Aaron Elson's Blog, page 21

September 24, 2012

Darrell Petty Part 2: The Death Camp Doctor

Klaus Schilling At the 1997 reunion of the 90th Infantry Division, I met Darrell Petty of New Castle, Wyoming. My tape recorder missed the beginning of our conversation, but at the start we were talking about the crossing of the Moselle River in November of 1944. The river was at flood stage, and the infantry crossed before the heavy equipment, including the tanks of the 712th Tank Battalion, could cross on a bridge. The fighting was intense, and the infantry was at risk of being pushed back into the river when the tanks finally did get across and helped to turn the tide of the battle.From there the conversation turned to the division's second crossing of the Moselle River, in March of 1945. Initially I made two separate stories in Darrell's words out of this interview, but here I'll post the interview itself, with a brief postscript. (See Darrell Petty Part 1: Machine Gun Hill)

Klaus Schilling At the 1997 reunion of the 90th Infantry Division, I met Darrell Petty of New Castle, Wyoming. My tape recorder missed the beginning of our conversation, but at the start we were talking about the crossing of the Moselle River in November of 1944. The river was at flood stage, and the infantry crossed before the heavy equipment, including the tanks of the 712th Tank Battalion, could cross on a bridge. The fighting was intense, and the infantry was at risk of being pushed back into the river when the tanks finally did get across and helped to turn the tide of the battle.From there the conversation turned to the division's second crossing of the Moselle River, in March of 1945. Initially I made two separate stories in Darrell's words out of this interview, but here I'll post the interview itself, with a brief postscript. (See Darrell Petty Part 1: Machine Gun Hill)Darrell PettyOmaha, Neb., Sept. 1997 Aaron Elson: Were you wounded?

Darrell Petty: I was wounded twice, actually three times. Once I didn’t even, the line medic patched me up and that was it.

Aaron Elson: Where were you wounded?

Darrell Petty: Just outside of Chambois, when we closed the Falaise Gap, the first time. The second time I got it was in the Siegfried Line. And the third time that I got a minor wound was about two weeks before the end of the war.

Aaron Elson: And where was that?

Darrell Petty: Getting pretty close up to Czechoslovakia. I don’t remember just where, what town.

Aaron Elson: Before the liberation of the concentration camp?

Darrell Petty: After we went to Flossenburg.

Aaron Elson: Were you with them at Flossenburg?

Darrell Petty: Yeah. Flossenburg was the last one that we took. You won’t find it in the books or nothing, but the 4th Armored and part of our unit went to Buchenwald, too. But you won’t find it in any history book, because we were stopped at Merkers, where the gold reserves were. And Patton said it doesn't take us all to watch Merkers, and there was a little place called Ohrdruf or something like that. It was supposed to be a work camp. But we got there and there were bodies stacked up. A lot of them had come from Buchenwald. They were stacked up. First encounter. And we went to Buchenwald. The Germans were gone, the prisoners had apparently taken Buchenwald over by that time, but we saw what was there. And of course, that old camp commandant’s wife, she was called the Bitch of Buchenwald, because she liked tattoos, she made lampshades.

Aaron Elson: Ilse Koch?

Darrell Petty: Yeah, I guess. I don’t know, I don’t remember her name, I just called her what they called her. But anyway, the one unit...

Aaron Elson: Were you with that unit?

Darrell Petty: Yeah. And we went to Buchenwald, but you don’t find it.

Aaron Elson: Had Buchenwald already been liberated?

Darrell Petty: No. But the Germans knew we were going to overrun it and most of them had fled, and they took quite a lot of the prisoners from Buchenwald to Flossenburg. Then they tried to take them from Flossenburg to Dachau. So, like I said, most of the Germans were gone and the prisoners were actually about in charge of Buchenwald when we got there. But it was still in enemy territory at the time.

Aaron Elson: So you actually went to Buchenwald before it was liberated?

Darrell Petty: As it was liberated. The 4th Armored and a unit from our outfit and another outfit.

Aaron Elson: Did you go into it?

Darrell Petty: Oh yeah, we went in there.

Aaron Elson: And what did you see?

Darrell Petty: Bodies. Everything you can imagine. It horrified us, and we’d seen those bodies at that other one, I couldn’t say its name, and most of them had come from Buchenwald, so we were kind of prepared for it, but still it was...

Aaron Elson: Were any of the German guards captured at the time?

Darrell Petty: The prisoners had got some of them. The prisoners had killed some of them, they caught them, they killed quite a few, the ones that hadn’t got out of there. Once they got control, they went hunting. A revenge thing, and I couldn’t blame them. But where they were shipped to, down there at this other place, they had heavy equipment there and they were supposed to have dug trenches and got them buried before we got there, and they didn’t get it done.

Aaron Elson: And it was just the emaciated bodies?

Darrell Petty: Yeah, I’ve got a few pictures at home. So many times you’d take pictures. I got ahold of a camera, and you always got a moment to stop and snap a picture. We’d have to cross a river or something, you’d get the film wet, it was the old roll type, 120s and that. I’d have had more than I got. I’ve got some from Flossenburg, and Dachau.

