Randal Rauser's Blog, page 144

August 30, 2016

Don’t try to redeem immoral practices by appealing to culture

A few years ago I wrote a Canadian member of Parliament to protest the annual slaughter of baby harp seals. I received a stock form letter in return thanking me for sharing my thoughts while informing me that the annual “harvest” of seals was a deeply entrenched part of the Newfoundland and Labrador culture.

From fox hunting to slavery, appeal to culture has long been a common defense of immoral practices. It’s also completely irrelevant. Whether or not a practice is a deeply entrenched part of one’s culture is of no consequence when assessing the morality of the action (unless, of course, you happen to be a cultural relativist).

We can put it this way: poutine (French fries with cheese curds and gravy) is very unhealthy. The fact that it also happens to be a staple cuisine of Quebec culture doesn’t change the fact that it is very unhealthy. And some practices are immoral. The fact that they also happen to be staple practices of a particular culture doesn’t change the fact that they are immoral.

And this brings me to the truly horrendous practice of Spanish bull-fighting. But not just bull-fighting. Yesterday I learned that it is common practice at many small town Spanish fairs to take a baby bull and stab it to death with skewers as a mock bull-fight. An animal rights group in Spain just posted video of one baby bull being stabbed to death over seventeen minutes as it cries, screams, vomits blood, and finally falls and dies while the villagers cheer and celebrate their “culture.”

In his book God, Humans, and Animals: An Invitation to Enlarge Our Moral Universe Robert Wennberg recalled how bear baiting used to be a common practice at the English county fair. C’mon Vicar! Let’s go watch a bear being tortured!

Incredibly, somehow English culture survived the elimination of this horrendous practice. And Spanish culture too will survive the elimination of the bullfight. Indeed, it will be the better for it.

http://www.stopbullfighting.org.uk/

August 29, 2016

The Question that Never Goes Away: A Review

Philip Yancey. The Question that Never Goes Away (Zondervan, 2014).

Philip Yancey. The Question that Never Goes Away (Zondervan, 2014).

Philip Yancey launched his illustrious publishing career close to forty years ago with the publication of Where is God When it Hurts? In his aptly titled 2014 book The Question that Never Goes Away Yancey returns to the enduring question of evil and suffering: why?

Three events in 2012 set the stage for this new book. To begin with, in March, Yancey was invited to speak in the Tohoku region of Japan on the one year anniversary of the devastating tsunami that claimed close to 20,000 lives. Then in October Yancey spoke in Sarajevo, a city in the former Yugoslavia that faced a four year siege in the early 1990s and was rent by ethnic hostilities and countless wartime atrocities. Finally, in December Yancey was invited to speak in Newtown, Pennsylvania just two weeks after the devastating Sandy Hook shooting. (By the way, the new Sandy Hook elementary school is opening, four years after the shooting.)

A raw depiction of evil

Yancey has always been an excellent writer and one who is not afraid of confronting the most difficult questions with disarming honesty and directness. Many Christian apologists understandably prefer to speak of evil in abstractions: i.e. “the problem of evil”. But Yancey does not flinch in describing the shocking horror of entire communities washed into the sea or a classroom of young children and teachers cut down by the gunfire of a deranged lunatic. And then there is this haunting summary of the evils that unfolded in the Balkans around Sarajevo: “Eyewitness reports from the court in The Hague read like a litany of horrors: pregnant women cut open, their unborn babies smashed with rifle butts; gang rapes of girls as young as nine; toddlers decapitated, their heads placed in their mothers’ laps.” (71)

One of the most agonizing moments in the book comes as Yancey recounts the moment the governor of Pennsylvania told panic-stricken parents their beloved children had died: “The governor’s senior advisor recalls, ‘It was a horrific scene. Some people collapsed on the floor. Some people screamed.’ Those outside the firehouse heard the wails and moans coming from inside. One witness likened it to a scene from the Middle East after a bombing when relatives beat their breasts and grief erupts.” (119-20)

Pastoral Comfort and Theodicy

A book that purports to wrestle with the question of why suffering and evil will presumably be shouldering the burdens of theodicy. But Yancey appears to be conflicted about this task, not least because he seems to consider theodicy (an intellectual exercise) as essentially linked to pastoral comfort (an emotional exercise). And theodicies are generally poor at providing comfort:

