Aaron Elson's Blog, page 13

December 31, 2016

Happy New Year from Oral History Audiobooks

The Rev. Edmund Randolph Laine

The Rev. Edmund Randolph LaineOne of my New Year's Resolutions is to advance my transcription and preservation of the diary of the Rev. Edmund Randolph Laine, pastor of St. Paul's Episcopal Church in Stockbridge, Mass., during the World War II years. Laine raised Ed Forrest, who was killed on April 3, 1945. Ed was a buddy of my father in combat, and in researching Ed's life back in 1995 I learned of the existence of Laine's diary, which the Stockbridge Library allowed me to photocopy.

As 2016 came to a close, I thought I might be able to find something appropriate in my archives, but a search of the phrase "new year" on my hard drive only brought up an excerpt from an interview with tank driver Tony D'Arpino, who described a furlough he received at Christmastime in 1945. When he left he was in the 11th Armored Regiment of the 10th Armored Division, and when he took a cab back to his barracks ten days later the sign out front said C Company, 712th Tank Battalion. Unbeknownst to him, the battalion had been taken out of the division and renamed as a separate, independent tank battalion. He was a bit confused, to say the least.

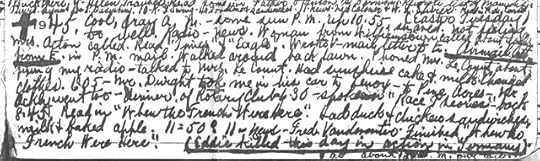

And then I remembered that a few years back I began scanning and transcribing some of the entries from Laine's diary, so I thought, I wonder what he said on various New Year's Days. I have not yet scanned the entry from Jan. 1, 1945. Ed was still alive and about to take part in the Battle of the Bulge. Following is a loose transcript of the entry for that date (you would understand why I say "loose" transcript if you could see Laine's handwriting).

Monday, Jan. 1, 1945: A very warm day - 52 degrees at noon - raining hard - very dark. Up 9:20, shaved. Radio - music (WQXR) & News). 10:25 - breakfast. Package from Springfield. 11 - Holy Com. (17) - service men & women prayed for by name. 1:45 - helped Miss F. put guest room in order. Put Christmas tree & Christmas picture away. Wrote V-mail letter to E. (No. 981). 2 - Mr. Kingdon called - father died. 2:10 - to P.O. Read "Times." Read "Times." 3 - had tomato soup, turkey sandwiches & peaches. 3:30 - "Pepper Young's Family." Raining very hard. Rec'd END. Read in "Yankee Lawyer." ("Ephraim Tutt") Dozed in chair. Read "Eagle." Read in "Yankee Lawyer." 6 - News - Quincy Howe & Bill Costello. Storming hard. Read in "Yankee Lawyer." Radio music. Snowing. 10 - News - Henry Gladstone. Had hot milk, toast & baked apple. 11 - News - John Daly & William L. Shirer.

Like many of the entries in the diary, this excerpt is full of little historical treasures. Take the line, "Read in "Yankee Lawyer" ("Ephraim Tutt."). I admit I had never heard of Ephraim Tutt, so I asked my friend Mr. Google. Who knew that only a few years ago a book would have been written about Ephraim Tutt.

Here's an article about the book: The Myth of Ephraim Tutt

Here's an article about the book: The Myth of Ephraim TuttEd Forrest was killed at Heimboldshausen, Germany, on April 3, 1945. It was curiosity about what Laine wrote in the entry for that day that inspired me to begin reading his journal. I have scanned that entry. Note the thick black cross at the beginning and what appears to be an underlined footnote at the end saying "Eddie killed this day in Germany at about 12 p.m. our time." With the time difference of about six hours, it was just about dusk in Germany when a German ME-109 fighter plane attacked some railroad cars, two of which were empty but fume filled gasoline tankers, setting off a huge explosion just as Ed, his company's executive officer, was setting up his headquarters in the basement of a nearby house.

The reason his death is recorded in the diary as a footnote is because it would be 13 days before Rev. Laine learned of Ed's death, and the entry was already pretty full, not to mention that with several lines for each of five years on a page beginning in 1941, the entry for 1945 was already at the bottom of the page.

Well, it's almost midnight. I have to make some phone calls and start wishing close friends and relatives a Happy New Year. So I'll close by saying "Happy New Year" to all my Oral History Audiobooks aficionados and thank you for your interest in these remarkable bits of history.

Published on December 31, 2016 20:48

December 23, 2016

Like listening to the MOTH Radio Hour

Karnig Thomasian

Karnig ThomasianRecently, I was interviewed on the radio on WNPR. The producer asked me to send some audio clips to give an idea of some of the interviews I've done. I put together a set of ten clips, although only four were used on the air due to my propensity to talk a little more than I should (it was an interview, after all).

However, although it was difficult to choose a set of ten relatively brief clips, the ones I selected, and many that I didn't, reminded me just how powerful these voices, and the stories they tell, are. As I listened to them, I thought I could just as easily be listening to the MOTH Radio Hour, a popular storytelling program that has recognized and promoted the entertainment value of storytelling, sharing the stories not only of comedians and entertainers, but of ordinary people as well.

Following are the ten audio clips I sent the radio station, with a little commentary on each:

Karnig Thomasian

1) Karnig, who lives in River Edge, N.J., was a prisoner of war of the Japanese after bailing out of a B-29 that exploded. In this short excerpt, in which he describes the plane carrying him home, he shifts from tears to laughter in a matter of moments. (Karnig's full interview is included in the collection titled "POW! Right in the Keister" in my eBay store.)

Dan Diel

2) Dan Diel. Dan was a lieutenant in my father's tank battalion. The war made philosophers of some of its veterans. In this excerpt he describes a sentiment that was almost universal among combat veterans: fatalism, aka if a bullet has your name on it, there's nothing you can do. (Every time I cross the street, I'm thankful my father didn't name me Peterbilt). (Dan's full interview is included in "The Tanker Tapes" in my eBay store.)

Ed Boccafogli

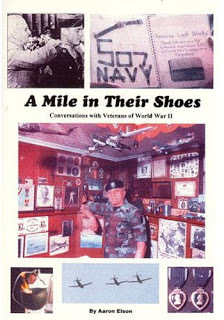

3 Ed Boccafogli. Ed was a paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne Division. In this excerpt, he describes the moment he was wounded at Baupte, France. One aspect of many of the interviews I've done is the veteran's recreation of sound effects. This always blows me away when I'm listening to it. (Ed's full interview is included in "The D-Day Tapes" in my eBay store but can also be downloaded for free from the home page of tankbooks.com

Sam Cropanese

4) Sam Cropanese. Ditto the above. Brace yourself for Sam's description of a shell hitting a tank. Sam was a Pfc. in my dad's tank battalion. (Sam's interview is included in "The Tanker Tapes")George Bussell

5) George Bussell. George was a tank driver. This excerpt shows the lighter side of the war, in which he describes going to Paris on a three-day pass with five hundred dollars and returns with 75 cents. Maybe I shouldn't have, but for the radio I edited out his descriptions of Piccadilly and Pigalle. (George Bussell's interview is included in both "The Tanker Tapes" and "The Men Who Drove the Tanks," both of which are available in my eBay store.)

John Sweren

6) John Sweren. John was a prisoner of war who endured the grueling 700 mile march across Germany near the end of the war in Europe so that the prisoners could be surrendered to the Americans and not the Russians, who would have executed all the guards. Get out a handkerchief for this one. (John's interview is included in "March Madness" in my eBay store. A transcript of the interview is available from Amazon.com in the book "Merry Christmas in July.")

Arnold Brown7) Arnold Brown. I need to re-edit the original on this now that I know a little about noise reduction; this was one of my first and favorite interviews but I rarely promote it until it's re-done. This is a very short excerpt but is pretty powerful in its statement. (This interview will be available on audio cd soon. A transcript of Arnold's interview is in my book 9 Lives)

Kay Brainard Hutchins

8) Kay Hutchins. I realized I ought to include at least one of the women I've interviewed. Most of them were widows or siblings of men who were killed, and as such would be more appropriate for Memorial Day. Kay's brother Newell was killed but he and another brother were both missing in action, so Kay joined the Red Cross, hoping she would be in England and closer to them when they were liberated. Incidentally, her maiden name was Brainard and she was originally from Hartford but her family moved to Florida when she was young. (Kay Hutchins' interview is included in "The Kassel Cassettes" and is also included in my book 9 Lives)

Patsy J. Giacchi

9) Pfc. Patsy J. Giacchi. This excerpt is a bit long, I whittled it down to about five minutes. It's one of my most popular tracks and for good reason. Patsy was a survivor of Exercise Tiger, a pre-D-Day landing exercise in which two fully loaded landing ships were torpedoed and sunk. Patsy was a little excitable, and his entire tape sounds like the actor Joe Pesci on steroids. (Patsy Giacchi's audio CD is included in "The D-Day Tapes" and his story is included in 9 Lives)

Dale Albee

10) Dale Albee. Many veterans went into schools to talk to students. Dale was a sergeant in the horse cavalry who was promoted to lieutenant on the battlefield with my father's tank battalion. (Dale's interview is included in "The Tanker Tapes.)

