Grant McCracken's Blog, page 17

April 3, 2014

Innovation Exhaustion and the adaptive manager

The last few years, management thinking has been dominated by a big idea: innovation. And by this time a certain fatigue is setting in. Call it innovation exhaustion.

The last few years, management thinking has been dominated by a big idea: innovation. And by this time a certain fatigue is setting in. Call it innovation exhaustion.

Innovation is much harder than it looks. And even when we get it right, it proves not to answer all or the biggest of our problems.

The biggest of our problems is not that we need to take a constant flow of innovations to market to win share and fight the competition. Though, of course, we do. The biggest problem is that in the meantime we must live in a world that bucks and weaves with disruption, surprise, and confusion.

In fact, we can innovate constantly and well, and still find our organization at sea.

I think innovation arrested our attention because it looks like a good way to make ourselves responsive to a dynamic, increasingly unpredictable world. It was all part of that management philosophy that said is that the best way to manage the future was to invent it.

Recently, I’ve started to wonder whether the proper object for our attention should be adaptation. This is the study of adjustment that interacts constantly with strategy.

Innovation is hard. But adaptation is in us. It is perhaps our great and defining gift.

Rick Potts is director of the Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program and curator of anthropology at the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. He argues that adaptability is the secret to our success.

“[W]e started out as a small, apelike, herbivorous species 6 million years ago in tropical Africa, and after a history of origin and extinction of species, what’s left today is us: a single species all over the planet with an astonishing array of abilities to adjust.”

This feels like an old story but in fact it resists conventional wisdom. We are inclined to tell our story as if we (and it) were inevitable. It’s a kind of presentism, as if nature conspired to produce us, and that this evolutionary development could not have been otherwise.

But Potts points out that there was nothing inevitable about our rise. There were several hominid trials underway. Our numbers were tiny, competitors were formdidable, and the environment changed radically. Homo Sapiens was always an endangered species.

Why did we survive and thrive against the odds? Why us and not someone else? It is, Potts says, due to our gift, our particular genius, for adaptation.

“My view is that great variability in our ancestral environment was the big challenge of human evolution. The key was the ability to respond to those changes. We are probably the most adaptable mammal that has ever evolved on earth.”

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jill Neimark for the article in Discover Magazine. Find it here. And to Stephen Voss for the magnificent image.

April 2, 2014

Culture Camp London 2014

I am doing a Culture Camp in London June 13. Here’s the description. Please join us!

Course Description

This culture camp is designed to do two things:

1) expand your knowledge of the big changes transforming culture.

2) develop your ability to put this knowledge into action.

Culture is at the core of the creative’s professional competence. It is the well from which inspirations and innovations spring. It’s one reason startups and corporations need the cultural creative. This culture camp is designed to enhance your personal creativity and professional practice.

1. Knowledge of culture

We will look at 10 events shaping culture.

Half are structural changes.

1.1 The end of status as the great motive of mainstream culture.

1.2 The end of cool as the great driver of alternative culture.

1.3 The movement between dispersive cultures and convergent cultures.

1.4 The movement between fast cultures and slow cultures.

1.5 The shift from a “no knowledge” culture to a “new knowledge” culture.

Half are trends:

1.6 transformations in the domestic world (aka homeyness to great rooms)

1.7 transformations in the scale and logic of consumer expectation (from the industrial to the artisanal)

1.8 shifts from old networks to new networks (especially for Millennials)

1.9 shifts from single selves to multiple selves (especially for Millennials)

1.10 [this one is ‘top secret’ and will be revealed on the day]

2. Using our knowledge of culture

2.1 how to discover culture (using ethnography)

2.2 how to track and analyze culture (using anthropology)

2.3 how to hack culture (making memes)

2.4 how to build a brand

2.5 how to make ourselves indispensable to the corporation

Culture Camp is being sponsored by Design Management Institute and coincides with their London meetings. It is also being sponsored by Truth. (Special thanks to Leanne Tomasevic.)

The image is from Yanko Tsvetkov’s Atlas of Prejudice 2. I am keen to stage the culture camp in Tomato Europe, Wine and Vodka Europe, Olive Oil Europe, and of course Coffee Europe. Please let me know if you are interested in participating or sponsoring.

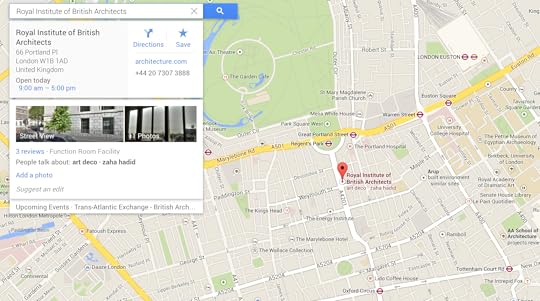

Culture Camp will be held 9:00 to 5:00 on June 13 at the Royal Institute of British Architects, 66 Portland Place, as below. (Register for the Culture Camp here. You don’t have to be a DMI or RIBA member to do so.

April 1, 2014

Hacking culture (an April Fool’s edition)

Ads like this are springing up in Toronto as people contemplate the prospect of another term for Mayor Rob Ford.

Ads like this are springing up in Toronto as people contemplate the prospect of another term for Mayor Rob Ford.

Ridicule is the order of the day. A decade ago, this would have taken place in Toronto bars and pubs. (In this once Scottish Presbyterian outpost, spirits and mockery used to meet every day after work.) But, hey presto, nowadays people can do a pretty good replica of the campaign sign.

What changed? Well, everything, mostly. The technology is there. Anyone can find a printer willing to bang out campaign signs. But the important change was the willingness to ape the experts and make culture for ourselves. People were once cowed. Making a campaign sign, not just for politicians anymore.

When culture was official, we didn’t dare presume. We didn’t dare make it or fake it or board it or hijack it, borrow it or make off with it, or “have a little fun with it.” We didn’t dare hack it. Now we do.

Phil Jones inserted himself in someone else’s real estate ads.

Goofy realtor smile. Matching shirt and tie. Bad mustache. Ill fitting wig, and all. Phil missed nothing.

People have made their own memorials on Brooklyn Bridge.

D-I-Y memorials. Hacking public space for private purposes? That’s something.

UNICEF hacked the vending machine

A Harvard student hacked the tour of the Yale campus.

Andre Levy, a Brazilian living in Germany, managed to hack the coin of the realm. His art now goes everywhere.

See more of Andre’s work at talesyoulose.tumblr.com.

The hacking thing begins, for near-history purposes, with the advent of Punk. Irreverent fans watched a band on stage and said, “Oh, I could do that, only like, way, way worse!”

And remember that jewel of the digital world in the 1990s when everyone was wowed by All Your Base Are Belong To Us? I remember several people saying, “Oh God, anyone can make an ad!”

That’s another difference. Our standards have gone up. We can all dispatch a campaign sign, a painted coin, even a rehabilitated vending machine. This used to be the kind of thing that only MIT engineering students could pull off. Prankster acumen, even this is being democratized.

The spirit of hacking is everywhere. It manifests itself even in your niece who bangs out NCIS fan fic effortlessly and with no sense that she is trespassing on anyone’s creative patch. Every consumer is now a producer, or near enough.

Everyone is in possession of the skill and the gumption to hack culture. It’s just a question of imagination. More and more, the public world looks like an opportunity for intervention. And for the rest of us, everyday will call for the wariness we exercise on April Fool’s Day. Could this be what it seems? Or is my culture being hacked.

Post script

Thanks to Leora Kornfeld for letting me know about Toronto campaign signs.

Speaking of hacking Toronto politics, there is a great experiment taking place on Twitter. It’s the work of someone (I will name him if he lets me) who has taken the name of Bert Xanadu and the persona of the Mayor of Toronto circa 1973. Follow him as @moviemayor. It’s like Groucho got a Twitter account.

For more on hacking culture, see my book Culturematic.

March 31, 2014

My London talk in June

In June, I am

In June, I amgiving a keynote in London for the Design Management Institute.

Here’s the title and the abstract.

Title:

A revolution in the works

how design leaders can master the coming cultural disruption

Abstract:

Some 40 years ago, Robert Venturi asked the design community to decide whether it could “learn something from Las Vegas.” In this talk, Grant McCracken will ask whether there is something to be learned from television (of all things). Based in research he did for Netflix in the fall, McCracken will argue there is a revolution brewing in popular culture that will transform design and design leaders in a fundamental way. This is perhaps the trend of all trends, the most disruptive change in our midst: popular culture is becoming culture. No creatives or creativity will remain untouched. Our question: How can design leaders use this change to make change?

March 30, 2014

The Pepys Now project: How to write a blog people will read in 100 years

[This piece was originally posted in 2005. It got displaced in a transition to TypePad and this meant it lost its connection to the Samuel Pepy's Home Page, a connection for which I was grateful. This reposting will generate a new link and I'm hoping Duncan Grey, keeper of the Samuel Pepy's Home Page, will post the link.]

[This piece was originally posted in 2005. It got displaced in a transition to TypePad and this meant it lost its connection to the Samuel Pepy's Home Page, a connection for which I was grateful. This reposting will generate a new link and I'm hoping Duncan Grey, keeper of the Samuel Pepy's Home Page, will post the link.]

Samuel Pepys (pronounced “peeps”) kept a diary for ten years, 1660-1669 (http://www.pepys.info/index.html ). He helps us understand the great fire of London, some of the plague years, the aftermath of the English civil war, and the English navy.

Equally important, he helps us see what life was like. We hear him kicking himself for “carrying my watch in my hand in the coach all this afternoon, and seeing what o’clock it is one hundred times.” A man fretting.

For recording the great and little events of the day, Pepys has been given immortality. We read him still.

There is no shortage of diarists these days, not with billions of blogs on line. But will bloggers find immortality? No. This is not just because there are so many of us. The trouble is we assume the things readers will want to know in 100 years.

There are, for instance, countless blog entries from people experiencing the flu. But what history will care about are all the details that struck us as too obvious or banal to mention.

What the “flu” was like, what we took as “medicine.” The “pharmacy” we got the medicine in. The conversation we had with that man in the lab coat. The advice we got from friends. What we wore while recuperating. What we watched on TV. What was illuminated by that faint light in the “refrigerator.” The idea, for instance, of “comfort food.” (What was it? What comfort did it give?) What we talked about on the “phone.” What “emails” we wrote. What happened to personhood? What was it like to be us, as we lost momentum, as our affairs went into suspension, as our life began slowing to come undone. Where did the mind turn in this rare inactive moment. What fretting did we do?

In 100 years, the flu will be an exotic experience. (We read Pepys for his accounts of the plague; we know longer know what this was like.) Historians will hold conferences on the experience of sickness and curing. And they will consult our blogs mostly with unhappiness.

A conference paper in the year 2103:

We have 3.74 million references to “flu” in the blogs of the early 21 st century. We have the medical accounts of what it was and what curing was. But we do not know what it was like as an experience.

These bloggers were talking to one another. They were not talking to us.

But I am happy to report that I have discovered one web log that offers a meticulous record, one might even say Pepysian account, of one flu in one life.

Using the weblog entries of one Sarah Zupko , I intend to show how the “flu” worked as a social, cultural, emotional, physiological and medical event in the life.

With this as my platform, I will seek, then, to illuminate key aspects of everyday life. Sarah Zupko ’s account of the flu she suffered in the 14 th week of their year 2003, in conjunction with other records we have at our disposal, help us to see how the “self” was constructed, maintained and, in a word, lived.

In an odd way, we owe this now vanished virus a debt of thanks. Under its duress, Zupko was moved, meticulously and with rare sensitivity, to reveal not just what it was to be “sick” but what it was like to be a creature of this historical and cultural moment.

Blogs for their time

There are two strategies here.

The first is simply to document everything we can and let history do the sorting. In the case of “blanket documentation,” we don’t need to choose because we seek to capture everything.

1. The blanket documentation: a week’s regime

(do this once a year)

Monday:

Recording place:

Photo documentation:

Home, work, neighborhood, local store(s), other places we go,

Do 5 level of documentation from broad to the individual object

(e.g., our neighbourhood, house/apt., rooms, objects, contents)

Tuesday:

Recording time:

Prose documentation

Structure of the last week

Things that were scheduled

Things that were spontaneous

Who, what, where, when, and why of each event

Wednesday:

Recording things:

(Clothing, furniture, art, fridge magnets & other possessions)

Photo documentation

Prose documentation

Link the two, prop a photograph of your favorite sweater in front of the computer and describe where it comes from, where you found it, things that happened as you wore it, what it means to you know, how it interacts with other articles of clothing, the last time you wore it and anything else it brings to mind

Thursday:

Recording media:

Music, movies, television, websites

The regulars

The occasionals

The discoveries

Prose documentation of and for each.

Friday:

Recording people:

Diary entries:

Video documentation

Do interviews with everyone who will put up with one. Set up your video camera (if you have one) and leave it standing in the living room (if you have one). When someone comes over, sit them down and ask them these questions… and anything else that occurs to you, and capture anything else that occurs to them.

Saturday:

Review, reflect, spot holes, capture the things we’ve missed

Sunday:

Review, voice over commentary on each of your bodies of evidence. There are two imperatives here:1) capturing the assumptions that did not get onto film and that do not normally get into blogs; 2) showing the interrelationships of all the pieces we have know documents. What are the wholes that organized the parts? What was the lived experience of this world

There will be moments when you’ll think to yourself, “Oh, what’s the point, this is so obvious.” But think about what you would give to have account like this from your life, say, 20 years ago. If would be a dear possession. Think about what you would give to have this account of your father’s life when he was the age you are now. Think about what you give for an account of your great, great grandfather’s life. By this time, you have materials that historians would be pestering you to have a look at.

The “as if from a glass bottom boat” documentation

This is the second strategy. This is the documentation of a single thing, person, place, object, event. It could, for instance, be the flu. Now the trick is to tear ourselves away from the familiarity that, blessedly, makes so much of our experience intelligible and manageable. Only thus can we deliver what historians want (and what we will be pleased to have in 20 years).

There are a couple of aids here. One is surprise. Surprise occurs when assumptions are violated and it represents an opportunity to capture what these assumptions are. I was standing in Grand Central Station last week and a man passed me wearing a burgundy red fedora. It was too stylish to be a prank, too odd to be a simple act of style. It forced me to think about hats and to see the conventions that govern them.

Another is humor. This too depends on violated assumptions. Victorian jokes now strike us as not very funny. And this is because we no longer share the cultural assumptions they assumed and on which they operated. Take a moment of humor and supply the archeology on which they rested.

A third is what the Russians called deformalization. The banal example here is repeating a word over and over until it becomes strange to the ear. (Try saying, “saying” thirty times and see if it continues to deliver meaning as it once did.). The trick here seems to be just concentrating on something for long enough that its “taken-for-grantedness” begins to fall away. Think long enough about a kitchen and this begins to happen with surprising ease. (CxC assumes no responsibility for the dislocation that will follow.)

A fourth might be called the Goffman effect. Erving Goffman sought out the company of people who had forgotten or misremembered the rules of everyday life. They stood too close to him.(Ah, so there is a rule that says we must remain 12 to 16 inches from a conversational partner.) They gave too little eye contact or too much. (Ah, so there’s a rule…) They shouted or whispered. And so on. The trick here is to treat social error as an indicator of social convention.

(A fifth is the alienating effects of drugs and alcohol, but CxC is forbidden from recommending this path to illumination.)

What we really need here are pen pals in mainland China , correspondents who read our accounts and say, “sorry, I still don’t see how this person, place, event, or thing made sense to you.”

Storage

Once you have performed your Pepys scrutiny, burn it on a CD or DVD and send one copy to the youngest responsible member of your family, with careful instructions that they are to do the same in 20 years. Send the other to the Smithsonian. Congratulations, you are now immortal.

March 28, 2014

Tweeting television (now locked in a box)

I have a friend who believes every article, post, tweet he needs to read will come to him every day by new media.

I have a friend who believes every article, post, tweet he needs to read will come to him every day by new media.

And he’s right. We act as editors for one another. We see something, we say something…on Twitter, Facebook, Tumbler, LinkedIn and elsewhere.

But he’s wrong. I bet he misses things. I know I do. Plus, some things can’t get into new media. They just don’t.

Take TV. We watch a lot of TV. And my Netflix research winter tells me that we watch this TV with new attention to detail and a deep inclination to talk about it. We find favorite scenes, brilliant bits of acting, very special effects, but all of this remains locked in the box. It just isn’t ”spreadable,” to use the language of Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford and Josh Green. (That’s their book cover above. Highly recommended. Forgive the Italian subtitle. Buy the book here.)

This is a classic case of the old media failing to seize the opportunities opened up by new media. Imagine how many of the shows that failed this fall season might have made it if their early fans could have got the word out.

What we need is some tech overlay that makes clipping and sharing easy and possible. Build it into the remote control. Put on an IN button and an OUT button and a CLIP button and a SHARE button.

I am sure there are legal issues here, but I am equally certain Lawrence Lessig or Jonathan Zittrain could sort them out over lunch time. The copy right holders are, after all, deeply incented to permit the passage of small clips. Permit? What Jenkins, Ford and Green say about spreadable media, applies especially to every new season of television. If it doesn’t spread, it’s dead.

In the meantime, we can resort to efforts of our own. Here’s a clip from one of my favorite shows, Being Human. This is Sally, a ghost, explaining how she intends to protect the house from sale. (Remember, she’s a ghost and therefore invisible to mortals.)

I shot this with my iPhone. Something less that stellar quality. But good enough for the internet, as they say. Some people are put off by Being Human because it’s on SyFy (they don’t like science fiction) or because the show has such a weird premise (the creatures “being human” are a ghost, a vampire, and a ghost). But I think this scene takes us beyond odd premises into the heart of the show. Several “barriers to entry” fall. SyFy wants this clip to click.

God knows, we have quite a lot of content circulating on line. The numbers are simply breathtaking. But the fact of the matter is that TV preoccupies us. And it’s getting better. As it stands, this part of our culture is excluded from the conversation. This should change.

March 27, 2014

Secret messages in Fringe

A couple of years ago, I did a post on a “secret message” I discovered in a show called Fringe. This show has disappeared from the airways, and so, somewhat less tragically, has my post.

So I am reposting the images in question. They were shot by me, using my DVR. The image in question appeared on the screen for no more than a frame or two.

This could have been a technical error, but almost certainly it was a secret message from Fringe show runners, a Valentine, no less.

This sort of thing would have been unforgivably unorthodox in the world of TV just 5 years ago. Now, it’s possible. And for Fringe fans, a small treasure.

Here is the screen without the secret image:

Here it is with the message in place:

Hard to see? Of course, it is. It’s a secret message.

Period Piece

There is a great essay in Pacific Standard by John Gravois. It should be read for its sheer skill and evident pleasure it brought the writer, then the reader. But I couldn’t help looking at it anthropologically, breaking it down alphabetically, as above.

A Author spots something in the world (artisanal toast)

B Author tracks trend to point of origin in the world (Trouble)

C Author discovers the originator (Giulietta Carrelli)

D Author discovers the origin myth which proves to have 3 layers:

D1 Carrelli as a Berkeley students conducts a culturematic experiment in the street, discovers the magic sociological properties of toast

D2 Carrelli wanders in the world before discovering a very wise man (Glenn) on a beach who gives her essential advice (he is the Buddha CA style, hence his name)

D3 Toast and Trouble prove to be a very good solution to a deeply personal problem, Carrelli’s psychological affliction

E This is the trajectory of so much cultural meaning in American culture. It begins as a personal invention, created for personal reasons, and then it finds its way by logical and diffusion stages into American culture, installing itself in our lives, as a much more public, but still resonant, meaning. The personal becomes the public becomes the personal. Think Z-dogs skating abandoned houses in southern California. Think Alice Waters. Think Lou Reed. Think Pete Seeger. Some film makers. Most novelists. All poets.

And I love how well this essay works as an essay. This may have something to do with the double construction. Gravois’s quest becomes a study of her quest. Gravois gives us an artisanal treatment of her artisanal treatment. The mythic construction. that’s evoked, not inked. The “just so” quality of the story, how inevitable it feels. Fragile, perilous, but necessary.

(This is a nice thing to reckon with: necessary things that seem implausible and barely possible. Maybe that’s the post hoc at work. In the early 1970s Alice Waters’ revolution seems implausible. But these days it now feels like something that had to happen.)

It’s fun to think how much American culture comes from the personal. From individuals making cafes called Trouble and authors discovering them in essays called Toast. Apparently, we have pipes down everywhere, there to capture innovations and bring them to the surface. Meaning as energy. I’m not sure we know enough about this process. This is the social face of innovation. We know how bags of data and thinking on technological and business innovation. But the social stuff, that’s less clear.

Last thought

Sorry for the graphic. I thought it would work as a kind of a road map for the post. But really it just ends up looking like one of those combination locks on the driver’s door of a mid size, turn-of-the century GM automobile. Sorry. I really will have to talk to the guys in the lab. Design, this is not something they know from.

March 26, 2014

Head Starts: creative platforms for culture makers

I was reading a great post on fan fic and was struck by this phrase.

“When the stress of world-building goes away, it’s easier to let words flow.” http://bit.ly/1gq0nyl

And the obvious struck me. (I’m one of its favorite targets.) The cunning of fan fic is that it passes off the hard work of origination to someone else and allows the writer to take up residency in a ready made world. The stress of world building does go away.

One of the things that impresses me about the 1950s is that an awful lot of people on Madison Avenue had a novel in the drawer. And not just any novel. Everyone was hoping to pen the great American novel.

This novel was many things, a ticket out of your career as a copywriter, an apology for working for “the man,” and, not least, an opportunity for immortality.

But it was a fantastically tough assignment. You had to start from zero. Before you could write a word, you had furnish your novel with assumptions, architectures, infrastructures, presuppositions, characters, events, narrative arcs. You had to build an entire world. And this is precisely why so many of those novels never got written.

The genius of fan fic is that you just move in to someone else’s world. Most of the heavy lifting is done. To be sure, you are not the captive of this prefab world. You can change anything you want. But your creative platform is in place. Your readers are “half way there.” And perhaps most important you have a community of fellow fan fic writers who are also rehabilitating Star Trek or Elementary. This is a community of problem-solvers from whom you can draw when you are not astonishing them with your brilliance. Competitive collaborative creativity, like.

This is the cultural version of the thing we have seen happen in the technological and start up community. I recently heard x and y give a talk about how much more code is available to hand every time they start up another startup.

Like the post yesterday, this encourages two points.

One, that we are more productive when we work with creative materials in place, a starter kit, so to speak. Starting from zero was an avant garde conceit. It was why novelists were obliged to retreat to garrets and torment themselves with months of solitude. Not us. We just drop into any existing property, take the money and run.

Two, this is where the value is. We have thousands of people poised to innovate and create new content. And sometimes it’s true that another app is exactly what the world wants. But more often, and more thrillingly, what the world wants is a creative platform, like fantasy football or fan fic, that gives us materials with which to work, a place to start, a platform and infrastructure. We have the creativity. We have a deep knowledge of culture and how to make it. What we do not have is an infrastructure that takes this work into the world, there to

All those TV shows and movies have supplied this head start. But they have done so accidentally. I wonder if there isn’t a species of capitalism that could go at this more deliberately. We need an industry of raw materials. We need an economy through which culture creators can be compensated. We need platforms through which value flows.

Acknowledgements

Art used by kind permission of Stanley Chow. See more of his remarkable work at his website here. See the Offbook PBS special “Fan Art: an explosion of creativity” in which his work is featured here.

It would be too cruel an irony to talk about compensating people for their work on line and then give Mr. Chow nothing so much as a “thank you very much.” As it happens, starting today I noticed Google gmail and Google wallet now make it really easy to attach sums to an email. So I sent Mr. Chow 5 bucks. It’s not much. And it makes no claim to ownership of his art. It is merely meant as a way of saying “thanks.” (We really need a tipping system for work on line. We really do. )

March 25, 2014

Recasting culture (and especially TV)

There’s a small trend in the works. People are daring to recast popular shows on TV. In the image above, Entertainment Weekly dares imagine the new detectives for True Detective. Here Ryan Gosling and Denzel Washington are proposed as replacements for Woody Harrelson and Matthew McConaughey. (Apparently, HBO and or Nic Pizzolatto had always planned a modular approach for the starring roles.)

Digital Spy undertook the same recasting, proposing Ian McKellen and Patrick Stewart as the new True Detectives. This would count as irresistible TV, in an era of irresistible TV.

Grantland took the thing a step further, proposing a fantasy league for Hollywood.

There is a quite wonderful book called Culturematic that suggests a way to recast NCIS.

The idea is everywhere. Ok, not everywhere, but this is a gusty little trend breezing its way through contemporary culture.

This shows a new order of participation in culture. It’s hard to imagine this sort of thing happening in the 1950s when people took what TV deigned to give them and were grateful for it too.

But people now new and deeper knowledge of popular culture and they are eager to use this knowledge. Exactly this sort of thing happened in the case of professional sports. The inventors of Fantasy Football believed that only sports journalists would want to participate. What they didn’t see was that sports fans had read so much sports journalism, that they too were itching and able to participate.

This relates I think to yesterday’s post on Pharrell’s Happy video where I suggested that crowd sourcing talent is not always successful. But here when we ask people to engage not as actors but as critics that the chances of success go up. Its as producers and directors that we are most interesting, productive, and engaging.

We should also observe the presumption at work here. One of the reasons that viewers in the 50s wouldn’t engage this way is that it was presumptuous to do so. Creative decisions were things made by experts in big cities, people and worlds away from their own.

But now we are, to use the Tudor phrase, “over mighty subjects.” We take for granted our right to second-guess creative decisions. Our knowledge of culture is not passive but active. This means that even as we consume culture, we expect to produce it. If only in our heads. If only in the conversation we have with friends and family. Anyone who finds a way to engage us in this way (we shall keep an eye on Grantland’s fantasy league) is creating value for us and value for themselves. (Thus do anthropology and economics intersect.)