Aaron Elson's Blog, page 18

June 28, 2013

Extract Digit

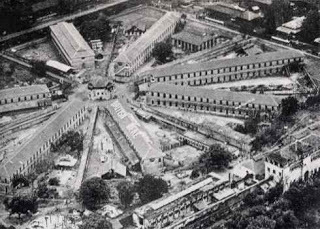

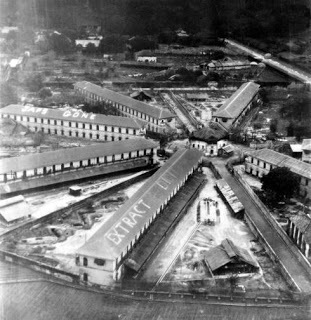

Is there an etymologist in the house? The above picture appears to have been photoshopped, but only to highlight the message on the roof of one of the cellblocks in the Rangoon Central Jail complex.

The complex housed more than 1,000 British, American and Indian prisoners of the Japanese. I interviewed one of those former prisoners, Karnig Thomasian of River Edge, N.J., in the late 1990s. Karnig was a waist gunner on a B-29 which was badly damaged over Thailand when a 1,000-pound bomb and a 500-pound bomb, with uneven trajectories, exploded beneath his plane. Over the next few months he was subjected to starvation and regular beatings by his Japanese captors. And then on May 1, 1945, as a battle was raging in the city, the prisoners awoke to discover that the Japanese guards had abandoned the complex overnight.

The liberated inmates remained inside the compound and, fearful of being bombed by their own countrymen, painted messages on two of the cellblock roofs. One of them said "Japs Gone," while the other said "British Here."

"British Here" is barely visible in the lower center cellblock. The words "Japs Gone" would be two cellblocks to the left, just out of the picture. A Royal Air Force Mosquito nevertheless bombed the outer perimiter of the complex, according to a written account by Donald Lomas, one of the British prisoners. The British then climbed to the roof of another cellblock and painted "Extract Digit," a story told by Karnig and confirmed in Lomas' written account.

"British Here" is barely visible in the lower center cellblock. The words "Japs Gone" would be two cellblocks to the left, just out of the picture. A Royal Air Force Mosquito nevertheless bombed the outer perimiter of the complex, according to a written account by Donald Lomas, one of the British prisoners. The British then climbed to the roof of another cellblock and painted "Extract Digit," a story told by Karnig and confirmed in Lomas' written account.

The idea being that the pilot who bombed the complex might have thought the words "British here" was a ruse by the Japanese to prevent them from being bombed, much like American GIs would use questions like "What is the capital of North Dakota?" to challenge unknown soldiers, knowing that no German in an American uniform was likely to know the capital of North Dakota. Come to think of it, I don't know what the capital of North Dakota is. Ach du liebe! Ich bin ein Berliner! (On the recent anniversary of that famous statement by President John F. Kennedy, numerous wags pointed out that a "Berliner" was the German word for a jelly donut, and that President Kennedy, at the site of the former Berlin wall, was announcing, in effect, "I am a jelly donut." But I digress.) The phrase worked, and an RAF bomber passing overhead tipped its wings to a round of cheers and flew to a nearby airfield. The good news is that the bomber landed on the only runway that wasn't mined by the Japanese. The bad news is that its wheels got caught in a bomb crater and the plane was severely damaged. So the pilot and crew walked to the prison compound and discovered it to have been freed. Supplies were then dropped in by parachute. Following is an excerpt from my interview with Karnig Thomasian's in which he discusses the compound's liberation: Karnig Thomasian:We were losing people from lack of food, lack of nourishment. There was a shack, a brick building on the corner of our compound, and it was the warehouse, small as it was, of food. Like eggs. It had a door in the brick wall, and the guys had slowly taken the cement from the bricks to the point where the whole housing of the lock assembly came out with the door and the door just opened. But you can’t go in and just ransack the place. You’d do it one time and that’s it. So whenever somebody was really ill to the point that they need the nourishment of an egg, they’d go in and get one or two eggs, period, and that’s it. And then only by the direction of the commandant of our group, whoever was the highest officer there. And this is, we’ll get to this, we haven’t gotten to this stage yet where they were dropping food containers. They bombed us by mistake. We said, "Japs gone." The British fighter planes thought they were joking so they bombed us. They missed and hit one of the outer walls. So the British prisoners got up and wrote this, "Extract Digit."

The idea being that the pilot who bombed the complex might have thought the words "British here" was a ruse by the Japanese to prevent them from being bombed, much like American GIs would use questions like "What is the capital of North Dakota?" to challenge unknown soldiers, knowing that no German in an American uniform was likely to know the capital of North Dakota. Come to think of it, I don't know what the capital of North Dakota is. Ach du liebe! Ich bin ein Berliner! (On the recent anniversary of that famous statement by President John F. Kennedy, numerous wags pointed out that a "Berliner" was the German word for a jelly donut, and that President Kennedy, at the site of the former Berlin wall, was announcing, in effect, "I am a jelly donut." But I digress.) The phrase worked, and an RAF bomber passing overhead tipped its wings to a round of cheers and flew to a nearby airfield. The good news is that the bomber landed on the only runway that wasn't mined by the Japanese. The bad news is that its wheels got caught in a bomb crater and the plane was severely damaged. So the pilot and crew walked to the prison compound and discovered it to have been freed. Supplies were then dropped in by parachute. Following is an excerpt from my interview with Karnig Thomasian's in which he discusses the compound's liberation: Karnig Thomasian:We were losing people from lack of food, lack of nourishment. There was a shack, a brick building on the corner of our compound, and it was the warehouse, small as it was, of food. Like eggs. It had a door in the brick wall, and the guys had slowly taken the cement from the bricks to the point where the whole housing of the lock assembly came out with the door and the door just opened. But you can’t go in and just ransack the place. You’d do it one time and that’s it. So whenever somebody was really ill to the point that they need the nourishment of an egg, they’d go in and get one or two eggs, period, and that’s it. And then only by the direction of the commandant of our group, whoever was the highest officer there. And this is, we’ll get to this, we haven’t gotten to this stage yet where they were dropping food containers. They bombed us by mistake. We said, "Japs gone." The British fighter planes thought they were joking so they bombed us. They missed and hit one of the outer walls. So the British prisoners got up and wrote this, "Extract Digit."Aaron Elson:And what does that mean?

Karnig Thomasian:In British terms? "Take the finger out of your ass." So right away they came back and they waved their wings. Then they came back and they dropped food containers. I mean, would you believe? It’s just wild. What brilliance to come up with that. "No, they’re really gone!" No, "Extract Digit."

Aaron Elson:How much did you weigh when you were liberated?

Karnig Thomasian:I forget, 115, 120, something like that. Not much.

Aaron Elson:And what did you weigh when you were captured?

Karnig Thomasian:I imagine then I was around 165.

Aaron Elson:Was there any contact with the Red Cross when you were a prisoner, or was that only in Europe?

Karnig Thomasian:No contact whatsoever. We had no contact with anybody.

Aaron Elson:Had your parents been notified that you were a prisoner?

Karnig Thomasian:That’s another story. Mom wrote a diary, in one of these little school composition books. I still have it. It’s one of those notebooks the kids used to have that looks like a cow’s skin, only smaller. So she wrote, "Oh, I don’t know where you are but I know you’re going to be all right, and we miss you." She’d write to me every now and then. Not every day. On the day that we were – I call it liberated because that’s when the Ghurkas came in, the Japs had gone and the Ghurkas came in and this one newspaperman, an American newspaperman, he was the first one in there. He was fabulous. On that day, she said, "Karnig, I know you’re alive." It’s phenomenal. And the date’s there and everything. I could not believe it when I read it, when I got back, she showed it to me some time later.

Aaron Elson:What day was it you were liberated?

Karnig Thomasian:May something. Let’s see if I have it here. Six Ghurkas. May 3rd. (Reading) "I woke up at the crack of dawn, helped prepare the breakfast for our compound. We still had some condiments from the food containers that were parachuted by the British. We all started to gather what little we had so that when the time came to leave, we’d be ready. Later that morning an American officer entered our prison with his aide." That was General Stroudemeyer. I’ve got a picture with him.

Aaron Elson:How did you readjust after being a prisoner?

Karnig Thomasian:Well, I was in the hospital for a month in Calcutta, and they just fed us and they took care of our sores. I mean, these sores, the jungle sores that I got on my ankles, that’s why I didn’t go on the march. I had a choice, am I well enough to go on the march? They said, "Those that are able to walk, we take." Then you’d wear their fatigues, the Japanese fatigue uniforms.

Aaron Elson:What was the march?

Karnig Thomasian:The Japanese contingents were leaving and they used them as hostages, in their minds. Later on what happened was they left them, they just ran for their lives. The guys were lucky, but along the way they killed some people because they slacked back and that’s what I was afraid of. I said, gee whiz, if I can’t walk, what’s gonna happen? So I flipped a coin to myself and I said, I’ll stay back and I’ll be able to help the guys that are really bad off here, and hopefully they’re not gonna kill us all. Why would they? So that’s what we did.

Aaron Elson:Tell me more about the sores.

Karnig Thomasian:I got jungle sores. Because my GI shoes had heels, and there were corners, and at night I’d itch, and pretty soon I opened the wound and sure enough, they became deep sores. And the only way I could clean it – there was no medication – was to boil water and tear a piece of my suntans, which I didn’t wear, I wore a little loincloth, and just laboriously clean it out. Each time. Oh, Jesus.

Aaron Elson:That must have been painful.

Karnig Thomasian:Oh, yes. But you had to do it. And then you’d walk around with a flap on the top because flies were all over the place, so you don’t want them to hone in on it.

Aaron Elson:And what about bruises from the beatings?

Karnig Thomasian:Well, they heal.

Aaron Elson:Did you ever get any broken bones?

Karnig Thomasian:No, thank God.

Aaron Elson:And what about the guys who were in worse shape than you were?

Karnig Thomasian:Well, they had problems. There’s this Montgomery, who I told you about. I have a whole story on him, it’s all in there, where they had to, his hand was hanging by a thread, you see, and they had to cut it off. They severed that. But then it started to get gangrene, so they had to cut it below the elbow. Well, now this doctor, Dr. McKenzie was his name, a British doctor, he performed the operation. First the Japanese tried, and they gave him a shot of something which was the wrong thing and it drove him nuts, and they stopped. And the Japanese were just brutal, they were ridiculing him, "Ah, you, shut up!" Not shut up, whatever they said. So finally the British commandant appealed to the commandant of the Japanese, Look, let this man do the operation. He knows how to do it. Still, they had no anaesthetic, no nothing. Boy, we heard his screams, I hear them today. I tell you, it is absolutely profound. He passed out. How he went through it I’ll never know. A nice young man. So Dr. McKenzie did the operation, and by God, it held. And don’t ask me how he didn’t get infected. We don’t know. You know, we need the stories, they’re so unexplainable. In that humid climate, there were no bandages, there was cloth. Oh, jeez, I don’t even like to think about it. And Parmalee was another one. He had that shattered [bicep], and they had to squeeze the pus out all the time, my friend did that.

So then we got out of Rangoon. We went to a hospital ship, and they deloused us and we threw all our clothes out the hatch. In the shower room there was a hatch, we threw the clothes out into the Indian Ocean. But I kept my leather jacket. And I kept the big gun, the rifle that I had been able to bring on board. Aaron Elson:How did you get a rifle?

Karnig Thomasian:When the Japs had left, finally, we took over the place. My New Zealand friend and I were sitting on the steps of the compound, and I was smoking tea leaves; I never smoked in my life, but I started there. So we’re looking out over the city and we see Boom! Boom! Boom! They’re blasting things. And it’s late at night, and we’re saying, "Hey, I haven’t seen a guard come around, have you?"

"No." We walked around, and we went into this hut again, took the brick out, walked to the front and looked, and we could see from there that the main gates were open. When I say gates, they were these big teakwood doors, ten feet high. They were open, and I didn’t see any movement. We stayed there about ten minutes. So he said, "Something’s going on, let’s go back." We talked to the wing commander, and he said, "All right. Don’t tell anybody because it’ll be a riot here." So we hopped over the wall – it’s only about eight feet, you hike a guy up and he gets up and over. We hopped over and went down there. Now we’re taking a risk. Now we’re in dead man’s land, about seven of us. And some of the guys went to the gate and they saw a note. I have a copy of the note. "We meet you on future battlefields, and now you are free to go." Bullshit. Now we’re afraid to go further, maybe it’s boobytrapped. So, back in the fields there are cows. The British guys went and got a couple of cows and they made them walk around. The cows meander, they don’t go straight, so oh boy, they’re screening it real good. I expected one of them to blow up, but no. They went out the front door and we ran for the front door and closed it. This was late at night. And we put the planks down and blocked it, because we had all the piles of rice and stuff and cows, and Rangoon was starving. Then we went and ransacked the Japanese area. And then we gathered the guns and ammunition, and we found a few hand grenades, and I found a carved ivory cigarette holder that I kept. So now we had to negotiate with the townspeople, and finally we found one guy who was going to help us round up the people who owned boats and gather all the boats so that when the army landed on the other side, they’d have the little boats and could bring them over to this side. So myself and Dow, that fellow Dow, and Cliff Emony and this Burmese fellow, we went over to the other side of the river and went to the huts; they offered us food but we wouldn’t dare take any, or water – you’d get sick, you’d die. We’re not used to their food. It’s not clean, anyway. It’s just terrible. They’re used to it. Their bodies assimilate it. And so we got all our negotiations done, and we had our rifles as if, what was gonna happen I don’t know, and then we came back. That’s when this newspaper man came and the Ghurkas landed the next day. Aaron Elson:Those Ghurkas must have been awesome.

Karnig Thomasian:Oh, they are. They’re little fellows, but I’m glad they’re on our side. Boy, I’ll tell you what they did. We were ready to go, and this fellow looked so beautiful, he was 6-foot-4, broad, rosy – apples for cheeks – and when we looked and saw our pale faces, we realized really how sick we were because before that we didn’t have anything to relate to. The Japanese have a different coloring altogether, so we thought everything was all right.

We helped all the guys; there were some we had to carry out of their hospital-like situation, and we brought them in to the tender that was there. Oh, I was telling you about this Ghurka. We gathered around him like Gulliver, you know, with the little people, it was a scene. Oh, if they do a film I could just direct this scene, it was so precious. I remember every moment of it. Then the next morning we gather our things, we’re going to have a last breakfast, and then pretty soon it’s time to go to the tender that takes us out to the hospital ship, because the hospital ship can’t get in there. We’re ready to leave, and then we see these Ghurkas, they’re waving, waving, and then they’ve got one Japanese on a rope with his head bandaged, and there’s three or four of the Ghurkas holding a box between them, and the other Ghurkas are following up. And they’re all running like crazy trying to meet us. They brought us a gift. What was this gift? This was this Japanese soldier which they threw in the brig – they have a brig there – he was a young fellow – and they opened the box. It was full of ears. I was mortified. If you can believe it, I felt sorry for this guy, because he had never done anything to me. Oh, my God, how could they do this? It’s terrible. This is a present? I don’t know what they did with it. I couldn’t look at it anymore. Then they got us out to the ship. They deloused us. Aaron Elson:You hadn’t mentioned the lice before.

Karnig Thomasian:Oh, lice, yeah, in the seams of our loincloths and everything, because we didn’t wear clothes, you didn’t have to wear clothes, but they get into the seams, so you’d have to get them out. The best way is to put the clothing out in the sun, and you see them starting to crawl out, and then you squash them. That’s the way it is.

Aaron Elson:And they had no delousing facility in the camp?

Karnig Thomasian:No, they didn’t have anything. All that stuff, they didn’t have delousing, they didn’t have Mercurochrome. They didn’t have nothing.

Aaron Elson:Were there rats or mice?