Published on December 23, 2016 21:40

November 20, 2016

The coal miner's daughter

My nephew, Jordan Freeman, is the co-director of the critically acclaimed documentary "Blood on the Mountain." I'm looking forward to seeing it when it comes to the area. Roger Ebert.com gave it four stars and it has an 86 percent rating at Rotten Tomatoes (that's a good thing).

This got me to thinking, heck, I wouldn't be much of a World War II oral historian if I hadn't interviewed some veterans who grew up in coal country, which, along with Midwestern farmboys, produced some of the best soldiers in World War II.

Cleo "Deadeye" Coleman, a descendent of the Hatfields of Hatfields-and-McCoys notoriety, was one of them. Myron Kiballa, whose brother Jerry was killed on Hill 122, was another. But the best description of coal country came in an impromptu interview with Eleanor Mazure, whose late husband, Frank, was a mechanic in Service Company of the 712th Tank Battalion. Forrest Dixon, the maintenance officer, described Frank Mazure as "the best thief I had," quickly adding that he didn't mean that in a pejorative sense. Rather Frank was able to steal or trade for extra spark plugs because the battalion was assigned only a limited supply. The tankers weren't supposed to idle their engines because it would foul the spark plugs, but try telling that to a crew on the front lines that might have to move on a moment's notice, or was trying to keep warm on a cold night. Thanks to Frank's ingenuity, the mechanics were able to pull the fouled spark plugs, replace them, and clean the plugs they removed. That might have gotten some men killed, Forrest said, because if their tank wouldn't run, they couldn't go into action, but it also might have saved a lot of lives.

Frank survived the war but passed away before I began recording stories of the veterans of the 712th. His widow, Eleanor, sat in on an interview I was doing with Ed Stuever, who was a maintenance sergeant in the 712th and had worked closely with her husband.

But I digress. It was Eleanor's description of life in coal country I wanted to share, so here's a transcript of that interview.

Eleanor Mazure

Eleanor MazureInterview with Eleanor Mazure Widow of Sgt. Frank Mazure Service Company, 712th Tank Battalion Pittsburgh, Sept. 1996

Aaron Elson: How did you and Frank meet?

Eleanor Mazure: We lived in the same town, a small coal-mining town in Ohio, on the same street. There were eight or ten houses on each side of the street, and he lived down at one end and I lived at the other end.

Aaron Elson: How old were you?

Eleanor Mazure: I went with him for five years before we got married, so I was 16.

Aaron Elson: Was your father a coal miner?

Eleanor Mazure: Yes.

Aaron Elson: So you must have had a big family.

Eleanor Mazure: I was one of seven children, and Frank was one of 13. But a lot of them didn=t survive until they were adults.

Aaron Elson: That must have been a tough life.

Eleanor Mazure: Very, very tough.

Aaron Elson: Was there a lot of drinking?

Eleanor Mazure: Well, that was about the only recreation that the miners had. Once they came home from work on weekends, there wasn=t much to do in a small coal-mining town in those days.

Aaron Elson: Where in Ohio was it?

Eleanor Mazure: It was in a place called Piney Fork, Ohio, and Piney Fork is about 20 miles south of Steubenville.

Aaron Elson: Was Frank older than you or the same age?

Eleanor Mazure: He was five years older than me.

Aaron Elson: Did he work before he went into the Army?

Eleanor Mazure: He worked on what they called the tipple. The tipple=s on the outside of the coal mine. He didn=t want to go underground, so he worked on the tipple where the coal came out and it was dumped into. He worked there a short period of time.

Aaron Elson: Why do you think he didn=t want to go underground? Was he claustrophobic?

Eleanor Mazure: I don=t think there was any particular reason. I just think he probably foresaw that there wasn=t any future there. And he and another fellow told us for a long, long time that they were going to go into the Army, and nobody believed them. So he and another fellow went down to the recruiting place and signed up.

Aaron Elson: What year was that?

Eleanor Mazure: He went in in 1939.

Aaron Elson: Why do you think nobody believed him when he said he was going to go into the Army?

Eleanor Mazure: Because in a coal-mining town in those days there wasn=t any future. If you started to be a coal miner, that=s who you would end up.

Aaron Elson: Did he and his friend go into the same outfit?

Eleanor Mazure: No. Frank went directly to Fort Knox. And from Fort Knox, I don=t recall if it was in the first or second year, but he was sent to Y wait a minute, first they were in cavalry. Because they wore those pants, you know, the jodhpurs, I think they=re called. But then later on he changed to armor. He was sent to Aberdeen, Maryland, to ordnance school, and that=s where he learned how to be a mechanic on the tanks, and then from there he graduated. Okay, we were supposed to get married on the post but they only got three days=leave in between Aberdeen and Pine Camp, New York, so we just got married in Steubenville, and we went up to Pine Camp on the bus. We got married November the 3rd, 1941, one month before Pearl Harbor.

Aaron Elson: How much did Frank make? Was he a sergeant yet?

Eleanor Mazure: Well, he went in as a private, and each step Bhe didn't skip any, and he wasn't elevated on his merits, there had to be openings Bplus I encouraged him. I always said, AYou can do better.@ So he ended up being a master sergeant in Service Company. A month after we were married, the war started, and that changed everything. In the beginning, he was making $21 a month, for a long, long time. I don't recall how much more he made when he was a Pfc, but he was already a master sergeant when he went overseas.

They wanted him to go to officers candidate school, but he didn't want to get out of his unit. He enjoyed his men immensely. When he came home Bthis doesn't have anything to do with this period, but when he came home from service, I don't know if he was shellshocked or what, but he used to get up in the middle of the night and start packing his barracks bag and crying, AI=m going back to my men. I=m going back to my men.@He cared so much about the men.

Aaron Elson: How did Frank propose to you?

Eleanor Mazure: When he went into the service, he said, AWhen I get through with all my schooling and everything, I=m going to send for you.@So we got engaged through the mail. And he sent me my ring through the mail. After he got out of school, he came home and got me and we got married in Steubenville, and then we just got on the bus and went to Pine Camp.We got there too late to find accommodations on the post and we didn=t have a car. We found a place in a small town about three miles from the post, I don=t remember the name of the town, and Frank walked up there every day. I got privileges to go on the post and shop.We lived with some real nice people. They made accommodations for us upstairs in their home, and it was really great.One thing I did, I felt sorry for all these fellows because I knew eventually they were going to go overseas, so every Sunday Frank invited at least three fellows over for Sunday dinner. In the afternoon I would cook something that he really liked. I cooked cabbage rolls, spaghetti. I just felt that was my little contribution toward making Frank happy before they went overseas.When we left Pine Camp, we went to Fort Knox. And then from Fort Knox, we were transferred down to Camp Gordon, Georgia, and then to Fort Benning. And from Fort Benning they were transferred to Fort Jackson, and that was where they left from.

Aaron Elson: What was your maiden name?

Eleanor Mazure: My maiden name was Berdjar.

Aaron Elson: Is that Polish?

Eleanor Mazure: Slovak.

Aaron Elson: And Frank was what?

Eleanor Mazure: One of his parents was Polish and one was Hungarian.

Aaron Elson: How many generations back did your family go in the States?

Eleanor Mazure: My father came over from Czechoslovakia when he was seven years old, and my grandparents on both sides came from Czechoslovakia. My mother was born in Johnstown, Pennsylvania. But all of my grandparents, when they came from Europe, we don=t know that history, but they all came to Pennsylvania and maybe were coal miners for a short period of time, and then they transferred to Piney Fork, where we all lived. That was the Hannah coal mining area that, everybody knows it, it was a real big operation at the time. They=re no longer in operation.

Aaron Elson: Were there strikes?

Eleanor Mazure: Yes.

Aaron Elson: And accidents?

Eleanor Mazure: Yes. When there was an accident, they would ring this loud whistle. The whole town heard it, and then we knew that there was a tragedy. The men used to go in on cars. They=d sit in these cars, they were open cars, and it would take them into the mine and then bring them out at night. It=s hard to imagine, but the coal miners never saw daylight for many months out of the year, because they would go in in the morning when it was dark, and when they came out at night it was dark. And, this is funny but the miners always had different omens. If sometimes they would see rats in the mine, and the rats would start running, then they knew there was going to be a cave-in. And there were several other things that they knew, and then they would clear the area. In the beginning, miners were very low-paid, but later on Ba lot of people didn=t like John L. Lewis but it was because of him that the miners gained some benefits, so we have to thank him. But Frank didn=t even have, he didn't have a high school education, because in those days, the high school was seven miles away and you didn=t have the money to pay the bus fare to get to, you know, so he only went through eighth grade but he did work his way up, I have to say that. Nothing was given to him. He worked. I even asked Dixon at the last reunion, I said, AHow did you ever choose Frank to be your motor sergeant?@And he said, ADo you think I=d pick somebody that didn=t know anything? I picked the best.@

Aaron Elson: How did you feel when you knew he was going to go overseas?

Eleanor Mazure: Well naturally, we all felt very badly. We took it kind of hard.

Aaron Elson: Were there other wives in the same...

Eleanor Mazure: Yes, I came home, we departed, we stayed there as long as we could in Fort Jackson, we stayed there until the last minute, in fact the last, they didn=t know exactly which day they were gonna leave, so this one particular night it was raining as hard as it could rain, so a couple of us went over near that area and the fellows somehow, I don=t know if they came over by the fence or what, I don=t recall, but they snuck out to see us for a little bit, and that was the last time we saw them. So I came home on the train with Fernandez=s wife and Mrs. Greeley, West Virginia there. And that was it. But naturally we felt badly, and the thing of it is, we had been there nearly like, let=s see, like three years, and I was pregnant, I was gonna have a baby when he went over, so naturally, you know, that was... So anyway, my first son, his name is also Frank, and he was born while they were in the thick of the fighting.

Aaron Elson: So you were pregnant when he went overseas?

Eleanor Mazure: Yeah, see, because we didn=t know they were gonna go. So ...

Aaron Elson: Is he still alive?

Eleanor Mazure: My son?

Aaron Elson: Yes.

Eleanor Mazure: Oh yes.

Aaron Elson: Because I=ve only met Clark.

Eleanor Mazure: Well, this other son, he lives about, oh, 35 or 40 miles from me, he=s also a Vietnam vet. But Clark=s the one that=s interested in the history.

Aaron Elson: Okay, so you were pregnant with Frank Junior.

Eleanor Mazure: And then they went overseas, yes. And he was born on July the 9th, and they were in the thick of battle, because they had, I=ve forgotten the name of it but they had some way that you could send a telegram to the fellows to let them know. So I was in hospital, I remember when I woke up I kept saying, ADid you let him know? Did you let him know? Did you let him know?@ But he didn=t get the message for three weeks, because they didn=t know where they were. So, he said all his friends were congratulating him, AI didn=t know what they were congratulating me for because I hadn=t seen it.@ And so Frank was a year old the week that he came home.

Aaron Elson: Who named him? Did you decide in advance?

Eleanor Mazure: Well, I guess we sort of decided together. I could tell you something about that name. We named him Frank Fillmore, for the middle name, and Fillmore was one of Frank=s good buddies. I never got to meet the man because he never came to any reunions, but he thought so much of the man he said, AWe have to name our son Fillmore,@so that was his middle name, but I never got to tell that man, they tell me he=s sick, I don=t know.

Aaron Elson: That would be Fillmore Enger.

Eleanor Mazure: Yes.

Aaron Elson: I=ve never met him.

Eleanor Mazure: I don=t know, what else can I tell you?

Aaron Elson: While he was overseas, did you have contact with his mother?

Eleanor Mazure: Oh, his parents were already passed away.

Aaron Elson: Really?

Eleanor Mazure: M-hm.

Aaron Elson: Both of them?

Eleanor Mazure: M-hm.

Aaron Elson: So I guess his father died young...

Eleanor Mazure: No, his mom died, she was kind of young, she had severe heart problems. His dad was older, but they weren=t that young. They were older.

Aaron Elson: So both his parents had died. It must have been pretty nervewracking for you with him overseas. It must have also been very tough. How did you support yourself, and survive? Did he send money home?

Eleanor Mazure: Yes, in those days, though, you know the pay was so low, well, I came back to Cleveland and I found a little two-room, through one of my relatives I found a little two-room efficiency, and I survived. I managed. You manage. You did without. You were used to doing without if you were a coal miner=s family, you know, you did with what you had and you made the best of it.

Aaron Elson: Now what was that about a three-cent loaf of bread?

Eleanor Mazure: Oh, up in Pine Camp they had a commissary, you know, it was the men could do some of their shopping there, so I got a little ID, it=s a metal pin with your picture on it, and I would go up there, I would walk up, and they=d let you in once they saw your ID, and the bread was three cents a loaf. And I don=t remember too much about the other prices but they weren=t much. But you know, how much could you carry? How much could you carry home? I really, Frank loved the Army, and I loved it too. I love traveling around.

Aaron Elson: What was that about the smoky trains?

Eleanor Mazure: Oh, you asked me how we got down to the different camps. Well, during the war, everything was used up for the war effort, so in my train to Louisville train it was so smoky and so dirty and so puffy, that when we got down there we were loaded with soot. But that=s the way we had to travel.

Aaron Elson: Now Frank Junior, he went to Vietnam?

Eleanor Mazure: It was almost like a repeat. Yeah, he was in the Reserves, okay, for like six or seven years, and his unit from Cleveland was the 233rd Quartermaster Corps, and there were about 230 fellows who were called up, and he was one of them. So in his case also, he had been married I don=t know, a year or two, and when he went overseas, his wife was pregnant. Not expecting to go. So his little girl was a year old when he came home. It was unreal.

Aaron Elson: Now you don=t talk about him much.

Eleanor Mazure: Well, I didn=t realize I could contribute something, because Clark is the one that=s into the history.

Aaron Elson: Was Frank Junior, did he come home, was he affected by being over there?

Eleanor Mazure: Well, he=s okay, I mean, you know, he came home alone.

Aaron Elson: Alone?

Eleanor Mazure: Sure. They came home one by one. There wasn=t anybody to greet them like there was the other fellows. But he was all right. I think he=s a nervous person, but other than that, he didn=t use Vietnam as a crutch, like some fellows do, he just said, well, you have to go on with your life, pick up the pieces and do the best you can do. So I don=t really mention him because I don=t ...

Aaron Elson: And when was Clark born?

Eleanor Mazure: He=s six years younger than Frank, so he was born in 1951.

Aaron Elson: Frank Senior, he really loved the Army?

Eleanor Mazure: Oh, he loved the Army, yeah. He would have stayed in, but he wanted to come home and see his child. And then they were going to send them over to the Pacific, and I think the fellows thought they had enough, being on the one front. But I have to say that he was very happy when he was in the service, and if he could have stayed in he would have been the happiest man on this earth because he just loved it so much, I can=t stress that enough.

Aaron Elson: How did he pass away?

Eleanor Mazure: Oh, he had a lot of things wrong with him. He was in the VA Hospital for a long, long time. He had hurt his foot in one of the tanks once, his knee, and he never put in a claim for it. So periodically, his knee would give out and I thought he was faking. But he ended up, he had a brace on his knee, and I think he had a stroke, and he had all kinds of things wrong with him, so then, you know, it just took its toll on him, and that was it. He had numerous things wrong with him, so they just all, you know how they take their toll and add up, and he just, one morning, he just keeled over, he was sitting in a restaurant, and he just keeled over.

Aaron Elson: How old was he?

Eleanor Mazure: He was in his, you know I get a little confused on all these people that died because my little granddaughter died when she was 2, Clark=s little girl died when she was two years old. And Mom died and Frank died, they all sort of died real close together, I=m getting the dates mixed up, not because I=m forgetting but it=s just such a ...

Aaron Elson: But what year was that, then...Clark=s little girl died or Frank=s little girl?

Eleanor Mazure: Clark=s. Clark=s little girl died when she was 2. She was born with a congenital heart defect, and she had a couple of heart operations, and she survived the one when she was five months old and later on another one, but when she was two then, she had another one, and she didn=t survive that one. She was in RB and C in Cleveland, which is a special children=s hospital, but she didn=t make it, so that=s been one heartache, you know, he=s carried, but he has three other children.

Aaron Elson: Would Frank come to the reunions?

Eleanor Mazure: No, he never came. He just, I can=t tell you, I don=t know. It=s just Clark that got interested in history, and that=s it. He just sticks with it.

Aaron Elson: About what year was it, it was the year after he passed away that you first came?

