Randal Rauser's Blog, page 142

September 19, 2016

That’s Why We Love Unbelievable: Two impressive moments from the latest show

In this unique American election season I’ve spent far too much time watching partisan pundits on cable news. One thing you are unlikely ever to hear from a Clinton or Trump supporter: “If I’m wrong, I want to know. ” Still less: “After examining the evidence I have changed my views to be less partisan in support of my candidate.” Instead, the two sides quickly line up against one another and open fire with the host left to run for cover.

Compare that with the most recent episode of Unbelievable in which Christian apologist Jeff Zweerink and atheist Skydive Phil have an open and honest discussion on the multiverse. This is Unbelievable at its best with both Zweerink and Skydive Phil exemplifying a refreshingly non-partisan, open discussion on possible evidence for the multiverse, and the implications it might have for alleged cosmic fine-tuning. While the entire show is worth a listen, two moments stand out for me as especially revealing for the way they exemplify the spirit of Unbelievable.

The first moment comes 32 minutes into the show. To set up the context, the very intelligent, informed, and articulate Skydive Phil has claimed that there is scientific evidence for the multiverse. However, in a recently produced (and excellent) short video Brierley claimed that there isn’t scientific evidence for a multiverse.

So what do you think most folks would do if they were in Brierley’s shoes? What would most do if they’d just produced a professional video in which they made a claim that was now being challenged by a guest who was intelligent, informed, and articulate? Simple: they’d sit quietly until the storm had passed. Or, to shift metaphors, they’d deftly guide the interview through the mine-field. Or, as folks are wont to say in the current American election cycle: they’d pivot.

Not Brierley. Instead, he addresses the elephant in the room. Or, to shift metaphors again, he takes the bull by the horns and plays a clip from his video in which he makes the very claim under contention. Then he comments:

http://randalrauser.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Multiverse-1.mp3

Give the man credit. That is what it looks like to place a concern for truth over partisanship or personal reputation or a professionally produced video. We should all aspire to this level of open and vulnerable discussion.

And that brings me to the second point which comes 36 minutes into the show. In this clip Brierley asks Zweerink whether the multiverse does damage to claims to cosmic fine-tuning. Zweerink’s honest and vulnerable evaluation of the situation is disarming and most certainly not the norm in the typically partisan and heated atheist/Christian debates:

http://randalrauser.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Multiverse-2.mp3

Zweerink is a research scholar with Hugh Ross’s organization Reasons to Believe. While I certainly respect Hugh Ross as one of the smartest (and nicest) people in Christian apologetics, Ross also tends to reflect a triumphalism about the scientific evidence for Christianity.

While I don’t mean to pit Zweerink against Ross, I will say that Zweerink’s modest admission of the points where the available evidence is not a boon for the Christian is an essential part of a credible apologetic in the contemporary world. The lesson, I would submit, is that apologists on all sides should recognize when the evidence doesn’t favor their position, not least because it’s the right thing to do. What is more, in the long run being honest actually serves one’s interests as an apologist in search of a winsome and effective presentation of their views.

I illustrate the latter point in my book You’re not as Crazy as I Think with an analogy drawn from Miracle on 34th Street. The problem starts when Kris Kringle, the Macy’s Santa, starts telling customers when Gimbel’s has a lower price on a particular toy. As soon as the manager hears of this he is outraged and plans to fire Kringle. What kind of employee would cede a sale to their competitor? What the manager didn’t anticipate is that Kringle’s honesty leads the customers to become more loyal to Macy’s because they recognize that here is a retailer who is more interested in serving the customer rather than merely making the sale.

It’s worth underscoring the first point again: whether you win a customer or not, it’s still the right thing to do. At the same time, in this world of perpetual partisanship and ceaseless spin-doctoring, honesty has its own rewards just the same, and you may well find that losing an argument wins you respect … and perhaps even a convert.

All that is to say that these are two refreshing examples of why we love Unbelievable.

The post That’s Why We Love Unbelievable: Two impressive moments from the latest show appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 18, 2016

Christian apologists need to lead by example and stop caricaturing their opponents

Let’s begin with a tweet from Christian apologist Andy Bannister:

Andy’s a great guy and I very much enjoyed meeting him this past spring and doing several interviews/events with him (including our Islam discussion on Bold Cup of Coffee, my interview on Bold Cup with Andy on his book, his debate/dialogue on Islam that I moderated, and his appearance on my podcast).

