Aaron Elson's Blog, page 19

March 22, 2013

Aaron Elson Interviews Himself

Now that my new book is available (official release date, April 16), I thought it would be way cool to do one of those blog tours. Then I discovered that there's like this blog tour circuit, and there are blog tour brokers and bloggers who charge money, albeit not a heck of a lot, for you to fill out a boilerplate interview template. So I decided phooey, I can just as easily interview myself. At least I read the book. Q. Good afternoon. Thank you for stopping by.

Now that my new book is available (official release date, April 16), I thought it would be way cool to do one of those blog tours. Then I discovered that there's like this blog tour circuit, and there are blog tour brokers and bloggers who charge money, albeit not a heck of a lot, for you to fill out a boilerplate interview template. So I decided phooey, I can just as easily interview myself. At least I read the book. Q. Good afternoon. Thank you for stopping by.A. What do you mean? I live here.

Q. In that case, I wouldn’t mind a cup of coffee.

A. I only serve tea.

Q. That's right. Your book is being published in England.

A. Yes. Would like a crumpet with that?

Q. Thank you. State your name for the record, please.

A. Aaron Elson

Q. No middle initial?

A. C for Charles. That was one of my great-grandfathers. Aaron was another. Aaron was also my grandfather’s middle name, Milton Aaron Reder. He wasn’t a very good grandfather, but he was a doctor who was much-loved by his patients.

Q. Why do you say that?

A. He was in his office seven days a week, twelve hours a day and six hours each on Saturday and Sunday. He outlived all three of his children and was 92 when he died.

Q. Was he a veteran?

A. He was a doctor in World War II. It’s one of my great failures as an oral historian that I never got him to tell me about his experiences except for one story. He was on a beach treating a soldier who had an injured leg when some dirt came flying into the foxhole or wherever he was doing the treating. He said he shouted for the person to quit throwing dirt on his patient, and the person he yelled at turned out to be General Patton. I don’t know if that’s true or not, but knowing my grandfather it probably was. He may have been traumatized by the war, because he lost his voice – it was a psychological thing, there was nothing wrong with his vocal chords – and could only speak in a hoarse whisper.

Q. Was your father a veteran?

A. Yes, he was. That’s what got me started doing oral history. He was a wonderful storyteller, but he was in and out of hospitals the last few years of his life – gout, prostate problems, heart attacks, a quadruple bypass. He had a heart attack when I was 30 years old, and I realized I’d forgotten most of the stories he told about World War II. So I bought a little Sony recording Walkman and was going to take it with me when I went to visit him in the hospital. I forgot the tape recorder, he got out of the hospital, and died two weeks later. That was in 1980. Seven years later I discovered a newsletter addressed to him from the 712th Tank Battalion Association – that’s the outfit my new book is about.

Q. What did you do with the newsletter?

A. I wrote to its editor, and asked him to put a notice in the next issue saying if anybody remembered a Lieutenant Elson, would they get in touch with me?

Q. And what happened?

A. Almost by return mail I got a letter from Sam MacFarland. He said, “I didn’t know your father, but the battalion is having a reunion. It’s too late for the next newsletter, but if you come to the reunion, I’ll take you around and we’ll see if we can find anyone who remembers your dad.”

Q. Did you go?

A. Yes I did.

Q. And what happened?

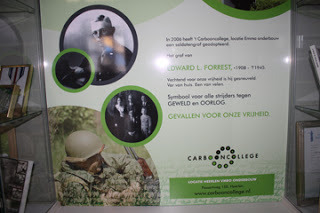

A. Sam and I found three veterans who remembered my dad. I explained that I remembered very little from his stories – the name of a fellow lieutenant, Ed Forrest, who was killed, and that my dad said there was something about Ed that gave him the impression Ed either didn’t want or didn’t expect to come home. His evidence was that Ed readily volunteered for an exceptionally dangerous mission in Normandy. He speculated that Ed’s father may have been a minister who didn’t approve of him going off to war.

Q. Was that the case?

A. Actually, no. Years later I would learn that Ed’s father was an alcoholic, his mother committed suicide, he fought with his father and a minister took him in when he was 14 and raised him like a son. The minister, it turns out, was a chaplain in World War I and couldn’t have been prouder of Ed when he became a lieutenant.

Q. My goodness. How did you learn all that?

A. I interviewed Ed’s brother, as well as the woman he likely would have married if he came back. I read an unpublished memoir written by his sister, and a diary left by the priest.

Q. What else did you know about your father’s experiences?

A. He said he replaced the first lieutenant in the battalion to be killed. He was wounded in Normandy and again in December. The December wound was in a place called Dillingen. Almost everybody at that reunion had a story about Dillingen. I was like Wow.

Q. What led you to morph from reconstructing your father’s experiences to learning about the other veterans’ experiences.

A. Morph, that’s a good word. Some of the veterans asked if I’d like to go to lunch with them. One of them was telling a story on the way to the parking lot, and when we got to his car, he opened the door, but it was about five minutes before anybody got in because he had to finish the story. I entered the hospitality room in the middle of another veteran telling a story and listened to the end, kind of like when you go late to a movie and miss the beginning but still get caught up in the action. Later I asked the veteran to tell me the story from the start.

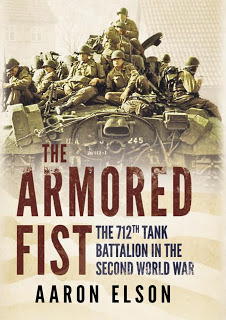

Q. Why did you write “The Armored Fist”?

A. When I began recording the veterans’ stories, I didn’t know squat. I thought the Battle of the Bulge was an American offensive (it wasn’t. It was a German counteroffensive). I looked at the battalion’s record – 1,165 men, 3 Distinguished Service Crosses, 56 Silver Stars, 465 Bronze Stars, 498 Purple Hearts, three Presidential Unit Citations – and the only thing I recognized was the Purple Hearts, because my father got two of them. As I recorded the stories of its veterans, I began to realize, this outfit deserves its place in history.

Q. What makes your book different from many other books of military history.

A. You should say “many other great books of military history.” There are more great books of military history than you can shake a stick at. But I believe my book is, in some ways, unusual. When I was writing my first book, I called the Military Book Club, and the person I spoke to said there were two things readers of military history wanted: maps and pictures. So I put a couple of maps and a bunch of pictures in my first book, “Tanks for the Memories,” which I self-published. But the truth is, I couldn’t read a map if it led to a pot of gold. I’ve been lost in almost every state in the nation. There are no maps in “The Armored Fist.” There are a lot of pictures, but the pictures aren’t so big that they dwarf the text.

Q. You’ve said “This isn’t your father’s military history.” Is that because it’s your father’s story?

A. No. I say that because it has some unusual sources. Many books about World War II draw on morning reports, after action reports, oral history interviews, previously published books, etc., etc. I have some of that in “The Armored Fist,” but I also have excerpts from the diary of the priest who raised Ed Forrest. I draw on letters and high school essays of a young replacement who was killed. I quote from a memoir written by the sister of a soldier. I’ve tried to show a deeply human side of the war.

Q. What do you plan to do next?

A. My publisher wants me to write a book about the Kassel Mission, one of the most spectacular air battles of World War II. It’s also one of the great little known stories of the war.

Q. Well, that about wraps it up. Is there anything I’m forgetting to ask.

A. Yes. Now that “The Armored Fist” is out, you could ask your readers to consider donating to my Indiegogo campaign, so that I can launch the “Yanks in Tanks Tour.”

Q. I certainly will. Please check out Aaron Elson's Oral History Audiobooks Indiegogo crowdfunding campaign.

A. And if there are any other authors reading this who'd like to interview themselves, email me and I'll be happy to post your interview on my blog.

