Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2419

February 15, 2011

After Moore's Law

Let me begin this post with a confession of total ignorance as to what the physical basis, if any, of "Moore's Law" is but I kind of have this pet notion related to it that Kevin Drum inadvertently reminded me of:

World-changing inventions just don't come around all that often, and when they do it takes a long and variable time for them to become integrated enough and advanced enough to have an explosive economic effect. Steam took the better part of a century, electrification took about half that, and computers — well, we don't really know yet. So far it's been about 60 years and obviously computers have had a huge impact on the world. But I suspect that even if you put the potential of AI to one side, we're barely halfway into the computer revolution yet. To a surprisingly large extent, we're still using computers to automate stuff we've always done instead of actually building the world around what computers can do.

My pet notion is that improvements in computer power have been, in some sense, come along at an un-optimally rapid pace. To actually think up smart new ways to deploy new technology, then persuade some other people to listen to you, then implement the change, then have the competitive advantage this gives you play out in the form of increased market share takes time. The underlying technology is changing so rapidly that it may not be fully worthwhile to spend a lot of time thinking about optimizing the use of existing technology. And senior officials in large influential organizations may simply be uncomfortable with state of the art stuff. But the really big economic gains come not from the existence of new technologies but their actual use to accomplish something. So I conjecture that if after doubling, then doubling again, then doubling a third time the frontier starts advancing more slowly we might actually start to see more "real world" gains as people come up with better ideas for what to do with all this computing power.

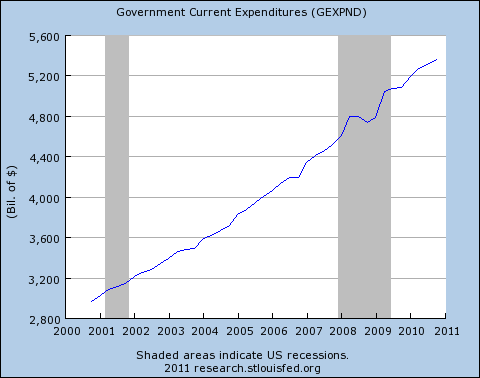

Re-Litigating The Stimulus

Karl Smith wants to relitigate the debate over the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act:

Now, in contrary I don't think Obama should have started with a number for spending – though that would have been preferable to what happened.

I would have started with a much higher number for tax cuts. Indeed, "the stimulus" could have been exclusively tax cuts and much much bigger ones. As I floated before, there was the possibility of simply suspending the payroll tax entirely.

I think this proposal gets at what I've (creatively!) called the trouble with fiscal stimulus. The two best ways to implement discretionary fiscal stimulus on a timely, scalable basis are general revenue sharing with state and local governments and payroll tax cuts. But the progressive coalition would fear (not unreasonably) that tax cuts tend not to stay temporary (see how Republicans and moderate Democrats felt about the expiration of the Bush tax cuts) so any such measure would merely increase the pressure for Social Security cuts. Meanwhile, the conservative coalition would fear (also not unreasonably) that bailouts of state and local government would fuel growth of the overall public sector. The state/local budget crisis is a disaster for macroeconomic stability, but it's a huge opportunity for people who think there's a lot of waste in state/local government as witnessed not only by Republicans like Chris Christie and Scott Walker but also by Andrew Cuomo and Rahm Emanuel.

The underlying pathology here is a total lack of political consensus about the appropriate size of the public sector that makes it impossible for anyone to credibility commit to temporary fiscal policy measures. Progressives accurately suspect conservatives of welcoming budget disasters as a tool for forcing program cuts and conservatives accurate suspect progressives of wanting to use stimulus as a vehicle for funding programmatic expansions we favor on the merits. Countries like Germany and Sweden who entered the recession with more consensus about the size of the public sector ended up with more net stimulus despite less Keynesian political cultures.

What's desperately needed is a systematic reform of state/local budget procedures so that macroeconomic stabilization is less hostage mid-crisis congressional bargaining.

Is There a Traffic Bubble, Or Does The New York Times Have an Inefficient Capital Structure?

As I hope my family can attest, I made a great point over dinner a couple of weeks ago about how the New York Times is clearly undervalued vis-a-vis various internet stocks. The NYT's not an "internet company" but it does run one of the world's most popular websites. Then I forgot all about it. But via Ezra Klein, I have a chance to revisit the point via Frédéric Filloux contention that we're experiencing a web traffic bubble:

About 35% of the HuffPo's users come form Google. They land on cleverly optimized content: stories borrowed from other (and consenting) medias that mostly generate blogging and comments. This is the machine that drove 28m unique visitors in January, which makes the HuffPo close to the New York Times/Herald Tribune audience of 30m UV. With one key difference: each viewer of the NYT websites yields an ARPU of $11, ten times more than the Arianna thing. Based on the HuffPo's valuation, the NYT Digital would be worth billions. That's a consolation.

