Aaron Elson's Blog, page 12

January 13, 2018

S***hole Story No. 2 (no pun intended)

Bob Rossi, 712th Tank Battalion veteran Another story with a very contemporary theme from my World War II Oral History archive. Bob Rossi was one of my earlier interviews, back in 1992. He was a source of many stories in my book "Tanks for the Memories," and his full-length interview is included in the audiobook "Once Upon a Tank in the Battle of the Bulge." He joined the 712th Tank Battalion as a replacement in September of 1944. In this excerpt he recalls an incident shortly before he joined the battalion.

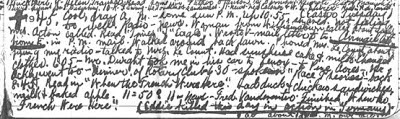

Bob Rossi, 712th Tank Battalion veteran Another story with a very contemporary theme from my World War II Oral History archive. Bob Rossi was one of my earlier interviews, back in 1992. He was a source of many stories in my book "Tanks for the Memories," and his full-length interview is included in the audiobook "Once Upon a Tank in the Battle of the Bulge." He joined the 712th Tank Battalion as a replacement in September of 1944. In this excerpt he recalls an incident shortly before he joined the battalion.Bob Rossi: "We wound up, this is a funny story, we wound up in this replacement depot. Now this is my life, living in barns, stables. We were all replacements, and the way they fed you, a section at a time, they would throw all these C rations together, they made like a stew out of it, and you were allowed one scoop of this meal, a canteen cup of coffee, a slice of bread, and a pack of cigarettes. And a tropical hershey bar, or we had some other bar that they gave us which was like a fruit bar. And this one time I wound up with a pack of Lucky Strike green cigarettes. The phrase was 'Lucky Strike has gone to war.' I wound up with Lucky Strike green cigarettes. I was a celebrity. 'Let me see that, let me see that.' "They had a mound of cigarettes on a table. As you went by they gave you the cigarettes. You could get Chesterfields one day and Camels the next. The first pack they grabbed they gave you. "We had to clean out these stables first to make them habitable for us to live in, and we got our bedrolls on the ground, and finally they assigned us jobs while we were waiting to be shipped out. And they assigned me to be in charge of this latrine. Now it's a little distance from where we're staying in the stable. And what it is, I have to keep this 55-gallon drum full of water, make sure there's toilet paper, they had toilet stalls, no seats on them. And as the guy came in, there was an old slate urinal with the disinfectant powder. And I have to keep this place clean. Hose it down and what have you. "Now I'm doing this for two days. And as the guys would come in, they would take their steel helmet off, grab a helmet full of water, use one of the stalls, then flush it down. "Now the third day I'm on the job, I've got everything cleaned up, a detail is coming toward me. They're walking toward me, they've got buckets. So I'm standing in the doorway, and one of them, I don't know if it was a sergeant or an officer, says to me, 'Okay, soldier, you want to get out of the way?' "Underneath me, I was standing on a trap door, is all the crap in God's world. That they're flushing down. These guys had to scoop it out into the buckets. I said that was a real s*** detail they were on. "That's the type of latrine I was in. Further away, they had what looked like sentry boxes, but they were on a platform. And the guys would take a crap, and it would go into cans, and they'd just keep changing them. "We were all ready to leave, we've got the full field pack on, we're not allowed to take our stuff off, because we don't know when the trucks are coming. And who pulls up in a staff car, Marlene Dietrich. And she looked like hell. She had the helmet on, olive drabs. So maybe ten, fifteen minutes later, she comes out on stage. She had a beautiful red gown, a shimmering gown, she sits down, pulls up the gown, she shows off those famous Dietrich legs. Then she sang. Then we got on the truck, we had to leave."

- - - Bob Rossi's full two-hour interview is included in the World War II Oral History audiobook "Once Upon a Tank in the Battle of the Bulge," along with a group interview with four of the five crew members of a tank that was knocked out on Jan. 10, 1945, and individual interviews with the other four crew members.

Once Upon a Tank in the Battle of the Bulge

Once Upon a Tank in the Battle of the BulgeIn case you missed it: S***hole Story No. 1

Published on January 13, 2018 15:25

The Captain of the Head: A Shithole Story

Bob Hamant, "A Marine on Tinian" A certain word has been much in the news lately, and it reminded me of a story I recorded several years ago during an interview in Cincinnati with Bob Hamant. Bob spent a year with the Marines on the island of Tinian during World War II.

Bob Hamant, "A Marine on Tinian" A certain word has been much in the news lately, and it reminded me of a story I recorded several years ago during an interview in Cincinnati with Bob Hamant. Bob spent a year with the Marines on the island of Tinian during World War II.The story, one of many Bob told during the interview, which was arranged by his daughter, began with a discussion of the atomic bomb.

"Toward the end of the war," Bob said, "they issued us wool socks, wool pants, jackets, wool sweaters, gloves. Hell, it's 90 degrees on the average [on Tinian], what are they gonna need that for? And nobody knows anything, but they gave you all this survival training for the winter. Hell, the only place they could take would be Alaska and we already owned that. But one thing we did have while we had that stuff, one of the guys says, 'Hey, there's a big plane up there on the airfield,' and he says, 'They're doing something to the bomb bay doors.'

"Somebody says they're going to take a bigger bomb.' [The Enola Gay, which dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima, took off from Tinian.] "Well, if you want to keep something a secret, you put guards around it, so then everybody comes up and looks. And we asked the guards. They didn't know. They just said they're doing something to the bomb bay doors, and that's it. 'We're supposed to keep everybody away.'

"Hey, the bigger the better that you could drop on them. Well, nobody knew what an atomic [bomb was]. And so we found out. They notified us that they dropped an atomic bomb on Japan, and in the area where it dropped nobody will be able to live for 45 years. And we thought if they drop a couple more, we'll go home and everything will be fine. I don't know how many days it was later on they dropped the second one, and they came down and said, 'Turn in all your winter gear.' And then they told us we were supposed to make an invasion on northern Kyushu, which has snow, and they expected like 85 percent casualties because the Japs were gonna fight to the last man and old woman, and the cold. They said we'll lose almost half the guys from the cold alone, with frostbite.

"So we were really glad we didn't have to go. But anybody comes along and says we were horrible for dropping the atomic bomb needs their head examined. There are thousands and thousands of guys, maybe millions of them, that are living today because they dropped it. And probably in Japan too, it probably saved a lot of their lives."

"You mentioned the prospect of frostbite," I said. "What about malaria?"

I'm not 100 percent sure what made me ask that, but I thought since Tinian was a tropical island, it might have been a problem.

"That was more or less in the Philippines," Bob said. "There was no malaria on our island."

"Even with all the mosquitoes?" I asked.

"No, we had mosquitoes," Bob said. "There's something I forgot to mention was flies. You can't imagine the amount of flies. At night the flies would go and land on a tree, and a little twig would wind up to be a big branch because the flies were on top of flies. And when you went to eat, when you opened that can, the flies were on it like that. Your food disappeared, so we had to figure something out. We had mosquito netting, you'd pull it over your head and try to eat, but after a while you weren't so persnickety, you'd eat flies. When you went to the john, there'd be maybe ten million flies in there and you almost didn't have to wipe your butt because the flies were so thick. It was pitiful.

"Oh, that's another story I could tell you. I got put on as captain of the head. That means you've got to clean the heads. So I had an oxcart that I would bring around and it had gasoline on it. I'd throw a cup full of gasoline down each one of the holes and roll up some toilet paper, set it on fire, toss it in the hole, step out the door, and it'd go 'Whooooff!' And it would kill all the flies.

"Well, I ran out of gasoline, so I told the truck driver, 'I need more gasoline.'

"He said, 'Okay.' He brings out a 55-gallon drum, and we put it on the oxcart, and I went in there and I threw a cup full of gasoline down each one. This was different, it's an eight-holer, and I rolled up the toilet paper, lit it, threw it down there, closed the lid, stepped out, and there was the biggest explosion you'd ever want to see. I got hit by the door, and about two or three hundred feet up in the air there was toilet paper flying. Here they gave me aviation gas. I was just getting the regular old gas. I blew that thing all to hell. But I was just lucky the door hit me, and nothing else. I was clean. That was funny. And they gave me another name for that, I forget what that one was. 'Don't go to the john when Hamant's around!'"

