Chris Gavaler's Blog, page 48

May 22, 2017

How Violent Are Superheroes?

When I ask my students to describe superheroes, they typically call out adjectives like “strong” and “handsome” and “moral.” I usually have the chalkboard covered before someone get around to “violent.” But violence is arguably the most defining quality of the genre.

Beginning with Detective Comics #33 and continuing with Batman #1, DC regularized Batman episode lengths to a Golden Age norm of twelve to thirteen pages. Of those first seven episodes, combat occurs on an average of seven pages—or roughly half of each episode. Beginning with Amazing Spider-Man #3, Marvel regularized Spider-Man’s episodes to a 1960s norm of an issue-length twenty-one or twenty-two pages. Averaging issues #3-9, combat occurs on eleven pages—or again roughly half of each episode.

If superhero comics draw from ancient myth, they are not mini-odysseys but mini-Trojan wars. Since 1939, Superman has waged “his never-ceasing war on injustices,” and Bruce Wayne has spent his life “warring on all criminals.” Their initial battles against a human criminal class expand to wider conflicts against fellow superhumans in which superheroes, ostensibly motivated to protect society, appear to relish combat itself. When first facing the Joker, Batman declares: “It seems I’ve at last met a foe that can give a good fight!” And Spider-Man laments two decades later: “It’s almost too easy! I’ve run out of enemies who can give me any real opposition! I’m too powerful for any foe! I almost wish for an opponent who’d give me a run for my money!” Comics often fulfill this wish by pitting superhero against superhero, a trope Alan Moore parodies in Watchmen when an interviewer asks Ozymandias about the Comedian:

NOVA: I heard that he beat you in combat, back when you were just starting out …

VEIDT: Yes, well, that was a case of mistaken identity and general misunderstanding. For some reason it happens a lot when costumed crime-fighters meet for the first time. (Laughter)

Mark Waid and Alex Ross extend the theme to its logical extremes in Kingdom Come, which is filled not with “heroes”, but rather

their children and grandchildren. […] progeny of the past, inspired by the legends of those who came before … if not the morals. They no longer fight for the right. They fight simply to fight, their only foes each other. The superhumans boast they’ve all but eliminated the super-villains of yesteryear. Small comfort. They move freely through the streets…through the world. They are challenged … but unopposed. They are, after all … our protectors.

Ross expresses the warriors’ joy of combat through the near-photorealistic grin of a downed superhuman and the maudlin tears of a human child fleeing falling rubble. The photo-like yet somehow still-bloodless renderings also reveal the core contradiction of superhero comics: the simultaneous celebration and avoidance of violence.

While superheroes may evoke ancient epic traditions, their paradoxical approach to violence may place them in a more specific sub-category, what my colleague Edward Adams terms the “liberal epic”: “a revivified heroic tradition” that glorifies “war and violence in the cause of liberty” (22). Adams identifies

two distinctive features of all liberal epics: first, an apologetic strategy for justifying this war as a worthy exception to a general rule […]; second, a concerted effort to limit or sanitize the public’s access to graphic representations of the liberating soldier-heroes’ acts of violence and domination—an effort, moreover, that has foregrounded a concern not to shock. (5)

Although too recent to be termed “universal,” the liberal epic is both multi-national and centuries-long, beginning with the French archbishop Fénelon’s Homer-inspired yet war-critical The Adventures of Telemachus in 1699 and Alexander Pope’s 1715 The Iliad of Homer. Where Homer presents combat in graphic and arguably glorifying detail, Adams argues that Pope’s “concision in translating Homer’s violence,” “his implicit omission of the nonpoetic material reality of Homer’s battle scenes,” and his preference for “more distanced and generalizing heroic couplets” and “poetic verbal analogy” “betrays his fundamental objection to epic” (75).

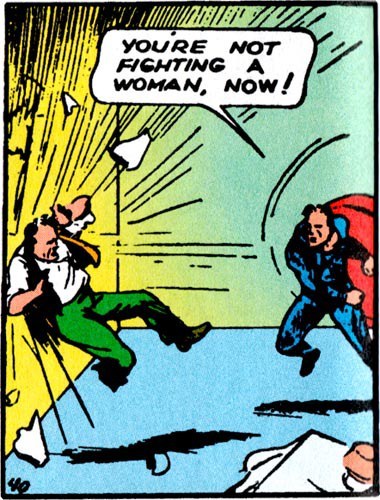

The superhero genre shares both the objection to and the extended focus on violence. Where liberal epic employs poetic diction to obscure its subject matter, comics achieve similar effects through visual devices. To stop a “blood thirsty aviator” in Action Comics #2, Superman leaps in front of a plane; Shuster draws the plane plummeting out of the frame, but instead of its impact and the death of the pilot, the next panel features another character who “witnessed the crash.” Batman kills his first adversary on the third page of his first adventure, sending a “burly criminal flying” from the roof a two-story house. Bob Kane does not draw the presumably fatal impact but does include the criminal’s barely discernible body on the sidewalk two panels later.

Though most superhero violence is non-lethal, even the broken noses and bloodied lips that would result from real-world punches often go undepicted. The 1966 Batman TV series parodied the comic book norm of sanitized violence by replacing live-action punches with cut-away shots of drawn sound effects such as “POW!!” and “BOFF!!” The stylization literally blocks its own content. Despite the TV parody, superheroes comics maintained the approach. In Green Lantern Co-Staring Green Arrow #77, Neal Adams draws soldiers charging across a mine field and then in the next panel entirely obscures their bodies with a bloodless “BLAM” below the caption, “Some die immediately.” For Wolverine #4, Frank Miller depicts the death of a Japanese crime lord through framing and closure effects. In the penultimate panel of the combat sequence, Wolverine’s claws are sheathed and his fist hovers in front of the warrior’s face; the final panel frames Wolverine’s face, partially cropped arm, and the letters “SNIKT,” the signature sound effect of his extending claws. Miller does not draw the claws piercing the enemy’s head.

Like the liberal epics of Dryden, Byron, Scott, Hayden, and Churchill, which according to Adams “implicitly admit to a deep human pleasure to dominating others—a delight at the surface of Homer—and address the need to control that pleasure” (12), superhero comics began as an oxymoronic genre of sanitized hyperviolence, pleasing young readers by avoiding direct representations of its most central subject matter.

May 15, 2017

Super LGBTQ in the 80s

The 1980s are often recalled as the conservative Reagan years. But they were also a tipping point in the superheroic battle for gay rights. LGBTQ characters in comics began the decade as villains and ended it with a revised Comics Code that championed their “orientation.”

Although England’s Wolfenden Commission recommended decriminalizing homosexuality in 1957, and the American Law Institute made a similar recommendation in 1962, the 1971 Comics Code update remained unchanged from its 1950s version. “Sexual abnormalities” were still “unacceptable” and “the protection of the children and family life” paramount—even after the American Psychiatric Association struck homosexuality from its mental disorder list in 1973. As a result, superhero comics avoided gay characters until the 1980s, and early depictions cast them as villains.