Eleanor Mazure: The first year I came was Rockford. But Clark came a year previous to that, which was a small reunion, I think the Service Company had it, it was in Detroit, Dearborn or Detroit, and the reason we found out about it was, Clark was always connecting himself with his veterans at his work, he worked for Caterpiller, and the one man was a World War II veteran, so Clark would every opportunity he would get he would talk to, so one day this man gave him one of the magazines, I don=t know if it was VFW or American Legion, and the 712th was listed in there that they were gonna have a reunion, so that was this little mini-reunion up in Michigan. So he went to that, and then the next year was Rockford, and he said, AMa, you have to come to that.@And I said, AWell, you know, I don=t know if I=m going to know anybody there anymore.@He said, AWell, you=re gonna come anyway.@And he had been corresponding with Ray Griffin also, putting the pieces together, so I went, and I=ve been coming ever since. Because I remembered a lot of the people there.

Aaron Elson: And you save up all year for this trip?

Eleanor Mazure: Well, you know, you manage, this is my highlight of the year. I don=t go on other vacations anymore. I used to, you know, when our kids were small, we used to go, but this is my highlight of the year.

Aaron Elson: And where do you live now?

Eleanor Mazure: I live in, well, it=s like a suburb of Cleveland, Aurora, Ohio, which is where Sea World of Ohio is, and I have three brothers and they=re all single, none of them got married, so they bought a home and made a home for my parents. And then I moved out that way and I lived out of Cleveland for about, oh, I don=t know, ten or more years maybe, and then I moved back in, because I was driving to work from 40 miles a day one way. But you have to drive where your work is. You can=t always live on top of your work.

Aaron Elson: And what kind of work did you do?

Eleanor Mazure: I worked in a hospital for 28 years. I did various things, I worked in admitting, I have a lot of volunteer hours in, because I like people, I like helping people, that=s part of my makeup. And then I ended up, and I was a cashier, but I ended up being a claims person, claims processor they called it, and I=ve been doing all of the insurances but plus, I=m an expert Medicare biller, because I started to do Medicare, which I didn=t want to take but the boss said, AEleanor, you have to try it for two weeks,@ nobody else wanted the job. So they put me in it, and said ATwo weeks,@ and it ended up being like 18 years or something.

Aaron Elson: So that must have been when Medicare was first ...

Eleanor Mazure: The first day it was initiated they put me on it, and there wasn=t anyone at all to teach us, we had nothing, we had nothing. No one knew anything about it, the government just initiated it, and you had to pick it up on your own. And I did. And I didn=t mind it, I loved it, because basically I=m a hard worker.

End of side 1

Side 2

Ed Stuever: On Tennessee Maneuvers, when my son was born, they were looking for me for two weeks at least. You know, Jen would almost write to me every day, and then when there was mail, the guy that called off the mail, he'd hand a letter to this guy and then he'd hand one to that guy, then Jen always had her lipstick on the back end, and everybody would take a kiss on it before I got it.I'd always have Jen send me the hard salami, and I'd take a real sharp knife and I'd cut it in real thin pieces so everybody'd get some.

Eleanor Mazure: I used to send that. I'd seal it in paraffin, and then I would put it in some kind of a container that didn't break, like maybe a coffee can. And it never spoiled, but it took many, many weeks.

Aaron Elson: Did you save your letters?

Ed Stuever: I've got a box full in my attic.

Eleanor Mazure: I don't have any because I had a robbery in my house. I had a whole footlocker full, I saved every solitary one. Do you have a copy of that Christmas card that you fellows sent us from overseas, and it said "When the lights go on again all over the world." And it had two plugs, electric plugs, and they were ready to go together. It had different significant meanings to it.

Ed Stuever: What they meant was peace. Lights go on again all over the world was a famous song in those days. And don't sit under the apple tree with anyone else but me. In Normandy we had nothing but apple trees. There was a lot of heartbreaking songs in those days.

Ed Stuever: the knob on top came loose, and I soddered that back on there, and I made a crystal out of celluloid cover, and it went through Tennessee maneuvers, and all through the war, and every night the guys would use it on guard duty. Whenever there was a flash of gun. And I'd never see that watch for weeks. And finally when the battalion got together, or our company got together, we're sitting under an apple tree, and finally it dawned on me. "Is my watch still around?""What do you mean your watch?" I was offered twenty dollars for it. What do you want to pay me twenty dollars for, I only paid a dollar for it. Oh, it's history. So I've still got it. It'll run for a little bit, but the springs all...

- - -

Published on November 20, 2016 16:25

October 14, 2016

The Wall (no, not THAT wall, this post is apolitical)

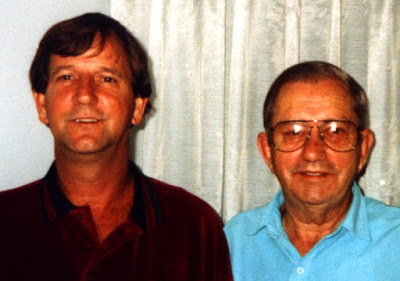

Doug Coleman (Vietnam) and his father, Cleo Coleman (World War II) Just a side note, the title of this post has nothing to do with the presidential race. Rather it is about the wall that sometimes exists between a father and a son, that did exist between my father and me. I learned many years after his death that when I ran away from home at the age of six (I only made it as far as the corner grocery store, where I unraveled my hobo stick and spent my life savings on a Pepsi before my grandmother came looking for me and brought me home), he discussed getting some kind of counseling for me, and even though I never got the counseling, I realized only then that he was more sensitive than I knew him to be growing up.

Doug Coleman (Vietnam) and his father, Cleo Coleman (World War II) Just a side note, the title of this post has nothing to do with the presidential race. Rather it is about the wall that sometimes exists between a father and a son, that did exist between my father and me. I learned many years after his death that when I ran away from home at the age of six (I only made it as far as the corner grocery store, where I unraveled my hobo stick and spent my life savings on a Pepsi before my grandmother came looking for me and brought me home), he discussed getting some kind of counseling for me, and even though I never got the counseling, I realized only then that he was more sensitive than I knew him to be growing up.When I got my deferment from the Vietnam War, he said he opposed the war on strategic grounds -- that was circa 1970 -- because he didn't think it was winnable, but then he had second thoughts and hinted that he thought the Army might have made more of a man out of me.

I never knew him very well, and that's something I regret. We never bonded the way fathers and sons often do. His father was an excellent chess player and so was he, but I could never get him to play chess with me and soon lost interest in the game. We never went to a baseball game. In retrospect, I remember him once saying that he wished he could have gone out for a beer with his father-in-law, my maternal grandfather. I never went out for a beer with my father. But before I start crying in my nonexistent beer, I used to say the only thing I inherited from my father was his sense of humor -- he had a great sense of humor and was a wonderful storyteller when I was a child -- and for that I'm eternally grateful.

Now, getting back to this post before I get any more maudlin, it is about fathers and sons. A few years back I read online that a book was coming out that was an oral history of fathers who served in World War II and their sons who were in Vietnam. I thought damn, that's a good idea, and in fact it's an idea I had at a reunion of my father's 712th Tank Battalion when I learned that Cleo Coleman, a B Company veteran from Phelps, Kentucky, had brought several family members to the reunion including his son Doug, who was a veteran of the Vietnam War. I thought I'll bet they never sat down and compared wars, and it turned out I was right, so I got them to sit down together with the tape recorder running. Dale Albee, another World War II veteran, joined us. Dale was mostly quiet, listening, during the interview, but when the subject of movies came up, Dale, the World War II veteran, remarked that one of the most realistic scenes he ever saw in a movie was in "Platoon," Oliver Stone's movie about Vietnam, when a Vietcong soldier is shot and a puff of dirt comes out of the back of his jacket. Doug said he saw that too, and that's what it was really like.

I didn't buy the book about fathers and sons, "Brave Men, Gentle Heroes," when it came out. But a couple of months ago I saw a notice that the author, Michael Takiff, was going to speak at the New Britain Museum of American Art. As I work part time in New Britain and occasionally stay there, I thought I'd like to go hear him talk, even if it meant I'd probably have to buy his book.

Not that I didn't want to buy his book. As an author, I love selling books and collecting the occasional royalty, but as a reader I hate paying full price for a book, especially when I'm not likely to read it and I could buy it used for a few cents plus $3.99 shipping, and in many cases used on amazon means practically new.

The talk was interesting. Virtually everything he said about the World War II veterans I had heard a dozen times over straight from the source, albeit from different veterans, and the audience was very moved. Afterward I bought his book, paperback, for $15 and he signed it, but I still haven't read it. But I asked him a question at the end of his talk.