However, tweets like this just aren’t helpful! Christian apologists shouldn’t misrepresent and strawman the views of their intellectual opponents, and this tweet does both.

First off, atheism isn’t a worldview, it’s a denial of the existence of God which can be part of many different worldviews.

Second, piling up negative adjectives and polemical descriptions merely invites an equivalent reply. Does Andy want atheists to treat Christianity like this?

“Christianity is an empty, sterile worldview, that makes us pawns of a capricious tyrant who will damn many of us in eternal fire for his glory.”

Is this the description of Christianity that Christian apologists want atheists to be tweeting? Presumably not.

But then Christian apologists need to lead by example by representing the views of their opponents with charity and nuance. Consistently following the golden rule of hospitable dialogue with those with whom you disagree is the first step in presenting a credible apologetic to a skeptical world.

The post Christian apologists need to lead by example and stop caricaturing their opponents appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 17, 2016

Sports, violence, and irrational secularists

Let’s approach the matter of religion and violence from a slightly different angle.

I lived in London, England for a couple years. One day I was strolling down the sidewalk when I noticed the street had been blocked off at an intersection and a couple dozen bobbies were standing around nervously. Curious, I went up to one of them and asked, “What’s going on? Has there been an incident?”

“Not yet,” the officer replied omniously. He then explained the problem. Currently a football match was being played in greater London between football clubs that had a long and often violent rivalry. And as luck (or fate?) would have it, fans of the two clubs were centered at two pubs that were kitty-corner to each other at this intersection. In the past whenever these two teams would play each other, the fans had a habit of spilling out of the pubs after the game and rioting in the street. And so the police had taken to preemptive actions to prevent any eruption of violence.

While it was a bit of a culture shock, I soon grew accustomed to the violence that sometimes comes with English soccer fans.

Now imagine somebody citing scattered examples like this to justify the conclusion that the world would be less violent without sports … and so we’d be better off without sports. Such a bald claim wouldn’t even get the time of day. People who made it would be laughed out of the room. And along with the laughter would come a string of incredulous rejoinders:

You think all sports are linked to violence? MMA and boxing, perhaps. But tennis? Golf? Chess?

What makes you think it is sports per se that is the catalyst for violence? Isn’t it the case that social groups all specialize in making and sustaining in group/out group distinctions? You see the same phenomenon in politics and philosophy, culture and religion. So why pick on sports?

And even if it were true that sports on the whole increased violence in society, you can’t make any judgments about the social value of sports until you add up all the goods that sports also produces. What about the value of physical fitness? Social cohesion? The virtues of courage and self-discipline? Mental engagement?

The bottom line: it would take a truly irrational prejudice against sports to float with any seriousness the thesis that sports on the whole increases violence and so we’d be better off without sports.

And yet, throw a Nerf football into a crowd at a “skeptics” convention and you’ll probably hit a couple people that argue a claim no less absurd about “religion”. How ironic that folks who pride themselves on their cool minded rationality harbor an irrational prejudice of such formidable proportion.

The post Sports, violence, and irrational secularists appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 16, 2016

Does religion cause violence?

A commenter named Logic Ninja just posted a comment that made a couple points in the discussion thread to my article “Haha. Imagine that.” The second point concerned the linking of religion and violence. Logic Ninja wrote:

“If there were no religion, do you think there’d be MORE war, or LESS? If you answered “more,” I can recommend a good remedial history course in your area. If you answered “less,” then what the hell’s your point in the second paragraph?”

Interestingly, I’ve been teaching graduate level history courses (in my area) for more than ten years, so there is a certain irony with an anonymous commenter condescendingly suggesting that I take a “good remedial history course”. Haha. Imagine that.

But more to the point, I replied as follows:

“if there were no pacifistic Quakers and many more secular Neo-cons, do you think there’s be MORE war, or LESS?”

Hopefully Logic Ninja will get the point. If not, I’m happy to spell it out here. The statement “Religion causes violence” is about as meaningful as the statement “Eating causes cancer.” The threat of violence depends on the religion you’re practicing as surely as the threat of cancer depends on the food you’re eating.

To be frank, I would have thought that point to be rather obvious. But then, blinding anti-religious sentiments have a way of obscuring the obvious.