Order the full two-hour audio interview with Bob Hamant from my eBay store:

Bob's interview is included along with three other interviews in the audiobook "Four Marines."

Hear Bob Hamant tell the story

Hear Bob Hamant tell the story

Published on January 13, 2018 12:18

December 31, 2017

The saddest story I ever heard

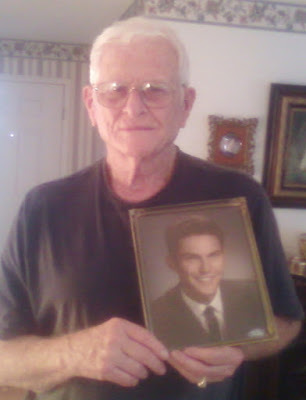

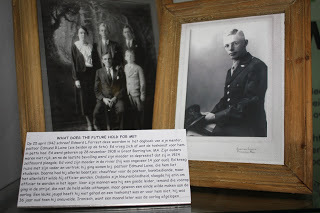

Paul Swofford in 2009, with a photo of his son

Paul Swofford in 2009, with a photo of his sonWay back in 1999, before they invented bucket lists, if I had had a bucket list at the time it would have included getting lost in every state in America. I got lost in Illinois once, looking for Russell Loop, a veteran of my father's tank battalion. I drove past miles and miles of farmland, corn fields if I remember correctly, and his instructions were to look for a store in the center of town -- the town being Indianola, Illinois, follow a state road to the end, then turn right. Only I followed the wrong state road and it didn't end, and it was dusk, and my car was low on gas. After several miles the road ended and I turned right and saw a house, so I knocked on the door and a young woman holding a baby answered and she never heard of Russell Loop and I wasn't in Indianola anymore. So I doubled back to the store and took the other road and eventually found his house. I got lost in a parking lot in Fort Mitchell, Kentucky once. In my defense it was the parking lot of the Drawbridge Inn, which is like a corn maze without the corn. But O.J. Brock, one of the youngest of the battalion's veterans, in his early seventies at the time, had brought his Harley-Davidson to the reunion on a trailer and wanted to put it in a storage facility, and asked if he could follow me out of the parking lot. That was pretty embarrassing, but I eventually found the exit.

Florida, well, I could have crossed that one off a few times. I almost never met Paul Swofford, one of a number of veterans of the ill-fated Kassel Mission of Sept. 27, 1944, on my interviewing trip in 1999. He lived in Lakeland. There was a brand new road called the Polk Expressway and I got off at the wrong exit and drove around an airfield called Drane Field at least two times. GPS was a relatively new phenomenon and the closest thing to a cell phone was Maxwell Smart's shoe. Again it was getting dark and I finally pulled into a strip mall, found a phone booth and called Paul. Turns out the entrance to the development he lived in was an easily missed road off the new expressway's service road, but I finally did find it, and we talked for more than two hours.

Lt. Paul Swofford, rear, and his navigator, bombardier and co-pilot. That's Paul Swofford with the long face in the picture while three members of his crew are celebrating after a mission was scrubbed. The way he explained it, that would have brought him one more mission closer to completing the 35-mission requirement. Plus the responsibility for his crew as the pilot weighed heavily upon him.

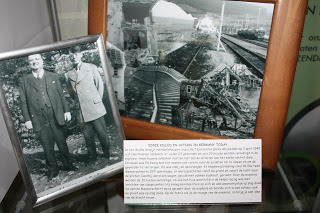

Lt. Paul Swofford, rear, and his navigator, bombardier and co-pilot. That's Paul Swofford with the long face in the picture while three members of his crew are celebrating after a mission was scrubbed. The way he explained it, that would have brought him one more mission closer to completing the 35-mission requirement. Plus the responsibility for his crew as the pilot weighed heavily upon him.Thanks to the efforts of veterans like George Collar and his son Doug, and Bill Dewey and his daughter Linda, and Walter Hassenpflug in Germany and a young Belgian, Luc Dewez, the Kassel Mission is slowly taking its place in the annals of history, where it previously was relegated to little more than a footnote: biggest one-day loss for a single bomb group in 8th Air Force history. Thirty-five B-24 Liberators of the 445th Bomb Group flew off course and lost their fighter protection that day, and were ambushed by 100 to 150 German fighter planes. In a battle that lasted by most accounts about six minutes, 25 bombers and many German fighters were shot out of the sky before the American P-51s and P-47s, responding to a flurry of Mayday calls, arrived and the German planes skedaddled.

All of the surviving bombers were damaged, some of them heavily. Three crash-landed in Allied-occupied territory. Two reached an emergency landing field in Manston, England. One was forced to overshoot the 445th's base at Tibenham, England, because there was construction equipment on the runway, and crash-landed five miles away. Four planes made it back to Tibenham.

Paul Swofford was the pilot of one of those four. Shells from a Fokke-Wulf 190 had shattered his windshield and both Paul and his co-pilot had shards of glass in their face. One of the Liberator's four engines was shot out. The hydraulics didn't work. As he approached the base, Paul had his engineer fire flares to signal there was a wounded man on board. In response, the personnel on the ground fired red flares, denying him permission to land, because he was approaching a taxiway rather than the runway. The engineer would have to hand-crank the landing gear up and Paul would have to climb to 500 feet, and he didn't think that was possible. But the engineer succeeded, Paul circled the airport and landed successfully.

Paul kept his anger at the ground personnel inside all those years -- 45 of them -- and he remained angry until the day he died, but talking about it in an interview for the first time kind of opened up the floodgates. He bought a new computer and got onto the Internet and began downloading pictures of all sorts of airplanes that he put in a scrapbook. He spoke to Bill Dewey, who piloted one of the planes that reached Manston, and he even came to an 8th Air Force reunion at which the 445th had a hospitality room.

In his house in Florida, Paul had a small room set aside for his memorabilia from 24 years in the Air Force, from which he retired as a lieutenant colonel in 1966. He had an embroidered B-24 that he picked up somewhere mounted on a wall. He had certificates for flying so many thousand hours in different aircraft. He had served in the Strategic Air Command.

In the memorabilia room, I noticed a figure, a doll really, of the ventroliquist's puppet Mortimer Snerd holding a baseball glove. I asked Paul about it.

That was his son's baseball glove, he said, and Mortimer Snerd, who along with Charlie McCarthy was part of the ventriloquist Edgar Bergen's act, was his son's favorite character. His son was killed in an automobile accident when he was 19. Paul and Sybil didn't have any other children.

I think that's what created a bond between Paul and me, unlike my relationships with other veterans I've interviewed, although I often visited Dorothy Cooney, the girlfriend of my father's buddy who was killed and who never married.

Over the next few years I visited Paul on a number of occasions.He and Sybil, Baptists, were very religious. It was the embrace of religion that kept their marriage from falling apart after their son was killed, Paul said. Sybil, god bless her, eventually stopped trying to help me find Jesus, but I don't think she ever gave up hope.

I posted several of my interviews with veterans of the Kassel Mission, including Paul, on my web site. One day Paul and Sybil were in church and his pastor read aloud a portion of Paul's account of the battle that he downloaded. He didn't say whose account it was. When he reached the end, he asked Paul to stand up.

A Congressman was in church that day. A few weeks later, in a ceremony at the church, Paul was awarded the Silver Star.

Sybil and Paul at the Silver Star ceremony.

Sybil and Paul at the Silver Star ceremony.Although I talked to him on the phone from time to time since then, the last time I visited Paul was in 2009. I brought my tape recorder -- my DVR, that is, having switched to a digital voice recorder a few years before -- because Paul was always reluctant to talk about the Great Depression and Sybil would always prod him to tell me how he loved flying and always wanted to be a pilot, but couldn't afford lessons, and about how poor his family was, which turned out to be a good thing for reasons I'll get to, but it was when she told me Paul was so poor that he took a cow with him to college so he could sell the milk, I said I've got to get this down on tape.

"I want you to tell me a little bit about growing up in the Depression," I said.

"Well, I was living on a farm," Paul said, "and I was in the third grade at school when it started in 1929, but I didn't know anything about what is going on here. I am about eight years old. We noticed it in what we were able to go to the store and buy. I was aware that my folks didn't have any money coming in, and we didn't have biscuits for breakfast any more. We didn't have any biscuits to take to lunch to school. Since we lived on a farm we raised corn, so we had cornbread three times a day. That was one of the things that we noticed. But being a young person like that, I wasn't aware of what all my folks went through.

"My mother and father had 16 children. One of them was born in 1914 and he died after three weeks, but there were 15 that lived, so one of 15 is the way I grew up. I had older brothers in school. Most of the girls came along after me, but to start with there was one girl and seven boys. I was the eighth one, and then the girls finally overtook us, some of them even after I left home.

"The farm was in western North Carolina, in McDowell County, that's where I was born, near Marion, and we later moved to Mitchell County. That's where Spruce Pine was the largest town, so we children went to school at Spruce Pine, and that's where I got my high school diploma in 1937, and if you start counting, you'll see that if I started in 1927 and graduated in 1937 is only ten years there, so when we changed school I conveniently skipped a grade, so all through high school I was the youngest one in school. And when I started college, I was the youngest one in my freshman class.

"Appalachin State Teachers College was close to us at Boone, about 50 miles away, and I had two brothers that were also going to school there. Incidentally, in spite of the Depression and the fact that we didn't have any money at home and so many children, before me there were three of them that got a college education, and so it was just natural when I finished high school that I would also go to college and that's where I met my wife. Sybil says that the greatest thing ever happened to me was that when I came up to my senior year, I dropped out.

"Well, the reason I dropped out is I didn't have any dollars to go to school, and I realized that my senior year I would have to do practice teaching. That means a couple suits of clothes. I didn't have a suit of clothes, and I didn't even have enough money to register, so I dropped out for a year, went out West, at 19, 20 years old, and worked for a year. I came back in '41 before Pearl Harbor and started back in, and about the first day of school Sybil and I met each other, first day of school. I was a senior and she was a freshman, just coming in. And Sybil says the greatest thing ever happened to me was I didn't have any money, had to drop out of school, because I'd never have met her. And that made a lot of sense.

"When I went out West, I ended up working down in California on a ranch that raised sugar beets and aspara -- well, yeah, they had asparagus but mostly it was sugar beets, and my job was to work on a rain machine. They didn't have much rain in the summertime in central California around Sacramento, so we had to lay these water lines, get water out of the canals and pump them with a tractor to put pressure there, and they call them rain machines, the whirling two streams of water. So we'd let that soak for an hour or so and then shut her down, move it over about 50 feet, and set up shop again. That's what I did for about six months out there in the summertime.

"I held onto everything I made and came back and even lived, that's the first time I'd ever lived in a dormitory. In my previous years I had to work for my room and board. It only cost me $25 to register at school. I never did have any textbooks, couldn't afford 'em. I'd go to the library and read their copies but I'd have to turn 'em back in at the end of the hour. I didn't have any problem remembering in those days, like you do when you get a few years on you, sometimes you don't remember what you went to the bathroom for.

"In the dormitory I had a roommate who was about four years older than me but we were both seniors that year, and so I did practice teaching. That was a wonderful experience. Here I was 20 years old and I was doing practice teaching. I was doing practice teaching at the time of Pearl Harbor, in December of '41, and so I graduated in the spring, got a bachelor's degree, and then I went right -- I had told my father and mother all along that I wanted to be a pilot. That's before we were in the war. And my dad would say, 'I'm not gonna sign it for you,' because I was under age. The requirement was to be 21 and have at least two years of college, that was in 1941. But my dad would say, 'I'm not gonna sign it.' But his sly way of telling a joke, I guess, was never to laugh about it but he would say, 'I wouldn't mind flying an airplane at all, so long as I could keep one foot on the ground.' That was his kind of humor. But when I did graduate that year, after Pearl Harbor, they lowered the Selective Service age. That's the ones that signed up for the draft. But a month or two after Pearl Harbor they lowered the age to 20. So I was 20. I signed up in February, I've got the draft card right here with me. From February to my graduation I was on pins and needles because I was afraid I was gonna get drafted before I could get a chance to finish college before I was 21. I knew that the day I was 21 I headed to Charlotte and signed up for the Aviation Cadets. I took the test, of course such things as mathematics and so forth, here I'm just a brand new college graduate, it was no problem to pass the written exam and the physical exam, so I passed, and, well, the rest is history. I did become a pilot for the next 24 years."

It was at this point that I asked Paul about the cow.

"What was it that Sybil was telling me last time I was here with the cows," I said, "that you and your brother took a cow with you across a mountain?"

"Well, we did," Paul said. "Since I skipped a grade, it put me up just one class behind my brother who was two year older, and originally was two classes ahead of me in school. Well, I jumped up, I always thought there's a little bit of resentment there. Of course he isn't alive anymore so I can say that maybe he had a little bit of resentment that his kid brother was nipping at his heels just a grade back of him. But he had married when he was a sophomore in college. At 18 he got married, married this lady who was a senior in college. So he took a cow that was his at home, put it, a neighbor had a truck, and hauled that cow to Boone. And he found a place there to feed the cow and stake it out, and graze the grass, so my junior year, that was the year that was, we'll say 1939 and '40, we had a room in a place that had a bathroom outside and had a shower outside, and he'd milk the cow and sell about half of the milk, he sold it for ten cents a quart, at least half of the milk and we drank the rest of it. So that was the cow. He did most of the business with the cow, he did all the milking and all the selling and all of that. I was just a young squirt to him."

Stephen Ambrose once wrote that he almost thought he developed PTSD from interviewing so many veterans of World War II. When I read that, my reaction was "Phshaw!" But over the course of hundreds of hours of interviews with men and women of the so-called Greatest Generation, I've rethought my reaction to Ambrose's remark. And while I wouldn't say I've come close to post traumatic stress disorder, I've seen many grown men cry, and shed many tears myself, and I've shed them in spades. First I get choked up while the veteran is telling me a particularly sad, or tragic, or poignant story. Then the tears start flowing while I transcribe the tape, or the digital file. I get choked up again when I transfer the file to a CD and again when I play it for patrons at the Reading World War II Weekend, and again when I relate the story to a friend or acquaintance. Next to the veteran who relives the story every day of his life, I probably replay some of the stories more than anybody else. But don't cry for me Argentina, I didn't live through any of these experiences, and am little more than a conduit to bring the stories to a wider audience.

I asked Paul if there were still a lot of Swoffords in Spruce Pine.

"No," he said. "In my family, we went to the four winds, you might say, because of World War II, or I guess you'd have to go on back to the Depression, because I had two brothers to drop out of school before they graduated from high school and they went out to, quote, "seek their fortune." I don't know why they did it, but they left home when they finished about the eighth or ninth grade. One of those now is 93 years old. There's three boys that we have left in the family with the Swofford name, but, you know, Sybil and I, we lost our son when he was 19, in 1963. He had just completed his sophomore year at the University of North Carolina at chapel Hill. That was on June the 6th, so we were just saying yesterday, I was putting a new calendar for the month of June, I said on Saturday is the fateful day. It was just 19 years after D-Day that he lost his life. He'd just finished his second year at the University of North Carolina and was home for the summer, and I was on temporary duty, we called it TDY, out to California, to Merced, checking out in what we call the KC-135 tanker airplane. Incidentally, later, when I came back I was the commander of the KC-135 squadron. I was the commander of the field maintenance portion of the KC-135 wing, which was a tanker wing. That airplane was originally the DC-9 that the airlines used. Douglass built that DC-9."

"So you were overseas when your son was born?" I asked.

"No," Paul said. "I went overseas in '44. It took about a year to go through flight training, and then nearly another year to train on the B-24 to go to combat. So it took about two years to get ready to go to combat. So I went over, I left at the end of June of 1944, it's just in the same month as D-Day was the 6th of June of '44. So we were given an airplane. From our training camp we went to Topeka to pick up an airplane. They gave us a brand new airplane. I had a crew of ten on that airplane, and we flew it across the northern route, up through eastern Canada and Greenland and Iceland, to the British Isles, and we became part of the 8th Air Force."

"When was your son born?" I interrupted.

"Our son was born in '43, about a year after we were married. He had his first birthday, well, just about the time of the Kassel Mission. There's only a couple of us on the crew who were married. It wasn't always easy for the other members to understand what being married meant, how the two of us who were married and had children, we knew how to communicate with each other, you might say, easier than it was with the other fellows. The other crew member who was married was Joe Waller. He was my ball turret man, but we got to England, and the first thing they said, 'Give us this airplane, we're gonna send it somewhere and take the ball turret off of it.' Well, when we got to our combat group they says, 'You've got to eliminate one of your men since we don't have a ball turret.' So we discussed it with my co-pilot and my crew chief, because those are the ones I'd always consult on matters like that, and I said, 'Well, what do we do?' And it was unanimous among us three that we eliminate one of the others and keep Joe Waller and put him in another position, because we didn't want to lose him. We made him the tail turret gunner. He was the first one to see the enemy on my aircraft on the Kassel Mission because he could see them coming in from the rear. He had one definite kill and one probable. And my engineer manned the upper turret all the time. Normally the engineer would be standing up between the two pilots, and we'd talk about the functioning of the airplane, the functioning of the engines and so forth, so we had to have him there to talk to us. But when we would get into enemy territory, he would man the upper turret. He had a probable, we had one kill and two probables assigned to my crew."

"You had said Steve's first birthday was around the time of the Kassel Mission?" I asked.

"Yes," Paul said. "He was born in October of '43 and that was in late September of '44, the Kassel Mission, so he was just short of his first birthday there."

"And it was June 6th that the accident was?"

"That's right. June 6th of 1963. Just about four months, a little more than four months short of his 20th birthday. He came home for the summer and as I say I was in California, and he he had come home for the summer and another young fellow there that he palled around with, we lived on the base, in base housing, and I was assigned out to California for that KC-135 school, and Sybil was there alone, and she went down to Chapel Hill and picked him up and brought him back home, and the two boys, our son and the other boy, the other boy had his father's car, and so they were out on the afternoon there, just before they were both going to have a job for the summer. And the boy, the driver, decided to pass another car and happened to be right on a rise. I don't know why, it would have been surprising because it was almost in front of the high school that both of them had attended. They were familiar with that road. He decided to pass on the rise. It went head on into another car. The other car was driven by an airman's, a sergeant's, wife, from Lockbourne Air Force Base where we were, in Columbus, Ohio, and the sergeant's wife was killed also in the accident. Head on. And our son was killed, and the driver, a young driver about the same age as our son, had a broken arm. That's, that was the end of our descendents, right then and there.

"Well, it just so happened that particular day, the 6th of June, had long been my graduation day from KC-135 schooling in California. That was at Merced, it was Castle Air Force Base, and we graduated in the morning. Of course, being three hours later out there, by the time I started home from there, about noon, I started driving east. I had my own automobile out there, and so that was about 3 o'clock Eastern time, and about noon time out there that I started driving, and towards evening, it was approaching darkness, somewhere around Needles, just before I was to get into, I don't remember if I had come into Nevada or Arizona, they're both pretty close there, as I was approaching Needles I decided as it got dark that I would find a motel. So I saw one and I just drove right into the driveway, near the office, and I looked in my rearview mirror, and right on my rear bumper was a highway patrol. And I got out of my car and I says, 'Well, Officer, is there a problem?'

"He asked me if I was Major Swofford. I was a major at the time. And he said, 'Call your command post.'

"I'd never heard of such a thing, but apparently the authorities back at Lockbourne in Columbus had called, they had first contacted the military at Merced and they said I'd already left, heading east. And so, I don't know where they got information about the car, the policeman, the highway patrolman, had been alerted to, I think all of the patrol were alerted to look for me. And they said, 'Call your command post.' So I just, before I even checked in at the motel, I went over to find a place to call, and there was one pay phone in all of that little, it was just a village then, Needles, that's quite a while ago, and there was one pay phone that was available, and there was a long line there and so I had to get in line. I got in, and it was always arranged when we were away from the base that I could just put in a quarter and call and the number that I would call, they would return the quarter to me. And so I got the base number and called and talked to my commander, and the commander told me that my son had been killed that very day. And so, so then, I had, well, I had the commander to give me back the command post there, it was hard for me to talk, like it is now, really, after 46 years it's hard. But he gave me the command post that was on the base, and I asked them where I was. I says, and they told me, said you're just, I was 100 miles south of Nellis Air Base, which is in Las Vegas. And so I asked them while I was on the phone there, 'How about you making arrangements for me,' I says, 'I can drive up there but I don't know, you find,' I says, 'I have no way of knowing what airplanes are flying' and so forth. So the people at the command post got ahold of the airline out in Las Vegas that was near that air base in Las Vegas, and they found out that that there was a plane heading east at a certain, about two hours from there. And they says, 'We told them if you didn't get there to hold it.'

"Well, that was a pretty hard drive, you know, at night, a hundred miles, and I had to go across Boulder Dam, late in the evening, and Boulder Dam, strange territory, at night, by myself, without even knowing where I was, but I finally got to that airfield up there in Las Vegas, that's 100 miles away, and they were holding the airplane for me.

"And when I had talked to the commander earlier, he told me they couldn't, what time of day our son had lost his life had been about 4 o'clock in the afternoon, they couldn't find Sybil. Sybil had gone up to town and was spending the night in town somewhere, and they hadn't found her yet, so I heard the news before she did.

"Well, before, when the commander told me that, there were people outside the phone booth there in Needles wanting to, they wanted the telephone, they were clamoring there for me to shut up and get out. And since they couldn't find Sybil there's no point in me calling her so I called Sybil's mother. Steve was the first grandson, he was the light of their life, and I started off by saying I'm out in the middle of the Mojave Desert in Needles, California, and she says, 'Well, how wonderful! How are you gettin' along?' And I says, 'I didn't call for that.' I says, 'Steve is dead.' And I know that shocked Sybil's family head to toe. But I got up there and got on that airplane, left my car there, parked there in the lot, and headed East, and the next morning I was at home in Columbus. And Sybil met me at the door as I came in. That's a tough time."

"What sort of a kid was he?" I asked. "Was he like an Air Force brat?" As the words came out, it occurred to me that that wasn't the most sensitive thing to say. "Air Force brat," I tried to correct, "that's not ..."

"I know what you mean," Paul said. "He didn't much like the idea of me being in the military. It didn't send him any at all. But he was a wonderful, wonderful, young fella. Look over your shoulder."

Paul holding the picture of his son that was on the wall. "Oh my goodness," I said. "He was a good looking kid."

Paul holding the picture of his son that was on the wall. "Oh my goodness," I said. "He was a good looking kid.""That's made when he was 19," Paul said. "That's just ... missed him every day. And so has Sybil, but she's not as vocal about it I guess as I am. I'm the one in our household brings his name up all the time.'

"Well, after that, I'd already had three tours overseas -- one tour in England in combat, later had a tour in, just at the end of the war, '46 to '48, in Okinawa for about a year and a half, and left them at home. And then in the mid-Fifties I was sent up to Thule in northern Greenland for a year and left them at home. And it came up to 1965 and I was approaching 24 years in the military. That's when I was the commander of my field maintenance squadron at the time. I was still on flying duty, and so I took a Gooney Bird, that's a C-47, took it to haul some Strategic Air Command personnel. We were part of the Strategic Air Command or SAC as we called it. I had to take some of their personnel to some of the outlying sites down in Oregon like stopping at Portland and so forth, and I learned by looking at my manifest that they were from the personnel section at headquarters Strategic Air Command at Offutt Air Force Base in Omaha. So I turned the controls over to the co-pilot and I says I'm going back and talk to this chief of personnel back there. And when I saw him, I says, 'I've been stationed at Lockbourne Air Force Base there in Columbus for eight years. I'm eligible for retirement. I says I've got 23 years, and I says, 'Do you have anything open down in Florida where I can spend my last years in the military?'

"He says, 'You mean you've been stationed here for eight years? Why, you're hot to go to Vietnam.'

Of course, the Vietnam business had just started a little bit before, and when I came back from the flight, I said to Sybil what happened there. She said, 'What time does the personnel office open tomorrow morning?' I didn't have to ask any questions. I knew what she meant. And I did it. I was there when they opened up the next morning. I says, 'I want to put in for retirement.' So I put in for retirement there, and I asks the personnel chief, I says, 'How safe is this now? If something happens after this, can it be called off??''

He says, 'Negative.' He says, 'You put in for retirement and we accept it,' he says, 'you'll retire.'

Well, that same personnel office, about ten days later, called me at my office and says, 'I've got a Twix [TWX] for you.' That was the military message, and he says, 'You need to come over to the personnel office and read it.'

"Well, when I got over there and opened it up, it says, 'You have been reassigned to Tan Son Nhut Air Base in Vietnam, in Saigon, and to report immediately and be the chief of maintenance there.' And I just laughed like I laugh right now, and I says, 'Well, Colonel,' I was a lieutenant colonel at the time also, I says, 'That's hilarious, isn't it?' I says, 'I'm safe, right?'

"He says, 'You're safe."

Because Sybil had said, 'I don't want you ever to leave me again.' She says I've been away too much, we lost our son, and she says, 'If you went over there, in the first place you may not come back, and the other is, we're gonna be apart.' So I retired in about six months then in January of 1966, got credit for 24 years service, pay wise that means 60 percent of base pay for retirement."

These are the three tracks from the interview in which Paul talks about his son:

Paul Swofford 2009 interview track 4

Paul Swofford 2009 interview track 5

Paul Swofford 2009 interview track 6

Edgar Bergen and Mortimer Snerd, Steve Swofford's favorite character

(Paul Swofford passed away on April 20, 2016, eight days shy of his 95th birthday. Sybil Swofford lives in an assisted living facility in Florida.)

Published on December 31, 2017 22:10

October 8, 2017

widows and siblings

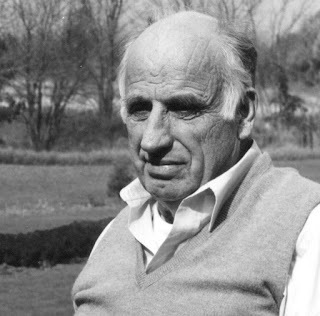

Elizabeth and Wally Lippincott, 1944

Elizabeth and Wally Lippincott, 1944More than 400,000 young Americans were killed in World War II. Add the number of Russians, Germans, other nationalities, and the figures boggle the mind. Every one of those 400,000 and all those others had a mother, a father, many had brothers, sisters, some had children. My sister Arleen had a friend from childhood whose father, several years ago, was in his nineties. "You should talk to him," my sister said. So I paid him a visit and asked about his brother. He declined to talk about him. All these years later the pain was still intense. Tom Stumpner of Eagle Lake, Wisconsin, had an uncle who was killed in the war. He only knew him as "Uncle Bud." His mother would never talk about her brother. When she was near the end of her life, she gave Tom a chest with all of "Uncle Bud's" memorabilia: snapshots, letters, papers. Only then did Tom learn his uncle's real name, John Daum. Tom sent copies of the letters and photos to the web site of the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment, John's outfit, which posted them online as a way of keeping John's memory alive.

Over the years, I've interviewed a number of women who lost their husband in World War II, as well as brothers and sisters who lost a sibling. I've taken eight of those conversations and turned them into my newest audiobook, "Widows and Siblings." To say there is anything universal in eight conversations out of hundreds of thousands that could have been conducted would be a mistake. Even the eight differ greatly in their circumstances and the types of stories that are told. Although it would be safe to say that each of the deaths in combat deeply affected many people. That goes for victims of gun violence today, all you have to do is read news accounts. And while there are moments of deep poignancy in the conversations, there are also moments of great humor. Like the time Erlyn Jensen was talking about a trip her mother took to see her son's grave in the cemetery at St. Avold, France. I got all choked up at one point in the story and Erlyn said, "If you're gonna cry now, just you wait!" I've always been touched by the humor in that warning. Erlyn and Sarah Schaen Naugher, whose husband was killed in the same air battle as Erlyn's brother, were being stand-offish to each other at the 2008 reunion of the Kassel Mission Memorial Association. Sarah felt it was worse to lose a husband in the war than it was to lose a brother, but try telling that to someone who was 14 years old and whose big brother was her hero when he was killed. The two women have since made up and are great friends. These are the people you'll meet in "Widows and Siblings":

Over the years, I've interviewed a number of women who lost their husband in World War II, as well as brothers and sisters who lost a sibling. I've taken eight of those conversations and turned them into my newest audiobook, "Widows and Siblings." To say there is anything universal in eight conversations out of hundreds of thousands that could have been conducted would be a mistake. Even the eight differ greatly in their circumstances and the types of stories that are told. Although it would be safe to say that each of the deaths in combat deeply affected many people. That goes for victims of gun violence today, all you have to do is read news accounts. And while there are moments of deep poignancy in the conversations, there are also moments of great humor. Like the time Erlyn Jensen was talking about a trip her mother took to see her son's grave in the cemetery at St. Avold, France. I got all choked up at one point in the story and Erlyn said, "If you're gonna cry now, just you wait!" I've always been touched by the humor in that warning. Erlyn and Sarah Schaen Naugher, whose husband was killed in the same air battle as Erlyn's brother, were being stand-offish to each other at the 2008 reunion of the Kassel Mission Memorial Association. Sarah felt it was worse to lose a husband in the war than it was to lose a brother, but try telling that to someone who was 14 years old and whose big brother was her hero when he was killed. The two women have since made up and are great friends. These are the people you'll meet in "Widows and Siblings": James Bynum: James' older brother, Quentin "Pine Valley" Bynum, was the tank driver who gave my father a lift to the front in Normandy, and who later was killed during the Battle of the Bulge,

Elizabeth Pitner: Elizabeth and Wally Lippincott were married for only eight months, five of which he was overseas before he was killed at Bras, Luxembourg, on 14 January 1945. Mrs. Pitner remarried, but she never got over Wally and said she believed he would have wanted her to remarry.

Elmer Forrest Elmer Forrest: The only name I remembered from my father's stories was that of Ed Forrest, a fellow lieutenant who was killed. Ed was from Stockbridge, Mass., so one day in 1994 I called information and asked if there were any Forrests in Stockbridge. I got the phone numbers of three Forrests in Lee, a neighboring town. Elmer was the first one I called. I asked if he was related to an Ed Forrest who was killed in World War II. After a moment's silence, he said, "He was my brother." Myron Kiballa: Myron had just gotten out of the hospital after being wounded in Italy when he learned in a letter from his family that his brother Jerry had been killed in Normandy. "It was like I was in the twilight zone," he recalled. "That was the worst letter I ever got."

Elmer Forrest Elmer Forrest: The only name I remembered from my father's stories was that of Ed Forrest, a fellow lieutenant who was killed. Ed was from Stockbridge, Mass., so one day in 1994 I called information and asked if there were any Forrests in Stockbridge. I got the phone numbers of three Forrests in Lee, a neighboring town. Elmer was the first one I called. I asked if he was related to an Ed Forrest who was killed in World War II. After a moment's silence, he said, "He was my brother." Myron Kiballa: Myron had just gotten out of the hospital after being wounded in Italy when he learned in a letter from his family that his brother Jerry had been killed in Normandy. "It was like I was in the twilight zone," he recalled. "That was the worst letter I ever got." Maxine Wolfe Zirkle and Madeline Wolfe Litten: The identical twin Wolfe sisters were 16 years old when their brother Billy Wolfe, 18, was killed in Pfaffenheck, Germany, on 16 March 1945.

Sarah Schaen Naugher: Sarah's husband, pilot Jim Schaen, was killed on the Kassel Mission of 27 September 1944.

Erlyn Jensen: Erlyn's brother Bill, who was known to the 445th Bomb Group as Major Don McCoy, was the command pilot on the Kassel Mission when his plane was shot down.

Kay Brainard Hutchins: Kay had one brother who was a prisoner of war and another who was missing in action, so she joined the Red Cross and went overseas as an air club hostess. Her brother Bill survived the war but Newell Brainard, a co-pilot on the ill-fated Kassel Mission, did not. Some of these interviews are included in other sets, but this is the first time they've been together in one group, and several of the CDs are not in other sets.

Check out my eBay listing for "Widows and Siblings"

Published on October 08, 2017 20:42

July 20, 2017

"So long kids, and if I never see you again, goodbye."