Q. One more thing. Is there an excerpt from "The Armored Fist" available?

A. There'll be one in my next blog post. Oh, one more thing.

Q. What's that?

A. I'd like to recite a little poem:

At the top of this page

On the right hand side

You'll see some little

icons

Hit the Share button

Hit the Tweet

Thank you

Q. That doesn't rhyme.

A. It's free verse.

Q. It is?

A. It didn't cost anything, did it?

- - -

Published on March 22, 2013 15:59

March 19, 2013

The Mark of a True Soldier (Pfaffenheck, Part 3)

(Pfaffenheck, Part 1) (Pfaffenheck, Part 2) I've only watched the first two episodes of "Band of Brothers," and that was several years ago, but when I did, one scene jumped out at me. And wouldn't you know, the scene is on YouTube, so that I was able to refresh my memory this morning. It's the scene in which the paratroopers find a dead German soldier wearing an edelweiss, the "mountain flower," which one of them remarks is the mark of a true soldier. The first time I saw the scene, I was like, "What's an edelweiss doing here?" When I traveled to the village of Pfaffenheck in 1995, I learned that the edelweiss was the symbol of the 6th SS Mountain Division North, whose soldiers were ski troops and spent a good part of the war in Finland. The "mountain flower" only grows above 10,000 feet, and I think one of the soldiers in "Band of Brothers" remarks that it was the mark of a true soldier because that soldier had to climb a mountain to pick one. The last few months my book "A Mile in Their Shoes" has been above the tree line in the Amazon Kindle rankings in three different categories -- Armored Vehicles, Naval, and Veterans -- and one of the books that has been up there for eons is titled "The Lions of Carentan." It's about the 6th SS Falschirmjager Division, which was in Normandy. The dead German soldier in the "Band of Brothers scene" was from the 6th Falschirmjagers. I don't know if they had an edelweiss for their symbol or if that was a Spielbergian touch, but for me it was an aha! moment, as is just about any moment when I recognize a personal connection to a scene in a documentary, movie or book. I'm not much of a photographer, but I've always been captivated by the photo I took at the beginning of this entry of an edelweiss -- not a real one -- on the inside window of the BMW of the German veteran who acted as one of my two interpreters. I can't name him because he wrote a book in English titled "Black Edelweiss" under the pseudonym Jochen Voss. Voss did not take part in the battle at Pfaffenheck. After the fidgety-nerved tank gunner fired those five shots into his machine gun position, he was taken prisoner a week before Pfaffenheck at Wingen as the 6th SS Gebirgsjagers -- a gebirg is a mountain, whereas a fallschirm falls out of the sky, or something like that -- worked their way north from the Vosges. Nor was the other interpreter, Wolf Zoepf, who also wrote a book, titled "Seven Days in January," as he was captured during Operation Northwind. Zoepf passed away the week his book came out. A number of interesting things occurred when I went to Pfaffenheck the following year for the Germans' reunion and ceremony. On the second day, Voss said to me that after a discussion among the association's leadership, they decided it would be okay to ask me about something. One of the villagers in Pfaffenheck some time ago had told the German veterans about an incident in which the tankers in Pfaffenheck made a badly wounded German march in front of a tank as they approached the village. Voss wanted to know if I had ever heard of such an incident. I told him I would look into it. I only had to look as far as my 1992 interview with Bob Rossi, the loader in Otha Martin's tank, commanded by Jack Green, in which he described the battle without knowing the name of the town.

"About that time, we're coming down the road, and there's a German soldier laying on the side of the road, he's about cut in half on a stretcher. And I remember, Loop's tank was in front of us, we were coming behind him, and the German was like waving from the stretcher for us not to run over him. I don't think we would have anyway, I don't think I would, I know we wouldn't. So we went into the town, and there was a house, and they made a red cross on a sheet with blood, the Germans, in blood they made a red cross hanging out there, and there were German wounded and German prisoners lined up along a little brick wall there in front of the house.There are enough elements in this description to indicate it took place after but not in Pfaffenheck. Lieutenant Fuller's platoon approached the village through an orchard and didn't take the road. (It may have been the day before, as they approached Udenhausen.) All of the participants are deceased, so I can no longer investigate further. But considering the character of some members of the platoon, such as Jack Green, and even the feelings at the time of soldiers I only encountered as gentle elderly men, I would say it was possible such an incident occurred. I never did tell Voss of my suspicions. A somewhat more humorous event occurred during the German veterans' banquet on the last night of the reunion. The first year I went, the banquet was a luncheon in the early afternoon and was in some kind of municipal hall. The second year it was in the evening, it was 1996, the beer was flowing pretty freely, and following the dinner the room burst into several marching songs. It was quite entertaining. And then one veteran came to the table where I was sitting with Voss and a couple of other veterans, and he was very animated, he wanted to tell me something, only he didn't speak English, so he just poured it out in German, and I could tell Voss was just the least little bit uncomfortable at what he was hearing. He did, however, give me a synopsis of what was said. This veteran had just joined the division as a replacement, I guess he was about 18 years old, and Pfaffenheck was his first battle. He was in a house at the end of the village, one of three I think that were occupied by the Germans, and when he saw the tanks approaching and firing their big guns, he crapped in his pants. Even after all these years, there was something unspoken in Voss' reaction to this story that seemed to project disdain. I haven't spoken with Jochen since, but my two German Facebook friends -- Holger and Thorsten -- who I supplied with copies of my German interviews, told me he's still living and they've now been in touch with him. So bear with me, I'm sure you haven't heard the last of Pfaffenheck, which also is described in my new book, "The Armored Fist," due to be released on April 16.

"So with that, Loop went back to bring this guy in, the wounded German, and he makes the guy walk in all the way. The guy is just walking hunched over, just holding his gut, he's in bad shape. And he gets to that wall, and he's leaning on the wall. In the meantime, one of our medics motions to two German soldier prisoners to help with the wounded. [Jack] Green thinks that these two guys are trying to take off, and he grabs the one Kraut and he hit him on the head, he kept banging him on the head with a tommy gun clip, he split his head open, and I'm going "Hey Green, for Chrissakes, stop, Green!" He was a mean sonofabitch."

Published on March 19, 2013 10:30

March 16, 2013

"Goering's Gifts" (Pfaffenheck, Part 2)

Fritz Gehringer, a veteran of the 6th SS

Fritz Gehringer, a veteran of the 6th SSMountain Division North, standing in

1995 beside the tree where he was wounded

five times on March 16, 1945.

"Don't go. You'll only humanize them."

That was my supervisor talking when I told her where I was going on my vacation in 1995.

Over the years, as I gathered the stories of the 712th Tank Battalion, I, myself, became the subject of a handful of stories, like the time, having heard Jim Flowers tell the story of Hill 122 several times, I supplied him with a detail he seemed to be grasping for and he blurted, "Who's telling this story, me or you?" Or the time, knowing the answer but not nearly suspecting the force with which it would be delivered, I asked Otha Martin if he was at Pfaffenheck. "Pfaffenheck," he repeated coldly, fixing me with a stare. "The Sixteenth day of March in '45. I was there. I can tell you every man that was there." And he proceeded, with remarkable accuracy, to name the five crew members of each of the five tanks in the second platoon of C Company, including his own, that took part in the battle.

My own interest in Pfaffenheck goes back to 1987, the year I first attended a reunion of the 712th, where I met two sisters, Maxine Wolfe Zirkle and Madeline Wolfe Litten -- twins -- whose brother Billy was killed at Pfaffenheck when they were 16 years old. Billy was 18. There are some pretty remarkable twists to the story, but long story short, John Zimmer, a member of Billy's platoon, had contacted the sisters so that he could deliver a plaque in Billy's memory. Thus started a journey of discovery for the sisters. Because I was beginning my own journey of discovery at about the same time, the two journeys crossed paths. In 1992 I interviewed Bob Rossi, who described the battle at Pfaffenheck although neither he nor I knew it was Pfaffenheck he was talking about. The newsletter reprinted a letter written by Byrl Rudd, the platoon sergeant, to Ray Griffin, the newsletter editor, describing the battle. And Rossi showed me a copy of a letter written by Lt. Francis "Snuffy" Fuller to Hubert Wolfe, Billy's older brother, who was in the 78th Infantry Division. Hubert never showed the letter to his family, and didn't tell his sisters about it until he was on his deathbed.

As I gathered the stories of the battalion, I always asked about Pfaffenheck. And then in 1995, one of the veterans told me there was a notice in the 90th Infantry Division newsletter saying there would be a ceremony in Pfaffenheck commemorating the 50th anniversary of the battle.

I wrote to the person who sent in the announcement and said that I wasn't a veteran but that I had interviewed several survivors of the tank battalion that fought there, and that I would like to come to the ceremony.

I got quite a shock when the reply came: I would be very welcome to come, only it was not being put on by the village, but by the Germans who fought there.

Not only that, but this was an SS outfit. And I'm a Jewish kid from New York. At least I was a kid some 50 years ago, or 35 years before this ceremony was to take place.

Needless to say, the letter gave me pause. Byrl Rudd's letter described the SS troops his platoon encountered as "fanatical," and Fuller's letter said pretty much the same, indicating that they fought almost to the last man. On the other hand, I spoke with a 90th Division veteran who was captured by the 6th SS Mountain Division, Reuel Long, who lived in Minnesota. He wanted to go to the ceremony but couldn't get a low-cost airfare and had to cancel. But he said that he was captured at Pfaffenheck and his captors treated him very well and with respect; it was not until he was sent to the rear that he suffered abuse. And just by coincidence as I was reading a book called "Raid!" about the attempt to free General Patton's son-in-law from a prison camp, I came across an account of another soldier who went out of his way to say that the 6th SS Mountain Division treated him well when he was captured.

