C.J. Martin's Blog, page 12

April 19, 2015

susanlanders:

Mean boys.

Jesus.

April 15, 2015

April 13, 2015

Co-eternal Beam: Norma Cole’s Art : Laura Moriarty : Harriet the Blog : The Poetry Foundation

Julia and I were able to see this show when we visited Michael Cross earlier this year, and afterwards we met with Norma and all decided to produce a book of her visual art when she’s ready. In the meantime, read Laura’s wonderful post about Norma’s visual work, and if you want to purchase prints by her, we have three for sale:

Norma Cole’s Spicer broadsides (2): http://furtherotherbookworks.tumblr.com/post/113719105158/jack-spicer-broadsides-four-unpublished-poems

Norma Cole & C.J. Martin broadside: http://furtherotherbookworks.tumblr.com/post/45496839902/norma-cole-c-j-martin-2012-17-x-22

April 12, 2015

On poetry, #6: beauty, the senses, & what must be doubly engineered

A poem can point to what is beautiful. Here is one I just wrote for you:

A COMMA-SHAPED ROBIN

I mean to tell you a robin shaped like a pause is beautiful. But of all the things that pointing to beauty does, it also sets into motion a pattern of exception. There is a “but.”

A poem pointing to beauty can be doubly engineered, first with the requirement of beauty, second with beauty’s I’m-sorry conscience and sorry self-defense.

The robin I saw yesterday, shaped like a comma, was shaped like a comma because it was hit by a car and dead. I don’t want to write that poem, so imagine that “A COMMA-SHAPED ROBIN” is in the middle of a white page, and I am a poet in a lazy despair so the white page is the field of how it is dead.

If a poem successfully brings me to beauty, I do not trust its apology. If it successfully apologizes, I do not trust its beauty.

Or, what I trust in poetry becomes neither beauties nor apologies. The other day Cassandra Gillig and I accidentally found ourselves in a carcass shop – “miscellaneous teeth: 25 cents” – and it was such a stylish contemporary place that I coined a new epithet for my city – “the city of gentrified death.”

Then I thought about how cities are often so beautiful

as are the remnants of death, when dried up and put in antique cabinets and display cases like that,

and how all cities are cities of gentrified death.ARE POEMS LIKE CITIES?

(if poems are like dreams and dreams are like cities: yes

and : I dream in architecture and city planning, the peripheries of conference centers, the lower levels of stadiums, in follies and street numbers and skywalks, too)(2)

Here is William Blake’s strategy for the double engineering of beauty and its exceptions.

In one category, INNOCENCE, Blake places what is not known and therefore beautiful (the infant joy is only the infant joy for how it remains unnamed/unregistered) and in this other, EXPERIENCE, is the hostile world where all has been legislated, owned, articulated, and mapped. From his poem London:

I wander thro’ each charter’d street,

Near where the charter’d Thames does flow.

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.In every cry of every Man,

In every Infants cry of fear,

In every voice: in every ban,

The mind-forg’d manacles I hearHow the Chimney-sweepers cry

Every blackening Church appalls,

And the hapless Soldiers sigh

Runs in blood down Palace wallsThe senses in this poem become disarrayed. Blake hears the mind-forg’d manacles rather than sees or feels them. The handcuffs are forged in the fires of ideology: but what sound does an ideologically misshaped metal make? You must “hear” the meaning of the city for the nature of the city is the magnificence of its sights obscures the underlying discourse of its laws. It is the discourse of its laws, though, that make the city “experienced” / what is not beautiful.

When you walk through your city do you hear blood running down the palace walls? And what do you do with your city when even the water is heavy with property? What is the relationship of law to a map? Is it a city of gentrified death?

I’ve written someplace before — “some had a map / some had loud keys” — that dronecore / the cartographied-

(3)

The Marxist critic E.P. Thompson wrote at length on this poem, but he doesn’t mention the primacy of the act of hearing in it – “every reader, without help of a critic, can see Blake’s London,” he writes, that this poem is particularly “lucid” — suggesting again that what is in the poem/through the poem is something to be seen. But the thing about the poem is that if it is lucid, it is lucid insofar as it moves away from sight.

The beauty we _see_ can be a problem. Our sight, of all senses, is that which most deceives because to see is to believe, unfortunately. Urbanity (and capital) can mean dazzled eyes, even when every other part of us hurts.

So Blake moves the poet’s vision to his ears: how can a sigh be blood on a palace wall? In this poem there are three cries, one curse, and one sigh. Of the other things heard: bans, voices, and manacles. At this point in English, appall is transitive, and means a kind of spoken curse, so even the church is doing a lot of talking. There is so much vivid noise and in this noise, then, the world of appearances of the city is rent open and what is terrible in it exposed not as seen thing, but a set of sounds.

Poetry, because it requires no materials but language, can give speech of the speechless, reveal objects and environments that utter (scream, wail, cry) beyond the first speech of their appearance. Blake giving speech of the speechless is half the game of Songs of Innocence and Experience - when he is not actually giving speech to the speechless he is asking the speechless things of the world to give us speeches. Blake asks the tiger, the lamb, the garden of love, the infant, to speak. When the speechless things don’t answer — (these poems of the interrogatory mode) — their silence is a third operation. This is because too often we already know their answers. What is beautiful is what does not say. And what does not say we might want to think twice about trusting (on first sight). That’s what’s in London, as it is often is, as cities are like poems are like chains of exception are like everything that hangs on a “but.”

April 11, 2015

Wo(o)lf- ish reading

Some more to add to my Jigsaw Puzzle - chewing a few pieces to make them fit

***

(Appetizer)

“-Today, she asked me what “Genius” meant? I told her none had known-“ Dickinson

(main coarse)

"Wonderful to relate, poets have found religion in nature; people live in the country to learn virtue from plants. It is in their indifference that they are comforting. That snowfield of the mind, where man has not trodden, is visited by the cloud, kissed by the falling petal, as, in another sphere, it is the great [white, male] artists, the [Melville’s] and the [Spicer’s], who console not by their thought of us by by their forgetfulness.”

“Rashness is one of the properties of illness-outlaws that we are- and it is rashness that we need in reading [Spicer]. It is not that we should dose in reading him, but that, fully conscious and aware, his fame intimidates and bores, and all the views of all the critics dull in us that thunder-clap of conviction which, if an illusion, is still so helpful an illusion…With all this buzz of criticism about, one may hazard one’s conjectures privately, make one’s notes in the margin; but, knowing that someone has said it before, or said it better, the zest is gone. Illness, in its kingly sublimity, sweeps all that aside and leaves nothing but [Spicer] and oneself. What with his overweening power and our overweening arrogance, the barriers go down, the knots run smooth, the brain rings and resounds….” – both quotes from Woolf’s “On Being Ill”

(Dessert)

Re: previous on reading & unanticipated/uninvited audiences + as reader who writes etc.: what if, rather than (or in addition to?) a future-ly “ideal reader”, one’s reader is already dead? I see this concern squirming around in Spicer’s work, particularly in Textbook - where writer/reader positions freely mix -particularly in dictation - …A readerwriter coagulation that obscures - and is an obfuscation of- a wound.

(Mint)

Which leaves me to chew on Woolf’s kingly + wound & reading particularly as (unproductive [as]) illness ….I am not yet full….

April 10, 2015

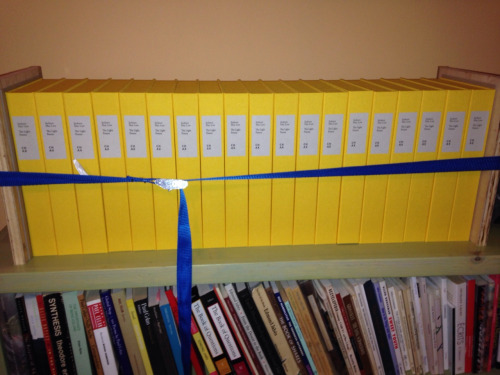

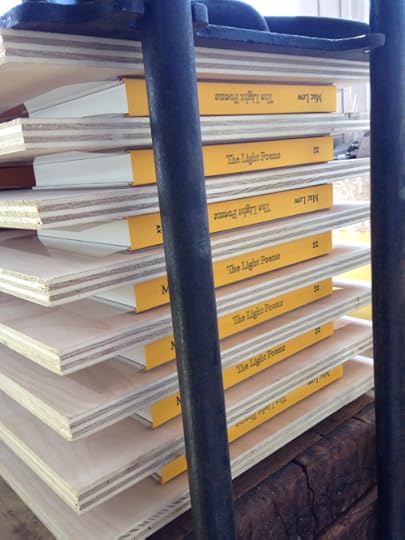

furtherotherbookworks:

Coming to the end of the work for Chax!...

April 9, 2015

Norma Cole, from the How(ever) archives:...

Norma Cole, from the How(ever) archives: https://www.asu.edu/pipercwcenter/how2journal/archive/print_archive/cole.html

April 5, 2015

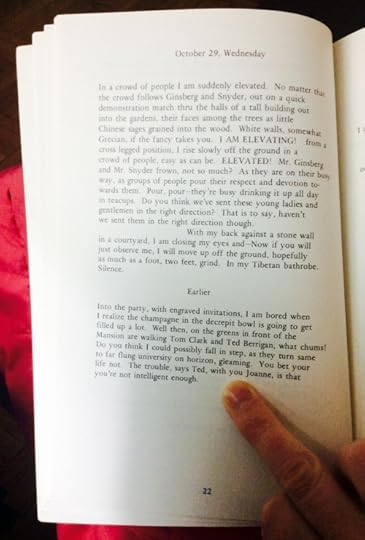

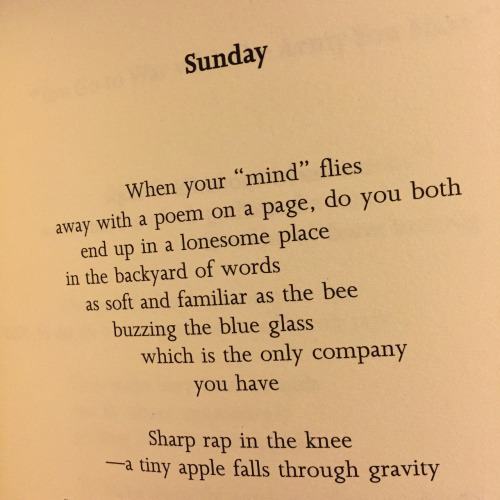

jeandonnelly:

Joanne Kyger, from On Time (City Lights)....

April 1, 2015

on poetry, #1

It’s hard to not hate April, even when it marks the spring in which you are unexpectedly not dying, because April is the month of the performative self-loathing of poets and an equally boring performative poetry-loving of institutions. It’s an exasperating symbiosis. The poet says terrible things about poetry, meaning themselves, while at the same time they take a check for being a poet in public in April, that check and its issuer part of what they should be saying terrible things about in the first place. But they do not say terrible things about the check, its issuer, about money itself, about the way it grows itself in markets, about what these markets mean against our ability to live in the kind of way that would make a real poetry finally possible. Instead, it is poetry itself to blame for the state of poetry, not the absurd horror of the conditions in which poetry persists, as a kind of noise and weak rebuttal, once in a while delivering out of the grim shit of modernity a semi-articulate word in response. (even if sometimes this word is only “ouch”)

For example, literature itself is often a terrible institution, written in the blood of those who suffer empire and the sweat of the invisible labor of mostly invisible women and children. But literature hasn’t always been around. It’s historical: you may find its beginnings, you can, if you have a good imagination, imagine its endings, imagining also that poetry is not dependent upon literature to exist. Literature exists because governments do, but governments do not have to exist, and sometimes poems can point to this. Because poems use language to create what hasn’t been before, they can remind us of what doesn’t have to be, or what could be. They (along with the people who write them) can take a piss on the office of every minister of culture, even if in the US we are so hateful, or so good at camouflaging every enemy to our happiness, that we do not even have such an office at which to aim our stream.

There is a lot of self-loathing and vapid boosterism in April, but there is little consideration of poetry’s possible uses against conditions, because along with this performative self-loathing is a common blithe acceptance of the hegemonic claim of poetry’s uselessness. Despite all the ordinary evidence of poetry’s relationship to feeling and feelings relationship to action (among other things, like poetry’s useful tradition of encoded speech in which one can offer life-saving and revolutionary directions without being put to trial for this—diane di prima—or the easy way that lyric poems can be memorized, so that people can take them into distressing situations that lack objects by only holding them in their heads—claude mckay) poets would insist that a vast range of something that a poem can do is actually in the category of “nothing.”

I don’t hate poetry. No one is paying me for it, but I think this month, to try to correct the general unhappiness, I will try to write about it every day, of at least as much as possible. But first, here is a poem by a Venezuelan revolutionary poet of the 20th century, Victor Valera Mora:

EVEN IN THE MIDST OF TERRIBLE STORMS

Even in the midst of terrible storms

I have always chosen to defend

the dignity of poetry

Return it to its origins

Its dazzling many-edged blade

March 31, 2015

portlandpoetry:

Allison Cobb at À reading #15March 2015

C.J. Martin's Blog

- C.J. Martin's profile

- 11 followers