Beginning in Peter Parker, The Spectacular Spider-Man #43, Roger Stern scripted Roderick Kingsley as a thin, limp-wristed, ascot-wearing fashion designer who another characters calls a “flaming simp!” and who is later revealed to be the supervillain Hobgoblin (1980).

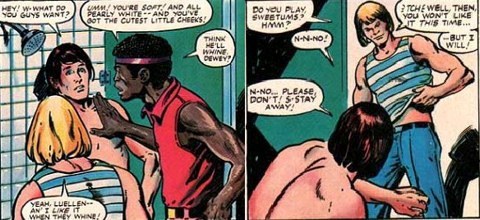

Kingsley is not directly identified as gay, but the same year in the non-Code Hulk Magazine #23, Jim Shooter and Roger Stern scripted two men, one black and one white, attempting to rape Bruce Banner, who escapes a YMCA shower room by threatening to transform into the Hulk: “You hurt me and I’ll get big and green and tear your … head off!”

Alan Moore and John Totleben recreate a similar scene eight years later in Miracleman #14 when three teens succeed in raping the pubescent Johnny Bates: “You love it. You littul poof. Say you love it.” He escapes by actually transforming into the monstrous Kid Miracleman, who then massacres thousands of Londoners before being forced to transform back, leading Miracleman to murder Johnny to prevent future massacres—all the results of a homosexual rape.

Early depictions of transgender characters are comparatively positive. Because a character’s consciousness is often depicted as existing independently of the character’s body, superhero comics provide a range of opportunities for fantastical gender-switching. In 1975, writer Steve Gerber introduced Starhawk, a male superhero who exchanges bodies with his female lover, Aleta. Jim Shooter scripted Starhawk in The Avengers #168: “Aleta gestures in defiance as her persona submerges, giving way – as the persona of Starhawk assumes command, the corporeal form they share shimmers… changes.” Although both characters are heterosexual and cisgender, the visual depiction of a woman transforming into a male superhero alters the male-to-male norm established in Action Comics #1.

Mike W. Barra and Brian Bolland’s 1982 Camelot 3000 introduced a more overtly transgender superhero, the legendary knight Sir Tristan reincarnated into a woman’s body. Tristan rejects a female sex identity until the maxi-series’ conclusion when he chooses to live as a woman with his reincarnated female lover Isolde.

Beginning in the 1987 Alpha Flight #45, Bill Mantlo scripted a more convoluted, multiple body-swapping plot that concluded with the spirit of a previously deceased male character, Walter Langkowski, inside a formerly deceased female body—except when Langkowski transforms into the male body of the Hulk-like Sasquatch for superheroic adventures. Like Sir Tristan, Langkowski, taking the first name “Wanda,” continued a previous romantic relationship with his female lover.

While challenging gender binaries, these early depictions of transgender and gay superheroes also maintain aspects of traditional masculinity and heterosexuality. The female Aleta transforming into the male Starhawk literalizes the emasculated or female-like nature of Clark Kent already implicit in the formula. With Tristan and Langkowski, a female body is controlled by a male consciousness, and the male consciousness is male by virtue of having existed previously in a male body. The physicality of the male body, even when not currently present, is primary. Tristan and Langkowski also treat transgender as a temporary plot conflict resolved by a male consciousness accepting a female sex identity through what visually appears to be a lesbian romance, normalizing same-sex female relationships as fantastical expressions of heterosexuality. None of the narratives present a female consciousness inhabiting a male body or male bodies in sexual relationships. Since only female homosexuality is visually portrayed and because early depictions of gay men are villainous, superhero masculinity remained heterosexual and homophobic.

John Byrne challenged that norm in 1983 with Alpha Flight superhero Northstar. Because the Code barred openly gay characters, Byrne suggested the character’s sexuality indirectly, for example, introducing his friend Raymonde Belmonde whom Byrne draws in a nearly identical light blue suit and red ascot that Mike Zeck designed for Roderick Kingsley four years earlier. Byrne was either alluding to Zeck or both were drawing on the same cultural stereotype—arguably the blue suit worn by an emaciated David Bowie on the album cover of the 1974 David Live.

Despite more direct portrayals of same-sex superhero relationships in non-Code-approved issues of The Defenders and Vigilante in 1984, Bill Mantlo continued the pattern of indirection when scripting Alpha Flight in 1985. When he began a 1987 story arc in which Northstar contracts AIDS, Marvel under the editorship of Jim Shooter altered the disease to a fantastical ailment, forcing the character into temporary retirement. Other writers followed a similar approach, including gay characters while avoiding identifying their sexualities overtly. Scripter Al Milgrom in the 1988 Marvel Fanfare #40 moved closer to confirming the relationship between mutants Mystique and Destiny originally intended and implied by Chris Claremont in 1981.

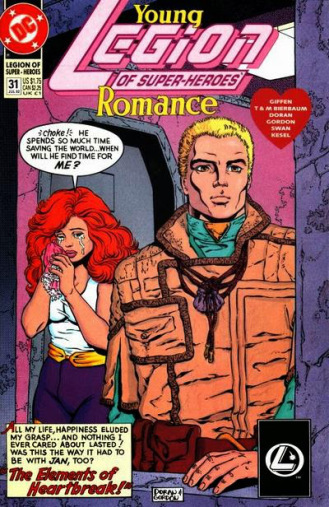

Paul Levitz, during his 63-issue, 1984-89 run of DC’s Legion of Super-Heroes, also indirectly indicated that the 60s characters Lightning Lass and Shrinking Violet were lesbian lovers, a subplot continued by the next team of writers in 1989. Alan Moore’s 1986 Watchmen memoirist Hollis Mason alludes to two gay superheroes, Hooded Justice and the Silhouette, both of whom may have been murdered for their sexualities.

DC’s Steve Englehart and Joe Stanton’s 1988-9 The New Guardians featured the flamboyantly effeminate Extrano, who wore a large golden earring and a purple cape but was never explicitly identified as gay. John Byrne also introduced police captain Maggie Sawyer to Superman in 1987, interrupting Superman mid-sentence before he could explicitly identify her as lesbian.

The increase in gay representation parallels gains of the gay rights movement of the 80s. Wisconsin, for example, became the first state to outlaw discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in 1982, and 600,000 protesters marched in Washington in support of gay rights in 1987. “After decades existing in a subtextual closet of metaphors, tropes, and stereotypes,” writes Sean Guynes, “in 1988 openly gay characters exploded in the pages of superhero comics” (2016: 182). When the Comics Code Authority revised its guidelines in 1989, it reversed its quarter century of anti-gay mandates. The Code’s new “Characterizations” subsection required creators to “show sensitivity to national, ethnic, religious, sexual, political and socioeconomic orientations.” The revision also acknowledged that heroes “should reflect the prevailing social attitudes,” potentially allowing positive portrayals of openly gay superheroes.

As a result, LGBTQ characters transformed radically in the 90s. That happier history is here.

May 8, 2017

Political Superhero Team-up: Super Goat Man and Passivityman!

I know, you never heard of either. But this dynamic duo reveals more about the politics of superheroes than do the contents of most comic shops. Jonathan Lethem’s short story “Super Goat Man” appeared in The New Yorker in April 2004, and Deborah Eisenberg (also a New Yorker fav) published “Twilight of the Superheroes” that fall.

Why were literary Avengers assembling in 2004? I’ll get back to that. First a recap:

I was born in 1966, Lethem a little earlier, his narrator Everett a little before that—not the start of the Silver Age, but the start of its relevancy. Everett’s birth also parallels the escalation of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Like me, Super Goat Man and his narrator became professors in “the harmless pantheon of academia.” Everett ends his tale on the job market. If I’m doing the math right, that’s 1993, same year my wife landed her current academic position. Everett is postdocing at Rutgers, where my wife and I met as undergrads. We married in 1993, same as Everett and his wife, a fellow medievalist.

Similarities end there, since, to the best of my knowledge, neither my wife nor I ever had sex with Super Goat Man.

Lethem offers no explanation for Super Goat Man’s fantastical leap (“fall from grace,” Everett calls it) from comic book pages to real world Brooklyn where Everett first indifferently meets him. He was “at best a minor star” in a small publisher’s five-issue run that Everett finds “embarrassing.” In the flesh he’s just a guy in a sleeveless undershirt who happened to have “two little fleshy horns on his forehead.” When he says, “I lost my job” for “being too outspoken about the war,” he means his superhero job, not his alter ego’s college position, which he quit after Kennedy was shot. How that relates to his “ludicrous and boring” adventures rescuing cats and old ladies in comics, Lethem doesn’t explain.

Everett and the other kids prefer “superheroes in two dimensions,” but their dads are entranced because Super Goat Man “represented some lost possibility in their own lives.” That possibility is never realized though. When next seen, Super Goat Man is goaded by college students to display his superpowers, but when he’s unable to catch a falling drunk with his prehensile toes, the kid ends up paralyzed.

“Had the hero,” asks Everett, “failed the crisis? Caused it, by innate provocation? Or was the bogus crisis unworthy, and the outcome its own reward? Who’d shamed whom?”

As a drawing Super Goat Man was “amateurish, cut-rate, antiquated,” but in his final appearance, he’s worse, “reduced to a kind of honorary position” as “a campus mascot.” He’s “quite infirm” due to his “accelerated aging process,” a result of the “sacrifice he’d made, enunciating his political views so long ago.” He has literally “shrunk,” not “five feet tall” now, and sometimes drops “to all fours” and shakes himself “like a wet dog,” unaware of his “sacrificed dignity.” He declares in his “sepulchral” voice: “All this controversy . . . not worth it,” meaning “his lost career.” But Everett’s “loathing” is directed at his own father’s “susceptibility to the notion of a hero.”

If all that doesn’t sound very superheroic, wait till you meet Deborah Eisenberg’s Passivityman.

I took a couple of MFA classes from Eisenberg just as her collection Twilight of the Superheroes was published in 2006. Because the title track had been rejected by The New Yorker and its ilk, Eisenberg’s boyfriend (that’s her term) Wallace Shaun created Final Edition, a literary one-off, to spotlight the short story rather than release it to shallower literary waters (where I do most of my own submission fishing).

Eisenberg’s superhero is the creation of Nathaniel, a twentysomething slacker facing his and his friends’ imminent expulsion from their ritzy, Manhattan sublet. When Nathaniel started Passivityman in junior high, he battled Captain Corporation in “a comic strip that ran in free papers all over parts of the Mid-west, a comic strip that was doted on by whole dozens . . . of stoned undergrads.” Nowadays, Nathaniel’s friends uncomfortably notice, the hero has become “intellectually passive,” even “passive-aggressive,” more like “his morally neutral, transgendering twin, Ambiguityperson.” Passivityman, like Nathaniel and his dispersing friends, is “losing his superpowers.”

Though the team’s “holding pattern” may have something to do with “the eternal, poignant weariness of youth,” the more immediate problem is 9/11. They were all out there on the terrace when the towers came down. Nathaniel keeps “waiting for that shattering day to unhappen, so that the real—the intended—future, the one that had been implied by the past, could unfold.” Meanwhile, his superhero’s rallying cry, “No way,” morphs into “Whatever,” until Nathaniel has “all but stopped trying to work on Passsivityman.”

When I interviewed Eisenberg for an article in U.Va’s alumni magazine, she credited Wallace (she actually calls him “Wall” and carries a Star Trek: Deep Space Nine trading card of him as the Grand Nagus of the Ferengi Alliance) with starting her writing career. He was also “incensed when the three highest-profile magazines rejected” her “Twilight of the Superheroes.” And thus was born Final Edition, a political magazine by writers “who seriously believe that part of our national problem is that the people who run the country have a crude and minimal imaginative life.”

In addition to Eisenberg’s short story, Shaun included Jonathan Schell’s essay “Invitation to a Degraded World.” Since 9/11, it seemed to Schell, “history was being authored by a third-rate writer rather than a master, or was being compelled, even as it visited increasing suffering on real people, to follow the plot of a bad comic book,” in part because of the tone-setting “appearance of Osama bin Laden, a mass murderer who came across at the same time as a comic-book, caricature villain.” Sadly, Bush accepted “Bin Laden’s invitation to enter into the world of an apocalyptic comic book,” dividing “every person and government on earth into two camps — the good, the lovers of freedom, who are ‘with us,’ and the ‘evil-doers’ who hate the good ones for their very goodness,” while turning “himself into a sort of real life action figure . . . on the deck of the USS Abraham Lincoln to declare success in the Iraq.” As a result, not only was “the quality of political discussion and decision-making” damaged but “the dignity of the real.”

And that gets us back to Super Goat Man. Everett knows two-dimensional heroes belong in a two-dimensional world. Lethem’s cut-rate hero enters our world via the fantastical conduit of 9/11 and its on-going sequel, The War of Terror, and as a result both he and America deteriorate. Superheroes follow a formula of goofy but absolute good vs. reassuringly simple evil. They can’t cope with the complexities of politics—either in protest of the Vietnam War or the implementation of counter-terrorism. Superheroes and the real world shame each other.

Passivityman can’t cope either. He needed the two-dimensional “curtain” that divided him from “the dark world that lay right behind it, of populations ruthlessly exploited, inflamed with hatred, and tired of waiting for change to happen by.” The curtain had been “painted with the map of the earth, its oceans and contents, with [his] delightful city.” And the 9/11 planes tore through it.

The opposite of a superhero isn’t a supervillain. When exposed to three-dimensional reality, superheroes transform into their true opposites: irredeemable failures.

The drift toward comic book simplicity continued after 2004–until the reality-leaping election of Donald Trump flattened the political landscape in a single bound. Now the failings of George Bush seem nostalgically complex. Trump drew himself as a two-dimensional fantasy for white male Republicans longing for an old-school hero. That’s why Everett’s “loathing” for Super Goat Man is really about his father’s “susceptibility to the notion of a hero” and the damage it does to “the dignity of the real.” A majority of Americans would like that “shattering day to unhappen,” but unlike Nathaniel, they haven’t morphed into Passivityman. They aren’t sitting around, waiting for “the real—the intended—future, the one that had been implied by the past” to return. They’re tearing open the curtain themselves.

