Chris Gavaler's Blog, page 47

July 31, 2017

Bicycling into the Trump Era

You & a Bike & a Road is Eleanor Davis’ personal exploration of the roadside American southwest, U.S. immigration politics, and the autobiographical comics form. Unlike graphic memoirs, which allow authors to shape their narratives with the guiding awareness of their conclusions, Davis commits to the more challenging limitations of unedited diary entries that progress as she herself progresses on a 2,300-mile bike journey. She, like her readers, doesn’t know whether she will be able to complete her planned Tucson-Athens trip or, more importantly, overcome her suicidal depression. When people ask, she says she doesn’t want to put the trip off until after she’s had a baby or, less convincingly, that she doesn’t want to ship home the bike her father made for her. “I don’t say,” she paradoxically says: “I was having trouble with not being alive.”

After establishing high personal stakes, Davis steers onto political terrain. Her 2016 journal begins March 16th and ends May 13th. During that two-month span, Donald Trump raced from front runner to sole remaining candidate in the Republican primaries. Davis never mentions Trump, but his presence haunts her narrative—if only retrospectively since the journaling Davis does not have her readers’ hindsight to know how his immigration policies would resonate a year later.

On Day 3, her thought balloon wonders “Border patrol?” as a helicopter—drawn not from her perspective but a higher, seemingly omniscient one—dwarfs her tiny cartoon self. Her narrating text floats in the open spaces surrounding the images: “They circled around tight and then flew down very low. I guess low enough to see the color of my skin.” Day 4, a distraughtly drawn B&B owner warns her against sleeping in the desert, but Davis decides “not to listen to anyone who uses the word ‘illegals.’” On Day 6, she estimates one of every six cars is border patrol. The WUB WUB WUB of patrol copters follows her to the Rio Grande, where her carton self looks back to shout, “FUCK YOU, NEW MEXICO.” But Texas proves worse. In the book’s longest multi-page sequence, she watches a patrol team try to lasso a man from a river: “I’d thought he was a big man, but when I moved around to see his face he’s thin and young.” A page later and a patrol blimp hovers at the margin of the open sky.

Though Davis stays with a generous couple who “hate Republicans!”, she doesn’t vilify. On Day 30, she asks a border patrolman for water and he gladly gives it–without asking for her I.D.: “Why would he?” Patrols vanish once she leaves Texas, but Day 50 she rides through a Louisiana military reserve with Arabic signage and an empty “recreation of an Afghan town” that evokes a decade of middle east war. Five days later, Davis ends her trip in Mississippi as she waits in a “Historic Plantation House” with a Confederate flag hanging from a porch column. “Nostalgia for an evil time,” narrates Davis, but then she gives the widow who runs the B&B a seven-page sequence, the book’s second longest, ending with Davis in tears of sympathy.

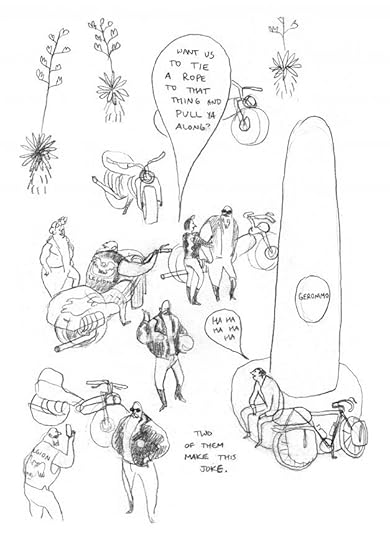

Much of the journal is portraits of such strangers, usually people Davis chats with as she stops to eat or ice her knees: a moustached man in Starbucks asks about her preference for frozen green beans; two Hell’s Angels-like motorcyclists jokingly offer to pull her by a rope; a weightlifter-sized acupuncturist in granny glasses tells her to take better care of herself; a widowed bartender introduces her to his new wife; a fellow bicyclist teams up with her against the Austin traffic. “We’re both loners,” explains Davis, “so we like each other,” but she seems to have found the same kind of connection with everyone she draws: “Meet some strangers. Get to know them and they get to know you. Now they are your people.”

Older friends appear, and her parents, who drive twice to meet her, and her husband who Davis draws always seated at his desk with their cat as they speak by phone—but the core character is of course Davis. Her journal is not a sequence of drawn snapshots taken from her sketchbook’s roaming point of view. Instead, Davis consistently draws herself into scenes, imagining her appearance more than documenting it. Her physical self, even when not drawn, is always narratively present. That body is also specifically female—evoking fear on her behalf from strangers, as well as Davis’s own fantasies of stabbing would-be rapists in the face. She draws only slightly less blood when washing her hands off in an abandoned church yard after forgetting to put in a tampon. With the exception of a half-nude washcloth bath in a presumably locked public bathroom, Davis draws herself androgynously. She, like everyone else, is a few, gestural lines, rarely more than an outline with a minimal number of internal lines to define basic features. Those features are intentionally cartoonish, with her head impossibly tiny atop a wide and often breast-less torso. Emanata radiate from her crosshatched knees—her most important body parts and the narrative’s most repeated heroes and obstacles. Shortly before Davis calls her husband to pick her up a month and a state early, her legs are ropes of skinless muscles, the journal’s most detailed drawing.

Her decision is anti-climatic, not simply because it ends the intended narratively prematurely, but because Davis depicts the event briefly and with little reflection: “Oh! It would have felt so good to bike all the way there! But if feels good, too, to let myself stop.” She acknowledges in her July afterword: “50-mile days for multiple weeks was too much for me…. Learn from my mistakes!”, but the larger stakes she established in the opening pages receives no gestures of closure.

But formally the graphic journal remains a success. By writing and drawing each numbered entry while in route, Davis interrogates the nonfiction norms of graphic storytelling. “On the map,” she writes on Day 1, “Marshstation looks like this,” and draws a single winding line of a road. On the facing page, she writes: “In real life, it looks like this,” and draws a vibrant landscape—but rendered in the same line quality and with symbolically simplistic details that make the image less “real” than the accurately duplicated map. Davis twice draws herself drawing journal pages, a meta effect heightened by the placement of the internal content—the carefully rendered border patrol scene—on the previous pages: “I spend all morning drawing a comic about a young man I saw getting arrested in Fort Hancock.” Day 55 she laments: “Well, if my knees weren’t slowing me down, I certainly wouldn’t be drawing all of these comics,” emphasizing that all of the images of Davis in motion were drawn while Davis was stationary. The paradox is common to comics, and Davis acknowledges it early in the journals’ only framed images—the three-panel row depicts a bird in motion—except Davis’ text contradicts the drawn effect: “There’s a bad headwind … Across the road from me is a hawk going my way. He’s flapping his wings but he’s just hanging there, not moving forward at all.”

Davis, however, does move forward—through space, politics, her life, and the comics form.

[The original version of this and my other recent comics reviews appear in the comics section of PopMatters.]

July 24, 2017

The Prepubescent Brains of Supermen

My colleague Ed Adams observes an improbable shift in Victorian literature in which “war epic becomes largely a province of childhood and a pleasure reserved for children—or for adults relaxing into a juvenile mood” (49). Superhero comics share the same audience—or they did for their first half-century. Sanitized violence dominated the genre from its inception in 1938 through the mid-80s when the Comics Code increasingly lost its control over the industry. Once Kent Williams painted Wolverine’s claws punching through the eyeballs of a random thug in the non-Code-approved Havok & Wolverine: Meltdown, the genre could no longer be defined entirely by its pubescent audience.

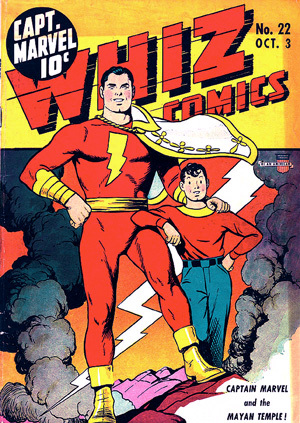

But superhero comics did achieve their defining success in the juvenile market, and the character type may be especially adapted to adolescent readers. Captain Marvel creators Bill Parker and C. C. Beck reflected their intended audience through their leading character’s alter ego, twelve-year-old Billy Batson in Whiz Comics #2.