Aaron Elson: Did you take any at Buchenwald?

Darrell Petty: I took some, but I lost them, before I got it. And then, after the war was over, I was still enlisted for a while. I enlisted, and instead of coming home with the division, I stayed over there in the army of occupation and they transferred me back to Munich, and I was attached to the 508th MP battalion in Munich. And when we weren’t doing the other stuff we just pulled regular MP duty. But we were at Dachau, at the war crime trials, and at Nuremberg, we were part of them.

Aaron Elson: Were you at Dachau for the war crimes trials? You never ran into a fellow named Clifford Merrill, did you? He retired as a colonel, but he had been a captain, but he was in charge of MPs at the Dachau...

Darrell Petty: I probably saw him, but you know, so many times, like I said, we didn’t know names. Didn’t bother with names. And if you didn’t know the guy, why, he was just another GI. I most likely saw him, I probably saw him there.

Aaron Elson: He was an officer of the MPs. He had contact with that Ilse Koch, and also there was one famous prisoner there, Otto Skorzeny, he was the commando who tried to capture Eisenhower, and who had freed Mussolini the first time, he was one of the prisoners there.

Darrell Petty: I don’t remember the name, but, you know, one that stands out in my mind was old Dr. Schilling.

Aaron Elson: Why does that stand out?

Darrell Petty: Because he did so much experimenting on the people and that, you know, he was the camp doctor...

Aaron Elson: At which camp?

Darrell Petty: Dachau. And he experimented on those people. Even when we took those places it was horrible to see what was there, but we still didn’t know about all the experimentation until the trials. And, uh, I come within an inch of shooting him.

Aaron Elson: Really?

Darrell Petty: That’s one of the reasons he stands out, I guess. Because we’d just been on his case, and I wasn’t at all the trials of Dachau, because they switched us back and forth. But we had some guys that had never seen an ounce of combat, who came over there later. And we had one new guy in there, and I won’t mention no names, I don’t want to implicate anybody, but anyway, he’d never seen combat. And he had a little .30 carbine, that was just semiautomatics at that time, and 15-round clips. But there would be a clip in the gun, and two clips on the butt of it. That’s 45 rounds. Okay. He’s standing there gawking around and he wouldn’t be protecting that gun. I got on him several times. I told him, "You protect that firearm." I said, "These guys don’t have anything to lose." Well, these guys that lived such a high muckety-muck life, it was kind of satisfying to see them sniping cigarettes off the floor, and they were eating some pretty thin soup that we brought for lunch, and they were in a soup line. That day it was some pretty thin soup. And this kid was standing there gawking around and he’s got the butt of the rifle grounded on the floor, and gawking around and not looking at them at all, he was looking around. And I just about went over and said something to him and I didn’t. And by golly, old Schilling was in line, and I, I just loathed him for what he’d done to people. And all at once he made a dive toward this kid, and the first thing flashed in my mind was he’s going for that carbine. I had a .45, and I always had it full loaded, the hammer on half-cock and the safety on. And he dove like he was reaching for that rifle. Well, as it turned out there was a cigarette butt about that long, boy, that was a prize, between that kid’s foot and the butt of the rifle. That’s what he was going for. But I didn’t know that. And I grabbed the old ‘45 and I dropped the safety, and cracked the hammer full, and when he came up with that cigarette, I was about from here to there ...

Aaron Elson: About six inches?

Darrell Petty: That half-hole looks awful big.

Aaron Elson: From his face?

Darrell Petty: And he just drained, his color just drained. "Oh, nein! Nein! Bitte! Bitte! Zigaretten, Rauchen! Rauchen! Bitte, nicht schiessen!" Don’t shoot, you know. Please. Rauchen is smoke. I never had a feeling like that in my life, before or since. But I wanted to pull the trigger. And I couldn’t hardly keep from pulling the trigger. And I finally just pushed my finger off of it. And I dropped the safety on, and I grabbed him and boy I throwed him back in the line and I told him to stay there, and he’d complained to me before about having to go to the bathroom a lot of the time, he’d had surgery, I suppose, prostate, I don’t know. But anyway, I thought, "Yeah, you, I sure feel sorry for you, you ..." And when I got done, I was mad. I throwed him in that line, and I done a pirouette and I kicked that kid just as hard as I could kick him right in the hind ...

Aaron Elson: The kid, the other MP?

Darrell Petty: Yes. And he lost his grip on the rifle and I grabbed that before it hit the floor, and he went down. And I stood above him, I had that butt of that rifle right in his face. And man, I told him in no uncertain terms what I’d do to him if I ever saw him, and I said, "Much as I wanted to do it, you almost made me kill a man without a reason." And I was just hyper, I was just, you know...

Aaron Elson: About how old were you at the time?

Darrell Petty: Nineteen. I went in at 17. And I was overseas at 17.

Aaron Elson: How’d that happen?

Darrell Petty: Well, my folks signed for me to go in, and when my unit shipped overseas, they didn’t say I couldn’t go, and I didn’t tell them I wasn’t supposed to go, and I went. I left New York in January of 1944 and was in England seven days later, well in Scotland seven days later. And then I went down by Cardiff, and the 90th hadn’t got there yet. I was assigned to the 90th about the middle of April. But I’ll tell you what, from that time on that kid was like this, he was looking at everything, with that carbine. I never saw him even look like he was gonna put it down after that. I could have got courtmartialed, I suppose, but at the time it did not matter. I was mad. I said, "You didn’t only pretty near make me kill him," I said. "He had nothing to lose. He could have grabbed that little carbine and started spraying us." It’s a pretty deadly little weapon at close range, I’ll tell you.

Aaron Elson: How old was this Dr. Schilling?

Darrell Petty: Probably middle age. At the time he looked quite old to me, but you know, they do when you’re young like that.

Aaron Elson: Was he executed, or what happened to him?

Darrell Petty: I don’t know whether they executed him or not...

(Coming soon: Darrell Petty, Part 3)

Got Kindle? My book "Tanks for the Memories" is available for a free download today (Sept. 25) only, a savings of $3.99 over the Kindle price and $13.95 over the print price. And I sure could use a couple of reviews at amazon, where a disgruntled reader just gave it a measly one-star review, and another gave it two stars. Phooey. If you enjoy reading these blog entries, which are similar to the source material in my books, I hope you'll make your enthusiasm known via a review at amazon. Thank you, Aaron

Postscript: According to testimony at the Dachau War Crimes trials, Dr. Klaus Schilling conducted malaria experiments on 1,200 inmates at Dachau. He was convicted and sentenced to death by hanging. The sentence was carried out in 1946.

- - - From Oral History Audiobooks: Encounters With General Patton

The Tanker Tapes From D-Day to the Bulge The D-Day Tapes From Chi Chi Press: Tanks for the Memories A Mile in Their Shoes Got Kindle? Conversations With Veterans of D-Day Nine Lives: An Oral History They Were All Young Kids

Published on September 24, 2012 20:56

September 22, 2012

Darrell Petty Part 1: Machine Gun Hill

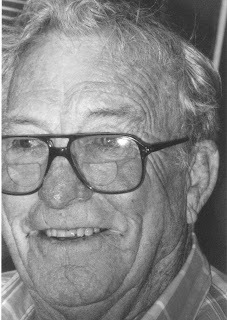

Darrell Petty I met Darrell Petty, of New Castle, Wyoming, at the 1997 reunion of the 90th Infantry Division in Omaha, Nebraska. My tape recorder must have missed the beginning of our conversation, but at the start we were talking about the division's crossing of the Moselle River in November of 1944. The river was at flood stage, and the infantry got across two or three days before the first tanks were able to cross on a bridge. The fighting was intense, and the infantry was at risk of being pushed back into the river when the tanks finally did get across. From there the conversation turned to the division's second crossing of the Moselle, in March of 1945, under greatly different circumstances. Darrell Petty, G Company, 358th Regiment, 90th Infantry Division

Darrell Petty I met Darrell Petty, of New Castle, Wyoming, at the 1997 reunion of the 90th Infantry Division in Omaha, Nebraska. My tape recorder must have missed the beginning of our conversation, but at the start we were talking about the division's crossing of the Moselle River in November of 1944. The river was at flood stage, and the infantry got across two or three days before the first tanks were able to cross on a bridge. The fighting was intense, and the infantry was at risk of being pushed back into the river when the tanks finally did get across. From there the conversation turned to the division's second crossing of the Moselle, in March of 1945, under greatly different circumstances. Darrell Petty, G Company, 358th Regiment, 90th Infantry DivisionOmaha, Neb., Sept. 1997 Darrell Petty: ...Anyway, it didn’t sound like a German tank. But imagine that sucker coming around that corner into view, the first thing I saw was the end of the barrel on that muzzle break, I thought, oh, man, they got tanks behind us. Boy, I was sure glad to see that old white star shining on that sucker, I’ll tell you. It made a whole bit of difference, I’ll tell you.

Aaron Elson: They got one platoon of tanks across the Moselle, just in time from what I understand.

Darrell Petty: Well, I’ll tell you. It was a lot different the second time I crossed it. I crossed on a bridge. But then we ran into quite a firefight on Hill 451.

Aaron Elson: Where was that?

Darrell Petty: We were supposed to be in reserve. F Company had pulled up on the line and we were in reserve, and we left, I can’t think of the name of that town, just right on the banks of the Moselle on the other side. We billeted in houses. We took over houses, we felt pretty secure by that time in the war. So we started marching up in reserve, and we could hear digging. We knew somebody was digging in, but we didn’t know who. And we went up a hill, a pretty damn steep hill, and a guy by the name of Gene Miller and I, we helped another guy up. His name was Prey. He was a private first class, and if I knew then what I know now he was having a heart attack. But we didn’t know it. He carried a little 536 radio. I was packing that, and they’re pretty heavy those little devils. And Miller was packing his M-1 rifle. We were lightening the load up for him as much as we could. And just the day before that we’d chopped his hair off, it had gotten long, it looked like the devil.

But anyhow, we got to the top of the hill, then we sat down for a break. We could still hear these guys digging in, whoever it was, and it turned out it was F Company. And we were just setting there, and about that time here comes a machine gun burst.

The Germans shoot white tracers, ours were orange, so we knew that it was definitely German. By the sound and by the tracers, they shot just about twice as fast as our Brownings did. And man, we whirled around and headed for cover. And this kid, this Pfc. Prey, he let out a groan and collapsed. We figured he was hit. We got over the hill and then hollered "Medic!" And a guy by the name of Doc Roberts, Thomas Roberts, a field medic but everybody called him Doc, he came up, and he and I crawled out there to Prey. We got ahold of him and dragged him back behind cover. And he was gone. And he had a classic look of a person with a heart attack, in his face, the coloration of his face. We tried to find where he was hit. We couldn’t find any blood. He didn’t have a bullet mark on him. He died of a heart attack. And we lost him. He was the only dead one. We had some wounded. And Lieutenant Colonel Cleveland A. Lyttle was leading us, he was the battalion commander, and he went right up that hill with us.

All we know is they said there were machine guns on the hill, well, that was standard. If we’d have known what was on it we probably wouldn’t have tried it. They pinned F Company down and they had killed 25 men in F Company and wounded some others. There were five companies of German SS, they were dug in, and they had 40 ground type machine guns on that hill. And F Company had just buggered into them. They weren’t supposed to be there, by all the reports there was nothing there. And Lyttle came up and he said, "We’ve got this hill to take, it’s got some machine guns on it, we’re gonna take it."

Okay. F Company’s pinned down. So, we called in artillery, everything they had, and boy, they were tossing them in there close to us. So we had to go down the hill, under trees. And we had to cross the valley, that’s where they pinned F Company down.

We went through F Company, and we headed up that hill. But when we got underneath that canopy where we could look up under there, man, it looked like an anthill. There were Germans running all over that hill. Well, hey, you couldn’t do anything but go forward. If we turned around and retreated, we’d have been just like F Company. So we just kept going, and they’d taught us use that march and fire, every time your right foot hit the ground, if you had a carbine you fired it, and we got good shooting from the hip. Heck, I could throw a small bucket out and fire when I throw it and hit it five, six times out of eight out of that M-1 Garrand. And that’s the way we went up that hill. And that colonel, he went up the hill with us. Our watches were all synchronized when the artillery was gonna stop, so we knew what time to hit the hill. And when we got to the top, we only took one German prisoner.

Aaron Elson: Just one?

Darrell Petty: One. He was a sergeant, spoke English, and he said, "You damned Americans are crazy. You don’t know how to fight a war." He said, "When you’re fired on with full automatic weapons you’re supposed to hit the ground and take cover. That other unit did and you guys didn’t. You just kept coming at us. We couldn’t get our heads up to shoot back straight." And it made "Army Hour," and was broadcast all over the free world.

Aaron Elson: You know, that’s what they told me. I’ve met some of the Germans who fought there, in one of the villages, and one who spoke English said the Americans didn’t know how to fight.

Darrell Petty: Oh yeah. He said we took war for sport, because we laughed at things. Sometimes it was either laugh or cry, so we laughed. And by golly, it’s an awful thing to say, but we shouldn’t take prisoners, because if you stand there guarding that prisoner you’re gonna get shot. And some, most of them tried to fight, but a few tried to surrender. You couldn’t stand there and guard him because you’re going to get shot. Plus we needed everybody up the hill. So you just had to do what you did.

Aaron Elson: The Germans on top of the hill, were they killed by the infantry or by the artillery?

Darrell Petty: Infantry. We took a kid by the name of Speaks, he had a B.A.R., and I had an M-1, and old Thomas [Doc Roberts] was like a squad leader. He was right up there on the front end of that thing with us, that medic, and by golly, we overran the CP, the command post up there, and a full German colonel came out of there and his cadre, and they were running and we opened up on them with a B.A.R. and that M-1 and it just folded them up. There was one still alive, and Roberts went down and was gonna try to help him, and I heard a Schmeisser bolt click and I hollered "Doc! Look out!" I looked up the hill and he was taking aim on old Doc, and Doc just fell down among the bodies and he sprayed him and he finished killing the German, but he didn’t get Doc. And about that time Speaks and I opened up on him, with the B.A.R. and the M-1.

He was gonna kill Doc, and Doc was trying to help a German, wounded. He killed the German, and Doc fell in behind the bodies and he didn’t get him. Then we nailed that guy. And my M-1 was so hot it wouldn’t quit firing, it was setting itself off. And on the way up, a kid by the name of Phyllis, in F Company...

Aaron Elson: Phillips?

Darrell Petty: Phyllis, just like a girl’s name, his last name was Phyllis. He was mad, and he jumped up, and he said, "I’m going with you!" He went through basic with us, this other kid and me.

Aaron Elson: He was from F Company?

Darrell Petty: Yes. And he shouldn’t have even went with us, but he did. And halfway up the hill I got a bunch of machine gun bullets through the pant leg, and they cut him down. And I thought my leg was gone, it felt like somebody knocked it off. I looked down, it was still working, it was okay. But if he hadn’t went with us, a kid out of Prescott, Arizona, by the name of Billy Bacon and I, we would have run out of ammunition halfway up the hill. We went back and got his ammunition and finished it up, and when it was done I had 18 rounds left. We split it, and I had 18 rounds left, and we were expecting a counterattack. We were setting there with dang little ammunition, but as it turned out, this German sergeant, he'd seen what was going on and he played dead, he smeared blood on his face and lay there. When we discovered he was alive, Lieutenant Kelso said "I want to talk to him," because old Sergeant Will was about to kill him. Lieutenant Kelso said, "I want to find out what they’re doing here." As it turned out, they were supposed to let us bypass them, and then they were going to hit us from the rear that night, and the 11th Panzer was going to hit us from the front. And when we found out, we called artillery in on where the 11th Panzer was gonna come in and we foiled the whole thing.

We were put in for a presidential unit citation for that. And it was on Army Hour, broadcast all over the free world. And I have the little article, I’ve got it at home, where it says Colonel Lyttle and G Company of 358 outmaneuvered and destroyed five companies of German SS, and I’ve had people look at me about those holes. I had seven holes in the pant legs. And my officers tried to figure out how they could miss my leg and make those holes. And I got a letter from a buddy that was there, he got married after we came home, and he said, "I sure would like to have you meet my wife. I’ve been telling her all about you and what we did over there." Then he said, "Well, not quite everything." But he said, "I even told her about the seven holes in your pant leg."

Aaron Elson: Now, the German sergeant that was captured, he had smeared blood on his face?

Darrell Petty: He'd seen what was happening. He saw we weren’t taking any prisoners, his comrade was dead, and he just got some blood and smeared it on his face.

Aaron Elson: Was he wounded at all?

Darrell Petty: Not touched. He just lay down and played dead.

Aaron Elson: And somebody was going to shoot him, and then who said that they wanted to talk to him?

Darrell Petty: Sergeant Will was gonna kill him, and Lieutenant Kelso, he was our executive officer, he hollered at him, "Will, don’t you kill him, I want to talk to him."

Aaron Elson: And after they talked to him, then what happened?

Darrell Petty: Then he went back to a prisoner of war compound. But, oh yeah, we called it Machine Gun Hill. We figured we were kind of justified in doing that. The official number is Hill 451.

(Coming soon: Darrell Petty, Part 2)

Read more interviews like this in "A Mile in Their Shoes," by Aaron Elson, available in our eBay store as well as at amazon.com (where you can order a "used" copy directly from the author at a discounted price). It is also available as an e-Book for Amazon's Kindle.

- - - From Oral History Audiobooks: Encounters With General Patton

The Tanker Tapes From D-Day to the Bulge The D-Day Tapes From Chi Chi Press: Tanks for the Memories A Mile in Their Shoes Got Kindle? Conversations With Veterans of D-Day Nine Lives: An Oral History They Were All Young Kids

Published on September 22, 2012 18:36

September 11, 2012

"You Could Build 88s, Why Couldn't You Kill Lice?"

Walter "Red" Rose Back in the 1990s, I would take my Sony Walkman style tape recorder with me to reunions and mini-reunions of the 712th Tank Battalion. Sometimes a group of veterans would be sitting around a table in the hospitality room, and I would record the conversation.

Walter "Red" Rose Back in the 1990s, I would take my Sony Walkman style tape recorder with me to reunions and mini-reunions of the 712th Tank Battalion. Sometimes a group of veterans would be sitting around a table in the hospitality room, and I would record the conversation.When I wrote my first book, "Tanks for the Memories: An Oral History of the 712th Tank Battalion," I transcribed many of those recordings, as well as tapes of individual interviews. There was a lot of background noise on some of the hospitality room recordings, which rendered them difficult to use in an audiobook until a better sound engineer than I processes them, so the transcriptions pretty much languished in a series of computer files, along with backups of most of them in various places. Some of the backups are on floppy disks, that's how old they are.

I spent the summer writing two books. The first, "Conversations With Veterans of D-Day," is available for Amazon's Kindle, but I'll probably withdraw it soon to rewrite the introduction and add some more photos I found, and then release it in a print version as well. The second, "Inside the Turret: The 712th Tank Battalion in World War II," will be published by a prestigious British firm, "Fonthill Media," in the near future.

Much of the research for both books involved reviewing the transcripts of my interviews and hospitality room sessions, some of which I hadn't looked at in years. Over the next few blog posts I plan to include some excerpts of those conversations, which, if my own reaction is any indication, make for great reading.

Here's an excerpt from a conversation I recorded on Jan. 26, 1995, at the battalion's "mini-reunion" in Bradenton, Fla. Every year the 712th would hold a formal reunion, usually somewhere in the Midwest because a large portion of its personnel came from the central states. But as the veterans began to retire, with many of them moving to Florida or spending the winter there, a small group of them got together and held a less-formal mini-reunion. Jack Roland, a veteran of Headquarters Company whom I never met because he passed away before I started doing this, moved to Bradenton for health reasons and soon became the mayor of Bradenton. Sam Adair, another veteran I never had the fortune of meeting, organized the first mini or two elsewhere in Florida, but Roland was able to get the group a good deal at a local Days Inn on Route 41, and the minis were held there until the motel changed hands and the perks evaporated. But because their time in the battalion was so special to so many veterans, some of them would come from all over the country -- Forrest Dixon from Munith, Mich., Jim Flowers from Richardson, Texas -- so they could be with the other veterans two weekends a year instead of just one.

Walter "Red" Rose, who was a sergeant in Service Company, would drive down from Ahoskie, N.C., with his wife Dorothy and stay in a camper in the parking lot. Clegg "Doc" Caffery, who wasn't a doctor but owned a plantation in Louisiana, was descended from a Caffery who went down the Cumberland River with Andrew Jackson, and took over the kitchen at the motel to make a big pot of shrimp etouffe for the Saturday night dinner, was another.

There will be more in future posts, but here is an excerpt from a conversation I recorded at the 1995 mini. It begins with Red Rose relating a conversation he had during a trip to Germany:

Red Rose: I talked with some of the Germans up there, and they all say that they weren't guilty, it was another organization. See, they had so many organizations over there, each one wants to blame it on the other one, all the atrocities. There's an old fellow living there in Freiburg, Germany, and I'm sitting there talking to him. He was a prisoner of war in Ahoskie. I said, "Let me ask you, why did you Germans let Hitler get ahold of you, and the Nazi party, like you did? You're smart people. Why?"

He said, "Rose. I can remember as an 11- or 12-year-old, I was hungry." He said, "When you get hungry, you're gonna follow anything." And he said, "I remember seeing those boxes coming down with bouillion." And they said "If you join our party, here's what you will have." Well, they were against the Jews, they were against the communists, they were against anything if you wasn't pure German. And they just kept going. Finally they got ahold of him. And he said he was a great believer in the beginning. But he said, "It was like this. Once they got you by the throat," he said one day, he closed his fingers like that, "you couldn't get out. And you didn't want to talk to nobody. Even your best friend, if you didn't like what was going on, they're like to come and get you tomorrow night." And he said, "We lived under a noose, a complete noose, regardless of whether we wanted to or not."

Doc Caffery: Everybody was afraid.

Red Rose: Everybody was afraid. And he said you didn't have no friends. You couldn't go to a friend and say, "Let's do something." You didn't know who you was talking to. You didn't know whether you was talking to a Gestapo agent, or what. That's the way he put it. He said "I never fired..."

Doc Caffery: They didn't want to trust anybody.

Red Rose: No. And he said, "I'll tell you something else. The happiest day was when I got captured." And he said, "I'll tell you something else. When you all invaded Normandy, I never fired a gun." And he said, "I didn't fear all the shells near as bad as I did the lice." He said, "Hell, I was eat up with lice. We couldn't control it. We was down in there being eat up." And he said, just to get out from underneath was ... Isn't that something, the lice?

I said, "You could build 88s, why couldn't you kill lice?"

He said, "That's what I don't know. We could build some of the best guns, but we couldn't kill lice." He said they had leather shoes, and leather coats, and when they got damp, that created those lice.

Doc Caffery: And they didn't have insecticide, no DDT or anything like that.

Red Rose: No. He said, "A lot of times I thought about just running out the top, letting one of these shells hit me."

Doc Caffery: Because he was so full of lice (laughing). That was a condition to get into, huh?

Forrest Dixon: Doc, how are you? [While Clegg "Doc" Caffery wasn't a doctor, Jack "Doc" Reiff was: He was one of the battalion's two medical officers. He was born in Muskogie, Okla., but was retired and living in Lady Lake, Fla.]

Doc Caffery: Doc Reiff.

Doc Reiff: Okay.

(Some of the tape was not transcribed, probably due to excessive background noise, but here the conversation, which picks up in mid-sentence, has shifted to the voyage across the Atlantic aboard the SS Exchequer)

Red Rose: ...after it went off, he started spewing...

Aaron Elson: Who was this, Captain Laing?

Red Rose: Captain Laing. That's what we went through over there.

Aaron Elson: In the middle of a speech?

Red Rose: Yeah, he was telling us what we should do if we got captured. I thought I was gonna do real good, I was standing on the deck, and here comes up out of the kitchen a big tub of chitlins. And I was trying my best to keep from getting sick. He started dumping them overboard and I seen 'em fly, and from that day on I was sick, too. Chitlins. Can you imagine dumping right beside an old seasick boy. Ohh, lord. Somebody said "Sink this sonofabitch, I don't care!"

I said, "Well, buddy, I feel about like you do, but I don't want to go down right now." That was Joseph Hopper. He was the one that hollered, I'll never forget those words, here I am, sick as a dog, and he said "Sink this sonofabitch, I don't care."

Doc Reiff: The ship was pitching end to end and tossing straight up and down, and the captain said, "But it'll never break apart in the middle like those Liberty ships." And I thought, oh shit.

Joe Fetsch: I took heat on that boat. The Exchequer was built in Baltimore. And everybody said, "Christ, you come from there, look at this lousy ship."

Aaron Elson: Was that a Liberty ship?