[image error]

May 1, 2017

Super LGBTQ

Last month I looked at LGBTQ characters in the early comics years. There were very few. That changes in the 90s.

Publishing in DC’s non-Code Vertigo imprint, Neil Gaiman’s ongoing Sandman introduced comics’ first overt and non-fantastical trans characters in 1991, another “Wanda,” who Shawn McManus renders with awkwardly masculine features. Marston and Peters’ 1946 Blue Snowman, a female scientist who takes a male disguise, significantly precedes Wanda, but it is unclear to what degree the character identities as male. Since the early character is also a supervillain, Blue Snowman arguably supports gender binaries.

Within Code-approved comics, scripter William Messner-Loebs revealed the first openly gay character, the Pied Piper, in Flash #53. Flash asks whether the Joker is gay and the former 60s supervillain answers: “He’s a sadist and a psychopath … I doubt he has real feelings of any kind… He’s not gay, Wally. In fact, I can’t think of any super-villain who is … Well, except me of course” (Messner-Lobes & LaRocque 1991).

Marvel now allowed Scott Lobdell to script Northstar’s declaration in the 1992 Alpha Flight #106: “For while I am not inclined to discuss my sexuality with people for whom it is none of their business – I am gay!” (Lobdell & Pacella 1992). Mark Pacella’s cover features a close-up of Northstar’s shouting, eye-clenched face and the header: “NORTHSTAR AS YOU’VE NEVER KNOWN HIM BEFORE!” Pacella also renders him in the hyper-muscular style that was standard for male superheroes in the 90s. His costume, the same worn by all Alpha Flight members, is non-symmetrical and so metaphorically a rejection of simple binaries.

Four months later at DC, Legion of Super-Heroes writers Mary and Tom Bierbaum revealed that Element Lad’s long-time girlfriend had been born in a male body and was transforming it with the fantastical drug Profin. The two continue their previously heterosexual relationship now as male lovers: “it doesn’t matter,” says Element Lad, “You just have to understand – this is not what’s changed between us […] anything we shared physically … it was in spite of the Profin, not because of it!” (Bierbaum et al 1992). The relationship echoes Tristan and Isolde of a decade earlier, only now with a gender-fluid character accepting a male sex identity through the resolution of a same-sex male romance. Male homosexuality had entered superhero masculinity.

LGBTQ superheroes increased significantly in the following decade. In 1993, the year President Clinton signed “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” into military policy, Milestone Comics’ Blood Syndicate #1 introduced scripters Dwayne McDuffie and Ivan Velez, Jr’s Masquerade, a black trans man who assumes a male form as a shapeshifter. The same year, DC’s Vertigo published two limited series featuring gay superheroes as title characters: Grant Morrison and Steve Yeowell’s Sebastian O and Peter Milligan and Duncan Fegredo’s The Enigma, which included an image of a gay kiss and a full-page image of the naked lovers entwined in bed after sex: “two men redrawing the maps of themselves.” In 1994, David Peter scripted the Pantheon superhero Hector as gay in Incredible Hulk. In 1997, Supergirl featured the shapeshifter Comet who alternates between a female human identity and a male centaur. In 1998 James Robinson’s Starman #48 featured the title character kissing his boyfriend. Alan Moore included a trans woman incarnation of the female superhero Promethea in 1999. In 2001, Peter Milligan and Mike Allred’s X-Force #118 included a kiss between two male superheroes, and the following year in The Authority #29 Mark Millar and Gary Erskine married superheroes Apollo and Midnighter, whom creator Warren Ellis had established as openly gay in 1999. Writer Judd Winick introduced the openly gay character Terry Berg to Green Lantern in 2001, and the 2002 #154-5 “Hate Crime” plot portrays his brutal beating and Green Lantern’s near deadly retaliation—reversing the 1980 and 1988 portrayals of gay men as violent predators.

21st-century comics continued the expansion of LGBTQ representation, including John Constantine in Hellblazer (2002), Moondragon and Marlo Chandler-Jones in Captain Marvel (2002), Renee Montoya in Gotham Central (2003), Xavin and Karolina in Runaways (2003), Miss Masque in Terra Obscura (2003), the rebooted Rawhide Kid in Rawhide Kid: Slap Leather (2003), Hulking and Wiccan in Young Avengers (2005), Freedom Ring in Marvel Team-Up (2006), Erik Storn as Amazing Woman in Infinity Inc. (2007), Daken in Wolverine Origins (2007), Loki in Thor (2008), Kate Kane and Maggie Sawyer in Batwoman (2011), Bunker in Teen Titans (2011), Miss America Chavez in Vengeance (2011), Northstar’s marriage in Astonishing X-Men (2012), Alan Scott Green Lantern in Earth Two (2012), Hercules and Wolverine in X-Treme X-Men (2013), and Alysia Yeoh in Batgirl (2013). 2015 alone includes Iceman in Uncanny X-Men, Sera and Angela in Angela: Asgard’s Assassin, Catman in Secret Six, Alpha Centurian in Doomed, Harley Quinn and Poison Ivy in Harley Quinn, Batwoman in DC Comics Bombshells, and Catwoman. Probably the most prominent challenge to the superhero’s traditional gender binaries is Deadpool, who in the opening pages of the 2016 Spider-Man/Deadpool #1 “Isn’t it Bromantic?” Joe Kelly and Ed McGuiness depict in an explicitly sexual conversation with Spider-Man as the two are tied together and about to be killed by a demon horde as they hang upside down.

DEADPOOL: I have to tell you one last thing that is, in my humble opinion, the single most important thing you need to know in the whole universe right at this second … If you don’t stop squirming, I am totally going to “unsheathe my katana” all up against your “spider eggs.” And by “katana” I mean –

SPIDER-MAN: What is wrong with you?

DEADPOOL: What?! I’m a red-blooded Canadian male! It’s friction and junk-biology and spandex grinding on leather and just please stop wiggling your webbing –

SPIDER-MAN: Would you just shut up so I can think!

DEADPOOL: Don’t yell at me … that’s totally one of my turn-ons. (2016: 1-3).

The 2015 film Deadpool also alluded to the character’s pansexuality—a stark contrast to the contractual agreement between Sony and Marvel requiring that Peter Parker be “Caucasian and heterosexual” (Biddle). Finally, new Wonder Woman writer Greg Rucka stated in an interview that Wonder Woman’s home island “is a queer culture” and that Wonder Woman “has been in love and had relationships with other women,” facts he hopes to “show” rather than “tell” in future episodes (Santori-Griffith 2016).

Visually and narratively, however, LGBTQ superheroes are often little different from heterosexual, cisgender superheroes. “Though demarcated by an explicit declaration of their same-sex object choice,” writes Panuska, “it is often difficult to otherwise cordon … ‘gay’ superheroes from their heterosexual counterparts” because they still conform “to the traditions of a nearly 80-year-old genre” and so do not “stray from traditional associations” (2013: 25). While female and LGBTQ superheroes have significantly challenged the traditional superhero formula, Michael A. Chaney in the Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender still concludes that the genre affirms “the fantasy of a masculine universe” in which “the objectifying conventions of superhero illustration disrupt the very forays into progressive gender politics (cyborg sexuality, transgender, nongender, etc.) that superhero stories increasingly undertake” (2007).