The liaison, whom I can't name because he wrote a book about his experiences under a pseudonym, stressed that the division was fighting in Finland for much of the war and was not in any of the areas where atrocities attributed to the SS took place. He said that it was basically an elite fighting unit. When I pointed out that the couple of references I'd seen to the battle described them as fanatical, he said they knew the war was lost but that they thought that by continuing to fight, they could gain time for a negotiated settlement, and that they were fanatical not in their devotion to Hitler but in their devotion to the comrades beside whom they'd been fighting for three or more years. And he wrote a letter to Paul Wannemacher, the battalion association president, saying that he owed his survival to the fidgety trigger finger of a tank gunner, who fired five rounds at almost point blank range into his machine gun position, and yet he survived. (There was a touch of humor when he wrote this, but in his book the scene is absolutely terrifying).

In a way, I guess, my supervisor was right. I arrived at Pfaffenheck a day before my hosts, and encountered two of the German veterans, Fritz Gehringer and I don't remember the other's name. Because we were the only three there, they took me on a little sightseeing tour, the highlight of which was the tree beside which Gehringer was standing when he was struck by five bullets. He said to make matters worse, they were hollow point bullets, which were against the Geneva Convention.

As we stood by the tree and Gehringer posed for a picture, the other veteran said that they had just that morning broken into a house and found some food, and ate for the first time in a couple of days. And he said that the division had recently gotten a number of replacements, whom he said were described by the battle-hardened veterans of the war in Finland and the Vosges Mountains as "Goering's gifts" -- Luftwaffe trainees who were reassigned as infantry replacements

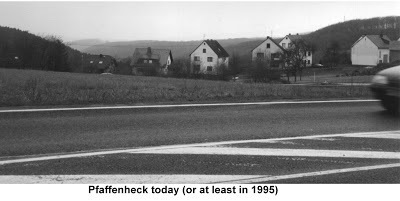

Pfaffenheck in 1995. Lieutenant Fuller's five tanks approached the village

Pfaffenheck in 1995. Lieutenant Fuller's five tanks approached the villagethrough what was then an orchard off to the left on March 16, 1945.. My supervisor was right. These were veterans of the Waffen SS, but to me they were humans. It was a strange feeling during the ceremony as I watched one of their veterans place a wreath in the cemetery at a monument dedicated to the anti-tank platoon, knowing that its weapons had knocked out three of Lieutenant Fuller's five tanks, killed four members of his platoon and wounded several others. And it was an even eerier feeling meeting the veteran who fired the antitank gun that struck Sergeant Hayward's tank, cutting off his legs -- he was later killed either by a sniper or machine gun fire as Fuller and his gunner, Russell Loop, tried to carry him between them to safety -- and either killing Billy Wolfe instantly or burning him to death inside the tank. It was a very strange feeling indeed, to learn at the banquet -- where my hosts set up a table for me to interview some of the veterans, with two of them acting as interpreters -- that the fellow who fired the antitank gun was in turn wounded -- likely by Sergeant Loop, who claimed to have gone up to the second story of a house, taken a rifle and picked off the members of the gun crew that disabled his tank -- and allowed to return to his family after getting back across the Rhine, and then, either weeks or months later, turned himself in so as to become a prisoner of war because he was unable to find work.

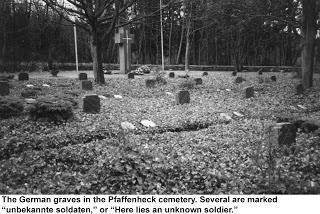

The grave marker of Gunther Degen, a battalion

The grave marker of Gunther Degen, a battalioncommander and Knight's Cross recipient, who

was killed at Pfaffenheck. When they held the ceremony in 1995, the Germans were expecting protests because anything to do with the Waffen SS was frowned upon in Germany. There was a significant police presence, but perhaps because it rained that day no protesters showed up. I returned from that reunion with about six hours of interviews in German with only the brief synopses by my two interpreters. I learned that the 1995 ceremony was unique only in that it marked the 50th anniversary of the battle, but that the veterans of the 6th SS Mountain Division North gathered in Pfaffenheck every year on the anniversary of the battle because 100 members of their division are buried in the village cemetery, and more are buried in the nearby town of Buchholz where there was another pitched battle, but one that to the best of my knowledge did not involve my father's tank battalion. When I went with the German veterans to the ceremony in Buchholz, they showed me an antiaircraft gun preserved in the village, that had been used against the ground forces. One of the men killed in Pfaffenheck, Sergeant Russell Harris, was struck in the head by a shell from a 40-millimeter antiaircraft gun. One thing I will say is that while I found the German veterans to be very human -- I remember overhearing something about Gehringer's wife suffering from depression, and Gehringer himself, who was the burgomeister of a medieval town called Rothenburg on the Tauber, would die the following year -- I can't say as much for some of the younger people who attended the ceremony/reunion. There was a young museum director I think from Koblenz who brought with him a rusty old pistol that had been found in the forest, and he was trying to confirm that it had belonged to Gunther Degen, and I very much sensed that he was more upset than most of the veterans that the Germans lost the war. And there were a couple of young what seemed to be neo-Nazis from Switzerland. I also sensed that my hosts were at least a little bit uncomfortable with what to some is the cult status of the Waffen SS. Those tapes -- and another three hours worth from 1996, when I returned to Pfaffenheck for their reunion, but more about that anon -- languished on a shelf until last year, when I heard from two men in Germany who belong to some sort of archeology club and were researching the events at Pfaffenheck. I was able to put them in touch with one of my hosts -- the other has since passed away -- and I sent them copies on CD of the interviews, which they promised to translate, although I haven't yet received the translations.

(Next: Edelweiss)

Published on March 16, 2013 12:02

March 15, 2013

Udenhausen (The Ides of March, Pfaffenheck, Part 1)

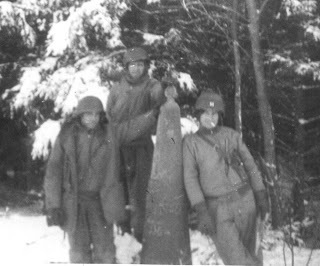

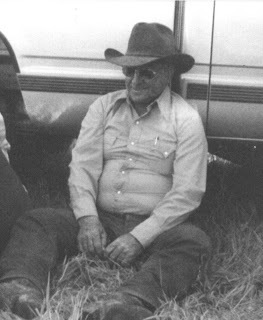

From left, Sgt. Byrl Rudd, Lt. Francis "Snuffy" Fuller and

From left, Sgt. Byrl Rudd, Lt. Francis "Snuffy" Fuller and Capt. Harlo J. "Jack" Sheppard at the dividing line between

Belgium and Luxembourg during the Battle of the Bulge.