“After spending time in Japan and Newtown, I have adopted a two-part test I keep in mind before offering counsel to a suffering person. First, I ask myself how these words would sound to a mother who kissed her daughter goodbye as she put her on the school bus and then later that day was called to identify her bloody body. Would my words bring comfort or compound the pain? Then I ask myself what Jesus would say to that mother. Few theological explanations pass those tests.” (63)

It should not be a surprise to anybody that a mother facing the all-consuming agony of losing a child will not be comforted by any “theological explanation.” But that is quite irrelevant to the truth and importance of theological explanations. There is a time and place to explore theological and philosophical attempts to reconcile the divine nature with evil states of affairs. And measuring those efforts by their adequacy at providing comfort reflects a confusion of categories. They should be judged, rather, by their internal coherence and the evidence for them.

A Questionable Theodicy

Not surprisingly, Yancey does offer a theodicy of sorts in these pages. And while there are genuine pieces of wisdom and insight complemented by Yancey’s eloquent prose, it seems to me that his apparent decision to judge theodicies by the standards of pastoral theology rather than biblical, systematic, and philosophical theology lead him to make some questionable assertions.

For example, while Yancey concedes that God can redeem suffering, he appears very uncomfortable conceding that there is any providential intent behind the initial occurrence of evil. For example, he writes: “I resist those who assume that God sends the suffering to accomplish the good. No, in the Gospels I have yet to find Jesus saying to the afflicted, ‘The reason you suffer from hemorrhage (or paralysis or leprosy) is that God is working to build your character.” (96) Elsewhere he writes, “Never do I see Jesus lecturing people on the need to accept blindness or lameness as an expression God’s secret will; rather, he healed them.”(61) But again, it is simply fallacious to judge the quality of a theodicy by whether we (or Jesus) would share it with a person in the midst of suffering.

The problem is also evident in Yancey’s apparent discomfort with assertions of divine providence in the natural world. The 2011 tsunami in Japan provides Yancey with an excellent opportunity to explore natural evil. Not surprisingly, he joins the chorus of Christians who denounce any attempt to link natural disasters to the punitive divine will. He recalls how some Christians suggested the 2004 tsunami in the Indian Ocean was divine judgment: “Some televangelists credited it instead to God’s wrath against ‘pagan’ nations in that region that had been persecuting Christians. Along the same line one Christian leader traced the cause of the 2011 Japanese tsunami to the fact that ‘Japan is under control of the sun goddess.'”(59)

But what is particularly revealing is how Yancey denounces any linking of the punitive divine will to natural disasters. He states: “Theories ascribing disasters to God’s judgment end up sounding more like karma than providence.” (60) To be frank, that’s a very strange comment given that the Bible repeatedly attributes natural disasters to a punitive divine will. According to the biblical authors, God punitive causes plagues (Exodus 7:25-8:32), disease (Exodus 9:1-7), floods (Genesis 6-9), volcanic eruptions (Genesis 19:24), storms (Exodus 9:13-35), hail (Joshua 10:11), earthquakes (Isaiah 29:6), and drought (2 Chronicles 7:13-14). Whether you choose to call this “karma” or not, it is thoroughly biblical, and Yancey does his readers a disservice by ignoring this material.

Just as God is described as indiscriminately punishing entire populations through natural disasters, so the Bible also repeatedly describes him as punishing people through military assaults, arguably including the AD 70 Fall of Jerusalem (e.g. Matthew 24:45-51). But here too Yancey attempts to distance divine (punitive) providence from this event, choosing instead to say, “Once again God did not overrule, letting history take its course.” (88)

Insight, Wisdom … and Comfort

While there are problems in Yancey’s theology, as I said the book also brings genuine pieces of insight and wisdom. To note one, while Yancey is clearly uncomfortable affirming explicitly that God providentially permits evil and suffering for the moral formation of his creatures, he does tacitly endorse this theme at several points. For example, in 2007 when Yancey almost died in a car accident he found himself contemplating three questions: “Who do I love? What have I done with my life? Am I ready for whatever is next?” (50) And he recalls a friend fighting stage 4 cancer who embarked on a chemo treatment with this prayer: “she asked God to similarly use her ‘toxic, painful trial to destroy, starve and kill anything in my soul that is selfish, unholy, offensive to him.” (104)

Another theme in the book’s final pages is ecclesiological. In short, while the question where is God? is important and must be asked, it should be complemented by an additional question: Where is the Church? And thus, if people want to find God in this world of suffering, they can often look to the Christian workers in Japan, the Franciscan monks in Sarajevo, and Walnut Hill Church in Newtown (149).

