Grant McCracken's Blog, page 14

May 15, 2014

TV Gets Better

May 14, 2014

New media fundamentalists, how will they react to the revolution in TV?

I read with interest remarks by Maurice Levy (pictured) on how he thinks about life after the failure of the Omnicom -Publicis merger.

I read with interest remarks by Maurice Levy (pictured) on how he thinks about life after the failure of the Omnicom -Publicis merger.

“We have a strategy, and we will accelerate that strategy. It calls for strengthening our digital operations to reach 50% of our revenue [from 40% currently], and investing in big data and accelerating the capabilities we have in integration.”

Levy knows much more about the industry and about Publicis than I ever will and I defer to his greater knowledge. But I have to say these remarks sent a chill through me.

There’s no question that the digital revolution continues and that it will change everything we know about marketing, advertising and communications.

It is also true, as I have been laboring to show the last couple of days, that there is a revolution taking place in old media as well. TV is changing at light speed. (See posts here, here, and here.)

It looks as if Levy is concentrating more on the digital revolution than the TV revolution. To be sure, this is a bias that has swept through the advertising business. A new generation came up, insisting that it was now going to be all digital advertising all the time, that the 30 second spot was done for, and that TV was now just another victim of the technological revolution. New media fundamentalists scorn old media and especially TV.

(Just to be clear, I am no old media apologist. My book Culturematic assumes new media. No culturematic is possible without new media as a means and an end.)

The trouble with new media fundamentalism is that it misses what is perhaps the single biggest story concerning popular culture in the last 10 years. Against the odds, and in the teeth of the hostility of the chattering classes, TV got better.

And this revolution means several things. That consumers as viewers are getting steadily smarter. That they are now accustomed to and expectant of a new order of story telling. I think it’s far to say that old media is still better at telling stories than new media. This is another way of saying that old media (both TV and advertising) may have been trailing new media…but that they suddenly caught up.

I know some readers are going to take this as the voice of reaction, an attempt to return the old order to former glory. So just to be clear. I’m NOT saying that old media is better than new media. What I am saying is that those who now diminish old media because of the rise and great success of new media are missing something. And just to be really clear: as cultural creatives, as content creators, whether they like it or not, new media fundamentalists can’t afford to make this error. They are after all in the business of NOT MISSING THINGS, ESPECIALLY THINGS AS BIG AS THIS. Sorry for shouting, but there is a new media orthodoxy in place and shouting is sometimes called for.

And no, this is not an argument that says advertising was perfect just the way it was. There is work to be done in the world of old media, lots of work. Remember when the ads on a show were often better than the show? These days have mostly passed. Now the ad surrounded a show looks shouty, simple minded and a little clueless. Like it doesn’t know what is going on around it. Like a revolution took place and the brand and the advertiser didn’t notice. Oh, if there is something that is NOT ALLOWED in the branding and advertising business, it’s not noticing.

So it’s not as if anyone wants us to go back to old media circa Mad Men and the 1950s. Old media must now evolute as ferociously as new media. To catch up. To keep up. That revolution on TV tells us that our culture is changing in ways no one anticipated at speeds no one thought possible. And anyone in the communications game (using old media or new media) is going to have evolve in something like real time.

Our culture is becoming a hot house. Those who want to contribute will have to flourish to do so. It makes me think of that Wieden and Kennedy moment after a recent SuperBowl. W+K had floated that Old Spice ad and as they looked at the tidal wave of online content they have provoked, they thought, “Damn. Better get on this.”

A group of them retired to a building somewhere and just started turning stuff out. Call and response. Call and response. Real time marketing.

This may be where we are headed. There are so many things in play, and they are moving at such speed, concatenating in ways we can’t anticipated, this is perhaps not the time to up your digital bet, Mr. Levy. In this very dynamic world, we want to use all our media all the time.

May 13, 2014

Are you getting better at watching TV?

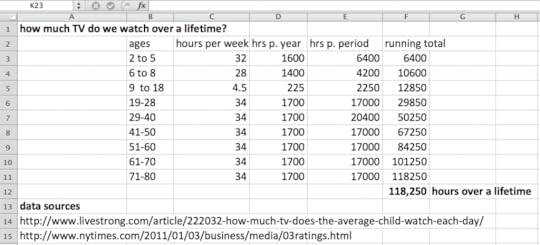

Yesterday, I suggested we’re getting better at watching TV.

This lead me to wonder: how much TV do you have to watch to get good at watching TV? And this lead to: how much TV have we watched?

If my figures are correct, we have watched around 30,000 hours by the end of our 20s. And 50,000 hours by the end of our 30s. And nearly 70,000 hours by the end of our 40s. By life’s end (assuming that’s around 80), you’ve watched over 100,000 hours. (I am discounting generational differences.)

Malcolm Gladwell says we need 10,000 hours to get good at something. We pass that figure in childhood.

But of course there is no simple relationship between watching and expertise. ”Garbage in, garbage out”, as we used to say. Bad TV is as likely to “dumb us down” as it was to confer more sophisticated taste.

But I think there is some relationship. Unless we were truly brain dead, we couldn’t help noticing how bad TV often was, how wooden the characters, how much screen-time was being devoted to that paean to stupidity, the car chase. In this case, “stupid in” gave us, in some cases, “clever out.”

How many hours did this revelation (the one that said that TV was a little thin) take? Probably more than 10,000. (And of course it would in any case. Gladwell’s figure applies to the pursuit of mastery. Lying in front of a TV does not qualify.) That would be mean we come out of childhood as witless viewers, grateful for pretty much anything that’s on.

It begins with a simple act of noticing. ”God, that was a long car chase” would qualify. Or, in the language of family vacation now applied to car chases, “how much longer!” And this is the first act of active viewing. Scrutinizing something we see on the screen. Seeing that something as a choice, a choice made by someone. Seeing the choice as something we might make differently, that we could make better.

This begins as a tiny current of consciousness, a small voice in the back of one’s mind. But eventually there is a kind of acceleration and the viewer shifts more and more from passive to active. We watch enough (and this “enough” might be 10,000 hours, which would make Gladwell’s condition the beginning, not the end of mastery) and at some point, we go “really, that’s it?” And now gradually, we begin to use our cognitive surplus, as Clay Shirky would use the term, to do other things. Now we always see the tedium of the car chase and we begin to use this “interlude” for other acts of noticing and contemplation. ”Why do we only see her left profile?” ”What is the deal with the way he says ‘immediately’?”

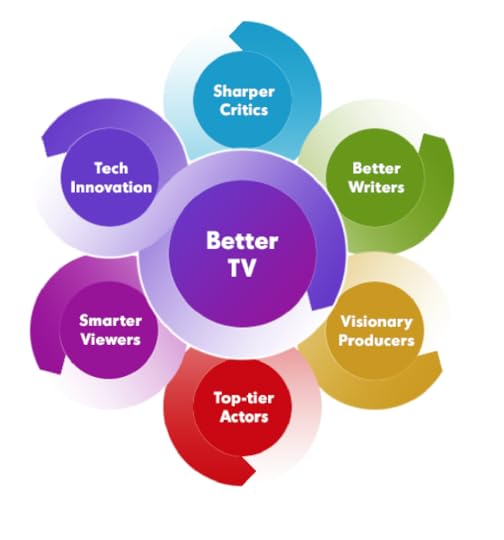

The necessary condition for better TV is in place. Viewers are paying attention. But the sufficient condition is better writers and producers. And this is another story. I think of these people as ham radio operators, desperately pouring a signal into TV land, hoping that someone somewhere will get this subtle bit of dialog. And eventually a signal returns.

Eventually, viewers and these writers find one another and a virtuous cycle is set in motion. A number of shows emerge: Hill Street Blues (1981), Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997), The Wire (2002), Arrested Development (2003). TV gets better and by the turn of the century, writers and viewers have found one another. And now the entire system changes. With better, richer TV in place, someone has probably logged the hours they need for mastery quite early on. But the end of your teens certainly.

Thoughts and comments, please.

May 12, 2014

From scarcity to abundance, the new creative surpluses on TV

Spoiler alerts for:

Spoiler alerts for:

Game of Thrones

Luther, Homeland

The Good Wife

House of Cards

Nashville, Scandal

Arrow, Teen wolf

Rest in peace:

Ned Stark (Sean Bean) on Game of Thrones

DS Riply (Warren Brown) on Luther

Nicholas Brody (Damian Lewis) on Homeland

Will (Josh Charles) on The Good Wife

Zoe (Kate Mara) on House of Cards

Peggy (Kimberly Williams-Paisley) and Lamar (Powers Boothe) on Nashville

James (Dan Bucatinsky) on Scandal

Moira (Susanna Thompson) on Arrow

Allison (Crystal Reed) on Teen Wolf

The characters of TV are falling. No one is safe. Zoe on House of Cards appeared to be a character so dear to our hearts, so embedded in the HoC narrative, she was safe from harm. This made her death on a subway platform in the first episode of the new season especially shocking.

The old convention was clear. TV was bound by a contract. Once the audience had connected to a character, once we had identified with that character, the character got a pass. Nothing bad could ever happen to them. They were safe from harm. Especially on a subway platform. Well, everywhere really.

But now that so many of these TV characters are dying, something is clearly up. Melissa Maerz of Entertainment Weekly sees dark motives. She believes that shows use these deaths as a way to goose ratings and build buzz. These deaths, she suggests, may be “gimmicks.”

Maybe. We could look at this another way. In the old TV, characters represented an investment and an achievement. In spite of its creaky, often predictable mechanics and talent shortages, TV managed to make a creature we found credible. Life was created. (Even if it did resemble the work of Dr. Frankenstein.)

In fact, writers weren’t all the good at creating new characters. And we, as viewers, weren’t all that good at grasping these characters. This was, after all, an era of creative scarcity. In this world, characters got a pass not for humane reasons, but because they were triumphs against the odds. Once we writers and viewers had conspired to cocreate a character, whew, job done, and let’s not put this miracle at risk.

But these days, show runners and writers are less like Dickensian accountants, and more like drunken lords of endless liberality. “You don’t like that character, well and good. How about this one? Want another? I’ll work something up over lunch.” The new creative potentiality on tap in TV is virtually depthless.

Why? Better writers have come to TV. All writers have more creative freedom. Every show runner is eager to take new risks. They recruit the writers who can help them do so. Actors are demanding new and juicier roles. The industry is a little less an industry and now a creative community, where the depths of talent are so extraordinary something fundamental has changed. This world (and our culture) has gone from one of scarcity to one of plenty.

And we viewers are helping. We got better too. We are smarter, more alert, better at complexity, unfazed by novelty, and apparently, so possessed of new cognitive gifts that you can throw just about anything at us and we will rise to the occasion.

We viewers may once have struggled to master the complexities of a show, and resented anyone who taxed us with new characters. Now that’s part of the fun. Throw stuff at us. We can handle it. Indeed, increasingly, we demand it. Viewers are happy to meet new characters and see what they bring to existing and emerging narratives.

Perhaps killing off characters is not a gimmick after all. This might be a way TV manages to keep itself fresh and engage the new cognitive gifts of their viewers.

This is one of the things we can expect to happen as popular culture becomes culture. TV was once the idiot brother of literature, of theater, of cinema, of the Arts. No self-respecting writer wanted to go there.

Then, quite suddenly, they did. (I think of David Milch as Writer Zero, the first man of astonishing talent to buck the trend and make the transition.) And in the 35 years since Milch made the move, many have followed. These days just about everyone is banging on the door. Even people who thought they wanted to write for Hollywood. And this takes us from that “make-do” model that prevailed on both sides of the camera. (TV did the best with what it had, and viewers made do with the best they could find.) Over 35 years, we have seen the death of good-enough TV.

As the migration of talent continues, everything changes. Creative scarcity gives way to creative abundance. Pity the shows that have yet to get the memo. And watch, ultimate spoiler alert, for more of your favorite characters to die. With our new creative surpluses, there are more where they came from. Plenty more.

May 10, 2014

Omnicom and Publicis: their kingdom for an anthropologist

We break our usual Saturday silence to bring you this astonishing quote from John Wren.

We break our usual Saturday silence to bring you this astonishing quote from John Wren.

It was issued yesterday as the head of Omnicom discussed the failure of the proposed merger with Publicis.

Apparently, the causes went beyond tax and regulatory challenges.

“We knew there would be differences in corporate cultures of Omnicom and Publicis. I know now that we underestimated the depths of these cultural differences. I want to emphasize these were differences of corporate not national culture.”

Very smart lawyers were working on the tax and regulatory issues. If only they had had an anthropologist working on the cultural ones.

Source for quote: Laurel Wentz in Ad Age, see the full coverage here.

May 9, 2014

Marketing Thuggery: a case in point

Lots of people comment on advertising only to condemn it. The Frankfurt School lives on like Frankenstein.

But I’m not one of those people. Generally, I like ads. They’re little production houses. They use some part of their culture. And they create some part of their culture. This makes them anthropologically fascinating. (Here’s a post on advertising I recently did with Bob Scarpelli.)

But today I’m pointing an accusing finger at this ad from DirecTV.

“Are my wires ugly.”

“No, buddy, no! Your wires are what make you you, little man.”

Advertising is often an act of metaphor. We find a meaning in one part of our culture and place it somewhere else. Meanings are released. Humor, sometimes, is occasioned.

Call it cultural arbitrage, as I did a couple of days ago.

So where do you think this meaning comes from? It comes from the world of disability and the conversation where the father seeks to reassure his challenged son.

You think I’m being too sensitive? Try asking a father who has had to have this conversation. Try asking a son who has suffered this anxiety.

And while you’re at it, try exercising a little cultural sophistication. It is, actually, what you do for a living.

This ad isn’t funny. It’s an act of marketing thuggery. It assigns very bad meanings to the brand. DirecTV as a brand that finds humor in disability? DirecTV as a brand that would play upon the insecurities of a child and a father haunted by both? DirecTV as a brand that ridicules a family that must confront ridicule as a matter of course?

Wow. Hats off to these marketers for this tone-perfect mastery of contemporary culture, for their virtuoso ability to find meanings and make meanings for the brand. This is marketing malpractice of the first order. This is marketing thuggery.

Acknowledgements

Normally, I would name the agency and the creatives responsible for a great ad. In this case, I will say merely that I think the offending agency is Deutsch.

May 8, 2014

Big Bang Theory Theory (you should have one)

The Big Bang Theory represents one of the big puzzles for the student of popular culture. It brings in 23 million viewers at a time when most shows would be happy to have half that number.

The Big Bang Theory represents one of the big puzzles for the student of popular culture. It brings in 23 million viewers at a time when most shows would be happy to have half that number.

Big puzzles are important. They represent anomalies so big and powerful that everyone is forced to pay attention. In this superbly fragmented intellectual moment, they give us a problem in common. Everyone should have a The Big Bang Theory (TBBT) theory (TBBTT).

The TBBT can serve as a sorting device. Searching for a question to ask a grad school candidate? This is perfect. ”Tell me why The Big Bang Theory is a success.” Either you have a good, interesting, original, powerful and nuanced answer. Or you don’t.

In a recent Entertainment Weekly, Amanda Dobbins canvassed a number of experts to construct an answer to the The Big Bang Theory puzzle. She captures several explanations.

1. Casting: great, veteran actors (Jim Parsons as Sheldon Cooper)

2. Prized Time Slot: Thursday night

3. CBS Factor: Les Moonves is a genius

4. Demographic reach of the show: loved by young and old

5. Catchphrase: “Bazinga” allows TBBT to live outside the show

6. Setting: the “French farce” advantages of the apartment house

7. Setting: extraordinary efficacy of that couch as a comic platform

8. Multi-camera format: and the intimacy it makes possible

9. Pacing: Goldilocks’ perfection: not too brisk, not too slow

(this is a partial list)

I would have liked to have seen more on Chuck Lorre. There can’t be any question that he’s a comic genius. His gifts were on full display in Two and a Half Men but that show was loathed by some for the unapologetic low-brow, frat-boy, bro-ness of its humor.

And it’s almost as if Lorre was saying, “What, you think my humor depends on pandering to the lowest common denominator of male humor? I can make anyone funny, even egg-head, anti-bros. Just watch me.” The Big Bang Theory may have been his “proof of genius” exercise. Mission accomplished.

And I wanted more on the Sheldon Cooper character. He is a deeply obnoxious human being. And Dobbins notes how effective “monsters” can be for comedic purposes. I wonder if the Parsons character doesn’t have Archie Bunker range. We laugh at him. We laugh with him. We laugh at him and with him.

This would give the character his demographic breadth. But it would also allow him to go to the heart of some of the issues, some of the contradictions, of our moment, and make them active, thinkable, graspable…not because Parson/Cooper resolves them as contradictions but because he lives them as contradictions…or we live them as viewers. This is a moment when we have seen the cultural center of gravity move from heroic males to brainy ones, from creatures of mastery to creatures who are effective and influential in spite of (and some times because of) their social disabilities and eccentricities. Sheldon Cooper may speak to some of the puzzles in our midst.

Finally, for me, and for all its virtues, the Dobbins’ treatment helps heighten the mystery. All these factors seem right, but they don’t explain the success of this show. Let’s be clear. TBBT is a semiotic, political, cultural, entertainment miracle. Mass media in the twilight of mass media. A big show with extraordinary reach in an era where virtually every other show is smaller and more narrow in its appeal. TBBT has bucked every trend, defied every tendency. Explain this and other mysteries are perhaps revealed!

What is your TBBTT?

Bibliography

Find Dobbins’ essay here.

May 7, 2014

Feminism, how far?

Over the weekend, I gave a talk at the Royal Ontario Museum, my old stomping grounds.

Over the weekend, I gave a talk at the Royal Ontario Museum, my old stomping grounds.

My task: to cover some of the changes that have happened in culture since I left the ROM in the early 80s.

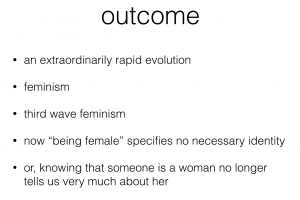

How our culture defines women, that has changed immensely. But how immensely? How far have we got. I presented the following images as a way of suggesting that we have actually stopped defining women as women.

I ended this part of my talk with this slide:

And as I ended with this conclusion, a little voice in my head said “but is this true?”

It sounds plausible. Even as it is riddled with problems.

Someone is sure to object that gender is defined by nature. They are obliged to explain how many variations there are on the “women” theme in the world.

“Exactly!” others will say. ”There is no single way of being female, but there are 12 (or 120) variations. So when you tell me someone is a woman, I can assume that she is defined by one of the 12 (120) variations. So gender still defines identity.” This might work. It might be a better argument.

But I think if we look at the trajectory, it probably fair to say that we are at least moving towards a time when knowing that someone is a woman won’t tell us very much about her.

Here are the slides with which I set up the slide above.

I started with Charlie’s Angels. Remember. These characters all came with an “identity.” One was the sexy one. One was the sporty one. One was the classy one. As if a woman had to choose. (Or viewers were so dim, you didn’t dare confuse them with anything more complicated.)

The next slide was this one: Sex and the City. This characters are still defined by a kind of character genre. (One is the sexy one. One is the classy one.) But the characters are more full blooded, more individuated.

Next up, I used this slide. When Charlie’s Angels was recast and presented as a movie, we got characters who were less defined by character (and gender) and still more individuated.

Perfect. These characters are not standing on ceremony. They are not constrained by gender expectation. They are not constrained by much of anything.

I ended with Girls. These women are wrestling with gender issues to be sure. But they are not much constrained by them. As Mary Waters says of ethnicity in America: it’s a matter of choice, not biology, history or community. These women have chosen who they are. And they are largely and increasingly free to choose who they are.

And today we end with a new feature. A poll to see what you think. Please vote!

Take Our Poll

May 6, 2014

Are you an Orderist? (Take the test and see!)

Everyone in the creative professions lives or dies by their ability to detect change, see new patterns, invent new things.

Everyone in the creative professions lives or dies by their ability to detect change, see new patterns, invent new things.

And in a world like this, I think it’s possible we are developing new cognitive abilities in a rapid cultural evolution.

There are several new cognitive styles in the works. But beneath them all is, I think, a brute feeling for order. Whatever we do for a living, we are more interested in order as order.

Are you one of these people? Take this test and see!

I want you to answer four questions. Be honest. No cheating.

Question 1: Do you like order more than most people?

You will know this to be true if (and only if) you are captivated by certain combinations of numbers, images, sounds, words, shapes and colors while the rest of the world just carries on.

Do you take pleasure when the world “falls into place,” when “things make sense?” Some people experience a little buzz as if they have just been given a hit of a psychoactive drug. The nervous system hums for a moment. It feels like something has been illuminated, even when we can’t quite say what.

Question 2: Do you dislike disorder more than most people?

Do you find that commotion bugs you more than it does other people? It might just be a scratching sound or a piece of furniture that’s out of place. I’m not suggesting you want perfect symmetry or military precision. I don’t mean an obsessive or compulsive interest in order. You just don’t like noise in the signal.

If you answered “yes” to questions 1 and 2, congratulations, you qualify for membership in an emerging community of people who care about order for its own sake. Chances are you’re someone who makes his or her living engaging in the part of the economy that creates ideas and innovation. So it makes sense that you should care about orderly order. But it’s more than that. You care about order for the sake of order. For you, order isn’t just a means. It feels like an end in itself.

Some want to put this community on the autistic continuum and call you “Aspie” (aka someone with Asperger’s syndrome. See the excellent essay by Benjamin Wallace called “Are You On It?” in New York Magazine here). Others want to say your passion for order identifies you as having an Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. To be sure, it is entirely possible that there is one or more neurological factors at work here. But I don’t think that’s the whole story. I think it’s possible we are cultivating new cognitive styles and preferences. Some of us are orderists. Some of us have orderism.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. I have two more questions.

Question 3: Do you dislike order more than most people?

I know this sounds like I’m contradicting Question 1. But I’m not. I am granting that you like some kinds of order more than most people, but I am suggesting that there are certain kinds of order that really get on your nerves. As when things are too tidy, too neat, too perfect. You hate this order with a passion.

Other people couldn’t care less. They can “live with it.” But what you see is a world that’s too tidy. The pattern is too obvious. There’s no contest. It’s like watching genre TV. You can see the punch line coming. And it gets to you. You would like to just nudge this order ever so slightly, to put a little disorder in. Naturally, you don’t. Because, well, you don’t want to look like a kook. But tidy is often just too too.

Question 4: Do you like disorder more than most people?

Once again, no contradiction is intended because we are granting that you dislike most disorder. We are merely suggesting that there are certain kinds or moments of disorder you really like. Love, actually.

Again, this puts you out of step with the rest of the world. Let’s say something nutty happens. Everything comes pouring off a shelf. There is a moment of pandemonium at the office. The rest of the world is offended, perturbed, upset. You are thrilled. You are energized. Perhaps even liberated. You like it when the world is released from the rules.

Answer “yes” to all four and you are part of a new elite. You are part of a community that loves working with order, sometimes because it is so very orderly, sometimes because it is so very disorderly. Some people like Late Night Television. Some people like fishing. You like working with order. These “symptoms” aren’t signs of some physiological or mental disorder. You’re not an Aspie. You do not have OCD. You’re just engaging in a new kind of pattern seeking.

And here’s why.

Order is harder to come by. The world is filled with variety and commotion. If once we were a monolithic culture, we are now a heterogeneous one. We produce variety effortlessly. There are more groups, working in more media, from more and more various motives and objectives out there. And together, they make our culture a place of astounding variety. Don’t believe. Try having one conversation with your 15 year old that does not contain a long silence as you try to figure out what she means. Or drive around downtown and see if you can go more than 15 minutes before thinking, “what the hell is that.” Or just spend some time wandering around online. Or look at what is happening in the startup space. The world is boiling with variety.

And that means every organization lives in a wind tunnel. Every given moment is complicated and various. And any given moment is almost instantaneously replaced by a succession of moments that deliver still more variety. Things move so quickly Nokia missed a major shift. They move so fast Michael Raynor says strategy is dead. They change so fast a new challenger or challenge can come from anywhere.

This means there is a new premium on early detection, figuring out what’s out there in the world and how to respond to it. Our managerial window, always pretty broad, is now expanding as we peer around us looking for blue oceans and black swans. For organizations to survive, new abilities are called for. Early detection is everything. Advantage will go to people with a ferocious feeling even for the slightest traces of order.

That’s why you are interested in order for its own sake because this is the surest way of capturing order for instrumental purposes. We can’t tell what we need to notice. We just need to notice everything. An interest in every kind of order gives us first recognizance, first contact, first reckoning. At this point, we are not particular. Any order is better than no order. Even trace elements of order are interesting also because we are virtuosee, capable of working with the faintest signals.

So if you are order interested, order observant, even a little order obsessive, consider yourself lucky. You are cultivating an ability everyone is going to have to have to survive the world thats coming at us. And perhaps this is the place to say, let’s perhaps cease and desist on our Aspie obsession. Yes, there may very well be some neurological or physiological factor here. But while we are all claiming Aspieness, trying to stuff ourselves into a DSM category, we are missing the bigger picture, dare I say it, the bigger pattern.

Time to stop treating our interest in order like it’s a symptom of Asperger’s or Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, and see it for what it is. We are a society evolving at a ferocious pace and some of us have begun to adapt accordingly. It’s not about brain wiring. Its about how we see order, use order, order order. The world is changing. We’re adapting.

Thanks for the image to nicklilavois. See his website here.

Thanks to Pam DeCesare, my wife, for thinking of the term “orderist.”

May 5, 2014

Bosco 3.0: ethnography and design to the rescue

I’ve been thinking some more about Bosco, the kid who knows all about meth labs and not a lot else.

It’s a problem that demands anthropology, ethnography, design thinking, strategy, marketing, several of the intellectual practices we now have on tap. (See the preliminary posts here and here.)

One approach: transfer the knowledge possessed by kids of privilege. So that Bosco does not suffer that pernicious disadvantage of constrained horizons or what we might call a “cosmopolitan gap.”

There’s an inclination to say, “Perfect! It’s a simple transfer. We find out what Tommy (child of privilege) knows and send this knowledge to Bosco.”

But of course it’s not this simple. Knowledge is not data organized according to a single scheme. It is not something that exists independent of communities and practices of knowledge.

But of course it’s not this simple. Knowledge is not data organized according to a single scheme. It is not something that exists independent of communities and practices of knowledge.

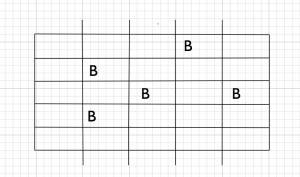

So it’s not the case that Bosco’s knowledge of the world looks like this:

And Tommy’s richer knowledge of the world looks like this:

And what we need to do is to communicate Tommy knowledge of Bosco.

Instead, knowledge is variously assembled and framed so that what is knowledge in one system may not show as knowledge in another system. Or knowledge in one system may show in another, but it takes on a new place or significance. This is an elaborate way of saying we don’t just need to know what Tommy knows but what Bosco knows. And then we have to build a translation table. Not a Rosetta stone, but something more complicated and calculating. Less a translation table, more a translation machine.

Notice that we are not taking the postmodernist bait and sliding into that sophomoric relativism that says Tommy and Bosco live in worlds so different that communication or transfer is impossible. This is good fun to debate in a university seminar. But when it used to frustrate our rescue mission, specious nonsense turns dangerous too.

Off the bat, I can see two ways that cultural creatives can help.

architecture of knowledge

This is what ethnography is for, after all. We can sit down, and capture the categories of Bosco’s knowledge, how these go together, what assumptions they rely on. We can build a rough model of the inside of Bosco’s head. And with this we can begin to figure out when, whether and how to begin the transfer of knowledge from Tommy to Bosco. We noted in previous post that this transfer will have real implications for Bosco’s relationships with friends and family, but that’s not the problem we are solving here. Our task is to discover what Bosco knows and the way he thinks and to use this to prepare the way for a transfer of knowledge.

visualization of knowledge

This is the really interesting part. And now I am at the edge of my competence. The idea here is to represent Bosco’s existing knowledge and to help Bosco see how new knowledge attaches. Because as we know knowledge is adhesive. This is why it’s easier to get knowledge if you have knowledge. And of course knowledge is also hierarchical. It’s hard to learn some things if you don’t already know other more general things.

This is a job for the designer, to create a visualization of what Bosco knows and to use that to introduce him to new knowledge and show how he can “attach” it to existing knowledge. Where necessary we will build some intermediating pieces of knowledge, so that Bosco can learn something for which his existing system of knowledge does not yet have points for adhesion. (Or we hold back knowledge until other knowledge is in place.)

Effectively, the cultural creatives will occupy a lab that might as well be called “the inside of Bosco’s head.” We will know what he knows, what he is ready to learn, and what he has to learn to learn something new. We will constantly be working on a grand visualization that helps Bosco assimilate new and useful Tommy knowledge.

These are thoughts only. Your comments, please!