Karnig Thomasian:There were big cockroaches. Big ones. You went "POW!" But I wouldn’t do it in my bare feet – I was always barefooted, so I said, "Does someone have a shoe?" Oh, God. Oh, jeez, I tell you, I sometimes wonder how I…

So we get there, and then we’re in the ship. And now it’s time to get off the ship. And they tell us, "No arms. Leave your firearms or anything else that you’ve gotten, swords and everything. …" So I dismantled the gun and put it in my blanket. We each got a blanket issued to us. So now it was a shorter thing. I managed to smuggle it off the ship that way. Then we got to the hospital, and they started feeding us. The first thing they did was clean our wounds. They put that sulfa powder in, and I tell you, in no time – almost in minutes, but it wasn’t, it was a couple of days, but the sores filled up and started to heal, it was a miracle. That’s a miracle drug as far as I was concerned. It healed it so fast. And that’s all we needed. From that to suffering like that. Oh, there was a general who visited us in the camp along with the American newsman. I never got his name. And he said, "We will wire news ahead that you people have been freed." Then when we got to the hospital, we met General Stroudemeyer, and I’ve got a picture with him. With my beard. I’m the only one that had a beard, I shaved everybody else. The wing commander wanted me to shave. He said, "Why don’t you shave?" I said, "No." He said, "Do you want to be the only one with a beard?" Oh, in the hospital, so they had bowls of pills. You just grabbed pills and ate them by the handful. It’s unreal. And ice cream. Aaron Elson:What were the pills?

Karnig Thomasian:All kinds of vitamin things, who knows? I have no idea. All colors. Rainbow. But there was a bowl, on every table. I don’t know, it sounds ridiculous, you’d take one of this, and one of that. I guess we were lacking in so many things they said it can’t hurt.

Then I went over to the Chinese compound, and I met this fellow. I can’t remember his name now, but he was the one that doled out the rice when we were in solitary. He had a black skullcap, a white, flowing shirt, short black pants, and sandals. That’s how he came around. And he’d always look to see if he could give us a little more, if the Jap wasn’t over his shoulder; we couldn’t converse. But I always remembered him. So I went over to where the Chinese were and I found him, and I said, "Does anybody speak English?" One of the fellows could speak a little English. I said, "Tell him that I want to thank him for his kindness." He told him, and then I said, "He made life more bearable for us, and he was such a nice man." Then the guy who was interpreting said, "Could he give you his father’s address, and you write to him, tell him that you saw his son and he’s all right?" I said, "Oh, sure." He gave me the address. And then the Chinese fellow got a coin, and he broke the coin. And he said, "When we meet again, we will match the coins." So I wrote to his parents. His father had a pharmacy in some town in China. Along comes a letter back, all in Chinese. I was going to art school then; this is when I was back in the States. There was a letter to me, and a letter to his son. So I showed it to my friend – I had a friend in school, the Art Students League in New York, a Chinese guy – and I said, "Do you know how to read Chinese?" "Oh, yeah." "I wonder if you could please translate these letters, so I could understand what it is and send it to his son?" He said, "Sure." So he gave me the translation in the next couple of days. He said, "I didn’t translate his son’s letter because that’s private." I said, "That’s okay." The father said he hadn’t seen his son all those years. That was the first time he’d heard anything about him. And it was so nice of me to write, and his mother is happy to hear that he’s okay. And he said, "Do you think you could send him a letter?" I don’t remember what he wanted to say. He wanted to get in touch with him, basically, that’s what it was. So I said, All right. Let me find out. I called up the 142nd General Hospital, they’re not anymore in there but they have an office in America. To make a long story short, I found out that these Chinese were released from the hospital, and they walked back to China. Aaron Elson:He walked from Rangoon to China?

Karnig Thomasian:Yeah, that means over the Hump, well, they’d probably go to the Burma Road; that’s not a very good place, there are a lot of pirates there. It’s not safe just because the Japs are gone. They’ve got a lot of other things, problems. God knows if he ever got back.

I wrote back and said he is walking back. I mean, you’re talking about thousands of miles. That’s how they must have gotten there in the first place. Can you imagine? Anyway, that was a sad thing for me, I couldn’t come to peace with it somehow. The full interview with Karnig is at my web site tankbooks.com, and Karnig has also written a book about his experiences, "Then There Were Six," which is available at amazon.com. A little more, however, on the etymology of "Extract Digit." According to Eric Partridge's Dictionary of Catch Phrases, Prince Philip used a variation of it in a 1961 speech on British industry, he said "It is about time we pulled our fingers out!" Fast Forward to earlier this year, and Tiger Woods, according to the blog golfbytourmiss.com, sent an "extract digit" text to Rory McIlroy: Tiger Woods Sends ‘Extract The Digit’ Return Text Message To Rory McIlroy. by Bernie McGuire New World No. 1 Tiger Woods sent struggling Rory McIlroy a timely text message ahead of next month’s Masters – ‘Get your finger out of your ass and win this week’s Shell Houston Open’. McIlroy is returning to the PGA Tour for a first time in a fortnight and in his final tournament ahead of the April 11th starting first Major Championship of the season at Augusta National. The 23-year old Northern Irishman tees up in America’s fourth largest city having broken 70 just one in nine stroke play rounds including a pair of 75s to start his new season in Abu Dhabi. And on Monday, McIlroy’s 208-day reign as World No. 1 ended when Woods captured a record-equalling eighth PGA Tour event in capturing the Arnold Palmer Invitational in Orlando. As McIlroy took to the Redstone course in suburban Humble, Woods helped lead his Albany team to success in the Tavistock Cup in Orlando. However before teeing-up in the Singles shootout he received a congratulatory text message from McIlroy. “I thought I would just let it all sort of die down a bit after his win yesterday so I texted him this morning. “I hadn’t spoken to Tiger for a couple of weeks but I sent him a text this morning congratulating him on his win and saying: ‘Well done’. “Tiger got back to me and told me to get my finger out of my ass and win this week.” And when www.golfbytourmiss. com mentioned the text to McIlroy later while he was playing a practice round, McIlroy admitted that was a toned down version of what Woods texted him. - - - Help keep blog posts like this coming by visiting my crowdfunding campaign, checking out the "perks" and making a small donation. Thank you, Aaron Elson

Published on June 28, 2013 16:15

June 20, 2013

Bandits at 6 o'clock

“It was just like the battle in 'Wings,'” George Collar said of the Kassel Mission of Sept. 27, 1944. “You’d hear those guns shooting and you could hear stuff blowing up and planes blowing up and bomb bay doors come floating by, and you could see the fighters sailing in on these guys. It was just like the movies. Better than the movies.”

“Wings," a silent film about aerial combat in World War I, was the first movie to win the Academy Award for Best Picture, in 1927.

Collar was a bombardier on the Kassel Mission. His B-24 was one of 25 shot down that day and he became a prisoner of war. Bill Dewey, the pilot of one of the 10 bombers that survived the initial battle, once mentioned that he'd probably seen "12 O'Clock High" two dozen times.

The Kassel Mission was supposed to be what was called a “milk run.” It turned out to be one of the most spectacular air battles of World War II.

These are some descriptions from the survivors:

• “The tail gunner broke in on the intercom with ‘Bandits at 6 o’clock level, ten or twelve across.’ ”

• “Planes were going down – some in flames, others just exploding. The air was full of 20-millimeter shells. I thought the whole German Air Force was in the air at the same time. The first pass that they made took most of the squadron with them.”

• “There were planes blowing up. I saw engines go flying out of their holes. I saw parachutes. Parts of planes.”

• “The leading Liberator, on fire from nose to tail, came swinging toward us like a severely wounded animal, then peeled away as if to pick a spot away from us to die. The next bomber moved up in its place. Then we were hit ourselves.”

• “I looked east and saw what looked to me to be over l00 fighters coming down in waves. I saw planes on fire, fliers bailing out, many with chutes also on fire. It couldn’t have taken over a few moments and looked to me like the whole 445th was wiped out. It is a memory and a vision I’ve carried for over 50 years.

• “The Liberator with the engines on fire on the left wing came up from below us to explode after it had reached our level. A human form fell out of the orange colored ball of fire. As he fell through space without parachute or harness, he reached up as if to grasp at something.”

• “I looked down on the lead group and there’s a bunch of FW-190s coming in, nine or ten of them abreast, shooting at them. And by that time we’re getting hit.”

• “The 20-millimeter shell tore through the bomb bay, ripping off the doors and severing fuel lines. Two fires started simultaneously in the bay. What strange mystery of fate kept us from exploding I’ll never be able to fathom. The engineer threw off his parachute, grabbed a fire extinguisher, and put both fires out before the 100-octane gas had been ignited. Then he attended to the leaks from which fuel was pouring out like water from a fire hydrant. Gasoline had saturated the three of us in the ship’s waist, and we all had a difficult time moving about. The two waist gunners were slipping and sliding as they sighted their guns.”