Perhaps the most important theme in the book is hope. Yancey notes that far from shaking one’s faith, suffering often renews and deepens faith. He presents the example of Archbishop Desmond Tutu whose faith was forged through two years as head of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa (121-22). Through this experience Tutu did not discover the answers for why, but his faith and hope were deepened nonetheless.

Ultimately this hope is centered in the crucified and risen Son: “Because of Jesus, whom the New Testament describes as ‘the image of the invisible God,’ I can say with confidence that God is on the side of the sufferer.” (148)

Conclusion

In conclusion, from the perspective of theological and philosophical argument, The Question that Never Goes Away is a mixed bag as it muddles categories and makes some dubious assertions. But as with all Yancey’s books, it is eminently readable, it does convey some important theological points through vivid prose, and above all, it gives hope for those who suffer. Given that this is undoubtedly the book’s primary goal, one might call it a success.

If you enjoyed this review, please consider upvoting it at Amazon.com.

August 28, 2016

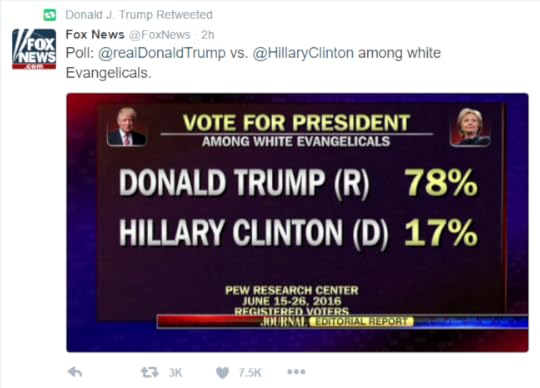

Evangelicals love Trump (or hate Hillary … or both)

August 27, 2016

On Donald Trump: Pity the psychopath, but don’t vote for him

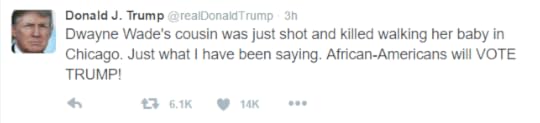

In another tragic instance of ongoing internecine urban violence, the cousin of basketball star Dwyane Wade was just tragically shot and killed while pushing a baby stroller. Donald Trump wasted no time in exploiting this horrific tragedy to serve his own interests (while misspelling Wade’s name in the process):

Now it is no secret that politicians regularly exploit tragedies for political gain. What is truly striking about this beastly tweet is the complete lack of emotional intelligence, the sheer crassness, the shocking ignorance of human compassion, that it demonstrates. And of course with Donald Trump this is a well-established pattern. In the wake of the Orlando tragedy he posted a tweet much like this.

The fact is, however, that this tweet demonstrates in chilling fashion the barren internal landscape of the clinical psychopath. This is the person who is blind to the affective and volitional dimensions of moral tragedy much like the color-blind person is blind to the difference between green and blue.

In other words, it isn’t that Trump is callous to human suffering, for callousness assumes some ability on the part of the individual to sympathize with and show compassion for others. Trump completely lacks that ability: in his small world it’s all Trump all the time. And the misery of others is nothing more than another shovel full of coal into the self-aggrandizing Trump train.

This leaves me in the curious place of pity. I pity Trump and his small world bereft of care and compassion for others. And with that in mind, I’d encourage you to frame your own condemnation of the man with a dose of pity.

Pity Trump, but for goodness sake, don’t vote for him.

August 26, 2016

On those who call for an end to philosophy of religion

As my regular readers will know, I have a book co-authored with Justin Schieber forthcoming in which we debate the existence of God. Debates on the existence of God belong to the field of philosophy known as the philosophy of religion. Thus, Justin and I are engaged in an extended debate within the philosophy of religion. I, the theist, argue for God’s existence while Justin, the atheist, argues against God’s existence.

In the last couple years I’ve noticed that John Loftus has begun advocating for what I’ll call the exclusion thesis according to which the philosophy of religion should be excluded from the Academy. Indeed, he apparently has written a book calling for the end of the philosophy of religion: the subtitle is “Why philosophy of religion must end.” According to the promotional blurb,

“Just as intelligent design is not a legitimate branch of biology in public educational institutions, nor should the philosophy of religion be a legitimate branch of philosophy. So argues leading atheist thinker and writer John Loftus in this forceful takedown of the very discipline in which he was trained.”