The post Does religion cause violence? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

The Fallacy of Charitable Interpretation

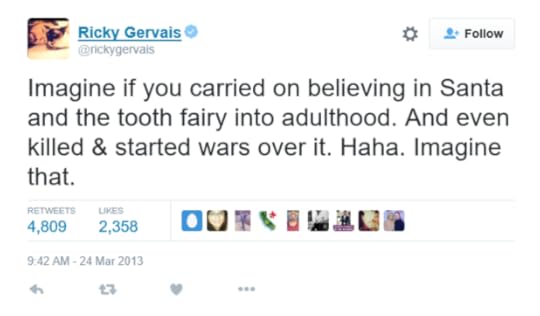

In my article “Haha. Imagine that.” I offered a rejoinder to the following Ricky Gervais tweet:

“Imagine if you carried on believing in Santa and the tooth fairy into adulthood. And even killed & started wars over it. Haha. Imagine that.”

In the discussion thread, Logical Question then offered the following response:

“Viewing Gervais’s tweet sympathetically, he may not have been thinking about a purely philosophical belief in God with no specific threats of hell for those who “blaspheme” such a God, and no specific threats aimed at those who dare to commit “heresies” by holding doctrinal views that differ from “orthodoxy,” i.e., more specific views of God rather than less specific ones. The more specific ones have had kings and kingdoms “defending” them from other kings and kingdoms.”

I’m not going to go into the weeds with the substance of this tweet, except to note that Logical Question makes some substantial assumptions in his quest for a “sympathetic” interpretation.

What I do want to do here is warn against what I call the charitable interpretation fallacy. The fallacy results from a misreading of a common philosophical principle called the principle of charity. According to the principle of charity, you ought to interpret others in a way that maximizes the truth or rationality of their utterances. Applied to the present circumstance, so the reasoning goes, when I encounter a tweet that seems crassly reductionistic in its understanding of and engagement with religion, I ought to interpret it in a way that redeems the tweet. And so we get our various proposed sympathetic interpretations.

The problem with that approach is that the principle of charity is a ceteris paribus (i.e. other things being equal) principle. It is not an absolute. And that make all the difference. Consequently, one commits the charitable interpretation fallacy when they disregard relevant background material (i.e. they fail to recognize that all is not equal) in seeking a charitable interpretation.

To consider our present case, if I knew absolutely nothing of Ricky Gervais and had no context for the original posting of his tweet, I might have cause to seek a charitable interpretation of it. But I am familiar with Gervais’ withering anti-religious views: he is, in short, the Court Jester in the new atheist kingdom. That is not to say I dislike his comedy. On the contrary, I’m a huge fan of The Office and Extras (but alas, not Derek). But it does mean that I know enough not to expect subtlety, nuance, or charity when I encounter Gervais’ tweets on matters of religion. So neither should I extend charity when interpreting them.

The post The Fallacy of Charitable Interpretation appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 15, 2016

Haha. Imagine that.

Ahem,

Imagine if you caricatured a complex religious worldview you reject which claims billions of adherents from all cultures, socio-economic backgrounds, and educational levels, by comparing it to an infantilized belief of childhood.

And then you went on to ignore all the complex cultural, socio-economic, political, and religious factors that lead to societal violence and war by suggesting the single cause was disagreement over doctrines within that complex religious worldview.

Haha. Imagine that.

The post Haha. Imagine that. appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 14, 2016

Jesus meets Mike Pence

“Then he will say to those on his left, ‘Depart from me, you who are cursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels. For I was hungry and you gave me nothing to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me nothing to drink, I was a stranger and you did not invite me in, I needed clothes and you did not clothe me, I was sick and in prison and you did not look after me.’

“Then Mike Pence will answer, ‘Let me guess, this is about the time I ordered state agencies in Indiana not to help Syrian refugees, right? You’re not going to listen to the liberal courts, are you Lord? I know they said my directive was discriminatory, but look, Lord, they weren’t properly screened. They could’ve been terrorists, after all.'”

The post Jesus meets Mike Pence appeared first on Randal Rauser.

Goddidit and Golden Hammers

It’s been awhile since I commented on that favorite atheist quip intended to shut down any explanatory appeal to God: “Goddidit”.

It’s been awhile since I commented on that favorite atheist quip intended to shut down any explanatory appeal to God: “Goddidit”.

Want to argue that God is the best explanation of cosmic fine-tuning? The origin of the universe? Moral obligation? Truth-directed cognitive faculties? You can shut ’em all down with one three syllable word-phrase:

Goddidit!