John G. Cawalti, writing in 1976 while black superheroes embodied racist stereotypes and LGBTQ superheroes were non-existent, analyzed the relationship between formula literature, such as superhero comics, and the culture that produces it, arguing that such “stories affirm existing interests and attitudes by presenting an imaginary world that is aligned with these interests and attitudes” and so “help to maintain a culture’s ongoing consensus” by “confirming some strongly held conventional view” (1976: 35). The comic book superhero—white, male, heterosexual, cisgender, and non-disabled—has served this function since its conception. But, as Cawalti also argues, popular fiction formulas also “assist in the process of assimilating changes in values to traditional imaginative constructs” and so “ease the transition between old and new ways of expressing things and thus contribute to cultural continuity” (36). The comic book superhero, a continuous cultural construct since 1938, demonstrates this capacity by evolving in response to larger social attitudes, reflecting progressive shifts within conservative norms. The history of black and LGBTQ superheroes demonstrates that superhero comics are rarely agents of cultural change, but that once a social attitude has shifted, comics quickly follow and so reinforce the new status quo.

April 24, 2017

The Making of “Superheroes Decoded” (Or, How I Didn’t Meet George R. R. Martin Last Summer During the Shooting of a Superhero Documentary)

The History Channel is airing a two-part documentary Superheroes Decoded next Sunday and Monday, April 30 and May 1, at 9:00. It’s the first superhero documentary I know of since PBS produced Superhero: A Never-Ending Battle in 2013, which was basically a two-hour advertisement for the DC and Marvel film franchises. I apologized after showing it to my class and then listed the errors and misleading statements. I’m hopeful the History Channel has done significantly better.

According to their press release, superheroes “embody America’s deepest fears and greatest aspirations.” I agree—though in On the Origin of Superheroes I use slightly different adjectives: “our most nightmarish fears, our most utopian aspirations.” I have no idea what I said while on camera. Though the “interviews with dozens of experts” include me, who knows what if anything wound up in the final edit.

I started pretty low on the list, way way under George R. R. Martin—though his interview immediately preceded mine. He must have strolled past the open green room door while the make-up artist was brushing my eyelids. She also trimmed my eyebrows, which I admit have gotten surprisingly unruly in recent years. Worse, a cyst had spontaneously blossomed on my neck a couple of days before. They assured me it wasn’t visible on camera, which I seriously doubt. It felt like it was about to start talking and contradicting me—like the evil boil in How To Get Ahead in Advertising. Another reason to tune in next Sunday.

The documentary company flew me in from Virginia and put me up overnight in Manhattan. The film set was the fifth floor of a dilapidated warehouse in Brooklyn—the kind of location where thugs tie up their kidnap victims before someone in a cape swings through one of those open windows. I suspect it will make a great backdrop. Unfortunately, the ceiling was open to the sky in places and that corner of Brooklyn is apparently under a JFK flight path. We had to stop every time the sound tech picked up too much background noise on his headphones. The rumbling elevator didn’t help either.

I spent about two hours in the interview chair, with not quite a dozen people attending literally to my every move. The make-up artist swooped in every time my forehead glistened under the spotlights. The sound tech kept reaching into my shirt to adjust the remote mic or the cord snaking down to the antennae unit clipped to my belt. A larger mic on the end of a hand-held rod bobbed above my head. They used two cameras too. Another crew member paced back and forth, sliding one along a two-yard track. The other was stationary, and, to help interviewees speak directly into it while having a conversation with the director, they mirror-projected his face onto a see-through screen in front of the lens while he sat on a stool behind and to the side. Only then it looked like he had two faces—the second in his right armpit—so they jerry-rigged a curtain too.

The director said afterwards that I give good soundbites—though I knew they would have sounded moronically brief in any other interview situation. His voice won’t be in the film, which meant every time he asked me a question I had to include it in my answer. “How do superheroes compare to gods in ancient mythology?” “Superheroes are very different from the gods of ancient mythology.” By the end of the second hour, I was parroting gibberish. I assume they didn’t make an outtake reel, but if they did, my scholarly career could be in jeopardy.

He also complimented my lack of ums, but then said that didn’t matter since the two cameras allow them to edit them seamlessly out anyway. I’d paced for a half hour before hand, muttering calm, sensible sentences for the few questions I was expecting. I memorized what I could memorize and then just practiced speaking slowly and clearly and confidently and succinctly—and so like someone almost nothing like me. I’ll find out Sunday if it worked.

A good friend and fellow scholar interviewed right before George R. R. Martin, so we grabbed lunch before my interview. I was especially happy to see her since I’d recommended her to the documentary company when they’d asked about other “experts” to interview (and to be accurate, Carolyn’s Superwomen: Gender, Power, and Representation is the high mark in superhero gender analysis). Another good friend and fellow scholar, Pete Coogan, had done the same for me. I recognized the other experts on the interview list too, so another reason to have high hopes.

I apparently don’t wear make-up often enough, because my eyelid was infected the next morning. So I flew home with not one but two disturbingly visible growths. My other souvenirs were better: print-outs of the fan letters Martin wrote to Marvel Comics in the 60s and read on camera for the documentary. They were his first publications. I would excerpt a bit here, but I have no idea where I put them. June was a long long time ago.

Superheroes Decoded was originally slated for last November or December, and the two parts described to me were different from the two parts currently advertised, so I assume, to no surprise, all kinds of interesting things happened post-production. Maybe that includes a few, non-humiliating seconds of me.

April 17, 2017

My Morning Memes, part 7

We’ve survived another two weeks of Donald Trump’s Great American Dystopia. It feels like a TV show, the kind with a brutally self-serving tyrant and masses of mindless zombies, so the Walking Dead season finale gets a deserved nod this week. Mostly though it’s just more of the ongoing catalogue of breathtaking hypocrisy. Is there no criticism of Obama that Trump won’t both reverse and worsen as President? Vacation costs, record transparency, bombing Syria–the grotesque to the petty all horrifyingly merge, while the slow ticking of the Russian investigations continues. It took Watergate three years, from break-in to resignation, to unseat Nixon. I’m hopeful Trump will break that record. Meanwhile, enjoy the latest memes:

[image error]

Congressman Goodlatte got a break this round, but I did think my usually image-less Dear Bob blog deserved a commemorative illustration when I hit Email #125 earlier this month:

April 10, 2017

Super Queer: The Early Years

The superhero genre encodes a fear of crossing gender binaries. Neil Shyminsky argues that “the mainstream superhero narrative is often surprisingly conservative, aimed at legitimizing normative ideologies and containing that which threatens them,” including “anxiety that is endemic to the superhero’s identity and sexuality” and so threatens their “unproblematically hetero, masculine” appearance (2011: 288-290). Sarah Panuska concludes similarly: “Given the typification of heterosexuality through the superhero’s masculine privilege, heterosexuality exists as an assumption– an implication – of the genre” (2013: 25). Shyminksy is analyzing 21st-century films and Panuska gay superheroes in recent comics, but the U.S. cultural desire for absolute gender divisions applies even more to the origins of the genre.

Lewis M. Terman and Catharine Cox Miles write in their 1936 Sex and Personality: Studies in Masculinity and Femininity: “The belief is all but universal that men and women as contrasting groups display characteristic sex differences in their behavior and that these differences are so deep seated and pervasive as to lend distinctive character to the entire personality” (1936: 1). The rationale underpins the authors’ influential M-F Personality Test, including “an explicit recognition of the existence of individual variant forms: the effeminate man and the masculine woman . . . ranging from the slightly variant to the genuine invert who is capable of romantic attachment only to members of his or her own sex” (2-3). While Terman and Miles hoped “concepts of M-F types existing in our present culture be made more definite,” superhero comics defined and reinforced those same concepts through fiction (3).

By establishing a very particular hyper-muscular, able-bodied masculinity as an ideal, the male superhero body projects all other physical variations as inferior and so potentially antagonistic. “In the misogynistic, homophobic (and racist) view of this ideology,” writes Yann Roblou, “the despised Other that masculinity defines itself against conventionally includes not just women but also feminized individuals” (2012: 84). For Fighting American, notes Carter, “the mind is the strength of the evil other” who is variously “emasculated” and “through differing body constructions” is depicted as physically “dysfunctional, blemished, or otherwise misshapen” (364).

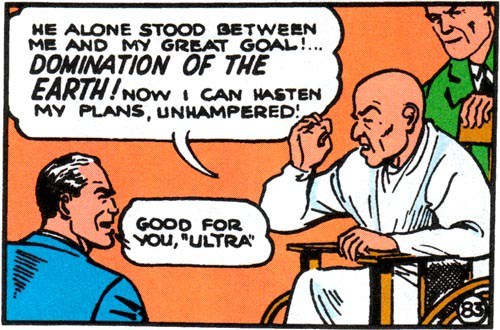

The trend is apparent as early as Action Comics #13, in which Siegel and Shuster introduce Superman’s first supervillain, the Ultra-Humanite, a balding, wheelchair-bound scientist who must rely on his henchmen to carry him from a burning building—in a pose that echoes Superman carrying Lois Lane from dangers in previous episodes (Siegel & Shuster 2006: 192). Beginning in 1931, Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy comic strip features an array of physically “blemished” villains—Pruneface, Flattop, Doc Humo—all supporting by contrast the hero’s masculinity. Finger and Kane continued the approach with Batman’s villains, including Joker and Clayface in 1940, Penguin in 1941, and Two-Face in 1942.

Marvel expanded the motif in the 60s with Doctor Doom’s scared face, the one-armed Dr. Connor’s transformation into the Lizard, the Kingpin’s visual obesity, the radiation-deformed bodies of the Gargoyle, Abomination, and the Leader, Baron Zemo’s skin-affixed mask, and the giant-headed M.O.D.O.K., who, writes Mike Conroy, plagued “Captain America, whose physical perfection he so resented” (2004: 253). Contemporary examples include the 2004 Punisher villain Finn Cooley, whose skinless face is enclosed in a transparent plastic mask, and the 2004 anti-mutant villain Ord, an alien whose face is mutilated during combat with the X-Men. Because of the contrasting structure of “superior and masculine” vs. “inferior and feminine,” each antagonist’s physical inferiority is itself emasculating and so self-defeating even prior to a superhero’s narrative domination. The superhero’s victory is visually a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The gender binary also equates “variant” men with women—a thematic implication first literalized by Siegel and Shuster in Action Comics #20 when the Ultra-Humanite transplants his “tremendous brain” into a movie actress’ “young, vital body” (Siegel & Shuster 2007: 316, 191). Though Superman concludes the story wondering, “Did Ultra escape? If so, will he continue his evil career?” (192), in the following issue, the narration switches pronouns to explain that Ultra “miraculously survived her last encounter,” and Superman refers to her now as a “madwoman” (Siegel & Shuster 2007a: 5, 7). The episode is rife with apparent sexual visual puns too, with Ultra first seducing a male scientist with her kitten and later falling into the yonic opening of a volcano’s crater. DC appears to have been troubled by a sexually fluid antagonist, because Luthor permanently replaces Ultra in the subsequent issue. Siegel and Shuster, however, only made the genre’s hyper-masculine binary logic explicit: not only is a partly paralyzed male body parallel to an ideally beautiful female body, a male genius is so feminized by his intellect that his sex identity is also female. Though the character’s sexuality is more ambiguous, the seduction of the scientist suggests that Ultra was what Terman and Miles term a so-called “genuine invert” even prior to the fantastical sex-change operation.

The superhero plot structure of physical domination, despite overtly expressing traditional gender values, may also encode a subtext of bisexuality. Male antagonists and female love interests share the same oppositional relationship to the male superhero, who expresses his masculinity and so his physical superiority by rescuing the weak female and by emasculating the weaker male. By dominating both, he places them in parallel gender positions, and since his relationship to the female love interest is overtly romantic, his relationship to a male supervillain may be read similarly.

Bisexuality is also paradoxically supported by heterosexual romances between male superheroes and female supervillains, suggesting an erotic subtext to all hero-villain relationships. Bill Finger and Bob Kane established the motif in the 1940 Batman #1 in which Batman allows Catwoman to escape after her debut appearance, musing: “Lovely girl! – what eyes! Say – mustn’t forget I’ve got a girl named Julie! Oh well… she still had lovely eyes! Maybe I’ll bump into her again sometime” (Kane et al 2006: 177). That flirtation evolved into an overt sexual relationship in Judd Winick and Guillem March’s 2011 Catwoman #1, which concludes with a multi-page sex scene. Typical superhero battle scenes feature two male bodies in equally close contact—a trope expanded into gay erotica in the 2007 short story collection Unmasked: Erotic Tales of Gay Superheroes.

Whether analyzed as gay, female, transgender, emasculated, feminine, intellectual, or disabled, the Ultra-Humanite expresses superhero gender norms because the character is Superman’s opponent. Like a female superhero, however, a LGBTQsuperhero disturbs cultural dichotomies that dictate male, heterosexual, cisgender heroes. The 1941 Wonder Woman was preceded by at least eight other female superheroes, and the post-war period produced a surge of short-lived ones, with a second surge in the early 70s, followed a gradual but more lasting increase in the 80s to the present. But sexual orientation and sex identity were considered so socially taboo that the first gay superheroes were not named as such until the 80s and the first transgender superheroes until the 90s. However, where female superheroes are almost always visually overt even when not hypersexualized, gay characters do not necessarily carry visual markers. As a result, readers could interpret characters as gay.