Absurdity

Now this is surely one of the weirder positions ever to emerge from the atheist blogosphere. Note that the claim is not merely that theism is not an intellectually credible position within philosophy of religion. If that subtitle and the promotional material is to be believed, the real claim is that philosophy of religion itself is intellectually delegitimated. In other words, the person who defends atheism (e.g. Justin Schieber) is as illegitimate as the person who defends theism.

Frankly, I’m surprised that Loftus found a publisher for so bizarre a thesis as this. According to this thesis, atheist J.L. Schellenberg’s defense of the hiddenness thesis is as illegitimate as theist Michael Rea’s critique of it. And atheist Quentin Smith’s critique of the cosmological argument is as illegitimate as William Lane Craig’s defense of it.

This thesis has a very curious implication. You see, philosophy of religion is concerned with presenting arguments and evidence for and/or against religious/irreligious and theistic/atheistic claims. Thus, the person who rejects the entire discourse rejects the propriety of providing arguments or evidence for or against religious/irreligious and theistic/atheistic claims.

In other words, the atheist who rejects the discourse of philosophy of religion rejects the provision of arguments and evidence in favor of atheism.

From which it follows that the atheist who rejects the discourse of philosophy of religion advocates for a de facto fideism for their atheistic commitments.

As if that were not bad enough, even worse, fideistic atheism is itself an argument in the philosophy of religion. Thus, the proponent of the exclusion thesis contradicts the very thesis he purports to endorse. By arguing de facto for fideistic atheism, he contradicts his own prohibition against the philosophy of religion.

Equivocation?

Perhaps Loftus is not really rejecting the legitimacy of philosophy of religion per se. An alternative reading of his project is suggested as one keeps reading the promotional blurb which continues like this:

“In his call for ending the philosophy of religion, he argues that as it is presently being practiced, the main reason the discipline exists is to serve the faith claims of Christianity. Most of philosophy of religion has become little more than an effort to defend and rationalize preexisting Christian beliefs.”

The latter part of the promotional blurb seems to shift from a rejection of philosophy of religion per se to a rejection of Christians doing philosophy of religion. Apparently J.L. Schellenberg and Quentin Smith are permitted to defend their preexisting atheistic beliefs, but Michael Rea and William Lane Craig are not permitted to defend their preexisting Christian beliefs.

If that is the case then Loftus is merely guilty of a particularly bald form of equivocation. He advertises a surprisingly robust rejection of the entire discipline of philosophy of religion but then shifts his target to Christian philosophy of religion.

Rest assured, whether the matter is absurdity or equivocation, philosophy of religion is alive and well.

August 25, 2016

New endorsements for An Atheist and a Christian Walk into a Bar

“Imagine sitting at a table in your local bar or coffee shop and overhearing two smart, energetic, and creative thinkers go at it over the existence of the Jewish/Christian/Islamic god. Thanks to Rauser and Schieber, we don’t have to imagine: this book is that debate. Anyone who enjoys a hard-hitting but classy philosophical dustup will love this fun and informative book.”

—Guy P. Harrison, author of 50 Simple Questions for Every Christian and 50 Reasons People Give for Believing in a God

“Fun, thoughtful, and surprising. Rauser and Schieber engage in passionate, thoughtful, and—this is key—civil conversation on the enduring question of whether or not God exists and why that matters. Grab a cup of coffee or a favorite pint and buckle up. You’ll find yourself reexamining what you thought you believed—or didn’t believe—about God.”

—Bryan Berghoef, author of Pub Theology: Beer, Conversation, and God

“Schieber and Rauser offer something sadly too rare: a civil, respectful, and reasonable dialogue over the question of the existence of god. At a time when theists and atheists usually just lob rhetorical bombs at each other over a figurative DMZ, that’s a rather refreshing thing, regardless of which side you come down on.”

—Ed Brayton, writer at Dispatches from the Culture Wars and 2009 recipient of the Friend of Darwin Award from the National Center for Science Education

“A refreshing book with perfect sparring partners! Schieber and Rauser insightfully refute bad arguments related to atheism and also highlight issues that need more attention within the popular debate over God’s existence.”

—Trent Horn, author of Answering Atheism

“A book that balances accessibility, rigor, and probing creativity, it has the potential to bring into the mainstream the sophistication and constructive insight of academic philosophy of religion—something often sorely missing from the preachers and polemicists who hog most of the attention in the theism/atheism debate.”