In the highly charged political atmosphere of today, I recently remembered a quote from Erlyn Jensen. Erlyn is the kid sister of Don McCoy, who was a major in the 445th Bomb Group. Major McCoy was the command pilot on the ill-fated Kassel Mission bombing raid of 27 Sept. 1944, in which the 445th suffered the highest one-day losses for a single bomb group in 8th Air Force history. Erlyn said her mother blamed President Franklin Roosevelt for her son's death, because Roosevelt campaigned for reelection in 1940 on a promise that "our boys will not fight overseas." "That was his mistake," Erlyn said when I interviewed her in 2009, "ever making that promise." Myron Kiballa grew up in the coal mining town of Olyphant, Pennsylvania. After his father's death, his brother Gerry, five years his senior, became his father figure. Gerry "always had tough luck," Myron said when I interviewed him in 1996 for a book I was writing about Hill 122 in Normandy. "I remember I was just a kid, he's playing ball, and there was just a lot, and then the road. He hit a ball and he's running over first base, you couldn't stop, and sure enough, a car hit him, broke his leg. Then he got a trick knee. When I talked with Jim Rothschadl [the gunner in the tank in which Gerry Kiballa was the assistant driver], he told me, 'Did you know,' he said, 'your brother had a bad knee?' "I said, 'I certainly did.' "And he says, 'Boy, he struggled with it.' He said, 'You know that they wanted him to take a transfer out of the tank outfit and put him in the medical unit, and he said he wouldn't go. He said that if you want to release him altogether he'll go but he says he doesn't want to go to another outfit.'" Gerald Kiballa was one of nine crew members killed when four tanks of the 1st Platoon, C Company, of the 712th Tank Battalion ran into a group of concealed anti-tank guns after going to the rescue of an infantry battalion that was surrounded by elite German paratroopers on 10 July 1944. When Gerry was killed, Myron Kiballa was 19 and had just gotten out of the hospital in Italy after being wounded at Anzio. "When I got the letter from home," Myron said, "it was one of the most unpleasant letters of my life. Oh, gosh. It turned me into a person like if I was in the twilight zone. When I was reading that letter, it was a horrible letter. Gosh, I opened the letter and the first thing it says that your brother Gerry was killed. And going down the line they said that they haven't heard from my brother John for three months, they were afraid maybe something happened to him, too. He was in the Philippines with the infantry." (John, one of five Kiballa brothers who were in the service, survived the war, as did Myron's two other brothers.) "Now they've had it!" Newell Brainard, a co-pilot in the 445th Bomb Group, wrote in a letter to his mother and sisters upon learning that his brother Bill was a prisoner of war. "We'll go after those S-Bs and get Bill back with us. I just received Betty's letter in which she told me the good news. Of course it doesn't sound like good news to most people, but I'll settle for prisoner of war anytime. He will be treated all right, I am sure." On 27 Sept. 1944, the 35 B-24 Liberators of the 445th Bomb Group strayed off course and were ambushed by as many as 150 German fighter planes. In one of the most spectacular air battles of World War II, 25 bombers and many German fighters were shot out of the sky. Newell Brainard bailed out of his burning plane, but would never get the chance to become a prisoner of war. He landed in a labor camp, and was murdered by one of the guards.

Quentin Bynum's mother, Mabel Claire Murphy Bynum, had a "tongue that could rival that of a mule skinner," said Quentin's younger brother James Bynum. The Bynums lived in Stonefort, Illinois, in the heart of the Ozarks. When Quentin was a few months old he came down with what most likely was diphtheria, of which there was an epidemic in 1919, following the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918. The local doctor pronounced him dead, but Quentin's mother, Mabel Claire Murphy Bynum, didn't mince words and barred the door when the doctor tried to leave, said James, relating family lore, as he had not been born yet. The doctor told Mrs. Bynum to warm the baby by the fire of the cookstove, and soon, Quentin came back from the dead. In 1987 I went to a reunion of my father's tank battalion from World War II. I found three veterans who remembered my dad, 2nd Lt. Maurice Elson, who died of a heart attack in 1980, and all the stories he told when I was a kid came back to life. One of the three, Jule Braatz, was the sergeant my father reported to as a replacement lieutenant. "We were in this field surrounded by hedgerows," Braatz said. "Usually battalion headquarters would assign replacements to a company, and I guess at that time I was the only one that had lost an officer, so they assigned him to my platoon. "Lieutenant [Ellsworth] Howard brought him over and introduced him to me and said, 'This is your new lieutenant,' and your dad was very candid and said, 'Hell,' he says, 'I don't belong here. I'm an infantry officer. I don't know anything about tanks.' And I says, 'Well, I'm gonna start to teach you.' So we got up on a tank and we got inside and I showed him this and that, and we got out, and we walked down the front of the tank, and I says, 'Now, be careful when you jump off of these things, because you don't have a flat space, and you could jump off and twist your ankle.' And so help me God he did. So then, we took him to the medics. "I have no idea how long it was, but in that length of time we got orders to move out, so we moved out. From there on, it's more or less hearsay, or second hand information, in that he came back and we were gone, and instead of maybe waiting, he was anxious to get up there. So about that time the first platoon got orders to move, and he went with the first platoon tanks because he figured he'd be up somewheres where we are, and then he could join us. "He rode in what they called the bog, or the assistant driver's seat down front. The driver was Pine Valley Bynum, who later was killed. And the story is, your father wanted to get out of the tank, and Bynum kept telling him no, because they were getting a lot of mortar fire, but he insisted. So he got out. Bynum says he hardly was out and Bang! A round came in and hit him. And that's the last we heard of your father. The next I heard about him was that he had come back to the battalion sometime in December." Quentin Bynum's fellow tank drivers -- Bob "Big Andy" Anderson, Dess Tibbitts -- said he got the nickname Pine Valley from the area in the Ozarks where he grew up. But James Bynum said there was no Pine Valley in that area. The long-running soap opera "All My Children" took place in the fictional town of Pine Valley, Pennsylvania, but Pine Valley's buddies would have needed a time machine to pin a nickname on him from a soap opera that was launched in 1970. Stranger things have happened, but the likelihood is that when Bynum was in the horse cavalry at Camp Lockett, California, he might sneak off on occasion to the nearby resort town of Pine Valley, California, for a romantic assignation. Identical twins Maxine Wolfe Zirkle and Madaline Wolfe Litten show me a snapshot when I interview them at one of their homes in Quicksburg, Virginia, in 1993. Maxine and Madaline were 16 years old at the time the photo was taken, and their brother Billy Wolfe was 18. "This was the last time he was home, January 30th, 1945," Madeline says. Maybe it's Maxine who says it. For the life of me, when I listen to the tape, I don't know which one is talking, so in transcribing the tape I just alternate, it's the best I can do. "We didn't have any transportation, and we walked him to the Greyhound bus, up Route 11," Madaline continues, "and when he said goodbye to us he said, "So long, kids, and if I never see you again, goodbye." And he waved all the way down the road. "Going out that road, that mile," Maxine says, "he walked between us and there was snow on the ground, I'll never forget. And that snow laid for it seemed like weeks. And every day, when we went to school, we would walk in his tracks. That's how sentimental we were." Billy was assigned as a replacement in Company C of the 712th Tank Battalion on the first or second of March 1945, shortly before the battalion crossed the Moselle River for the second time. On 16 March 1945 the five tanks of Billy's platoon were called on to assist a company of the 90th Infantry Division that was taking heavy casualties in an engagement with elements of the 6th SS Mountain Division in the village of Pfaffenheck, Germany. In the ensuing battle the platoon lost two tanks with four crew members killed. One of those was Billy Wolfe. Three months later, following inquiries from Billy's family, several survivors of the battle made statements about what happened. One of them was written by Otha Martin, the gunner in another tank in the platoon. "8 June, 1945," Otha's statement begins. "I, Corporal Otha Martin, was a member of the Second Platoon of Company C, 712th Tank Battalion, when the platoon entered the town of Pfaffenheck, Germany, on the morning of 16 March, 1945. During the engagement with the enemy in the town, I saw the No. 2 tank of our platoon receive a hit by an antitank gun and saw the tank burst into flames. This tank was commanded by Sergeant Hayward, with Corporal Clingerman as gunner, Private Billy Wolfe as Cannoneer [loader], Private [Koon L.] Moy as assistant driver and T-4 [Wes] Harrell as driver. The tank continued to burn all that day, and during the burning all the ammunition exploded. The next morning, 17 March 1945, I went over to look into the tank. The interior of the tank was completely burned, and the exploding ammunition had turned the interior into a shambles. The only remains that I could see of Private Wolfe were what looked to be three rib bones, and these were burned so completely that upon touching them they turned to ashes. Staff S. Otha A. Martin."

Over the years, I've interviewed a number of brothers, sisters and widows of men who were killed in World War II. The individual stories vary, but there is one constant: that a death in combat doesn't end with a rifle in the ground. Although Billy Wolfe was eventually declared killed in actions, his remains were never found, and his mother continued to write notes to him and hide them. Newell Brainard's mother eventually committed suicide. Don McCoy's mother joined the support group Gold Star Mothers. When she told the group she was going to France to see her son's grave in the American cemetery at St. Avold, another Gold Star mother said she would never be able to go to France and would Don's mother place some flowers at her son's grave as well. "Now if you're gonna cry now just you wait," Erlyn said as she related the story. I love that spot in the tape of our interview. It illustrates how even the saddest of moments can be tinged with humor. "There are thousands and thousands of those white crosses at St. Avold," Erlyn said. The cemetery guide left Major McCoy's mother at his grave, gave her a whistle and told her to blow it when she was ready to leave. Awhile later she blew the whistle and the guide returned. She showed him the number of the other Gold Star mother's son's grave. The tour guide pointed out that it was right across the walkway from her own son's grave. "And she was able to tell the other mother and your son and my son are neighbors."

One of the drawbacks of analog recording as that on a 60- or 90-minute cassette, the side may run out at the most inappropriate moment. In the few seconds it takes to flip the tape and hit the record button, valuable information can be lost. Thus at least a few words from my interview with the Wolfe twins are missing from the part in which they read some of the notes their mother penned to Billy after his death. Nevertheless ...

"In loving memory of my dear son who lost his life fighting for his country..."

end of side

"...but it only fills my heart with pain, for while others' hearts will sing with joy, mine will mourn for my dear boy. He died for his country, his life he gave, his dear body is sleeping in a lonely grave. Dear God up in heaven, send your angels I pray, to watch over his grave on Christmas day. God bless our dear boys who are still in lands far away, who cannot be with us on this Christmas day. Speak peace to their dear hearts and remove all their pain, and bring them home safely before Christmas again."I'm working on a new audiobook featuring interviews with brothers, sisters and widows of young men killed in World War II. I still have some editing to do, but it should be ready in the next couple of weeks. I hope you'll watch for it. It will feature interviews with:

James Bynum, younger brother of Quentin "Pine Valley" Bynum, 712th Tank Battalion.

Erlyn Jensen, kid sister of Major Don McCoy, 445th Bomb Group.

Sarah Schaen Naugher, widow of Capt. Jim Schaen, 445th Bomb Group.

Myron Kiballa, younger brother of Gerald Kiballa, 712th Tank Battalion.

Maxine and Madaline Wolfe, sisters of Billy Wolfe, 712th Tank Battalion.

Kay Brainard Hutchins, sister of Newell Brainard, 445th Bomb Group.

Elizabeth "Libby" Pitner, widow of Lt. Wallace Lippincott, 712th Tank Battalion.

Please email me if you'd like to reserve a copy when it's ready. Thank you, Aaron Elson

- - -

Published on July 20, 2017 11:00

July 4, 2017

Real names, real places

Robert Hopkins

Robert HopkinsA couple of weeks ago I was listening to "Fresh Air" on National Public Radio. Substitute host Dave Davies was interviewing Mark Bowden, the author of "Black Hawk Down," about his new book, "Hue 1968."

Hue is the city at the center of the action in Stanley Kubrick's "Full Metal Jacket." I was going to post a YouTube video of a scene from it, but I can't even watch it without grimacing, so I won't subject my handful of readers to it.

During the interview, Bowden read a passage. It's a gripping passage describing a scene I've heard variations of in my interviews with World War II veterans.

It also contains an error, the kind an author with all the resources at his disposal of a Mark Bowden shouldn't make. If I can confirm the error with a few clicks of a mouse, you'd think Bowden would have been able to, especially if it's in a passage he's going to read in interviews and cite as one of the key moments in the book.

Maybe the error shouldn't bother me -- after all, Steven Ambrose was famous for some of his miscues and Cornelius Ryan gave the world the impression that the D-Day assault on Pointe du Hoc was for naught. The reason this error bothers me is that Bowden is talking about people with real names from real places with real families who may or may not have known how their loved ones died, or what was or wasn't in the casket that came home.

This is the passage. At first I didn't sense an error. But being a newspaperman at heart, I'm always looking for a story angle, and for a moment I thought I found one.

"

Dave Davies: Well, Mark Bowden, welcome back to FRESH AIR. I want to begin with a reading of your book. This is a moment where we meet an American soldier who is with a unit that is pinned down by North Vietnamese soldiers. He's in a foxhole. Do you want to just set this up and read us this portion?

MARK BOWDEN: Yeah. His name is Carl DiLeo, and he was an infantryman with an Army Cavalry unit that had been sent out to push toward the Citadel from the north. And they got trapped in the middle of a field where they were stuck for a day or two essentially with the North Vietnamese taking target practice at them. And it was a - they lost half of their men. So it was a harrowing and terrifying experience for him and for all of the men who were there.

(Reading) The worst thing was the mortars, which rained straight down on them. They were being launched periodically from only a few hundred yards away. DiLeo could hear the pock and then the whoosh of its climbing. If he looked up, he could actually see the thing as it slowed to its apogee. From that point on, it was perfectly silent. There it would hang, a black spot in the gray sky, for what seemed like a very long beat, the way a punted football was captured in slow motion by NFL Films, before it plummeted straight down at them.

(Reading) The explosion was like a body blow even when it wasn't close. All of these were close. You opened your mouth, and sometimes you screamed out of fear, and it kept your eardrums from bursting. It was hell, a death lottery where all you could do was wait your turn. If you stayed down in the hole, you were OK unless the mortar had your number and landed right on top of you.

(Reading) This is what happened to DiLeo's good friend Walt Loos and the other man in his foxhole, Russell Kephart. They were one hole over. They got plumed. They were erased from the Earth. DiLeo watched the round all the way down, and it exploded right in their hole, vaporizing them. One second, they were there, living and breathing and thinking and maybe swearing or even praying just like him.

(Reading) And in the next second, two hale young men, both of them sergeants in the United States Army, pride of their hometowns - Perryville, Mo., and Willimantic, Conn., respectively - had been turned into a plume of fine pink mist, tiny bits of blood, bone, tissue, flesh and brain that rose and drifted and settled over everyone and everything nearby. It, or they, drifted down on DiLeo, who reached up to wipe the bloody ooze from his eyes and saw that his arms and the rest of him were coated, too. Then there would come another pock and another whoosh.

DAVIES: And that is Mark Bowden reading from his new book about a pivotal battle in the Vietnam War, "Hue 1968." You know, that's such a vivid description of the brutality and terror of war.This is where my ears perked up. I work part time for a small newspaper in Connecticut. The newspaper's parent company, Central CT Communications, recently bought the Willimantic Chronicle. I thought hey, Russell Kephart might still have family living in Willimantic and the fact that his death is described so powerfully in a bestseller might make for a good story.

Thanks to things like the Traveling Wall and various other sites, there is a good deal of information on the Internet about the 58,000 young Americans who died in the Vietnam War.

According to HonorStates.org, Thomas Walter Loos died "through hostile action ... small arms fire." So far so good, except for the difference between being killed by small arms fire and taking a direct hit from a mortar in your foxhole. Loos also was awarded the Silver Star.

Now imagine my shock when I looked up Russell Kephart and found at the Virtual Vietnam Wall (vvmf.org) that his place of birth was not Willimantic, Connecticut, but Lewistown, Pennsylvania.

There was a third sergeant killed from the same unit that day, Robert E. Hopkins. He was from Willimantic.

In the fog of war it might be easy for a combat veteran to mix up the hometowns, if that is what happened. But if a researcher or Bowden himself were responsible for the mixup, it would be unconscionable.

I sent a correction to "Fresh Air," but since it was the author's mistake and not the show's, they apparently didn't see fit to make a correction, although they did point out that they misidentified a war correspondent in a clip they aired at the beginning of the show.

In the last few days I've heard from the granddaughter of a person I interviewed some 20 years ago and was able to send her some anecdotal material about her grandfather, as well as the audio of the interview with her grandmother. And I heard from a young woman with the same last name as Max Lutcavish who is trying to determine if she was related. I sent her a couple of stories about Max, including one in which he told his buddy Dess Tibbitts he was going to go on a "careful drunk," mixing sterno with grapefruit juice, and a half hour later he couldn't stand up. Also, Lutcavish was responsible for one of the high water marks in the history of the 712th, knocking out a Mark V Panzer with the .37 millimeter gun of his light tank. No wonder his nickname was Lucky.

I'm not perfect. Years ago I posted on my web site a very convincing interview with a veteran who described in great detail how he survived a massacre, having his chin shot off when he turned his head as the German shot him in the head. Exhaustive research proved that such a massacre did not take place. That description got picked up in a book about Normandy, and will probably be rewritten in other books in future years. I believe the veteran had a form of Munchhausen syndrome, and was brilliant at making bizarre scenarios seem plausible. When I interviewed him the medic who treated him was there and I asked what he looked like. The medic said he looked like Chester Gump, a popular cartoon figure who had no chin. The veteran said to the medic, "You know, only a little while after you left the dressing you put on fell off." To which the medic replied, "I didn't charge you much, did I?"

esident of the United States takes pride in presenting the Silver Star Medal (Posthumously) to Thomas W. Loos, Sergeant, United States Army, for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action against a hostile force in the Republic of Vietnam. Sergeant Loos distinguished himself by intrepid actions on 4 February 1968 while serving with Company D, 2d Battalion, 12th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division. His unquestionable valor in close combat is in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflects great credit upon himself, the 1st Cavalry Division, and the United States Army.

Published on July 04, 2017 18:43

June 30, 2017

"He was the best thief I had"

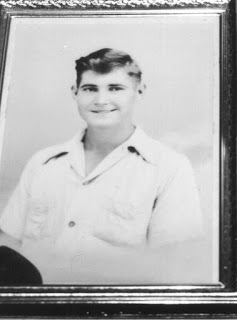

Forrest Dixon was the maintenance officer in the 712th Tank Bn.

Forrest Dixon was the maintenance officer in the 712th Tank Bn.It's funny the snippets of literature you read when you were young that stick with you for the rest of your life. The long, slow, brilliant opening of "The Grapes of Wrath," for instance, or the description in Emile Zola's "Germinal," in which a coal mining family makes coffee using the same coffee grounds five times. Maybe it was three times. I think of that when I pop a K-cup into the single serve coffee maker (actually, I make coffee the old fashioned way ... in a four-cup Mister Coffee carafe).

Last November I wrote a blog post about the critically acclaimed documentary "Blood on the Mountain," which my nephew Jordan Freeman co-directed, about coal miners, and I added the transcript I did of my impromptu 1996 interview with Eleanor Mazure, whose late husband, Frank Mazure, was a maintenance sergeant in Service Company of the 712th Tank Battalion. Eleanor grew up in Piney Fork, Ohio, which I think she said was about 20 miles north of Steubenville. Incidentally, Steubenville was recently mentioned in the news. The commentator remarked that while Steubenville is in the heart of coal mining country, coal mining is no longer its main employer. A hospital is. And that hospital will likely lose jobs if the Affordable Care Act is repealed. But I digress.

Two weeks ago I received an email from a young woman in Ohio. "Hi, Aaron," the email begins.

I never met Frank Mazure, this woman's grandfather, but his name came up in some of my interviews with veterans of the 712th Tank Battalion, with which my father served. He was spoken of very highly, so I located a few passages in which Sergeant Mazure was mentioned and sent them along in a followup email. One of them was this excerpt from an interview with Forrest Dixon, the battalion maintenance officer, probably in the late 1990s.

I saw your blog entry from last year about your nephew's documentary "Blood on the Mountain" and your interview with Eleanor Mazure. She was my grandmother. I am the oldest daughter of the son you referred to as Frank Junior.

I know very little about my father's side of the family because he wasn't around much after my parents were divorced. The interview was very enlightening! It gave me a mental picture of my grandmother and grandfather that I didn't have before. Reading it was a somewhat emotional experience for me. Thank you for posting it!

I noticed some references to the interview being recorded. Is there any way I could get a copy of that recording? It would be wonderful to hear my grandmother's voice as she talks about that part of her life. My son never met my grandmother, so I think it would be valuable to him to hear the interview as well.

Again, thank you so much for posting the interview and the photograph. I don't have much knowledge or memorabilia from that side of my family and I will definitely add this to it. Please let me know about the recording and let me know if there is anything else you may have that pertains to my family that you could share.

Aaron Elson:What was it you told Mrs. Mazure about her husband?

Forrest Dixon:He was the best thief I had. I said to her, "I don't mean it quite that way, but he got spark plugs that we badly needed, which was much above t.o. [table of operations]" And I said "That's why our tank battalion had one of the best records of any tank battalion in Europe, separate tank battalion." The number of tanks that we had operating, we had one of the best records. Colonel Randolph told me we had the best record. At one of the meetings that Randolph was to, I don't know what general was asking how many tanks he had operational, he said all we've got are operational, as far as he knew. And then the general pushed him a little bit, and Colonel Randolph says A Company has so many tanks, and B Company and C Company. But he said the difference between the number we're supposed to have and that number isn't because they're sidelined, it's because we've lost them and they haven't been replaced. And the guy quit bugging him. And I later found out that the fellow was bugging Randolph to find out the number because he had a battalion that just didn't have very many tanks ever.

We had, in most cases, if a company had ten tanks, they had ten operating. They might be back at my place for a few hours, but we had very few tanks non-operating. And what was knocking the tanks out was plugs, but we'd get 'em plugs right quick. I didn't dare give the companies, I didn't dare divide my number up, so we kept them, and we gave them, like if they had two tanks the plugs were going bad, we gave them, I guess there's two plugs per piston and what the hell did we have, nine pistons, I'd give them 36 plugs. And then I'd tell them to be back tomorrow with the old plugs. And then Mazure would take those and they'd clean them. We used them to get new plugs, and we kept the tank battalion running. That's about the whole thing that knocked out these tanks was running idle. But you couldn't tell them not to run them idle, good God, they had to move sometimes. They didn't have time to start the tank. They had to put it in gear and get the hell out of there. So we just had to live with it. I said "But we had enough extra plugs so we could supply 'em".

Aaron Elson: What did you say to Colonel Randolph on the third day in combat?

Forrest Dixon:The second day. He called me up about midnight, and he said, "How many tanks have we got?" I said, "We've lost half of them. We're good for one more day."

"No," he said. "We lost half of what we started with today. Tomorrow if we lose half of what we have left, and if the next day we lose half of those, we're good for several days." [Colonel George B. Randolph, the battalion commander, was a math teacher in Montgomery, Alabama, in civilian life].

"But," he said, "how many of them are battle casualties?"

And I told him, "We'll have most of those tanks back in operation in another 24 hours."

Part of our problem was just getting them out of the mud, or getting them hanging up on a hedge. Or replacing a section of track. And that we could replace.

I had a good crew. Sergeant Mazure had two crews, and each one could replace a motor in three and a half hours.

You see, one of the big jobs was to unbutton the armor plate. But we could do the whole thing in three and a half hours.

Aaron Elson:What would you replace them with, new motors or rebuilt?

This brought the following reply from Frank and Eleanor Mazure's granddaughter:

Forrest Dixon:In the early part of the war they were brand new ones. They called them Series 13 motors. Everything was on them. Carburetors and everything. A Series 13 motor, all you had to do was take the old motor out, put the new one in and hook it up.

By mistake we got a Series 11 motor I guess it was and good God, that's a 24-hour job. The carburetion and everything is off. You had to take this off and that off. But the Series 13, it's just like when you buy a motor for your car. Whether you buy a big motor or you could buy a short block. And every once in a while there'd be a package of cigarettes in the box the motor came in. Somebody back in the States would put a package of cigarettes in.

Wow! I really don't know what to say. Reading your reply brought an unexpected flood of emotions and I don't really know why. I think a gap that I didn't know existed is being filled for the first time in decades.I have since sent the young woman the audio of her grandmother's interview. My own maternal grandmother was a major part of my childhood, but I never knew my paternal grandmother, although a cousin of mine wrote a play about her, and I've seen a photo of her. And while I didn't have a similar flood of emotion upon finding the New York Times obituary of my great-great-grandfather, Meyer London, on the Internet, I did feel a swelling of pride at learning he was known as the Matzo King of New York.

One thing I've learned about oral history is that the stories are about real people with real names and in some cases valid addresses. The story of Frank and Eleanor Mazure is an example of the upside of this phenomenon. In my next blog post, I'll write about the downside.

The original post about Eleanor Mazure: "Coal Miner's Daughter"

The first chapter of "The Grapes of Wrath"

Published on June 30, 2017 06:19

May 27, 2017

Gold Star sisters, Part 1

Maxine Wolfe Zirkle and Madeline Wolfe Litten, 1993 A death in combat does not end with a rifle in the ground. Back home there are brothers, sisters, mothers, fathers, in many cases even sons and daughters, as the American War Orphans Network can so eloquently testify. And those lives are almost always changed forever.