The whole 45 minutes that he spoke, there was no humor. The few Vietnam veterans I've spoken with at length often mentioned humor, and humor was essential to both Vietnam and World War II veterans. Look at all the humorous blogs like "Duffel Blog" from Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, and all the funny videos of terrorists accidentally blowing themselves up. And the introduction of the talk noted that the author, Takiff, was a comedian early in his career. So I asked him if he had heard any humorous stories from the veterans of either war. He said he couldn't think of any offhand.

Of the 20 reviews his book got on amazon.com, most are of the five-star variety, but the one two-star review he got pointed out how all the stories in the book are grim. Reading that, I didn't regret not yet having read the book.

On the other hand, there isn't much, if any, humor in my interview with Cleo and Doug Coleman. The interview is 29 pages single spaced. I just did searches on the words "laugh," "funny" and "humor" and the only thing that came up was a comment in which Doug was talking about his life after the war:

And here's the part about "Platoon":

Doug Coleman: I=ll tell you, the life I live right now, believe it or not, and he can tell you that, I mean I laugh and joke about it, and my wife laughs and jokes about it, my kids even laugh and joke about it, and you might think it=s dumb and stupid, and he can tell you, I live that kind of life, I live like Forrest Gump, don=t I? I mow grass for how many hours, I live out in the country, I don=t hardly never see nobody, and that=s the way I live.

Cleo Coleman: Just like me, I want to be by myself a lot of times. I just don=t know, if the war did anything to me or what.

The full interview with Cleo and Doug Coleman is at tankbooks.com. It is also included in my collection of a dozen fascinating edited transcripts, "A Mile in Their Shoes: Conversations With Veterans of World War II."

Doug Coleman: I seen things in movies that I relate to...

Aaron Elson: Because movies, they go for the grotesque and the really bizarre, do the things that they show in movies about Vietnam, do they approximate what you saw yourself?

Doug Coleman: Yeah, a lot of it is, it=s just like the guy that made Platoon, that=s the way I lived. The guy that made the movie, he was there. He lived that life. Now that=s exactly almost identical to the way, I know this was a movie, but that=s the way I lived. And that=s how it was.

Dale Albee: May I say something? The same thing I was gonna say of APlatoon.@ Do you remember when that Vietnamese ran, and the guy shot him, did you see that puff of dirt come out of his back?

Aaron Elson: I don=t remember, but yes...

Dale Albee: Did you remember that? He shot him, and you saw that puff of dirt.

Doug Coleman: Yeah.

Dale Albee: That=s exactly what you get when you hit a guy. When you see a guy running and you shoot him that=s exactly what you get is that little puff. And that was one of the things that I remember about APlatoon.@ Because that=s actually the way it happened.

Published on October 14, 2016 09:01

July 25, 2016

Man Overboard: The Sequel

Lou Putnoky

Lou PutnokyLou Putnoky called me on Saturday afternoon. Lou is 92 years old, maybe 91. A Coast Guard veteran of World War II, he was a radio operator on the USS Bayfield, the flagship of the Utah Beach invasion fleet. He is not in the best of health, having had at least two serious heart attacks, and is living with his daughter since his wife passed away a few years ago.

Lou gets sentimental, or nostalgic, and calls me from time to time. We have this routine, somewhere between Abbott and Costello and Hillary and Donald. He thanks me profusely for all I've done to preserve veterans' stories, and I remind him that all I've done is flip the switch on a tape recorder, and there would be nothing to preserve if it weren't for veterans like himself. Nothing will ever convince him that I'm not one of the greatest contributors to preserving the history of World War II, and nothing will ever convince me that he isn't one of the greatest storytellers to come out of the war, although his voice these days is not as strong and compelling as it used to be.

In 1994 I wrote to Stephen Ambrose and asked if he could provide me with the names of any D-Day veterans living in New Jersey that I could interview for a special section the newspaper I worked for was planning to do in conjunction with the 50th anniversary. He sent me a list, but Lou's name wasn't on it. One of the men on the list, Dr. Vincent del Guidice, who had been a pharmacist's mate on the USS Bayfield, suggested that if I wanted stories I should call his old shipmate Lou.

Which I did. Lou's wife, Olga, answered the phone and I told her I'd like to interview her husband about his experiences on D-Day. Before she called Lou to the phone, she said I should make sure to ask him about one particular story, because it was one he almost never talked about.

That story is included in my book "A Mile in Their Shoes" and in my audiobook "The D-Day Tapes," but here it is in Lou's own words, if you don't mind listening to an audio file of it. This is an audiobook blog, after all.

Man Overboard

That was recorded in 1992. Lou went on to tell many other stories in that three-hour interview and we've kept in touch over the years. I was able to bring him to an event at the Yogi Berra Museum one day so he could get his picture taken with Yogi, with whom he served on the Bayfield. In that very first interview he made excuses for Berra never attending a Bayfield reunion, Yogi was busy with other obligations and all that. At the time I had no idea how much it would have meant to the veterans if Yogi had made an appearance at a reunion.

Usually Lou calls on days of significance to veterans, like Memorial Day or Veterans Day, or the anniversary of D-Day, when he gets especially sentimental. So I wasn't expecting him to call this weekend, but I was glad I was at home. Sometimes he leaves rambling, sentimental messages on my answering machine.

His voice was weak, and he said there was a second part to the story about the "man overboard," which was the title I gave to his interview in "A Mile in Their Shoes." Then he told me the story. When he finished, I put my phone on speaker, flicked the "on" switch of my digital voice recorder, and made him tell me the story again.

Following is a transcript. There were a couple of places where I couldn't make out a word, so bear with me if something doesn't quite make sense.

"

Aaron, I called you just to thank you for your articles about all the fine servicemen that you've written about, and the one that you wrote me about was the Duffy situation where he fell off the battleship Nevada and we helped search for him but we couldn't find him. So then I reported back to our flagship, and they're all waiting for us, they thought that we'd got in serious trouble.

"No," I says, "we were delayed because the Nevada had a man overboard and they wanted us to make two turns around the ship and said sorry, we couldn't find him, and we dashed back here because we were late." And what happened, as I was talking to the officers, I see a radio man, a friend of mine, about 15 or 20 feet away. I say "Sparks, the next time you talk to the Nevada, ask them who it is and where he's from." And everybody looked at me real crazy, and then I even felt embarrassed. And what happened was, I was just so embarrassed about it, with all the shooting going on I says how in the hell can I ask, it seemed like a stupid question.

What happened was, after I don't know how many weeks later, when we were out in the Pacific, Sparks -- wait, [I'm getting ahead of myself]. That evening, Sparks was eating, and he says, "Hey, Lou, the Nevada called and I was talking to them and I asked them where the guy was from that went overboard and they couldn't find him. And they told me he's from New Jersey. A town by the name of Carteret. And his name was John Duffy." And I said, "Oh, my god, I went to grade school with him," and I said "I know his parents." And we made the sign of the cross, and we said a little prayer, a silent prayer between us. And we continued to eat, but both of our eyes welled up a little bit." But it's, that happens.

And then so many weeks later, I find out that, as we were coming back from chow we were going out to the Pacific to invade Iwo Jima, and I was coming back from chow and I looked ahead of me and it was about 5 o'clock in the evening, and I see Sparks going, and I just wanted to talk to him again, so I had a little bit of a problem trying to catch up to him, and finally I got to the end of the corridor and I opened the hatch, and there's a good 50-foot opening over the Number 3 hold before you come to the aft five-inch gun, and all of a sudden, nobody's out there. Sparks disappeared. And I looked. I looked. And I don't know what, something made me, believe me, it had to be the man upstairs, He says take a fast look, and I looked, the deck was wet, and there's a section where there's no lip, the side of the ship where we lower the ship's crew and the cargo nets, and I saw a little bit of a skid mark. I said that skid mark, it had to be Sparks' shoes as he slid right through there when the ship rolled to the opposite side, and I yelled "Man overboard! Man overboard!" Because I was convinced, I didn't see him fall overboard but I was convinced he went overboard, because he couldn't have disappeared any other way because believe me, I knew every inch of that ship. And then I ran back to the after lookout and I told him, "Report to the bridge man overboard." We were doing 23 knots, we were trying to outrun, we could outrun a sub at 23 knots so that's what we were doing. It took a few minutes and I ran back to the after room where we have all the garbage for the day and four guys were standing there shooting the bull, and I says, "Give me a hand, we have a man overboard, I've got word from the OD [officer of the day], I lied, I could have got in serious trouble, but the good Lord told me I should do this. I said, "Throw all the garbage overboard," because I wanted, if they did send a boat out, they could follow the garbage trail and verify the position, that they're close by. And sure enough, we did find him, and Sparks told me afterwards when I spoke to him, and I never told him, I never used the term "I saved your life," I was just glad to see him. And he was glad to see me. I could have gotten in serious trouble but I didn't care. I said, "Somebody up there wanted you to live. So I don't know how good a family you have but let me tell you the good Lord was on your side." Make sure that you find a wife and have children because He went way out of his way to get you," and I remember him telling me that was the first time he really was convinced that the Earth is round because when he fell, he saw our ship just disappear, and that ship is 40 feet above his head. "And as I was in the water I saw the ship just going down, I saw the name of the ship, USS Bayfield, PA33, and just going down as if it was sinking, going right over the horizon. I just can't get over that."