Defining Goddidit

Here is how the online Urban Dictionary defines the term:

“Contraction of ‘god did it’, a sarcastic term to show that the explanation for something is based on religious belief, and not sound arguments.

“Much used for arguments presented by IDiots and other religious bigots who are too lazy, or too stupid, or too dishonest to acknowledge that there are proper scientific explanations for most things.

“It is in particular used to explain ‘irreducible complexity’, a vague term used by IDiots to prove that god created the Universe.”

According to the Rational Wiki website, “Goddidit” is an example of a more general informal fallacy … the “Didit fallacy”:

“A didit fallacy is an informal fallacy that occurs when a complex problem is handwaved away by invoking (without reason) the intervention of some powerful entity.

“All didit fallacies are essentially golden hammers, because they propose a simplistic solution for a range of complex and unrelated problems.”

Later in the article we encounter a list of sample Goddidit indiscretions including the following:

There are a few small gaps in most fossil records linking one species to another. God did it!

No one knows what is the (if there is any) carrier force of gravity. God did it!

Love is a strong and mysterious emotion. God did it!

The universe appears rather fine-tuned for life on earth. God did it!

We cannot explain how memory works. God did it!

This chicken mayonnaise sandwich is delicious. God did it

I agree with the Didit fallacy article that there is such an informal fallacy. One can make premature, inquiry quashing agent appeals to aliens, your older brother Jim, or God. At the same time, I’d want to add two additional points.

While there are fallacious explanatory appeals to God, it doesn’t follow that every explanatory appeal to God is fallacious

The first point can be made quickly: while there are fallacious explanatory appeals to God, it doesn’t follow that every explanatory appeal to God is fallacious. Unfortunately, those who grow accustomed to invoking the Goddidit charge quickly seem to lose sight of this very fact. And that’s the problem: you see, simply labeling every appeal to God with a derisive label like “Goddidit” is likely to quash proper evaluation of philosophically serious arguments. As a result, one fails to distinguish between asinine appeals to God and those that are worthy of serious consideration.

Consider again the fourth example from the list above:

The universe appears rather fine-tuned for life on earth. God did it!

Despite the inclusion of this example in the above-cited ignominious list, the fact is that serious philosophers of science like Robin Collins have provided rigorous, peer-reviewed arguments to justify appealing to God as an explanation of cosmic fine-tuning. And precisely none of those arguments can be reduced to “God did it” in a way that is relevantly analogous to the facile appeal to divine action to explain a chicken sandwich.

The Goddidit label often commits the Golden Hammer fallacy

This brings me to the second (deeply ironic) point. In order to set up this point, we should note first that according to the author of the Rational Wiki article, the Didit fallacy is a manifestation of the more general Golden Hammer fallacy which is defined as follows:

“a logical fallacy that occurs when you propose the same, simple solution (or type of solution) to every problem.”

Note the obvious hyperbole in the definition: precisely nobody proposes the same, simple solution to literally every problem. According to a less hyperbolic definition, the Golden Hammer fallacy occurs when the same solution is invoked for an implausibly broad range of issues, topics, or problems. A great example is the character Gus Portokalos in My Big Fat Greek Wedding. Whatever the problem, Gus has the answer: “Put some Windex.”

Note the obvious hyperbole in the definition: precisely nobody proposes the same, simple solution to literally every problem. According to a less hyperbolic definition, the Golden Hammer fallacy occurs when the same solution is invoked for an implausibly broad range of issues, topics, or problems. A great example is the character Gus Portokalos in My Big Fat Greek Wedding. Whatever the problem, Gus has the answer: “Put some Windex.”

Here’s where we come to the irony: while the person who appeals to God to explain something may commit the Golden Hammer fallacy, the same danger applies to the person who dismisses all explanatory appeals to God with the Goddidit rejoinder.

The post Goddidit and Golden Hammers appeared first on Randal Rauser.

September 13, 2016

How do you defend the Bible to those who dismiss it as the product of savage minds?

The other day I received an emailed question from a reader which focused on the problem of genocide in the Bible. The reader asked:

“If someone brought up these biblical narratives [of genocide], as Dawkins and the like have, as a means of discrediting the Christian faith and the biblical text how would you respond?”

Note how the reader put the question. He doesn’t describe a person who asks about these narratives because they are genuinely curious to know how Christians interpret the text. Rather, the person asks about the narratives as a means of discrediting the Christian faith. Needless to say, there’s a world of difference between these two approaches.

Imagine that you’re reading James Joyce on your lunch break when your coworker walks in the room and glances at the title. “Ulysses? Huh. I read a chapter of that in university, but I couldn’t understand it. How do you interpret it?” Now that’s a welcome invitation to a discussion. But imagine that instead he responds like this: “Ulysses? Hah! I was forced to read a chapter of that in university. How can you read that pretentious crap?”

If the first response is an invitation to dialogue, the second is little more than a polemical shot across the bow. Unfortunately, there are many folks who treat the Bible in this caustic manner, and Dawkins is but one of them. As a case in point, consider Richard Carrier who, in a recent review of my book Is the Atheist My Neighbor?, refers caustically to Christians who “are often aimed at ‘saving’ the Bible, from being the vomit of primitive and savage minds, by turning it into some sort of miraculously prescient treatise on 20th century science and logic that it’s not.”

Compare that with the skeptic who dismisses interpreters of James Joyce who are aimed at ‘saving’ Ulysses from being the vomit of a pretentious and obscure mind, by turning it into some sort of miraculously prescient treatise of 20th century culture that it’s not. Whether the text in question is Ulysses or the Bible, with that kind of starting point, the entire discussion is fated to realize an abortive conclusion.

So back to the question: if someone was concerned merely with discrediting the Christian faith, with unmasking that which they believe to be the vomit of primitive and savage minds, with guffawing at any interpretation that proposes to address their own moral incredulity, then I wouldn’t even bother having the conversation, for some conversations are not worth having.

How do you defend the Bible to those who dismiss it as the product of savage minds? The answer is this: you don’t.

But what about the person who is not yet prepared to dismiss the book as merely the product of savage minds? The person who is genuinely interested, who maintains an open mind, who seeks truly to understand and consider a perspective different from their own? That is, as they say, a very different kettle of fish, and I shall address it in a follow-up article.

The post How do you defend the Bible to those who dismiss it as the product of savage minds? appeared first on Randal Rauser.

Should Protestants accept the Deuterocanon?

In response to my article “Should additions to the biblical texts be treated as canon?” Simon K posed the following question:

“Did Protestants do the right thing by rejecting the deuterocanon? Should that decision be reconsidered? You are discussing here whether people should accept textual variants as inspired; but which books should be accepted in the canon seems at least a somewhat related question.”

(For those unfamiliar with the Deuterocanon, the Wikipedia article offers a decent overview of the topic.)

To be sure, while this is a different question than the one I posed, there is a shared principle: I was discussing whether we should grant canonical status to later interpolations in canonical books while Simon K was asking whether we should grant canonical status to a later canonical list (i.e. the Deuterocanonical list of seven books). Moreover, there is also a point of direct overlap insofar as the Deuterocanon includes additions to two Old Testament books, Esther and Daniel.

Certainly one could argue in the way Simon K has proposed. To illustrate, let’s return for a moment to the extended process of canon recognition in the early church. It would appear that by the early second century a nascent canon of four gospels and a collection of Paul’s letters had already formed. Thus, by the second century many Christians recognized the Nascent Canon.

Over the next two centuries various additional books — and thus various enriched canonical lists — would be proposed for acceptance (e.g. the Muratorian Canon of the late 2nd century). By the fourth century, it would appear the majority church had settled on the Protocanon that is accepted by the church today.

This brings us to the key point, the 27 book Protocanon is to the Nascent Canon as the Protocanon cum Deuterocanon is to the Protocanon alone. (Hopefully that makes sense!) In both cases we have Christian communities which had initially accepted a shorter canon then coming to accept a longer canon.

To sum up, this provides us with two reasons to consider the Deuterocanon. To begin with, just as I argued that a later form of a New Testament book (e.g. Matthew, Mark, or John) could be accepted as having the divine imprimatur, so a later canonical list could be accepted as having the divine imprimatur. Second, I pointed out that just as the early church embraced a later canon (the Protocanon) so likewise the later church could embrace a later canon (the Protocanon cum Deuterocanon).

To be sure, none of this means that Protestants should accept the Deuterocanon. It only means they should not exclude it in principle.

The post Should Protestants accept the Deuterocanon? appeared first on Randal Rauser.