George Collar and Bill Dewey devoted much of their lives to gathering documentation and preserving the history of the Kassel Mission. Together they formed the Kassel Mission Memorial Association, which, along with the efforts of German historian Walter Hassenpflug, was responsible for placing a monument in Germany with the names of 123 Americans and 18 Germans who perished in the battle. Collar and Dewey have both passed away, and Hassenpflug, who was an 11-year-old boy at the time of the battle, is in poor health. The so-called "next gen," or next generation, with people like Linda Dewey, Bill's daughter; and Doug Collar, George's son, spearheaded the formation of the Kassel Mission Historical Society.

It was the dream of Bill Dewey and George Collar to one day write a book about the mission. Dewey hoped to model it after "Black Sunday," a coffee table tome about the Ploesti raid.

As was often the case with George, the conversation went off on an occasional tangent. One such tangent involved the Dessau Mission of Aug. 16, 1944, five weeks before the Kassel raid.

“That Dessau Mission was my first mission,” remarked Bill. “I didn’t know any better. I guess that was the worst flak anybody had ever seen, because it was from railroad guns [antiaircraft guns on rail cars along the path the bombers were flying], and I didn’t know that that’s not the way it would be for all 35 missions.”

“We never got to the target that day,” said George. “We had supercharger trouble and we started back. And in the meantime there was a guy in the high high right squadron who flopped over and came right down on top of Captain Carlisle’s plane, and as they came past, they almost wiped out Baynham’s plane. And they think the plane was upside down because they found footprints on the ceiling. And the bombs went up and came down in the bomb bay. They hadn’t dropped the bombs yet; they were flopping around on the shackles.”

“One of the best stories we’ve got to put in,” George said a bit later, “is that story about Hunter’s crew, when they crashed in France [on the Kassel Mission]. They got hit in the gasoline tanks and gasoline was siphoning out of the bomb bay and coming up into the photographer’s hatch in the waist, and they said they were sloshing around in six inches of 120 octane gas. And there was a guy that deserved a medal – and he got one, too – a guy named Ratchford – he was the engineer. He went down in the bomb bay, imagine that, with gasoline shooting all over, and he repaired the leak. And they crash-landed, and they never even caught on fire.”

“You know, these stories,” Doug Collar interjected. “I remember at Friedlos, getting ready for the ceremony [at the monument in Germany 1990]. I’m kind of eavesdropping, and these 18, 19 year old GIs are saying, ‘Do you believe these old farts?’

“One of them says, ‘I can’t believe it, these guys are up there flying around, shooting .50-calibers at each other, no pressurized cabins. Jesus Christ!’

“I’m listening, and the thing about it is, when you tell the story, the guy flying upside down, the footprints on the ceiling, bombs flying around [in the plane], gasoline pouring out: this is the stuff that the average citizen has no comprehension of today. They see pushbutton warfare in the Persian Gulf – it’s all electronic. And I think this is the essence of a lot of these stories. These are unbelievable today.”

After a few more anecdotes, the discussion took a somber turn, as the two principals placed the mission in the perspective of military disasters.

“I’ll tell you what I think about this mission,” George said. “It was a big defeat for us and nothing to brag about, and I always said there was never anything written about it because they were trying to forget it.”

“That’s right,” Bill said. “A coverup.”

“I don’t know if it was a coverup,” George said. “They just said, 'Let’s kind of wash it under the rug.'”

“Yeah,” Bill said. “Like that battleship that went down in ’45. The Indianapolis [actually, it was a cruiser]. That was a terrible thing.”

Doug Collar suggested stressing the teamwork among the crews.

“The thing that comes across time and again,” he said, “is that this is a team operation. It’s the training, but also the esprit de corps. Everybody had a job to do, they knew what they were supposed to do. I think that comes across on the Kassel Mission a lot.

“Another thing the team concept manifests itself in is in what’s happened since 1986, in the fact that these guys are like a family 50 years later.”

One valuable member of that family, Bill and George pointed out, is the young Belgian Luc Dewez, the author of the first, and so far the only, book about the Kassel Mission, “The Cruel Sky.”

“Luc, he calls me, my … what does he say in here?” George said, opening his copy to the dedication. “‘To George. Don’t stop talking. Don’t stop researching. Dear boyhood hero. Dear friend. From Belgium. Stay my wordy friend.”

“When I read that I thought, ‘You sonofagun!’” George said. After a round of laughter, all agreed that Luc meant “My worthy friend.”

“You know, another thing about this team concept,” Doug said. “When I introduced Luc at the banquet [at the Savannah reunion of the 8th Air Force Association in 1999], I made remarks about how this is a team effort and the Allies are part of this, and he was representing the role of our Allies in Belgium: his father fought in the underground. Well, he didn’t show up at the Saturday night banquet, and everybody was worried about him. Then we came back, and when the bus came in, he was standing there passing his book out at 11 o’clock at night in the hotel.

“I said, ‘What happened to you?’

“He said, ‘Well, you mentioned we’re part of a family, part of a team effort.’ And he said, ‘Web Uebelhoer’s legs were swelling up and he needed medical help, so I stayed here with him. I’m part of the team.’” [Web Uebelhoer was the pilot of the deputy lead plane on the Kassel Mission, and had suffered a stroke and was in a wheelchair at the reunion.]

Despite the exhaustive research conducted by George and Bill, there was actually a bit of serendipity involved in the formation of the KMMA.

“I’ve got to give credit to my wife for this,” Bill said, “because we were at a reception at Norwich City Hall [in England] and she heard these two people talking about going back to Germany and meeting the German pilots, and it was Frank Bertram and Reg Miner talking with some other people. She grabbed ahold of them and said, ‘My husband always wanted to meet the German pilots.’ And so she introduced me to Frank, who had been in our 445th but I didn’t know him. So I’ve got to give credit to my wife.”

“I remember back in ’87,” George said to Bill, “we went to that mini reunion down in Dayton and I met you.”

“You said, ‘I want to see you,’” Bill replied. “You were sitting in the auditorium.”

“And you know,” George said, “the funny part of it was, after Woolnough [editor of the 8thAir Force News] published the “Kassel Mission Reports” [actually, KMMA published the “Reports” that were articles originally carried in the 8thAir Force News], there was a letter in the 8th Air Force newsletter from a guy who said he had a friend that was killed in the Kassel raid and somebody ought to do something about putting up a monument, so the nucleus of the monument really started with him.”

“He was a B-29 gunner, wasn’t he?” Bill recalled.

“They’d gone through gunnery school together,” Doug said.

“He said, ‘If anybody wanted to put up a monument, I'd be glad to donate,” Bill said. “And that's where I got the idea of a monument.”

“Anyway," George said, “I looked at the name. There was nobody with that name on the Kassel Mission.”

“We never heard any more from him,” Bill said.

“He never sent in his money!” George said.

The Kassel Mission Memorial in Friedlos, GermanyFor more on the Kassel Mission, please visit kasselmission.com

The Kassel Mission Memorial in Friedlos, GermanyFor more on the Kassel Mission, please visit kasselmission.com