Doc Reiff: No, it wasn't. But that fellow, he was really proud of it.

Joe Fetsch: The sister ship was ahead of us, and he was doing this and that and everything else in that water.

Doc Reiff: The captain was really proud of the ship. He said it would never break apart in the middle -- we'd never thought about that (laughing) -- like Liberty ships. Something else to worry about. But talk about being sick. I don't know where the Army got the idea, but they had to have that short-arm physical inspection, and here I was, looking at guy's mouth, skin, seeing if he had a skin rash, or any discharge. And the ship was going all this way and that. (laughing).

- - -

Got Kindle? All of my books are available for Amazon's Kindle at greatly reduced prices. Amazon also has a free Kindle "app" that you can download to your computer, tablet or smart phone so as to be able to order Kindle books. And if you're a fan, I sure could use some reader reviews!

Tanks for the Memories

A Mile in Their Shoes

Conversations With Veterans of D-Day

Nine Lives

They Were All Young Kids

Also:

Love Company, by John Khoury (edited by Aaron Elson)

Follies of a Navy Chaplain, by Connell J. Maguire (published by Aaron Elson)

Published on September 11, 2012 10:40

July 28, 2012

General Patton at the Crossroads

Suella and Russell Loop

Suella and Russell LoopIn my Oral History Audio CD "Encounters With General Patton," I included an anecdote related by Russell Loop when I interviewed him at his home in Indianola, Illinois, on Oct. 24, 1993.

I might note that I almost didn't get to interview Loop, who, in his mid 70s at the time, was a farmer. I have somehow managed to get lost in almost every state in the nation. I even got lost in a parking lot, but if you've ever been to the Drawbridge Estate in Fort Mitchell, Ky., you might not be judgmental. And once in my travels when I was visiting my brother in Minneapolis and proceeded to visit a cousin in Madison, Wisconsin, I got off the highway to get a cup of coffee and managed to get back on headed west. The first few times I saw signs telling me how many miles it was to St. Paul, I thought, gee, I didn't know there was a St. Paul in Wisconsin.

I can't think of a time, however, when I've been more lost than when I was on my way to visit Russell Loop and hs wife, Suella.

He told me to get off the highway, look for a certain convenience store, take a road all the way to the end, make a right, and take that road to the end.

This was farm country, and somehow the first road I took didn't end until I was probably in the next county, but what did I know, there was the end of the road and I made my right and drove for several miles until I finally came to a house with the number of Russell's house, and it's not like there were any streets signs along the way. I rang the buzzer, and a young couple with a baby came to the door. This must be Russell's son or daughter and grandchild, I thought. Except they had no idea who I was talking about. But they explained that Indianola was back the way I came, so I doubled back to the convenience store and called Russell, and this time I got it right.

All that, of course, is not on the CD. What is on the CD is the part that follows my asking Russell "Did you ever see Patton, up close?"

"Yes," he said. "Real close. We had just pulled up on a four-way crossroad, which was a hard road, and pretty nice roads for back that time. And we had not met any resistance there. But we had just pulled off and was waiting for further orders, and here comes Patton and his jeep, and his driver, and he just more or less walked by the officers and went around and shook hands and talked with nearly every one of the enlisted men. And while he was there, there was a German plane that strafed that crossroads both ways, twice. And he just looked up and said 'They must know I'm here.'

"That's all he said, about that. But what he wanted to know was, 'Are you getting plenty to eat? Are you getting enough ammunition and gasoline? And is there anything that I can do to make it better?'

"And of course we all said 'Yes, send us home.'" -- Russell kind of laughed when he said that -- "But I did, I got to shake hands with him on the front line.

"He was I suppose by far the best officer we had. He got the job done. He didn't give them time to get set up and ready for us. He kept them out of bounds. And I think that was the whole deal, really, myself. I think that's the reason we got as far as we did as quick as we did. Of course, we were clear across Germany and Czechoslovakia when the war was over."

Another time I got lost was in Albuquerque, New Mexico, looking for the home of Lex Obrient. Come to think of it, this one may even beat my search for Russell Loop, because I never did find Obrient's home; he lived in a cul de sac in one of the communities that seem to ring Albuquerque, and I drove around for a couple of hours before finally abandoning my quest. This, too, was in 1992 or 1993. I did keep in touch with Obrient's son, however, and in 1999 when I went out to Albuquerque to interview Vincent "Mike" McKinney, whose interview is included in my audiobook "The D-Day Tapes" and my Kindle book "Conversations With D-Day Veterans," I finally found Obrient's house.

It wasn't until today, however, 13 years after that interview, while reviewing material for my forthcoming book "The Armoured Fist," which will be published by Fonthill Media, that I realized that Lieutenant Obrient (he later was a colonel with an engineering unit in Korea) was Loop's platoon leader for a while. Obrient was in D Company, the 712th Tank Battalion's so-called "light tank" company, while Loop was in C Company and my principal reason for interviewing him was because he was one of the tankers involved in the battle at Pfaffenheck, Germany, on March 16, 1945. But Loop started out as a gunner in D Company and later transferred to C Company's second platoon.

As in many of my interviews, the subject of General Patton came up, and Obrient related one of the many colorful anecdotes I've been fortunate about front line encounters with Patton.

"At Mortain," Obrient said, "my platoon was right there at the crossroads at Mortain. Lieutenant Godfrey's platoon went around where the cross-section was and he went down that way, and then Harry Coe (Eugene Godfrey and Coe were the other D Company platoon leaders at the time) went down even further. So we're sitting there, and just playing a flank guard for anything that was coming because they were getting ready to move the 2nd Armored, I was told, the 2nd Armored Division was getting ready to come through. But before that, here comes Patton down the road with his whole staff of officers, and three or four jeeps behind him. So he’s coming my way, and when I got up there and I reported to him, he returned it and said hi, and shook hands real quick, but he didn’t want to talk to me. He wanted to talk to my sergeants with the other tanks. And what he wanted to know was if they really understood what was going on. And he was very satisfied with what he heard. I mean, they told him, we’re here, and this is what we’re here for, and this is what we’re doing. He immediately left and I called on the radio and I told Gene about this. I said, 'Gene, you’re about to have some very special company. It won’t be more than two or three minutes.'

And he said 'Thanks.'

Sure enough, Patton went on down there, he talked to Gene, and he went down and talked to Coe, as I remember. But then we saw him come back. And then a funny thing happened. We got strafed. I don’t know how the Germans would have found this out, but I kind of feel like somebody had tipped them off that hey, I guess you couldn’t miss it, I mean gee, Patton with his brilliant, shiny helmet and dressed to perfection. Okay, that’s the second time I met Patton. I’m glad you brought that up. That’s what happened. Did Andy (Schiffler) tell you anything about that?"

"No," I said. "You know who told me about that? Russell Loop. Do you remember him? He transferred to C Company, but he said that once Patton came up and spoke to the enlisted men. He was a sergeant, and you know, he bypassed the officers. So that would have to be the same, because he started out in D Company."

"Russell Loop?" Obrient said.

"Loop," I said, "From Indianola, Illinois."

"Ah, yes, I remember him," Obrient said. "But you know something else that I don't know if Andy told you about, there was a woman there with her children in a house close by. And of course, this is one thing Patton insisted on, "Don’t you take any food from any of these people. You have what you need. Leave it alone." So I felt real sorry for this woman and her children. And we had fruit, we had some apples and we had oranges, and those children, they hadn’t seen any candy at all. Well of course all the candy we had was that D-bar, that highly concentrated chocolate, so I tried to tell her, listen, these are for your children, because I knew they hadn’t had any food there, I was told that they hadn’t had any oranges or apples, they didn’t know anything about any of that. And above all, they hadn’t had any chocolate. So I think Andy was one of them that gave her the chocolate.

"So you know what she did? She was so grateful, she went and killed a couple of chickens, and boy, I thought, no ma’am, don’t do that, uh-uh. But she did anyway, and they came out there, and this is just before Patton showed up. So what we did, they had it on one of these oblong plates and cut up, I said 'Jesus Christ, we’re all gonna be in trouble.' So we took it, and thank God he didn’t get close enough to notice it, but we pushed it in under the bogey wheels and the track and covered it with jackets and so forth. Of course he wasn’t there long. Thank God he wasn’t. He just was in and out. So when he got out of there, I took that chicken and said, "Ma’am, please, for God sake, take that back, don’t do that." So we made her take it back. But if he’d have found out, I hate to think what would have happened. But he was real fast. He came up, and I bet he was gone in less than a minute and a half. But that’s what he wanted to do. He wanted to talk to the sergeants and the other enlisted men that he could talk to.

"So that’s the second time I saw General Patton, right there. The first time was on the hills in England, and then the second time I saw him was there. And then we saw him again up in the Battle of the Bulge, but I didn’t really get to say anything to him. I just saw him, and he went right on. It was fast. And then the last time I saw him, the war was over and we were in the theater at Amberg, and he came around and he talked oh, maybe ten, fifteen minutes, with as many troopers as could get in that theater. That was the last time I saw him, of course you know what happened to him after that at Mainz. No. Yeah, Mainz, that’s where it was [actually near Mannheim]. He was in his staff car and he was waiting for a train to go by, and these guys had been drinking, and they drove a two and a half ton truck into the back of him and broke his neck. You know that part, I’m sure."

Watch for more information about and excerpts from my forthcoming book, "The Armoured Fist," from Fonthill Media. That's Armour with a "u" because Fonthill is a British publisher, besides, I do seem to have a small following in England and Australia, although I have no idea how Australians spell armor.

My original Oral History Audiobook "The D-Day Tapes" is available from Amazon.com for download or on CD from eBay, and "Conversations With Veterans of D-Day" is available for Amazon Kindle.

- - - From Oral History Audiobooks: Encounters With General Patton

The Tanker Tapes From D-Day to the Bulge The D-Day Tapes From Chi Chi Press: Tanks for the Memories A Mile in Their Shoes Got Kindle? Conversations With Veterans of D-Day Nine Lives: An Oral History They Were All Young Kids

Published on July 28, 2012 08:17