Grant McCracken's Blog, page 15

May 1, 2014

Contemporary culture: 25 years of change in 15 minutes

In the early 1990s, I founded and ran the Institute of Contemporary Culture at the Royal Ontario Museum.

On Saturday, I’m going back to the ROM to reflect on some of the changes that have taken in culture in the last 25 years.

And it’s dizzying to see how much is now changing: the home and the family, the way we think about women, the revolution taking place in TV, the way we are now defining the self and the group. (I have just 15 minutes to talk, so it’s a short list.)

As you will see, this presentation is less about technology (the thing with which most people lead nowadays) and concentrates much more on the cultural changes that have taken place. These are, I would submit, every big as large and astonishing as the tech changes.

You can see the presentation here on YouTube. Like most everyone, my speaking style has shifted from too many words on the screen to images. The burden of exposition falling to the speaker (me) when speaking (on Saturday). Apologies when this makes the deck a little cryptic. Please do come join us if you are in Toronto this weekend.

April 29, 2014

Chris Rock teaches a course on ethnography

America has a tradition of interviewers who can’t really interview. I think it may start with Johnny Carson. It got worse with David Letterman. It may improve with the new lot on late-night. We shall see.

America has a tradition of interviewers who can’t really interview. I think it may start with Johnny Carson. It got worse with David Letterman. It may improve with the new lot on late-night. We shall see.

Of course it’s wrong to ask comedians to interview well. Their job is to find the funny and pitch the film. There’s no time to ask a real question, no chance to open a view corridor on the guest.

But surely, we are a little sick of Hollywood “personalities” and would cheer the host who could occasionally crack open that polished candy coating called celebrity for a glimpse of the person within. Is it too much to ask for the occasional question that goes the heart (perhaps even the soul) of the guest? What could it hurt? As prime time TV gets better, surely late-night could improve a little too.

Which brings us the Chris Rock documentary called Good Hair. This is not late-night, but it could make a real contribution to late-night (and anyone else who wants to learn how to be a better ethnographer).

Good Hair is filled with great interviewing. The camera takes in Rock occasionally and while there is no question that he is aware of the camera and no question that he is sometimes playing to the camera, we catch him listening well (as pictured).

There are several enemies of ethnography. One of these is self absorption. Vain people can’t ask a question that has any hope of revelation because they only care about themselves. They are dark stars, their curiosity never escapes the gravitation field of their own egos. All questions bend back on the bearer.

The other enemy of ethnography is self dramatization. Think of John McLaughlin, all bluster and tough mindedness (and no trace of nuance or thoughtfulness). The interview is merely a platform for the McLaughlin performance, and this is now tedious.

It may be that Chris Rock is already a big enough star that he doesn’t need to commandeer the interview for his own purposes. In any case, he doesn’t.

In Good Hair, Chris Rock demonstrates one of the really interesting moments of the interview, that moment when the ethnographer isn’t exactly sure what he’s asking and the interviewee is working hard to answer but doesn’t quite know what he/she is answering, and neither party is fully in control of the interview.

A guy like Larry King wants to keep things tidy. The questions are crisp. And answer are crisped. King fields a answer and bangs off the edges, the imprecisions, the glimmers of some other meaning. And, to be fair, this is the obligation of the old TV, to make things indubitable.

But things have changed. Imprecision is forgivable. It is indeed an opportunity. You the ethnographer are not sure what you are asking. You can just feel something out there beyond the scope of the interview. And the interviewee, bless him/her, shares the intuition and is prepared to go looking. Even if this means being a little vague for a moment.

There are several moments in Good Hair when the interview just floats. Rock and his respondents are waiting for answers to form. Sometimes, there’s silence. What we can hear is people struggling to figure out how to think about this, how to talk about this. These are delicious moments. This is how you capture culture.

Clearly, it helps a lot that Rock is talking about a topic (hair) that is not much talked about. It’s a topic surrounded, he discovers, by prohibitions. People don’t talk about it. Even to themselves. Coaxing this kind of knowledge out of its prohibited space is always interesting, and to get in on camera is really superb.

We are a culture enamored of ethnography. And we are surrounded by bad interviewing and terrible interviewers. Those of you looking for a short course on ethnography might consider watching Good Hair.

April 28, 2014

Cultural arbitrage

This video by Ingrid Michaelson, called Girls Chase Boys, uses this video by Robert Palmer called Simply Irresistible.

If intellectual arbitrage is the movement of meanings or models from one academic field to another, cultural arbitrage is the movement of meanings or models from one part of culture to another.

So Michaelson moves the theme, the meme, the dream out of Palmer and uses it for new purposes. Men become sexual objects (where before it was women). Michaelson describes an independence from men (where before it was Palmer claiming a “dependence” on women). The idea of a sexual object is put in play. Our culture changes course…a little.

This is a complicated maneuver. A cultural artifact is being created out of existing cultural materials. With a twist. Meanings are being lifted, changed and reapplied. (Something burrowed, something blue.)

Sampling is the simplest example of cultural arbitrage. Jay-Z took a show tune from the Broadway production of Annie and dropped it into his song “Hard Knock Life (Ghetto Anthem).” This is not the first thing you would expect to hear in the music of self proclaimed “Marcy Projects hustler” but it worked beautifully, giving a strange vitality to both the song and the sample.

Michaelson had finished her song when she saw the Robert Palmer video and went, “oh.” Somehow you just know at once that something when transplanted will give off new meanings.

The academic world has spend a lot of the time thinking of cultural arbitrage as a matter of “appropriation.” Who owns the original? Is this originator properly acknowledged and compensated? This is an important question…though I am not sure why we felt we had to devote the whole of the 1990s to talking about it.

But the bigger, more pressing question is how to take advantage of cultural arbitrage. The Onion does a fine job. After all, most metaphor and a lot of humor turns on arbitrage.

If I may quote myself, here’s what I said in Culturematic about what may be my favorite example of arbitrage:

Some years ago, The Onion pictured Alan Greenspan and his Federal Reserve Board team destroying the penthouse of the Beverly Hills Hotel. In their “coverage,” The Onion gives us a dispassionate treatment of televisions being kicked in, mattresses hurled from the balcony and the inevitable police intervention.

“Monday’s arrest is only the latest in a long string of legal troubles for the controversial Greenspan, who has had 22 court dates since becoming Fed chief in 1987. Economists recall his drunken 1994 appearance on CNN’s Moneyline, during which he unleashed a profanity-laden tirade against Bureau of Engraving & Printing director Larry Rolufs and punched host Lou Dobbs when he challenged Greenspan’s reluctance to lower interest rates. In November 1993, he was arrested after running shirtless through D.C. traffic while waving a gun. And some world-market watchers believe the international gold standard has still not recovered from a May 1998 incident in which he allegedly exposed his genitals on the floor of the Tokyo Stock Exchange. The Tokyo case is still pending.”

Thus did The Onion bring together two things: the dour keeper of the economy and the self-indulgent chaos of the rock star. It performed a careful act of transposition. Every line of The Onion “story” is lifted from a typical newspaper report. Journalistic details are lovingly preserved. (“The Tokyo case is still pending.”) Only the names and occupations are changed.

Some of the power of cultural arbitrage comes from that double movement it inflicts on us. As when we read this passage, the meaning takes and then fails. We transfer the meaning and then stop transferring it. We say, “Yes, got it. Greenspan as a rock star” and then we say, “No, this is impossible. I can’t think this!”

Arbitrage is an engine of creativity. And often the trick is to bring together parts (aka meanings) of our culture that rarely go together. As in the case of this account of the Fed on a rampage. It takes an outrageous act of imagination to glimpse the possibility. And then we delight in the difficulty of thinking it.

But some cultural arbitrage comes from much smaller, more subtle acts of comparison. Finally, we can collapse this strategy to the vanishing point. As when Stephen King talks about the horror of discovering that everything in a home has been replaced with a perfect replica. No real difference, accompanied by a whiff of oddity, this is the small act of arbitrage, but it carries, as King shows, big effects.

Popular culture is in the arbitrage business, as one actor is cast against type, or a picture is made to migrate across genres. Morning television is in the arbitrage business when it puts Charlie Rose, Gayle King and Norah O’Donnell in the same studio. It’s the differences and the emergent harmonies that make this show work while others struggle.

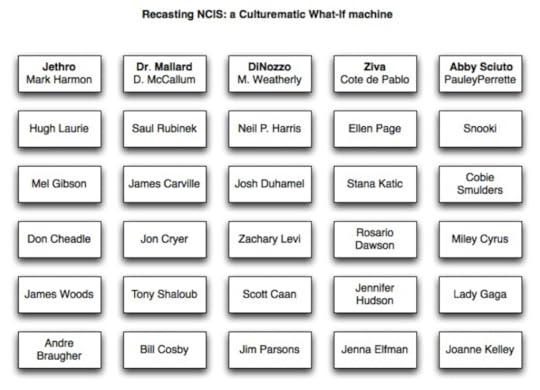

Speaking of TV, here’s another outtake from Culturematic. It shows a casting machine for NCIS. The idea here is to see what difference a different set of actors would make. The sweet spot is in the middle of the chart. (Don Cheadle territory). The alternatives close in are insufficiently different to release much frisson. The ones far out (towards the bottom of the chart) are too different for the narrative to hold.

We spent so much time debating appropriation that we have yet to make a systematic study of cultural arbitrage. But this is one of the workhorses of contemporary culture. And with conscious study we can make it still more productive.

April 25, 2014

Cats, cigars and other secrets of innovation

My wife is taking a course in brainstorming, she told me today. And I’m sure it will be useful. I once took a course in brainstorming and it helped a lot.

But I couldn’t help thinking that sometimes creativity doesn’t need a group or a storm. It doesn’t need a process or a method. All it takes is a cat or a cigar.

I ran across this paragraph from the Wikipedia entry for Reginald Fessenden (1866-1932), a Canadian inventor and personal hero. (Fessenden is famous for having applied to work with Edison, remarking, ”Do not know anything about electricity, but can learn pretty quick.” Edison replied, “Have enough men now who do not know about electricity.”)

“An inveterate tinkerer, Fessenden eventually became the holder of more than 500 patents. He could often be found in a river or lake, floating on his back, a cigar sticking out of his mouth and a hat pulled down over his eyes. At home he liked to lie on the carpet, a cat on his chest. In this state of relaxation, Fessenden could imagine, invent and think his way to new ideas, including a version of microfilm, that helped him to keep a compact record of his inventions, projects and patents. He patented the basic ideas leading to reflection seismology, a technique important for its use in exploring for petroleum. In 1915 he invented the fathometer, a sonar device used to determine the depth of water for a submerged object by means of sound waves, for which he won Scientific American’s Gold Medal in 1929. Fessenden also received patents for tracer bullets, paging, a television apparatus, turbo electric drive for ships, and more.”

“An inveterate tinkerer, Fessenden eventually became the holder of more than 500 patents. He could often be found in a river or lake, floating on his back, a cigar sticking out of his mouth and a hat pulled down over his eyes. At home he liked to lie on the carpet, a cat on his chest. In this state of relaxation, Fessenden could imagine, invent and think his way to new ideas, including a version of microfilm, that helped him to keep a compact record of his inventions, projects and patents. He patented the basic ideas leading to reflection seismology, a technique important for its use in exploring for petroleum. In 1915 he invented the fathometer, a sonar device used to determine the depth of water for a submerged object by means of sound waves, for which he won Scientific American’s Gold Medal in 1929. Fessenden also received patents for tracer bullets, paging, a television apparatus, turbo electric drive for ships, and more.”

We can’t organize or manage ideas. We can’t regiment creativity. But as innovation becomes increasing the first business of business, and the way we hope to survive a turbulent world, we are inclined to force the issue.

Cigars have gone out of fashion. But are we spending enough time with a cat on our chests?

April 24, 2014

Bosco and the memory of William Drenttel

A couple of days ago, I wrote about Bosco, the 8 year-old who knows all about meth labs and not a lot else.

I got precisely one response, a woman who said this was kind of problem she likes to solve. And that was it.

I thought, “maybe if I develop the idea a little.” My first idea was a kind of twinning project. You know, the kind that cities have. ( New York is a sister city to Cairo.)

We would identify 6 kids across the US who would then become Bosco’s twins. And we find away to capture what they are learning as they are learning it and we find some way to communicate this knowledge to Bosco.

Our objective is to make him cosmopolitan in the ways that they are cosmopolitan. (And by “cosmopolitan,” I mean merely, “knowledgeable about the world outside one’s own.”) My assumption: that there are many disadvantages to growing up in the home in which Bosco finds himself but one of the most debilitating is a lack of knowledge/understanding/awareness. (Call it “cultural capital.“) This lack of knowledge is, we could argue, more damaging than illiteracy or innumeracy.

Problem 1. There is a “barrier to entry” problem here. As meth cookers, there’s a good chance that Bosco’s parents have limited horizons (prima facie case, no?) and that they would not welcome the intrusion of a system that is designed to broaden the horizons of their son.

I don’t how to solve this problem. I have a feeling that an anthropologist and an economist working together, with the levers of meaning and value, could come up with a solution, but more on this later.

Problem 2. There is no question that this twinning process, if it worked, would transform Bosco and there’s not much doubt that it would estrange Bosco from his family. This would make Bosco the captive of a hostile environment. From the parental point of view, we have created a “little Lord Fountleroy,” someone who thinks himself (or is thought to think himself) better than his family.

I don’t know how to solve this problem either. It’s worth pointing out that every immigrant and upwardly mobile family find themselves with kids who are more cosmopolitan than their parents. And these parents find a way to deal with it.

Mind you, these people have sought the condition they endure. Our “meth” mom and dad accomplish that magical contradiction that allows them to refuse the idea that they are not cosmopolitan even as they resent those who are.

How do we reach them? What do we say? Could we construct a forgivable space, a status allowance, for Bosco in the home, one that allows his parents to say, “Oh, don’t listen to him. He’s our little Martian. Always talking about the craziest stuff!” (Yes, but of course, we could hope for something more than this but I think it’s wise ((and not particularly hostile)) to assume the worst. We are not looking for perfection. We just want an allowance.)

The trick is making it “our little Martian.” We need to construct a status for Bosco in the home that gives him room to take on and give off cosmopolitan knowledge. And this will depend on constructing a status that allows his parents to forgive, and perhaps even take credit for, their oddball son.

At this point, I need to address a tide of unhappiness that I know is rising in anthropological readers (and some others). People will complain that I am “essentializing” Bosco’s parents and Bosco himself, that I am imputing characteristics in an act of class stereotyping and status diminishment, that this is an exercise of power.

Allow me to do an anthropology of the anthropologists (and engage in another act of classification). Anthropologists are almost silent when it comes to the big problems of our day and that is because the field is largely preoccupied by acts of self criticism. Hand to brow, with a show of their sensitivity, they ask, “Can we generalize? What are the politics of generalizing? What are the ethics of generalizing?” These are real questions. But Anthropology is now effectively an amateur theatre company dedicated to a production of moral posturing and ethical declamation.

I am not saying these cautions do not matter. They do. But when they are the only thing you do, when they are the thing you do instead of helping a kid like Bosco, when they are the thing you do that prevents you from helping a kid like Bosco, I say this. Bite me. Get over yourself. Snap out of it. Start again. Your trepidations matter less than Bosco’s future. While you posture, pain and suffering flourish like the green bay tree.

Whew! Sorry. Anthropologists have to stop being too good for the world. It’s the only way they can return to usefulness.

One way to address Problem 2 is to catalogue all the instances of families in which children are marked as different, where parents are called upon to explain and, we hope, make allowances. Families with autistic kids, for instance, sometimes resort to calling them “little professors.” There are other precedents. What are they? Are any of them usable here? How would we adapt these?

Let’s say we solve Problems 1 and 2. Let’s say we find a way to create a twinning system and relay information from Bosco’s twins to Bosco himself. How would we do this?

This is where I thought of William Drenttel. I gave a paper at Yale a couple of years ago and afterward he and I had a roaring, gliding conversation. It was clear he was trying to recruit me for one of his grand schemes and to my discredit I failed to rise to the occasion. (I was working on schemes of my own, which I now see were minor and ordinary by comparison.)

When I thought about how to get information, knowledge and understanding to Bosco, I thought of Bill. He is one of those designers who strike me as the anti-anthropologist: citizens of several worlds, effortlessly mobile in passage between them. Bill, I thought, would know how to think about this problem. This is a design thinking problem because we are, in effect, being asked to design thinking.

If we could find some way to represent the knowledge being accumulated by Bosco’s twins, this might help. Let’s say Twin 1, the one in Philadelphia, is sitting with his family watching TV. There’s a news story about LA and the family conversation that follows somehow puts LA on Twin 1′s “mattering map.” (I have this term from Rebecca Goldstein).

The trick now is to make LA matter on Bosco’s mattering map. The fact that we are talking about geographical knowledge helps a lot. A map is itself a useful, perhaps the original, visualization. But our job is to show how “LA” matters not just for its relative location (Bosco lives somewhere in the midwest) but also as the home to Hollywood, dinosaur-rich tar pits, several sporting franchises, and a particular place in the American imaginary. (We will have to fit that last one with new language.) Our question: What does Bosco already know and how do we use this to help him grasp facts and fancies about LA.

Bill, I thought, will know how to take this problem on. And today I discovered that William Drenttel passed away in December of last year. (See this remarkable obituary by Julie Lasky.) I think an honest, hard-earned moment of self repudiation is called for here. Why wasn’t I in touch with him? Why didn’t I know about his illness or his passing? Is there some good reason why I live like a small forest animal, posting out of a tree stump and otherwise out of touch with the world? What is my excuse exactly? And who am I kidding? (Forgive a maudlin outburst.)

My thought originally was to make designers and anthropologists the intermediaries of the movement of knowledge between Bosco and his twins. But in a more perfect world, and now with social media at our disposal, it might be possible to make Bosco and his twins a tiny community (Marshall Sahlins’s “mutuality of being“) that pools its knowledge and helps one another master it. Can eight year-olds do this kind of thing? I don’t know. Maybe with some training.

Happy coincidence but this morning I saw a tweet by Sara Winge on the attempt by UNICEF to use Minecraft to show what a reconstructed Haiti might look like.

Could a band of eight year-olds build a model of their knowledge? In Minecraft or some other medium? Jerry Michalski has put some of his knowledge online. Some 160,000 “thoughts” all in categories and ready to hand. Bosco and his friends might do the same with the right education and encouragement.

There is lots of work to do here. Who’s interested? If we get something up and running, I propose we call it the Drenttel project. No, there are so many Drenttel projects running in the world, that would be wrong and clueless. Let’s call it A Drenttel Project.

Acknowledgment

Thanks to Kevin Smith, William Drenttel and Architect’s Newspaper here for the image of Bill above.

April 23, 2014

A celebrity lab by celebrities for celebrities

I read somewhere recently that Judy Greer has a way to categorize her fans. So when she sees them in public, she can tell who she’s dealing with.

I read somewhere recently that Judy Greer has a way to categorize her fans. So when she sees them in public, she can tell who she’s dealing with.

Perfect, I thought. It’s about time celebs turned the tables. We spent a lot of time talking about them. They dominate TV, many magazines, and much of the chatter on-line. It’s about time they started studying us.

A celebrity lab by celebrities for celebrities would be a good idea for strategic, entirely self-interested reasons. However much it may feel like their celebrity is inevitable, fame is something conferred by the fans. And what the fans give, the fans can take away. Ask Alec Baldwin, Gwyneth Paltrow or Matt Lauer.

Celebrities could start with a typology of fans. And there is a lot to categorize. Some fans are deeply scholarly. They can recite the biographical details, film titles, dialogue. Some merely prize a particular film character. ”I loved you in A Walk on the Moon!” Others just happen to be in love with the Star Wars or the Spider Man franchise and you are sudden, irresistible opportunity to make contact. Still others are merely excited because they are in the presence of someone famous and people are screaming. Still others are just screaming. Distinguishing one from the other would be a good thing. Having a strategy for each of them would most helpful.

There is also, of course, a dark side. There are those who make a great noise but are essentially harmless. Others are stalkers in training. And still others are so dangerous, the right thing to do, the only thing to do, is to take cover as quickly as possible. Early warning here would be unbelievably valuable.

The celebrity could assume that everyone they meet in public is a nut job and armor themselves with beefy security guards. But in fact public appearances, even impromptu ones, are part of the job, the way you renew your celebrity. Really, the celeb has no choice to expose him or her self to interactions with the public.

So celebrities really need a way to tell who they are dealing with, on sight, in real time. This person I see before me, the one grinning ear to ear and making a high pitched sound, is this a goof ball or a psychopath? A typology would help.

I got to see celebrity at work when I was the chauffeur for Julie Christie for the filming of McCabe and Mrs. Miller. She was so famous at this point that Life magazine had declared 1965 “the year of Julie Christie.”

One afternoon, Julie and I were in a candle store. We happened to be standing beside some guy who couldn’t decide whether his gift candle should be lemon or lime. Julie volunteered that the lemon might be quite nice. The guy turned to thank her for this advice but as it dawned on him that the speaker was the most famous woman in the world, he found he had no words. He walked out of the store, both candles in hand.

This is the best case of celebrity. Your charisma protects you from contact, smoothes your path, charms your existence.

But there were other moments when people would come up to us and barge into Julie’s personal space. I didn’t quite know what to do. You couldn’t tell whether this was a friend she didn’t recognize or a hostile she ought to fear. Scary as anything. And there would be this unpleasant moment when we would have to wait for the person to throw off a little more information, so that we could figure out who they were and what they wanted. And in that several seconds, we were vulnerable.

So some system for identifying strangers and a set of strategies for dealing with them would have been a very good thing. Go, Judy, go. And if you need a team of anthropologist to work on this problem, call me. I could put together a set of teaching materials and conduct a lab. It would be like teaching in the Harvard Business School classroom again except I wouldn’t have to memorize anyone’s name.

April 22, 2014

Orphan Black and cultural style

Readers of this blog know that I’m a fan of the show Orphan Black on BBC America (Saturdays at 9:00). It resonates with the transformational and multiplicity themes so active in our culture now. See my post here.

I finally got to see Episode 1 of the new season (2) this morning and I was captivated by this scene.

Apologies for the quality of this clip. I shot it with my phone. Perhaps the show runners Graeme Manson and John Fawcett would consent to put the original up on YouTube. (In fact, the last moment of this clip shows Manson and Fawcell in a Hitchcockian turn. Manson is the camera man. Fawcett is the the man in the glasses.) (See the whole of this episode on the BBC website here.)

I think this clip touches on a couple of recent posts, especially the one on Second Look TV and the one on “magic moments.” You decide.

But the real opportunity here is to comment on a truth in anthropology. My field is, among other things, a study of choice. There are so many ways of being human, of acting in the world, that people must choose. (There is a famous story about a Russian actor proving his virtuosity by delivering the word “mother” in 25 distinct ways.) How will we say a word, make a greeting, or carry ourselves? We have to choose. There are, for instance, lots of ways to do a “high 5.”

We have to choose from all the choices and once we choose we are inclined to stabilize the choice and use it over and over again. It may shift with the trend, and we alert to these shifts, but for the moment, an invisible consensus says, this is how we do the high 5.

But this is not only a personal choice. We make these stable choices as the defining choice of a nationality, ethnicity, gender, region, class, status, and so on. Eventually, this choice becomes a style, a signature way we express ourselves. It is a way we are identified by others.

Hey, presto. Imagine an actress’ delight. With styles, she has a device with which to tell us who her character is and what her character is doing in any given part of the narrative.

Tatiana Maslany, the Canadian actress who plays the clones, has the exceptional task of delivering the “truth” of each clone even as she must make them identifiably different. But of course she is going to use style.

In this scene, she is giving us Alison, the suburban clone. The minivan, pony tail and jump suit label that identity, but then comes the hard part. To show Alison in all her Alisonness. And still more demandingly to show Alison under duress. (Sarah, the street toughened con-artist clone, can handle herself in a fight. The trick is to show Alison making her response up as she goes along.)

There is lots to like in this scene and, reader, please exercise your “second look” privileges to go back and scout around.

I love the moment when we see Alison spraying and blowing. She is after all a multitasking mom.

I love the ineffectual last tweet that comes when she gets pitched into the waiting van, expiration meets exasperation meets astonishment. Who is this man?

I love the small gesture with which Maslany gathers her composure before leaving the van, squaring the shoulders and fixing her pony tail.

And then the wonderful look of dismissal she gives her captor as she closes the door of the van. Alison is back in possession of her suburban self possession. What’s nice about this among other things is that it shows the Alison beneath the Alison. Yes, her self possession has been shaken by this event but where most of us would be wordless and traumatized, Alison is back.

That last moment of the clip, the one in which we see a brief, Hitchcocking appearance from the show runners, I like as well. There was a time when it would be ridiculous to talk about these showrunners and the movie making master in the same breath. But TV is getting so good these days, the comparison is not far off, and closing all the time.

It’s usual to talk about this Golden Age of TV, but that suggests the TV is now completing its glorious ascendancy. And this just seems wrong. With performances like Maslany’s and shows like Orphan Black, I think it’s more likely that TV is just getting started.

Thanks to the anonymous reader who discovered a naming error. (Now corrected.)

April 21, 2014

Does capitalism have thermals (aka, the evolution of Paramecium, Inc.)

A couple of months ago, I had the good fortune to have lunch with Napier Collyns. Mr. Collyns is one of the founders of the Global Business Network and a man with a deep feeling for the rhythms and complexities of capitalism.

I came home and banged out this little essay. It’s an effort to think about the possibility that “value” goes from the material to the immaterial. A company might begin by making hammers but sometimes it ends up making value that is less literal and more broad.

Does capitalism have thermals?

A bigger picture may be called for when we think about capitalism. In his famous essay, Marketing Myopia, Theodore Levitt encouraged people to ask, “What business are you in?” The question had a strategic purpose: to rescue managers from their literalism.

In the early days of the railroads, managers were preoccupied with laying thousands of miles of track. The next generation devoted itself to making a magnificent delivery system for industrial America. With the rise of the automobile, the truck and the plane, things changed. But the conceptual shoe didn’t fall for management until Levitt gave them a big picture. “You’re not in railroads, you’re in transportation.”

There is perhaps an inevitable developmental pressure. As the world becomes more complicated (and capitalism routinely makes the world more complicated), the ideas with which it is understood must become more sophisticated. One minute we’re laying track. The next, we’re wondering how to compete with things that fly.

The only way to grasp the intellectual challenge is to generalize. This helps break the grip of literalism, the one that says, trains are trains and planes are planes. No, says Professor Levitt, trains and plains are the same thing but only if we move to a higher vantage point.

A second thermal comes in the shape of commodity pressure. In every market, incumbents eventually draw imitations (aka “knock offs”) into play. The incumbent is faced with two choices. It can engage in a “race to the bottom” that occurs as incumbent and imitator sacrifice margins until everyone finds themselves mere pennies above cost. (Thus does the innovation has become a commodity.)

Or, the innovator can climb the value hierarchy, moving from simple functional benefits that the imitators can imitate to “value adds” they cannot. Thus did IBM find itself challenged by off-shore competitors who offered bundles of software and hardware at 40% of what IBM was charging.

Customers snapped up these cheaper alternatives, only to discover that the commodity player was not supplying the strategic advice and intelligence that came with the IBM version of the bundle. Now IBM had to learn to talk about this value, and to make more of it. They were obliged to cultivate a bigger picture.

Here’s another “thermal.” Premium players traditionally defend themselves from commodity attack by creating higher order value that almost always comes in the form of idea and outlook. Thus Herman Miller, the furniture maker, confronted by an off-shore competitor that was prepared to make chairs for much less, redoubled it’s effort to sell not just chairs but new ideas for what an office could be. This thermal intensified as new commodity players have emerged from China, India, and Brazil.

Paramecium, Inc.

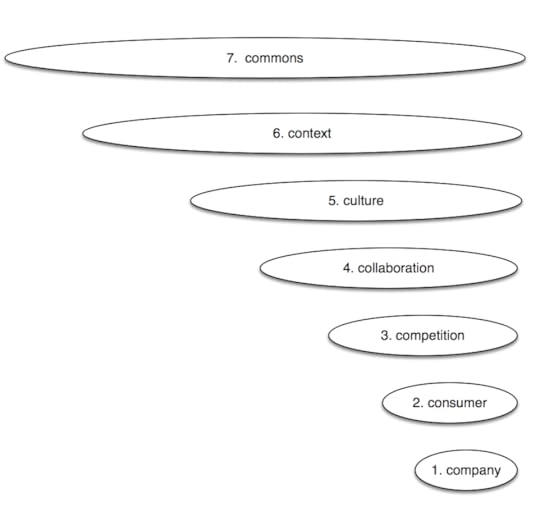

We could argue that capitalism has thermals from almost the very beginning. In this beginning, enterprise were inclined to be structurally simple, a single cell mostly oblivious to the world outside itself. Call this “Paramecium Inc.” or Level 1. The enterprise makes hammers. It assumes someone out there wants hammers but the focus of attention is on the hammer.

Eventually someone comes along and says, “actually, what the company makes matters less than what the consumer wants.” Thus spoke Charles Coolidge Parlin in 1912 when he asserted that the “consumer was king.” Closing the gap between company and consumer has been a work in progress. New methods, theories, and resolve have come from the likes of Peter Drucker and A.G. Lafley, and somehow the gap persists. But at least the Paramecium is evolving, reckoning with things outside itself. This is Level 2.

In time someone says, “we need to think more systematically about our competitors.” This is the long standing focus of Economics, but in the late 1970s, Michael Porter offered a new approach and strategy proved influential. Here too the organization is sensing and responding to the world outside itself. It is scaling not so much up as out. We are now at Level 3.

With each new Level, we “dolly back” to see more of the world. Our “paramecium” is increasing aware of itself and the world outside itself. This is a movement from the narrow to the broader view, from the local to the global, from the provincial to the cosmopolitan.

Level 4, collaboration, has several moments. The enterprise, once less solipsistic, can entertain partnerships. The organization that once insisted on a crisp, carefully monitored border now consents to something that looks more porous. The Japanese influence helps here. So did the “outsourcing” movement. Most recently, with the advent of new media and digital connections, collaboration expands to include still more, and more diverse, parties.

In Level 5, we are encouraged to see that the enterprise must reckon with the meanings, stories, identities, subcultures, and trends with which people and groups construct their world. Noisy and rich in its own right, culture supplies some of the “blue oceans” of external opportunity and the “black swans” of external threat. A great profusion of consultancies and aggregators springs up to cover culture.

Level 6, context, was once merely a field or container for all the other levels. But now the field has come alive, no mere ground but now a source of dynamism all its own. In this bigger picture, the enterprise can feel itself a tiny cork in a veritable North Sea. Disruptive change comes from all directions. Strategy and planning become more difficult, and some enterprises descend into a simple adhocery. The world roils with deliberate change and its unintended consequences.

There is an intellectual challenge at Level 6. Making sense of a world that is so turbulent, hard to read, and inclined to change is difficult. Indeed identifying the unit of analysis is vexing. Are we looking at “trends,” “stories,” “scenarios,” or “complex adaptive system?” Should the enterprise do this work by hiring x, y or z?

“Context” is a wind driven sea. The horizon keeps disappearing, navigational equipment is dodgy, the world increasingly unfamiliar, inscrutable and new. We are to use the language of T.S. Kuhn, post –paradigmatic.

The movement of levels 2 through 4 has been conducted under expert supervision. But Levels 5 and 6 are vexing partly because there is no obvious intellectual leadership. Even the “experts” are challenged. The problem created by Levels 5 and 6 are simply unclear and we continue to disagree on even simple matters.

Reading this through, a couple of hours after publications, it occurs to me that there is for some corporations a Level 7. This is where the corporation embraces its externalities and takes an interest in the larger social good that can come when the corporation thinks about what value it can create for creatures other than itself.

I was in a strategy session a couple of years ago when a guy from Pepsi, I believe he was actually the CMO (let me check my notes), actually said, “I am committing my organization to solving every environmental problem it has in its purview and can get its mitts on.” Wow, I thought, this is capitalism writ large.

April 18, 2014

A new name for this blog

My blog subtitle used to be “This blog sits at the Intersection of Anthropology and Economics.” This was both too grand and untrue. Fine for politicians but not websites.

So now it’s “How to make culture.” For the moment. Also thinking of “New Rules for Making Culture.” Is that better? I can’t tell. Please let me know.

Yesterday, I was blogging about the new rules of TV. And in the last couple of weeks I’ve been talking about advertising, education, late night TV, game shows, culture accelerators. Less recently, I’ve been talking about marketing, comedy, language, branding, culturematics, story telling, hip hop, publishing, and design thinking.

All of this is culture made by someone. And all of it is culture made in new ways, often, and according to new rules, increasingly. Surely an anthropologist can make himself useful on something like this. Anyhow, I’m going to try.

I have four convictions. Open to discussion and disprove.

1) that our culture is changing. Popular culture is becoming more like culture plain and simple. Our culture is getting better.

I have believed in this contention for many years. Certainly, since the 90s when I still lived in Toronto. (It was my dear friend Hargurchet Bhabra who, over drinks and a long conversation, put his finger on it. ”It’s not popular culture anymore. Forget the adjective. It’s just culture.”)

This was not a popular position to take especially when so many academics and intellectuals insisted that popular culture was a debased and manipulative culture, and therefore not culture at all. Celebrity culture, Reality TV, there were lots of ways to refurbish and renew the “popular culture is bad culture” argument. And the voices were many. (One of these days I am going to post a manuscript I banged out when living in Montreal. I called it So Logo and took issue with all the intellectuals who were then pouring scorn of popular culture one way or another.)

My confidence in the “popular culture is now culture” notion grew substantially this fall when I did research for Netflix on the “binge viewing” phenomenon. To sit down with a range of people and listen to them talk about what they were watching and how they were watching, this said very plainly that TV, once ridiculed as a “wasteland,” was maturing into story telling that was deeper, richer and more nuanced. The wasteland was flowering. The intellectuals were wrong.

2) This will change many of the rules by which we make culture. So what are the new rules?

I mean to investigate these changes and see if I can come up with a new set of rules. See yesterday’s post on how we have to rethink complexity and casting in TV if we hope to make narratives that have any hope of speaking to audiences and contributing to culture. Think of me as a medieval theologian struggling to codify new varieties of religious experience.

3) The number of people who can now participate in the making of culture has expanded extraordinarily.

This argument is I think much discussed and well understood. We even know the etiology, chiefly the democratization (or simple diffusion) of the new skills and new technology. What happens to culture and the rules and conventions of making culture when so many other people are included, active, inspired and productive? We are beginning to see. Watch for codification here too. (As always, I will take my lead for Leora Kornfeld who is doing such great work in the field of music.)