Published on June 20, 2013 19:05

June 1, 2013

A Medic's Story

Following is an excerpt from "A Medic's Story," by Edward Madden, as told to me during a 2000 interview at the 90th Infantry Division reunion in Charlotte, North Carolina. "A Medic's Story" is available for Kindle for $1.99 at amazon.com. After the Normandy peninsula was cut off, they put us into a holding position and we were put onto this farm. We were there for almost two weeks, in a holding position. And one day, July the 1st, the Germans decided they were going to put some artillery into the place. There were two girls who lived on the farm. One was 14 or 15, and her sister was 16 or 17. They were out in the field, milking the cows at about 5 o’clock in the afternoon, when the Germans put the shells in there. The shells landed real close to them, and a couple of the cows were killed, and some of the shrapnel went through the older sister’s heart and killed her. And the younger girl had both of her legs taken off below the knee, both of them, and one of her arms was pretty badly shattered. And I went out and picked her up and brought her into their house. I treated her, then I called and had her evacuated back. The very next day we moved out, and I never heard anything about her until later on in the year, in December or so, the Stars & Stripes came out and there was an article in it showing her with Air Corps people. And what they did was they came in, and they built a landing strip right near the farm. They found out about her, so they went back to the Army hospital that they had her in, and the Air Force took her out of there – with permission – and they brought her back to the farm and they built a tent for her. They had their doctors take care of her, and eventually they ended up buying her prostheses for her legs. When the Air Corps – these were fighter planes, P-47s – moved forward to keep up with the infantry, they were able to carry her in their planes because they got written permission from General Eisenhower to take her with them. And she met Eisenhower, he came over and talked to her. I sent the article home, and I didn’t think anything about it. Then in 1985, when I was going to go to Europe, I wrote to Henri Levaufre [a Normandy historian who has assisted many 90th Division veterans] and I told him about her and asked him to find out if the woman is still alive. He wrote back to me and he said, yes, he found her, that she lives only a few miles from where Henri lived. So he said when you get to the hotel – we told him what hotel in Paris we were going to be at – he said he would leave a message for me so I’d know where she lives. So when we got into Paris we got a message stating that her daughter – without the legs but with the artificial limbs; she married a lawyer, and she had one daughter, and the daughter was going to come by in the morning and pick us up and take us to the big hospital in Paris where they take care of the people. So they took us over and we met for the first time. And she didn’t know that it was the infantry that was stationed at her farm – she didn’t remember that it was infantry, she thought there were artillery people, and she didn’t know who I was or that I had taken care of her until I explained to her; I told her that one day one of our officers was going through their barn, and he moved some hay aside and he found a German motorcycle that her brother had hidden, that he’d stolen from the Germans. I told her about that and she said, “Oh, my God, you werethere, on the farm.” And I said, “Yes, I was the one that took care of you.” Well, with all of this the Air Force had adopted her and they’ve had her come over to some of their reunions. And if you ever go to the Airborne Museum in Ste. Mere Eglise, they have a whole display about her there. I met her in 1985, and then when I went over in 1994 we stayed with her at her home for a few days and she took us around and she introduced us to the curator of the museum at Ste. Mere Eglise. Her name is Yvette Hamel. Incidentally, there’s a book, one of the fliers, he’s a doctor now, his wife met her and his wife wrote a book about her called “Sunward I’ve Climbed,” and it’s been translated into French, too. It’s an interesting book. I’ve got it. She sent me a copy, signed and all.

Order "A Medic's Story" for $1.99 from Amazon.com

Order "A Medic's Story" for $1.99 from Amazon.com

Published on June 01, 2013 18:38

May 24, 2013

Memorial Day 2013: Pine Valley Bynum

Quentin "Pine Valley" Bynum

Quentin "Pine Valley" BynumMy fellow Stuyvesant High School alum Mitch Corrado asked if he could post a brief excerpt from "The Armored Fist" on his Facebook status. I told him I'd be honored.

The selection he chose was about the reaction of Quentin "Pine Valley" Bynum's father to his son's death in combat.

This got me to thinking about Quentin Bynum with Memorial Day only a couple of days away, not that I don't think about him often. At the very first reunion of the 712th Tank Battalion I went to, in 1987, I met Jule Braatz, the sergeant to whom my father, a replacement lieutenant, reported, and Braatz told me a story about Bynum giving my dad a lift to the front in the "bog," or bow gunner's seat, of his tank.

The story was third hand, Braatz said, because Bynum was later killed. So Bynum had told Braatz and Braatz was relating the story to me. That seems like it would be secondhand, whereas me relating the story now would be third hand.

Upon arriving at the front, late in July of 1944, Bynum's platoon came to a halt and my father, to the best of my knowledge, wanted to get out of the tank to look for the platoon to which he was assigned, which Braatz, the platoon sergeant, had led into the battle.

Bynum told Braatz he urged my dad not to get out of the tank because there was still artillery or mortar shells coming in, but my father insisted on getting out of the tank and was wounded almost right away. He never did find the platoon, and Braatz would later receive a battlefield commission. My father would not return until November.

Shortly after launching my original web site, tankbooks.com, I received an email from Chris Bynum, Quentin's nephew. Chris inherited his uncle's dogtags and grew up with Quentin as his hero. I emailed Chris back and asked if any of Quentin's siblings were still alive. As a result, I went to Springfield, Missouri, and interviewed James Bynum, who was about five years younger than Quentin.

When I was a kid I wanted to grow up to be a detective, and when I did grow up and started working for a newspaper, I wanted to be an investigative reporter. Neither of those things happened, but I seem to have always had that "follow the evidence, connect the dots" instinct, not that I was very good at connecting the dots in game books when I was a kid.

Which brings me back to Quentin Bynum, and an image I'll never get out of my head but that I didn't include in the book because I never was able to corroborate it. If a movie is ever made based on "The Armored Fist," I'll suggest basing a scene on this particular image; or if "The Armored Fist" were fiction, there's no doubt it would be the climax of a chapter. But the two people who could corroborate the image -- the two crew members, that is, who survived the incident in which Bynum was killed -- are deceased. Still, a couple of the facts support the possibility that the image might have been real.

One of the first stories James Bynum told me was about how his brother Quentin died when he was an infant. James said Quentin had diphtheria, although it occurred around the time of the great influenza pandemic of 1918 so it might have been the flu, but either way, the doctor pronounced Quentin dead. Quentin's mother, however, who had, according to James, "the mouth of a muleskinner," refused to let the doctor leave, so he suggested "warming the baby by the fire of the cookstove," and Quentin came back to life.

James surmised that during Quentin's brief brush with death as an infant, he may have suffered from a lack of oxygen to the brain, resulting in a diminished mental capacity. James' evidence of this was that Quentin grew up loving to do chores on the farm and eventually dropped out of school, whereas his older brothers, and James too, all favored intellectual pursuits.

Because he enjoyed farm work so much, Quentin became especially strong. James described how one winter when Quentin was walking home from school with James and one of his sisters, both of the younger children were crying from the cold, and Quentin picked them both up and carried them the rest of the way home. Another time Quentin challenged his older brother Hugh to a contest to see which one could pull a sprayer -- a feat best managed by a team of Clydesdales -- the farthest. Quentin took one side and Hugh the other. James didn't remember who won, but it illustrated the extent to which Quentin's strength had developed.

My research, such as it is, is not linear. I interviewed James Bynum in 1997. I interviewed Dess Tibbitts, who, like Quentin Bynum, was a tank driver in A Company, in 1995. I interviewed Bob "Big Andy" Anderson in 1993.

Big Andy, who, like Bynum, was a farmboy, was talking about food when he mentioned Bynum.

"I'd find," he said, "not just me but all of us would find, what we did, was on the front of these tanks we'd put a plank, and then we'd put things up there. And we had eggs, you could fry eggs. Then in the chimneys of a lot of places you'd find hams hanging up in there. And then of course a lot of people would catch chickens and kill them and cook themselves a meal.

"Generally when you were up on the line all you got to eat was what we called C rations, but when you got back for a ten-day rest you'd do most anything. There was one time a bunch of us guys was having fun; we'd throw these hand grenades in the creek, they'd go off under water and we'd get fish. Then we got crazy enough we were taking and unscrewing the cap and knocking all the powder out, and then we'd pull the pin and toss them over to somebody. They wouldn't go off. I did that to one kid whose name was Bynum. I said, 'Here, Quentin Bynum,' well, I didn't have all the powder off so the thing exploded. It didn't have strength enough, but that made us quit doing that stuff. He could have got hit in the face."

Two years after my interview with Big Andy, I mentioned this to Dess Tibbitts.

"Big Andy said that one day he and Pine Valley were playing catch with hand grenades that they would take the powder out of," I said.

"Yeah," Tibbitts said, "and he forgot to get all the powder out of one. One time old Pine got after him with a pitchfork and I think Pine would have stuck that pitchfork in him if he'd have caught old Andy. They got plum mad down there one time fighting in the cavalry. Pine had a hell of a temper, you didn't want to fool with him.

"I felt sorry for poor old Pine," Tibbitts said, "because when we got ready to go to tank school they took all us tank drivers and sent us to Fort Knox for three months of tank training, and poor old Pine didn't get to go and I didn't find out till afterwards that he couldn't pass the IQ. They never sent him. And he resented it. Even when we went overseas he resented it. He just hated the fact that we went to school and he hadn't. Him and I were the best of friends before we went to school, and when I came back I tried to bring back the friendship again. And I wondered what the problem was, and this was the problem. They wouldn't send him to school because he didn't have IQ enough. He wasn't too well educated. But he was a hell of a tank driver and a good one."

