Randal Rauser's Blog, page 143

September 12, 2016

Should additions to the biblical texts be treated as canon?

Occasionally I get asked about the canonical status of additions and interpolations to the original writings of the New Testament. (The Old Testament is a somewhat different matter since the original forms of the texts that comprise this collection is shrouded in the mists of antiquity in a way that it is not for the New Testament documents.) The most common additions for which I hear the question raised are the doxology for the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6:13), the longer ending of Mark (16:9-20), and the pericope of the woman caught in adultery (John 7:53-8:11).

One can always dispute the consensus of scholarship and insist that one of these alleged additions is, in fact, original to the text. For example, Nicholas Lunn makes just such a case regarding the longer ending of Mark.

I am not a biblical scholar, so I’ll leave those questions to the experts. Instead, I’d like to pose a different question. Let’s grant that the consensus in all these cases is correct and that these texts do all constitute later interpolations. Does it follow that they ought not be granted canonical status? Does it follow that they ought to be relegated to the footnotes?

It does if one assumes that only the original form of the text is canonical. But why assume that? If God is the primary author/editor/former of these texts, is it not possible that God was not finished with Matthew, Mark, or John at the same time as the original author? In that case, removing these passages (a common practice in contemporary Bibles for the Prayer doxology and longer ending of Mark but not the adultery pericope) would constitute disregarding the intentions of the (divine) author by retreating to an earlier draft of the document.

To be sure, my claim is not that every addition which has made its way into the texts subsequent to their original composition should be retained. (With the exception of KJV Only advocates, one would expect few advocates for returning to the 1 John 5:7 interpolation, for example.)

That, in turn, raises an obvious question: how does one choose which interpolations/additions to retain and which to excise? Why are we comfortable with clipping 1 John 5:7 and (perhaps) Mark 16:9-20, but keen to retain John 7:53-8:11? And why do we keep praying Matthew 6:13 even when so many contemporary Bibles have already banished it to the footnotes?

These are all good questions, and they deserve further attention. But let’s proceed with the discussion disabused of the unquestioned assumption that the oldest form is the preferred form.

The post Should additions to the biblical texts be treated as canon? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 11, 2016

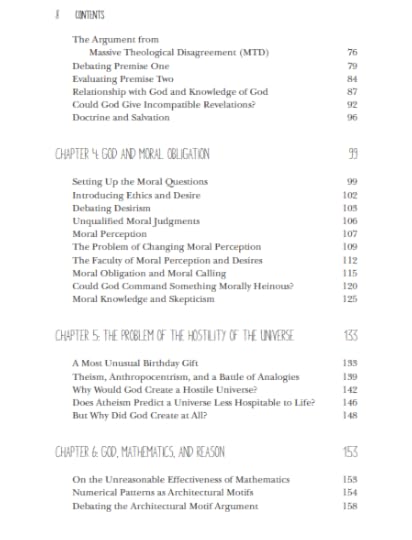

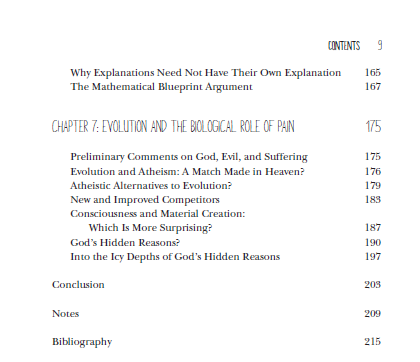

An Atheist and a Christian Walk Into a Bar: The Table of Contents Revealed!

Note: these are screenshots from the PDF of the final pre-publication version of the book. Be sure to pre-order your copy today!

The post An Atheist and a Christian Walk Into a Bar: The Table of Contents Revealed! appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 10, 2016

How the British Humanist Association Promotes Propaganda

This is my second critique of the British Humanist Association video “How do we know what is true?” In my first article on the topic I pointed out how the video tacitly endorses scientism and thereby undermines the value claims upon which humanism is predicated. It is now time to turn to the deeper and more troubling aspect of the video.

In this second article I am going to focus on the way this short video constitutes propaganda since it seeks to further the interests of the British Humanist Association by caricaturing the views of “non-humanists” (the out-group) by way of indefensible binary oppositions that inhibit critical thinking and thereby encourage indoctrination into the secular ideology of the in-group.

In order to make my case, I want to begin by summarizing two questions that can serve to identify whether the video constitutes propaganda and indoctrination. As you watch the video ask yourself these questions:

(1) Does this video seek to cultivate a charitable and nuanced engagement with the views of non-humanists?

(2) Does this video caricature/strawman the views of non-humanists?

If the answer to (1) is “no” and the answer to (2) is “yes” then that provides evidence that the video constitutes propaganda and thus aims to further humanism by undermining critical thinking and indoctrinating the viewer.

Once again, let’s begin with the 2 minute video:

Now we can turn to analysis.

Indoctrination in the Video

Let’s start by taking a look at the content of the video. Immediately the narrator (Stephen Fry) begins by presenting the viewer with a stark binary opposition between two groups. As will become clear in a moment, the contrast is between the humanists who believe science is the way to gain knowledge of the natural world and the non-humanists who believe that supernatural revelations, visions, and inspired books are central to gain knowledge of the natural world.

As Fry explains, the in-group (humanists) accept the “normal” senses and gain knowledge of the world by “carefully and in detail, forming ideas about why things behave as they do, testing those ideas through experiments, refining them in the light of experience, then testing them again.” Fry summarizes that the humanists gain knowledge of the world by “observation,” “experimentation,” and the “testing of theories against evidence.”

Contrast this with the non-humanists who believe in a supernatural reality that includes cartoonish “ghosts and goblins, gods and demons”. These people “have thought that knowledge can come from this [supernatural] source, from revelations, prophetic visions, or divinely inspired books….”

Note that Fry does not say the non-humanist depends wholly on supernatural revelations. Rather, he says that their knowledge can come from this source. Nonetheless, this is a nuance in the narrative that can readily be lost on the casual listener who sees two stark alternatives emerging: that of the humanist (the scientific way) and the non-humanist (the supernatural, revelatory way).

Fry drives the point with the following stark choice:

“If asked to choose between taking a medicine prescribed by a doctor whose methods are based on experiment and one who has selected medicine for you based on his visions, you will probably not choose the medicine from the vision.”

Clearly that choice is the apex for the argument: a decision between two different ways to approach reality, the way of humanism and science or the way of non-humanism and its world of visions, revelations, goblins, and who knows what else.

At that point Fry concludes by waxing eloquently on the humanist’s way of engaging the world — i.e. science — as the best method to know reality.

So let’s return to our two questions:

(1) Does this video seek to cultivate a charitable and nuanced engagement with the views of non-humanists?

(2) Does this video caricature/strawman the views of non-humanists?

How does the video fare? Let’s look at the evidence.

A closer look at Humanist Propaganda

The video’s epistemology appears to be a grossly naive empiricism/scientism. As I pointed out in my first article, it is simply false to claim that all knowledge is gained through science. But as many philosophers have pointed out, scientism isn’t merely false, it’s self-defeating since the core claim “All knowledge is gained through science” is itself not a product of science.

That said, let’s now turn our attention to that ideological wall that Fry uses to divide the humanist and the non-humanist. Let’s begin with the non-humanist. I have never met a non-humanist (i.e. a person who did not identify themselves as a humanist) who denied all scientific knowledge and claimed that they regularly form their beliefs based on revelations and visions from another realm. Perhaps there are such people out there but if there are, they most surely are not broadly representative of the non-humanist group.

In fact, epistemologically speaking non-humanists are like humanists for most of life. Both humanists and non-humanists form beliefs in a number of ways including sense perception, proprioception, memory, testimony, intuition and reasoning processes. (More on those different ways below.)

Consequently, to represent the non-humanist group with a person who advises taking medicine based on a vision is nothing more than an absurd strawman caricature. There may be such people, but they are hardly representative of the group!

Sorry Mr. Fry, but non-humanists don’t regularly consult crystal balls or have seances as guides to navigate the world. We also use our sense perception. We also engage, formally and informally, in observation, experimentation, and the testing of theories against evidence.

What is more, some of us do surprisingly well at that whole science thing. But don’t just take my word for it. Let me give you an example close to home (literally). I attend church at Greenfield Community Church in Edmonton, Canada. One of my fellow congregants is Aksel Hallin, the Professor and Canada Research Chair for Astroparticle Physics at the University of Alberta. Twenty years ago Professor Hallin worked at the Sudbury Neutrino Observatory, and in 2015 the team on which he worked was honored with a Nobel Prize in physics.

So yeah, there we have at least one contribution that a non-humanist has made to science.