Wertham again provides an early and striking example: “Only someone ignorant of the fundamentals of psychiatry and of the psychopathology of sex can fail to realize a subtle atmosphere of homoerotism which pervades the adventures of the mature ‘Batman’ and his young friend “Robin’” (1954: 189-90). The ambiguity is due in part to Bill Finger modeling Batman on earlier pulp heroes such as the Shadow and the Spider, characters who instead of male sidekicks adventured with female fiancées. Alan Moore, through the autobiography of a retired superhero in Watchmen, identifies “the repressed sex-urge” of these pulps: “I’d never been entirely sure what Lamont Cranston was up to with Margo Lane,” acknowledging that the relationships were not entirely “innocent and wholesome” (Moore & Gibson 1987: “Under the Hood,” 6). Narratively, Robin fulfills the same plot roles of confidante and secondary adventurer. “Like the girls in other stories,” observes Wertham, “Robin is sometimes held captive by the villains and Batman has to give in or ‘Robin gets killed’” (1954: 190-1).

Bob Kane created Robin in 1940 to provide Bill Finger more opportunities for dialogue, repeating the young pal character type of the anthropomorphic Tinymite Kane created for the comic strip “Peter Pupp” while working for the Iger studio in the 30s. The formula spread through superhero comics, with Toro joining the Human Torch and Pinky Whiz Kid joining Mr. Scarlet later in 1940, followed in 1941 by Captain America’s Bucky, Sandman’s Sandy, Black Terror’s Tim, and Superman’s Jimmy Olsen.

The Association of Comics Magazine Publishers apparently did not interpret these relationships as homosexual, and so their 1948 Code did not bar homosexuality, only “Sexy, wanton comics” (ACMP Publishers Code). Though Wertham’s critique decimated male sidekicks, the 1954 U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Juvenile Delinquency did not address the topic. The word “homosexual” appears only once in transcripts, with the publication Homosexual Life listed as an example of “everything of the worst type” that’s been mailed to “youngsters at preparatory schools” (U.S. Congress 1954). New York State assemblyman James Fitzpatrick also condemned transgender characters in his testimony, describing a comic in which a female character “turns out to be a man ─ complete and utter perversion.” When the Comics Magazine Association of America formed two months later, its Comics Code Authority adopted and expanded the ACMP code, with the new “Marriage and Sex” subsection specifying that “sexual abnormalities are unacceptable” and “Sex perversion or any inference to same is strictly forbidden”; as far as the “treatment of love-romance stories,” they must “emphasize the value of the home and the sanctity of marriage” (Code 1954).

[image error]

April 3, 2017

My Morning Memes, part 6

This year’s last nor’easter hit during the very end of winter, but the political blizzard pounded for another two weeks — right up until Speaker Ryan withdrew his healthcare bill because the GOP didn’t have the votes. That took a lot of angry snowflakes. March 20 deserves special notice too, since history books will cite the FBI’s official announcement of its investigation into the Trump campaign’s collusion with Russia to influence the election. It’s of course a pleasure watching the President’s job approval numbers sink into the 30s, and the opportunities for lampooning his hypocrisies are shockingly endless. And 1984 remains the most prescient insight into his Presidency.

[image error]

[image error]

March 27, 2017

How to Interview Someone at Marvel Comics

Short answer: you don’t.

Or at least I didn’t. Not in the sense of talking back and forth with another human being face to face. Or even talking back and forth Skype face to Skype face. Or voice to voice via Skype’s widowed aunt, Phone. I did type back and forth email to email with Senior Communications Manager Joseph Taraborrelli. Though not because I wanted to. No offense to Joe, but I was dialing Editorial, not PR.

There are many wonderful things about pre-tenure leave, and a research trip to NYC is near the top of the list. My northern itinerary included the Society of Illustrators, the comics holdings at the New York Public Library, an evening New School lecture on text-images, plus guest lectures of my own at Marymount University. But it was the visit to Marvel that most curled my former fanboy toes.

Sadly, Marvel doesn’t give tours of its corporate headquarters (135 W. 50th Street). But I didn’t really want a tour. I wanted to talk to people. I particularly wanted to talk to editors. Not Axel Alonso, editor in chief, but regular in-the-trenches editors. And not just editors, but lowly even-deeper-in-the-trench-mud assistant editors. The creation of a comic is a complex business, involving writers, pencillers, inkers, colorists, letters, and, of course, editors. The first five categories I have a pretty good handle on (even though “writing” at Marvel used to mean filling in Jack Kirby’s talk balloons with witty banter and “pencilling” meant figuring out the entire story moment for moment and writing “suggested” dialogue and narration in the margins for the “writer” to use later), but the how-what-where-whens of editing is pretty much a mystery. One I want to solve.

So I wrote an email to Sana Amanat. She edits, among other things, Captain Marvel and Ms. Marvel, and she also can be heard on the podcast Women of Marvel. So I wrote to her via WomenOf@Marvel.com, asking if I could interview her while I was in town. I also wrote to Kathleen Wisneski, who had been featured with several other assistant editors on the podcast and confessed a near-miss career path in comics studies–so she might even understand why an English professor in Virginia is writing a book called “Superhero Comics.” I found her gmail and also tried her on Facebook–having not yet had the Sherlockian realization that Marvel employee emails (like the vast majority of company employee emails across the known universe) consist of first initial lastname@company.com (a theory confirmed by Joe’s JTaraborrelli@marvel.com.)

I think KWisneski hit delete and Samanat forwarded me to JTaraborrelli, as per apparent Marvel policy. The Senior Communications Manager said he would be happy to help me out by forwarding some specific questions to someone other than Sana, who wasn’t available, especially right now, and could we maybe revisit this in November? Since that would be two months after my two-day stop in NYC, I kept trying, sending new emails when previous ones hit their one-week expiration date in Joe’s Inbox and/or Deleted file.

Unfortunately, Joe could not grant an in-office interview. No problem, I’ll meet anywhere. Like the lobby. Or the sidewalk out front. Seriously, anywhere. Like many skilled managers the world over, Joe is artful at evasion, answering by not answering and instead offering again to forward some questions. So I sent him some questions. And, after the next email expiration date, asked again for a face-to-face, eventually getting an “email is easier for us” and another offer (the third) to forward some questions to an unnamed someone else. So I sent him my questions yet again.

Oh, and you can’t phone anyone directly at Marvel. All calls go through the main switchboard (212 576-4000) where the operators know how not to give out individual extension numbers. Or to connect you to anyone in any department other than PR–where Mr. Taraborrelli’s line goes to phone mail when my Virginia area code appears on its screen. Which is all perfectly reasonable. They’re busy people. Plus imagine the onslaught of enraged fans and non-fans demanding to see the people responsible for turning Captain American into a HYDRA-hailing Nazi last summer. Of course they don’t offer “tours.”

But still, Joe, is fifteen minutes with Ms. Wisneski talking nuts-and-bolts editing really such an impossible request? My questions could well be winding their way through the internal Marvel ether to the screens of any number of editors or assistant editors as I type, but should they have vanished through some off-continuity wormhole, here they are yet again:

1. How are story ideas developed? Do ideas typically originate with writers, artists, editors, or other individuals–or does it vary with each story?

