Chris Gavaler's Blog, page 50

January 2, 2017

Black in the Golden Age

Trump supporters long for a Golden Age. “I used to sleep on my front porch with the door wide open, and now everyone has deadbolts,” one guy told Republican pollster Frank Luntz early in the primary race. “I believe the best days of the country are behind us.” So Trump gave him what he wanted, what The Atlantic‘s Ester Bloom calls “a sugar pill coated in nostalgia.” Actually, Trump didn’t give him anything. He just sold him a slogan. “We know his goal is to make America great again,” another supporter told pollsters. “It’s on his hat.” And now that time-travel hat is headed to the White House. “But,” Bloom asked over a year ago, “to what era does he intend to take the nation back? And what would that look like, practically speaking?”

Well, superhero comics have a very specific Golden Age. It runs from the 1930s to the 1950s. I write about it in my forthcoming book Superhero Comics. (I didn’t choose the title, but Trump has taught me that simplicity sells.) So what did the superhero Golden Age look like? That depends on who swallows the sugar pill. Practically speaking, it’s not so golden if you weren’t a white guy in tights. So adjust your hats, and let’s take a peek …

Superhero comics in the pre-Code years of the 30s, 40s, and early 50s are dominated by a lack of black representation and punctuated by instances of extreme racist caricature. “Racism was built into the foundations of entire once-popular genres, especially jungle comics … and war comics,” writes Leonard Rifas, noting the predominance of “early American comic books that show white characters in dominant positions of over nonwhite domestics, natives, or sidekicks”.

Superhero comics in the pre-Code years of the 30s, 40s, and early 50s are dominated by a lack of black representation and punctuated by instances of extreme racist caricature. “Racism was built into the foundations of entire once-popular genres, especially jungle comics … and war comics,” writes Leonard Rifas, noting the predominance of “early American comic books that show white characters in dominant positions of over nonwhite domestics, natives, or sidekicks”.

The pattern begins with the first recurring black character in superhero comics, Lothar, created by Lee Falk for his daily newspaper strip Mandrake the Magician. For the June 11, 1934 debut, artist Phil Davis drew Mandrake’s sidekick in what would be the character’s signature wardrobe: shorts, cummerbund, lion-skin sash, and fez. Although in the second installment Lothar introduces his “Master” in what was termed General American English in the 30s, before the end of the year, Lothar’s speech had devolved into ungrammatical fragments: “Three men fight lady. Is bad. Me almost get mad.” The “lady” is Barbara, Mandrake’s white love interest, who then dubs Lothar “My watchdog”.

As Mandrake continued its newspaper run, readers witnessed Jesse Owens’ Olympic and Joe Louis’ boxing victories, as well as the appointment of the first African American federal judge, William H. Hastie. But five years after his debut, Lothar’s speech has not improved; after rowing his master through a swamp and holding an umbrella over Barbara’s head, Lothar faces the ghosts of two pirates: “Me scared—but me sock!” Although identified as the prince of several African tribes, Lothar chooses to live in the United States as an ambiguously slave-like servant to a white, Orientalist magician.

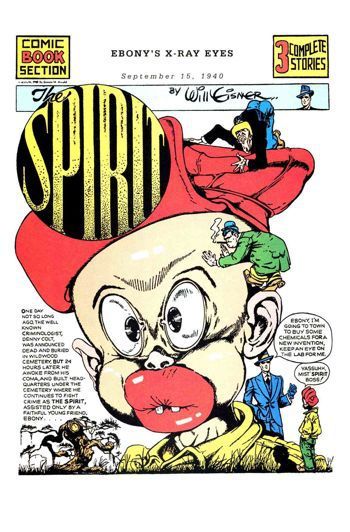

The following year, Will Eisner introduced newspaper readers to another crime-fighting sidekick, The Spirit’s Ebony White. Nonwhite sidekicks were a standard outside of comics, with the Lone Ranger’s Tonto and the Green Hornet’s Kato speaking broken English on the radio, and The Spider’s “turbaned Hindu” valet Ram Singh speaking in faux middle English in the pulps: “Fortunate it is that thy servant obeyed his orders”.

Eisner introduced Ebony as an unnamed taxi driver in the first The Spirit newspaper insert on June 2, 1940. In the second, he apologizes for speeding: “Sorry, boss, dis car jes’ nachelly speeds up when ah drives past Wildwood cemetery!!” In the third, he acquires his name and becomes the Spirit’s “exclusive cabby”, though by July, the Spirit has his own car, and Ebony is his “assistant” in August. Ebony’s face dominates the entire splash page the following month: bulging cheeks, round and crossed eyes, a tiny upturned nose, two protruding teeth, and, most prominently, enormous red lips—a cartoon embodiment of blackface minstrelsy. Eisner described the caricature as “a product of the times”.

Black characters in comic books were rarer. Joe Shuster drew no African Americans in the first three years of Action Comics, and Harry G. Peter drew only four in Wonder Woman’s first two years: a train porter, two hotel workers, and an elevator operator. The first three speak in slightly abbreviated General American English: “Yes, Ma’am! Suitcase comin’ up! This suitcase is heavy! Must be fulla books!”, but the last William Marston scripts: “Bell done buzzed f’om dis floah—but dey ain’ nobody heah!”

Analyzing the seventy-eight issues of Captain America’s 1940-1954 titles, Richard A. Hall counts only two African Americans: a cowering and superstitious butler named Mose in 1942 and a member of the adolescent Sentinels of Liberty named Whitewash a year earlier. Both are rendered in a style Hall terms “Amos and Andy-esque,” referencing one of the most pervasive and demeaning representations of African Americans by white authors of the period. Charles Nicholas Wojtkoski’s rendering reproduced the enormous lips of 19th century cartoons, the same tradition Eisner followed.

Beginning in 1941, the zoot-suit-wearing, harmonica-playing, watermelon-eating Whitewash Jones regularly appeared in Young Allies, which ran twenty issues before being cancelled in 1946, and in ten issues of Kid Comics from 1943-46. Although Hall concludes that “There were literally no non-white heroic figures during this period”, Whitewash, while fulfilling the role of comic relief through racist caricature, is also the first African American hero in superhero comics.

In the Young Allies premiere, Wojtkoski and writer Otto Binder present him as an equal member of the “small band of daring kids”, one who wrestles Nazi spies, discovers a trail that leads to the Red Skull’s cave, saves team leaders Bucky and Toro by triggering a cave-in, and saves the entire team by discovering that their drinks have been poisoned. When a military officer presents “each with a distinguished service medal” for “exceptional bravery in action,” Wojtkoski draws Whitewash beside Toro and in front of two other white members, and for the chapter four splash page, contributing artists Joe Simon and Jack Kirby place Whitewash at center, pinning Hitler with his team members. In one panel, the character leads the team on bicycles stolen from German soldiers.

Yet Whitewash also exposes the team as stowaways and is chided for his shocking “ignorance”. He is, however, no more comic than his teammates. Though Whitewash is afraid to enter the cemetery, Knuckles dives head-first behind a bush at the sound of an owl. Whitewash trips over his own rifle, but only because Tubby backs into him. Whitewash complains about walking, while Tubby complains about hunger and Jefferson Worthington Sandervilt about the smell of fish. Sandervilt also voices fear, “My. What a harrowing experience!” before Whitewash, “Is dey gone?” Arguably all four of the secondary Young Allies characters are sidekicks to Bucky and Toro, and so are not independently heroic themselves. But Whitewash, while a grotesque amalgam of African American caricatures both visually and verbally, is not singled out for comic relief and often contributes more significantly than his white teammates.

Despite these exceptions, nonwhite protagonists remained a rarity in pre-Code comics, superhero-oriented and otherwise, and black creators were even rarer. Jackie Ormes is considered the first African American woman cartoonist, with her 1937 comic strip Candy running in the Pittsburgh Courier, a nationally distributed African American newspaper. Beginning in the early 40s, Alvin Hollingsworth drew for Holyoke’s Cat-Man Comics, as well as “Captain Power” in Novack’s Great Comics, female Tarzan knock-off “Numa” in Fox Feature Syndicate’s Rulah, Jungle Goddess, and “Bronze Man” in Fox’s Blue Beetle. In 1947, Philadelphia publisher Orrin Cromwell Evan’s one-issue All-Negro Comics featured artist George J. Evan, Jr.’s “Lion Man,” the first African American superhero by black creators and one, the publisher explains in his introduction, intended “to give American Negroes a reflection of the natural spirit of adventure and a finer appreciation of their African heritage”.

Matt Baker achieved the highest level of success and, indirectly, notoriety in the early comics industry. Alberto Becattini and Jim Vabedoncoeur, Jr. index over six hundred credits for Baker in roughly 150 different titles. Working through the Iger Studio, which had previously included Will Eisner and Jack Kirby, Baker began his career on “Sheena, Queen of the Jungle” and “Sky Girl” in Fiction House’s Jumbo Comics in late 1944, before expanding to “Skull Squad” in Wings Comics and “Wambi the Jungle Boy” in Jungle Comics. Baker rendered his African tribesman in the same relatively realistic style as his white characters, with no hint of Eisner’s and Wojtkoski’s racist cartooning.

Baker’s off-page experiences were less integrated. A fellow Iger artist recalled how Baker “would go off on his own” during lunch breaks, “acutely aware of the perceived chasm that separated him” in “an industry almost totally dominated by white males”. Baker’s greatest successes came in his sexualized renderings of women—a style that may have been influenced by Jackie Ormes’ Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger one-panel comics that ran in the African American newspaper Chicago Defender beginning in 1945. After Sheena imitations “Tiger Girl” and “Camilla,” Baker drew Fox Features’ redesigned Phantom Lady as one of his last projects before expanding to freelancing.

While Baker was amassing romance credits in the 50s, Frederic Wertham reproduced his April 1948 Phantom Lady cover in Seduction of the Innocent with the caption: “Sexual stimulation by combining ‘headlights’ with a sadist’s dream of tying up a woman”, and a blow-up of the “objectionable” cover was displayed during the 1954 Senate Subcommittee Hearings into Juvenile Delinquency. Wertham condemned “race hatred” in his testimony (specifically a Tarzan comic in which a “Negro” blinds twenty-two white people, including “a beautiful girl”), but the absence of any mention of Baker in the hearing transcripts is likely due to committee members not knowing that a black man had drawn the images of a scantily-clad white woman. Juvenile Emmett Till would be murdered for flirting with a white woman and his killers acquitted the following year.

[So much for the Golden Age. But maybe Trump supporters have a slightly different era in mind? I’ll continue my search next week.]

December 26, 2016

Fantastic Beasts and American Eugenics

I was invited back to MuggleNet Academia to talk about eugenics and the world of Harry Potter. Given our country’s current Trump-fueled anti-immigrant hysteria, it is sadly much more than a history lesson:

“Ezra Miller, the actor who plays Credence Barebones in Fantastic Beasts, and David Yates have both said in interviews that Rowling’s New Salem Philanthropic Society is largely an allegorical depiction of the Progressive Era eugenics movement in the United States. This chapter of American history — how social engineering know-betters on the political left and right campaigned successfully for sterilization and extermination laws to rid the American gene pool of ‘moron women, sexual deviants, and racial inferiors’ in 31 states — has largely been scrubbed from the history textbooks. It’s more than a little embarrassing for us to learn, after all, that Adolf Hitler modeled his Final Solution, the Holocaust of European Jewry, on tracts, scientific publications, and laws written by Americans with the sponsorship of the Rockefeller Foundation (among others). Not only can it happen here, it started here.

“To discuss American eugenics and how Rowling chooses to give that history lesson as an embedded story within her screenplay, not to mention how some of her historical connections are bizarre and off-base, Keith Hawk and I asked Washington & Lee professor Christopher Gavaler to join us on MuggleNet Academia. Gavaler is the author of On the Origin of Superheroes which largely turns on the subject of eugenics as it was told in the Superman/Ubermensch dramas of the late 19th and early 20th Century UK and US and then in the first superhero comic books. He explained to us how Rowling’s Hogwarts Saga’s Pureblood/Mudblood purity theme is straight up anti-eugenics story-telling — and that in Fantastic Beasts she is picking up where she left off.

“Another mind-blowing conversation on MuggleNet Academia! Here is a link to Professor Gavaler’s article ‘The Well Born’ Superhero’ that we discuss on the show. Enjoy that challenging read before or after you listen to our conversation — and please share your thoughts about the podcast in the comments boxes below!”

The hour-long interview is here (though you might want to skip over the first ten minutes).

December 19, 2016

How to Talk to the Confederacy

Days after the election, President-elect Trump told 60 Minutes that he was “surprised to hear” his supporters were using racial slurs and threatening African Americans, Latinos, and gays. Last week the FBI documented a 6% increase in hate crimes, especially against Muslims. Last month NYC Police Commissioner James O’Neill reported that hate crimes are “up 31% from last year. We had at this time last year 250; this year we have 328. Specifically against the Muslim population in New York City, we went up from 12 to 25. And anti-Semitic is up, too, by 9% from 102 to 111.” When asked why, he said he had “no scientific evidence,” but “you’ve been paying attention to what’s been going on in the country over the last year or so and the rhetoric has increased, and I think that might have something to do with it.”

Ya think?

I live in Lexington, Virginia, and KKK fliers appeared on our front yard the month that Donald Trump accepted the Republican nomination for President. The Confederate flag, which appeared at rallies during Trump’s campaign, is back in view across the country. High school students in Silverton, Oregon displayed it at a Trump rally on Election Day, telling Hispanic classmates: “Pack your bags; you’re leaving tomorrow.” The two students were suspended, which isn’t an option for other post-election Trump supporters waving it in Durango, Colorado, Traverse City, Michigan, St. Petersburg, Florida, Hampton, Virginia, and Fort Worth, Texas.

Trump’s chief White House strategist Stephen K. Bannon is the former head of Breitbart News, which said the Confederacy was “a patriotic and idealistic cause,” and that its flag “proclaims a glorious heritage.” This was posted after the Charleston, South Carolina church shooting, in which white supremacist Dylann Roof murdered nine people. White supremacists have been rallying around the Confederate flag for over a 150 years, but even Trump supported removing it from South Carolina’s statehouse last year: “I think they should put it in the museum, let it go, respect whatever it is that you have to respect, because it was a point in time, and put it in a museum.”I’m not clear what there is to “respect,” but the “point in time” is called the Civil War. If you read the declarations of secession, the South began it for one reason and only one reason.

But instead of a history lesson, I’ve asked Two-Face to give us his opinion about the flag. This is the fifth and for-now-final installment of Two-Face’s politcal cartoons. Because this shit just ain’t funny.

Mr. Two-Face:

Thanks, Mr. Two-Face. Your scarred half sure knows how to keep things simple.

Oh, and here’s a postcard-sized version to mail to friends and family members currently residing in the racist past:

And if you’re a Southerner in need of a symbol of your pride, Unscarred George invites you to display this flag instead:

December 12, 2016

Simplifying American History

History is confusing. There are so many people and places and names, it’s hard to keep it all straight. That’s why it’s important to write history books that everyone can understand. And it’s even more important to write American history books that make Americans feel good about America. Because who wants to read something depressing about your own country?

That’s why former Republican Presidential contender and future Secretary of Housing and Urban Development Ben Carson was so upset about the College Board’s 2014 Advanced Placement history course. It was way too negative. “I think,” said Carson, “most people, when they finish that course, they’d be ready to sign up for ISIS.”

Fortunately, ISIS doesn’t accept college credit for high school courses, even when students earn a top score of 5 on an A. P. exam. The course was endorsed by the American Historical Association, which defended its choice between “a more comfortable national history and a more unsettling one,” but the Republican National Committee still called it a “radically revisionist view of American history that emphasizes negative aspects of our nation’s history while omitting or minimizing positive aspects.”

So the College Board rewrote its history to make it “balanced” (the same word they like so much over at Fox News). It even made the director of education policy at the conservative American Enterprise Institute feel “very comfortable.” That’s not easy to do, especially with a history filled with so much confusing and depressing information.

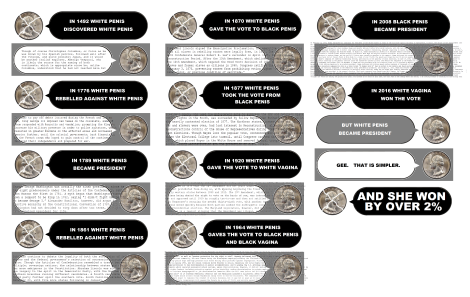

After Donald Trump is appointed President by the Electoral College, a lot of more history books will need to be rewritten to make America great again. That’s not an easy job, so I’ve asked Two-Face to give it a try in this week’s political cartoon. His two-headed view gives him a perfect perspective on American politics (and what better way to understand America than getting acid thrown in your face?).

The trick is to figure out what your readers like most and then rewrite everything around those basic ideas. So based on the 2016 election, what do Americans really care about? The scarred half of George Washington boiled it down to just two things (though the silly, unscarred half is still sorting through all those pesky facts).

Here it is:

WHITE PENIS HISTORY

Like America, it’s still a work-in-progress, but I’m sure Two-Faced George will have even black penis Ben Carson feeling very comfortable soon.

Oh, and here’s a mini version to cut out and use as a cheat sheet when you’re trying to pass your ISIS entrance exam.

December 5, 2016

Reality Check

Americans get a little confused about economics. The U.S. GDP growth rate is at a two-year high, and unemployment is back to where it was before George Bush’s Great Recession, but voters named the economy as their top concern. And then they elected a man who lost $910,000,000 in a single year and declared bankruptcy six times. President-Elect Trump also promises massive tax cuts and massive infrastructure spending, adding $5,300,000,000,000 to the national debt.

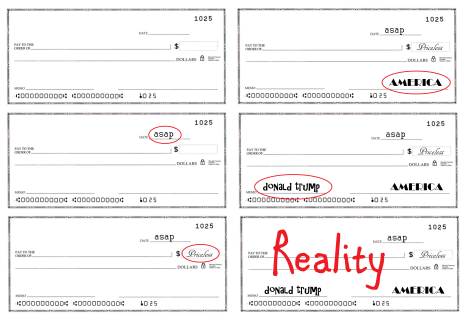

Republicans have been deficit hawks for decades, so the double-talk is especially confusing. That’s why I’ve invited back Batman supervillain Two-Face to give America a little economic crash course. As the election taught us, it’s important to keep things simple, so he’ll focus on the most basic challenge of domestic finance: how to write a check. Mr. Two-Face, like America, will once again be speaking from the scarred half of his head.

How To Write a Check

Thank you for the reality check, Mr. Two-Face.

And if you know any folks having trouble balancing their own realities, please feel free to print and cut these out for personal use:

There’s even a large-print version for all those older Trump voters:

November 28, 2016

Words Fail

Are words necessary?

One of my favorite comics, Alan Moore and Bill Sienkiewicz’s Big Numbers #1 (1990), opens with a wordless eight-page sequence, culminating with some punk kid throwing a rock through a moving train window. On page nine, a sleeping passenger startles from a dream and screams, “AAA! SHIT!” Then the elderly couple seated across from her say, “I don’t think there’s any need to use language.”

Get it? They mean profanity, but Moore means language in general–does a comic book really need it? I’ve been spending my fall semester plunging into a deeper study of the comics form and am finding that some of the very best graphic novels are wordless: Lynd Wards’ Gods Man (1929), Thomas Ott’s R.I.P.: Best of 1985-2004, Renee French’s H Day (2010), Daishu Ma’s Leaf (2015). I teach creative writing fiction in our English department, so it makes my wife (and former department chair) nervous when I say words are just clutter. There are endless exceptions of course, but too often dialogue and captions in comics are visually ugly and narratively redundant. Images can do almost all of the talking.

But when I look at that Big Numbers scene now, I don’t think about comics. I think about our President-elect punk throwing his majority-losing rock through the TV screen of America’s napping leftwing voters.

America: “AAA! SHIT!”

Elderly Trump Voters: “I don’t think there’s any need to use language.”

I responded to the election by creating a political cartoon based on the Batman villain Two-Face, a caricature of myself now that I’ve disavowed all moderate political perspectives in favor of uncompromising leftwing extremism. Since I’m currently drafting a creative writing textbook on creating comics, it’s both cathartic and practical. I’ve spent a lot of time looking at comics art, analyzing the relationships between words and images, style and subject, line and concept, but it’s an entirely different thing to understand those ideas from inside the creative process.

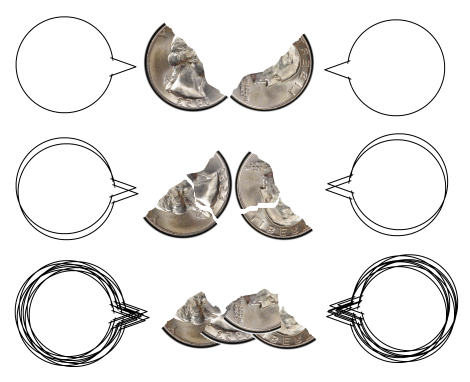

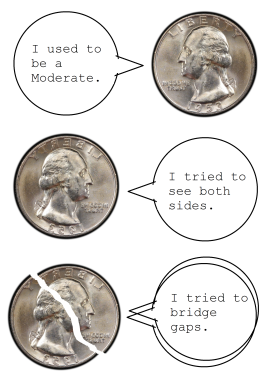

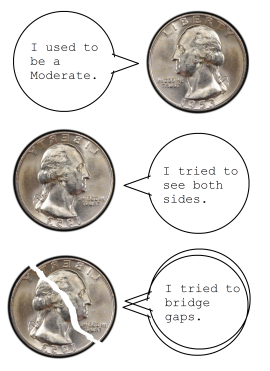

It wasn’t until I decided my cartoon character deserved an origin story that I began to fully understand that elderly couple’s prejudice against language. I started with this wordless sequence:

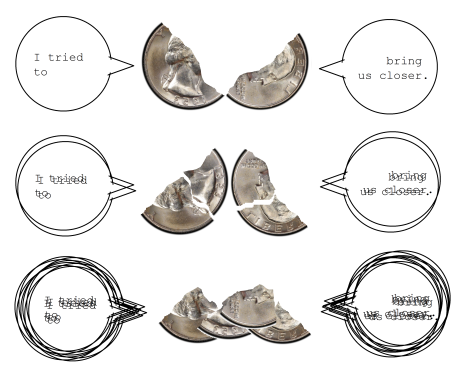

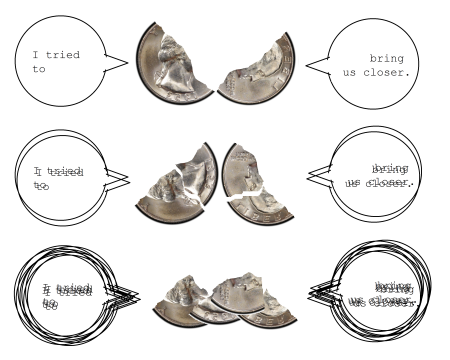

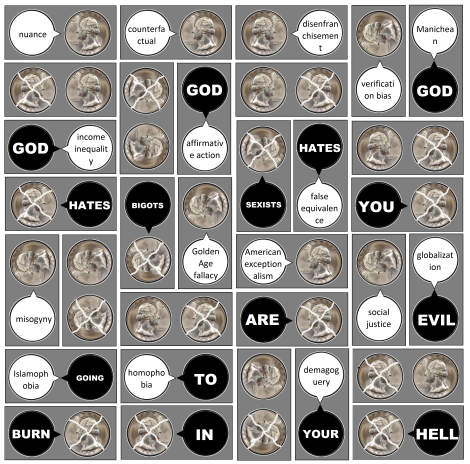

I liked it fine, but it felt incomplete. Maybe it deserved some dialogue, and so I added talk balloons, but without knowing exactly what I wanted George Washington to be saying. I just liked the talk balloons as visual elements offsetting the quarters. I even made them from the same image by whiting out their centers. But I still assumed I’d have to fill them in eventually. Stan Lee hired writers at Marvel in the 60s based on how well they filled in empty talk balloons from a Fantastic Four issue, so I started writing a script to do the same. I titled it “How the Radical Right Turned Me into the Radical Left.” It looked like this when I was done:

It’s probably revealing that I like the illegible words best. The phrases double then quadruple, turning into a visual representation of meaningless noise. Which is how I feel now about political statements that fall short of absolute condemnation of Donald Trump and anyone who voted for him. “It worked” is darkly ironic–I’ve become a mirror version of the kind of Tea Party extremist I hate–but that falls short for me. All I want to hear is the uncompromising blackness of that final talk bubble.

As I watched news agency after news agency call the election for Trump, words failed me then too. The wordless version is better. It’s not only its silent self, but it also contains the scripted version, plus a range of other unwritten but evocatively present versions too. No words somehow allow for all words.

Or should I set aside my anti-word extremism and try to compromise? Would a bipartisan combination of the two work best?

Like the GOP, the word-version controls almost the entire sequence, but no words get the all-important final word. Which is also the script I’m writing for America. My next cartoon is silent too. I’ve literally put myself inside that two-faced quarter, and I will stay there until Trump and all of his rock-throwing GOP punks are gone–via resignation, impeachment, or nuclear Armageddon, I really don’t care. If you would also like to make a Two-Faced version of yourself, I’ve included step-by-step instructions at the bottom of the page.

Step 1. Watch country elect pussy-grabbing bigot for president.

Step 2. Stop shaving.

Step 3. Shave right half of face.

Step 4. Take selfie.

Step 5. Shit around with selfie in Word Paint while country plummets into moral abyss.

Step 6. Vow vengeance in 2018.

November 21, 2016

How to Talk to the GOP

In 1996, Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich sent a memo to GOP candidates in response to their plea: “I wish I could speak like Newt.”

“That,” Newt humbly explained, “takes years of practice. But, we believe that you could have a significant impact on your campaign and the way you communicate if we help a little. That is why we have created … a directory of words to use in writing literature and mail, in preparing speeches, and in producing electronic media. The words and phrases are powerful. Read them. Memorize as many as possible. And remember that like any tool, these words will not help if they are not used.”

In the “Contrasting Words” section, he added: “Often we search hard for words to define our opponents. Sometimes we are hesitant to use contrast. Remember that creating a difference helps you. These are powerful words that can create a clear and easily understood contrast. Apply these to the opponent, their record, proposals and their party:

abuse of power

anti- (issue): flag, family, child, jobs

betray

bizarre

bosses

bureaucracy

cheat

coercion

“compassion” is not enough

collapse(ing)

consequences

corrupt

corruption

criminal rights

crisis

cynicism

decay

deeper

destroy

destructive

devour

disgrace

endanger

excuses

failure (fail)

greed

hypocrisy

ideological

impose

incompetent

insecure

insensitive

intolerant

liberal

lie

limit(s)

machine

mandate(s)

obsolete

pathetic

patronage

permissive attitude

pessimistic

punish (poor …)

radical

red tape

self-serving

selfish

sensationalists

shallow

shame

sick

spend(ing)

stagnation

status quo

steal

taxes

they/them

threaten

traitors

unionized

urgent (cy)

waste

welfare

Any of those words sound familiar? Gingrich, one of President-Elect Trump’s most vocal supporters during the campaign, is on the short-list for cabinet positions in the next administration–though not Communications Director. Apparently after twenty years of practice, no one in the GOP needs any training to “speak like Newt.”

Before the election, I had a vision of the U.S. coming together. I fantasized that Clinton would announce in her acceptance speech that she would fill half of her cabinet positions with Republicans and challenge Congress to send her only bills co-authored by Republicans and Democrats or face her veto. I was imagining a Democratic-controlled Senate too, but instead of shoving a leftwing Justice down the remaining throats of the GOP (as they so deeply deserved for refusing to vote on President Obama’s Supreme Court nominee last March), I wanted Clinton to renominate moderate Merrick Garland in a show of compromise and goodwill. I wanted this despite the fact that my personal political beliefs are over there with Bernie Sanders and the rest of those Socialist-hugging, LGBQT-loving, Wall-Street-regulating, Climate-Apocalypse-fighting do-gooders. I actually believed that being part of a democracy meant accepting and even celebrating that fact that I should only get what I want about half of the time. That even some of my cherished principles come second to the national need for our government to work from the center, to bridge extremes and find common ground. I was a Radical Moderate.

Until November 9th.

The problem with being a liberal is in the definition of the word. Politically it means “0pen to new behavior or opinions,” and educationally it means “concerned mainly with broadening a person’s general knowledge and experience.” The second refers to the Liberal Arts, the kind of college I teach in, though politically it amounts to same thing: broaden your understanding by being open to as many opinions as possible. Even and most especially your opponents’ opinions, since there’s nothing broadening about listening to ideas you already agree with.

Liberalism by definition is built on compromise and goodwill, which means not using “powerful words that can create a clear and easily understood contrast.” And that’s a pretty bad campaign strategy. You may notice that “compromise” and “goodwill” are not on Speaker Gingrich’s list. They’re not the kind of words that get angry villagers waving pitchforks as they march to the voting booth.

But Donald Trump took the Gingrich rhetoric primer even further. He wrote the playbook into a superhero comic book. I posted last summer how a dozen political commentators had likened Trump to a superhero, often to a certain other fascist-leaning billionaire. Jeet Heer wrote: “Trump is indeed a type of Batman: To his fans, he, like Bruce Wayne, is a brash, two-fisted billionaire playboy who uses his wealth to fight against a corrupt system.” Terry Brooks lampooned Trump’s speech at the Republican Convention: “He is your muscle and your voice in a dark, corrupt and malevolent world.” Trump even said it himself, telling a child lined up for a ride on his private helicopter at the Iowa State Fair:

“Yes, I am Batman.”

So that’s why I’ve invited guest blogger Harvey Dent to my site this week. Harvey, AKA “Two-Face,” was invented by Batman creators Bill Finger and Bob Kane back in 1942, and he’s been one of the Dark Knight’s baddest bad guys since.

Law-abiding District Attorney Dent became a supervillain after a thug threw acid in his face. Which is also how Donald Trump cured me of Moderatism. Though technically I don’t think Dent ought to be labeled a supervillain, since half of his actions should end up doing good. When faced with a tough choice, Two-Face flips a two-headed coin. I know that sounds like a rigged decision-making system (something the majority-losing President-Elect no longer talks about), but Two-Face carved a giant “X” through one of George Washington’s faces. Which is a perfect metaphor for the U.S. right now.

I’ve also asked Mr. Dent to serve as Communications Director to liberal candidates. Democrats need a strategy for talking to voters. Liberals, being liberal, have a tendency to express themselves in complicated terms–because how else can you think about complicated issues from multiple perspectives, all of which a good liberal wants to understand and bridge? But liberalism is the wrong langauge for communicating to someone who doesn’t already speak and think in it. Like Two-Face, Trump voters keep things simple. They believe in a static world of black and white, of absolute good and absolute evil. The last thing they care about is a gray world of ever-changing spectrums.

So I’ve asked Two-Face to speak from both sides of his head today. Candidates facing election in 2018 are welcome to select whichever set of words they think will be most effective for them.

And here’s a condensed version to print and keep in your wallet for quick reference. Be sure to hand out copies to family and friends:

Thanks, Harvey.

Oh, and by the way, which of George Washington’s heads came up today?

Yeah, I think we’ll be seeing a lot of that guy for the next four years.

…

[Gingrichspeak Update:

What Gingrich said on Twitter:

“The arrogance and hostility of the Hamilton cast to the Vice President elect ( a guest at the theater) is a reminder the left still fights.”

What Trump said on Twitter:

“Our wonderful future V.P. Mike Pence was harassed last night at the theater by the cast of Hamilton, cameras blazing.This should not happen!”

“The Theater must always be a safe and special place.The cast of Hamilton was very rude last night to a very good man, Mike Pence. Apologize!”

“The cast and producers of Hamilton, which I hear is highly overrated, should immediately apologize to Mike Pence for their terrible behavior“

What Hamilton actor Brandon Victor Dixon actually said at curtain call:

“We are the diverse America who are alarmed and anxious that your new administration will not protect us. We truly hope this show has inspired you to uphold our American values and work on behalf of all of us.”

Mr. Dixon, who plays Vice President Aaron Burr, apparently prefers the unscarred side of George Washington’s head: “hope,” “inspired,” “diverse,” “all of us”? Mr. Two-Face, could you please translate that into GOP for us?

Two-Face:

“We are the enraged American majority who are horrified and disgusted that your hate-mongering administration will persecute us and those we love. If you keep desecrating our American values and working for only the bigoted and the greedy, we will damn sure make you regret it.”

Which do you prefer?

November 14, 2016

Sexualizing Was Not Intended

“Demographics may also account for Marvel’s decision to withdraw a variant cover of the then-upcoming Invincible Iron Man #1 that featured a sexualized depiction of fifteen-year-old Riri Williams. After the comics site The Mary Sue criticized the image for promoting the attitude that the character was “not a true female superhero until you can imagine having sex with her,” Artist J. Scott Campbell responded on Twitter that “‘sexualizing’ was not intended,” though he added, “Is it THAT different?” The character’s crop top and low-cut leggings would be unremarkable by 90s standards. The issue was released November 9, the day after Hillary Clinton defeated Donald Trump to become the first female President of the United States.”

I wrote that paragraph a month ago, thinking it would appear next year in my book Superhero Comics. I went back to the manuscript on November 10 and deleted that last sentence. The chapter is about gender, how superhero comics have represented female characters for the last 75 years, and it had been nice to end the section on an upbeat note. Yes, comics have traditionally defined strong male heroes in relation to weak female victims and love interests, and, yes, comics have created strong female heroes through hypersexualized images that still paradoxically suggests the characters’ physical weakness, but those norms have begun to change, probably due to the rise in female readers and the larger cultural shift away from sexism.

I guess I should delete that last bit too: “cultural shift away from sexism”? Is that still a thing?

I’ve been putting the finishing touches on the book manuscript, and had recently added another paragraph to the gender chapter:

The 90s also coincides with Gail Simone’s identification of the “Women in Refrigerators” trope encapsulated in Green Lantern #54 (August 1994) in which the hero discovers his girlfriend’s corpse stuffed in a refrigerator by his arch enemy. In 1999 Simone published an online list of dozens of female characters who had been “killed, raped, depowered, crippled, turned evil, maimed, tortured, contracted a disease or had other life-derailing tragedies befall her.” Simone hypothesized that the “comics-buying public being mostly male” was a reason for the trend:

So, it’s possible that less thought might be given to the impact the death of a female character might have on the readership. Or, it’s possible that there’s rarely a fan outcry when a female is killed. Or, maybe since many major female characters were spin-offs of popular male heroes, it was felt that they had to go to keep the male heroes unique, and get rid of “baggage”. Or maybe many of the male creators simply relate less to female characters. Or maybe it’s a combination of these.

Whatever the reason, she asked:

if most major women characters are eventually cannon fodder of one type or another, how does that affect the female readers? … Combine this trend with the bad girl comics and you have a very weird, slightly hostile environment for women down at the friendly comics shoppe.

Many online responses to the list confirmed that hostility, but most comics creators responded sympathetically, including Ron Marz, who wrote the Green Lantern episode that inspired the list’s title:

Comics have a long history as a male-oriented and male-dominated industry. … I do think comics can and should be more sensitive to female characters. But these are times in which the general editorial mindset is “cut to the fight scene,” in which half-naked women on covers spike sales. Publishers are unfortunately more concerned with survival than with sensitivity to women. And that’s a shame. If we want to save our industry, maybe we should stop ignoring half the population as possible readers.

Dwayne McDuffie responded with that hope that “maybe more women will be inspired to take the reins and write some female characters who aren’t plot devices to complicate the hero’s life.” Simone would later write Wonder Woman and Birds of Prey, which featured Barbara Gordon, a character prominently featured on the WiR list.

See how naively upbeat I like to be? All it takes is one white women like Simone and one black man like McDuffie, and superhero comics are saved. Never mind the reactions I got when I posted about superhero gender norms at the very-weird-slightly-hostile-toward-women-environment of the friendly Reddit comicbooks subgroup. Here are some highlights:

“I see someone is finding out that sex sells. You act like this hasn’t been going on forever in every medium man has ever invented.”

“Power Girl isn’t even human so it doesn’t matter what she looks like.”

“men are hyper visualized as much as women if not more, and are probably more unnatural and unrealistic than women. While women in the comics don’t wear that much clothes, women in other competitive sports don’t wear that much either. While the big tits seems unrealistic, there are others who would beg to differ (Gina Carano for example, [the chick in deadpool])”

“Heterosexual males can’t ignore boobs. Just because you don’t like it doesn’t mean we start a campaign to stop it.”

And my cringingly least favorite:

“This shit gets me so hard.”

But, hey, it’s all just locker room talk, right? Hostile workplace environment? What’s that? When President Trump reduces or eliminates the Department of Education, all of those Title IX coordinators hired to comply with former President Obama’s anti-discrimination mandates will be fired, and we can go back to old school norms.

A poll by the Public Religion Research Institute found that 72% of Trump supporters feel that America has changed for the worst since the 1950s. Were things THAT different then? Well, in 1950, 34% of women worked outside the home. In 2002, 60% did. In 1977, 74% of men and 52% of women believed husbands should earn money and wives stay home. In 2008, only 40% of men and 37% of women held those minority views.

There was also only one female superhero in the 50s: Wonder Woman. Lynda Carter, who played her in the 70s, guest-starred last month on Supergirl. Instead of an Amazon of Paradise Island, Carter was the President of the United States. The show is goofy as hell, but I actually find it moving sometimes–the portrayal of so many strong women and, even better, how both other women and men look up to them as role models. One episode featured a twelve-year-old boy whose hero wasn’t Superman but Supergirl. We watch the show with our sixteen-year-old son, and I was proud that he was growing up in a world where that was normal. Why wouldn’t everyone look up to a woman as a leader?

But you know me. Naively upbeat. I guess I’ll delete that last assumption now too, since according to our next Reddit-minded President, a woman is not a true woman until you can imagine having sex with her. Or, as Trump explained to Fox News anchor Sean Hannity last March after the first round of groping allegations:

“I was so furious about that story, because there’s nobody that respects women more than I do, Sean, you know that. And I treat women with respect. And I have — we all have fun. We all have good times.”

It’s hard even for me to imagine that more women will be inspired to take the reins after last week. America has a long history as a male-oriented and male-dominated nation, and it looks like those fun and good times are back again. (Refrigerators sold separately.)

November 7, 2016

Medieval Comics?

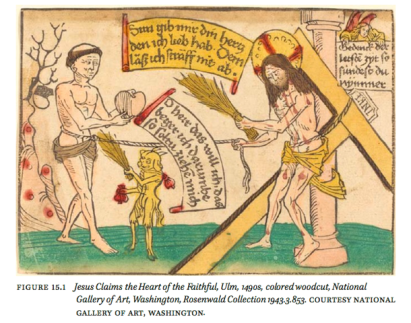

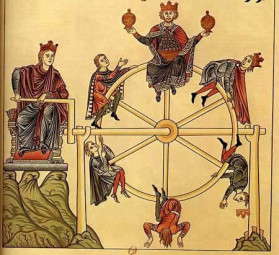

Is there such a thing? Some scholars object to the anachronistic use of the 20th-century term “comics” applied to anything that predates its etymology–especially when the predating is by centuries not decades. But I’m less sure. Look at this illustration from the 1490s.

The small angel in the upper right corner displays a scroll that reads:

“Gedenck der /lestē zÿt so / sündest du / nÿmmer”

[Think of the last days; then you will never sin]

Although it wouldn’t have been called a “caption box” in its day, I’m not sure how that word-filled square is any different from the caption boxes that appear in contemporary comics. Medieval scholars call the two other word-filled shapes “speech scrolls”:

“‘Sun gib mir din hercz /den ich lieb hab · Dem läß ich sträf nit ab ·’”

[“Son, give me your heart. I do not remit the punishment of the one that I hold dear”

“‘O herr das will ich · das / beger ich darumbe / so soltu ziehē mich’”

[“Oh Lord, this I want, I desire it, for this reason thus you pull me”]

There are no “pointers,” so the speakers are indicated by proximity and the curve of the scrolls toward each figure’s face. But that we can understand these words as a command and a response spoken by the two figures at the moment depicted means a “speech scroll” and a “speech balloon” differ in shape and not much else.

But comics, even contemporary comics, aren’t defined by speech balloons and caption boxes. Those, arguably, are just elements that can appear in a variety of images including a comic or a book illustration (whether 21st century of 15th) but don’t require the image to be classified as a “comic.” Though it produces problems for such apparent “comics” as Far Side and Family Circle, it’s a reasonable point. When we call something a comic book, we typically mean a visual story that’s divided into rows of panels across a page.

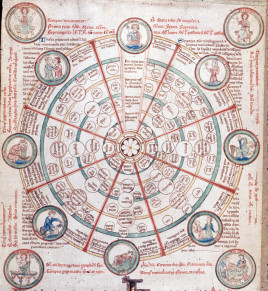

Maybe something like Valerius Maximus’ Memorabilia: intrigue and murder in Ancient Rome?

Chantry Westwell considers that 1470s piece a comic, writing about it and other “Medieval Comics” for the British Museum’s Medieval Manuscripts Blog in 2014. Steve Ditko favored the same three-row layout:

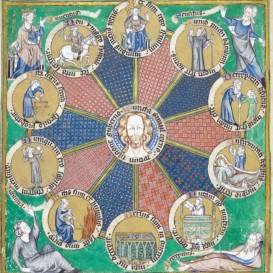

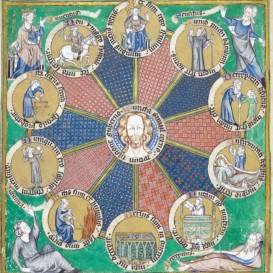

The top image was sent to me by graphic novelist Kevin Pyle after he and I met at a comics symposium in NYC last month. Martha Rust, an associate professor of English at New York University, was lecturing on the use of wheels and roundels in Medieval manuscripts. I was struck by how much the roundel functions like a panel in contemporary comics.

When discussing the early fourteenth-century Psalter of Robert de Lille, Rust notes that a “circle divided into wedges by means of its ‘spokes’ depicts a sequence”–a style still seen in some comic book page layouts:

The roundels also appear “to rest on the roll of parchment rather than to inhere in it and thus to have a notional manipulability–as if we could pick them up and move them around.”

While roundels make a “visual allusion to disks or coins,” many contemporary panels are more like irregular playing cards with their edges overlapping as so have that same “notional manipulability”:

And the occasional roundel still shows up too, though usually only one per page:

The Psalter of Robert de Lille’s wheel of fortune also captures how a comics reader views each panel one at a time while also being aware of the page layout at a whole. The image of God at the center declares: “I see all at once; I govern the whole by my plan.”

But whether you want to classify this and similar Medieval manuscripts as “comics” or simply “image-texts,” they are useful for revealing things about the current comics form because they are not constrained by the conventions that came to dominate the medium. For instance, this image from the twelfth-century illuminated encyclopedia Hortus delicarium (Garden of Delights) doesn’t rely on panels and gutters to tell its narrative:

Because, as Rust notes, the six figures represent “the same person at different points on Fortune’s wheel,” the illustration is equivalent to six panels that could (to worse effect) be drawn as six separately framed wheels with only one figure on each wheel at a time. More interestingly, Fortune, the figure turning the wheel, is present at each of the six moments in time–and yet she is a static image too. She’s both in time and out of time–an embodiment of the gutter.

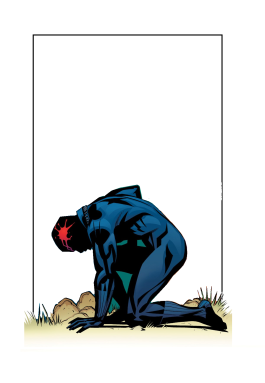

Her paradoxical relationship to the six turning figures is easy to see because the image doesn’t use panels to organize story time or page layout. But compare that to the first page of Ta-Nehisi Coates and Brian Stelfreeze’s 2016 Black Panther:

Like the Hortus delicarium illustration, this image represents multiple moments in time. And, like Fortune turning the wheel, Black Panther is present in all four scenes. Divided into conceptual units, the implied sequence looks like this:

And, because Black Panther is recalling these three memories as he crouches in a present moment:

This, frankly, is more than I would have expected from a writer approaching the comics form for the first time. But maybe that fresh eye helped Coates, with the aid of comics veteran Stelfreeze, get here. Like Medieval illustrators, they weren’t as bound by 20th-century comics conventions that make the panel the primary conceptual unit.

So while I’m happy to welcome the category of “Medieval Comics” to the multiverse, I’m even happier to view contemporary comics through its fresh eye.

October 31, 2016

Halloween Homage: Poe, the Grandfather of Superheroes

I taught a Satanist once. Nice kid, polite, well-spoken, adept with a monochromatic wardrobe. I was a new hire in a Virginia high school, so as far as I knew the whole building was slithering with demon-worshipping students and staff, but this kid (I’ve honestly forgotten his name) was the only one displaying The Satanic Bible on his desk. The weird thing was another kid (forgot his name too) sitting two seats down. The Bible on that desk was of the non-Satanic variety. Born Agains were common as Confederate flags (a group met every morning by the faculty parking lot to pray and smoke cigarettes), but this polite, well-spoken, fashion-neutral young man was joining the priesthood after graduation.

I figured God had been reading too many X-Men comics and wanted to see what a real-life Professor X vs. Magneto face-off looked like. He got His chance the morning of the first Poe assignment. I forget which title I’d typed on my English Honors syllabus, which body had been walled into which plot device, but discussion didn’t get far. The Satanist raised his hand first:

“This story portrays a man working to fulfill his highest human potential.”

The room was silent. The room was usually silent—it was first period—but normally all eyes didn’t swerve to stare at our future priest quite so intensely. He blinked, not certain he’d heard correctly, probably a mirror of my face. His arch-nemesis was ready to elucidate his opinion, but then God chickened out, booming His voice over the P.A. speaker. Actually it was the secretary’s voice, calling the Satanist down to the principal’s office. I literally never saw him again.

The priest went on to earn an A, and to write an end-of-year card thanking me, his agnostic teacher, for making room for Jesus Christ in his classroom (presumably because I’d allowed and even encouraged him to write all of his analytical essays on religious topics: Jesus and Hester, Jesus and Gatsby, Jesus and Lenny, etc.). I don’t think he believed me when I told him Poe was a Christian. I doubt the Satanist could have gotten his head around the ying and yang of that either. Poe, father of both detective fiction and science fiction, was a pro at combining opposing forces.

Scifi and detection may not patrol polar ends of the literary axis, but their rosters, unlike the X-Men’s and the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants’, don’t overlap. Detectives deal in crime, which means urban, which means right now. Expect grit in your blood puddles. Scifi is fantasy, is speculative, is otherworldly. Anything but the here and now. The tech is early Victorian, so you need a balloon to visit that city of telepaths on the moon. But Poe’s proto-Sherlock Dupin rarely leaves his Paris apartment, content to solve murders by combing clues from columns in The Daily Planet or its Parisian equivalents.

Of course the term “detective fiction” wasn’t coined till decades after Poe’s death, “science fiction” almost a century later, but like any good retcon, the memory of their non-existence has been lobotomized from the multiverse. Poe was a mostly monogamous author, so the mother of both his children was the Gothic. Scifi and DF, however, are promiscuous little brats, and so the family tree gets knotty before it sprouts capes and spandex. But let it be known: Poe is also the grandfather of the superhero.

If all genres are combinations of pre-existing elements, the superhero hails from an orgy. Scifi and DF hosted it at their private mad-house, Maison de Sante (later renamed Arkham Asylum). Guests arrived masked and scribbled “William Wilson” on their nametags. Except Hop-frog, a homicidal dwarf who burnt the building down, though not before the next generation of freaks was already gestating. There’s a reason Batman premiered in Detective Comics. Superheroes are fantastical detectives. They and/or their unearthly powers travel from far far away to fight crime in your urban backyard.

In addition to ballooning and ratiocinating, Poe’s superpowers included laying bricks, talking to mummies, pulling teeth, shadowing strangers, hunting pirate gold, blurting confessions, and hypnotizing corpses. He even pulled on a masque or two, but most of his guilt-hobbled monsters apprehend themselves. Dupin deduces a rare exception: the mother and daughter stuffed up a chimney in the Rue Morgue are the victims of (SPOILER ALERT!) an escaped orangutan. The revelation is as disappointing as it sounds, so you might want to skip ahead four and half decades; Arthur Conan Doyle’s knock-off detective is more beloved for a reason. Space tourism also spiked after Poe’s telescope hoax opened the first lunar Welcome Center. He even staffed it with actual batmen (“Vespertilio-homo”). Which is to say neither of his boys, Scifi or DF, were the sharpest quills in the proto-crayon box. They were just the first.

Poe never tried to browbeat them into the same story though, so no superpowered detectives for another century. No ultimate battles between Good and Evil either. God knows what Guidance was thinking when they scheduled a Satanist and an aspiring priest in my same English section. It was probably dumb luck, or the fated pull of opposites. I’m no Poe, but they might have made a dynamic duo with me as their mentoring mid-point. If only Hallmark made Lucifer-themed thank you cards.

Chris Gavaler's Blog

- Chris Gavaler's profile

- 3 followers