

Reason 2: “My entire small group is campaigning for Donald Trump and against ‘Crooked Hillary’.”

And the top reason millennials are leaving the evangelical church?

Reason 1: “My church used to deny that climate change was happening. Now they are enthusiastically embracing it as a sign of the end times (2 Peter 3:7, 10).”

August 2, 2016

The First Blurb for An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Bar

Yes folks, the first blurb for An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Bar has come in courtesy of one of the best younger apologists in the business, Trent Horn. Trent is the author of Answering Atheism: How to Make the Case for God with Logic and Charity, Persuasive Pro Life: How to Talk about Our Culture’s Toughest Issue, and the newly released Hard Sayings: A Catholic Approach to Answering Bible Difficulties. He also regularly appears as a guest on the popular Catholic Answers radio show and he’s an excellent debater: See his recent debate with Richard Carrier, for example.

Trent writes:

“A refreshing book with perfect sparring partners! Justin and Randal insightfully refute bad arguments related to atheism and also highlight issues that need more attention within the popular debate over God’s existence.”

August 1, 2016

Donald Trump declares his power over the past, can prevent Russia from entering Ukraine

Donald Trump continues to dazzle the world with his geopolitical acumen and extraordinary metaphysical powers. It all began on Sunday when Trump said that Putin is “not going into Ukraine.” George Stephanopoulos replied by pointing out that Russia is already in Ukraine:

Alas, Mr. Stephanopoulos’ response suggests the cynical assumption that Mr. Trump was ignorant of the fact that Russia was already in Ukraine. Clearly that is impossible since Mr. Trump consults himself on geopolitical matters, and since he has a “very good brain” he would obviously have informed himself of the fact that Russia had troops on the ground in Ukraine.

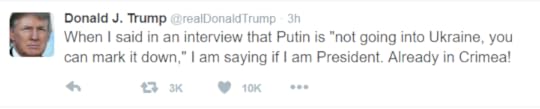

So if it is impossible that Trump could have glaring ignorance just what was Mr. Trump saying? Fortunately he explained this morning in a tweet:

In this tweet, Mr. Trump explains that if he becomes president, he will causally effect the past to ensure that Putin never entered Ukraine in the first place. Admittedly, some in the cynical lamestream media may doubt Mr. Trump’s ability to change the past (I’m looking at you, George Stephanopoulos). In reply, I would suggest those cynics remember that Mr. Trump only makes such extraordinary declarations after consulting his “very good brain.” And very good brains don’t make mistakes.

Unlike Hillary Clinton with her impotence to change the past, Mr. Trump has the real power to make America great again. Perhaps after changing the geopolitical recent past of Ukraine, he can also use that power for other noble tasks, like making Batman v. Superman: Dawn of Justice into a good movie.

The Problem of Evil and Mindfulness

The problem of evil has been stated in many ways but the essence of the objection is that the amount, intensity, and distribution of the evil in the world is inconsistent with the existence of a God that is perfectly good and all-powerful. The standard theistic rejoinder is that God has morally sufficient reasons for allowing that amount, intensity, and distribution of evil that we do, in fact, find. Thus, the theist concludes, the evil in the world does not provide a reason to disbelieve/doubt God’s existence.

As a theist, it seems to me that non-theistic skeptics frequently draw their skeptical conclusions without expending a great deal of effort in trying to understand the ways that evil and suffering might lead to greater goods. For those willing to look, one can find different elements for a theodicy appearing in some rather surprising places, including cold water surfing.

This morning I was watching a TED Talk by surf photographer Chris Burkard as he described the lure of surfing in harsh, bone-chilling conditions. Burkard reflected,

“When it comes to pain, psychologist Brock Bastian probably said it best when he wrote, ‘Pain is a kind of shortcut to mindfulness. It makes us suddenly aware of everything in the environment. It brutally draws us in to a virtual sensory awareness of the world much like meditation.'”

As painful as his experience of surfing in the Arctic could be, Burkard also found it a portal to a depth of experience, a connection with reality, that he could never find in the comparatively benign warmth of the tropics.

Bastian’s insightful quote reminded me of a famous passage from C.S. Lewis’s book The Problem of Pain. Lewis wrote:

“We can rest contentedly in our sins and in our stupidities; and anyone who has watched gluttons shovelling down the most exquisite foods as if they did not know what they were eating, will admit that we can ignore even pleasure. But pain insists upon being attended to. God whispers to us in our pleasures, speaks in our conscience, but shouts in our pain: it is His megaphone to rouse a deaf world.

Lewis’s gastronomic reference calls to mind my own modest experiences with fasting. On two occasions in the past I fasted from food for one week. During that time I predictably suffered physical deprivation. But the loss of food was accompanied by a deepened awareness of food, my physical environment, and a mindfulness of myself. How often had I been the glutton shoveling down foods without really tasting and experiencing them? The fact is that it was through a period of fasting that I became more deeply acquainted with the sensory delight and physical nourishment of mundane meals.

How many pains could be permitted as means to greater mindfulness, as an occasionally brutal means to draw us into a greater sensory awareness of our world, our selves, and our God?

This is a complicated question, and like so much in life, it does not admit to a simple or easy answer. But it does suggest the value of an epistemic humility on the side of the skeptic.

July 29, 2016

Wayne Grudem’s Endorsement of Donald Trump and the Moral Bankruptcy of Evangelicalism

Popular Christian Protestant evangelical theologian Wayne Grudem just endorsed voting for Donald Trump. Grudem is an important figure in the evangelical world, not least because he is the author of perhaps the most popular systematic theology published in the last twenty+ years. (Grudem’s Systematic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine has over 660 reviews at Amazon.com averaging 4 1/2 stars. What is more, his book, published 21 years ago, is currently listed as a “bestseller.” A nobody like myself can only dream of such enduring publishing success.)

Despite his status as a conservative evangelical spokesperson, and “a professor who has taught Christian ethics for 39 years…” Grudem has squandered it all in his article “Why Voting for Donald Trump Is a Morally Good Choice” by endorsing a psychopathic demagogue/despot-in-the-making.

Why?

Grudem explains: “there is nothing morally wrong with voting for a flawed candidate if you think he will do more good for the nation than his opponent. In fact, it is the morally right thing to do.”

Oh really? Without belaboring the point, I’ll simply note that by this analysis a person who believed Adolf Hitler was the man for the job would be doing the right thing by voting for him. Objective moral facts be damned, subjective perception is apparently all that matters.

Grudem’s article is a luminously clear example of a conservative that sold his soul to the GOP. Trump’s psychopathic behavior, no matter how debased, can all be forgiven so long as we don’t elect Hillary Clinton, a candidate who would surely nominate a “liberal” justice to the Supreme Court.

Grudem then goes on to explain how important it is to avoid a “liberal” justice. For example, he has the gall to suggest that a vote for Trump would protect “religious freedom.” That, of course, is code for evangelical Christian religious freedom. Grudem clearly cares nothing for the religious freedom of Muslims or any other minority group outside his own tribe. Shame on you Wayne Grudem.

Grudem’s self-centered concern is even clearer on his next point, the desire to protect “Christian business owners.” Yes, let’s protect the business owners, so long as they’re Christian. Who gives a fig about Muslim, Sikh, or atheist business owners? It’s the Christians that we should care about.

Grudem then adds that Trump would also protect Christian schools and churches. Again, it’s clear the man cares nothing about non-Christians schools and non-Christian places of worship.

Grudem prattles on, listing several other points he believes Trump can secure, all while neglecting to note that Trump is a debased, narcissistic brute who is probably a clinical psychopath.

Along the way, it is extraordinarily revealing to note that Grudem never once considers a single modicum of goodness which may come from a Hillary Clinton presidency. This is an example of a man who has sold his soul to a political party such that he is simply unable of thinking beyond the confines of his own idolatry.

If you want an example of why people walk away in disgust from the evangelical church, you need look no farther than this farcical defense of a demagogue simply because he promises to grant some special favors to your community. Here you have a theologian who, after teaching “Christian ethics for 39 years,” can only provide a defense of a demagogue that would work equally well in Germany circa 1932.

A Bully for President?

Donald Trump is many things: a father, husband, businessman, snake-oil salesman, self-absorbed narcissist, and psychopath. But he’s also a bully. And this short video from the final day of the DNC illustrates his bullying in the classic mode of the Hollywood bully. While the film includes many notable bullies, it misses one of the best, “Moody” (played by Matt Dillon) from the classic 1980 movie My Bodyguard. That lacuna aside, this is a very well executed take-down of perhaps the most noxious figure in public life.

July 28, 2016

Share Your Candidate for the Best Argument Against Christianity

Just over a month ago I wrote an article inviting my readers to “Share Your Candidate for the Worst Argument Against Christianity.” It is now time to offer the complementary invitation of sharing your candidate for the best argument against Christianity.

What do I mean by “best”? Well, for starters one expects that the argument will be valid (deductive; inductive; or abductive). But you need not bother articulating and numbering premises. More often than not in life we communicate our arguments as enthymemes (i.e. an argument in which one or more premise is not explicitly stated). And you’re free to share your argument in that form if you prefer.

Next, we must keep in mind that calling an argument the “best” is a value judgment relative to particular criteria. I have stipulated that validity is a necessary criterion for qualifying as “best”. But beyond that I’m leaving the evaluative criteria open. Thus, some folks may define the “best” argument as the one they find personally compelling, that is, the argument that was for them a catalyst for fomenting (or sustaining) skepticism about Christianity. Others may define the “best” argument as one that they will anticipate appealing to the widest constituency, even if they have not found it personally compelling. And so Christians are especially welcome to submit their best arguments against Christianity. There is no right or wrong here, but only different definitions of “best”. If you like, feel free to articulate the criteria by which you are measuring “best”, though that is not required.

Finally, keep in mind that an argument against Christianity need not target explicitly Christian content. Thus, while one argument may target the historicity of the resurrection of Jesus, another may target the existence of a perfectly good God. While only the former argument is specified to Christianity, each of them targets an essential Christian belief, and thus each qualifies as an argument against Christianity.

July 24, 2016

Can a person be a fundamentalist about atheism?

The question was posted by Mike D in reaction to my article “Atheist Fundamentalism Lives.” Mike writes:

“How can you be a fundamentalist about something that has no doctrines, creeds, or dogmas? That’d be like writing a dissertation about the richness of TV programming on the “off” setting.”

Mike goes on to state that atheists certainly can be fundamentalists about different things (secular humanism, perhaps) but not about atheism per se. Is that true?

Let’s start here: I accept the traditional definition of atheism as the belief that no God exists (or no gods exist). Thus, I’m not interested in those folks who call themselves atheist but only mean that they are merely “without belief in God.” My focus is on those for whom atheism entails at least one belief, the belief that God doesn’t exist or that no gods exist.

Can you be a fundamentalist with respect to that one belief? Well yes, you can.

But let’s back up by starting with a few words on the meaning of fundamentalism. This term was coined in the wake of the publication of The Fundamentals, a collection of twelve pamphlets commissioned by rich oilman Lyman Stewart a century ago as a way to galvanize conservative Christians in North America against the encroachment of liberal Christianity. Consequently, The Fundamentals aimed to provide a restatement of what the authors perceived to be Christian orthodoxy, a return to the central dogmas or fundamentals of Christian faith.

That might be the historic origins of fundamentalism as a concept, but of course concepts change over time and this one is no different. Today the term has been expanded to refer to various religious movements that seek to return a broader religious community to a perceived fidelity to particular beliefs and practices. Even more broadly, the term is defined as follows: “strict adherence to any set of basic ideas or principles.” (dictionary.com)

In my own analysis, I understand fundamentalism to be embodied in two traits: (i) anti-intellectualism about particular fields of formal study and (ii) a sharp binary opposition between reason (those of the in-group) and irrationality (those of the out-group). Thus, I would identify an individual as fundamentalist if they appeal to (i) and (ii) as a means to defend and propagate their core beliefs.

From this it follows that any atheist who engages in (i) and (ii) as a means to defend and propagate the belief that God doesn’t exist (or that no gods exist) constitutes an atheist fundamentalist.

So do any atheists do that?

Let’s begin with anti-intellectualism. Atheist fundamentalists regularly reject specific fields in the humanities. The first target is the literary and historical study of the Bible. The assault on formal literary study of the texts is evident when atheists dismiss the Bible as a primitive collection of Near Eastern iron age fairy tales. The historical assault is evident when atheists cavalierly dismiss a broad consensus on an issue like the existence of Jesus by endorsing fringe mythicist theories. (This particular example is a close parallel with the Protestant fundamentalist’s rejection of a consensus in biology and earth science on the age of the earth in favor of their young earth scientists.)

A second target is theology as with Dawkins’ infamous response to critics that he was ignorant of theology by dismissing the entire discipline as equivalent to “fairyology”.

Finally, we get the attacks on philosophy as with the atheist who poses the incredulous refrain “What have we learned from philosophy?” Ironically, this question typically is motivated by a philosophy of philosophy, as in the naturalization of philosophy which was popularized by philosophers like W.V. Quine. If some question philosophy in principle, others target particular fields of philosophy. And that’s where we situate Loftus’ deluded attempt to rid the world of philosophy of religion, a project as absurd (if not as grand) as Ken Ham’s Kentucky ark.

What about the sharp binary opposition between the reasonable in-group and the unreasonable out-group? In religious fundamentalism the line is often drawn between those who have been illuminated by God’s Spirit (or some other supernatural agent of revelation) and those who remain in darkness. In atheist fundamentalism we find a very similar binary opposition although here the categories are tweaked to pit “reason” against “faith.” But it is fascinating to see how closely the binary opposition of atheist fundamentalists echo their religious counterparts, even down to the contrast between darkness and the unveiling of a new understanding of the world. Exhibit A in this regard is Loftus himself who, as I have noted, endorses a conversion to atheism which is as baldly conversionist as any revivalist preacher. See my discussion in “Why I Became an Atheist”: A Review (Part 1).”

So yes, even a minimal belief like “God doesn’t exist” or “no gods exist” can be held in a fundamentalist way insofar as it is defended and propagated through (i) anti-intellectualism and (ii) sharp binary oppositions. And thus an atheist can indeed be a fundamentalist qua atheism.

July 22, 2016

Keith Olbermann argues that Donald Trump is a psychopath (but we already knew that)

In this twenty minute video (which was just posted yesterday) Keith Olbermann goes through psychiatrist Robert Hare’s Psychopathy Checklist to argue that Donald Trump qualifies as a psychopath.

Unfortunately, Olbermann mistakenly describes this as a “sanity test”. Psychopathy is a personality disorder, not a matter of insanity. And since Olbermann is not a psychiatrist trained in the proper administration of the psychopathy checklist, we should remember that this certainly is not a formal diagnosis.

Nonetheless, this video provides a good overview of the case for that diagnosis along with some levity … including a very amusing allusion to Lloyd Bentsen’s legendary take-down of Dan Quayle.

But what isn’t so funny is that the United States could conceivably elect a psychopath in November.

(Hat tip to Bob for drawing this to my attention.)