You can think of some rational reasons for Huffington Post to get a premium over the NYT, related to HuffPo's more favorable labor cost structure. You can also assume they're getting a certain AOL desperation premium.

But is the basic thesis that the NYT should be worth a ton of money really so absurd? It's an iconic global brand whose main competition as an iconic serious English-language global media brand is owned by the UK government. The New York Times Company currently has a market capitalization of about $1.5 billion and if their P/E ratio were at the S&P 500 average, it would in fact be worth "billions" right now. So why isn't it? If I'm so smart why don't the markets agree? Well, it's a family controlled company with a two-tier stock structure. There's got to be some reason most firms aren't organized this way, and presumably the reason is that you pay a penalty in terms of the price of your equity. That's a price the Sulzberger family has historically been willing to pay in order to preserve the family's control over the iconic brand in question—they've viewed staying involved and maintaining their vision of the paper's mission as important enough to weigh against some more narrowly commercial considerations. That seems like a sensible view to me, but it's also sensible for investors to penalize them for it.

Recall that when Carlos Slim was given the opportunity to make an unorthodox investment in the NYT he wound up making a bunch of money.

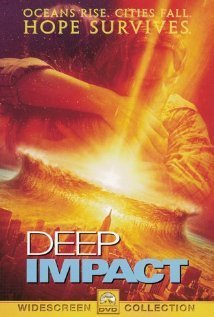

Asteroids and Absurdity

Sasha Volokh explains why highly moralized versions of libertarianism are totally absurd:

On the other hand — and at the risk of confirming Mark Kleiman in his belief that libertarians are loopy — I don't speak for all libertarians, but I think there's a good case to be made that taxing people to protect the Earth from an asteroid, while within Congress's powers, is an illegitimate function of government from a moral perspective. I think it's O.K. to violate people's rights (e.g. through taxation) if the result is that you protect people's rights to some greater extent (e.g. through police, courts, the military). But it's not obvious to me that the Earth being hit by an asteroid (or, say, someone being hit by lightning or a falling tree) violates anyone's rights; if that's so, then I'm not sure I can justify preventing it through taxation.

Bryan Caplan once suggested the asteroid hypo to me as a reductio ad absurdum against my view. But a reductio ad absurdum doesn't work against someone who's willing to be absurd, and I may be willing to bite the bullet on this one.

I think this is a mistake about how a reductio works. The mere fact that Volokh is willing to bite this bullet has no real bearing on the fact that the conclusion is clearly false, and so the argument is either logically invalid or else proceeds from false premises. I'd say "false premises." The best liberal thinking—classical, modern, whatever—proceeds from broadly consequentialist ideas about making human beings better off.

Rethinking Grand Bargaining

Elizabeth Drew's reporting that "the White House and Republican congressional leaders, in private talks, have agreed on the need to try to reach a bipartisan 'grand bargain' over the budget—a sweeping deal that could include entitlements and tax reforms as well as budget reduction" is being, I think, widely misunderstood in the blogosphere. I have had the opportunity, from time to time, to ask senior people in the administration how they envision the long-term fiscal gap being closed. The answer is that they expect a negotiated grand bargain.

And I wouldn't be surprised to learn that congressional Republican leaders say the same thing privately, or even that they privately say the same thing to the White House. After all, key congressional Republicans recently participated in the White House-instigated Simpson-Bowles exercise, which was precisely an effort to reach such a grand bargain. So presumably they do, in fact, agree with the White House that what's needed is a grand bargain. None of that is the same as saying that they're any closer to reaching agreement on a grand bargain than they were the day Simpson-Bowles came out and immediately had its recommendations repudiated by everyone involved.

I actually think the real issue here is that the fetishization of the grand bargain is part of the problem. Explanation and solution below the fold!

The biggest issues with the budget are that the lowest-hanging fruit is the stuff with the toughest interest-group opposition and the public doesn't like to confront the stark choices involved. What happens when you pursue the elite bargain strategy is that first you have to saw off any policy options that are key ideological bugaboos. So you end up proposing a regressing tax increase that isn't a carbon tax, which is insane. And then you present a document that (a) offers something for everyone to hate, and (b) leaves the possibility of just saying "no, let's not do this." The result is that you don't solve the problem.

A much better approach would, I think, be modeled on the idea of arbitration. Like suppose ten years from now faced with continuing paralysis, the failure of the Bayh-Brown Commission, and imminent national bankruptcy, General McMaster reluctantly finds himself leading a coup d'état (at the private urging of Chinese and European leaders) to ensure the bills keep getting paid and the global economy doesn't melt down.* But he wants it to be a friendly coup and has no intention of entrenching military government. So he calls me up and says "hey, Yglesias, you have a lot of impractical pie-in-the-sky ideas—what could be do to create a sustainable budget solution that has democratic legitimacy?"

Thus, my idea: You need not one commission, but two. One, the Red Commission, composed of and staffed by conservatives. The other, the Blue Commission, composed of and staffed by progressives. Both commissions have nine months to develop their proposals. At the end of the nine-month period, the proposals are unveiled and 30 days later there's a plebiscite on which proposal the nation will adopt. Whoever wins, wins has their plan adopted and then there's the whole messy question of re-transitioning to civilian government.** The point of the exercise is that instead of getting "grand bargainy" proposals out of this that everyone hates, you instead get proposals that move from the outside-in. This, I think, gives the commissioners the right incentives. You have to ask yourself not "what's the thing that a Republican Senator is likeliest to agree to" or "what would I do if I were policy dictator" but "what's the best compromise between my dream scenario and my goal of persuading the median voter that I'm right." You'd be challenging each side to put its best ideas forward, instead of its most mealy-mouthed and compromise-y.

* I hope this doesn't happen.

** In practice, very difficult and a good reason to hope we don't have a coup.

Better Transportation Grants

The Obama administration's relatively modest high-speed passenger rail funding commitments have attracted a lot of discussion because I think it basically plays as a culture war issue. But the FY 2012 Transportation budget offers a couple of ideas that I think are probably more significant, because they entail tying medium-sized federal grants to changes in state policy. That means they could end up leveraging much more money than is actually spent. Here's one idea that's primarily focused on improved safety:

Provides "Transportation Leadership Awards" to Drive State Reform. The Administration's six-year reauthorization plan would dedicate nearly $32 billion for a competitive grant program designed to create incentives for State and local partners to adopt critical reforms in a variety of areas, including safety, livability, and demand management. Federally-inspired safety reforms, such as seat belt and drunk-driving laws, saved thousands of American lives and avoided billions in property losses. This initiative will seek to repeat the successes of the past across the complete spectrum of transportation policy priorities. The Department will work with States and localities to set ambitious goals in different areas—for example, passing measures to prevent distracted driving (safety) or modifying transportation plans to include mass transit, bike, and pedestrian options (livability)—and to tie resources to goal-achievement.

This is important. Automobile accidents are a major cause of poor health outcomes (up to and including death) in the United States and it's considerably more cost effective to spend money on improving safety than to spend the money on patching people up after they've been in an accident. Even if it cost more to prevent accidents than to provide health care (which it doesn't), you'd obviously strongly prefer to avoid the pain and suffering in the first place.

Another idea is to fix the scandalous tendency of our current system to encourage people to build new roads even while existing roads are starved of maintenance:

Adopts a "Fix-It-First" Approach for Highway and Transit Grants. Key elements of the Nation's surface transportation infrastructure—our highways, bridges, and transit assets—are not up to standards. At the same time, States and localities have incentives to emphasize new investments over improving the condition of the existing infrastructure. The Administration's reauthorization proposal will underscore the importance of preserving and improving existing assets, encouraging its government and industry partners to make optimal use of current capacity, and minimizing life-cycle costs through sound asset management principles. Accountability is a key element of this system: States and localities will be required to report on highway condition and performance measures.

This is a great idea. The way we do things now is environmentally destructive and also extremely wasteful of the country's existing capital stock.

My pet idea in this space is that strong preference should be given in infrastructure funding to states and localities that are willing to re-zone in favor of higher density. Basically if your town or neighborhood wants better infrastructure just to serve its existing citizens, it ought to pay for that infrastructure itself. The country should "win the future" by investing its money in places that are eager to have higher populations in the future than they have at present. That idea might or might not fit under the "livability" heading DOT's currently offering, but it sort of cuts across the DOT and HUD policy spaces.

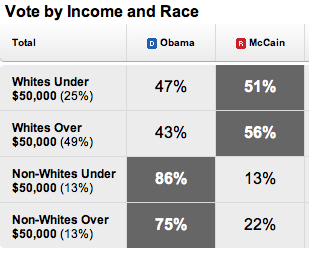

The Base and Bloggers

One of the most important facts about present-day American politics is that poor people have essentially no political "voice" in Washington. They do, however, vote. And they're also human beings with moral worth and interests who count. What often winds up happening is that you get liberal bloggers, whose opinions about things are easy to find out since we publish them on the Internet, used as a generalized proxy for a huge swathe of the electorate. Hence this kind of thing from Michael Shear:

One liberal supporter who listened to the [conference] call described it as "mostly boring," an indication that the president's base was not particularly upset about the budget. During the call, Mr. Plouffe also offered some comfort to the bloggers by suggesting that Mr. Obama is not interested in big reductions in Social Security.

As a colleague of mine snarks, "because if one thing is indicative of how poor people feel about cuts, it's white upper class bloggers."

Right. As best I can tell the electoral base of the Democratic Party continues to be low-income people and racial minorities. Obviously better-off white people with idiosyncratic ideological motivations also play an important role in progressive politics on a practical level. But I often thought during the health care debate that poor people would be saying "hell no I'm not going to give up this Medicaid expansion so you can hold out indefinitely for a public option." Conversely, the political tactics of calling for an overall discretionary budget freeze while insisting on investments in energy, infrastructure, and education has a lot of merit but it necessarily entails taking the hammer to programs that subsidize consumption for poor people. I kind of doubt that all that many LIHEAP recipients eagerly downloaded the budget yesterday morning and then blogged about it in the afternoon and got on a press call in the evening.

Lucky Duckies

I don't think we should cut Social Security benefits. But if we are going to cut Social Security benefits, I think it doesn't make sense to do what the Obama administration has done and make "No current beneficiaries should see their basic benefits reduced" one of the bargaining points.

After all, this isn't how any other kind of benefit cuts work. When Obama proposes cutting oil and gas subsidies, they propose cutting them right away. When Obama proposes a nominal freeze in federal pay, he's proposing a real cut right away. When LIHEAP gets the ax, it gets the ax right away. When Arizona cuts Medicaid, people can't get organ transplants right away.

And on the politics, it's a mess. Right now we have conservatives simultaneously calling for huge spending cuts and also getting the line's share of old people's votes even while the vast majority of non-security spending is on old people. In essence, by first separating the domestic budget into "discretionary" and "entitlement" portions and then dividing the entitlement programs up into "what today's old people get" versus "what tomorrow's old people will get" the political class has created a large and vociferously right-wing class of people who are completely immune from the impact of their own calls for fiscal austerity. In my view, that reality is the biggest driver of our current political dysfunction. There's some need for spending to be lower over the long term than it's currently projected to go and I think it's politically and morally vital that the adjustments be made in a balanced way. You frequently hear of the need to exempt everyone over the age of 55 from any possible cuts. That's nice for them and encourages them to go right on complaining about out of control spending. But the average 55 year-old will still be alive and collecting benefits in 2035 so the long-term budgetary implications of this "let the geezers keep their full benefits while they whine about how Democrats are bankrupting the country" are actually pretty significant.

If I were the president, my line would be closer to the reverse: I don't want to cut Social Security benefits for anyone, but if the Republicans want to tempt me into a compromise they're going to need to make sure that their own core constituency—people born before 1955 or so—pay a fair share of the price. Progressives don't need to indulge the premises of this "welfare state for me but not for thee" brand of conservatism that's taken over the country.

February 14, 2011

Endgame

They won't follow me:

— The team would appreciate it if you would visit the new ThinkProgress Facebook page and say you 'like' us.

— What happens when the bank forecloses on your landlord.

— The House GOP's war on contraceptives.

— The House GOP's plan to make it easier for terrorists to get nuclear weapons.

— Trouble in socialized medicine paradise.

— Noam Scheiber profiles Tim Geithner.

Arcade Fire, "Black Wave, Bad Vibrations".

Iran Isn't Winning the Future

Matt Duss reports from Israel's Herzliya Conference, a.k.a. "Neocon Woodstock":

The drummers were already going to have trouble keeping the beat in the wake of outgoing Mossad chief Meir Dagan's and Deputy Prime Minister Moshe Ya'alon's recent statements that efforts at sabotage and international sanctions had likely delayed an Iranian nuke for several years. Egypt only made things more complicated. Still, it was odd to hear neoconservative doyenne Danielle Pletka of the American Enterprise Institute dismiss as "propaganda" former Mossad head Efraim Halevi's assertion that "the US and Israel are winning the war against Iran." "If Iran is losing, I'd like to be that kind of loser," Pletka said, reminding the audience that, "Khomeini referred to Israel as a one bomb country."

"What I'm saying is not propaganda," Halevi shot back. "The danger is believing the propaganda of others."

It's amazing to me how this particular cast of mind manages to consistently overrate the success of dysfunctional political and economic systems. Israel has about twice Iran's per capita GDP, has an actually functioning nuclear arsenal, counts the mightiest empire the world has ever known as an ally, has a more potent conventional military, and manages to not be under international sanctions. But most of these advantages are either going to be frittered away, or else simply not matter, if the Israeli government persists in trying to hold on to and even expand settlements in the West Bank and East Jerusalem.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers