No Relation

In the lead up to father’s day, I’ll be serially posting this essay on relation and the coincident, which is also a meditation on my father and Robert Creeley. Pictured above, my parents and I walking around Buffalo, summer 2005.

NO RELATION, for Tommy Joe Martin

I.

“And by the time my eyes were in my head they were in the houses that they would be in forever, in succession.” – Bobbie Louise Hawkins, Back to Texas

Robert Creeley died in Odessa, TX in 2005, but it wasn’t until recently that I began to think it significant that I also grew up there. Something about the way his place of death so often gets collapsed into the description “desert town,” elided in that way with so much desert elsewhere, lately makes me want to intercede on behalf of the unromantic desert.

Written from Marfa, TX, the last entry in Creeley’s Selected Letters has him riding off into the sunset, cowboyish—its inclusion as ‘the end’ positions it so, as more significant than it likely is, in the end, as a last dispatch (if it is one). Back turned to the politics of the artist colony, one can ride off into so many Marfa sunsets, but the drive north to Odessa sheds the romance from the thing.

In this selection, Creeley signs off wishing that all places could have the specificity of the border, which he’d just visited from his stay in Marfa. But the notion runs aground in his actual place of exit, where the curvature of the earth seems visible despite it being a basin, topographically. One looks out from Odessa to nothing but horizon on the horizon, but the place proposes an unobstructed view it can’t deliver.

My father kept a daily gas log for pretty much his entire adult life, and though the pocket calendars where he recorded mileage aren’t really forthcoming as diaries, sometimes he notes what seems major. In 1994, the year Creeley published Echoes, dad marked only two such events: once when he quit a job as a driller for RodRic, and once, on January 5, when the “Derrick blew over on Eve. Towr w/all d.c. and D.P. in it. Bad Wreck.”

He’d been in his off hours. Something had caught fire underground, and the explosion laid the rig flat. I think of him rushing out there when he heard there was a fire, all frantic when he talked to the daylight crew (d.c.) and told them to get everyone out because nothing could be done—all the concern of that appeal and his attempt to get to the rig as fast as possible. Wrongly, I haven’t often associated concern with his work life—it’s kind of feely for a man whose reputation was for expressing work feelings with his fists—but he was really worried for the men out there.

At the back of his gas logs, he kept phone numbers of hands he might call to assemble a crew. Next to some names, he’d note lasting impressions: Johnny Boss (no shit) was a “no-show, lazy.” Kenneth McDonald “quit, too old.” Among these men were the “slow witted,” the “drunk no show” and the occasional “good hand.” Many have no note at all, which I take to be generally fortunate.

In some of the logs, a Robert Duncan even shows up: no note, just a phone number (381-9423). Odessa’s a ways from Black Mountain, but I can’t help thinking how that other Duncan grew up in an oil town, too.

The coincident as “companionable form” (Coleridge, from the epigraph to Creeley’s Echoes).

It’s the occasion that needs to be located. To trouble why it occurs to me in the first place to tell the two stories at once (Creeley’s and my father’s). Or to write it as a way of finding the occasion of following it. So that tracing the coincident is as useful as articulating experience as part of some narrative or set of narratives.

Not argument that justifies the form of this writing, but the coincident.

Tale of some acts of some people, then, crossing or not, even missing a conjunction entirely. But co-incident in time, in memory (in my memory). Coincident in me.

Robert Duncan first appears in my dad’s gas logs in 1991. Other notable events that year:

1/15—“Deadline f/Hussein to Pull out of Kuwait or go to War w/U.S.A.”7/8—“Won our 1st 13 yr old All Star game 9-5 against Big Spring Internat’l.”

8/17—“Hurt my back”

8/29—“Air cond. Clutch blew up & Auto Cool wouldn’t stand behind their warranty”

8/31—“Replaced Windshield $110.00. hit a buzzard”

9/3—“Auto Cool Replaced bad air comp. f/nothing”

10/30—“1st Cold Spell”

In the summer he notes a week “off—on vacation.” This would have been a family trip to a timeshare in Granbury, TX, where my parents would move in 2001, and where my father and grandmother would die of injuries sustained in a tornado in 2013.

Creeley recalls in an interview an early conversation with Duncan, where the latter prods, “You’re not interested in history, are you?” Creeley’s response is difficult, really huge to me: “You know, and I kept saying, ‘Well, gee, I ought to be. And I want to be. But I guess I’m not. You know, I’d like to be, but, no, that’s probably not true.’ That history, as this form of experience, is truly not something I’ve been able to articulate with, nor finally engaged by” (88).

It’s a thorny claim for a poet. Thorny claim for a person, really. Can’t get down with history, eh? You know what they say about those types, don’t you?

But somehow Creeley’s response to Duncan’s pointed (but over simple) question has a proximity to my own sense of things growing up—that history happened elsewhere, as it were, and that the people in it weren’t the people in sight. It’s a class politics, that lie about significance, and it takes some effort to slough off.

Reading my dad’s gas logs alongside Creeley’s work might put a finer point on it: dad never talked much about himself. For all that Creeley seems to have wanted the same to be true for him, and for all the difficulty he traces, in his 1973 essay “Inside Out,” regarding autobiographical writing, and even though he claimed to write for an audience of one (himself), at some point there’s something inescapably social about putting it down so as to put it out there, for better or worse. Up next to what amount to mostly mileage and maintenance records, Creeley’s writerly sense of the problems of autobiography stands out as markedly public, avowedly historical.

The irony of his essay of course is that it engages a community for which going on record about the scene, or at least about one or two folks in it, is constitutive of its life and livelihood. It’s an interesting problem for a real person to feel compelled to promote one’s efforts or one’s peers’ efforts, especially in an “autobiographical mode” (problematized or not), and especially given some of Creeley’s more complicated formulations in this essay:

Autobiography might be thought of, then, as some sense of a life responsive to its own experience of itself. This is the ‘inside out,’ so to speak—somehow reminiscent of, It ain’t no sin/ to take off your skin/ and dance around in your boh-hones… Trying to take a look, see what it was all about, why Mary never came home and Joe was, after all, your best friend. Not to explain—that is, not to lay a trip on them—rather an evidence seems what one is trying to get hold of, to have use of oneself specifically as something that does something, and in so doing leaves a record, a consequence, intentionally or not. (CE 561)

Or, earlier, “Place is a real event—where you are is a law equal to what you are” (CE 559). The conjunction of person and place, understood as history (and invariably intersected with universe), is something Creeley might have learned from Olson and Williams (he could of course have learned it elsewhere). Maximus and Paterson can be read as in that way person-al poems. Meaning, it’s not really true he’s not interested in history, but that, at least according to him, experience as abstracted into historical narrative isn’t really his bag. The real event versus its timeline—the latter presumes a kind of distance, a more exhaustive understanding, but the real event would be something like relation—a local, intimate, coming to terms.

In “Away,” (the title poem from his 1976 Black Sparrow book, a poem written during roughly the same period as the essay), even this real event of place gets told to shove it:

Putting away place might be antisocial, but it isn’t necessarily anti-historical. It’s on a par with keeping a secret, maybe even announcing in the place of address so-called (i.e. in a poem made public—the place of whatever shapes that relation) this thing that won’t be shared. And it’s to report an anxiety about the social, I think—about ‘the so-called people’ and what goes on ‘where the heart is’—that seems to motivate much of Creeley’s writing during this time: “But who are you, and why does your life propose itself as a collective” (CE 560).

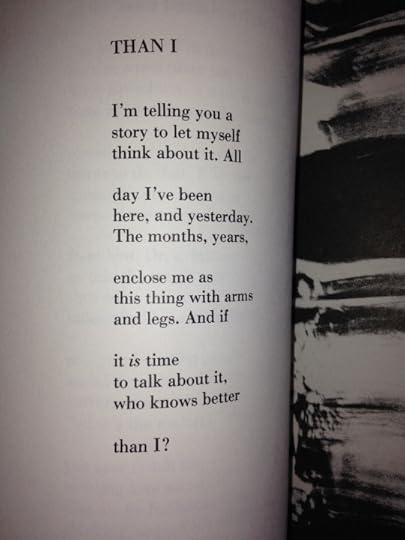

These things are really personal, but it’s a life among people that they sound against (so a social, a historical life). “Inside Out” begins with an untitled poem for Jane Brakhage (also included in Away, but without the dedication):

I’m telling you to let myself think, but not to be heard, really. The attitude makes for difficult relationships, for one. Makes relation difficult. These poems rail against, and yet also succumb to, the compulsion to recount a grief publicly—it’s trying that one would have recourse to writing in this situation (someone’s always listening in). The poems proceed by indicting whatever audience they might find for being there in the first place, taking whatever pleasure in listening.

In relation to much of what he might have wanted to tell me, I was never a great listener, and now I find myself straining to eavesdrop on my father’s daily life through these fragments, and wondering what he’d think of having me as an audience.

Julia and I have guessed at why he might have made these notes in the first place. I can’t know if he ever reread them, though he appears to have kept every log. Implicit in his more forthcoming entries seems often simply the feeling that someone—himself—should mark this, that it’s a remarkable fact.

If it’s simply that it was time to talk about it, then his notes share with Creeley’s poem for Jane Brakhage the sense that audience isn’t the motivating factor, that this instance of writing draws a relation, not between a writer and a reader, but between a person and some facts and questions, between a person and language. So, writing as relation, but not communication and not expression.

Relation but not address, in the end.

I think maybe he’d appreciate the irony that, when he intends no audience, he finally has my attention.

The poem for Jane Brakhage argues that the addressee is ancillary to the occasion. Though I don’t know what precisely elicited the dedication, I struggle to read it as devoid of personal invective—he’s the one who “knows better” etc. I think of those home movies released recently by Bobbie Louise Hawkins: the Creeleys and the Brakhages in the house in Placitas, getting stoned, showing off, and (presumably, though the footage is silent) talking shop.

Uttered in that context (but that isn’t the poem’s context), the intention would seem to be to silence the audience, to scold her into attention. But read aloud at a public event, say, I don’t imagine the sentiment would lose its teeth. So too, at least in part, the published poem.

But it’s tenuous to presume a link between the poem’s inception and its reception, where the reader’s relation to the text is somehow presaged in the moment of writing. In Creeley’s poems, these are more often fundamentally discrete events. I might recognize an anxiety about the social in Creeley’s poems, but I can’t presume to read myself into that crowd (even if here I am reading). It’s as useful to take him at his word, as it were, re himself as his only audience, and thus to attempt a reckoning with those relations that are prior to or in excess of that posited between ‘writer’ and ‘audience.’

All the more difficult when the writer is dearly departed.

C.J. Martin's Blog

- C.J. Martin's profile

- 11 followers