Since puberty typically occurs for girls between the ages of ten and fourteen, and for boys between twelve and sixteen, Parker selected an especially representative age. Every time Billy transforms into the hypermasculine superhero, he enacts a pre-pubescent wish-fulfilment. The puberty metaphor, never far below the surface text, extends across the genre’s decades of publications. Stan Lee and Steve Ditko developed it further in 1962 by featuring a teenaged superhero as a title character. After being bitten by a radioactive spider, Peter Parker declares: “What’s happening to me? I feel—different! As though my entire body is charged with some sort of fantastic energy!” Spider-Man’s readers may have experienced their bodies’ transformations too.

Developmental psychology also provides additional parallels. David Elkind introduced the concept of adolescent egocentrism, a developmental stage that includes the “imaginary audience” and the “personal fable,” a belief in one’s invulnerability, omnipotence, and uniqueness—traits that describe most superheroes. One textbook makes the analogy explicit:

“Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four, stand aside! Because of the personal fable, many adolescents become action heroes, at least in their own minds. If the imaginary audience puts adolescents on stage, the personal fable justifies being there. […] It also includes the common adolescent belief that one is all but invulnerable, like Superman or Wonder Woman.”

Fredric Wertham described a similar “Superman complex,” reporting to the 1954 Senate subcommittee juvenile delinquency that comics “arouse in children phantasies of sadistic joy in seeing other people punished over and over again while you yourself remain immune.” Wertham argued that the complex was harmful to children’s ethical development, but a 2006 study found that the fable’s omnipotence correlated with self-worth and effective coping; uniqueness with depression and suicide; and invulnerability with both negative and positive adaptational outcomes.

Whatever its developmental effects, the personal fable could also increase reader identification with the superhero character type, providing a further explanation for the popularity of the genre with its original age group.

Lawrence Kohlberg’s theory of moral development provides another explanation. Kohlberg outlined six stages, placing twelve-year-olds at the intersection of three. Most children leave stage four by the age of twelve, expanding interpersonal relationships to the rigid upholding of social laws that characterizes stage four conventionality. Twelve is also the earliest age that stage five reasoning appears—though Kohlberg estimates that less than a quarter of adults achieve it or a stage six level of post-conventionality. Superheroes, however, do. As a character type, the superhero evaluates morality independently of governments and legal systems, relying instead on personal judgement based on universal principles. Superman, observes Reynolds, displays “moral loyalty to the state, though not necessarily the letter of its laws” and is willing “to act clandestinely and even illegally” to achieve it (15–16).

Superheroes are independent moral agents, devoted to a higher good which they alone can define. This is also the general definition of “hero” that coalesced in the first half of the nineteenth century. German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel praises “heroes” such as Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, and Napoleon as

“thinkers with insight into what is needed and timely. They see the very truth of their age and their world, the next genus, so to speak, which is already formed in the womb of time. It is theirs to know this new universal, the necessary next stage of their world, to make it their own aim and put all their energy into it. The world-historical persons, the heroes of their age, must therefore be recognized as its seers – their words and deeds are the best of the age.”

Hegel’s 1820s’ lectures on the philosophy of history were published in 1837, six years after his death, and four years before Scottish writer Thomas Carlyle’s On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and The Heroic in History, in which Carlyle proposed his “Great Men” theory:

“Find in any country the Ablest Man that exists there; raise him to the supreme place, and loyally reverence him: you have a perfect government for that country; no ballot-box, parliamentary eloquence, voting, constitution-building, or other machinery whatsoever can improve it a whit. It is in the perfect state; an ideal country.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson echoed it in his Representative Men:

“Mankind have in all ages attached themselves to a few persons who either by the quality of that idea they embodied or by the largeness of their reception were entitled to the position of leaders and law-givers. […] The great, or such as hold of nature and transcend fashions by their fidelity to universal ideas, are saviors from these federal errors, and defend us from our contemporaries.”

Hegel, Carlyle, and Emerson also share assumptions that Ed Adams links to the popularity of the epic: “that wars were the most important of historical events; and that individuals possessed the agency to determine their outcomes” (34). Beginning in the early nineteenth century, that tradition shifted to juvenile fiction, as authors such as Carlyle and Tennyson rescued “modern faith in heroes by self-consciously appealing to primitive, childish beliefs” (52). The great man of epic history began its transformation into children’s adventure hero in 1844, when French novelist Alexander Dumas described the titular hero of The Count of Monte Cristo as one of a new breed who “by the force of their adventurous genius” is “above the laws of society.” Siegel and Shuster drew on the same hero type a century later, transforming so-called great men into the comics genre of superheroes.

July 19, 2017

Rotu Modan’s Exit Wounds

Rotu Modan’s 2008 graphic novel Exit Wounds is an unusual and unusually effective variation on traditional detective fiction. Numi, a wealthy young woman completing her mandatory service in the Israeli armed forces, enlists Koby, a young man driving a taxi for his family’s business in Tel-Aviv, on her search to discover the identity of a corpse unclaimed after a terrorist bombing. She believes it was her lover, Koby’s father. A DNA test will prove it, but Koby, who hasn’t seen his father in years, thinks he abandoned Numi as he abandoned Koby’s family. Before agreeing to exhume the body, Koby needs evidence, leading the unlikely partners into a personal investigation of the bombing and its surviving victims and witnesses.

While Numi drives the plot, Koby is its reluctant narrator. Modan uses captions boxes for Koby’s internal speech, blurring the lines between thought, recollection, and omniscience. The novel opens with the caption: “Tel-Aviv, January 2002, 9:00 AM”, a standard convention for establishing scenes, which she repeats at least six times, including for minor time leaps: “Next morning” and “Two hours later”. The brief, impersonal statements of fact imply a remote narrator, but Koby’s language dominates other captions, as established on the fifth page when he reflects on the differences between his aunt and his “pushover” mother: “How different can two sisters be?” The present tense is significant as it establishes narration linked to the moment of the images, as when Koby enters his father’s abandoned apartment: “It’s been years since I was last here.” When captions appear during scenes of dialogue, they serve even more fully as thoughts balloons.

Numi’s speech bubble: “I haven’t heard from him since.”

Caption box: “That sounds like Dad all right.”

Koby’s speech bubble: “How do you know the scarf is his?”

At other times, Koby’s narration is free to shift forward in time, implying retroactive narration, with the words and images occurring at different moments. After their investigation reveals an unwanted truth and Koby and Numi depart estranged, Koby opens the next chapter: “I worked like crazy for three months,” with the images depicting the past relative to his speech.

The variations seem practical rather than experimental—especially in the case of substitute thought balloons, since thought balloons have largely fallen out of fashion in the comics lexicon. Modan’s overall visual approach is accordingly understated. Only speech bubbles break frames, and foregrounded subjects are brightly colored, as backgrounds fade into undifferentiated grays.

Layouts follow a three-row norm, punctuated with occasional two- and four-row pages and paired sub-columns breaking Z-path reading without suggesting thematic significance. Koby and Numi’s first meeting is an exception. Their full-length figures appear in the novel’s first paired sub-column, creating a brief N-path, before returning to standard left-to-right reading in the bottom row. Their shared panel is striking both visually and narratively, as it reveals that Numi is slightly taller than Koby, a repeated fact central to the romance plot and the novel’s conclusion.

Though Modan draws in a minimally detailed but naturalistic style, she also employs standard non-naturalistic effects: emenata lines of surprise radiate from characters’ heads; diagrammatic arrows indicate movement direction. Though her artistic choices emphasize story clarity over form, her most significant visual effect is what she does not draw. While the comics form itself relies on juxtapositional closure to imply undrawn narrative content, Modan heightens this quality by never depicting the novel’s most central and plot-driving character: Gabriel, Koby’s estranged father and Numi’s missing lover. Whether he’s just below the surface of the burial plot that Numi cleans, or just minutes away from returning to his apartment while Koby sits with his new wife, Gabriel’s absence is omnipresent. He’s part of the white space defined by the unbroken gutters.

