Grant McCracken's Blog, page 18

March 24, 2014

Pharrell, Happy and how to make contemporary culture

This video has been seen 145 million times on YouTube.

It’s not uncommon to use “real people” in videos. Sara Bareilles did it recently in Brave.

I don’t know about you, but often this exercise makes me uncomfortable. These days, I know I am supposed to distinguish piously between “real people” and “celebrities.” I know we believe “real people = authentic” and “celebrities = fake.”

I try, I really do. But finally I end up feeling that real people (i.e., you and me) are being patronized. Clearly, someone in the band stayed up too late talking about crowd-sourcing, fan bases, and the importance of fostering the people. So the next video just had to have real people in it.

But there are two problems. First, real people aren’t always very interesting. Second, they aren’t very real. The process of shooting video sometimes provokes what we might call the Karaoke effect. We are not recruiting real people for the video. We are recruiting people who have spend a lot of time pretending to be famous people. So what we really get for the video are people who have pretended to be celebrities now being asked to pretend to be real people.

A different proposition, surely. In our Karaoke culture, a camera is a dangerous ontological weapon. It transforms real people into fake celebrities. And we’re now trapped. We tire of celebrity culture and wish to escape it. But here at least we can’t. Everyone has felt the vampiric bite of fame. We may not be celebrities but we can’t ever go back to being “real.” (Whatever that was, and most anthropologist would insist that “real” is constructed just as much as “phony” is.)

[By the way, this is what it is to live in a media saturated society. A police detective told me once that he has a hard time interviewing suspects. They have seen so many Law and Order interrogations, they believe they know exactly how the interview is supposed to go and start answering questions he has not asked.]

BUT MY POINT IS SIMPLE (and I am sorry to have taken 7 paragraphs to get there): The Happy video from Pharrell does not make me feel this way. I like watching these people dance and sometimes sing. Evidently others do too. That’s the only way Happy could score 145 million views.

The question is why. What does Happy do differently? How do these “real people” differ from the real people who feature so prominently in music, marketing and advertising?

Part of the answer is that this video comes from started as a 24 Hour project. So the producers could choose the best frame out of every 360 frames, as it were. They had a lot to work with.

Second, most of the people in the Pharrell video are auditioned. So they are not that real after all. It looks like the video is an act of perfect spontaneity, that they just took the camera out into the streets of LA, but no. Some of these actors are so good, they accomplished sprezzatura: they concealed their art with art.

But there is some ineluctable mystery here. These performances are dazzling. It feels like these people “own” their performances. And it’s important for us to know why. Every cultural artifact has something to learn here. Pharrell and We Are From LA have solved an essential problem. It’s important to now how

Here are some of my favorite performances. I hope Pharrell and creators We Are From LA will forgive me this use of these materials. (Before they object, I would ask that they keep in mind that Nardwaur sent me.) Also, if the people pictured happen to see this post, I hope they get in touch so that I can name them.

Look for these designations: Eeriest imitation, best dancing, most beautiful woman, scariest handbag, etc. Slide 18 is for me the splendid moment. Two girls swaying in a car. Perfect.

I think why this video works so well is that it reverses the polarity of popular culture and the present craze for “real people.” Too often, the real people are forced-marched into the video, there to Karaoke as best they can. But in the Happy case, the song goes to them. These real people are not conscripted. The “press” runs the other way.

One measure of success: there are celebrities in this video (Jamie Foxx, Steve Carrell, Kelly Osbourne) but they do not matter to the video very much, and almost feel a little additional, as if horning in. As in, “who invited you?” Kelly Osbourne is perhaps the exception. I’ve always thought of her as someone who was merely famous for being famous, but with that weird “air square” she does something somehow sublime and redeems herself. Less a celebrity and now interesting. This video has something that is capable of rescuing celebrities from their celebrity. And that’s saying something.

There were ideas at work here. Here’s a passage from a wonderful piece in FastCo by Mary Kaye Shilling.

Those chosen by audition had the advantage of getting the song in advance, allowing them to rehearse their moves. But on the day itself, everyone got just one take, including Pharrell. “That’s what accounts for the charm,” says [iamOther VP Mimi] Valdes. “Everyone knew they had one shot–this was their moment to go all out, and we love that.”