Today is the Ides of March. I doubt, however, that any members of the second platoon, C Company, 712th Tank Battalion, had either Julius Caesar or William Shakespeare on their minds on March 15, 1945, in the village of Udenhausen, Germany, in the picturesque Rhine-Moselle Triangle, although they were about to play a role in a tragedy of their own. Ironically, an officer in the battalion's A Company, Morse Johnson, would go on after the war to a distinguished career as an attorney and philanthropist, and would become a founder of the Oxford Shakespeare Society, an organization dedicated to the belief that Shakespeare didn't exist. But A Company was elsewhere on March 15, 1945, and there were few if any highbrow intellectuals in the second platoon, C Company. There was Otha Martin, a burly tank commander from Leguire, Oklahoma, who was asked by the company commander, Capt. Harlo J. "Jack" Sheppard, to fill in for a gunner in a different tank that day and the next. There was Bob Rossi, a skinny 19-year-old loader from Jersey City, New Jersey, who was on loan from the third platoon after his tank was knocked out on Feb. 8 in Habscheid, Germany, and he was awaiting a replacement; and two replacements of two weeks duration in the platoon -- Billy Wolfe, age 18, of Edinburg, Virginia, in the Shenandoah Valley, and Jack Mantell, age I don't know, married with a wife and baby at home in Milwaukee, Wis. The platoon had been in combat since July 3, 1944, do the math, July, August, September, October, November, December, January, February, almost all of that time in near daily contact with the enemy, with the exception of about six weeks when General George S. Patton's vaunted 3rd Army was stalled at the Moselle River. There was Russell Loop, a farmer from Newman, Illinois, who was the gunner in the platoon leader's tank. The platoon leader was Lt. Francis "Snuffy" Fuller, who got his nickname when Wesley Haines, a member of the platoon who, according to Otha Martin, had "done imbibed him some," told Fuller, who was in his early thirties, that he looked "like Snuffy Smith in the comics." There was Russell Harris of Detroit, Michigan, a tank commander who joined the platoon after spending most of the war in a rear echelon position and hoped to get a promotion by getting some time in combat before the war ended, and Byrl Rudd, the platoon sergeant, a farmer from Ada, Oklahoma who'd been with the platoon through a succession of lieutenants. There was Wes Harrell, a tank driver from Stonewall, Oklahoma, who was nicknamed "Corporal Wac" because of the blousy uniform pants he liked to wear; and Koon Leong Moy, a loader from Boston who joined the platoon in September of 1944 in the same batch of replacements as Rossi. Moy quickly acquired the nickname "Chop Chop," and was sought after in vain by Sgt. Jim Warren, a tank commander in the third platoon, who wanted Moy to cook for him. Today that nickname would be interpreted as way politically incorrect, not to mention stereotypical, so imagine the response in the 1960s or '70s when Rossi was driving with his wife, Marie, through New York's Chinatown after visiting their daughter in New Jersey. Rossi thought he saw Moy crossing the street, and so he stopped his car, honked the horn, stuck his head out the window and yelled "Chop Chop! Chop Chop!" There was no response from the person he was calling to, but I can imagine he elicited a fair number of stares. There was Lloyd Heyward, another sergeant who joined the platoon as a replacement. Heyward was from Decker, Michigan, which is the town where Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols lived on a farm while they planned the Oklahoma City bombing; McVeigh was executed and Nichols is serving a life sentence. Coincidentally, Lambert Hiatt, an officer in the battalion's D Company, lived in Oklahoma City at the time of the bombing and felt his house shake when the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building was blown up on April 19, 1995, killing 168 people. There was Jack Green, a hard-drinking, rowdy tank commander who Don Knapp, a mild-mannered, sensitive tank commander, called the Mister Hyde to his own Doctor Jekyll. Green died shortly after the war of carbon monoxide poisoning when he was drinking in his car in North Carolina and fell asleep with the engine running. Knapp wasn't with the platoon on March 15, his place having been taken by Harris after the Battle of the Bulge. There was Guadalupe Valdivia, a Mexican-American, who was the assistant driver in the lieutenant's tank. And there was Carl Grey, the driver of Fuller's tank, who the lieutenant said reminded him of Li'l Abner. That puts Snuffy Smith and Li'l Abner in the platoon, but there was nothing comical about what was about to occur. Early in the morning of March 15, Bob Rossi was pulling guard duty in his tank in Udenhausen when he spotted some German soldiers emerging from the woods on the outskirts of town. He leaned down into the tank and whispered, according to Rossi, "Krauts! Krauts!" According to Otha Martin Rossi whispered "Heinies! Heinies!" Either way, Martin grabbed Rossi by the shoulders and yanked him into the turret, unintentionally slamming Rossi's head against the steel side of the tank. (Many years later, at a reunion, Rossi would tell Martin he thought Martin was trying to kill him. "I didn't have no problem with you," Martin said.) With Rossi out of the way, Martin grabbed his Thompson submachine gun, rose through the turret hatch, and began firing at a German in a floppy overcoat who was running toward his tank. "I buggered him up real bad," Martin would say at a battalion reunion in the early 1990s. "I don't know if he intended to throw a grenade or what." There was a brief firefight, but the Germans, who had no antitank guns -- a situation which would be greatly different 24 hours later in the neighboring village of Pfaffenheck -- retreated back into the woods. The Germans were from the 6th SS Mountain Division North, which spent much of the war fighting the Russians in Finland until the Finns signed an armistice with the Russians and ordered the Germans to leave the country. In order to do so they had to march 1,600 kilometers to the north, and then travel by ship to Denmark. Because they weren't proceeding fast enough on the march, the Finns, beside whom they'd been fighting for three years, attacked them from the rear and strafed them from the air, in order to prove to the Russians that they were serious about making the Germans leave. According to one of the veterans of the 11th Mountain Regiment, who would write a book about his experiences under a pseudonym, a battalion commander named Gunter Degen took his Finnish medals and left them nailed to a tree as the regiment proceeded north. According to Wikipedia, the division was supposed to take part in the Battle of the Bulge but didn't arrive in Denmark until Dec. 20, 1944, four days after the Bulge began. The division instead was sent to the Vosges mountains, where it took part in Operation Northwind, which broke out on New Year's Eve and is sometimes called the "other Battle of the Bulge." The division worked its way north, suffering significant attrition along the way, until it arrived in the vicinity of the cities of Trier and Koblenz and was told to buy time for other German units to escape across the Rhine. This is where it encountered the 90th Infantry Division and with it, the 712th Tank Battalion. After the second platoon helped the infantry secure the village of Udenhausen, it came under sporadic shelling, which caused the shingles to fall from the roofs of some of the houses. Jack Mantell, the recruit who'd been with the platoon for two weeks, was struck in the forehead by a falling shingle, but declined to go to an aid station for treatment, despite the sound advice of his more seasoned buddy Loop, who'd taken Mantell under his wing, to go back to the aid station and tell them that his head was killing him. Mantell and Loop had made one of those grim pacts so frequent in times of war: If Mantell were killed, Loop would visit his wife and child and tell them how he died, and if Loop were to be killed, Mantell would visit his parents and tell them how he died. Meanwhile, about two kilometers down the blacktop road, things were not going well for either side in the battle. A tank destroyer of the 773rd Tank Destroyer Battalion took a direct hit as it passed between two buildings in Pfaffenheck and burst into flames, killing all five of its crew members. Company K of the 358th Infantry Regiment was absorbing heavy casualties, while on the outskirts of town, the 11th Regiment of the 6th SS Mountain Division North was making a last stand at what would come to be known in the division's annals as the Schiebegeich Farm. It was there that Gunter Degen, the 26-year-old battalion commander who left his Finnish medals on a tree and who was a recipient of the Knight's Cross, was killed.

(Next: "Goering's Gifts") Please help support Oral History Audiobooks

Like Oral History Audiobooks on Facebook

Get information on ordering "The Armored Fist," by Aaron Elson (write "Armored Fist" in the subject line)

Published on March 15, 2013 14:12

March 9, 2013

The Iron Cross and a Three-Day Pass

Oral History Audiobooks

Oral History Audiobooks

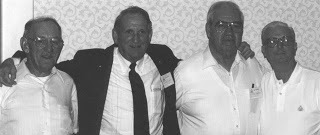

From left, Ed Spahr, Jim Gifford, Tony D'Arpino, Bob Rossi In 1991, at the annual reunion of the 712th Tank Battalion, I conducted an impromptu interview with Ed Spahr of Carlisle, Pa. I wasn't as familiar with the history of World War II as I am today, and the interview comprised mostly generic questions: Were you scared? How was the food? Were you wounded?

From left, Ed Spahr, Jim Gifford, Tony D'Arpino, Bob Rossi In 1991, at the annual reunion of the 712th Tank Battalion, I conducted an impromptu interview with Ed Spahr of Carlisle, Pa. I wasn't as familiar with the history of World War II as I am today, and the interview comprised mostly generic questions: Were you scared? How was the food? Were you wounded?That last question brought an interesting answer. It was during the Battle of the Bulge, his tank was knocked out, and his lieutenant was wounded. In fact, the bullet, most likely from a machine gun, was still sticking out of his head near one of his eyes. The lieutenant didn't know how badly he was injured/ When the crew abandoned tank and reached the relative safety of the other side of the tank, the lieutenant, Jim Gifford, handed Spahr a camera and said "Take my picture."

It was while he was holding the camera up to take the picture that he felt something like a bee sting on the fleshy inside part of his arm.

"I didn't even miss a day," he said.

A year later, at the 1992 reunion in Harrisburg, Pa., I got quite a surprise. I was in the hospitality room when Lieutenant James Gifford entered. Wide-eyed, I blurted, "You're Lieutenant Gifford!"

Spahr was at that same reunion, as was Tony D'Arpino, the tank driver that day, and Bob Rossi, the loader. The only missing member of the crew was Stanley Klapkowski, the gunner.

At that reunion, I sat down with the four crew members and they reconstructed the events of that day, and spoke of some of their experiences before and after the tank was knocked out. I had already interviewed Spahr and Rossi, and in the ensuing months I visited Gifford in the used-car lot he owned in Yonkers, N.Y., and D'Arpino at his home in Milton, Mass. Some time later I even visited Klapkowski in McKees Rocks, Pa., to get his version of the events.

All of those interviews make up my audiobook "Once Upon a Tank in the Battle of the Bulge," and a narrative version of the events comprise a chapter in my new book, "The Armored Fist," due out in April from the prestigious British publishing house Fonthill Media.

In the meantime, in conjunction with my Indiegogo campaign to help grow Oral History Audiobooks, here is an excerpt from that 1992 group conversation.

October, 1992, Harrisburg, Pa.:

James Gifford: I was a lieutenant at the time, a first lieutenant. When I left the service I was a captain in the Ninth Armored Group.

Bob Rossi: I was a loader in Lieutenant Gifford’s tank. I was a private first class. I got out of the service in January 1946.

Ed Spahr: I think I’d better be classed as a utility man with all of C Company because I served in every platoon. I think I spent more time in the front than a lot of other ones did, because if that platoon wasn’t there, I was with another one.

Tony Darpino: I was a driver, first tank, third platoon, and towards the end I was a tank commander for a very short period when the end was in sight. I was discharged in ’45.

Aaron Elson: Where did you come together as a unit?

Bob Rossi: Just prior to the Battle of the Bulge, Jim was brought in as our new tank commander.

Tony D’Arpino: He was our platoon leader.

Bob Rossi: We were in the No. 1 tank. We wound up in the town of Kirschnaumen in Belgium. I can recall so vividly how we wondered where Lieutenant Gifford was all day. We were in a hayloft, and he came up the ladder, it was a footladder, he said, “Come here, I want to show you something.” He had draped the tank in white sheets. They weren’t whitewashing the tanks at that time. There was snow all over the ground. So he scrounged these white sheets from all over and he draped our tank so we’d have camouflage.

That same night, he had gotten a package from home, and he had some canned chicken. He shared his package with all of us.

We were talking about home, and he said to us, “You know, I’d rather lose an arm or a leg than lose my eyesight.” He said, “There’s too much to see in this world.” And the next day when he got hit, he got hit in the eye.

It was a hairy situation because we had gone into a pocket to flush out the Germans, and as fate had it, our left track was knocked off.

Tony D’Arpino: Wasn’t that the time that we just took one section of the tanks, just us and the second tank? We were almost ready to eat supper when we had to go out.

Bob Rossi: We only had two tanks, us and [Sgt. Jim] Warren’s. There was concentrated machine gun fire. Lieutenant Gifford got hit in the right eye, the bullet lodged in his cheek. I thought he might jump out of the tank, and I yelled to him to keep down or they would blow his head off. He said, “I don’t want to jump out, I want Warren to come forward to help us.”

Then he said to me, “Rossi, how bad am I hit?”

And I lied, I said, “You don’t look bad, Lieutenant.” But he looked like somebody hit him in the face with a sledgehammer.

Tony D’Arpino: I remember something else about that, too. He was great for having a camera around your neck, right?

Bob Rossi: I’m gonna get to that. So he says to me, “Fire the smoke mortar.” And this is the joke. In my excitement, I forgot to knock the cap out of the top, and when I fired the first mortar it went like this [motioning straight up and down]. And then I fired some subsequent mortars to give a smokescreen.

As we were abandoning tank, Lieutenant Gifford was firing his .45 and pulling Spahr out by one of his arms. Spahr’s leg was locked.

Ed Spahr: I had a little blood coming out, something had hit me, I went along with him back to the aid station.

Bob Rossi: Ed was the assistant driver. His machine gun was firing by itself it was so hot. And I said, “Twist the belt, twist the belt,” so he could stop the bullets from feeding into the machine gun. And Klapkowski, who was our gunner, he and I were running in a zigzag, we could see the snow being kicked up around us. As we were running, a recon truck came toward us, and Lieutenant Gifford said, “Fire that .50 and protect these boys!”

And the guy yelled out, “It’s our last box!”

He says, “Fire it anyway, you sonofabitch!” And that’s when they started firing the .50 to give us cover.

As we got out of the line of fire, he handed his .45 to me, he says, “Hold this for me till I get back.”

And with that, he says, “Take my picture.”

I says, “Lieutenant, I can’t take your picture.”

Ed Spahr: I took it. That’s the only way I could have got hit, right here [on the inside part of the arm], when I was holding the camera up to take his picture. It felt like a bee sting.

Bob Rossi: And there he was, having his picture taken. He had gotten a Bronze Star that morning, he had the ribbon, his face was all puffed up, blood all over his combat jacket, he says, “Take my picture.”

Jim Gifford: I couldn’t see out of my right eye, but I didn’t know how bad it was. It’s a funny thing, I didn’t feel any pain when the bullet went in.

Tony D’Arpino: I can remember plain as day one thing about that night, that evening. We were about ready to eat our meal, whatever it was, and they said that there was a small pocket, it was holding the infantry down, they wanted the tanks to clean it out. You took two tanks. It was just supposed to be a small pocket. And it turned out to be a little more than that, I guess.

Jim Gifford: It was bad news.

Bob Rossi: After we were knocked out, Sergeant Warren’s tank came forward, and under Lieutenant Gifford’s orders, he set our tank on fire.

Tony D’Arpino: We had ruined the radio. We put a grenade in the gun barrel. We did everything we were supposed to do.

Bob Rossi: So the Germans couldn’t turn the gun around and fire on the town.

Jim Gifford: I had Warren shoot into the back of our tank because the Germans were stealing the tanks. They’d use them against us. The track was blown off so it was useless anyway.

Tony D’Arpino: But the gun was still good.

Jim Gifford: So we immobilized it by hitting it in the back.

Tony D’Arpino: We had the best working escape hatch of anybody in the platoon. I used to oil that thing up good, so that when you touched the lever it would really fall out. Sometimes that was the only way of escape. If you’re inside the tank and the hatches are down and the gun is traversed over your hatch, you can’t open it to get out, you have to go out the other way.

I can remember always telling Klapkowski, he was the gunner in the tanks that I was in most of the time, and I always told him, “You sonofabitch, if we ever get knocked out, make sure that gun’s in the center, because if I can’t get out because you’ve got the gun traversed over my hatch,” I says, “I’ll haunt you. I’ll come and pull the sheets off of your bed.”

Jim Gifford: I’m sure there’s a few guys that aren’t here today because of that gun being over their hatch.

Tony D’Arpino: That used to be my biggest worry.

Bob Rossi: We subsequently got a new tank after that. Sergeant Holmes became our acting platoon leader. When Lieutenant Gifford was wounded and we were knocked out, that was January 10, 1945, Berle, Belgium — Luxembourg.

Jim Gifford: Outside of Bastogne. Bastogne was right over there, we were heading for it. We had to go down a defile with a lot of woods and they were dug in there, but we didn’t know that.

Bob Rossi: We were committed to the Bulge already. When Lieutenant Gifford was evacuated, we waited maybe several weeks for a replacement tank, and that’s when we got this new tank, and Sergeant Holmes became our acting platoon leader. He was the platoon sergeant. And on February 8, 1945, we were knocked out again, at Habscheid, Germany. We were in a wooded area. They called us during the night.

Tony D’Arpino: In high ground, no?

Bob Rossi: In high ground. And it seemed like the Germans were just waiting there for us.

Tony D’Arpino: They had it all zeroed in. They had three lines of machine gun fire. Some just grazed the ground, some came waist-high.

Bob Rossi: When light came, it seemed like everything opened up at one time. They knew we were there, in the woods, and they had mortars, artillery, machine gun fire, and all of a sudden Sergeant Holmes collapsed in the turret, and I was yelling, “Holmes! Holmes! are you hit?” And Spahr says to me, “Sure he’s hit.” And with that we picked him up, and put him behind the gun. Shrapnel had gone through his steel helmet. He was hit in several places. The towel that was around his neck, a bath towel, was sopping wet with blood.

Later, after this happened, I noticed I had blood all over my left sleeve. And with that, I asked D’Arpino, “Give me the first aid kit.” And with that, he can’t open it. The darn thing was rusted shut. So with a chisel he opened up the first aid kit, and I bandaged Sergeant Holmes as best as I could, and as he’s laying on the floor he called up Sergeant Gibson, he says, “Gib, I’m hit, I’m getting out of here.” And Gibson called back, he says, “We’re all getting out of here.” And with that, Gibson started up the hill, and this is when we found out that the Germans had the hill zeroed in. As Gibson stopped, they fired two rounds in front of him and missed him. He took off. We came up the hill, and Bang, we got hit. The 88 went through our engine compartment and landed between [Jim] Sessions’ — he was the assistant driver — it landed between his legs.

Tony D’Arpino: He was a recruit.

Ed Spahr: First time up.

Bob Rossi: I think it was a day before or a day after his 18th or 19th birthday.

Tony D’Arpino: I was driving, and I knew there was another tank behind me to get out, so I tried pulling over to the right to give him room to get around me, and of course nothing was working. Sessions, the assistant driver, he was new, he grabbed the fire extinguisher, and I says, “Jump, you crazy bastard, jump!” Matter of fact, I didn’t even unplug the radio or nothing, I just got out.

Ed Spahr: He never did attempt to get out till I got ahold of him. I jumped back up on the tank and I grabbed him.

Bob Rossi: I neglected to say, one tank was already knocked out in the woods, their bogey wheels were knocked off, and we had taken two guys from that crew into our tank, so there were five of us in the turret when there should have been three. When we got hit, I was the last guy to get out. I was on my hands and knees waiting for the others to get out, and I no sooner got out of the turret than the ammo started to go.

Tony D’Arpino: It’s taking a while to tell this story, but it all happened within seconds, and when that thing hit and I saw that red projectile land beside Sessions’ foot — it came right alongside by the transmission, the transmission was between the driver and the assistant driver — it was laying right down by his left foot.

Jim Gifford: The projectile, gets red hot.

Ed Spahr: Cherry red.

Tony D’Arpino: I didn’t even bother unplugging my helmet radio. I just put my hand outside, tried to pry myself up, and that tank was just as hot as a stove.

Ed Spahr: When they hit us, it just felt like it drove the tank ten feet forward.

Bob Rossi: I automatically turned around when we were hit. I turned around to pull the extinguisher. We had an inside extinguisher. It didn’t do any good. The fire was so tremendous with all that gasoline.

And right after we got hit, just before I got out of the tank, that’s when the other tank, which was just about on our left rear, they got hit. But they weren’t as fortunate as us in the sense that [Grayson] LaMar, who was the driver, he was burned pretty bad, I can remember when he took that stocking mask off his face he took the skin right off his face. And Whiteheart, who is now dead, the type of tank they had, they had ammo stacked in back of the assistant driver, it shifted, hit him right in the back.

Van Landingham was the tank commander, part of his heel was torn off from the shrapnel.

Tony D’Arpino: I remember we got all the way down, we crawled all the way down that hill, got down to the bottom, and Van Landingham was missing, right? He’s still back up there. So I don’t know who the other guy was and myself, we grabbed a stretcher, we went back up — we crawled back up. They were shooting right over our heads. I thought that was my last day, out of all the — I had three tanks knocked out from under me, and out of all of them, I thought that was it. I had it.

So we crawled up there with a stretcher to get Van Landingham, right? We finally get to him and he’s moaning and groaning, I’m looking for blood, you know, I don’t see nothing. He’s got them combat boots on. I look, and he goes, “Ohhh, ohhh,” real sharp, right, now he must have been hit someplace, I don’t know where. I couldn’t see any blood. We’re trying to get him on that stretcher, and we’re trying to crawl on our hands and knees with the stretcher, get him down over the crest where they couldn’t see us. They had that place zeroed in. And we’d go a few feet, and then, “Shooom!” We’d drop the stretcher. The third time the stretcher hit the solid ground, Van Landingham, “Oooooh,” he would groan, anyway, God willing, we got him down to the bottom, and I don’t know who that man is today, I’ve thought about this a million times, but somebody saw me and whoever else had that stretcher, and it was an officer, not in our company, it was an officer that was down there, and he took our names, he thought we should get the Silver Star for what we had done. And then I was told later on that this man was called back to England, he had to be a witness in a court martial. I don’t know who the officer was. He wasn’t in our outfit.

Ed Spahr: He was a captain in the infantry up there. You remember, we all got up in that bunker?

Bob Rossi: We were going from pillbox to pillbox.

Ed Spahr: I’ll never forget that day. The snipers were, you raised up a little up a bit and Ping!

Tony D’Arpino: Every time we’d hear “ping” we’d drop the stretcher and Van Landingham would hit and he’d groan.

Bob Rossi: You know what was ironic? We were running from pillbox to pillbox to get out of the line of fire after this all happened. And the infantry was dug in in foxholes, they said, “Don’t run on the road, it’s mined. Don’t run in the gully, it’s mined.” And we finally got to this one pillbox, and I think it was a major or a lieutenant colonel, he wanted American wounded put outside because he complained that they were in the way of him conducting business. And we were PO’d at him. I was so mad at the time, I was only a kid, but I was so mad I felt like shooting the German prisoners who were there because they did this to us.

Ed Spahr: I remember that one infantry boy, this captain said to this guy, he pointed to him, he said, “Get up there and get that sonofabitch!” And that infantry boy was sitting there, he handed him his M-1, he said, “Here, you get him.”

Tony D’Arpino: If you remember, that night, it was dark when the infantry moved us up there.

Bob Rossi: It was raining.

Tony D’Arpino: We argued about it. You move the tanks at night, Jesus, they make too much noise. But the infantry officer said, “I’m giving you an order.”

Bob Rossi: So Holmes says to me, “Rossi, get out.” He handed me his tank commander’s watch with the luminous hands, he said, “Lead the tank.” Now I’m running in front of the tank in the rain, holding it up as I’m running so D’Arpino can see the watch in the dark. And when we got knocked out the next morning, I said to myself, “Thank God my clothes were soaking wet. I think that’s what saved me from getting burned to death in the tank.” All my clothes were soaking wet.

Ed Spahr: We lost four tanks that day.

Bob Rossi: Three. Three out of the four.

Ed Spahr: That’s right. Gibson’s was the only tank that got out.

Bob Rossi: Two tank destroyers were lost. And we lost about a company of infantry. I mean, we took a beating.

Tony D’Arpino: When daybreak came and I looked around, I said, “Hooooly shit.” You could see for miles. I mean, we were really exposed. They had three lanes of machine gun fire.

Bob Rossi: You remember later on we were kidding, it was bad, but later on we kidded, “That German gun crew must have all got the Iron Cross and a three-day pass.”

- - - Order "Once Upon a Tank in the Battle of the Bulge" on audio CDs from Amazon.com Bid on "Once Upon a Tank in the Battle of the Bulge at eBay (the price is a little higher but the shipping is free, and you can "make an offer" as well. Support Oral History Audiobooks

Published on March 09, 2013 19:54

February 25, 2013

A funny thing happened on my way to the bestseller list

I've had some interesting experiences promoting my books and audiobooks. A couple of years ago, at the Greenwood Lake air show, where I was displaying my audiobooks, to the right of my table was Dutch Van Kirk, the navigator on the Enola Gay; and to my left were two Tuskegee Airmen. I felt like a history sandwich.

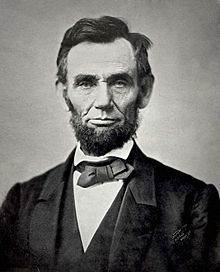

Then today, as my Amazon Kindle e-book edition of "A Mile in Their Shoes," which I made available for a two-day free download promotion (today, Feb. 25 and tomorrow, Feb. 26), was climbing the ranks of free Kindle books in the History category, I found my book at Number 38, just below, at No. 37, the Gettysburg Address. Pretty cool company, if you ask me.

Then something caught my eye. It was the stars signifying the reviews of the free edition of the Gettysburg Address; there was only an average of four and a half stars for 53 reviews. So I looked a little closer and discovered there were three one-star reviews. How could anybody trash the Gettysburg Address? Fortunately, only one of the one-star reviews was from some reprobate who probably has a Confederate flag hanging in his trailer. A more reasonable one follows, although still nobody should give the Gettysburg Address a rotten review, I mean, now I don't feel so bad about the handful of trashy reviews my own books have gotten, I'm in some pretty good company. Anyway, here's the review of the free edition of the address that I just mentioned:

6 of 9 people found the following review helpful

A review of Format, Not This Amazing Speech, January 19, 2012

A review of Format, Not This Amazing Speech, January 19, 2012 By Pam T "mom,wife,fur-mom"Amazon Verified Purchase(What's this?)

This review is from: Gettysburg Address (Kindle Edition) There are surely many who would like to own a copy of the Gettysburg Address. Read with an understanding of the times, one can't help but be moved by the eloquence of Lincoln's words, and the careful crafting that made this one short speech, so memorable.

What I am reviewing here is the Free "Vanilla Electronic Text" version of the speech which is available for Kindle. Though serviceable, I can't recommend it. For whatever reason, the publishers have chosen to replace commas with elipses. So that you get:

Quote:

Now we are engaged in a great civil war ... testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated ... can long endure.

REALLY?!?

Available elsewhere, for free.

Pam T~

mom/history lover

If you don't already have a copy of the Kindle edition of "A Mile in Their Shoes" and would like a free download today or tomorrow (Feb. 26), here's the link:

http://www.amazon.com/dp/B0045OUMTQ/worldwariioralhi

Update: I've moved past the Gettysburg Address and am currently at No. 18 in the History category of the free Kindle download list. At No. 17: True Irish Ghost Stories. Uh-oh ...

Published on February 25, 2013 10:54

February 23, 2013

More pictures from the archives

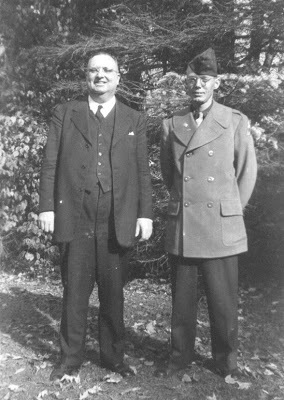

A Company, 712th Tank Battalion, officers at Amberg, Germany. Back row,

A Company, 712th Tank Battalion, officers at Amberg, Germany. Back row,from left: Morse Johnson, Sam MacFarland; front row, from left, Bob

Hagerty, Ellsworth Howard, Howard Olsen, Jule Braatz

I used this picture on the cover of the first edition of Tanks for the Memories. In the back row are Morse Johnson and Sam MacFarland, whom I mentioned in my previous post.

Bob Hagerty, on the left in the front, and Morse Johnson were both from Cincinnati, Hagerty from the Norwood section and Johnson from, I think it was called Far Hills. Both were sergeants in the horse cavalry, both received battlefield commissions, and both distinguished themselves in the battle for Oberwampach, as did Howard Olsen, third from the left in the front. When the 712th Tank Battalion was stationed as occupation troops in Amberg, Germany, after VE Day, Hagerty and Johnson often faced each other as opponents on a court-martial board; Johnson, a lawyer in civilian life, as the judge, and Hagerty as defense counsel.

Hagerty recalled one particular case involving an enlisted man named Everett Bays, who was court-martialed on three occasions. The first two were for minor offenses, stealing a jeep, things like that. But the third offense occurred while the battalion, already in Marseilles, was waiting to be shipped out for home. Bays got drunk and got into a fight with an officer from a different outfit and beat the officer pretty seriously.

Don Knapp, whom you may have seen interviewed on "Patton 360," remembered the fight for which Bays was court-martialed. At the battalion's 1993 reunion, Knapp recalled a conversation he had with Tony D'Arpino, who also was interviewed in Patton 360.

"D'Arpino said, 'You remember that night when we were going home, we were in this area," and he says, 'it was all muddy.'

"And I says, 'Yeah, and they had strips of wood to walk on.'

"He said, 'And Bays got drunk and he was an ex-prizefighter and he was slapping people around.'

"I said, 'You don't remember, Tony, but I was charge of quarters that night.' By that time I was a staff sergeant.

"And he said, 'No I don't.'

I said, 'Well, I picked up a log out of that walkway,' because he had hit one guy real hard and I walked in he was slapping somebody. And I said, 'Cut it out, Bays.' You know, appealing to his better nature.

"And he said, 'You shut your mouth or you're gonna get it, too.'

"And I've got a .45, but he had one too.

"I said, "You put that gun down.'

"And he said, 'What the hell are you gonna do about it?'

"I said, 'Why don't you put the gun down?' And I says, 'We'll settle it.' And I'm holding the thing in back of me, and I thought to myself, if he comes up close I'm gonna nail him, because I couldn't take him. That guy was a prizefighter. I was not about to go up against him without something. I wouldn't shoot him, but I had this big birch log in my hand in back of me and he didn't see it because he was half-bombed and I thought, I've been around drunks before and if he's up close he's gonna get you but he was kind of staggering, I thought, 'I'm gonna stay back and I'm gonna let him have it alongside the head.' I think somebody, they all jumped on him when I was talking to him. Bays. He was something else."

Luckily for Bays, the officer he injured shipped out for home the next morning, and all the court-martial board could do was take his deposition. Bays still was court-martialed, but got off with a slap on the wrist. As Hagerty recalled, the battalion commander, Col. Vladimir Kedrovsky, was so incensed over the outcome that he fired the whole court-martial board. The battalion, Bays included, shipped out the next day.

Ellsworth Howard

Ellsworth HowardEllsworth Howard, second from the left in the group picture, was the A Company executive officer until Clifford Merrill was wounded on July 13, and then he took over as company commander until August 18, 1944, when he was wounded at the Falaise Gap. He returned later in the war.

I never did a formal interview with Ellsworth, but did do a couple of brief interviews during battalion reunions. Following is an excerpt from the first edition of "Tanks for the Memories":

Ellsworth Howard: "You could only get a replacement tank if you lost one in battle, and the replacements were slow in coming through. We had a void of tanks for a long time.

So I started battle losing them on paper. And then the durn war ended before my tanks balanced out. I had four or five too many, and we had to turn them in at Nuremburg.

"We went to an ordnance place down there and turned the tanks in, and they wouldn’t take but just the number listed in the table of operations.

"I said, 'What am I gonna do with the rest of them?'

"'That’s not our problem.'

"So I found a field down there right close by, and parked those tanks, got out and left. A week or so later a guy named Marshall House called, and he said, 'Are you by any chance from Louisville?'

"I said, 'Why, I sure am.'

"And he said, 'Well, this is Marshall House.'

"I said, 'Why, I remember you, Marshall.' And we talked about old times.

"And then he said, 'What about these tanks down here?'

"I said, 'I can’t hear you. It must be a bad connection.'"

Howard Olsen

Howard Olsen  Jule Braatz

Jule BraatzHere are some more photos:

Jim Cary, left, and Joe Fetsch. Cary was the original

Jim Cary, left, and Joe Fetsch. Cary was the originalC Company commander, was wounded on July 3, 1944,

took command of B Company when he returned,

and was wounded on Jan. 9, 1945 in the Battle of the

Bulge. Fetsch drove a gasoline truck and was wounded

on April 3, 1945, in the explosion at Heimboldshausen.

Colonel George B. Randolph

Colonel George B. Randolph Colonel Randolph's body when he was killed during

Colonel Randolph's body when he was killed duringthe Battle of the Bulge. This picture appeared

in the Saturday Evening post, although he was

identified only as a colonel.

A platoon of A Company tanks in Bavigne, Luxembourg during the Battle of the

A platoon of A Company tanks in Bavigne, Luxembourg during the Battle of theBulge. The driver of the lead tank is Dess Tibbitts; the tank commander, on the left

side in the lead tank, is Lt. Wallace Lippincott, Jr., who would be killed a few days later.

The commander of the second tank is Sam MacFarland. The commander of the fourth tank is

Hank Schneider, who would be killed by a sniper in March of 1945 on the day he received

his battlefield commission.

Dess Tibbitts in 1988

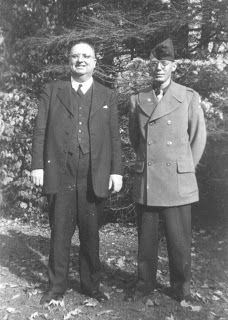

Dess Tibbitts in 1988 The Rev. Edmund Randolph Laine and Ed Forrest

The Rev. Edmund Randolph Laine and Ed Forrest

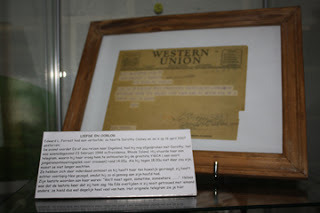

The entry in Rev. Laine's diary for the day Ed was killed. The death is noted

The entry in Rev. Laine's diary for the day Ed was killed. The death is notedas a footnote, because it would be 13 days before the telegram arrived.

(More pictures to come)

Published on February 23, 2013 17:07

February 20, 2013

Some pictures from the archives

Lisa Keithley and Dale Albee In 1999, Lisa Keithley of Vancouver, Washington, contacted me via email after finding a story by her great-grandfather, Walter Galbraith, on my web site, tankbooks.com. She said that after her great-grandmother passed away, she inherited Walter's memorabilia from World War II, including his uniform, and she was doing a school project on his service. I immediately remembered Walter Galbraith. He was one of the most upbeat, humorous veterans I'd interviewed, even though he was in remission from cancer and would pass away only a year or two after the interview. I used a couple of his stories in my first book, "Tanks for the Memories." Like the story about the time he went to check on "Little Joe." Little Joe was the generator in the tank, which was parked near the side of a building during what likely was the Battle of the Bulge. It was early in the morning and the rest of his crew was inside the building. A 75-millimeter round was in the chamber of the tank's cannon, and as Walter climbed into the tank, his foot accidentally hit the solenoid that fired the gun. There was an explosion in the ground in front of the tank, and Walter immediately feared that he might have killed somebody. As he climbed out of the tank prepared to "face the music," as he said, the sergeant came running out of the building, nobody had been injured, and the sergeant muttered an expletive and said something like "I drove over that spot three times last night and didn't go over that mine!" Relieved, Walter then heard Andy Schiffler, the driver of another tank in his platoon, begin to say "That was no mine ..." so Walter grabbed Andy and told him to shut up. I also remembered Dale Albee, who was Galbreath's tank commander, telling me how he teared up when he heard that Walter had died. Galbreath was Albee's gunner during a particularly harrowing incident during the Battle of the Bulge when the platoon stopped a counterattack in the middle of the night, as well as through many other incidents. Lisa mentioned in her email that she lived in Vancouver, Washington. I had traveled to Prospect, Oregon, to interview Albee, and I thought, heck, northern Washington, southern Oregon, heck, they're practically neighbors, how far could that be? (279 miles, thank you, Mapquest). So I asked Lisa if she'd like to meet her great-grandfather's lieutenant. Dale said he had a daughter he was going to visit in Vancouver over the holidays that year, so he visited with Lisa, resulting in the above meeting, which was covered by the Vancouver Sun.

Lisa Keithley and Dale Albee In 1999, Lisa Keithley of Vancouver, Washington, contacted me via email after finding a story by her great-grandfather, Walter Galbraith, on my web site, tankbooks.com. She said that after her great-grandmother passed away, she inherited Walter's memorabilia from World War II, including his uniform, and she was doing a school project on his service. I immediately remembered Walter Galbraith. He was one of the most upbeat, humorous veterans I'd interviewed, even though he was in remission from cancer and would pass away only a year or two after the interview. I used a couple of his stories in my first book, "Tanks for the Memories." Like the story about the time he went to check on "Little Joe." Little Joe was the generator in the tank, which was parked near the side of a building during what likely was the Battle of the Bulge. It was early in the morning and the rest of his crew was inside the building. A 75-millimeter round was in the chamber of the tank's cannon, and as Walter climbed into the tank, his foot accidentally hit the solenoid that fired the gun. There was an explosion in the ground in front of the tank, and Walter immediately feared that he might have killed somebody. As he climbed out of the tank prepared to "face the music," as he said, the sergeant came running out of the building, nobody had been injured, and the sergeant muttered an expletive and said something like "I drove over that spot three times last night and didn't go over that mine!" Relieved, Walter then heard Andy Schiffler, the driver of another tank in his platoon, begin to say "That was no mine ..." so Walter grabbed Andy and told him to shut up. I also remembered Dale Albee, who was Galbreath's tank commander, telling me how he teared up when he heard that Walter had died. Galbreath was Albee's gunner during a particularly harrowing incident during the Battle of the Bulge when the platoon stopped a counterattack in the middle of the night, as well as through many other incidents. Lisa mentioned in her email that she lived in Vancouver, Washington. I had traveled to Prospect, Oregon, to interview Albee, and I thought, heck, northern Washington, southern Oregon, heck, they're practically neighbors, how far could that be? (279 miles, thank you, Mapquest). So I asked Lisa if she'd like to meet her great-grandfather's lieutenant. Dale said he had a daughter he was going to visit in Vancouver over the holidays that year, so he visited with Lisa, resulting in the above meeting, which was covered by the Vancouver Sun. A Company officers, 712th Tank Battalion, Amberg, Germany, 1945 I used this picture on the cover of the first edition of "Tanks for the Memories." It shows six officers from A Company -- five lieutenants and a captain -- in Amberg, Germany, where the 712th Tank Battalion was stationed after the war in Europe was over.

A Company officers, 712th Tank Battalion, Amberg, Germany, 1945 I used this picture on the cover of the first edition of "Tanks for the Memories." It shows six officers from A Company -- five lieutenants and a captain -- in Amberg, Germany, where the 712th Tank Battalion was stationed after the war in Europe was over.Because my father was in A Company, I took a special interest in the veterans of A Company, and although none of the men in the photo are alive today, I was able to meet all six of them, interview four of them at length, and one of them briefly a couple of times during reunions.

The two men standing are Morse Johnson, on the left, and Sam MacFarland. I wrote an earlier blog entry about Johnson, although I failed to mention that there are only two statues that I know of dedicated to veterans of the 712th. One is of Tullio Micaloni, a sergeant who was killed at Seves Island in Normandy and who is one of four soldiers on the 90th Infantry Division monument in Perier, France. The other is Morse Johnson, and it stands near the Playhouse in the Park in Cincinnati's Mount Adams district. Unlike most statues dedicated to heroes, Johnson isn't riding a horse or sticking his head out of a tank, in fact you likely wouldn't know it was him unless you read the plaque, as the statue is an abstract figure of a human form. After the war, Johnson was a patron of the arts, and was a founder of the Playhouse in the Park, which even today has a Morse Johnson Society for donors.

The Morse Johnson Memorial Johnson entered the horse cavalry and became a sergeant, later receiving a battlefield commission with the 712th. His platoon withstood nine counterattacks at Oberwampach during the Battle of the Bulge. When I interviewed Morse in 1992 during a trip to Cincinnati, he apparently was in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease, which would claim his life a few years later. Standing to Morse's right is Sam MacFarland, who introduced me to the 712th Tank Battalion Association, and helped me find three veterans who remembered my dad (who was wounded twice but survived the war, and passed away in 1980). I would love to have interviewed Sam, but he died of cancer before I attended another reunion. Shortly before passing away, Sam wrote in a letter to Ray Griffin, then the battalion association president, that "Time is succeeding where Adolf Hitler failed." I heard many stories about Sam, including one where he learned while in combat that his wife, Harriet, had given birth to a daughter. He was a sergeant at the time, and conferred with the members of his crew as to what she should be named. They came up with Lucky. Sam was one of 14 members of the battalion to receive battlefield commissions. If a picture is worth a thousand words, I'd better post this before the rest of the day flies by, and I'll get to the four men sitting in the front row, from left, Bob Hagerty, Ellsworth Howard, Howard Olsen and Jule Braatz, in my next post.

The Morse Johnson Memorial Johnson entered the horse cavalry and became a sergeant, later receiving a battlefield commission with the 712th. His platoon withstood nine counterattacks at Oberwampach during the Battle of the Bulge. When I interviewed Morse in 1992 during a trip to Cincinnati, he apparently was in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease, which would claim his life a few years later. Standing to Morse's right is Sam MacFarland, who introduced me to the 712th Tank Battalion Association, and helped me find three veterans who remembered my dad (who was wounded twice but survived the war, and passed away in 1980). I would love to have interviewed Sam, but he died of cancer before I attended another reunion. Shortly before passing away, Sam wrote in a letter to Ray Griffin, then the battalion association president, that "Time is succeeding where Adolf Hitler failed." I heard many stories about Sam, including one where he learned while in combat that his wife, Harriet, had given birth to a daughter. He was a sergeant at the time, and conferred with the members of his crew as to what she should be named. They came up with Lucky. Sam was one of 14 members of the battalion to receive battlefield commissions. If a picture is worth a thousand words, I'd better post this before the rest of the day flies by, and I'll get to the four men sitting in the front row, from left, Bob Hagerty, Ellsworth Howard, Howard Olsen and Jule Braatz, in my next post.

Published on February 20, 2013 06:34

February 16, 2013

The Accidental Conspiracy Theorist

A scene from The Twilight Zone, "The Purple Testament" I should have known better than to reference The Twilight Zone in the introduction to my new two-CD audiobook "Premonitions, Visions, Nightmares and Other Unexplained Circumstances." Of course I remembered the episode about a World War II soldier who can look into another soldier's face and tell if that soldier is going to be killed, what could be wrong with mentioning that? YouTube, that's what.

A scene from The Twilight Zone, "The Purple Testament" I should have known better than to reference The Twilight Zone in the introduction to my new two-CD audiobook "Premonitions, Visions, Nightmares and Other Unexplained Circumstances." Of course I remembered the episode about a World War II soldier who can look into another soldier's face and tell if that soldier is going to be killed, what could be wrong with mentioning that? YouTube, that's what.So I go to YouTube and do my due diligence, typing Twilight Zone and World War II into their search thingie and before you can say Clem Kadiddlehopper I learned not only that I was looking for Episode 19 but that it was titled The Purple Testament.

Naturally, I thought I'd watch the few minutes of it that were available on YouTube. The first segment I watched was either in Spanish or Portuguese, it was posted by a Brazilian so it was probably the latter, and even though I didn't understand a word, the music was sufficiently creepy to get the show's message across. Then I found pretty much the same footage in English and watched that.

But was I finished? Nooooo. There was a picture from Episode 19 with the title "Was Kennedy's Death Predicted in Hollywood?" Click. The video begins with a line of text saying that we all know that Sept. 11 was predicted, superimposed over a scene of Homer Simpson looking at a tourist flier that says New York and a big dollar sign followed by the number 9, and just to the right of the number 9 are the twin towers so that it looks like 9 11. What? You have an argument with that? How about a screen shot from a 1993 Mario Bros. game showing smoke rising from the Twin Towers?

And then the question: Did Hollywood predict the death of John F. Kennedy. The soldier who could see the strange light in the faces of those about to die was named Lieutenant Fitzgerald. John F. Kennedy was a lieutenant in World War II and his middle name was Fitzgerald. Of course the conspiracy theorist who uncovered this misspelled his name as Frizgerald, but we all know that JFK was not John Frizgerald Kennedy, why let a typographical error get in the way of a good conspiracy?

Needless to say, there are eight minutes and 48 seconds of items like "This soldier's name was Freeman ... Orville Freeman nominated Kennedy for President."

Oh. Did I mention that the video begins with a photo of a sign painted on a highway overpass that says: "Caution 9' 11" "

Which brings me to my newest double audio CD, which will be available shortly in my eBay store. Here are some excerpts:

Dan Diel Lou Putnoky Patsy Giacchi

Published on February 16, 2013 22:17

February 2, 2013

Two (or maybe three) Degrees of Separation