Which leads me to ask, what contributions has our humanist narrator, Mr. Stephen Fry, made to scientific knowledge? Hmm, I’m not sure. His Wikipedia profile describes him as a “comedian, actor, writer, presenter and activist.” But it doesn’t mention any Nobel prizes in science. In fact, it doesn’t mention any formal contributions to science at all. Which seems a bit ironic given that he claims this is the one way to know about the world. (Oh, and in case you were wondering, the answer is sadly no, propaganda humanist videos do not count as contributions to science.)

Now here’s an interesting question: do humanists also partake of forms of knowing apart from the empirical study of science that is rooted in sense perception?

The answer is yes, of course. Let’s name a few. Consider rational intuition, the means by which one intuits what philosophers refer to as synthetic a priori knowledge. (See, for example, Laurence BonJour’s book In Defense of Pure Reason (Cambridge University Press, 1998.) If you want a stunning example of pure reason then read the life story of the great autodidact mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan. Or consider moral intuition/moral perception, the means by which one initially appraises the moral status of actions and states of affairs. And then there is the ability to intuit danger. And proprioception, our ability to know where our body is extended in space. And memory, our ability to recall the past. And testimony.

Alas there are more ways to gain knowledge of the world, Mr. Fry, than are dreamt of in your reductive empiricist philosophy.

To conclude…

Imagine if a Christian apologetics and evangelism organization produced a two-minute video which contrasted the “God-fearers” and the “atheists”. The narrator waxes ominously, noting that while the God-fearers embrace meaning, purpose, and morality, the atheists embrace a bleak vision, reducing human beings to mere “machines made of mud.”

No doubt Mr. Fry and the British Humanists Association would be utterly indignant. Propaganda! they’d cry. Indoctrination! And they’d be right. Such a video would be propaganda, it would be promoting indoctrination, and it would deserve an indignant reprimand.

The binary opposition in this video is no less stark and the caricature of the out-group no less appalling. It is nothing more than propaganda that seeks to subvert proper reasoning in favor of furthering an ideological agenda.

The post How the British Humanist Association Promotes Propaganda appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 9, 2016

Is there a better way to know than science?

A reader named “Oliver” posted the following questions in the thread to my article: “How the British Humanist Association undermines Humanism“:

“Is there a better, more reliable, way of knowing what is and isn’t true than the scientific method? If so, can you describe it?”

The first, relatively minor problem with the question is that there is no single scientific method. Or, at the very least, there is no agreement among scientists and philosophers of science that there is. Consider, for example, this excerpt from the entry on “Scientific Method” in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

The issue which has shaped debates over scientific method the most in the last half century is the question of how pluralist do we need to be about method? Unificationists continue to hold out for one method essential to science; nihilism is a form of radical pluralism, which considers the effectiveness of any methodological prescription to be so context sensitive as to render it not explanatory on its own. Some middle degree of pluralism regarding the methods embodied in scientific practice seems appropriate. But the details of scientific practice vary with time and place, from institution to institution, across scientists and their subjects of investigation.

We can address that minor issue by rephrasing the question as one regarding scientific methods. But that brings us to the bigger problem with the question: whether we speak of method (singular) or methods (plural), the question is still wrong-headed. Let’s start by restating the slightly amended question:

“Is there a better, more reliable, way of knowing what is and isn’t true than the scientific methods? If so, can you describe it?”

And my question in return is, better or more reliable for what? How about getting directions to that Italian restaurant you’re eating at tonight? Are you going to use scientific methods for that? How about knowing that your spouse really loves you? What about knowing that a life spent helping the poor is morally better than a life murdering them and stocking them in your basement freezer? What about knowledge of who won the 1952 World Series? Or knowledge that you’re not just a brain in a vat?

The fact is that just as there are many scientific ways to gain knowledge of the world, so also there are many non-scientific ways to gain knowledge of the world. Scientific methods have proven an enormously productive tool for gaining knowledge of the structure, processes, laws, and forces of nature. But it would be a whopping non sequitur to conclude from that fact that science provides the single preferred way to gain knowledge about anything.

For further discussion see my book The Swedish Atheist, the Scuba Diver, and Other Apologetic Rabbit Trails, chapter 15, “Naturalism, Scientism and the Screwdriver that could fix almost anything.”

The post Is there a better way to know than science? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 8, 2016

How the British Humanist Association undermines Humanism

The Atheist Missionary tweeted me a link to a short video produced by the British Humanist Association (BHA) with the comment: “A short informative video on humanism for your seminary students”.

Here it is. It’s only two minutes so give it a go before you continue with the article…

I had two initial reactions. I will devote this article to the first reaction and a second article to the deeper (and more problematic) reaction.