2. Do writers typically write panel-by-panel scripts, or are page-by-page or even scene-focused scripts common too? If panel-by-panel, how much detail is preferred? Does this vary according to the writer-artist relationship, or do editors maintain a standard approach? Is there a standard Marvel script format?

3. At what stages do editors enter the creative process. For instance, does an editor always see a script before the artist receives it? What kinds of scripts revisions might an editor ask for before passing the script to an artist? How many revisions might a typical script undergo at this pre-art stage?

4. Once the artwork has begun, when do editors typically view the products–per page? per full story? Given current technology, is the creative process still defined by a strict pencil layout followed by inking? At what stages of completion does an editor enter the art process? What kinds of revisions might artwork undergo? In past decades Marvel maintained a house style. To what degree is that still true? How is artwork evaluated in terms of whether a pre-existing character is drawn to match expectations?

5. Does the artwork ever cause alterations in the originating script? If so, are those changes made by the writer or the editor? Do they entail rewriting the script itself, or are they only incorporated into the comics pages?

6. How are writers and artists assigned to a project? How often are the pairings initiated by the creators and how often are they assigned to each other by editors? How are pencillers, inkers, and colorists assigned?

7. Given the serial nature of comics, how far in advance of publication are issues scripted, drawn, and completed? In past decades, there seems to have been roughly a four-month production period. Is that still accurate? How might reader response, including sales, influence the process? Are scripts and art ever changed mid-course as the result of reader reactions to current issues?

And these are the ones that apply specifically to Sana Amanat:

As editor of Ms. Marvel, you oversaw the art of Adrian Alphona, whose style for the series was a major departure from his earlier work on Runaways. I would like to ask about that and also the equally distinctive and highly divergent art of Dexter Soy, Emma Rios, and Filipe Andrade in Captain Marvel. In the past Marvel has emphasized visual continuity, and so I would like to ask about that change in editorial control. Does she and Marvel in general now prefer artists with individualized and often less naturalistic styles?

And here’s my NYC hotel, where I was while in town when I wasn’t somewhere else in town, including when I was not interviewing absolutely anyone at or in the general vicinity of Marvel headquarters:

March 20, 2017

Gender-Flipping the Odyssey

Guest blogger, Madeleine Gavaler:

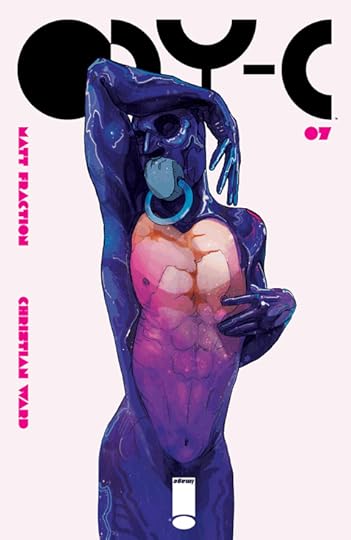

Greek mythology is, at its core, about rape. This makes a gender-flipped telling of the Odyssey an interesting endeavor. In ODY-C, two white boys, Matt Fraction (writer) and Christian Ward (artist), depict Odyssia and her gals’ long, intergalactic journey home after the war in Troiia (yes, even the city of Troy gets a fun gender change).

At its surface the book is a retelling of the Odyssey, but Fraction’s own convoluted gender mythology overshadows any deep engagement with the source text. ODY-C turns out to be a little more complicated than a binary-implying gender swap—Homer’s male characters become women, but the meager supply of female characters doesn’t all become men. Instead, Fraction has a very busty and plus-sized female Zeus kill all the boys.

In Homer’s vision, the Trojan War was fought because men think they can own women. All of this violence was inspired by rape culture, so giving the characters vaginas doesn’t suddenly turn the Odyssey into a fun, feminist adventure—the story is still about rape, only its object is (very subtly) not Helen but He.

Instead of an innocent gender swap, Fraction chooses to have a very powerful woman violently destroy all men out of her own greed and egocentrism:

“I am Zeus, who murdered her own father in violent spite, in Olympus itself, on his bloody throne from which he created all things… To make sure no child could ever be born to a woman again that might come for my head the way I came for my father’s… I destroyed all men.”

Womankind can still reproduce, however: Prometheus-turned-Promethene, rather than giving fire to man, gives women a new gender to fuck: Sebex, “who could implant the released ovum from a woman and fertilize it within its womb.”

Instead of there simply not being men, or women being able to reproduce by themselves, Fraction finds it necessary to introduce a new slave-sex gender and make men the victims of a bloodthirsty female tyrant. Women rule the galaxy, but Fraction implies that this is not of their own merit but rather Zeus’s villainy. Girl Power is overshadowed by the injustice of the men Zeus destroyed.

There are still a few men left however, including “He” (Helen). He walks on all fours, with his wife yanking on the leash around his neck. Riffing on Faustus, Fraction writes “Thousands of swiftships once launched in his name.”

Odyssia asks He, “Was that face of yours really so beautiful?”

“Once, maybe, yes,” Ene (Menelaus) admits. “Yet across it I carved my own name so that no one could want him again.”

In both Ene’s treatment of He and Zeus’s destruction of man, Fraction highlights the politics of gender and violence that are central to Homer and Greek mythology. After all, Menelaus abusing and disfiguring Helen to show his rapey power of her would not be entirely out of character or out of place for Homer. Nor would Zeus’s actions—Greek gods, especially Zeus, are known for being petty and violent and deeply flawed. Homer is violent and weird and even upsetting, and Fraction ends up being more honest to these themes of the poet than his awkward attempt at matching Homeric syntax.

Fraction (partially and problematically) hits on what has always fascinated me about Ancient Greece and its deities: the mythology is so deeply misogynistic, and yet occasionally incredibly feminist and liberating (not to mention incredibly gay). Athena and Artemis, some (arguably sapphic) bad ass bitches, have always been role models of mine, and even Homer’s more male-focused masterpieces feature empowered women: Helen might fall short (although I’ve always liked her), but Athena, Hera, Penelope, and Circe are each certainly more deserving of an epic than Aeneas.

ODY-C isn’t a feel-good story about female empowerment, but it is a fascinating exploration of gender and power in Homer. By villainizing characters such as Zeus and Menelaus far more than Homer or Virgil ever did, Fraction acknowledges the unspoken horrors of our beloved classic literature. Still, depicting genocide of the boys is a convoluted way to criticize rape culture.

Fraction makes a valiant feminist attempt to reveal the ugly gender roles in the Odyssey, but by both feminizing the characters and making them more villainous, his result is anti-feminist: he implies that if women were in charge, they would be more possessive and violent to men than men were to women in the Odyssey.

When asked about the book’s inspiration, Fraction said, “I wanted to write a classic mythological hero for my daughter.” Seeing Odysseus as one of the original heroes, he made her Odyssia and went from there. He hoped that his “inversion of the patriarchal structure” would “show how women have been treated for 26 centuries.” However, creating an evil matriarchy didn’t exactly serve that end.

He had sweet intentions, but Fraction’s daughter is better off reading Bitch Planet.

Chris Gavaler's Blog

- Chris Gavaler's profile

- 3 followers