Big Andy was in the first platoon, whereas Bynum was in the second platoon of A Company. When I interviewed him in 1992, Anderson described hearing on the radio the exchange preceding Bynum's death.

"This Lippincott," Andy said, referring to Lieutenant Wallace Lippincott, "I heard it all over the intercom. They were in this forest, and the Germans were laying artillery, and the shrapnel was coming down and hitting the tank. And this Lippincott said, 'Abandon tank.'

"And Bynum said, 'No, Lieutenant, that's just shrapnel. Just sit still.'

"'I said abandon tank.'"

And they all abandoned tank but one man, his name was Shagonabe, he was an Indian, he stayed in the tank, and he's the only live boy out of that crew. The rest of them, Bynum -- I don't know why Bynum obeyed -- but this Lippincott, if he would have listened to an older man [that is, someone who'd been in combat for a much longer time, as Bynum had], they all might have been alive today."

The next time I would hear about the incident in which Bynum was killed, all five members of the crew would be killed. It wasn't until I interviewed Charles Voorhis, who gave me a firsthand account of the engagement, that, except for the one haunting image, I got a much clearer picture of what actually happened, and learned that two of the five crew members survived.

On Jan. 14, 1945, in Luxembourg during the Battle of the Bulge, Voorhis said, "we had just three tanks" operable in the five-tank platoon, "MacFarland's [Voorhis was Sam MacFarland's driver], Lippincott's tank and another tank in the second section. We were at a farmhouse and we got orders that the infantry wanted us to go over the top of a hill. From where we were at we saw a German tank about every day come down, but they couldn't see us because of the building, and we'd try to get the tank out there to shoot at him, but by the time you turned that motor over, 52 revolutions to get all the oil pumped out, he'd be gone.

So we started out. The lieutenant was in the lead, MacFarland in the middle and the other tank behind us. We get over the crest of the hill, and there's a big woods, and MacFarland says, 'I can see the sun shining on faces over in the woods.'

"And Lippincott says, 'Put a round over the heads. See if you draw fire.'

"We put a round over their heads. Nothing happened. So we went on out to this farmhouse where the infantry was, and they said they didn't order any tanks. So he starts back again, now Lippincott's in the rear tank," because they were going in reverse.

"Now we have to go up over this hill. Those old Wright radial engines, low gear was it going up a hill. So I'm going up there, and they put a round in and hit the tank in front of us. All it did was bust his track on one side. He was still able to navigate. We went up over the hill. The next round dug up snow between our tank and his tank. MacFarland said, 'Get out of here, Charlie.' So I started up over the hill, too. That left the lieutenant's tank behind.

'We get to the top of the hill, and the lieutenant and his crew come by us on foot. Their tank took a hit. And we get down behind this building again, and here's his tank up there, smoke coming out of it, and all the guns are pointing right at us. So the gunner went back up, he's gonna pull the fire extinguisher, there's one right behind the driver. He got up on the side of the tank away from where the Germans were and leaned down in there to try to pull the extinguisher, and another round came in and took the top out of the 76-millimeter tube right above his head. So he got off, went around to the rear of the tank, pulled the extinguisher there, and the fire went out. What it was, there was an armor-piercing shell that went into the oil pan on the motor, and the phosphorous had set the oil on fire, and nothing else was burning yet.

"That put the lieutenant's tank out of commission. He got another one and the next day, they wait until dusk, the infantry liked to wait until almost dark to pull an attack.

"They waited until almost dusk, and then they pulled us out on the skyline, and the Germans opened up on us. MacFarland's tank was one of the old M4A1s, and the gun was worn out on it. When you tried to put a round in the chamber it would wobble, it had been used so much. So we got a pulled round, and we had to back up where they can't hit us, so the gunner could get out and run a ramrod through and clear the gun. And when we backed up, we could see Lippincott's tank. They were firing armor piercing rounds at it and they weren't hitting the tank. They were going over the top of it. So Mac, he called Lippincott on the radio and he said, 'They're firing AP at you.' That's the reason he gave the order to abandon tank when they took a hit.

"They were hit with high-explosive, and like you said, the driver told him to sit still, it wasn't armor-piercing. But anyway, when they took the hit, he told them to abandon tank. Four guys got out. Three on one side, and one guy on the other. And just as they got out, they took another high-explosive hit, and it killed three of them. The other guy, we didn't know what happened to him."

The crew of Quentin Bynum's tank that day comprised Lieutenant Lippincott, from Swarthmore, Pa.; Bynum, from Stonefort, Illinois, Frank Shagonabe, from Muskegon, Mich., Hilton Chiasson, from Thibodeaux, Louisiana; and Roy R. La Pish, from Pottsville, Pa.

For Chiasson, that was the fifth tank he had knocked out. La Pish remained in the Army after the war and was killed in Vietnam.

"Two or three days later," Big Andy said, "they asked me if I'd go back and identify Bynum. I would just say you could recognize the man. He was full of shrapnel, and laying in the snow."

There sure are a lot of Chiassons in Thibodoux, Louisiana, but I was able to reach the widow of Hilton Chiasson. In a thick Cajun accent, she said her husband, whose nickname, naturally, was Frenchy, never spoke about the war. In 2009 an article appeared in the Muskegon Chronicle about Frank Shagonabe. Frank's half-brother, Harlan Shagonabe, has since passed away.

This is the passage from my book "The Armored Fist" that my friend Mitch Corrado posted on his Facebook status:

"Your brother was killed in action. Do you need to go home?'

'I don't have any money, Sir.'

'We'll take care of that.'And then there's that image I was never able to verify, and can't recall who told it to me, but I know it was related by one of the veterans. As with so many things that occurred in the history of the 712th Tank Battalion, or any unit for that matter, eyewitness accounts differ, sometimes vividly, and secondhand accounts are sometimes distorted.

We were trying to comfort our mother, and ignoring our father. He'd been an old cavalryman, himself. He took me back to catch the train and we were standing on the platform. We could hear the train way down in the distance, so I knew it was time to say goodbye.

I said, 'Dad, take care of Mom, she's taking this very hard. And it's going to be rough on her.' And I looked over at him. And my father never cried. He never patted us. Now, me, I'm a crier. And I'm a hugger. I get that from my mom. And I looked over at him and I thought to myself, 'My G-d, how stupid can you be? Quentin was his son and he's hurting.' And I opened my arms and he walked into them, and we stood there and cried. That's the only time I ever saw my father cry.'"

But when James Bynum described his brother's strength, I recalled hearing one account in which, after abandoning the tank, a round came in and wounded both Lieutenant Lippincott and Frank Shagonabe. Whether Bynum was wounded as well I couldn't say, but whoever told me the story said that Bynum picked one of the wounded men up with each arm and was carrying them when another round came in and killed them all.

- - -

Published on May 24, 2013 14:54

May 15, 2013

An Oral History Audiobook Sampler

Today I'm going to don my chapeau as an oral historian, and post a the audio from a sampler CD containing tracks from several of my oral history audiobooks. The audiobooks are available in my eBay store. You can also order audiobooks by calling the oral history hotline at (888) 711-TANK (8265). Click on the links below to listen to the sampler in mp3 form. Track 1 Introduction (Aaron Elson) Track 2 Karnig Thomasian, POW of the Japanese, from "For You the War Is Over" Track 3 Sam Cropanese, 712th Tank Battalion, from "The Tanker Tapes" Track 4 Ed Boccafogli, 82nd Airborne Division, from "The D-Day Tapes" Track 5 Vern Schmidt, 90th Infantry Division, from "Kill or Be Killed" Track 6 Bob Rossi, 712th Tank Battalion, from "Once Upon a Tank in the Bulge" Track 7 Bob Cash, 492nd Bomb Group, ex-POW, from "March Madness" Track 8 Russell Loop, 712th Tank Battalion, from "More Tanker Tapes" Track 9 Jack Sheppard, from "Reflections of a Tank Company Commander" Track 10 George Collar, 445th Bomb Group, from "The Kassel Cassettes" Track 11 Jerome Auman, from "Four Marines" (c) copyright 2013 Aaron Elson

Published on May 15, 2013 06:41

April 29, 2013

A child in London - 1940

Margie Hoffman This is a guest post. On Friday, I've been invited to speak to the fifth-grade class at Hunter College Elementary School, my alma mater. I thought it might be a good idea to read the pupils a story from my original web site, tankbooks.com. I launched the site in 1997, and the following year I received an email from Margie Hoffman, asking if I would like to post a story she wrote on my site. She also sent a follow-up story which is on the site. I've lost touch with Margie, so, while the essence of the story may be old hat to my handful of British Twitter followers (okay, maybe it's two handfuls), if anyone knows of Margie's whereabouts could they please get in touch with me?A Child in London -- 1940Margaret Hoffman

Margie Hoffman This is a guest post. On Friday, I've been invited to speak to the fifth-grade class at Hunter College Elementary School, my alma mater. I thought it might be a good idea to read the pupils a story from my original web site, tankbooks.com. I launched the site in 1997, and the following year I received an email from Margie Hoffman, asking if I would like to post a story she wrote on my site. She also sent a follow-up story which is on the site. I've lost touch with Margie, so, while the essence of the story may be old hat to my handful of British Twitter followers (okay, maybe it's two handfuls), if anyone knows of Margie's whereabouts could they please get in touch with me?A Child in London -- 1940Margaret Hoffman©1998, 2009 Margaret Hoffman

This was written by Margie Hoffman, who was a toddler in London during the Blitz.

My war started when I was about three months old. My Dad had been called up into the army and my mother had been living in a small apartment in East London. The German planes had already been flying over London and dropping bombs, mainly at night. After one raid, my mother took me in the pram, to post a letter to my Dad to tell him that we were all right. While she was away, an undetected land mine exploded and the apartment was just brick dust so she returned to her father’s house in the dock area of London. This was an unfortunate move because the next thing the Germans bombed was the dock. They bombed it by day and night until even the water burned with the contents of the warehouses tumbling into the water. My grandfather had forbidden all his "children" -- all of whom were grown up with families – to go into the large warehouse down the road because he said it was a death trap. It’s funny what you do, though, to escape from noise and to get away from the scream of bombs. People crammed into the large warehouse, someone brought in a piano and local teachers and others organized singing to take people’s minds off the bombs. The warehouse received a direct hit and over 200 people were killed by blast. Others died not directly as a result of the bomb hitting them but they were crushed to death by the huge, heavy walls of the warehouse. Apparently we were three days and three nights in an underground shelter in Granddad’s garden. Crowded together, the family were not too pleased when the local police knocked on the door and made them take in two more people who had been a mile away from their home when the air raid began, especially as they were none too clean. After the dawn broke and everyone crawled out of the shelter, we were not only covered in dust but covered in fleas from our two uninvited guests! Granddad said if we stayed where we were we would not survive another round of bombing like that. He had already bought a small plot of land in Essex and built what he called a wooden holiday home there – it was not so much a holiday home as it was a two-roomed shed! But the garden was pleasant to look at, which was a good thing as we ended up with eight of us living in the wooden house and the men camped in a tent in the garden. Eventually we sorted ourselves out. Poor Mum had to live with her mother-in-law, who was hardly a sweet-tempered person, Dad’s mother, although born in England, had Irish parents and she was prone to be bad-tempered and a bit of a drama queen. She made matters worse by telling Mum all the bad news of the war, and her prediction of what was going to happen. Mum moved out and rented a small bungalow, which got us away from Nan but made it more difficult for Mum when the air raids started. By this time she had had another baby and when the siren went, my Granddad Hickman (who was kind, sweet and gentle – how on earth did he choose my grandmother for a wife?) would come round and carry me to the big underground shelter in his house, while Mum would carry the baby. The shelter was called an Anderson Shelter and was built half in the ground and half on top. The top half had curved, corrugated iron sheets, and you piled lots of earth on it and hoped for the best. It tended to be damp, and if it rained you all had to lift your feet up because the water seeped in from underneath. Grandmother Hickman had chosen the house just after the war started because of the large garden and peaceful neighborhood; unfortunately she failed to notice it was quite near the railway lines and in a direct line with the Shell Oil Refinery five miles away. Consequently, Germans coming in to bomb the oil refinery would miss and others would continue to have a go at the railway. I don’t know how old I was when we sat there listening to German planes coming over the shelter on their way to London and we then had to stay there until they came back. Of course if they missed their target they would jettison their bombs before they were over the Thames Estuary. One day my uncle was home on leave. He was only 19, an aircraft engineer, and he was stationed in some quiet backwater. He was fascinated by the planes and my grandmother was having hysterics. "Come inside the shelter! They will see you." Uncle was a fidget and wanted to see the planes coming back so he made us all a cup of tea and we sat there until the familiar drone came nearer and nearer. Suddenly I realized, he didn’t know about the railway lines! I didn’t say anything; everybody else was getting ready with their hands over their ears when suddenly four bombs cascaded on to the railway lines now gleaming in the moonlight. It was so near the whole shelter lifted up and then went down. My uncle dived in head-first in a state of shock and our tea went everywhere. At one stage we used to go to sleep with our clothes on. We wore what was called a siren suit, which was kind of like a child’s stretch pyjamas so that we could get into the air raid shelter quickly and not get cold. One night we went to bed at about 8 p.m. – we were cold and coal was rationed and bed was the warmest place. I slept with my mother and she would read in bed. It must have been winter because it was dark – we had thick lined curtains so that the light would not show through and in a raid you just kept the lights off anyway. Suddenly the air raid siren went; I was half asleep but my mother was up and into the back room for my baby sister (I say to her now, "I don’t know why she chose you first to get into the shelter."). By the time it was my turn large lumps of jagged shrapnel were clattering on the top of the shelter and the ground, my sister was crying, and my mother was frantic to get me, but I didn’t care: I was warm and probably tired anyway. Suddenly the railway lines got hit again, the house shook , two windows broke, then my mother came rushing in. In the explosion the vibration had shaken open the wardrobe door, my mother walked straight into it and walked around holding her head. I laughed and laughed! It was like something out of a Charlie Chaplin film. She was so mad, she clouted me round the head and said, "See if you think that’s funny." We rushed into the shelter, she a nervous wreck and nursing her head and my sister screaming. Suddenly I looked up and saw in the sky a long object with fire coming out of the back of it, but really quite close. "Isn’t that wonderful?" I said. "Yes, so wonderful, that is what is going to kill us all if you don’t get inside." The V1 was certainly a marvel of German technology but we all knew that as long as you heard the engine you were safe; once it cut out, its descent was rapid and it could take out six houses.----- My children asked me what our food was like – pathetic is the answer. We grew potatoes and tomatoes, picked berries and swapped things with neighbours. We were rationed so severely that even now I don’t eat meat as my ration had to go to my sister who used to be ill with asthma. After the war when we came off ration, I had gotten used to not eating meat so I never bothered. For a family of three we would have four ounces of meat a week – two if it had been a difficult time for the supply boats coming in. England as an island depended on overseas help for food. If the U boats were active we all went without as most of the food went to our army. Two eggs a week or else that dreadful egg powder. I always thought our food rationing was pretty dreadful until I met my husband who was a child in Holland during the war and who really knew what starvation meant. As for our little family, Dad survived D-Day and went on with the Middlesex Regiment through France, Belgium, Holland and Germany and through great good fortune came back to us. How did the war affect him? Well, he couldn’t stand noise, we never had the radio on very loud, he would never listen to a memorial service. He would never go swimming. Years later I learned on D-Day he was dropped too far out and the vehicle he was driving was nearly submerged; he negotiated debris, burning vehicles and bodies to get his crew onto Sword Beach and then off into Normandy. While his officers were having a meeting near him, mortar fire sped over the trees killing them all in front of his eyes. His confidence never returned; he could never make a decision and was left with stomach ailments that plagued his life.He looked after us both when my mother was ill immediately after the war and our bedtime stories were Operation Overlord and the time he just avoided a mine in France. We knew all the generals and battle plans. We often spoke of old battles but he would never return to France with me. He died of a heart attack at age 69 but his wartime stories are etched in my mind forever. Margaret Hoffman

Priceless. (Well, actually it's $19.95 at amazon)

Priceless. (Well, actually it's $19.95 at amazon)Please subscribe to the Oral History Audiobooks email newsletter to keep up with the latest developments and specials.

Online Form - Constant Contact Signup Form

Web Form Generator

Published on April 29, 2013 10:13

April 27, 2013

RIP Bob Cash, 492nd Bomb Group,

Thanks to David Arnett of the 492nd Bomb Group Association for the information that Bob Cash passed away on April 23. Bob was a radio operator on a B-24 and a former prisoner of war. Ray Lemons of the Kassel Mission Historical Association set me up with an interview with Bob when I visited Ray in Dallas in 2010. Here's an audio excerpt from that interview with a transcript of that section:

Bob Cash, Feb. 13, 2010 Bob Cash: We had marched, as I say, to the little community of Mehlbech and were starting back east again, and most of our guards, most all of them had abandoned us. And we were in a barn, and I couldn't go another mile. I was, my stomach was just killing me, and it was a combination of eating sugar beets and raw potatoes and everything raw, and I guess if I hadn't been so damn young, most of us would have died. But we marched out, three sets of German guards, and most of those old boys were older than we and maybe in their forties, up in their fifties, they were conscripts, they were just suiting up anybody, kids from 15 years old up, but we had marched to Mehlbech, and I told Ed, I said, "I can't go any further. I'm gonna just have to take my chances and if they push us on, they're just gonna have to shoot me, because I can't go any more."

Well, he was, this was the day, about the day before we were liberated, and he was out foraging for food. And he'd gone to a farmhouse and they'd given him a little bread and turned him out, and he saw a chicken hatch over there and he went over there and thought maybe he could get some eggs or something like that, and he heard this tank fire. It was Monty's 11th Armored Division coming over the hill and they lowered that 88, you know, and he managed to jump out of that chicken shack just in time because they leveled it, they just blew it to pieces. And he rushed back and told me about that and I said, "My god, I wasn't that hungry." He was looking for something to eat. But when they did come over the hill and down into this little village, that was a second coming. I don't know how, how the guys spent five, six, seven years in the Pacific, there weren't any that long too in Europe, but I don't know how in the hell they stood that. Of course they were stationary most of the time, and if you're not, if you're dormant, you can last a long time. But put you out on a 800-mile march ... I'm sorry, it's been 64 years ago ... 65 years ago ...

Aaron Elson: It's got to be like yesterday when you think about it.

Bob Cash: Well, the thing that, the thing that got me, you wondered how come you got through something like that, and why the Lord allowed you to come home and get to your family and start your family and so forth, and so many of those kids never had a chance to do that.

Aaron Elson: You must think about that ...

Bob Cash: I think about it every day. Every day. And mainly my crew. A couple of years ago we were in, someplace up in Ohio, close to Trotwood, where my gunner that I saw laying there dead, his sister, he had two sisters and a brother that came to this, I invited them to come over and have dinner with us and so forth, I got their names, and we had a nice chat with them, you know. I couldn't tell them anything about Bill except that he was in the back end of the plane and that I did see him and that he must have died quick. And he rests in Liège.

Aaron Elson: And his name was ...

Bob Cash: His name was Bill Mendenhall. He was from Trotwood, Ohio, I think it was. We were in Dayton, that's where we had our, he wasn't too far from there, it was on the outskirts of Dayton, Ohio.

Aaron Elson: Who else was on the crew?

Bob Cash: My crew members were Bill ... lord ... my tail gunner, the reason I think that plane blew up because it was hard for him to get out of that, he was a pretty chunky guy anyway, and when he got in that tail turret, you almost had to help him out. But he was from Denver, and his body was recovered almost three months after we were shot down, he had washed ashore in Osterdorp, Sweden, and he was identified and buried over there. And Osterdorp is right on the Baltic coast there. The other gunner, my nose turret gunner, he was a boy from Myrt, Mississippi, he was a country boy, too, and he's unaccounted for. My co-pilot's name was John Bronson, he was buried over there on the island north of, he was recovered and was buried over there on the island of not Rugen, but it was out off the north coast of Germany. This is between, an island, pretty good size island, that we had to fly over, it's not on that map, it's off the map, but it's a pretty good size island out there by itself and then you've got Sweden to the north.- - -

Please subscribe to the Oral History Audiobooks email newsletter: Online Form - Constant Contact Signup Form

Web Form Generator

...Priceless (actually $17.69 at Amazon)

...Priceless (actually $17.69 at Amazon)

Published on April 27, 2013 16:28

April 17, 2013

The Angel of Bastogne

Renee Lemaire With Memorial Day and June 6th just around the corner, I've added a thirteenth interview to my collection "The D-Day Dozen: Conversations With Veterans of the Longest Day, the Huertgen Forest and the Battle of the Bulge."

Renee Lemaire With Memorial Day and June 6th just around the corner, I've added a thirteenth interview to my collection "The D-Day Dozen: Conversations With Veterans of the Longest Day, the Huertgen Forest and the Battle of the Bulge."The interview is with Dr. John T. "Jack" Prior, whom I met while I was teaching journalism during a one-semester fellowship at Syracuse University in 2005.

The book is currently available for Kindle and will soon be available in a print edition.

It also includes a new preface.

Preface to the D-Day Dozen: Conversations With Veterans of the Longest Day, the Huertgen Forest and the Battle of the Bulge

“You’d think we were going on a three-day pass,” Chuck Hurlbut said. “Guys start shaving, combing their hair. One guy’s putting on cologne. I and a lot of my buddies had a goatee, so we spent several minutes making sure that was just right.” The men of the 299th Combat Engineer Battalion were not going on a three-day pass. They were getting ready to be sent down the cargo netting draped over the side of the Princess Maude, a converted channel steamer, into landing crafts destined for Omaha Beach in the predawn hours of June 6, 1944. Hurlbut, a young Pfc. from upstate Auburn, New York, took out some photographs of his family and looked at them. And he re-read General Eisenhower’s letter to the troops, the one that begins “You are about to embark on the Great Crusade.” “I’m looking at this stuff,” Hurlbut said, “and my buddy comes up behind me. He had on the ugliest, gaudiest, most outlandish necktie I ever saw in my life, and he was going to wear it on D-Day. We chuckled a bit, and we thought about all the things we went through, and what we’re gonna go through together. We planned a trip, what we’re gonna do when we hit Paris.”

Jack Prior was a 28-year-old battalion surgeon in the 10th Armored Division. When the Battle of the Bulge broke out, he was in Noville, Luxembourg, about five miles northeast of Bastogne. “It was like an old-time Western,” he said when I interviewed him in Manlius, New York, in 2005. “They were fighting in the streets. All of a sudden I began to see head wounds, I saw belly wounds, chest wounds, lots of fractures. We were overwhelmed with casualties. I began sending them back, but all of a sudden we had no transportation. My halftrack was hit, so I had no way to get people back to the hospital. And the casualties kept increasing. They blew the second story off the building. We were crawling on the floor to treat the patients.” Soon the 101st Airborne Division arrived in trucks, rather than by parachute, and they were able to get Dr. Prior and his staff, along with the wounded, into Bastogne. Prior set up an aid station in a garage, but was unable to heat it during the brutal cold of the European winter. “I kept getting casualties,” he said, “so I went to a three-story building. I had maybe 80 patients. I took two buildings. In one building I had the most severely injured cases, and in the other I had the walking wounded, the fractures, and the psycho cases, which we called combat fatigue in those days. And at this time, I’ve told the story many times, two Belgian nurses appeared. They were in their twenties, and they asked if they could help. And I want to tell you, we needed help. They were welcomed. One was Renee Lemaire, and the other was Augusta Chiwy.”

“My dear good Ewald,” the letter begins, “It is Friday morning, half past eight. I want to hurry and write you a nice letter. I received your dear letter yesterday and was very happy to hear from you my love, and to have heard what you did Easter Day. But now I know that you have seen the great lovers on the screen and yet you didn’t mention a bit about love in your letter. What do you do in your visits to the movies? Do you sleep while the picture is on? With whom do you usually go out, or do you go out alone? Dear Ewald, when you write, please don’t complain about your food openly. Just because your officers receive better food than you do, remember, you’re the dumb one when you start to get hotheaded. Therefore, my sweetheart, don’t write about these matters openly. ...” The letter was found in a German gun emplacement during a trip to Cherbourg by the captain of the USS Butler, a destroyer that took part in the D-Day invasion. It was translated by a member of the Butler’s crew and a copy was given to Felix Podolak of Garfield, New Jersey, one of the veterans I interviewed in 1994.