Modan also never depicts Palestinians. Their presence is felt in the aftermath of multiple terrorist attacks, another core but unremarked omnipresence of the novel. Gabriel is a villainous character, one who simultaneously woos and abandons multiple women, including Numi, and yet Modan also offers multiple redeeming qualities: his visits to his first wife’s grave, the checks he mails to Koby and his sister after selling his apartment, his new religious devotion, the love of his new wife whom, unlike Numi and his other lovers, he has actually married. And though ultimately he was not killed in the bombing, Numi’s belief emphasizes his role as victim for most of the novel. The split characterizations prevent Gabriel from resolving into any simple category—victim, hero, villain—and so suggests a similar attitude toward Palestinians.

Gabriel and Palestine further coalesce through the novel’s two most central yet repressed events: the bombing of a station cafeteria in Hadera, and Numi and Gabriel’s sexual relationship. Both haunt the story, with literal glimpses and verbal reports slowly bringing the bombing into retroactive focus. The sexual relationship, however, receives no direct acknowledgement until the novel’s most pivotal moment. After Numi rages at herself for not realizing sooner that Gabriel had never intended to move to Canada with her, she and Koby kiss.

The following six-page sex scene features Modan’s most formally significant image. While every other panel juxtaposition involves some degree of temporal and spatial closure, Modan depicts Numi and Koby’s intercourse in the novel’s only use of Gestalt closure: though divided by a white gutter, their two bodies are continuous across adjacent panels, implying a subdivided but single image. The effect is especially striking in a novel so much about the emotional isolation of surviving victims. For a single moment, Numi and Koby not only break the white borders that define their worlds, but they do so together.

The moment is brief though, because Numi then acknowledges the novel’s most taboo event. As Koby kisses her nipple, she says: “Like father like son.” Her speech bubble appears in a panel that nearly achieves the Gestalt effect of the preceding page, but this panel pairing is slightly misaligned, with Koby appearing continuous but Numi partly doubled. The doubling is also psychological: she’s recalling sex with Gabriel as she’s having sex with Koby. For most of the novel, Numi believes Gabriel’s body has been burnt beyond recognition. Now, after revealing that Gabriel is alive and continuing a sexual relationship with a new woman, Modan evokes Gabriel’s body through Koby’s. The two taboo images—a burnt corpse and a naked 70-year-old man having sex with a 20-something woman—merge, too. When Koby angrily stops, rolls off of her, and dresses, Numi explains: “He’s there … I just can’t erase him.” It’s the defining sentence of the novel.

Modan doesn’t end the story so bleakly though, allowing Koby his own redemption and at least the possibility of him and Numi continuing a relationship in their mutually haunted world. The final image is an almost literal cliffhanger. Having trapped himself in a tree while attempting to reach Numi on her family’s private estate, Koby has no way to get down but to leap into Numi’s outstretched arms. Modan appropriately ends the novel with Numi’s view of Koby’s falling body.

[The original version of this and my other recent comics reviews appear in the comics section of PopMatters.]

July 10, 2017

Modernist Comics

The present-day genre of comics might begin with Rodolphe Topffer in 1837; Punch magazine’s 1843 satiric cartoons; Richard F. Outcault’s 1895 The Yellow Kid; Famous Funnies, the U.S. magazine that standardized the comic book format in 1934; or Action Comics, the 1938 series that turned the fledgling industry into mass culture in a single bound. When defined by formal qualities, however, comics date to at least the Medieval period, with a long tradition of panels and speech scrolls in illuminated manuscripts establishing conventions that would become standard in newspaper strips and graphic novels in the 20th century.

Because the rise of comics coincides with the ebbing of Modernism, and because Modernism often is defined in opposition to popular culture, the notion of “Modernist Comics” might appear oxymoronic. As Jackson Ayers writes in the introduction to a three-essay “Comics and Modernism” section in the Winter 2016 Journal of Modern Literature, comics are “Modernism’s wretched Other.” Yet the wordless woodcut novels of Frans Masereel, Lynd Ward, Giacomo Patri, and Laurence Hyde, as well as Max Ernst’s surrealist collage novel A Week of Kindness, can be analyzed fruitfully via comics theory. Further, the image-incorporating poetry of Langston Hughes, the concrete experiments of Guillaume Apollinaire, and even the page-space arrangements of William Carlos Williams all employ visual strategies common to later comics and comics poetry. Finally, the comics of George Herriman, Lyonel Feininger, Windsor McCay, and other early 20th century creators might be reevaluated as Modernist texts.

That’s the call-for-papers I posted on the Modernist Studies Association’s conference webpage last year. Happily three other scholars took interest and submitted proposals, which I then compiled into a a panel proposal and sent to the MSA organizers, who, more happily, accepted it:

This panel will explore such lines of inquiry between Modernism and comics through the following papers:

“Human Desire: Marc Chagall’s Caricatural Illustrations for Dead Souls”

Jessie Kerspe (Shu Hsuan Kuo), PhD, Leiden University Centre for the Arts in Society

Marc Chagall’s 96 illustrations for the Russian author Nikolai Gogol’s epic novel Dead Souls (Les Âmes Mortes, 1923-27) can be seen as an example of modernist comics in a broad sense. Despite the format of book illustrations, the large amount of 96 pictures in fact contributes to a coherent reading of the story like today’s sequential arts. Chagall’s caricature styles such as pictorial hypallage, abstraction and uneven proportions, respond appropriately to Gogol’s writing techniques of hyperbole and metaphor. Through the comical presentation, Chagall’s illustrations emphasize on the bodily desires implied in the novel and therefore visualise the world of feast and eroticism, as in Bakhtin’s carnival aesthetics. As an early modernist artist, Chagall’s choice of illustrations reflects not only his own identity of Russian roots, but also the correspondence to his contemporary publications of livres d’artiste (artists’ books), as well as the activities of Jewish avant-garde artists.

“A Battle of Wills: Wood, Materiality, and Affective Production in Ward’s Woodcut Novels”

Olivia Badoi, PhD Candidate, Fordham University

The newly rediscovered genre of the woodcut novel can help us re-examine existing theories on modernism and the art object. Departing from Adorno’s notion of the artistic material as “historical through and through”, wood can indeed be regarded as the “artistic material of modernity”. I will focus on the work of the American artist Lynd Ward. From the eve of the great depression to the onset of the second world war, Ward crafted his wordless graphic narratives using not only the oldest material, wood, but also the oldest printmaking technique. While this choice seems paradoxical and anachronistic in the age of unprecedented technological development, it is reflective of modernist anxieties such as a sense of overwhelming acceleration, and a generalized feeling of loss of authenticity and of emotion. Reading a wordless woodcut novel requires a certain kind of reading praxis, one which implies a certain level of defamiliarization: literature is transformed from prose to visual art, while simultaneously, visual art is transformed into literature. In the process, the experience of time becomes less linear, meaning is rendered more malleable, and thus more difficult to manipulate and control.

At a time when the function of language as a tool of mass manipulation became increasingly and painfully evident, Ward’s refusal to engage with words inscribes the woodcut novel within a larger modernist project of denaturalizing and de-stabilizing language as a known, finite and fixed category in a radical way – by doing away with words entirely, and instead offering as alternative a purely visual means of communication that is centered on emotion.

“Comics and Modernism’s Little Magazines”

Suzanne Churchill, Professor, Davidson College

Rather than reading comics as “modernism’s wretched other,” we can see the little magazine, which was so generative of modernism, as a comics form that not only deploys actual comics drawings but demands us to read and enact closure in some of the same ways that later comics do. I will explore the use of comics in Rogue magazine, including those by Clara Tice and Djuna Barnes, and in the Little Review, including a series portraying the editors’ activities making the magazine, and on the cover of The Blind Man. Together these examples argue for an understanding of the modernist little magazine as a verbal-visual form that is informed by comics and demands to be read using similar multimodal strategies.