And now all of a sudden, we never directly approached each other to say, our paths didn't, we just didn't run into each other aboard ship we were so busy fighting the damn war, we forgot to thank each other. I wanted to thank him just for being there and making me feel good whenever I felt, God came down and said I helped save this man's life. And it's a grand feeling. All I know is by his nickname Sparks. I don't know his real name. Maybe somebody will read it in a book and they'll be able to get in touch with me."

Lou Putnoky in 1992

Lou Putnoky in 1992

A Mile in Their Shoes at Amazon.com

The D-Day Tapes on eBay

Lou and Yogi Berra

Lou and Yogi Berra

Published on July 25, 2016 07:04

July 17, 2016

A gem of an interview from 2004

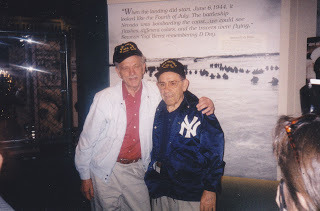

Eugene Sand, left, and Edward "Smoky" Stuever

Eugene Sand, left, and Edward "Smoky" StueverOver the years, as I attended reunions of my father's tank battalion from World War II, there were several veterans I would see almost every year. As a result, I interviewed some of them on several different occasions, sometimes recording a casual conversation in the hospitality room with other veterans at the table, at other times doing a longer, one-on-one interview. As a result, I would sometimes have several different taped versions of the same story, each time with a few more details, or, frustratingly, a few details that differed from the time the same veteran told the same story two years earlier, sort of a one-man version of "Rashomon." Once, for example, I was listening in as Jim Flowers told the story of Hill 122 to a youngster who came to the reunion with his grandfather. I had heard Jim tell the story dozens of times, but as he grew older, he would sometimes have to reach for a detail, which would result in a lengthy pause. At one such pause I provided the detail, which prompted Jim to admonish me by saying "Who's telling this story, me or you?"

There was one veteran, Ed "Smoky" Stuever, who had so many stories, about growing up in the Depression as the son of two hearing-impaired parents, about helping to build the Skokie Lagoons with the Civilian Conservation Corps, about having his tonsils removed, about life in the horse cavalry, about repairing and changing engines on tanks, about the death of his buddy Marion "Shorty" Kubeczko, that I resolved to sit him down and get his story from start to finish, which I finally did in 2005, when he was 88 years old. One of my earliest recordings, going back to 1991 or '92, was his account of how he got the nickname "Smoky." He was in the veterinary detachment of the 11th Horse Cavalry in California in 1941. His lieutenant's wife gave birth one night so the lieutenant passed out cigars in the morning, and the men sat around smoking their cigars before they began working on the horses. There was one horse which nobody wanted to deal with because it had a reputation for meanness, but it had a "stub" -- I believe he meant a thorn -- in its hoof, and somebody had to take it out. So Ed said he would take it out. He then said, "Watch my smoke."

He had the horse's leg cradled in his crotch and was about to remove the thorn when the horse suddenly lay down, causing Ed to turn his head. He still had the cigar in his mouth and the horse's side made contact with the lit end of the cigar. "Watch my smoke," Ed repeated at that reunion. "There goes Smokeeeey!" as the horse sent him flying into several bales of hay.

It was only after I'd heard that story many times that Ed remarked that he never liked the nickname, even though at every reunion all the other veterans would still call him Smoky.

That 2005 recording was one of the highlights of my so-called career as an oral historian. Ed filled two 90-minute cassettes, then we broke for a battalion luncheon, and when we returned he filled another 90-minute tape. After digitizing and transcribing it, I realized there were several stories he didn't even cover, but that I had on earlier tapes.

My New Year's resolution this year was to go through my old tapes and digitize some of the ones that I'd overlooked over the years. I digitized and transcribed two interviews -- with Bob Hagerty and Morse Johnson of A Company -- in January and here it is the middle of July, but this month I got back to keeping that resolution, and just the other day I discovered a hidden gem among my 600 hours of interviews.

I didn't realize, or had completely forgotten, that the year before that 2005 session with Ed Stuever, I had interviewed him at the 2004 reunion. His daughter, Rita Cascio, was with him and she helped with the interview by asking him to provide some details which he might have overlooked.

Ed Stuever passed away in September of 2014. He was 97 years old.

Following is the audio of that 2004 interview. The full three-hour 2005 interview is available in my collection of "More Tanker Tapes," in my eBay store.

Track 1Track 2Track 3Track 4Track 5Track 6Track 7Track 8Track 9Track 10Track 11Track 12Track 13

Purchase "More Tanker Tapes," which includes the three-hour 2005 interview with Ed Stuever, in my eBay store.

Thank you!

(Ed Stuever passed away in September of 2014. He was 96 years old.)

Edward H. Stuever beloved husband of the late Genevieve (nee Schmitt); devoted father of Tom, Mary, Rita Cascio, Therese, and Lora (Steve) Hall; dear grandfather of 10; great-grandfather of 15; great-great-grandfather of four. Edward was a US Army veteran of World War II and the founder of Stuever & Sons Draft Beer System. Funeral Monday, 11 a.m. from Salerno's Rosedale Chapels, 450 W. Lake St. (¾ mile west of Bloomingdale/Roselle Road), Roselle, to St. Matthew Church, Glendale Heights, for Mass at 12 noon. Interment Elm Lawn Cemetery. Visitation Sunday, 3 to 9 p.m. at the funeral home. Please omit flowers. For information, 630-889-1700. Published in Chicago Suburban Daily Herald on Sept. 6, 2014 - See more at: http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/dail...

Published on July 17, 2016 06:55

May 27, 2016

Memorial Day 2016: Ed Hamilton and the Battle of St. Pierre Mont

Jim Flowers, 712th Tank Bn., left, and Ed Hamilton, 90th Infantry Division.

Jim Flowers, 712th Tank Bn., left, and Ed Hamilton, 90th Infantry Division.The most impressive orator and one of the most remarkable veterans I've met was the late Colonel Ed Hamilton, who was a fixture at 90th Infantry Division and 712th Tank Battalion reunions, even though he was an infantry officer (and a graduate of West Point at that) and not a tanker, but he and Lt. Jim Flowers of the 712th developed a bond that grew over the years. While searching through some old files in my "deep computer" -- hey, if the Internet can have a deep Internet, I can have a deep computer, can't I? These were files in a folder marked "system recovery" and then c drive, users, aaron and desktop, but they're not on my desktop, only on the desktop in the recovered files folder -- at any rate, I already forget what I was looking for in the first place, but I found a file called "The Battle of St. Pierre Mont" by Col. Edward Hamilton. I'm not sure where it came from, but I think someone in his family might have sent it to me after his death in 2006. His obituary in the Washington Post is on the Internet, so I'll post that before Ed's description of the battle. Decorated Veteran Edward Smith Hamilton

By Matt SchudelWashington Post Staff Writer

Tuesday, July 4, 2006 Edward Smith Hamilton, 89, a highly decorated combat veteran of World War II who later embarked on clandestine buccaneering adventures along the coast of China during the Korean War, died of pneumonia June 30 at his home in Annandale. Mr. Hamilton, a 1939 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, was commander of an Army infantry battalion that went ashore at Normandy Beach on June 8, 1944, two days after D-Day. His unit of the 90th Infantry Division saw considerable action throughout the summer on its march through France. For his coordination of the defense of a key bridge in France on Aug. 5, 1944, Mr. Hamilton was awarded the Silver Star. A month later, on Sept. 8, he led a surprise raid on German positions at Avril, France, that disabled four tanks and led to the capture of 17 enemy soldiers. For his daring assault and his heroism under fire during the battle, Mr. Hamilton received the Distinguished Service Cross, the Army's second-highest commendation for valor. Two days later, he was wounded in battle and lost his left eye. He was given a battlefield promotion to lieutenant colonel and received, among other decorations, the Bronze Star and three awards of the Purple Heart. After recuperating, Mr. Hamilton returned to his hometown of Dallas, Ore., in 1946 to open an insurance agency. In 1950, as the Korean War was heating up, he was lured back into action as a CIA agent in Taiwan, working with the Chinese nationalist forces of Chiang Kai-shek. Nicknamed the "One-Eyed Dragon," Mr. Hamilton led combined American and Chinese guerrilla units in clandestine attacks against communist forces on the Chinese mainland. His role in the covert actions conducted along the southeastern coastline of China is detailed in the book "Raiders of the China Coast" by Frank Holober. Mr. Hamilton was in Taiwan from 1950 to 1954 before he was transferred to Washington. In 1956, he was sent to Germany as an undercover agent working in counterintelligence in East Germany and Turkey. He left the CIA in 1959 and took a position as operations officer with the old Civil Defense Administration. He retired in 1973 The Battle of St. Pierre MontBy Edward S. Hamilton