4) We must build an economy that ensures that work is rewarded with value.

I have had quite enough of gurus telling us how great it is that the internet represents a gift economy, a place where people give and take freely. Two things here. 1) The argument comes from people who are very well provided for thanks to academic or managerial appointments. 2) This argument is applied to people who are often obliged to hold one or more “day jobs” to “give freely on the internet.” Guru, please. Let’s put aside the ideological needle work, and apply ourselves to inventing an economy that honors value through the distribution of value.

I have made this sound like a solitary quest but of course there are many thousands of people working on the problem. Every creative professional is trying to figure out what he or she can do that clients think they want. I am beginning to think I can identify the ones who are rising to the occasion. They have a certain light in their eyes when you talk to them and I believe this springs from two dueling motives I know from my own professional experience, terror and excitement.

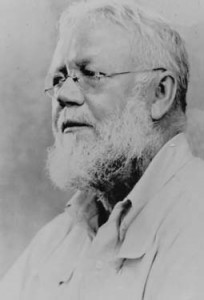

Thanks

To Russell Duncan for taking the photograph.

April 17, 2014

Two New Rules for TV story-telling (aka things to learn from Being Human)

Let’s begin here:

My Netflix research this fall tells me that the rules for making popular culture and TV are changing.

The cause? That popular culture is getting better and this means some of the old rules are now ineffectual and in some cases actually counter-productive.

Being Human is a great case study.

This is a study in fantasy and the supernatural. A ghost, a vampire and a werewolf find themselves living together and look to one another for guidance and relief.

It is a show is riddled with implausibilities. Characters skip around in time and space. They morph from one creature to another. The plot lines can get really very complicated.

And the viewer doesn’t care. (At least this viewer doesn’t.) The acting is so good that we believe in these characters and we are prepared to follow them anywhere. Even when the plot tests our credulity, we believe in the show.

The key is good acting. Without this, Being Human is just another exercise in dubiety. With it, the show holds as a story and more important it actually serves as an opportunity to ask big questions that attach to “being human.”

There is a second show in SyFy called Lost Girl. . This is billed as a supernatural crime drama. It too is stuffed with implausibility. Lots of fabled creatures and magical spells. For me, it’s pretty much unwatchable.

And the difference is largely acting. The actors on Lost Girl are not bad. They are just not good enough to deliver the emotion truth on which narratives depend, but more to the point they are not good enough to help Lost Girl survive the weight of its own implausibility.

This condition is actually complicated by the creative decision to have the characters supply the “ancient lore” that explains spells and various supernatural beastie. I found myself shouting at the TV,

“Oh, who the f*ck cares! The back story is a) not interesting, b) it does not animate the front story, c) in short, the back story is your problem, not our problem. Get on with it. Spare us the pointless exposition.”

(Yes, it’s true. I shout in point form. It’s a Powerpoint problem. I’m getting help. It’s called Keynote.)

New Rule # 1

The more implausibility contained in a narrative, the better your actors had better be.

If this means spending more time casting, spend the time casting. If this means paying your actors more, pay them more. Actors are everything. Well, after the writers. And the show runners. Um, and the audience. But you see what I mean.

And this brings us to the second new rule for story telling on TV. The old rule of TV was that actors should be ABAP (as beautiful as possible). Given the choice between someone who is heartstoppingly attractive and someone who looks, say, like one of the actors on Being Human (as above), you must, the old rule says, choose the actor who is ABAP. (The Being Human actors are attractive. They just aren’t model perfect.)

This rule created a trade off. Very beautiful actors were chosen even when they weren’t very talented as actors. Indeed, show runners were routinely trading talent away for beauty. As a result, a show began to look like a fashion runway. Even good writing could be made to feel like something out of the day-time soaps.

Bad acting is of course the death of good narrative. Wooden performances can kill great writing. But real beauty exacts a second price. There are moments when you are supposed to be paying attention to a plot point and you find yourself thinking, “Good lord, what a perfectly modeled chin!”

In a perfect world, every actress would be Nicole Kidman, perfectly beautiful, utterly talented. In the old days, when TV makers had to chose they would go for beauty even when it cost them talent. But here’s the new rule.

New Rule # 2

Do not choose beauty over talent. Beauty used to be the glue that held your audience to your show. Now that work is performed by talent. It’s not that beauty doesn’t matter. Seek attractive actors. But beauty will never matter more than talent. Make sure the talent is there, and then, and only then, can you cast for beauty. Think of this as a kind of “attractive enough” principal.

Stated baldly, this rule seems indubitable. What show-runner or casting agent would ever think otherwise? On the other hand, I dropped in on The CW recently and everyone seemed model perfect with bad consequences for the quality of the work on the screen.

A change is taking place in our culture. And over the longer term, it will provoke a changing of the guard, a veritable migration in the entertainment industry . Actors who are merely talented will have a more difficult time finding work. And, counterintuitively, actors who are blindingly attractive will have a more difficult finding work. What used to make them effective now makes them distracting.

As popular culture becomes culture, there will be many more changes. Watch this space.