“The video’s imperfections, the funny bloopers and mess-ups, are what give it character,” says Pharrell, whose own performances alternated between what he calls “semi-choreographed” (see the bowling alley at 11:00 p.m.) and improvisation. “I’m not interested in perfection. It’s boring. Some of my favorite moments are accidental.”

Lots of meaning makers in the present day continue to have what we might call a “sound stage” mentality. They manhandle reality for our larger cultural purposes. But I think this Happy video makes it clear that the more sensible, indeed, the necessary strategy is to let the brand out into the world, there to take on the content, color, and sheer propulsive force of what happens there.

Hat’s off to the following creatives:

Jett Steiger, Jon Beattie, Alexis Zabe, Mimi Valdez, Clement Durou, Pierre Dupaquier, Pharrell, WAFLA, Iconoclast, and iamOther

March 21, 2014

Brands Being Human

Subaru is doing great work for the SyFy’s Being Human. Here’s one example:

This is an insider ad. You have to know the show to get what’s happening. These are werewolves. They’ve gone into the woods to “turn.” The brand has found the spirit of the show and “had a little fun with it.” Romantic feeling is imposed on something that will shortly turn nasty and violent. Clever. And this is absolutely in the spirit of Being Human which plays with genre expectation constantly and well.

Here is Being Human in action. In this scene, Sally, the ghost, discovers that her house is up for sale and she decides to discourage home buyers with a ghostly trick. Ooooooooooo! In this scene, remember, she is invisible.

Generally speaking, Subaru has done a great job claiming a nest of companionable, cozy, domestic meanings for the brand. It has attached itself to “family” as well as any brand in the biz. (And that’s saying something, considering that so many brands are trying to make this connection.) Recall the Subaru ads that feature dogs aging and kids practicing for their driver’s license. This is great work but it may leave the Subaru brand defined as something perhaps a little too domestic and of-this-world.

The Being Human work manages this problem beautifully. A brand that verges on the humble and everyday becomes suddenly exotic and even daring. The Subaru meanings expand wonderfully.

Notice how elegantly this is accomplished. The Being Human work is site-specific and exists, in effect, only for the Being Human audience. There is no danger that the broader Subaru market will see this work and no danger that it will transform their “cosy” associations with the brand. This is brand surgery.

Another thing I like about this approach is that it is the opposite of product placement. Instead of jamming the product into the show, the show is allowed to find its way into the “brandscape,” to use John Sherry’s term. And both the show and the brand profit.

Product placement is often an absolute tax on a show. You know that moment when the appearance of the product suspends your suspension of disbelief. You might as well stop watching and thousands no doubt do. I don’t care how much the show makes from product placement. In many cases, the artistic price is too high. Plus, as a strategy, this is just plain dumb. It says in effect, “People aren’t watching our ads! Ok, so let’s force them to look at the product! We’ll make them watch us!” You’ll make them watch you? This is your idea of persuasion. This is your idea of managing meanings? Really?

There’s another Subaru ad for Being Human that feels, to me, less successful. It shows three actors acting like characters from the show. See it here:

This execution feels wrong to me and it serves I think as a useful test of where this strategy can work and where it fails. When the ad is merely leveraging the creative original, it feels like a pale imitation and it provokes, I think, a relative loss of value. By which I mean, more is taken from the show than is returned to it. The brand is merely exploiting the dramatic riches of Being Human and not taking possession of them for larger creative play. In the immortal words of T.S. Eliot, “bad poets borrow, good poets steal.” This spot borrows where the first one steals. This is not as bad as product placement but it isn’t a lot better.

Carmichael Lynch, the agency in question, has done great things for Subaru. There is a cultural sensitivity at work here that really is exceptional. And our opening “werewolf” ad breaks new ground. Letting the brand out to play in an ad, in this way, is to let the brand out to play in the world. And this is one of those cases, where brand and ad are working together, borrowing meanings from one another, to their mutual benefit. Both brand and show get bigger, richer, and more interesting.

But what might be more remarkable is the fact that the Carmichael Lynch work takes Subaru almost no other automotive brand is prepared to go. This is daring. It is clever. It participates in popular culture. It makes the brand a living, breathing presence in the life of the consumer and our culture. It takes the brand a little closer to being human.

Acknowledgments

Dean Evans, CMO, Subaru

I am hoping Carmichael Lynch will send me names of the creative team so that I can give them a mention for this really exemplary work. Watch this space.

March 20, 2014

miraculous ascensions

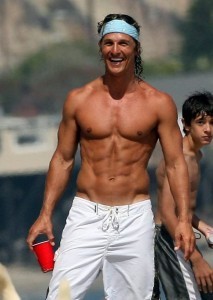

What are the odds that this actor:

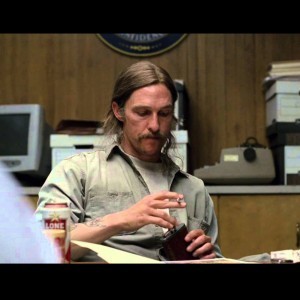

would become this actor:

And this actor, once a good time Charlie of the first order:

would become this actor:

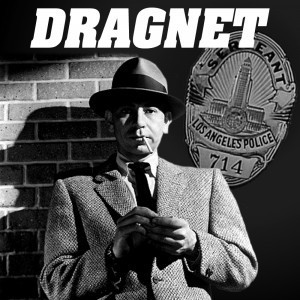

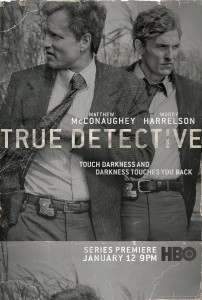

And, that, in the larger scheme of things, this show

would become this show:

It’s almost as if pop culture is becoming culture.

March 19, 2014

Abercrombie and Fitch needs a Somali intervention (oh, and a CCO)

Mike Jeffries, CEO of Abercrombie and Fitch, can expect a C-suite invasion any day now. Some guy is going to come climbing over the side and say, “Look at me. Look at me. I’m the captain now.”

Mike Jeffries, CEO of Abercrombie and Fitch, can expect a C-suite invasion any day now. Some guy is going to come climbing over the side and say, “Look at me. Look at me. I’m the captain now.”

The problem is simple. Somehow A&F drifted out shipping lanes. It lost it’s navigational signals. Sales fell. Wall Street got like so mad.

This is odd because Jeffries was once indisputably a captain, not just of A&F, but retail writ large. He seemed to know exactly what consumers wanted. As Matthew Shaer puts it in a recent New York Magazine,

“From 1992, when [Jeffries] was hired at Abercrombie, to the early aughts, Jeffries presided over one of the more impressive runs in the history of modern American retail. And he did it by turning an all-but-moribund clothing brand, best known as a fusty safari outfitter, into a multibillion-dollar behemoth with more than a thousand storefronts and a style that competitors were tripping over one another to imitate. Unlike his peers, who tended to view the youth market with clinical detachment, Jeffries had a Peter Pan–like ability to commune with the whims of the average American teen.”

(Mr. Shaer’s excellent essay can be found here.)

But time and teens move on. And Jeffries somehow lost touch.

A company designer gives us a glimpse why. She told Shaer: “[Jeffries] has a tough time moving past that classic American aesthetic of jeans and polo shirts”

Retail analyst Wendy Liebmann has something like the same story to tell. She told Shaer: “The sexy collegiate image fit into the age of Gossip Girl and 90210 but now it feels like it’s grounded in an era that’s at least ten years old. I don’t think shoppers in the U.S. and Canada have totally walked away. But, as a whole, I think shoppers have moved on.”

Erik Gordon at the University of Michigan’s business school has studied Jeffries. “If our hero has a fatal flaw, it’s that the world changed and he hasn’t.”

It’s a pretty standard problem. Along comes a guy like Jeffries who seems to have a perfect sense of what the consumer wants. What he does not see is that this is an illusion. What he knows is merely what he wants. This just happens to be what the consumer wants…for the moment. Eventually taste and preference will change. And when that happens, there is a sudden, cataclysmic loss of consumer interest and investor confidence.

It’s hard to feel sorry for Jeffries. All he had to do was drive through Brooklyn to notice that the preppie look was losing share and that in fact most people preferred to look like survivors of the American civil war. (You know, I’m just an anthropologist, but I feel confident that “preppie” and “civil war” are quite different looks.)

And this is why you hire a Chief Culture Officer, someone who spends his or her life listening to culture, monitoring consumer taste and preferences, watching for trends and, when necessary, yelling, “OMG. Something is happening out there.” The CEO can still “go with his/her gut” but now he/she has someone standing by to report on disruptions. And save you from your illusions.

Everyone likes to think they have perfect pitch when it comes to retail. And when you have a run as long as the one Jeffries has had, you are entitled to a sense of your own infallibility. But we have to know that reading a world that thrashes with change is fantastically difficult. And no one can be right all the time.

Or think of this way. It has to be better to share a little power now (with your new Chief Culture Officer) than have to give it all away when someone climbs aboard up and says, “Look at me. Look at me. I’m the captain now.”

For my book Chief Culture Officer, please go here.

March 14, 2014

Are photos a secret ingredient of the internet economy?

I’ve been asking myself the big question: “Why did FB buy What’sApp for $19 billion?”

I’ve been asking myself the big question: “Why did FB buy What’sApp for $19 billion?”

I know I am late to the party. But surely this puzzle is still a puzzle even if the buzz(le) has moved on.

For me, there are four answers.

1) Facebook was trying to stay in touch with its early adopters, specifically young people who are now migrating away from Facebook at speed. Early adopters are early warning. Where they go, the world will follow.

2) Facebook was attempting to disrupt a disrupter. Mark Zuckerberg has read his Clay Christensen. He doesn’t want to suffer the fate of Friendster. WhatsApp looked like the future. So he bought it.

3) The third answer has to do with the power of photos. Whatsapp users send 600 million photos every day. (http://news.yahoo.com/whatsapp-19-billion-bet-facebook-053029423–finance.html) And Facebook knows what this means. Chris Hughes, a FB founder, thought that photos could make FB “sticky” and discovered that they made it positively magnetic. (Photos may be the biggest reason Facebook didn’t drop from view like Friendster.)

4) The fourth answer turns on the mysterious properties of the photograph. (This is a topic dear to my heart. I did research for Kodak in the US, Europe and Asia.)

We tend to think that photos matter because they are a record of the world. But this is only the necessary condition of their significance. The reason they really matter is that they are the single, smallest, richest, cheapest, easiest token of value and meaning online. We mint them. We trade them. We accumulate them. We treasure them.

Individually, photos are content coursing through our personal “economies.” They are the single most efficient way to build and sustain our social networks. We gift people with photos. They reciprocate. Hey, presto, a social world emerges.

Collectively, photos create a currency exchange. They are a secret machine for seeing, sharing, stapling, opening, sustaining and making relationships. Want to know where networks are going? See who is giving what to whom, in the photo department. Photos are in constant flight. They are a kind of complex adaptive system out of which some of our social order comes.

Why did Zuckerberg pay $19 billion for Whatsapp? He was following the photos, that secret ingredient of the internet economy.

March 4, 2014

Provocative Cadillac: rescuing the brand from bland (my latest at HBR)

Cadillac’s new spot Poolside is exploding. It shows a guy walking through his beautiful home musing on American virtues, values, and accomplishments. It debuted during the Superbowl and played again Sunday night during the Oscars.

Cadillac’s new spot Poolside is exploding. It shows a guy walking through his beautiful home musing on American virtues, values, and accomplishments. It debuted during the Superbowl and played again Sunday night during the Oscars.

Naturally, the world went ballistic. These days, in our ideologically conflicted moment, we can’t say anything about the American experiment with provoking supporters, denigrators, and a great storm of controversy.

Poolside is a celebration of hard work, risk taking, and American exceptionalism. For good measure, it goes after the French, those lazy so-and-sos who linger in cafés and take August off. Our hero (played by Neal McDonough) scorns these continental layabouts and counts up American accomplishments, including the trip to the moon. “Got a car up there. And we left the keys in it. You know why? Because we’re the only ones going back.”

Some said, “Bravo! Finally someone prepared to give voice to the things that made this country great.” Others said that this ad is an evocation of the ugly American, materialist America, and the dreadful 1%.

The marketing question is simple. Why is this ad going where angels fear to tread? Surely Cadillac and Rogue, the agency, knew that they were going to stir things up, that Poolside was going to go all cannon ball.

For the rest of the post, please go here to the Harvard Business Review Blog where it originally appeared.

My salute to the creatives didn’t make it into the HBR post. I note them here.

Marketing Team at Cadillac:

Craig Bierley, advertising director

Uwe Ellinghaus, CMO, Global Cadillac

Alan Batey, GM Vice President, U.S.

Creative team at Rogue:

Director Brennan Stasiewicz

Chief Creative Officer Lance Jensen

Executive Creative Director David Banta

Group CD / Art Director Kevin Daley

Copywriter Lance Jensen

Copywriter David Banta

Producer George Meeker

Executive Producer Jeff Miller

Agency Producer Paul Shannon

February 28, 2014

Minerva owls (now “winging” their way to winners)

January 31, 2014

Killer Women, killer critics

I am a fan of Tim Goodman’s work at The Hollywood Reporter.

I am a fan of Tim Goodman’s work at The Hollywood Reporter.

I read with pleasure his review of Killer Women.

It begins, “The ABC drama is killer bad. No, really, it’s shoot-me-now bad. ”

Oh, delicious, I thought. There are few things as nothing quite so satisfying as seeing justice done, especially when the culprit is a cynically bad piece of contemporary culture.

Go, Tim, go.

“It’s also one of those shows where, less than five minutes into it, you wonder what the actors were thinking when they signed on and then, immediately after that (perhaps a millisecond), you wonder if they’ve since fired their managers.”

But there’s a problem here. And that’s that Killer Woman is actually pretty good. Not perfect. Not in the class of the very good work of which TV is now capable. But it is well crafted, interesting, and likable.

Which raises a question: What was Tim Goodman doing?

I leave it to you, reader, to have a look at the show and the review, and see if you find a discrepancy. I think you’ll find one.

The second question: how big is the discrepancy?

If it’s a small discrepancy, we can put this down to pilot error. Even a great critic can have a bad day.

But if the discrepancy is big, more questions arise.

The third question: is this an act of hostility? Did Goodman seek deliberately to inflict harm on the show?

The fourth question: is this an abuse of power?

The fifth question: should THR take a sober look at the review and ask some tough questions? Was this an act of abuse? Is there, in Goodman’s work, a pattern of abuse?

The sixth question: are there grounds for a class action suit?

The costs of a hostile critic are astronomically high. Careers are diminished, sometimes ruined. Investments are lost. Enterprises (networks, production companies for instance) may founder. Value of the tangible and intangible kind disappears from the world. If the critic who causes this loss is acting from genuine motives and the honorable practice of his or her profession, well, some harm but no foul. But if the critic is deliberately inflicting harm, this will not do.

I understand that the come-back here is that reviews are so relative and personal that they cannot be objectively assessed. There is, in short, no way to criticize the critic. This may be true some of the time, but there are cases when the review and the reviewed are unmistakably discrepant. In this case, we can criticize the critic and in this case I think we must.

Minerva winner (4)

This is the last of Minerva winner. (But not the least. Order is no measure of merit.)

Thanks again to everyone who participated in the contest.

Congratulations, Chase Javier Goitia for a great piece of work.

[And an apology. Stripping out your name to send your essay to the judges, I also managed to strip out the title you had given your essay. Please could you remind me what it was. Apologies.]

[Title to follow]

Though both Kim Kardashian and Lena Dunham arise from the same culture at large, that is to say an affluent slice of society in the United States, they represent markedly differing cohorts who exist as foils in the same space.

Kardashian is a figurehead of the old Hollywood society scene carried to exhaustion, where her public persona is a carefully orchestrated facade of public appearances, tabloid stunts, and fashion braggadocio. We understand innately that there exists a separation between who she may be as a human being and the way she presents herself to us, in fact we know that any information about her personal life is either scandalously leaked or is groomed by PR, ergo no information is trustworthy.

Dunham, by contrast, represents the derivative of that cultural paradigm, deconstructing it in her professional works as well as her public persona, which is approachable and casual even though it would be naive to assume that such a tone lacks intent. Her show “Girls” exists as a bricolage of Gen Y culture; raised on the Internet, wary of popularity, and dismissive of Hollywood’s stunts. Casting a critical eye but simultaneously enjoying mainstream events ‘ironically,’ her works elucidate the struggle of millennials to find authenticity in their lives and find their place in a world created by and for prior generations.

Kardashian is a point of crossover as her fame rests on her symbolic existence rather than on works of intrinsic merit, but her relationship with self-proclaimed genius and hipster hero Kanye West raises questions: Is there substance to Kim Kardashian that the paparazzi and reality TV cameras won’t show? If Yeezy is such a genius, how is he so easily seduced by her T&A and diva lifestyle?

Kim Kardashian’s sex tape is one in a long tradition of young women ravenous for fame, initially considered a scandal and then spun to her advantage as it helped establish her as a contemporary sex symbol. But if a Lena Dunham sex tape were leaked, would anyone care? “Girls” and “Tiny Furniture” feature such unabashed nudity by the characters she plays that there might be no scandal— her position as a feminist spokesperson allows her to admit that she enjoys sex and isn’t ashamed of her body. Young women may covet Kim’s curves but it’s Lena’s confidence and positivity that allows many twenty-somethings to identify with her; Lena’s stardom could appear reluctant if not for the fact that she helped create the environment she now enjoys.

The facade Dunham has crafted brings viewers into a purportedly private world where her insecurities and flaws are evident, where her femaleness isn’t tied to her desirability by men or her privilege, but it is her privilege, namely her family background, that has afforded her this opportunity. Dunham’s first work “Tiny Furniture” was made for less than 50k in her parents’ NYC flat, starring a cast of her friends. Nevertheless, the fact that she was able to produce a slice of her inner thoughts, and in so doing contribute a previously-absent voice to a generation, is a victory.

Kardashian flaunts her privilege loudly in the form of her beauty and wealth every time she appears on a red carpet in an outfit whose value approaches that of Brooklyn real estate, and Dunham flaunts hers subtly in candid Instagrams with comedy luminaries and young New York elite, but both manage to conceal their real selves from the public. Kim’s fame is escapist while Lena’s is populist. Both women appear to enjoy their lives and allow us to bask in the reflected glow.

The further thoughts here are that while both Kim and Lena are obviously considering the way they appear to the public, and doing so in different ways, who holds the stronger position? Because Lena uses the way she presents herself in public to analyze and dissect her insecurities, versus Kim’s plasticized version of her real self, is her glasnost actually a shrewd diversion? We know Kim has had plastic surgery and public meltdowns and is vain because that’s who she needs to be, but Lena doesn’t; she can make an introspective, self-critical show like Girls and use it for her own benefit (both as a platform and as working therapy), and isn’t that less secure, paradoxically?

What we can be certain of: both Dunham and Kardashian are public figures whose clever management of their self-presentation allow each to remain obscured from our scrutiny, but who each serve as a totem of a particular sort of fan. It is the archetypal complement between the extraverted, glam-obsessed that identifies with Kim, and the neurotic, earnest-to-a-fault that champions Lena. Our culture needs both because both those archetypes are in everyone, in varying proportions.

Which is to say: we created those goddesses in our own image.

January 30, 2014

Minerva winner (3)

This is winner 3 of the Minerva contest.

This is winner 3 of the Minerva contest.

Congratulations, Mariu Rodriquez

The What, How and Why Behind Kim and Lena.

Mariu Rodriquez

As I grabbed my binder full of random article about the different trends, artifacts and currencies of our culture, or at least the microcosm that I am part of – one filled by people’s magazine subscribers, WSJ’s marketplace readers, movie theater frequenters, and Rottentomatoes.com customer base – I thought to myself: I got this, I know her story, I watch her show and I’m fairly perceptive. Little did I know the place where both of them where about to take me.

Let’s start with the most striking differences. Kim; girly, curvy, sexy and glittery, resembles the classic full glam Hollywood style when women lived their everyday in perfect makeup. Lena, ladylike as well, presents herself in a colorful and quirky Brooklyn style.

Kim’s tone of voice is soft, she is poised, doesn’t swear much and is neutral and almost laconic about many things, from voting (her first-time vote was in Obama’s initial run) to even her haters’ nastiest comments. On the contrary, Lena is completely outspoken, spontaneous and opinionated. She speaks her mind out in an “I’ve always found paella kind of pretentious…” kind of way.

In terms of social class, it seems fair to say that Kim belongs to a “lower-upper” segment, often characterized by the need to get attention and “guard” their status through material possessions. Lena belongs to an artistic elite, both her parents are artists, a couple of her writings have appeared in the sophisticated and notable “The New Yorker,” and she even appeared in the “super snob” Vogue magazine at eleven, as part of a reportage about fashionista teens.

Another radical difference between the two is their stand on feminism. Lena is an openly feminist and Kim approved the idea of posing for Playboy because “sex is powerful and I think it’s empowering.” (Brockes, 2012)

Lastly, Kim could teach us all a master class on branding; every aspect of her persona – including her businesses – is consistent with her value proposition: “the full glam experience.” Dash – her store – does not have many items, but it is strategically stocked with products that attract girly teens that collect bottled water with the sister’s pictures in them. This is by no means a marketing trick because Kim is herself the personification of the full glam experience.

In terms of branding, Lena is not there yet. Even though her show, writings, movies and even twitter account share the same honesty and soul search, I do not think she is purposely committed to make her offering a revenue generating machine.

Loaded with differences, I am now ready to pass the torch to my deeper observer and unifier. From a personal standpoint, Kim and Lena are both relatable. Yes, Kim is financially well off and her lifestyle is completely aspirational to most of us, yet the dynamics inside her family, the sometimes rivalry and more often alliances, respect and closeness between each member are aspects one can relate to, either by experience or by wishful thinking.

Her type of show, classified by Susan Murray as a “docusoap,” is scripted and filled with artificial locations but it gives us access to real people, a family that is genuinely close and whose members at some point get tired of posing. This makes Kim as a brand, human and approachable.

(Murray & Oulette, 2009)

At the same time, Lena represents that stage in life when we need to find who we are at our very core and need our friends to share the journey with us. Be it to end a relationship, to find a job or just to go down the spiral of self-discovery, this is a stage we all can relate to as well. Aware or not, we all want to be as true to ourselves as possible.

From a sociological standpoint, they both serve as social factors in the socialization process of millennials. According to Durkheim, “individuals internalize cultural models of society and after assimilating these rules, they convert them into their own personal rules of conduct and behavior in life”. In this sense, Lena and Kim are opening the path of authenticity and family closeness for millenials to follow, and in a broader sense, are helping society rethink these values. (Farzaneh, 2013)

Perhaps in the future, we might see more closely tied families, nurtured by authentic relationships, which main challenge would be finding a technological bridge between generations.

They are also modeling our vision of entrepreneurship. Murray said that a reality star is an entrepreneur trying to establish a brand. However, I would argue that only when these stars have enough reach to impact a portion of their audience’s behavior and when its proposal is innovative enough is when they jump from being an independent business owner to being an entrepreneur.

Some wonder what is Kim’s innovation? It is definitively not a product or service, but rather an ability to cut through the judgmental clutter of being famous for nothing and build her persona around the fulfillment of accumulating experiences in life. Her show, her marriages, her brands, her latest Christmas Card photo shoot are not mere eccentricities but an urge to cease every opportunity that enriches life, her proposal is about accumulating interesting experience.

Perhaps this value proposition is made out of thin air, but it is a successful representation of what many millennials stand for today, especially when the Great Recession of 2008 made them rethink about what’s important in life.

Finally, let’s revisit the infamous narcissism of millenials. In a recent article, Emily Asfahani and Jennifer Aaker pointed out how new data is shifting this perception and showing instead that “millenials appear to be more interested in living lives defined by meaning than …happiness.” (Emily Esfahani Smith and Jennifer L. Aaker, 2013)

Meaning is about having a purpose, value, impact and connecting to a higher purpose, others, even the world. The key though is that “there are many sources of meaning…that we all experience day to day, moment to moment, in the form of these connections.” (Emily Esfahani Smith and Jennifer L. Aaker, 2013)

So yes, Kim and Lena are big time narcissists, but don’t we all need to see the light in ourselves in order to connect to the light in others, thus create meaning?

References:

1. Emma Brockes. Kim Kardashian: my life as a brand. The Guardian, Friday 7, September 2012.

2. Susan Murray and Laurie Oulette. Reality TV: Remaking Television Culture. New York University Press, 2009. Pp 67

3. Arash Farzaneh. http://suite101.com/a/the-influence-o...

4. http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/03/fas...

5. http://nymag.com/arts/tv/features/gir...

6. Emily Esfahani Smith and Jennifer L. Aaker. Millenial Searchers. The New York Times, Sunday 1, December 2013.