On 6 Sept. 1944 the 357th Infantry of the 90th Infantry Division moved from the vicinity of Vitry les Rheims to the vicinity of Anoux. My Battalion, the 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry, was ordered to secure the Eastern approaches to the Regiment. I did so with outposts. Early on the 7th I was ordered to report to the Regimental Commander, Colonel George B. Barth. I knew this had to be a move and it wasn't going to be West. I went ahead and ordered the Battalion to break position and assemble in march formation. Company B to be the Advance Guard. All this was being done while I was en route and at Regimental Headquarters. Now, I wasn't certain there would be a move and I surely did not know, if so, that the Regimental C.O. would place my Battalion in the van. But if there was and he had another Battalion in mind I had a good position from which to make a case. At Col. Barth's meeting I mentioned an article by then Lt. Col. Manton S. Eddy which was either in the Infantry Journal or another publication in which he related a WWI combat experience where a German unit was marching in column from one ridge to the next coming in sight of a U.S. Army Artillery observer who took it under fire, annihilating it. Col. Eddy called it an artilleryman's dream. We were in that same type of terrain which prompted me to hold the Battalion's advance from one crest to the next until the Advance Guard attained that crest. Col. Barth's order placed my Battalion in the Advance Guard, assigning me a Zone of Advance that included St. Pierre Mont, Neufchef, Hayange and on to the Moselle River. Leaving the Command post, I got on the radio and ordered my Executive Officer to head East. The Battalion was under way before I returned. Our route of advance followed a road that took us East but at a point due West of St. Pierre Mont the road obviously continued NE toward Trieux. I ordered Capt. Burrows G. Stevens, B Company Commander, to depart the road, move cross country through a wooded area and seize St. Pierre Mont, concurrently outposting the ridge immediately to the North. The remainder of the Battalion was to follow in trace. In an advance my modus operandi was to follow in rear of the lead company. B Company seized its objectives. The next element in the column was the Battalion Anti-tank Platoon. Emerging from the woods, it came under mortar fire, hesitating with vehicles and men fanning out at interval. I ordered this platoon in emphatic terms to move rapidly onto St. Pierre Mont and assume firing positions. As B Company was deploying it came under fire from a German artillery piece located approximately 1,000 yards to the SSE. This was direct fire with the flash of the muzzle blast looking right at you. I ordered up a section of two heavy machine guns to engage the cannon. The German crew had little stomach for this duel, quickly limbering up and disappearing into the forest. Sgt. Warren Wightman, leader of the outpost squad, deployed his men along a shallow brush line that ran west to east along the crest of the ridge. He sent his Assistant Squad Leader, Sgt. Alva Lumpkin, with another man on patrol toward a farmhouse to the NW. Lumpkin reported back sighting a German Platoon in the area. That Platoon launched an assault that carried all the way to the crest with the German Commander killed crashing through the brush line. I witnessed that action. From the distance it appeared to me that he was shot in the air. Alva Lumpkin remembers it vividly. He never contemplated becoming so close and intimately acquainted with a German Officer. The Lieutenant landed on him. We captured a German ambulance that unaware of our presence was headed North on the road from Avril. I ordered A Company to establish a position in the woods across the highway to the East of St. Pierre. Surprise is one of the Principles of War and I did not want a German force moving into my front yard concealed by the forest. That night the Germans launched a mechanized attack or probe against St. Pierre from East Northeast which was repulsed, leaving one mechanized carrier disabled. At around 0200 in the morning I heard heavy traffic to the NE on the road between Fontoy and Trieux located to our North. I got Lt. Joseph McDonald, my Artillery Liaison Officer, from the 343 Field Artillery Battalion, who had scaled the medieval colombier for an Observation Post to lay interdiction fire on this highway. Any effect? We could not tell. The morning of 8 September I was ordered to continue the advance. I placed A Company in the Advance Guard and entered the woods on an unimproved road at a point where the German Artillery piece was located the previous day. I moved up along the column and for a short time walked with the point squad. I would probably flunk tactics 101 for that. But sometimes considerations of leadership take precedence. After the Battalion had been moving through the woods for about an hour, I received an order to counter-march and reoccupy my previous positions. On attaining the western edge of the woods I observed German artillery fire falling on these positions. Sensing I would sustain undue casualties in this course of action, I requested permission from the Regimental Commander to occupy positions on Hill 313 immediately South of St. Pierre Mont. Ten meters higher elevation than St. Pierre Mont, the terrain was shaped like a reversed L with the shorter leg parallel to the woods where I was standing. Col. Barth granted permission. I ordered C and A companies onto the forward slope, C Company on the West and A Company on the East, B Company in Reserve on the reverse slope. The Battalion was now deployed facing North with A Company's right flank refused, resting on the shorter leg of the L facing the woods. The Battalion was commencing to dig in when lo and bohold, the Germans launched a coordinated Armored-Infantry attack in a West-Southwest direction. They were unaware of our movement and disposition. Launched against phantom positions, the German line and the sides of the tanks were exposed to enfilade fire from the Battalion machine guns, mortars and anti-tank guns. Those anti-tank guns were in crest defilade when the attack began and had to be mucked forward to the crest, where they opened fire. I saw one round blow the turret off a Mark IV tank. Lt. McDonald brought the artillery into the shoot. All combined with devastating effect. Lieutenant McDonald was on the Wastern crest of Hill 313 sensing and ranging the shift of German Artillery in order to bring down his counter battery fire. He was hit by an incoming round. As I was in the center of our line at the time I did not see him fall. But as I moved to the Wastern end of the line shortly later I saw a stretcher with the familiar reddish hair. It was McDonald, pale and motionless. I ordered the litter bearers to get him to the aid station as quickly as possible. It was too late. His counter-battery fire was apparently effective, for the German fire ceased. The gallant Red Head had fired his last round. The attacking force of the 106th Panzer Brigade was utterly destroyed. A wounded German Officer who had fought at Caen stated, "St. Pierre Mont on 8 September was far worse than Caen." There were 17 wounded Germans in the farmhouse on St. Pierre Mont belonging to M. Joseph Mayer. The Battalion remained in place the night of 8 September and resumed the advance the following morning. Before leaving St. Pierre Mont let us consider several features of the battle. It is often the actions of a small unit or a single man that not only influences the immediate outcome of a battle, but also the subsequent course of events. It is very easy to hypothesize such in this situation. Loss of the North ridge held by the outpost would have awarded the Germans with a fire base, the likelihood of its reinforcement, a fight to hold St. Pierre Mont, and/or to dislodge them. Such a course may also have eliminated the movement and surprise of 8 September, all costing American blood and life. I visited the outpost area later in the day. I gazed at the German Lieutenant lying supine. He was a handsome lad, blond with fine features. I wondered if he had already entered and was feasting in Valhalla, that legendary palace of heroic souls. Whatever else, he was a brave soldier. Already his boots had been removed. Perhaps, by the farmer from the house to the North-Northwest. In front of the outpost position lay the German platoon fanned out in varous positions of mortality, some clutching the German "potato masher" grenades, some supine, others contorted. After being contacted by Alva Lumpkin in 1997 I wrote a citation recommending Sgt. Warren Wightman for the Silver Star which was awarded in March. Alva is a very interesting man. Before returning to the States he went through an officers training course and was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant. Of course the German Lieutenant is firmly imprinted on his mind. He later became a trial lawyer in his home state of South Carolina. His father, Alva Lumpkin Sr., a United States Senator, was appointed to fill the term of Jimmy Byrnes, appointed Secretary of State by President Truman. Senator Lumpkin served from July 18, 1941 until dying in Washington, D.C., on August 11, 1941, perhaps the shortest tenure of any U.S. Senator in history. Alva's paternal grandfather, William W. Lumpkin, enlisted in the Confederate Army at age 15, serving briefly before the end. His great-great uncle, Colonel Samuel Pitman Lumpkin, subject of one of the Washington Times' great continuing Saturday series of the Civil War, who was also an MD, commanded the 44th Georgia Infantry and died of wounds sustained at the battle of Gettysburg. His maternal great-grandfather, John Waties, wounded at the Battle of Franklin, was a Captain in Brig. Gen. William H. Jackson's Confederate Cavalry. His great-great-great grandfather, Thomas Waties, a student at the U. of Pennsylvania, roomed with Temple Franklin, both of them residing with Temple's grandfather, Benjamin Franklin, at the beginning of the Revolution, before the Franklins departed for France. Waties was subsequently captured on the high seas, confined in England, escaped to France, and returned to America where he fought with Gen. Francis Marion, the "Swamp Fox." Alva has written a biography of his Revolutionary Grandfather, Judge Thomas Waties. St. Pierre Mont is a long way and a long time from the swamps of South Carolina. Wedding cake and cordite don't mix. Joseph Mayer, whose farmhouse on St. Pierre Mont was in the vortex of battle, was scheduled to be married on 7 June. "The best laid plans of mouse and man oft gang agley." The only American soldier killed in the two-day battle was Lt. Joseph McDonald. I went to the Battalion Aid Station the morning of the 9th to pay my respects. He still lay in endless sleep on the stretcher. It was a grievous loss. He rests today near his hometown of Brownstown, Illinois.