So to begin with, the first reaction was initially a general puzzlement since the video, which ends with the declaration “this is humanism!” is not, in fact, concerned with humanism per se. Rather, it is concerned with epistemology, and more specifically with what appears to be a tacit endorsement of scientism. This much is evident from the fact that the video answers the question “How do we know what is true?” by invoking the methods of science.

While I was initially perplexed that the video would seem to equate humanism with scientism, a quick check online revealed that this video is one in a series of “That’s humanism!” videos, each of which is intended to address one aspect of what the BHA apparently believes to be elements in a humanist worldview. So at least that made some more sense: the BHA believes that humanism includes a commitment to scientism.

But at that point my puzzlement shifted to surprise and amusement that this video presents a self-defeating account of humanism. Let me explain.

Consider that scientific knowledge produces descriptive facts, i.e. facts about natural structures, processes, and laws. What science doesn’t give us is value facts, i.e. facts concerning what ought to be valued. And yet, humanism is predicated on value facts, i.e. the fact that the human species is valuable and the flourishing of human beings collectively ought to be valued by individual human beings.

As a result, if we accept the BHA’s endorsement of scientism, then our knowledge is limited to descriptive facts, a consequence that undermines our ability to know the very value facts that under-gird any commitment to humanism. In other words, the BHA has produced an account of humanism that undermines any rational ground to assent to the truth of humanism, and it did this in just over two minutes. That’s quite an accomplishment! I always appreciate it when atheists and humanists generously help the Christian apologist by taking the time to refute their own views.

September 6, 2016

Do Calvinists and Arminians worship the same God?

We’re going to address Calvinists and Arminians in a moment. But first let’s begin with the catalyst for the discussion which is a February 2016 episode of William Lane Craig’s venerable Reasonable Faith Podcast titled “Do Christians and Muslims worship the same God?” In this podcast Craig addresses the controversial question that was first raised as a result of a Facebook post by Professor Larycia Hawkins of Wheaton College when she opined that Christians and Muslims worship the same God. Hawkins’ early December post spawned a flurry of debate on the internet.

Craig’s Argument

In this episode of the podcast Craig interacts with an article by Francis Beckwith. Beckwith begins by noting that the topic here is reference: when Christians say “Yahweh” and Muslims say “Allah” do they refer to the same being? Beckwith argues that they do. But Craig thinks otherwise. In his view, the concepts of deity in Christianity and Islam are so different that Craig believes Christians and Muslims do not refer to the same being. Here is a key clip approximately 18 minutes into the podcast which nicely states Craig’s view:

http://randalrauser.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Craig-on-Islam-and-God.mp3

To sum up, Craig argues that Christian and Muslim concepts of God are so different that Christians and Muslims refer to different entities altogether when they use the term “God” (or, as noted above, when Christians refer to “God” or “Yahweh” and Muslims refer to “Allah”).

Craig identifies two points of doctrinal difference to justify this conclusion: the doctrine of the Trinity and the attribute of perfect love. Importantly, Craig views each of these two points of doctrinal divergence as sufficient to secure the conclusion that Christians and Muslims refer to different entities when they refer to God. Given that fact, we will proceed for the rest of this article by focusing on disagreement on the latter attribute of God’s love.

With that in mind, we can now turn to the second point, that which Craig refers to as “the moral character of God.” Craig opines that the Muslim concept of God is “morally defective”. Why? Craig explains that according to Islam “God is not an all-loving being; he loves conditionally only those who first love him, say the confession and do the alms, do the prayers.”

According to Craig’s view, Christians believe that God exemplifies a property of perfect love. For our purposes, we can define that attribute relative to its human subjects as follows:

Perfect love: the property by which God loves all people equally and irrespective of any merit in the individual.

However, Muslims deny perfect love on two points: (1) while Christians believe God loves all people equally, Muslims believe God loves Muslims but does not love non-Muslims; (2) while Christians believe God’s love is extended irrespective of any merit in the individual, Muslims believe God’s love is extended based on the meritorious actions of devout Muslims (e.g. saying the confession, doing alms, etc.).

Different entities or disagreement about the same entity?

Let’s grant that this difference exists between (Christian) perfect love and (Muslim) imperfect love. Even so, it isn’t clear that this difference is sufficient to support the conclusion that Christians and Muslims are referring to different divine persons.

Consider, Ivanka Trump and Keith Olbermann can both refer to Donald Trump despite the fact that they differ radically on their assessment of his character: Ivanka thinks The Donald is a loving man while Olbermann thinks he is a psychopath who presumably lacks the ability to love anybody. Here’s the most critical point: nobody supposes that this divergence justifies the conclusion that Ivanka and Olbermann are referring to different entities. Indeed, if we did conclude that then it would follow that Ivanka and Olbermann do not disagree about The Donald. But of course they do disagree.

By the same token, if Christians and Muslims are not referring to the same being — God — then it follows that they do not disagree about the attribute of God’s love. But this seems to me a very strange read of the situation. Far more plausible, I would think, to conclude that just as Ivanka and Olbermann are referring to (and disagree about) the same New York business mogul, so Christians and Muslims are referring to (and disagree about) the very same God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob.

Calvinists and Arminians

Now let’s turn to the question for which this article is titled: “Do Calvinists and Arminians worship the same God?” Remember that Craig apparently takes the view that the Muslim’s failure to affirm that God exemplifies perfect love is sufficient to deny that Christians and Muslims refer to the same being when they refer to God.

The problem is that mainstream Calvinism also denies that God exemplifies perfect love (as defined). Instead, Calvinists affirm that God has a general love for all creatures but he has a special love for the elect, and it is this love which is a basis of their election.

Arminians have not been shy about denouncing the Calvinist denial of perfect love. When I interviewed Roger Olson a couple years ago he referred to God in Calvinist theology as a “monster”. And he isn’t alone in that assessment. John Wesley stated that the Calvinist doctrine presents a picture of God as “worse than the devil; more false, more cruel, and more unjust.”(Cited in Jerry L. Walls, “Divine Commands, Predestination, and Moral Intuition,” in The Grace of God, the Will of Man: A Case for Arminianism, ed. Clark Pinnock (Grand Rapids, MI: Academie, 1989), 266.)

Calvinists, for their part, have not been shy to return the favor by lobbing equally incendiary denunciations back at the Arminian conception of God as an impotent weakling who can’t really save anybody until they decide they want to be saved.

What about the fact that, as Craig says, God’s love is conditional according to Islam? The point Craig misses here is that in mainstream Muslim theology the elect are determined to act (e.g. say the confession, do the alms, do the prayers) by God’s sovereign will. And that parallels closely the Calvinist view that the elect are determined to act (e.g. say the sinner’s prayer, persevere in faith, produce fruits) by God’s sovereign will. Consequently the difference on the divine love that Craig envisions between Christianity and Islam closely parallels the difference between Arminianism and Calvinism.

To sum up, if disagreement regarding the attribute of perfect love is sufficient to conclude that Christians and Muslims refer to (and so worship) different gods, then it is sufficient to conclude that Calvinists and Arminians refer to (and so worship) different gods. I will leave it to the reader to consider whether this conclusion meets the demands of a reductio ad absurdum for Craig’s position.

September 3, 2016

The Irony of the Critique: A Response to Richard Carrier

Recently Richard Carrier reviewed my book Is the Atheist My Neighbor? Let’s start with the good news: Carrier liked the book which he described as “packed full of facts and arguments” and a “brief but thorough and well-studied book”. (That’s two fine endorsements for the back cover of the second edition which will never be printed due to lack of demand.)

That said, reading accolades is like eating candy: enjoyable but not very nourishing. All the protein, fiber, and antioxidants are found in chewing on the criticisms. With that in mind, I’m going to bypass the positive first part of the review for the critical second part which Carrier devotes to a “Survey of Qualms”. Carrier does not hold back in his qualms, so I won’t hold back in my rebuttal. I have divided my critical response into four parts to parallel the four main qualms that Carrier raises.

One more thing: before we jump in, let me underscore that I really enjoyed this stimulating and provocative review and I am grateful to Carrier for the effort he put into such a careful and extensive critical engagement.

The Rhetorical Force and Function of Anti-Atheist Memes

In the book I argue that Christians often have a prejudicial hostility toward the atheist outgroup. Carrier does not dispute the point, but he does believe I’ve missed an important dimension of these anti-atheist memes:

“While Rauser wants to call Christians to task for bigotry, and that’s indeed a worthy point, I think we also need to be calling Christians out for something that’s more sinister here: these memes exist in a matrix of control doctrines designed to scare Christians away from even contemplating, much less accepting nagging doubts. Repeating these memes, and checking to see who laughs at them or assents to them, is intended as a threat—not to atheists, but to fellow Christians. There are countless analogs in other social movements, where certain memes are designed to shut down questioning and shore-up a feeling of in-group superiority that aims to prevent or discourage insiders from even contemplating agreeing with outsiders, much less leaving the in-group to join them.”

Later Carrier explains further:

“Their function is not conversion, but defense against defection. And the more you see Christians doing this, the more they are retooling their religion into a cult.”

I agree that the anti-atheist memes can have this kind of indoctrinational function. I never suggested otherwise. In fact, I addressed this topic previously in my 2011 book You’re not as Crazy as I Think (see chapter four, “Not everything is black and white”). However, when I addressed the problem of indoctrination (i.e. what Carrier dramatically describes as a “cult”) within Christian communities, I pointed out that it also arises within atheist communities. The more that atheists denounce religious believers as irrational “faithheads”, the more they question the emotional stability of the religious, the more they accuse them of retaining an infantilized belief of childhood, the more they are retooling their irreligion into a cult. I am of the opinion that when you identify this problem in an outgroup, you should devote equal time to identifying it within your particular ingroup.

As for Carrier’s claim that I should have analyzed the way anti-atheist rhetoric serves an indoctrinational function in the present book, well, maybe. There’s always more one can include in a book. But I don’t agree that the book’s force is critically weakened by the absence of this material, nor has the feedback I’ve received from others supported that conclusion.

Conveniently reinterpreting the Bible?

Next, Carrier suggests that I engage in an overly fanciful and arbitrary reading of the Bible. There is some thought-provoking commentary here, but I’m going to skip to the essence of the charge:

“Rauser still builds a good contextual case for his reading that’s worth considering. But there is a reason Hector Avalos lambastes these kinds of exegetical tricks in The End of Biblical Studies. They are often aimed at “saving” the Bible, from being the vomit of primitive and savage minds, by turning it into some sort of miraculously prescient treatise on 20th century science and logic that it’s not. As a matter of historical fact, the Bible wasn’t written by people that well informed or that wise or that nice. And we have to interpret it realistically accordingly.”

Carrier is apparently drawing a contrast here between Christians who engage in “exegetical tricks” to “save” the Bible and those more sober-minded, objective critics like Avalos and Carrier himself who instead “interpret it realistically”.

I question the contrast. Let’s start with the fact that Carrier chooses to refer to the Bible as “the vomit of primitive and savage minds”. Does that sound like the language of a dispassionate and wholly objective critic with no personal investment?

Let me be blunt: If I read the Bible as an orthodox Christian with the interest of “saving” it, the evidence suggests that Carrier reads the Bible as an atheistic skeptic with the interest of “damning” it … or at least damning Christian readings of it. Put another way, Carrier and I both have a particular way of reading the Bible that we’re interested in saving … and competing readings that we’re keen to damn.

Moreover, if my orthodox-friendly readings of the Bible attract their share of criticism, the same can surely be said for Carrier’s own mythicist reading of the New Testament. Which reminds me of the old saying: he who lives in a glass house shouldn’t throw stones.

Don’t get me wrong: Carrier has every right to approach the Bible with a particular set of presuppositions and to develop and defend a particular reading of the text based on those presuppositions. But believe it or not, the same courtesy that is enjoyed by the atheistic mythicist is also extended to the orthodox Christian.

Atheism in the ancient world

Carrier’s third qualm concerns a historical matter: he challenges my claim that atheism (as it is understood today) is a modern phenomenon. He cites several putative examples of atheism in the ancient world and he also refers to Tim Whitmarsh’s book Battling the Gods: Atheism in the Ancient World (a book that, by the way, was published after my book was released so I did not have the benefit of reading it).

This is an interesting and complicated topic. Unfortunately, I haven’t yet read Whitmarsh’s book so I won’t comment on his argument. However, I will reiterate a point I made in the book that we need to be careful about reading later concepts of atheism or theism back into earlier uses of the term. Just because a person affirms (or denies) belief in an entity called “God” does not automatically qualify her as a theist (or atheist). One must also consider the various concepts of God at play to know what exactly is being affirmed (or denied).

Which God?

Next Carrier addresses what he calls “The problem of which God.” He begins:

“Rauser struggles to both explain the intelligibility and reasonableness of the modern atheist rejection of God on the basis of arguments from evil, and at the same time not admit that the argument is correct.”

Um, no, I don’t “struggle.” I’m perfectly comfortable recognizing that rational people can defend reasonable arguments for opposing conclusions. In fact, I believe it is just good scholarly practice (as well as neighborly charity) to seek to present the strongest versions of your opponent’s argument. And I’ve done that in the past with atheism and the problem of evil. (See, for example, my book You’re not as Crazy as I Think, 47-50.)

I’m going to cite the next paragraph in its entirety and then respond to a couple different points raised therein:

“Here he almost but doesn’t quite work out that contextually we aren’t talking about just any God; that as far as generic gods go, Rauser himself has no belief in them and would be an atheist himself, were they the only thing on offer. For example, in his admirably sympathetic treatment of Hitchens (and his famous treatment of God as a monster we ought to rebel against rather than worship), I don’t think Rauser makes clear enough that Hitchens is not arguing against or ever even talking about “just any god,” but specifically a God who is claimed to be morally admirable, after in turn looking at the evidence before our eyes. Once you limit the conversation to that specific kind of God, theodicy is a universal acid. There is no empirical room left for any god like that. Instead, the sort of God who would allow the things that happen in this world, must necessarily be the most horrible person imaginable (a fact Rauser does eloquently describe and explain, so he definitely gets this much).”

Let’s consider Carrier’s claim that the “empirical” evidence of evil entails that “necessarily” God (if he exists) is “the most horrible person imaginable” (i.e. that which none worse can be conceived).

To begin with, this statement overlooks the fact that the definition of God I use in the book includes the property of perfect goodness. It is incoherent to say that an entity could simultaneously exemplify the properties of perfect goodness and perfect horribleness. Thus, if God, as defined, exists then it follows that God has a morally sufficient reason to allow the evils that do occur.

This brings me to the second point. Has Carrier demonstrated that the empirical evidence necessarily precludes the existence of God? No, this is nothing more than a bald assertion. Carrier simply assumes, without argument, that God could not have morally sufficient reasons for allowing evil in the world. Consider the following two propositions:

(1) Richard can see that God cannot have morally sufficient reasons for allowing the evils we observe.

(2) Richard cannot see that God can have morally sufficient reasons for allowing the evils we observe.

Richard accepts (1) and I accept (2). If he wants to present a defeater to God’s existence, if he wants to persuade me of (1), he needs to work his intuition — an intuition that I do not share — into an argument that can persuade a skeptic like myself. And I should add that I’m not the only one who is a skeptic of Carrier’s intuition. His intuition is not widely shared among academic philosophers of religion (including atheist philosophers of religion). This is important given that these are the people most familiar with the subject matter.

Carrier continues:

“That is why atheists say God is a horrible person: not because they think there is a God or because they wish to insult the Christian construct of God or because “they just want to sin” or are just “rebellious” or whatever, but because that horrid God is the only kind of God compatible with the evidence; and surely no one, not even the Christian, should wish such a God would exist, nor praise it.”

Once again, Carrier has provided no argument to show that the existence of evil negates the existence of God. He simply asserts it. Such declarations may fly with the Carrierites, but they are woefully underwhelming to those not predisposed to defer to Carrier’s opinions.

Note as well that while Carrier opines that atheists generally reject God as “a horrible person”, that is not true of Jeff Lowder, the atheist that I interview in the book. Nor is it true of many other atheists I know. It is unfortunate that Carrier doesn’t acknowledge the many atheists like Lowder who reject his reasoning.

Later in his review, Carrier makes a comment about Christopher Hitchens:

“Certainly, atheists would be delighted to discover a God existed who was actually a supremely moral person, someone who was always honest and compassionate and never abandoned or betrayed or tortured anyone and always helped everyone. But that’s not the God atheists like Hitchens were ever talking about when they spoke of rejecting God.”

While this is a relatively minor point, I should note that this is not how I read Hitchens. On my reading, he doesn’t simply object to the idea of God as a tyrant who does terrible things to hapless creatures. Hitchens also rejects the mere notion of an omniscient being, a state of affairs which he decries as tantamount to living in a celestial North Korea.

Carrier then continues with his rhetorical broadside:

“That is not the God Christians like Rauser claim exists. It is not the God they want there to be. But it is, alas, the only God there can be. Unless you intend to insist no children were ever raped, that they were all mindless holograms placed on earth to test the flock. Otherwise, you have no logical option left: your God is okay with mass child rape. And such a God is simply depraved. And only the depraved would worship so depraved a God as that. Rauser gives the usual apologetic reply that there could still be some logically possible reason unknown to us that, were we to discover it, we would understand it wasn’t depraved, that allowing the mass rape of children was actually the best thing ever. But that’s not even remotely probable. It is, in fact, even more ridiculous than my mindless hologram theory. Because we know how to make better worlds without the mass rape of children. And surely we can’t be better at this than God. Rauser means well. But he isn’t seeing the truth here.”

I’m going to wrap up my critical rejoinder by noting three things from this passage.

First, Carrier continues to rattle his saber with a healthy dose of rhetorical bluster on the problem of evil. For example, he opines that the only “logical option left” for the theist is that “God is okay with mass child rape”. Note how Carrier chooses to level his charge with the hopelessly imprecise and ambiguous word “okay”. What does he mean by saying God is “okay” with “child rape”? Does he mean to say God likes child rape? That God approves of child rape? Or merely that God permits child rape for some reason? Such ambiguous and imprecise phrasing of a charge is quite out of place in serious philosophical analysis, all the more so when the topic being discussed is highly emotional.

Second, I need to highlight Carrier’s comment on the morality of theists. As he puts it, “such a God is simply depraved. And only the depraved would worship so depraved a God as that.” (emphasis added) Did you get that? Apparently theists are “depraved”. I wrote a book critiquing Christians for launching broadside moral indictments of atheists, and now an atheist reviewing the book returns the favor by launching a broadside moral indictment of Christians.

And this brings me to the third and final point. Not only are Christians “depraved”, but in Carrier’s estimation we are clearly also irrational. He’s already suggested as much in his claim that any God would necessarily be “horrible”. Consider as well how Carrier dismisses my brief treatment of theodicy in the book as “ridiculous” and “not even remotely probable”. (Don’t hold back Richard. Tell me what you really think!) Once again, this amounts to nothing more than Carrier sharing his personal opinions. By that standard, all parties to the discussion can win by just labeling the views of their interlocutors as ridiculous. And what’s next? Yo momma jokes?

Conclusion

To sum up, I wrote a book criticizing Christians for dismissing atheists as depraved and irrational. And that book has now been critiqued by an atheist who believes that Christians are depraved and irrational. But the irony doesn’t stop there. Remember that in his first objection Carrier worried that the rhetorical denunciation of atheists as immoral and irrational left Christians in danger of “retooling their religion into a cult.” So what, do you suppose, is the effect of Carrier’s rhetorical denunciation of the Christian?

August 31, 2016

The Imprecatory Psalms at Daylight Church

June 2016 talk at Daylight Church

06-05-16 – I Object – Part 5 – Guest Speaker Randal Rauser – The Imprecatory Psalms from Daylight Church on Vimeo.

How to Hate Your Enemies: A Sermon

I’ve preached and spoken on the imprecatory psalms on several occasions. This past Sunday I preached my latest sermon on the topic, and it represents a further development in my thinking on the curses in the psalms and how best to appropriate them. The recording misses the first couple minutes of the sermon.

http://randalrauser.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/160828_RandalRauser_HowToHateYourEnemies.mp3

August 30, 2016

No, he didn’t think of you “above all”: Or, the hubris of popular Christian piety

There is a curious narcissism that infects popular piety today which would have it that you (or I) are (or am) somehow the fulcrum of God’s universe. It’s really all about you (or me).

As the story goes, God created the universe just to be with you. Apparently God is like Dusty Springfield singing “I only want to be with you.”

And when Jesus was dying on the cross, of all the thoughts crowding his agonized mind, it turns out that you topped them all:

I hate to be the bearer of bad news but the fact is that Jesus speaks seven final words from the cross, and neither of us is mentioned in any of them. (Shocking, I know!)

Instead, he offers forgiveness for his tormentors, the promise of redemption for a thief, directions for his mother and a close disciple, two words to his Father, a declaration of thirst, and a final statement: “It is finished”.

You might reply: he could still be thinking about us even if he didn’t mention us!

True enough. But I’m guessing in the midst of the agony of dying that he didn’t have much headspace left to ponder my winsome smile or your dazzling eyes.

And what about the notion that God created the universe just to be with me and you? Look, I admit that we’re both fine specimens, but don’t you think that’s a bit much? After all, there are billions of human beings and trillions of other animals on our planet. And there could be countless advanced technological civilizations in this universe of 130 billion galaxies.

When you add into the mix this thing about God acting for his own inscrutable glory, that declaration about God’s singular creative intent seems like hubris run amok.

While I haven’t always found myself in agreement with Rick Warren, I’ve always appreciated the way he started The Purpose Driven Life: “It’s not about you.”