—Daniel Fincke, founder and primary writer of philosophy blog Camels with Hammers

August 24, 2016

Unveiling the New Tentative Apologist Logo (and its retro roots)

If you haven’t yet watched Stranger Things on Netflix, this may not resonate with you. It’s a fantastic retro-80s show with supernatural mystery cloak-and-dagger themes that provides ample homage to Stephen King, Stephen Spielberg (especially E.T.), John Carpenter, The Goonies, and all things eighties (Think of the retro 2011 film Super 8).

For a great illustration, consider how the soundtrack and opening sequence of Stranger Things draws inspiration from the past. With apologies to John Williams my sentimental favorite soundtrack of all time comes from John Carpenter’s 1981 film Escape from New York. Here’s the opening credits and sequence (it’s hilarious that “1988” and “1997” seemed like the distant future when I first saw this movie):

Now consider how Stranger Things channels John Carpenter in its own opening. It’s hard to believe this is brand new when it sounds and looks like it came out during Reagan’s first administration:

All that is intro for the unveiling of my new Twitter logo:

And here’s the good news for you. If you want to make your own Stranger Things logo, you can do so at http://makeitstranger.com/

August 21, 2016

Belief in God as Properly Basic? The Debate Continues

I just finished listening to this week’s episode of “Unbelievable”, titled “Is belief in God ‘properly basic’? Tyler McNabb vs Stephen Law.” Incredibly, Justin mentioned that this is the first time they’ve devoted a show to the epistemological question of whether belief in God can be properly basic. Given that it is a topic which has received an enormous amount of attention in the last twenty years, that was definitely a surprise.

The two participants were Tyler McNabb, a Christian PhD candidate in philosophy and Stephen Law, an atheist philosopher and academic whose output is of sufficient cultural significance that he has attained that lofty title of public intellectual (at least in my estimation).

In this article I’m going to offer some quick reflections on the McNabb-Law exchange, but you will be far better served if you first take the time to click on the first link above and devote an hour to listening to the show before you read the rest. Don’t worry, I’ll wait. It shan’t take long.

*waiting*

Okay, now that we’re all on the same page, I’m going to offer some comments on the show.

For starters, I thought McNabb did a decent job of explaining his position, though he did try to pack too much technicality into a popular radio format. But Stephen Law and Justin Brierley compensated by simplifying and restating where needed. Regardless, I commend McNabb for a concise presentation. He was clear and confident and amiable. I also am in fundamental agreement with his position. (However, I tend to make the same point by focusing on testimony within the Christian community rather than via a mysterious sensus divinitatis because I believe the latter places the theist at a rhetorical disadvantage. But that’s a relative quibble.)

My two main points are in response to Law. Of these, my first point is to underscore how much Law conceded to McNabb. In short, Law agreed with McNabb that an externalist epistemology in the reliabilist school is likely correct. (I don’t know if McNabb would agree that proper functionalism should be considered as a token example of reliabilism, but I suspect we can all agree that the two are at least kissing cousins.) Moreover, Law agrees that belief in God cannot be excluded a priori from inclusion in the sphere of beliefs which are held as properly basic.

This means that the essence of the debate between McNabb and Law is whether there are defeaters sufficient to undercut the prima facie justification for theists who are aware of all the live defeaters. Law’s concession on this point is huge. You see, if you spend any time interacting with average atheists on the ground you encounter the attitude that Alvin Plantinga and proper basicality are a joke, a bald ad hoc attempt to shore up theistic belief in a last ditch attempt to avoid the overwhelming evidence against it by finding a non-evidential means to justify theism. However, Law agrees that some form of externalist epistemology is probably correct. And that, in turn, shifts the discussion from externalist epistemology per se to the question of whether there are defeaters sufficient to undercut the prima facie justification of an informed theist like McNabb. (Note that Law’s position already cedes the rationality of uninformed theists who accept God’s existence and are simply unaware of any defeaters.)

My atheist friends need to grapple with this fact. So let me repeat it for good measure. Law does not dispute the nuts and bolts of Plantinga’s externalism. He only disputes whether the defeaters for theism are sufficient to undercut the justification for a theist who is aware of those defeaters, i.e. a person like McNabb.

So how strong is Law’s case? Does he present a defeater of sufficient force to undercut the justification of folks like McNabb? To make his case, Law points to the fact that we are unreliable agency detectors. That is, we are liable to find agency where none exists. From this, Law claims that we ought to draw the general skeptical conclusion that we cannot trust our basic beliefs about invisible agents (like God).

It is at this point that I depart from McNabb and offer a different response to Law. My response goes like this: Fair enough, humans are fallible when it comes to forming beliefs about (invisible) agency. I concede that point. But here’s the thing. Humans are also fallible when it comes to forming beliefs about the past. If you don’t believe me, read the article “Why Science Tells Us Not to Rely on Eyewitness Accounts.” There you will read a sobering discussion of how human memory works. The author observes:

“Many people believe that human memory works like a video recorder: the mind records events and then, on cue, plays back an exact replica of them. On the contrary, psychologists have found that memories are reconstructed rather than played back each time we recall them.”

While memory is obviously fallible — indeed, highly fallible — few of us are willing to concede that these observations are sufficient to warrant a blanket skepticism about all the deliverances of our memory.

With that in mind, we now come to Stephen Law. Law argues that our beliefs about agency acting in the world are unreliable. As with the memory case, I’m willing to concede the general point. But just as I require more evidence to concede that I can never trust my memory, so I will require more evidence if Law wants to claim that I can never trust my beliefs about invisible agency.

The Sobering Case of a Serial Plagiarist

During my time in England working on a PhD (1999-2001) I developed several acquaintances within the academy including the philosopher Martin Stone. The last I’d heard, Stone had left England for a professorship in Belgium, but I hadn’t heard anything of him in years. So a few days ago I plugged “Martin Stone” and “philosophy” into a google search engine to see where he was at.

The results were shocking.

The stage is nicely set by Sally Sharif in her article “Where Does Disdain for Plagiarizers Stream From?” Sharif asks, “Who was Martin Stone?” And then comes the shocking reply:

“He is the Voldemort of the Institute of Philosophy: his name is not to be said. One utters it and a hush falls upon the audience. He was Distinguished Professor of Renaissance and Early Modern Philosophy before being forced to resign. What he did has often been described as an act that shook the world of scholarship. In 2010, KU Leuven retracted its affiliation with Stone’s publications, after it was discovered that …”

Good gosh man, what was discovered? What’d he do? Murder? Kidnapping?

Sharif continues:

“… almost all of them [Stone’s publications, that is] had been partially or wholly copied from works of other authors. This includes the Ph.D. thesis of a member of the Finnish Parliament.”

Whoa. Wait, are you serious? Indeed, it turns out that the brilliant young(ish) scholar was, in fact, a serial plagiarist. Three academics that led the charge in chronicling Stone’s crimes compiled some of the evidence in a meticulously researched paper titled “40 Cases of Plagiarism.”

And yeah, that includes the above-mentioned member of the Finish Parliament, Ilkka Kantola, from whose 1994 thesis Stone plagiarized “tens of pages … identical or nearly identical….” (See “Plagiarism probe sees UK scholar quit Belgian post“.)

I’m struck by the brazenness of the crime. I’ve never knowingly plagiarized anyone, and if I had I’d likely be wracked with anguish at being found out. This kind of flagrant deception cries out for psychoanalysis.

Anyway, I’m not sure what to do with this information except to reproduce my shock here and issue a warning as a new academic year begins. Whether it comes through carelessness or deception the crime is the same: the presentation of the thoughts, words, or ideas of someone else as your own is theft. And whatever you may think, it ain’t worth it.

August 19, 2016

Richard Carrier reviews Is the Atheist My Neighbor?

Richard Carrier just posted a review of my 2015 book Is the Atheist My Neighbor? Rethinking Christian Attitudes Toward Atheism. Titled “Randal Rauser on Treating Atheists Like People,” Carrier’s review has lots of nice things to say: he calls the book “brief but thorough and well-studied” and he observes, “it makes a better argument in defense of atheists than you might ever muster yourself. Not in defense of atheism being correct. But in defense of atheists themselves, as people deserving of respect and dignity, and of being taken seriously, as intelligent, reasonable, ethical people.”

But this isn’t a puff piece. In keeping with his signature style, Carrier carefully analyzes the argument and offers thought-provoking criticism complemented with incisive rhetoric. He then closes with the hope that some day I might become an atheist and antitheist. Um, no thanks, but I appreciate the kind wishes.