"With a cheery smile and a wave of the handHe took his leave for another land.Yet you cannot say, you must not sayThat he is gone for he is just away."

Edward S. Hamilton

Lt. Col. U.S. Army (ret)C.O. 1st Battalion, 357th Infantry90th Infantry Division, World War II

Ed Hamilton (family photo)

Ed Hamilton (family photo)

Published on May 27, 2016 05:57

May 8, 2016

A new sampler from Oral History Audiobooks

Most of the Oral History Audiobooks in this collection are available in my eBay store. Here is a new audio sampler with a bit of a description for each track.

Track 1: Jerry Rutigliano

In 1994 when I interviewed a series of D-Day veterans in conjunction with the 50th anniversary of D-Day, I wanted to find a veteran who suffered from post traumatic stress disorder. So I called a psychologist at the VA Hospital in Orange, N.J., and asked if he could suggest a patient to interview. He set up a meeting with Jerry Rutigliano, a former prisoner of war. This particular story, in which Jerry showed me a photo of him sitting with Jimmy Doolittle, always gets me a little choked up. A waist gunner on a B-17, Jerry was shot down on his sixth mission to Berlin. It was his 27th mission overall, and General Doolittle had recently raised the number of missions for crew members from 25 to 30. Jerry met General Doolittle at a reunion in the 1970s. Excerpts from my interview with Jerry are available on my double CD World War II Bailout Package, available in my eBay store and at oralhistorystore.com

Track 2: Karnig Thomasian

Karnig Thomasian was a gunner in a B-29 that was destroyed when two bombs of unequal weight collided in midair. For the next several months he was a prisoner of the Japanese in Rangoon, during which time he was regularly beaten and starved. In this excerpt, he describes the emotional rollercoaster of coming home as the plane dipped down and flew past the Statue of Liberty. Karnig's full two-hour interview is included in the collection "POW: Right in the Keister," available in my eBay store.

Track 3: Erlyn Jensen

Erlyn Jensen is the sister of Major Don McCoy, the B-24 command pilot who was killed leading the ill-fated Kassel Mission of Sept. 27, 1944. In this brief excerpt, Erlyn tells how her mother blamed her son's death on President Roosevelt. Erlyn's interview is included in "The Kassel Mission: An Oral History Epic," available in my eBay store.

Track 4: Don Knapp

Don Knapp was a tank commander in the 712th Tank Battalion, my father's outfit, which is what got me started doing this whole oral history thing. In this excerpt, Don talks about his role in the fight that broke out in the middle of the night of Sept. 8, 1944, between the 712th Tank Battalion and the 108th Panzer Brigade. Don's full two-hour interview is included in both The Tanker Tapes, available in my eBay store and at oralhistorystore.com, and "The Middle of Hell: An Oral History Epic," about the role of the battalion's First Platoon, Company C in the battle for Hill 122 in Normandy. "The Middle of Hell" is available in my eBay store.

Track 5: George Bussell

George Bussell was a tank driver in Company A of the 712th Tank Battalion, and one of the most colorful characters you're ever going to meet through an oral history audiobook. In this excerpt he also talks about the battle with the 108th Panzer Brigade. George's full-length interview is included in "The Tanker Tapes," available in my eBay store and at oralhistorystore.com.

Track 6: Erlyn Jensen

In this excerpt, Erlyn Jensen described the day in 1943 that her brother came home on leave before going overseas. A transcript of my interview with Erlyn and a great deal more about this epic battle between 35 B-24 Liberators and 150 Fokke-Wulf 190s and Messerschmitt 109s can be found at www.kasselmission.com, and while you're at it, why not think about joining the Kassel Mission Historical Society.

Track 7: Ed Boccafogli

Ed Boccafogli was a paratrooper in the 82nd Airborne Division and fought in Normandy, Holland and the Battle of the Bulge. After you listen to this (not before), read this story about Johnny Daum as told by his nephew. My full two-hour interview with Ed Boccafogli is included in "The D-Day Tapes," available in my eBay store and at oralhistorystore.com.

Track 8: Henry Dobek

Henry Dobek was a navigator on a B-24 on the Kassel Mission of Sept. 27, 1944. His plane, piloted by Paul Swofford, was one of only four of the 35 planes in the 445th Bomb Group to make it back to their base at Tibenham, England, that day. Of the others, 25 were shot down, three crash-landed in Allied territory, two reached an emergency landing field in England, and one overshot the runway at Tibenham and crash-landed five miles away. For the full story, visit www.kasselmission.com. "The Kassel Mission: An Oral History Epic," is available in my eBay store.

Track 9: Bill Scheiterle

Bill Scheiterle was a lieutenant, and later a captain, in the Marines. In this excerpt, he describes an incident on the island of Peleliu. My full interview with Bill is included in "Four Marines," available in my eBay store, and the printed transcript is included in my book "Semper Four," along with transcripts of my interviews with three other Marines, available in my eBay store.

Track 10: Stanley Klapkowski

Stanley Klapkowski was a gunner in C Company of the 712th Tank Battalion. My full-length interview with "Klap" is included in the audiobook "Once Upon a Tank in the Battle of the Bulge," which is available in my eBay store and at oralhistorystore.com.

Track 11: Tim Dyas

Tim Dyas was a sergeant in the 82nd Airborne Division who was captured during the invasion of Sicily. In this excerpt he describes the emotionally wrenching decision to surrender his men, despite being faced with the certain death of all of them. My full-length interview with Tim is included in the autiobook "POW: Right in the Keister," available in my eBay store.

Track 12: Erlyn Jensen

In this excerpt, Erlyn describes her mother's participation in Gold Star Mothers, and her mother's trip to St. Avold, to see her son's grave. Although this is the third excerpt from one interview, it's intended to give you an idea of the depth of the full-length interviews. A full-length interview with Ed Boccafogli, for example, is available on the home page of tankbooks.com. My full interview with Erlyn is included in "The Kassel Mission: An Oral History Epic," available in my eBay store.

Track 13: Jerome Auman

In this excerpt from my audiobook "Four Marines," Jerome Auman talks about a reunion of his unit in which he encouraged his fellow veterans to write their stories. Spoiler alert: Keep a handkerchief nearby. Jerome's full-length interview is included in "Four Marines" and is available in my eBay store.

Track 14: Vern Schmidt

Vern Schmidt was a replacement private first class in the 90th Infantry Division. He and two other young men were assigned to the division in the Siegfried line, and in ten days, the two men he joined with were dead. My full-length interview with Vern and his wife Dona is available as a double CD, "Kill or Be Killed," available in my eBay store.

Thanks for listening. Your purchases help fund the substantial project of digitizing and making available my archive of more than 600 hours of audio interviews with the men and women of the Greatest Generation. If you'd like to sign up for my email newsletter, please send me an email at: aelson.chichipress@att.net.

Published on May 08, 2016 10:02

January 24, 2016

Ira Weinstein, 445th Bomb Group, POW, Kassel Mission Survivor

Ira Weinstein at Thunder over Michigan. Ira passed away Jan. 24, 2016. He was 96 years old.This was one of Ira's favorite stories: