Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2418

February 16, 2011

The Tyranny of Numbers

On the subject of Social Security, I think people sometimes get tripped up by over-emphasis on numerical quantities when thinking about this kind of issue. Obviously at some point you have to get down to dollars and cents. But at an initial phase, it's helpful to think of this as more of a geometry problem than a algebra problem.

Here's what we think we know about the geometry of the future of America:

One: There will be more people overall.

Two: There will be more stuff overall.

Three: The overall ratio of stuff to people will be higher.

Four: The share of elderly people to in the overall population will be higher.

Now think of the country as composed of two kinds of people, the retired and the non-retired both of whom consume some stuff. Fact four leaves us with the following choices:

One: A larger share of elderly people can be non-retired.

Two: We can import additional non-retired people to prevent the ratio from shifting.

Three: The average retired person can consume a smaller share of stuff.

Four: The average non-retired person can consume a smaller share of stuff.

Proposals to accomplish number one are frighteningly common in Washington and normally go by the name "raise the retirement age." This is very regressive and I don't like it at all. Proposals to accomplish number two I like a lot, but seem to have been arbitrarily ruled off the table as an option. This leaves us with three and four. The point here is that if a larger slice of the population pie is composed of old people, then either the elderly consumption pie needs to be sliced thinner or else the non-elderly consumption pie needs to be smaller.

Since we're talking about a higher overall quantity of stuff per person, nobody actually needs to be worse off in the future but if the share of elderly people in the population grows then the consumption shares need to adjust one way or the other. Then in terms of programs to assign slices to old people, who have two big ones. One, Social Security, gives money to retired people which they use to buy stuff. The other, Medicare, buys health care (which is a kind of stuff) on behalf of retired people. You can fiddle with retired people's share of "stuff" by fiddling with either program but the implications are quite different. For example, if you're a hospital administration you really really really want the government to keep buying lots of health care for old people but don't really care about old people's ability to buy stuff. If you're a nutritionist, you probably think that old people's ability to buy healthful food has really important implications for their level of health and well-being.

Everything Is a Pyramid Scheme

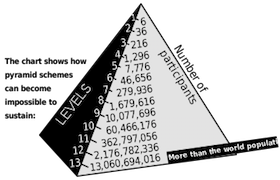

Erica Greider has a and Jonathan Bernstein has a variety of gripes with her, including "Note too that Grieder calls Social Security a 'pyramid scheme,' which is also common usage and also totally wrong."

I think perhaps the best way to describe what's wrong with this is to observe that on an adequate level of generality everything is a pyramid scheme. Imagine a country with no Social Security. People would still presumably want to structure their lives such that for a while they produce more than they consume, and then later in life when they're old they consume more than they produce. The only way for this to work is for them to save money in vehicles that earn a positive rate of return and the only way for that to happen on average is for the future economy to be larger than the present economy. That, in turn, relies on population growth and productivity growth. If population growth slows, you're going to have a problem. In a pyramid scheme, everyone makes money until you run out of new people to bring into the scheme. Similarly, if you imagine a country with no children and no immigrants then clearly the economy is going to go bust once it starts running out of new workers. But the fact that it would go bankrupt if the country ran out of people doesn't make Wal-Mart a "pyramid scheme" and Social Security's no different from Wal-Mart in its implicit assumption that there will continue to be new people in the future.

The difference between a government program founded on an assumption about future population growth and a private investment founded on an assumption about future population growth is this. If your private investment turns out to be founded on a small but meaningful miscalculation, the adjustment happens automatically. If your government program turns out to be founded on a small but meaningful miscalculation, the adjustment requires an act of congress. But the facts about the quantity of real resources available aren't affected by the existence or non-existence of a public program.

Domestic Education Comparisons

You've probably heard the old saws about America's school system falling perilously behind, our teenagers scarcely better than a bunch of Slovenian slackers while studious Singaporeans win the future. As Kevin Drum observes, it's not really true, American students have never tested best in the world, American education has been said to exist in a state of crisis since Sputnik (at least!) and though it's clear "that America does a terrible job of educating low-income students" it's less clear if "our low-income kids score worse than other countries' low-income kids? Or do we simply have more low-income kids?"

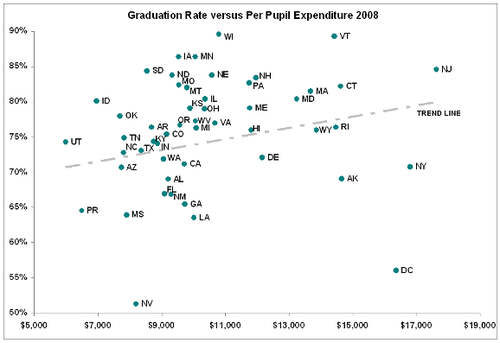

That's why I think it's generally more helpful to take advantage of the fact that America is a big country and that Americans are pretty familiar with the characteristics of its sub-units. Here's a chart Dana Goldstein posted recently:

I don't know what firm conclusions you can draw from that scatterplot, but it seems to be saying that within the United States of America some states are getting more value for their money than others. Very white states and low poverty states seem to do better, but even if you try to look at pretty similar states (New Jersey and Connecticut, Maine and New Hampshire) you see big differences.

Of course that particular data set has a lot of limitation. But CAP has a nifty interactive tool that lets you see a much richer range of information down to the district level. And what you see, over and over again, is that "it's complicated." You can adjust for all kinds of different things, and it invariably comes out to be the case that however you slice the demographics there's a very weak correlation between spending and student outcomes.

Our analysis showed that after accounting for factors outside a district's control, many high-spending districts posted limited outcomes. In Minnesota just 23 percent of the districts in the top third of spending were also among the top third in achievement. In Florida, only 17 percent of the state's highest-spending districts were also in the highest-achieving tier.

In high-spending districts, success often comes at significant cost. Consider Howard County School District in Maryland. Many consider the affluent district to be one of the best in the country, and a magazine recently heralded the district as an international academic "powerhouse." But after controlling for factors outside the district's control, the school system has one of the highest rates of perstudent expenditures in the state, spending over $1,600 more per student than the state average and almost $3,000 more than the national average.

There are two different possible takes on this. One is that there's something wrong with the way many of our school districts are run and that it makes sense to experiment with a range of different approaches. Another is that the obvious demographic controls are inadequate, and the real differences here aren't driven by anything that happens in the classroom but by some hidden student characteristics. If that's true, then suddenly the preferred conservative solution of arbitrary spending caps and cuts suddenly looks appealing. I don't believe that's true, and I don't believe that the people who sometimes claim to believe it's true really believe it themselves. If you look at how upper middle class professionals raise their own kids, it's clear that they think it matters what happens in a child's educational experience. And I think they're right. But if they're right, then the implication of this is that many American school districts need to change things up in significant ways.

Egypt Fact of the Day

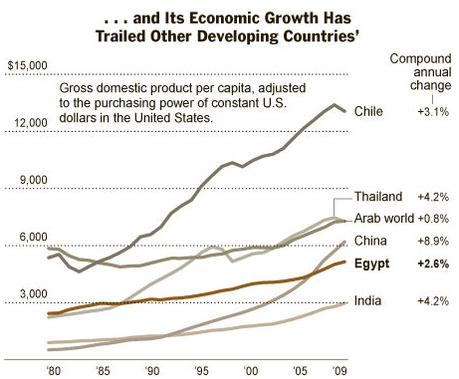

From David Leonhardt whose caught density equals growth fever:

Almost 50 percent of East Asians now live in cities. And Egypt? It is the only large country to have become less urban in the last 30 years, according to the World Bank.

Egypt's economic problem is quite profound. It's not rich enough for households to shrug off increases in the price of wheat and other commodity foodstuffs and it doesn't have the power to halt negative shocks to world food supply from climate change and poor management of water resources. Consequently as long as Egypt grows slower than the world average, it's going to be at risk for fall-behind immiseration every time the world has a bad harvest season. And it's not the only country in this boat.

Talking Great Stagnation

I talk about Tyler Cowen's The Great Stagnation on a new BHTV episode.

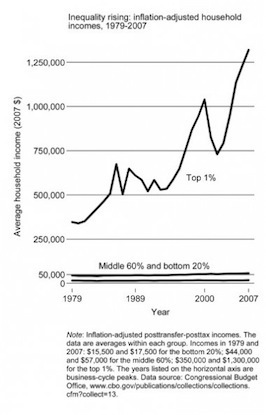

I think, however, that I may not have expressed my actual view of the situation very clearly. I think Cowen's argument that the stagnation in question is caused by a semi-mysterious technological slowdown is ultimately less persuasive than the circumstantial Krugman and Hacker/Pierson case that it's ultimately political in origin. But I think Winner Take All Politics often comes across as implying that the political problems here are very narrowly partisan in nature and could be easily remedied with more progressive taxation. The real issues, I think, are closer to Dean Baker's less conventional analysis in The Conservative Nanny State—substantial dysfunctions in the health care, finance, education, and housing sectors of the economy plus loopy intellectual property policy that are conspiring to make growth slower and more concentrated.

I'm all for more tax and transfer and better science, but I think we should be more ambitious in our goals and more searching in our quest for improvements.

You Don't Need A Balanced Budget To Shrink The Debt Level

One of the ironies of Washington is that the people who spend the most time talking about the budget deficit often have very little practical understanding of it. One example comes from my friend Dave Weigel's interview with Delaware Senator Chris Coons, who's positioning himself as a leading budget hawk:

"The framework that was laid out by the deficit commission, while I don't agree with everything they did, shows the direction I think we need to go in terms of scope," said Coons. "If we simply look at the 12 percent of the budget that's non-discretionary spending, we're never going to get there. I think we need to be doing the large work."

He had been bristling to ask OMB Director Jack Lew a question.

"Why do you think 3 percent of GDP is a sustainable deficit?" asked Coons. "Don't we need to get to a balanced budget, in order to get to the point where we're tackling the debt?"

The answer is that, no, you actually don't need to get to a balanced budget in order to tackle the debt. The country's debt is becoming less burdensome, which is to say any time GDP is growing faster than the debt. If debt growth is zero (balanced budget) or negative (surplus) that usually means fairly rapid debt-shrinkage. But given positive economic growth, modest budget deficits are completely consistent with reductions in the debt burden.

(Incidentally, I'm not as important or busy as Jack Lew and am available to any other senators who are having a hard time getting their phone calls returned).

Fair Competition Makes The Case for Assistance

Sallie James complains that "in their press releases, Senators Casey and Brown both alluded to the 'fact' that the TAA helps workers 'either get back to work or regain some measure of the financial security that has been stripped from them due to unfair foreign trade.'"

Indeed, I would say it's the very fact that a lot of people can lose jobs do to perfectly fair international competition that actually makes the case for financial assistance. If the problem was malfeasance of some kind, the right solution would be to halt the malfeasance. The main issue is that in a technologically and socially dynamic world, fair competition leads to people suffering economic hits through no fault of their own. This is one of several reasons why it's important to have public services and a social safety net. Even people who do everything right—acquire skills, work hard, etc.—can be subject to large and unpredictable negative shocks to their value as a worker. Halting all the possible sources of these shocks would be disastrous to economic growth. But refusing to acknowledge the reality and pervasiveness of this kind of misfortunate treats people unfairly and pushes political activity in the direction of rent-seeking.

February 15, 2011

Endgame

Taken almost all that I've got:

— Voters got mad about the economy and in exchange are getting a wave of radical anti-choice measures.

— Everything about Kennedy Fried Chicken is hilarious.

— "In Search of Productivity Gains in K-12 Education" and Mark Kleiman on the same.

— I'd really like to read the giant New Yorker piece on Scientology but I keep getting distracted by writing blog posts.

— David Mayhew is never wrong, but I have a suspicion that his new book may be wrong.

For the budget, Cat Stevens "The First Cut Is The Deepest".

The Second Term

(cc photo by kevindooley)

EI asks:

I was wondering: what is the historical track-record of second-termers when it comes to enacting far-reaching policy? My uninformed sense is that it's really in the first term, and the beginning of it at that, where the heavy lifting gets done, and that the second term is often where things go awry.

I think this is a mistake. An enormous amount of significant legislation passed in Lyndon Johnson's second term. As I wrote yesterday, the 1950 amendments to the Social Security Act in Truman's second term were extremely significant, though little-remembered today. And the Civil Rights Acts of 1957 and 1960 in Eisenhower's second term were also important. The 1986 tax reform was important, and I'd say the majority of the important legislation from the Clinton era came in the second term.

The real outlier here, I think, is the second Bush administration which resulting in almost shockingly little legislation. The 109th Congress of 2005-2006 worked the fewest days of any modern congress, passed very few bills, and its most important laws (bankruptcy reform and an energy bill) were terrible. And that was before the GOP lost its majorities. The issue here is that after trying and failing to storm Fort Social Security, the conservative coalition seems to have basically given up on doing anything. Now, though, it seems like Paul Ryan is ready to charge again at Social Security and/or Medicare.

The 401(k) Disaster

An offhand but important remark from Felix Salmon:

Just because you have a 401k plan does not, ipso facto, make you an investor. This is a serious problem with defined-contribution pensions in general: they place an onerous set of responsibilities onto individuals who are wholly unqualified to discharge them in a sensible manner. Already, such plans tend to have far too many choices, many of which are expensive long-only mutual funds which seem like a pretty bad idea for just about anybody. Trying to add alternative investments in private equity or hedge funds to the mix would almost certainly be disastrous — the dumb money coming in at just the wrong time, just like it always does.

I think this is a really underrated problem with the contemporary United States and a major policy error of the neoliberal age. It's bad for middle class workers who are having a share of our compensation siphoned away by value-subtracting financial managers, and it also seems to me to undermine corporate governance. How am I contributing to the management of the firms of which I am, through my 401(k), a partial owner? Well, not at all! Heck, I couldn't even tell you the name which firms I partially own.

The basic idea of Social Security—a slightly redistributive defined benefit pension with a capped contribution level—is actually a really good vision of how middle class people should pay for retirement.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers