C.J. Martin's Blog, page 8

July 9, 2015

matlaporte:

To start indicate the place that’s nine-tenths. Smallin volume, it lies suspended in...

To start indicate the place that’s nine-tenths. Small

in volume, it lies suspended in our body. A child

visualizes a sphere floating through hollow arms and legs,

dancing through the torso. It contains the rest, but

is finite. It appears to be an insignificant point,

free in itself, permitting misconception, perfection

belongs behind you and in what you will do, just as

in time there is never a nine-tenths. Only its

endless picture.

- from “Nine Tenths Of Our Body,” by Diane Ward, in Code of Signals

July 5, 2015

Now living with us, courtesy of eBay: Kitaj’s portrait of John...

Now living with us, courtesy of eBay: Kitaj’s portrait of John Wieners, from ‘69. Part of this series of screen prints: http://www.broadbentgallery.com/wp-content/files_mf/kitajonlinecatalogue.pdf

July 2, 2015

furtherotherbookworks:

Head over to Jacket2 and check out Rob...

Head over to Jacket2 and check out Rob Stanton’s review of Sarah Campbell’s WE USED TO BE GENERALS! (Then get your copy here.)

June 22, 2015

June 19, 2015

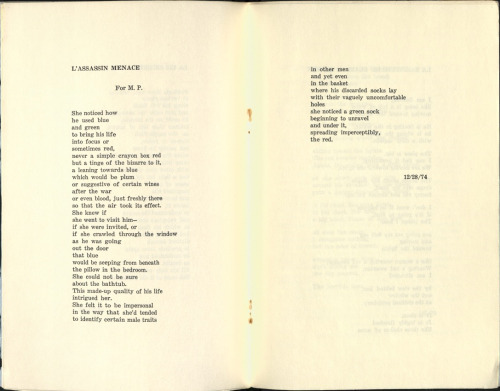

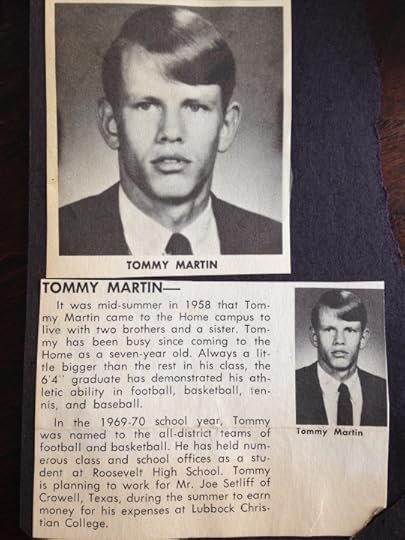

No Relation (III & IV)

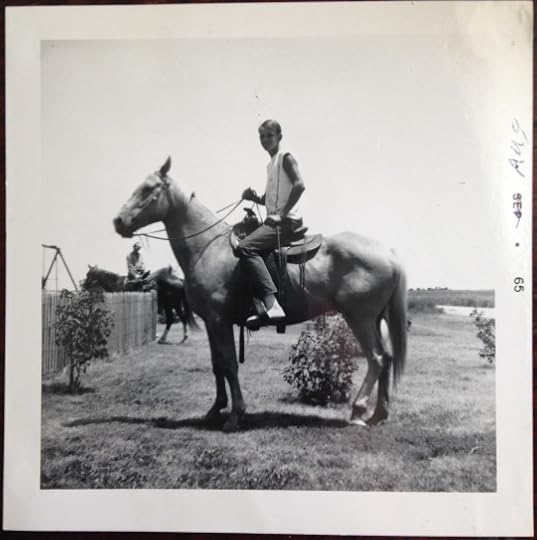

In the lead up to father’s day, I’ll be serially posting this essay on relation and the coincident, which is also a meditation on my father and Robert Creeley. The following is the last two sections, but the third section’s incomplete, so this is a working draft. (Need to treat Hawkins’ Back to Texas more directly, & would welcome interlocutors, if anyone would like to comment/read.) Pictured above: my father’s graduation announcement from the Lubbock children’s home.

III.

“The poem is a capsule where we wrap up our punishable secrets.”—The Autobiography of William Carlos Williams, p. 343

In “Inside Out,” Creeley frames Williams’ oft-cited claim about “punishable secrets” (from a passage, it bears noting, on visits with Pound at St. Elizabeths) as a Puritanical approach to autobiography. Creeley notes the “clear signs of a kind of paranoia in this mode, just that the I feels itself surrounded by a they to which its experience of itself cannot easily refer” (CE 562). Creeley’s punishable secret: that, at the time, he shared this paranoia. (Maybe not so secret, certainly not the only thing punishable.)

The formulation always strikes me as a lie or a seduction—an effort to sex up the work of doing poetry—so it’s funny that Creeley calls it Puritan (funny, too, because if WCW and RC were standing side by side, I’d likely point that finger at the latter, if forced to choose). More to the point, to write a poem and to call it work, to tuck away some sin and then hustle to sell it off to a readership, would seem to require a pretty deep well of weirdness to maintain the public interest, if that’s your model—but the truth is that so many truly punishable secrets aren’t, at least in the absence of a high public profile, so readily forgiven, even in poetry. A good hustler includes the juicy bits, but not the real transgressions.

Alternate take: Kyle phones to say Creeley was writing mileage and maintenance logs—who did what & where they did it, etc. I like it, but the more I sit with it, I start to think it’s too metaphoric, still—like the horse poetics. Most types of what I’ll call real work you can’t apply for a money prize to afford you time to do the work in the first place.

“Inside Out” was completed in Buffalo on March 22, 1973—my father’s twenty-first (false) birthday. He only found out late in life that he’d actually been born the day before. He’d taken a job hot-shotting (hauling small loads, not large freight exactly), which led to an offer to drive truck for 7-11 on a promotional tour to the east coast, passing out free t-shirts and Slurpees at special events or whatever. The drive would take him, presumably, across the border into Canada, so he’d have to get a passport, and the passport folks told him they’d need his birth certificate, which he’d never had. When he went to get it, he discovered he’d been celebrating the wrong birthday all his life, and as a consequence, had to get his license changed, too.

I’m not sure whether it was that the people who ran the children’s home relied on the kids to fill out the paperwork (who were very close to right, if that’s what happened), or whether they simply couldn’t keep the birthdays straight among the 20 or so kids who lived with each family. Either way, the news really wrecked my dad—one more joke at his expense, from beyond the grave. But he loved the trip so much he brought us all free 7-11 shirts. A friend of my mom’s wore hers to the funeral.

“I figure the most evident problem with this separation, or what to call it, will be boredom, and the restlessness that comes of it,” Creeley writes to Bobbie Louise Hawkins from Buffalo, January ’73, after a kind of nostalgic road trip across country. He’d just moved back to New York again: Hawkins had initially remained in Bolinas, and Creeley made a point to drive through New Mexico, down memory lane as it were, passing through Albuquerque and environs where they’d lived in the ‘50’s and ‘60’s, to get to Buffalo.

The letter’s longish, about settling in, unpacking, etc.—about the trip there, pollution, the weather (taking the temperature re this time apart):

Apparently local Buffalo paper had pictures of Bolinas’ flooding, house falling down hill (?)—sounds like a wild time. I hope that creek kept the waters moving off our so-called property. Albuquerque, by the way, now has smog all through the valley […] The whole city felt jumped into ultimate Princess Jean Park vision of ‘success’—later saw “The Brave Cowboy” on late-night TV, appropriately enough. Texas was COLD … panhandle frozen stiff, but in garage where I went to get push for frozen car by that point (morning), lovely conversations going on with ‘good ole boys’ and ‘waal’ and what you’d expect. Last thoughts of Albuquerque: local Buffalo radio/tv report of commissions’ recommendation that LA would have to cut down on gasoline consumption […] —reaction is, apparently, to lower the standards qualifying smog […] Too fucking much. Like the farmer’s horse living on less and less till one day he just died. What a weird imagination of success!

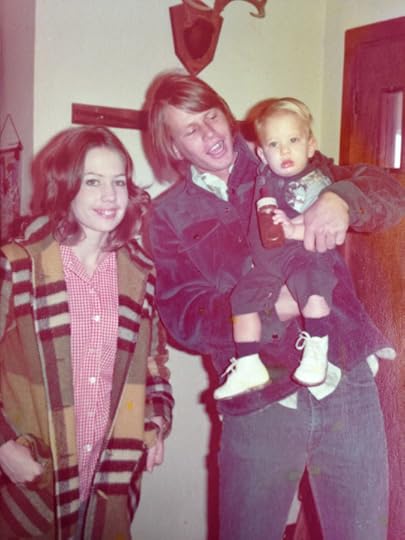

Shortly after Creeley’s trek through the panhandle, my parents met for the first time at an apartment complex in Odessa. There are two stories about how:

One version has it (and this one I grew up with) that my great grandmother, wife of a Baptist preacher, warned my mother off of the skeezy looking guy with the long hair while helping her move into her new apartment complex, and that later my dad showed up at my mom’s door in a towel to borrow soap or something. In this one, dad’s a bad seed, which fits with some of what I know about them both at that age: she frequented a rock club called The Shadows, and he was a roughneck, for one. He had a fiery temper, liked to cut loose by hustling pool, drinking, and fighting; one of his best friends was named Tom Goodnight (a super sweet biker who once let us pick up beer cans from his property for a school recycling fundraiser—mountains of cans, like an alcoholic junkyard). Dad has a black eye in my parents’ wedding photos from a bar fight the night before.

The other version I only learned recently, during my mother’s recovery from the injuries she sustained in the tornado, which resembled, one rad-tech said, a biker who slams head-on into a brick wall. A couple of weeks after the storm, my mother told a very different version to Julia of how she and my dad met, and then told me. In this one, she was out on a date. The guy driving took what she thought was a wrong turn, and when she said so, he told her that they’d go wherever it was only after she put out, that otherwise she’d be walking home. She chose to walk, a few miles or something (luckily it was really an option), and when she got there she realized she’d left her purse in the guy’s car and didn’t have her keys. So, she knocked on the door of the apartment where my dad and my uncle Gary lived and asked if she could use the phone. Only after calling whomever for her spare did she register that she’d just traded one threat for another, but she waited with them, got to talking, and she and dad hit it off. My understanding is she never told my dad exactly what brought her to his doorstep.

IV: Two Codas

“Hold on, dear house […] You are my mind / made particular” — from “This House” (Echoes)

When my parents moved Julia and me to Buffalo in the summer of ’05, my dad and I fought like we hadn’t done since my teens. He was pissed; I was impatient. There’s no room for his F-250 on the one side of Linwood Ave. that allows parking. And the parkable side of our new block changes depending on the day of the week or something, so this became a big issue for him—proof I’d chosen against him I think (moving across country for a Ph.D., settling in a ‘big city’). I maybe had, but I didn’t think that’s what I’d been doing.

Once I’d asked if he wanted me to bring anything back for him from the east coast. His response was casual, but compulsively forthright: “I never lost nothing in New York.”

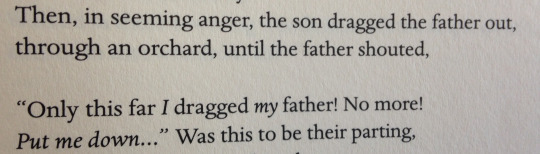

And now I think of Creeley’s repurposed folk tale of the impudent son who attempts to kick his father off his land (was never sure whether he got it from Stein or elsewhere, who uses it to open The Making of Americans):

(“For Will,” from If I Were Writing This)

Stein adds that “It is hard living down the tempers we are born with.”

… And I think maybe that’s what I’d done after all, dragged him across country to drag him out, period—my house as my mind made particular.

Whereas my dad aged out of a children’s home and moved to Odessa to be closer to the father who’d left him there. Upon arrival in 1970, he went to work on a rig for my uncle James. I remember James by his metallic green Cadillac, my Aunt Barb’s gold-sequined cigarette case. He has dementia now*, but just before the tornado he and my dad met again after I don’t know how many years. When they spoke of the oil field, James was completely lucid.

Julia and I stayed in Buffalo for less than a year before I quit Ph.D. work, then back to Texas.

Journal entry, 2-28-14

First birthday without my father is a different kind of birth. A renewed grief when I woke up that I couldn’t pin down until my mother called to wish me happy birthday & it dawned on me that it was now a half wish, a clipped conversation in the absence of his voice chiming in.

A birth to grief a few months shy of his one-year death day. I try to remember his voice, to put the words in his mouth (in my head) & best I can do is an association: at the end of Johnny Cash’s “Oney” the spoken part always reminds me of my dad, of something he’d say, so in lieu of imagining him wishing me a happy birthday, because I can’t get the sound of his voice around those words in my mind, I listen to him laugh and repeat: “Hey Oney! Own-ie!” The lyrics are the employee’s threat whose first act upon retiring is to find his boss (Oney) and beat the shit out of him. I hear him laugh and repeat the threat, letting his pitch climb on the last “Own-”—even see him kind of cock his head, a little amused at the song, at the threat.

1/8/14-3/18/15

* James died in July 2014, while I was drafting this essay.

Angela Davis

June 15, 2015

No Relation (Part II)

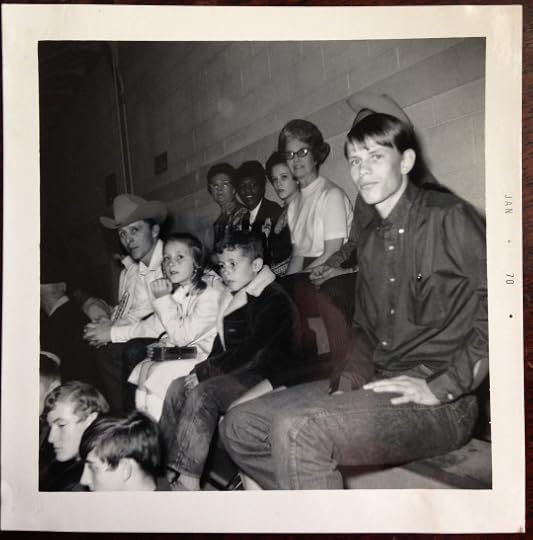

In the lead up to father’s day, I’ll be serially posting this essay on relation and the coincident, which is also a meditation on my father and Robert Creeley. Pictured above, my father in the foreground, sitting with his clothing sponsors, 1970. (Not quite a foster family, but the children’s home he grew up in enlisted the help of the community to provide clothing and time away from the home; Lewis and Sandra Light were very dear to him throughout his entire life.)

II.

“There isn’t a hippie in the world that doesn’t want to be a cowboy.” –Bobbie Louise Hawkins, Back to Texas (111)

Creeley’s thoughts on the Western are shot through with romance, so it isn’t a surprise that the editors of this recent volume of letters would follow suit. In the 1982 essay “My New Mexico,” for example, he writes that, “If this is the Wild West of Geronimo and Billy the Kid, it’s also that of White Sands and the first atomic tests—equally brutal and ahuman. Because there is so much outside, such a vast, extraneous skin, such a plethora of virtually useless space, one hands it over to whatever can inhabit it, missile ranges, uranium mines, anything to take it away” (CE 444). (What would New Mexico have looked like if ‘one’ really had handed it over?)

Or, per riding off into the sunset, see the 1983 “Cowboys and Indians” essay, where Creeley tells a story of riding horseback with Bill Eastlake—near Cuba, NM in the summer of 1960—and “threading through the oak brush, meeting with Indians trailing horses, spotting the occasional old-time homesteader who might well have got there before the territory had become the present New Mexico (1912?)” (CE 321-22). (Cuba is located at the southern tip of the Jicarilla Apache Reservation, formed in 1887 and expanded to its current extent in 1907.)

And Creeley’s dependence on the figure of the horse in his own poetics is often really hilarious:

I know that attention to what has been written, what is being written, is a dearly rewarding experience. Nonetheless, it is not the primary fact. Far closer would be having a horse, say, however nebulous or lumpy, and, seeing other people with horses, using their occasion with said horses as some instance of the possibility involved. In short, I would never buy a horse or write a poem simply that others had done so—although I would go swimming on those terms or eat snails. Stuck with the horse, or blessed with it, I have to work out that relation as best I can.

(“Was That a Real Poem or Did You Just Make It Up Yourself?” CE 574)

It strikes me as funny because in one way the horse is part of Creeley’s machismo. He’s not horse people—bird people, sure, at least early on, but mostly he’s poetry people. Cowboy must be some of the most ubiquitous American drag (for ‘real’ cowboys, too). Black Mountain men share with roughnecks (and Kid Rock) this will to offer a heroic western narrative in response to the question, “How’s work?”

My mother tells a story, from when she first met my father, of going to pick him up and him sliding down a guy wire from the top of a rig to greet her at her car on the ground below. At my grandmother’s 80th birthday, my dad and my uncles reminisced about the oil field in the ’70’s, and in their telling, the rig itself did everything but neigh—they rode it high (some literally high), they rode it low. Gunslingers and rattlesnakes made the occasional cameo.

And yet there are real horses and sometimes poets and roughnecks really do meet them. The problem of that encounter is maybe the most apt illustration of how I understand relation, as a dilemma.

My father had a conversation with animals he never had with any human person.

When my brother and I were still kids, dad would sometimes bring home a rattlesnake from the rig in an empty oil drum and keep it in the garage. In his truck he kept a long pole with a wire noose through it in case he came across a snake, but instead of killing them, they became object lessons to impress upon my brother and me the sound they made, how they responded to being confronted by people. He seemed to thoroughly identify with them.

Once, just before I graduated high school, he asked if I’d keep him company on a drive out to a drill site a couple of hours away, in the direction of Marfa. Our talk turned at one point to his reasons for staying in the oil field, and in romantic but economical terms he offered only two: the landscape, the mountain lions.

After the tornado, I’d learn from my mother of the time, midday on some oil field road, when he came upon an enormous hog loose from a nearby farm. The hog stepped right in front of his truck and wouldn’t budge, so dad got out and waited who knows how long, transfixed, until someone came to claim it. According to him, it stood chest-high (he was six feet tall).

Confronting the animal might work as a metaphor for relation in the ‘place’ of address: the audience might as well be mute, for one, but is also somehow indecipherable, requires some kind of nonlinguistic care-as-communication, forcing one to isolate relation itself, to tune out the fuzz and get right down to it, in all its inscrutability.

Creeley published “The Creative” in ’73 (as Sparrow 6), which includes an essay and a poem for his mother, who’d passed in October of the previous year. The essay is mostly really wild, eventually less so—it’s his working-through of the phenomenological problem of creativity. Lots of veering, even through gnosis: at one point he offers the notion of the himma, whereby “the gnostic creates something which exists outside the seat of his faculty,” as a recuperable understanding of what he means by the creative. He cites the following as an instance of this kind of act:

I knew a man once who had a lovely team of horses, this was in West Acton, Mass., and one of them kneeled on a nail was in the planking of the stall, and the knee got infected—Mr. Green* was his name—and Mr. Green, who lived alone with his wife, both about in their seventies, he used to, literally, take the blankets off their bed, this was in winter, and go out into the stall and wrap up that horse and put poultices on her knee, to draw out the poison, and he’d sit there with her, all the night, and finally the old horse, old in its own way as him, got well.

(CE 546-547)

The story illustrates relation, maybe more than himma, as far as I understand it, though I like the idea that care is something that can live externally, something with its own vital force. I like the suggestion that care might be a creative act.

After the tornado, I asked my dad’s older sister to tell me about their life growing up in a children’s home in Lubbock. He never talked about it much, and the only stories he’d told when he was alive had been bleak, about abuse and abandonment, teachers who used 1x2’s on the backs of the heads of mouthy students, ditches dug for no reason and refilled as punishment. My aunt described the time, not long after they’d been left at the home, when my dad, his older brother and two friends plotted to run away. They had responsibilities on the farm attached to the home, though, and it was decided between them that someone would have to stay behind to care for a pig who’d taken sick. They drew straws, and my father stayed. The cops caught everyone else not far from the home, and they were brought back and punished.

That someone was tasked with this care, despite the at-that-point-dire need for escape, and that it precluded escape. The givenness of that relation, in the face of the utter failure of the familial one. It’s Creeley’s phrase, but my father seems from a young age to have had more in common with any animal than with those animals, “the so-called people.”

In Creeley’s talk of ‘the people,’ the distance isn’t easy—much like the distance between himself and Bobbie Louise Hawkins that he traces in “Away.” The people seem to stand at odds with his attempt to locate a place where, in relation to Hawkins, that distance could be bridged, and yet he seeks the people out as part of his vocation. Given the dedication to Hawkins, this poem might read as a love letter, but I love how quickly complicated it gets that there’s an audience—and that she’s in it, somehow, out there, with them—that the poem was published in a book, that he read it at least once for a crowd (at Goddard College, May 18, 1973).** The poem could be rededicated, “For Bobbie & the so-called people.”

He was in Michigan when he completed “Away,” and she in Bolinas—likely freed up to write in his absence, who essentially forbade it.*** The poem comes out of a marriage that was falling apart. The Black Sparrow collection, Away, which contains art by Hawkins throughout, came out right around the time when the couple finally split.

About 30 minutes into the Goddard reading, a disturbance erupts that stages exactly this drama of “I don’t want to talk to the people where the heart is.”**** It’s not a brawl or anything, but a guy in the audience starts heckling—his complaints are almost inaudible, so you really only hear Creeley’s side of the conversation, but it’s enough to derail the reading for awhile. Someone attempts to redirect Creeley by asking that he read the poem about his mother’s death, and he barks back that he’s not going to read that poem.*****

Somewhere in the volatility of this poorly recorded exchange is something that stops me, something I’ve listened to over and over again since. Call it a problem I recognize:

The situation when whatever one makes has become so inextricable from how one understands/processes/engages one’s own experience that writing the experience (of grief, say) becomes not a performance but the real event. So that saying it aloud to some people just literalizes that thing where the artist lives/sleeps/etc. in the installation, for an audience—what I’m trying to name is more like giving the so-called people the keys to the house and letting them watch you cry yourself to sleep, cry yourself awake. Making and experiencing having grown together somehow. The reality of the poem or of writing is thus very close to the reality of the dream—maybe not the real event but, while you’re in it, goddamn real enough.

This essay was derailed for a time by my compulsion to dwell on/in paranoia: my own paranoia in this public display of griefs; the wrenching feeling of reading “LAND” to an audience, recognizable somehow in Creeley’s ’73 reading; my paranoia even before the storm—writing an essay on Helen Adam and the bomb, and writing super irate, super paranoid poems. Derailed by revising my memory of the time just before the storm, in the wake of it—reading back on that time, in my grief, some kind of prescience.

Julia points to the problem’s relation to hysteria, its operating in excess of some inside/outside line—so: the paranoid social = no boundaries. “I’m telling you a story to let myself think about it.” (I.e. because I can’t think it any other way than by telling you, and fuck you for that.) I wish I could say the feeling has since abated.

Vocal or not, grief has an audience at every turn: during the first funeral reception, representatives from Billy Graham’s organization interrupted the meal to donate two copies of The Billy Graham Study Bible to our families, even though (they made a point to note) my dad wasn’t devout like my grandmother. During the funeral procession—which was observed by seemingly everyone in Granbury, who parked their cars and stood beside them—my aunt posted streaming FaceBook updates from the motorcade itself and the service after, so that my mother could watch from her hospital bed. During the clean up after the storm, we met scores of volunteers and lookie-lou’s, and every once in awhile someone would directly request the blow-by-blow. Even months after the event, while I was (reluctantly) touring a firearms manufacturer in Granbury, my brother and I were prompted by our guide to rehearse the details for a bevy of white dudes (some swastika’ed, some simply bearded) who worked the production line.

In such a public performance, we trained ourselves not to disappoint, I think, or else we just crawled in somewhere, and I can’t speak for my brother or my mother, but my sense was that most every time I found myself in the situation of being expected to report that trauma to some stranger, my distance from ‘them’ grew. And I read that expectation into almost every encounter, which can’t have been the case.

Not long after the tornado, we noticed that someone had taken some tools from the house. (No one could stay there, so it was basically left unattended at night.) I called a local mover and asked for some emergency help, and the next day they sent a few volunteer crews to pack the house and move it to a storage unit.

At some point during the move, I was helping my uncle sort through some of what remained of my grandparents’ belongings, and I came upon something that moved me immediately to tears. When he attempted to hug me, I noticed some of the movers could see us and I pushed him away. Can’t change that response.

Towards the end of the day, I found myself in the kitchen talking to a couple of the movers, who were expressing shock at just how much damage the storm had done, and before I knew it I’d launched into the entire narrative. Eventually I realized the audience had grown and there were 15 or 20 men standing there listening, and I could feel myself walk out on my own story to observe the staging of it, a little repulsed and afraid I’d auctioned off my own grief.

For me, Away begs the question of what attention is to begin with. Why do we attend? What compels us? And here, I mean to consider the writing/art itself as an attention (to the world), in addition to the book having an audience listening in.

I won’t claim to be able to read Away without getting somehow wrapped up in what I know of the lives going on behind it, without somehow ‘enjoying’ that drama (is there any other way to say it?). Which makes me sure that the fear about ‘the people’ must have been so much more palpable in situ. I think of Creeley’s paranoia as the result of being a writer of the domestic on the eve of the domestic’s implosion, both personally and culturally.

I don’t want to talk to the people where the heart is…

But isn’t that what we do precisely there? Aren’t the so-called people always part of how we construct relation, even at home? Don’t we relate out of what we know from the various attentions we’ve paid? I just can’t shake the sense that Creeley’s personal turmoil during this time was somehow wrapped up in his finding certain of the people’s demands (i.e. second-wave feminism) so untenable, his refusal to ‘talk to the people’ at home. Like saying, I want discourse checked at the door…

According to Bobbie Louise Hawkins, “When Bob and I were first together, he had three things he would say. One of them was, ‘I’ll never live in a house with a woman who writes.’ One of them was, ‘Everybody’s wife wants to be a writer.’ And one of them was, ‘If you had been going to be a writer, you would have been one by now.’” (Fifteen Poems, belladonna* 2012, p. 32).

Elsewhere, Creeley in an interview on being raised by women:

“Also, growing up with five women in the house, man, I knew all the signs and gestures and contents, or at least I knew a lot of them that were manifest in women’s conduct. Ways of saying things, ways of reacting, making the world daily. But I didn’t have a clue as to what men did, except literally I was a man. It’s like growing up in the forest attended by wolves or something. It took me a curiously long time to come into man’s estate.” (MacAdams interview from ’73, p. 81).

From MacAdams’ introduction to that interview:

“After breakfast Creeley and I went upstairs to his study, a big sunny room looking out across a long wooded valley to Lake Erie. The study had once been a nursery and the framed photographs of Charles Olson and John Wieners, and Bobbie were set off by a pink wallpaper covered with tiny horses and maids.” (72)

Should I tell you the dream about Puerto Rico and the pink Cadillac? Email to Jean Donnelly (1-31-14) on some difficulties of returning to first teachers:

“I hear you re the return: I’ve been really into the ’50’s lately in poetry and letters (set off by nostalgia for some of those first loves and by apocalyptic thinking?), but it’s such a twisted time. It makes sense to me right now to write about Creeley and my dad together because I have roughly the same feeling for RC—like I feel like I learned so much from him but he very often embarrasses me with his having been so slow to get in touch with more than that circle of maleness. I dreamt about my dad last night and we’d traveled to Puerto Rico or something. At some point we spoke to some barkeep and my dad made this face to me about how effeminate the guy was—then I turned around and dad was lifting the body of a pink Cadillac! When I woke I laughed my ass off, cause it seems like gender’s always that kind of awkward demonstration. To read Creeley’s early letters to Olson it gets so thick—what we’ll MAKE Corman do with Origin etc. Seems so far from where I entered his work—can’t say I’d have kept going if I’d begun there.”

…But I think maybe I can’t not have begun there. It may not be such an uncommon shock, that realization of historical blindness on the part of someone whose thinking one otherwise trusts, but what really smarts (for me) isn’t the sense that this lack of foresight, this lack of insight, is somewhere hard-wired into my own thinking given I put myself to school there, but further, that I fucking chose it. The fact of having had to make a concerted effort to unlearn misogyny only followed the condition of having chosen, however casually or naively, to love it in the first place.

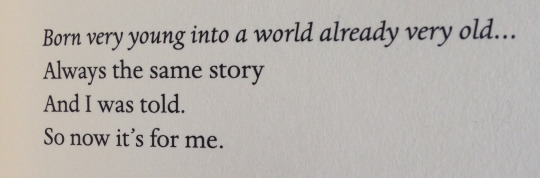

Creeley, “‘Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang…’” (If I Were Writing This, 31).

It’s from a poem written much later in life. When he reads it aloud, there’s the (to me) heartbreaking emphasis: and I was told…

Even in hindsight, no getting off that hook.

Notes:

* John Wieners, in a 1973 interview with Charley Shively, says that Creeley visited him in 1966 and introduced himself to the woman Wieners lived with at the time as “Robert Greene.” (John Wieners, Selected Poems: 1958-1984, Black Sparrow Press, 1998; p. 297.)

** Per the Goddard audio, the poem was completed in Grand Valley, MI on 7/11/71. Creeley notes in that reading that this is “an old Ted Berrigan poem.” At the time of the reading (’73) the poem retained the phrase, “going home,” as its final wording, which phrase is dropped from the published version by ’76.

*** See Fifteen Poems interview. She would have been working on the poems in that book, as well as the brilliant prose of Back to Texas.

**** Email from Bob Grenier, 3-20-14: “I must have been there, probably wd have brought Creeley over to Goddard from Franconia (where I was teaching at the time, where RC wd have just read & stayed), but I don’t remember anything abt it (there was a sort of little ‘North Country Circuit’, back & forth, for people who came to read at both colleges) … I didn’t pick up that there was anything special abt person in audience (I don’t know who that was) who was causing a disturbance—I didn’t sense that there was any 'argument’, just RC trying to shut the guy up so he cd go on w/ the labor of going through w/ reading he didn’t seem to be much interested in (probably not uncommon circumstance, since from that point forward, for another 30 years, RC doggedly went wherever he was asked to go to present his work … that in itself, to me, seems like a kind of 'hell’ … to arrive & 'be oneself’/be the poet everybody so much wants to hear read his poems (for the umteenth time) … I sure wldn’t want to do it !”

***** Sparrow 6, published in March of 1973, included the text of “The Creative,” a lecture delivered 10-21-72 at Johns Hopkins (a week after his mother’s death) and this poem.

June 12, 2015

No Relation

In the lead up to father’s day, I’ll be serially posting this essay on relation and the coincident, which is also a meditation on my father and Robert Creeley. Pictured above, my parents and I walking around Buffalo, summer 2005.

NO RELATION, for Tommy Joe Martin

I.

“And by the time my eyes were in my head they were in the houses that they would be in forever, in succession.” – Bobbie Louise Hawkins, Back to Texas

Robert Creeley died in Odessa, TX in 2005, but it wasn’t until recently that I began to think it significant that I also grew up there. Something about the way his place of death so often gets collapsed into the description “desert town,” elided in that way with so much desert elsewhere, lately makes me want to intercede on behalf of the unromantic desert.

Written from Marfa, TX, the last entry in Creeley’s Selected Letters has him riding off into the sunset, cowboyish—its inclusion as ‘the end’ positions it so, as more significant than it likely is, in the end, as a last dispatch (if it is one). Back turned to the politics of the artist colony, one can ride off into so many Marfa sunsets, but the drive north to Odessa sheds the romance from the thing.

In this selection, Creeley signs off wishing that all places could have the specificity of the border, which he’d just visited from his stay in Marfa. But the notion runs aground in his actual place of exit, where the curvature of the earth seems visible despite it being a basin, topographically. One looks out from Odessa to nothing but horizon on the horizon, but the place proposes an unobstructed view it can’t deliver.

My father kept a daily gas log for pretty much his entire adult life, and though the pocket calendars where he recorded mileage aren’t really forthcoming as diaries, sometimes he notes what seems major. In 1994, the year Creeley published Echoes, dad marked only two such events: once when he quit a job as a driller for RodRic, and once, on January 5, when the “Derrick blew over on Eve. Towr w/all d.c. and D.P. in it. Bad Wreck.”

He’d been in his off hours. Something had caught fire underground, and the explosion laid the rig flat. I think of him rushing out there when he heard there was a fire, all frantic when he talked to the daylight crew (d.c.) and told them to get everyone out because nothing could be done—all the concern of that appeal and his attempt to get to the rig as fast as possible. Wrongly, I haven’t often associated concern with his work life—it’s kind of feely for a man whose reputation was for expressing work feelings with his fists—but he was really worried for the men out there.

At the back of his gas logs, he kept phone numbers of hands he might call to assemble a crew. Next to some names, he’d note lasting impressions: Johnny Boss (no shit) was a “no-show, lazy.” Kenneth McDonald “quit, too old.” Among these men were the “slow witted,” the “drunk no show” and the occasional “good hand.” Many have no note at all, which I take to be generally fortunate.

In some of the logs, a Robert Duncan even shows up: no note, just a phone number (381-9423). Odessa’s a ways from Black Mountain, but I can’t help thinking how that other Duncan grew up in an oil town, too.

The coincident as “companionable form” (Coleridge, from the epigraph to Creeley’s Echoes).

It’s the occasion that needs to be located. To trouble why it occurs to me in the first place to tell the two stories at once (Creeley’s and my father’s). Or to write it as a way of finding the occasion of following it. So that tracing the coincident is as useful as articulating experience as part of some narrative or set of narratives.

Not argument that justifies the form of this writing, but the coincident.

Tale of some acts of some people, then, crossing or not, even missing a conjunction entirely. But co-incident in time, in memory (in my memory). Coincident in me.

Robert Duncan first appears in my dad’s gas logs in 1991. Other notable events that year:

1/15—“Deadline f/Hussein to Pull out of Kuwait or go to War w/U.S.A.”7/8—“Won our 1st 13 yr old All Star game 9-5 against Big Spring Internat’l.”

8/17—“Hurt my back”

8/29—“Air cond. Clutch blew up & Auto Cool wouldn’t stand behind their warranty”

8/31—“Replaced Windshield $110.00. hit a buzzard”

9/3—“Auto Cool Replaced bad air comp. f/nothing”

10/30—“1st Cold Spell”

In the summer he notes a week “off—on vacation.” This would have been a family trip to a timeshare in Granbury, TX, where my parents would move in 2001, and where my father and grandmother would die of injuries sustained in a tornado in 2013.

Creeley recalls in an interview an early conversation with Duncan, where the latter prods, “You’re not interested in history, are you?” Creeley’s response is difficult, really huge to me: “You know, and I kept saying, ‘Well, gee, I ought to be. And I want to be. But I guess I’m not. You know, I’d like to be, but, no, that’s probably not true.’ That history, as this form of experience, is truly not something I’ve been able to articulate with, nor finally engaged by” (88).

It’s a thorny claim for a poet. Thorny claim for a person, really. Can’t get down with history, eh? You know what they say about those types, don’t you?

But somehow Creeley’s response to Duncan’s pointed (but over simple) question has a proximity to my own sense of things growing up—that history happened elsewhere, as it were, and that the people in it weren’t the people in sight. It’s a class politics, that lie about significance, and it takes some effort to slough off.

Reading my dad’s gas logs alongside Creeley’s work might put a finer point on it: dad never talked much about himself. For all that Creeley seems to have wanted the same to be true for him, and for all the difficulty he traces, in his 1973 essay “Inside Out,” regarding autobiographical writing, and even though he claimed to write for an audience of one (himself), at some point there’s something inescapably social about putting it down so as to put it out there, for better or worse. Up next to what amount to mostly mileage and maintenance records, Creeley’s writerly sense of the problems of autobiography stands out as markedly public, avowedly historical.

The irony of his essay of course is that it engages a community for which going on record about the scene, or at least about one or two folks in it, is constitutive of its life and livelihood. It’s an interesting problem for a real person to feel compelled to promote one’s efforts or one’s peers’ efforts, especially in an “autobiographical mode” (problematized or not), and especially given some of Creeley’s more complicated formulations in this essay:

Autobiography might be thought of, then, as some sense of a life responsive to its own experience of itself. This is the ‘inside out,’ so to speak—somehow reminiscent of, It ain’t no sin/ to take off your skin/ and dance around in your boh-hones… Trying to take a look, see what it was all about, why Mary never came home and Joe was, after all, your best friend. Not to explain—that is, not to lay a trip on them—rather an evidence seems what one is trying to get hold of, to have use of oneself specifically as something that does something, and in so doing leaves a record, a consequence, intentionally or not. (CE 561)

Or, earlier, “Place is a real event—where you are is a law equal to what you are” (CE 559). The conjunction of person and place, understood as history (and invariably intersected with universe), is something Creeley might have learned from Olson and Williams (he could of course have learned it elsewhere). Maximus and Paterson can be read as in that way person-al poems. Meaning, it’s not really true he’s not interested in history, but that, at least according to him, experience as abstracted into historical narrative isn’t really his bag. The real event versus its timeline—the latter presumes a kind of distance, a more exhaustive understanding, but the real event would be something like relation—a local, intimate, coming to terms.

In “Away,” (the title poem from his 1976 Black Sparrow book, a poem written during roughly the same period as the essay), even this real event of place gets told to shove it:

Putting away place might be antisocial, but it isn’t necessarily anti-historical. It’s on a par with keeping a secret, maybe even announcing in the place of address so-called (i.e. in a poem made public—the place of whatever shapes that relation) this thing that won’t be shared. And it’s to report an anxiety about the social, I think—about ‘the so-called people’ and what goes on ‘where the heart is’—that seems to motivate much of Creeley’s writing during this time: “But who are you, and why does your life propose itself as a collective” (CE 560).

These things are really personal, but it’s a life among people that they sound against (so a social, a historical life). “Inside Out” begins with an untitled poem for Jane Brakhage (also included in Away, but without the dedication):

I’m telling you to let myself think, but not to be heard, really. The attitude makes for difficult relationships, for one. Makes relation difficult. These poems rail against, and yet also succumb to, the compulsion to recount a grief publicly—it’s trying that one would have recourse to writing in this situation (someone’s always listening in). The poems proceed by indicting whatever audience they might find for being there in the first place, taking whatever pleasure in listening.

In relation to much of what he might have wanted to tell me, I was never a great listener, and now I find myself straining to eavesdrop on my father’s daily life through these fragments, and wondering what he’d think of having me as an audience.

Julia and I have guessed at why he might have made these notes in the first place. I can’t know if he ever reread them, though he appears to have kept every log. Implicit in his more forthcoming entries seems often simply the feeling that someone—himself—should mark this, that it’s a remarkable fact.

If it’s simply that it was time to talk about it, then his notes share with Creeley’s poem for Jane Brakhage the sense that audience isn’t the motivating factor, that this instance of writing draws a relation, not between a writer and a reader, but between a person and some facts and questions, between a person and language. So, writing as relation, but not communication and not expression.

Relation but not address, in the end.

I think maybe he’d appreciate the irony that, when he intends no audience, he finally has my attention.

The poem for Jane Brakhage argues that the addressee is ancillary to the occasion. Though I don’t know what precisely elicited the dedication, I struggle to read it as devoid of personal invective—he’s the one who “knows better” etc. I think of those home movies released recently by Bobbie Louise Hawkins: the Creeleys and the Brakhages in the house in Placitas, getting stoned, showing off, and (presumably, though the footage is silent) talking shop.

Uttered in that context (but that isn’t the poem’s context), the intention would seem to be to silence the audience, to scold her into attention. But read aloud at a public event, say, I don’t imagine the sentiment would lose its teeth. So too, at least in part, the published poem.

But it’s tenuous to presume a link between the poem’s inception and its reception, where the reader’s relation to the text is somehow presaged in the moment of writing. In Creeley’s poems, these are more often fundamentally discrete events. I might recognize an anxiety about the social in Creeley’s poems, but I can’t presume to read myself into that crowd (even if here I am reading). It’s as useful to take him at his word, as it were, re himself as his only audience, and thus to attempt a reckoning with those relations that are prior to or in excess of that posited between ‘writer’ and ‘audience.’

All the more difficult when the writer is dearly departed.

June 4, 2015

brightpinkmosquito:

From Kathleen Fraser’s MAGRITTE SERIES,...

June 1, 2015

Kenneth Goldsmith Says He Is an Outlaw

Fred Moten, once again, has succinctly and powerfully captured what is at stake here. Gratitude to CAConrad for collecting these responses.

Fred Moten:

“I think you know you fucked up. But do you know why you fucked up? And

do you know how you fucked up? Do you know that why you fucked up and

how you fucked up are totally entangled? Do you know that entanglement

is given in the raciality of the concept, as such? I wish I could be

convinced that you’re thinking right now about how and why you fucked

up. I wish I could convince you that the continued existence of human

life on this earth depends upon you thinking about why and how you

fucked up.“

C.J. Martin's Blog

- C.J. Martin's profile

- 11 followers