“The Proto-Barksian Dialect of Frans Masereel”

Chris Gavaler, Assistant Professor, Washington and Lee University

Comics scholar and cognitive psychologist Neil Cohn identifies two major artistic “dialects” in contemporary comics, “Kirbyan,” after superhero comics artist Jack Kirby, and “Barksian,” after Donald Duck artist Carl Barks. Comics historian Joseph Witek similarly divides comics genres between the naturalistic mode and the cartoon mode, divisions that parallel Cohn’s. Beetle Baily artist Mort Walker was the first to define the norms of the Barksian dialect / Cartoon Mode in his 1980 The Lexicon of Comicana. It is striking then how thoroughly German artist Frans Masereel demonstrates and so prefigures these later norms in his woodcut novels The Sun (1919), The Idea (1920), Story Without Words (1920), and The City (1925). In addition to a style that employs the simplification that Scott McCloud identifies as central to cartooning, Masereel establishes Witek’s cartoon “ethos,” one in which stories “assume a fundamentally unstable and infinitely mutable physical reality, where characters and even objects can move and be transformed according to an associative or emotive logic rather than the laws of physics.” Masereel’s woodcuts then are not only foundational graphic novels, but also evidence of Modernism’s defining and enduring influence on the comics form.

The panel has since evolved. Suzanne had the happy dilemma of being booked on too many panels (MSA is strict about that), and Jessie had the unhappy dilemma of not getting travel support from her institution. But, happily again, Lesley Wheeler has just joined the panel to present “Anne Spencer and the Comics.” The conference is the second weekend of August and, even more happily, in Amsterdam. Our kids are coming too.

July 4, 2017

Thomas Jefferson, Stan Lee and God

There’s an atheist in the Oval Office!

While not busy expanding his federalist agenda, he sits at his White House desk with a razor, literally slicing the New Testament down to his own, non-“superstitious” edition. The miracles, the resurrection, any mention of Jesus Christ’s divinity, they’re all cuttings in his tax-financed waste basket.

I would demand Congress begin immediate impeachment proceedings, but God has already struck the sinner down. His name was Thomas Jefferson, and he died in 1826. To be accurate, deists aren’t atheists, and the Oval Office wasn’t built yet, but we still can’t allow this sort of wanton division of church and state to fester in our history books. I demand an immediate reboot erasing the author of the Declaration of Independence from all canonical texts.

Jefferson was called a “howling atheist” and infidel even before he edited The Jefferson Bible (“Should the infidel Jefferson be elected to the Presidency, the seal of death is that moment set on our holy religion”), but the founding father was neither the first nor last to edit the gospels into personal coherence. They originally numbered in the dozens, until the Council of Laodicea officially razored them down in 363 AD. The Children’s Bible my parents gave me when I was two says the New Testament begins with four books, “but as they contain one message, they are combined as a single story.” The Golden Press advisory board included a rabbi, who I doubt agreed “the New Testament completes the Old.” According to the 1968 inscription, “from Mommy & Daddy,” it was a Christmas present. Jesus is drawn with blonde hair and beard inside, but a surprisingly dark-skinned, turbaned man walks beside a camel on the spine—an image my heretical imagination interpreted as a camel-headed man for years and years.

My imagination was more at home interpreting Marvel Comics. They were still being edited by Jewish heretic Stanley Lieber, AKA Stan Lee. His uncle, Martin Goodman, sold Marvel to another company in 1968 but stayed on as publisher till 1972, when Lee took over, handing his Editor plaque to a string of apostles. Though Lee’s Jewish parents immigrated from Romania, he “always tried to write stuff that would be for everybody. I never wanted to proselytize.” When asked about all the Jewish artists and writers he worked with, he ticks off the names of all the Italians instead. He had nothing to do with the Thing’s conversion to Judaism. He’s proud of Izzy Cohen though, the Jewish soldier he created for Sgt. Fury’s Howling Commandoes, but only because Izzy was part of “the first fully ethnic platoon in comics,” which included a black soldier, an Italian, an Englishmen, and an American Indian—“everything I could think of! A full international platoon of all religions and people.”

Though “not a particularly religious person,” Lee says he “read the Bible” and loved “the phraseology,” all those “Thous and Doths and Begets,” which were “definitely in my mind when I was writing things like Thor.” More than a little phraseology crept into Spider-Man. When Peter Parker’s Uncle Ben tells him “with great power comes great responsibility,” he’s paraphrasing Luke 12:48 (“From everyone who has been given much, much will be demanded”) and Acts 4:33 (“And with great power gave the apostles witness of the resurrection of the Lord Jesus: and great grace was upon them all”). And the whole tragic twist of Lee’s Silver Age superheroes—that superpowers are both a blessing and a curse—comes down to one word from Job 1:5, “barak,” which can be translated either “blessing” or “curse.”

When asked if there’s a God, Lee answered: “I really don’t know. I just don’t know.”

Thomas Jefferson was more diplomatic. He names “Nature’s God” in the first sentence of the Declaration of Independence, men’s “Creator” in the second, and “divine Providence” in the last. Still, the U.S.’s 5th President and Marvel’s 4th Publisher have a lot in common. Like Lee, Jefferson kept religion out of his workplace, coining the “wall of separation between church and state.” As a deist, Jefferson believed God, like a clockmaker, manufactured human beings, wound them up, and watched them go. Stan says the same:

I gave them minds as I recall

It was all so long ago.

I gave them minds that they might use

To choose, to think, to know.

For the hapless weak must need be wise

If they would prove their worth.

And then I gave them paradise

The fertile, verdant Earth.

At first I found the plan was sound

And somewhat entertaining.

But once begun, the deed now done,

My interest started waning.

The seed thus sown

The twig now grown

I left them there

Alone.

Those are stanzas from Lee’s 1970 poem “God Woke” (first published in Jeff McLaughlin’s collection of Lee interviews in 2007). Lee never assigned the 8-page text to any of his artists, so The Lee Bible, unlike The Children’s Bible, isn’t illustrated. It describes our Creator waking up from a cosmic nap with a nagging half-memory of Earth and so returning to see how humanity has been faring without Him. He doesn’t much like “the man sounds everywhere,” but the one that sends him into despair is “The haunting, hollow sound of Prayer.”As Thomas Jefferson or any other good deist would tell you, God doesn’t answer them. Lee’s God laughs at all the “ranting” and then frowns and sighs with boredom. He doesn’t like all the hypocrisy, but its people’s yearning for Him that’s most baffling. Finally, the “carnage, the slaughter” in His name brings Him to tears as “He looked His last at man,” once again leaving us on our own.

Stan Lee might not be the most skilled poet in creation, but he is a bit of deistic God. Like Jefferson’s Grand Architect, Lee set the Marvel pantheon into motion, then stepped back and watched his bullpen spin the wheels of his multiverse. In addition to all those other miraculous godmen who self-sacrificingly save humanity once a month, he and Kirby crafted the perfect human being (via a group of sketchy scientists) in 1967. Known only as “Him,” the God-like super being destroys the evil scientists and abandons Earth. That is until Lee abandoned his Editor post and first apostle Roy Thomas resurrected “Him” as a Counter-Earth Jesus rechristened Adam Warlock. The super savior battles the anti-Christ-like Man-Beast, while beseeching Counter-Earth Creator, High Evolutionary, to spare the flawed world from his disappointed wrath. Adam Warlock became one of my favorite characters, though my pre-adolescent self never could interpret those subtle biblical allusions.

The Roy Thomas Bible is probably no more heretical than The Jefferson Bible, though Jefferson would still object to the superstitious miracle-working. Gil Kane drew Adam Warlock as a homage the Golden Age Captain Marvel, but he later acquired force fields, teleportation, and lightspeed too. Marvel recently collected all of the multi-authored adventures into a single bible (the word just means “books”). It would take a Thomas Jefferson to edit Essential Warlock into coherence, but I’m still fond of all the nostalgically jumbled plots and missteps. I should give it to my son for Christmas.

June 26, 2017

Why Are Superheroes So Popular?

Joseph Campbell fans might think superheroes are popular because superheroes follow Campbell’s monomyth and so are parts of our collective subconscious.

I have my doubts.

A half-century after Campbell published The Hero with a Thousand Faces, the study of “cross-cultural regularities” in folktales and mythologies shifted to cognitive psychology and the search for “a set of conceptual mechanisms that is pan-cultural” and “essentially inevitable given innately specified cognitive biases” (Barrett and Nyhof). So members of different cultures produce similar stories not because they share similar minds, but because they share similar brains.

And those brains are made for superheroes. Here’s why …

Instead of mapping monomythic plot formulas, studies over the last two decades have focused on defining what kinds of ideas are most easily remembered and therefore more likely to be retold. Intuitive ones, ideas that meet our expectations about reality, are harder to remember than ones that violate them. Counter-intuitive ideas require more attention to mentally process and so make a longer lasting impression. Or they do up to a point. Too many counter-intuitive elements and remembering becomes harder again. So, as Justin Barrett and Melanie Nyhof conclude, a being who “will never die of natural causes and cannot be killed” is easier to recall than a being who “requires nourishment and external sources of energy in order to survive” and also easier to recall than a being who “can never die, has wings, is made of steel, experiences time backwards, lives underwater, and speaks Russian.”

In 1994, Pascal Boyer called the conceptual sweet spot the “minimal counterintuitive” or MCI, and a range of research has refined the definition. Ara Norenzayan and his co-authors found that Brothers Grimm tales with two to three counterintuitive elements received more hits on Google searches than Grimm tales with one or none and tales with more than three. Barrett looked at seventy-three folktales and found 79% included exactly one or two counter-intuitive elements. Joseph Stubbersfield and Jamshid Tehrani’s study of the contemporary “Bloody Mary” urban legend found that Internet versions averaged between two and two and a half MCI elements. Lauren Gonce and her co-authors also found that context matters, since counter-intuitive items presented on a list fare worse than intuitive ones (“singing bird” is easier to memorize than “flowering car”), and M. Afzal Upal defines that relevant context in terms of story coherence, showing that study participants recall a MCI element only if it makes sense of the events surrounding it.

Like Campbell’s monomyth, minimal counter-intuitiveness also describes superheroes. According to Hal Blythe and Charlie Sweet, the prototypical character has inhuman powers, but those “powers are limited” and the individual is “human,” striking the optimal MCI balance. Stan Lee summarized Marvel’s formula in a 1970 radio interview even more precisely: “these are like ‘fairy tales’ for grown-ups, but they were to be completely realistic except for one element of a super power which the superhero possessed, that we would ask our reader to swallow somehow.”

Other comics superheroes tend to violate only one real-world expectation too: Flash moves inhumanly fast; Hawkgirl has wings; Plastic Man’s body is malleable. When a character has more than one counter-intuitive quality, those qualities tend to derive from a single, unifying concept. The bald-headed Professor X has the mental powers of telekinesis and telepathy. The Wasp shrinks to the size of a wasp, flies like a wasp, and stings like a wasp. Spider-Man has the proportional strength of a spider, climbs walls by adhering to vertical surfaces like a spider, and even has “spider senses”—an unrelated ability made to conform to the MCI conceit by adding “spider” as an adjective.

When a superhero violates MCI, it is most often through narrative evolution rather than original concept. Although Superman can fly, shoot lasers from his eyes, and even travel backward in time, Siegel and Shuster’s original had only advanced muscles. Similarly, Wolverine had no mutant healing powers when introduced in 1974, and Lee and Kirby didn’t add force fields to Invisible Girl’s abilities until Fantastic Four #22. Finally, while one character possessing multiple superpowers violates MCI, a team of superhumans does not. An immortal, winged, steel, time-reversing, water-breathing Russian-speaker is maximally counter-intuitive, but a comic book that includes Superman, Angel, Colossus (who also speaks Russian), Merlin, and Aquaman might merely be “bizarre” (a category Barrett and Nyof distinguish from MCI).

Not only does the superhero character type demonstrate MCI, so does the overall world and story contexts. Although superheroes violate a range of natural laws, Joseph Witek still defines superhero stories as naturalistic because the “depicted worlds are like our own, or like our own world would be if specific elements, such as magic or superpowers, were to be added or removed.” The cohesive nature of superhero stories would also place them in Upal’s “Coherent-Counterintuitive” category because the MCI superpower “is causally relevant because it could allow a reader to make sense of the events to follow.” A traditional superhero story does not simply include a character with a superpower, but features the superpower as the means for resolving the central conflict. Comics writer Dennis O’Neil argues:

“A writer fails the genre when a story depicts superheroes who are weak or do not use their powers. What makes a character interesting (both superheroes and other types of characters) is what he does to solve problems. You give him a knotty situation, and he gets out of it. Well, by definition, superheroes use extraordinary physical means … [we] respond to exhibitions of power. That is what a superhero is.”

MCI then defines the superhero character, the superhero world, and the superhero plot.

Although MCI was coined to explain religious concepts, subsequent studies suggest that superheroes in particular demonstrate MCI and so benefit more than other MCI-character types and narratives. For one of Barrett and Nyhoff’s 2001 experiments, participants read a story about an inter-galactic ambassador visiting a museum on the planet Ralyks. The museum featured eighteen exhibits, six with MCI qualities that are also found in superhero comics: Superman’s supervision; Wolverine’s mutant healing; the Blob’s immovable force; Kitty Pryde’s and Vision’s intangibility; Multiple Man’s duplication; and the Watcher’s omniscience. Barrett and Nyhof also bookend their article with references to the contemporary folklore of the part-goat Chivo Man because “a part-animal, part-human creature violates one of our expectations for animals while maintaining rich inferential potential based on pan-cultural category-level knowledge.” Part-animal, part-human characters are also one of the most common naming tropes in superhero comics.

The “Aesop-like fables” created for Upal’s study also reproduce superhero tropes. Of the six MCI qualities contained in the three “Coherent-Counterintuitive” stories, five duplicated superheroes: a “steel-man,” a “wing-man,” an “invisible man,” an “all-seeing woman,” and a “man who could fly and loved helping others.” The “IncoherenCounterintuitive” examples contained only one superhero trope, which appeared in two stories: a woman and then a man both “made of iron.” Upal replaced the previous tropes with non-superhero variants: “a man who had feet instead of hands,” a “villager who could bend spoons with his eyes,” and “a woman from a neighboring village who had ten heads.” Because the coherent and the superheroic coincide, and because the incoherent and the non-superheroic coincide, Upal’s experiment texts further suggest the intrinsic nature of superhero powers as cohesion-producing story elements.

The fact that both Upal’s and Barrett and Nyhof’s studies reproduced superhero character types also makes the researchers unknowing participants in a larger cultural study. The museum beings and Aesop-like characters could be examples of convergent evolution—meaning their authors duplicated Superman’s X-ray vision and the X-Men mutant Colossus’ steel flesh independent of direct influence—or the authors absorbed superhero characters and characteristics unconsciously and reproduced them unknowingly.

Either way, the experiment texts taken as cultural artifacts reveal superheroes as especially fit cultural competitors—due to their apparent pan-cultural appeal.

June 20, 2017

Evie Wyld and Joe Sumner’s “Everything is Teeth”

“It’s not the images that come first,” writes Evie Wyld in the opening sentence of her 2016 graphic memoir Everything Is Teeth. Wyld goes on to describe the sounds and smells of her childhood memories, but her first statement is also a metafictional nod to her collaborative process. Her cover credits artist Joe Sumner not as co-author but as illustrator in a font roughly half the size of Wyld’s, proportions that indicate that the story—the memoir content—is Wyld’s. And it is. At least on the surface. But Sumner’s images—even though they come second collaboratively—produce a far more complex and compelling work than if the memoir were Wyld’s alone.

Sumner interprets Wyld’s words, and so her childhood world, in three scales. He renders the six-year-old Evie and her family members in traditional cartoon style: their heads and facial features are enlarged to impossible proportions, and their density of detail is minimal. Their environments, however, appear roughly naturalistic: trees, buildings, streets, even actors on TV screens have more realistic shapes and less simplified detailing. But the highest level of naturalism, at times achieving photorealism, Sumner reserves for images of sharks: the core subject of the memoir, the “something that lurks beneath the surface”.

Although contrasting, the two styles Sumner selects for characters and setting are a comics norm, common since Hergé‘s The Adventures of Tintin and Osamu Tezuka’s Astro Boy: cartoonishly simplified human figures who people comparatively detailed worlds. But not only does the realism of Sumner’s sharks exceed those norms, he often renders them within shared images to emphasize the impossible contrast.

Wyld’s opening sentence is offset by a country landscape and idyllic harbor—with the meticulous gray tones of a protruding fin shattering the flat black lines of the water’s surface. As the narrating Wylde alludes to undrawn stories about frightened relatives being alone on the water, Sumner instead depicts Evie discovering the simplistically drawn triangle of a shark tooth and carrying it home to show her family. The flat object only takes on shades of depth when it is part of the living, underwater animal.

Sharks are literally otherworldly. Their presence is not only an intrusion into Evie’s childhood reality, it undermines that baseline, revealing it be artificial, a willful illusion of simplicity that can’t be maintained in the presence of real-world threats. When Evie discovers the book Shark Attack!, its vivid renderings introduce the memoir’s first use of color beyond Sumner’s previously subdued yellows and blues. The pages come alive with a literal splash of red. Although Wyld describes a shark survivor’s torso-length scars as “a cartoon apple bite”, Sumner achieves the opposite effect: a photorealistic rendering of the horror that obsesses the child.

Wyld’s verbal images are simple and striking, too. Not only do sharks overturn rafts with “their shovel snouts” and a gored victim feel himself “loose in your skin suit”, but the mundane world is equally eloquent, her father’s skin “milk-bottle white” and her hair turning to “hot bread” in the sun. But nothing is more vivid than Sumner’s underworld of sea life, and the horror of that world proves to be much deeper than any sea.

Even little Evie seems to experience her shark obsession in relation to the mysterious, unexplained violence that lurks just beneath the adult world. She suffers visceral nausea at the family’s killing of a pregnant shark, even as Sumner draws her carrying two of the “puppies back home for frying”. Her father’s inexplicable work life and her mother’s casual insomnia are depths Evie can’t begin to fathom. Two pages after declaring a shark survivor to be “the greatest living man”, Evie’s brother comes home bloodied by bullies, a pattern that continues for much of his adolescence.

Relief seems to come with age, when Evie notices her brother “has become a foot taller than” their mother, but then aging becomes the ultimate threat. Sumner renders the death of Evie’s father in four, full-page images, textually juxtaposed with the now-adult Evie recalling the shark survivor and retroactively understanding the shark not as a monster but a “benign” if “indifferent” force. Her elderly father sits in a lawn chair, then in a hospital bed, until finally only his hat and sunglasses rest on a table framed in white on a black two-page spread.

Aside from two glimpses back into her childhood shark book, the world remains simple. Unlike the swimmer, her father’s struggle with death is a wordless cartoon. If death is the something lurking beneath the surface, it never breaks the water to reveal itself. It never provides the sufferer with a heroic struggle rendered in a more-real-than-real style. Even on his deathbed, her father cannot escape his caricature proportions: an absurdly large head with an absurdly large nose, only now framed in white rather than black lines of hair.

Wyld recounts only one incident in which she wasn’t present herself. “My parents,” she writes late in the memoir, “went deep-sea fishing a long time before I was born.” After catching fish after fish, everyone stopped and “watched mutely as a tiger shark, pale blue and clean, bigger than the boat, passed under, its fin skimming the hull.” Sumner draws the passengers in a thin strip at the top of the two-page spread, while giving nearly 4/5ths of the page space to the black water and the two largest and most fully detailed drawings of sharks in the memoir.

This oddly pivotal moment not only breaks chronology for the first and only time in the narrative, it also places Wyld’s text into the same ambiguous relationship to events as Sumner’s drawings. Like Sumner who receives Wyld’s memories only through her telling, Wyld received her parents’ memories of the fishing trip through their telling. But, like Sumner, Wyld goes beyond her source, rendering the story in her own vivid style. Her eloquence makes it her own—just as Sumner’s artistry makes Wyld’s story his own, too.

[The original version of this and my other recent reviews also appear in the comics section of PopMatters.]

June 12, 2017

When Did the Hulk Become the Hulk?

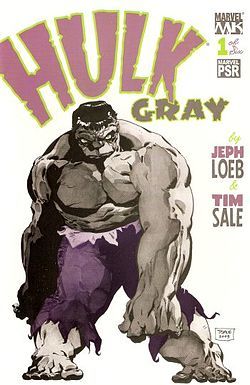

After appearing gray-skinned in his premiere issue, the Hulk inexplicably turned green in his second. Though the color change had more to do with printing costs than storylines, the gray Hulk had a personality distinctly different from his later version. Marvel writers eventually retconned a distinct and separate character into the premiere issue, turning the gray Hulk into Gray Hulk AKA Joe Fixit.

When recalling creating the Hulk years later, Lee described the canonical green version: “I just wanted to create a loveable monster—almost like the Thing but more so … I figured why don’t we create a monster whom the whole human race is always trying to hunt and destroy but he’s really a good guy.”

But even after The Incredible Hulk #1, the original Hulk was not loveable and was no good guy. He was a barely controlled monster who posed as a much of threat to the world as the supervillains he fought. After his original six-issue run and a few appearances in other titles, the Hulk’s cancelled series was renewed in 1964 as one of two ongoing features beginning in Tales to Astonish #59, with artist Steve Ditko replacing Dick Ayers for pencils beginning #60, and Jack Kirby co-penciling with multiple artists beginning #68. Stan Lee was credited for all writing, but because of the so-called “Marvel Method” much of the uncredited and unpaid co-writing fell on the pencilers.

The 1964 Bruce Banner no longer uses his Gamma Ray device to transform into the Hulk, and when Giant-Man comes searching, Banner thinks, “So! The Avengers are still seeking the Hulk, eh? Will they never leave him in peace?”, reflecting the early stages of Lee’s revision. The Hulk himself later laments: “There is nothing for Hulk—nothing but running—Fighting! Nothing—” (#67). The character is still antagonistic and can take “off like a missile”, but he saves Giant-Man when both are targeted by an atomic shell, also throwing it to explode far from the nearby town (#59). The Leader, the primary antagonist from #62–75, was “an ordinary laborer” until yet another “one-in-a-million freak accident occurred as an experimental gamma ray cylinder exploded” transforming him into “one of the greatest brains that ever lived” (#63). Also, as earlier, Banner gains control of the Hulk’s body for several episodes, continuing the struggle of the 1962 series.

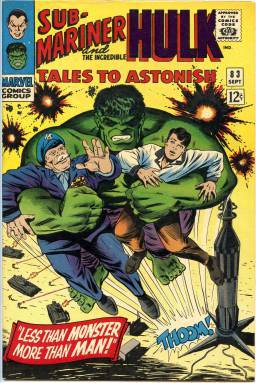

After the January 1966 issue, however, the premise changes. When the military fires Banner’s experimental “T-Gun,” the Hulk is sent to “some far distant future,” a “dead world” in which Lincoln’s memorial statue sits in the ancient ruins of Washington, D.C. (#75). A future commander declares: “We cannot allow a destructive, rampaging brute to run amok in our land!” (#76). This “grim, ominous war-torn world of the far future” recalls Kennedy’s 1963 “war makes no sense” refrain, and when the Hulk returns from it to his own time, he settles into a new, toddler-like personality, no longer posing a threat unless attacked.

Moreover, as with the Thing and his love interest Alicia, Banner’s girlfriend, Betty Ross, views the Hulk in transformative light: “His arms—so huge—and brutal—but yet, so strangely gentle—!” (#82). Although he has brought her to an isolated cave, she adds: “It’s strange! I find I’m not afraid of him any longer! As powerful, and as unpredictable as he is … I can’t help feeling he’s not truly evil!” (#83).

Even General Ross, who has hated and hunted the Hulk since his debut, changes attitude: “The strongest … most dangerous being on Earth … but my daughter tells me he rescued her … tells me she loves him …! And yet … somehow … I find myself beginning to understand”. When the military test fires another of Banner’s weapons, an “anti-missile proof” missile and so “the greatest weapon of all!” (#85), the Hulk prevents it from destroying New York.

With the Hulk’s secret identity no longer a secret, Betty declares: “Now there can be no doubt! The Hulk isn’t a monster—he never was! He was always you!” (#87), and her father now asks for Banner’s help in stopping the next menace and praises the Hulk because “he saved us—from our own folly!” President Johnson sends General Ross an executive order: “If, in your opinion, the Hulk is no longer a menace, you are authorized to grant him full and immediate amnesty, clearing him for all guilt, or suspicion of same,” but because a villain tricks the Hulk into a rampage Ross shreds the order (#88).

Though the Hulk remains an outcast, the ongoing narrative permanently shifted. Like the X-Men who are also distrusted and pursed by government figures, readers understand the government to be definitely wrong. By losing its monstrous ambiguity, the Cold War superhero formula regained its original Golden Age status of misunderstood hero.

June 5, 2017

Rereading The Incredible Hulk #1-6 (1962)

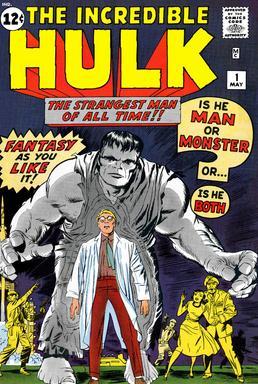

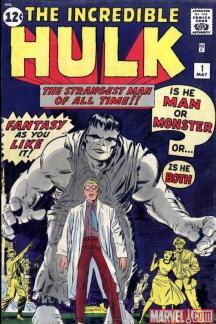

Stan Lee predicted in his original 1961 Fantastic Four synopsis that the unpredictable and monstrous Thing would prove to be the most interesting character to readers. He was right—so much so that after four issues, Marvel premiered a new title that featured a main character based on the Thing:

The first cover of The Incredible Hulk makes the monster motif explicit, asking “Is he man or monster or … is he both?” Lee combined the standard superhero alter ego trope with the uncontrolled transformations of a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and Kirby models the Hulk on Boris Karloff in the 1931 Frankenstein. Like those mad scientists, Dr. Bruce Banner is “tampering with powerful forces,” only now his hubris transforms himself into his own monstrous creation. The opening panel features “the most awesome weapon ever created by man—the incredible G-Bomb!” moments before its “first awesome test firing!” Kirby draws its creator with a “genius” signifying pipe as he takes “every precaution,” even as General Ross insults him for cowardly delays. Though Banner risks his life to save Rick, a teenager who has driven onto the bomb site, that kindness is erased by the Hulk who, after his first Geiger-counter-triggering transformation, swats Rick aside, uttering his first words: “Get out of my way, insect!” Lee likens him to a “dreadnought,” the twentieth-century’s most massive battleships, and soon he is speaking like a supervillain, “With my strength—my power—the world is mine!,” and threatening to kill Rick to keep his identity a secret.

The first issue would be a complete repudiation of the superhero formula if not for the late entrance of another “brilliant” scientist-turned-radioactive-monster; the Soviet Union’s Gargoyle captures the Hulk, threatening the balance of power: “If we could create an army of such powerful creatures, we could rule the Earth!” Like the Hulk, the Gargoyle is controlled by no nation, savoring that his “cowardly” comrades and “some day all the world will tremble before” him.

The Gargoyle is stopped not by the Hulk’s might, but Banner’s “milksop” kindness, reversing the Clark Kent trope that had defined the superhero genre for two decades. The crying Gargoyle would “give anything to be normal!” as Kirby draws him shaking his fist at a portrait of Khrushchev because he became “the most horrible thing in the world” while working “on your secret bomb tests!” As a result, he accepts Banner’s offer to cure him “by radiation,” and in turn destroys the Soviet base and rockets Banner and his sidekick back to the U.S.: “So we’re saved! By America’s arch enemy!” Although Banner hopes for the end of “Red tyranny,” he remains “as helpless as” the Gargoyle against his own “monster”.

In addition to changing from gray to green, in the second issue, the Hulk seizes control of an alien spaceship to use it for his own purposes: “With this flying dreadnaught under me, I can wipe all of mankind!” and it is again Banner, using his “Gamma Ray Gun” invention, who stops the alien invasion.

These are not the tales of a standard dual-identity superhero, but a Clark Kent battling both external threats and his own supervillainous alter ego. Steve Ditko inked Kirby’s pencils for the second issue, cover-dated July 1962, a month before the premiere of Lee and Ditko’s Spider-Man in Amazing Fantasy #15. Ditko’s Hulk bore an even greater semblance to Karloff, and now Peter Parker looked like a younger version of Bruce Banner. The Hulk does not begin to resemble a superhero until the following month.

In the third issue, the military attempts to destroy the Hulk by launching him into the same radiation belt that created the Fantastic Four, but instead his transformations, which were previously trigged by nightfall, become unpredictable. Rick briefly gains hypnotic power over the “live bomb” of the now golem-like Hulk, evoking another admonitory fable: “It’s too much for me! I’ve got the most powerful thing in the world under my control, and I don’t know what to do with it!”

Kirby and Lee could not settle on a clear premise, with the Hulk changing personalities and transformation plot devices every other issue. In the fourth issue, Banner invents a self-radiating machine in order to “regain the Hulk’s body—but with my own intelligence,” which, though seemingly successful, creates a “fiercer, crueler” version of Banner inside a Hulk who is still “dangerous” and “hard to control.”

The new Hulk no longer tries to kill Rick, but now speaking like the Thing, he tells him to “Shut your yap” and to “get outa my way!” before foiling the Soviets’ next attempt to capture him and again build “a whole army of warriors such as you!” Though he prevents another invasion, this time by an underground race led by an ancient immortal tyrant, the Hulk ends his first adventures in the following issue articulating his defining nuclear allegory: “Let ‘em all fear me! Maybe they got reason to!” In the issue’s second story, he thwarts a Chinese Communist general, and yet the Hulk insists that “the weakling human race will be safe when there ain’t no more Hulk—and I’m planning on being around for a long time!!!”

By the sixth issue, the last of the original, one-year title run, the Hulk has reverted to a supervillain and considers teaming-up with an invading alien against the human race “to pay ‘em all back!” Though the Hulk ultimately defeats the alien, winning a pardon for his past crimes, Banner has less and less control of his transformations, suffering delayed and partial effects with Banner briefly retaining some of the Hulk’s strength and, more bizarrely, with the Hulk briefly retaining Banner’s face. Rick concludes: “The Gamma Ray machine—it grows more and more unpredictable each time it’s used! If Doc has to face it again—what will happen next time?”

“Next time” was delayed by over a year, after the Cuban missile crisis led to a paradoxical drop in Cold War anxieties. After a few appearances in other titles including The Avengers, the Hulk and his cancelled series were renewed in 1964 as one of two ongoing features beginning in Tales to Astonish #59. Both the Gamma Ray machine and Banner’s unpredictable transformation were forgotten, and the Hulk soon evolved into the canonical version of the character: a well-intentioned but toddler-minded creature misunderstood and mistreated by the authorities.

May 29, 2017

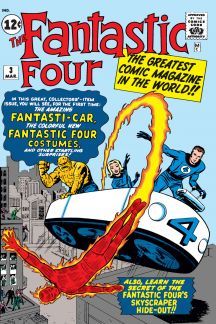

Rereading The Fantastic Four #1-9 (1961)

Stan Lee suggested a central “gimmick” in his original 1961 synopsis for the Fantastic Four:

“let’s make The Thing the heavy—in other words, he’s not really a good guy … Let’s treat him so the reader is always afraid he will sabotage the Fantastic Four’s efforts at whatever they are doing—he isn’t interested in helping mankind the way the other three are … the other three are always afraid of The Thing getting out of their control some day and harming mankind with his amazing strength … The Thing doesn’t have the ethics that the other three have, and consequently he will probably be the most interesting one to the reader, because he’ll always be unpredictable.”

Although Ben Grimm is an “ex-war hero,” Lee describes him as “surly,” “unpleasant,” and “brutish,” even before radiation transforms him “in the most grotesque way of all,” making him “more fantastically powerful than any other living thing.” Early issues emphasize the same qualities. While Kirby and other artists had previously drawn superheroes as uniformly handsome, the Thing is “a walking nightmare” with a misshapen body and a face as unattractive as Moleman’s. In the second issue, Sue whispers to Reed: “Sooner or later the Thing will run amok and none of us will be able to stop him!” and Ben, “a juggernaut of destruction,” confesses: “sometimes I think I’d be better off—the world would be better off—if I were destroyed!” Many readers felt the same about nuclear weapons.

Even aside from the Thing, Kirby and Lee portrayed the Fantastic Four as superheroes who produce rather than assuage anxiety. Kirby opens the first issue with an image of frightened pedestrians pointing at the flare Reed has fired to gather the team; police officers remark that “the crowds are getting’ panicky!” and that “[r]umors are flyin’ about an alien invasion!” During their origin sequence, Johnny calls both Ben and Reed “monsters,” before uncontrollably transforming into a Cold War version of the pre-Code Human Torch and accidentally starting a forest fire. “Together,” declares Reed, “we have more power than any humans have ever possessed,” a familiar superhero refrain now given new nuclear-era meaning.

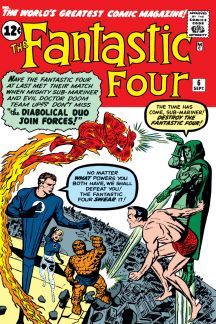

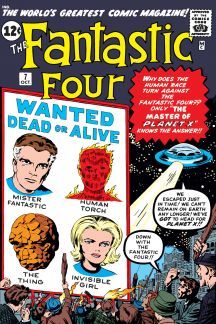

The second issue opens with a three-page sequence of the Fantastic Four committing acts of sabotage, causing news agencies to declare them “public enemies” and “the most dangerous menace we have ever faced!”—an opinion repeated in #7 when a “hostility ray” turns the world against them as “four monsters,” “the worst menaces ever to threaten this land!” The acts of sabotage were actually performed by shape-shifting Skrulls, and though the Fantastic Four are not powerful enough to defeat “the mighty invasion fleet menacing Earth,” they end the “stalemate” by showing the Skrulls other Jack Kirby drawings from Strange Tales and Journey into Mystery and so convincing them that humans have armies of “monstrous” warriors ready to protect them. The first cover features one such monster, only now the Fantastic Four serve as monster-fighting monsters trying to protect the city from it—a defining introduction for the MAD-era superhero type.

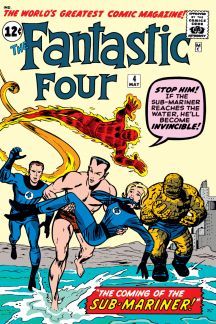

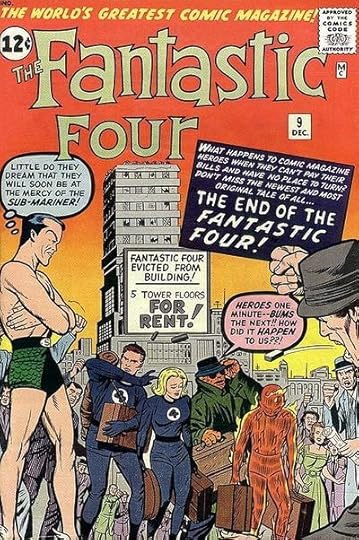

The Fantastic Four’s early antagonists evoked similar atomic fears with striking repetition. Moleman targets “every atomic plant” (#1), the Skrulls attack a “new rocket” test site (#2), Miracle Man steals an “atomic tank” (#3), and the 1940s Sub-Mariner vows revenge on the human race when he finds his underwater city destroyed: “The humans did it, unthinkingly, with their accursed atomic tests!” (#4). Dr. Doom, after bringing “forth powers he could not control” (#5), stokes the Sub-Mariner’s hatred, describing “that monster of a bomb” that destroyed his civilization (#6). The Thing mistakes an alien spaceship for “a new missile test,” while on Planet X, “Driven by fear and panic, our people are turning against each other! Soon nothing will be able to stop the riots … nothing except the doom which is hurtling toward us!” (#7). Finally, the Puppet Masters controls his victims by carving their likenesses in “radioactive clay” (#8).

Lee’s “gimmick” to include a bad guy within a team of good guys altered the standard superhero plot structure by splitting the heroes’ focus between fighting external threats and containing an internal one. Alan Moore, reading The Fantastic Four #3 as a child, had “the impression that [the Thing] was on the verge of turning into a full-fledged supervillain,” not “the cuddly, likeable ‘Orange Teddy-bear’ of later years. Stan Lee recalls writing the character in a 1981 interview:

“I tried to have Ben talk like a real tough, surly, angry guy, but yet the reader had to know he had a heart of gold underneath … People always like characters who seem very powerful yet, you know they are very gentle underneath and you know they would help you if you needed it.”

Lee’s recollection is of the later characterization, not the Thing of 1961, whose surliness was not a disguise. When Ben says to Sue in the first issue, “Now let’s go find that skinny, loud-mouthed boy-friend of yours!”, Lee scripts her response at face value: “Oh, Ben—if only you could stop hating Reed.” According to Lee’s original synopsis, Ben “has a crush on Susan,” “is jealous of Mr. Fantastic and dislikes Human Torch because Torch always sides with Fantastic,” and “is interested in winning Susan away from Mr. Fantastic.”

Despite Lee’ stated intention, his and Kirby’s rendering and readers’ perceptions of Ben grew more sympathetic. Ben complains to Reed: “At least you’re human! But how would you like to be me?” and Sue herself is sympathetic: “Thing, I understand how bitter you are—and I know you have every right to be bitter!!” When Ben returns to human form for a few moments after passing through the radiation belt again, Torch consoles him too: “She’s right, pal! That was just a start!” In #3, despite renewed fighting with Torch, Ben intervenes to save Reed’s life: “Reed can’t dodge those dum-dums forever, I gotta do something!!”

By #6, Kirby and Lee are no longer portraying overt conflict between the characters, and with #8—coincidentally on sale during the Cuban missile crisis—Ben’s “crush” ends and his character is redefined by the introduction of an alternate love interest. The Puppet Master’s blind step-daughter, Alicia, disguises herself as Sue, fooling all of Sue’s male teammates. Though Ben suffers another temporary transformation to human form, Alicia’s love is permanently transforming: “This man—his face feels strong and powerful! And yet, I can sense a gentleness to him—there is something tragic—something sensitive!” The Thing transfers his affection to Alicia, who reciprocates and humanizes his previously inhuman character: “the clinker is—she likes me better as the Thing!” In the following issue, Alicia calls Ben “my white knight! You are good, and kind, and you will never desert your friends when they need you most!”, prompting Ben to hug his teammates: “us white knights don’t desert their companions in arms! I’m with ya, gang!”

Marvel began with a Cold War plot gimmick that resulted in unplanned character complexity and then ad hoc revision, producing the unified family-like Fantastic Four that would define the series and a new superhero character type that would define the Marvel universe.

Chris Gavaler's Blog

- Chris Gavaler's profile

- 3 followers