Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2414

February 20, 2011

Labor Unions and Me

Ezra Klein's weekend question: "Almost forgot! Have you or anyone close to you belonged to a union? How did that change your impressions of organized labor in general?"

I'm generally speaking an out-of-touch pointy headed elite, but as it happens throughout my life my father has been a union member. Specifically, he's in the Writers' Guild of America a small (but important in its sector) AFL-CIO affiliated union. He's even been an official in the union.

The main thing I'd say I learned from that is about how difficult it is to maintain unionization gains in the context of a union-hostile environment. In television there's been a big move away from using unionized writers and unionized actors in favor of shows oriented around non-unionized "real people" as the performers and non-unionized "editors" and "producers" to create the storyline. The distinctions here are metaphysically questionable but they hold up legally, and the US policy environment makes them very difficult to fight. The way to organize "reality" TV, it seems to me, would be through secondary strikes. But that's illegal. The studios are, however, allowed to execute what amounts to secondary strikes in reverse in replace union-made scripted shows with with non-union "reality" ones. This not only directly weakens the land of labor in collective bargaining, but it sets up a dilemma. The capital of TV studios naturally flows to the most profitable sectors of television. So insofar as labor succeeds in extracting a larger share of the surplus in scripted programming, that merely accelerates the shift to non-scripted programming. Alternatively, labor can seek to slow the shift to the non-scripted sector by reducing its demands for workers to get a larger share of the surplus. Either way, the prognosis is bad unless it's actually feasible to unionize the non-union sector which under the Taft-Hartley legal regime it isn't.

This is structurally the same problem faced by the United Auto Workers vis-à-vis factories in "right to work" states. I think the classic postwar American dynamic of an economy with a large minority of the workforce unionized is fundamentally unstable. In the long-run the two equilibria are toward a non-union economy or else toward the Nordic model where virtually everyone is in a union. In the latter case, I think the unions become organizations of a more political character than anything else. In theory, Swedish labor unions could use their dominant labor market position to increase workers' compensation by making Swedish firms less profitable than non-Swedish ones, but that would be bad for everyone. What you get instead is a kind of Mirror Universe version of the Chamber of Commerce, a politically powerful institution interested in maximizing the income growth of the median Swede rather than the median Swedish CEO.

Separation of Teaching and Credentialing

Another thing to consider about college costs is the strange way that we've fused the instruction and credentialing functions. The supply of prestigious credential-bestowing institutions is necessarily constrained because that's what it means to be prestigious. But there's no reason to think that it's necessarily expensive to operate a prestigious credential-bestowing institution. MIT isn't prestigious because its TAs are unusually competent at grading problem sets. Teaching by contrast seems expensive to do properly but also in principle open to unlimited competition.

But right now a lot of our conventional practices are upside down. For example, Paul Krugman and Greg Mankiw are both high-profile economists attached to prestigious institutions (Princeton and Harvard) who both have introductory economics textbooks. One is a liberal and one is a conservative. Now suppose that instead of having competing economics textbooks they came together to collaborate on creating the Mankiw-Krugman Introduction to Economics Certificate. The MKIEC would be a test, basically, administered on regular dates and it would say "hey, these famous guys say people who get a good score on this know introductory economics." Of course you'd have a problem with regulatory and accreditation cartels. But even so, there could be some value. Personally, I sometimes need to admit in a slightly embarrassed tone that I've never actually taken an intro economics course. The best I can say is that I have read both the Krugman and the Mankiw textbooks and I think I understand the material well enough to be taken seriously by economics bloggers with PhDs and everything. But if I had a test blessed with the good housekeeping seal of approval of an ideologically diverse set of famous economists, that would have some value to me.

But what's more, if you could somehow persuade Harvard and Princeton to both start giving the MKIEC test to their own undergraduates the ball would really be rolling. Suddenly any institution in the country—an accredited college or otherwise—could compete on a level playing field with fancy ivy league schools in terms of teaching introductory economics. Then instead of a buch of institutions competing to recruit the most famous economists to teach their intro classes or competing to recruit the students with the highest SAT scores, you'd actually be competing to deliver skills in a cost-effective manner because the prestige factor has been outsourced to MKIEC.

February 19, 2011

Montana Considers Bill To Repeal Science

Cute:

Republican Rep. Joe Read of Ronan aims to pass a law that says global warming is a natural occurrence that "is beneficial to the welfare and business climate of Montana."

This seems like fruitful territory. Imagine what could be achieved by simply passing laws that say tax cuts raise revenue and defense spending doesn't count as spending.

Disrupting College

As Tyler Cowen suggests my view of the college cost conundrum is that this is likely to be tackled initially at the low end. As Mark Kleiman says, to solve the Baumol effect problem in education you'd basically need to start offering something that doesn't at all look like our canonical image of a college. Incremental change in what the University of Michigan does won't cut it, you'd need a qualitatively different kind of institution. But to create something that's qualitatively different from, but as good as, and also cheaper than the University of Michigan would be a mind-boggling logistical and regulatory challenge.

What you could plausibly hope to see happen is the creation of an institution of higher education that's (a) much worse than the University of Michigan, (b) better than nothing, (c) radically cheaper than the University of Michigan, and (d) scalable. Then you could imagine a model like that moving incrementally up the quality ladder. CAP put out an interesting paper from Clayton M. Christensen, Michael B. Horn, Louis Soares, and Louis Caldera laying out some of the fundamentals here.

I know a lot of people, especially people working in or around academia, find this kind of talk unpleasant. But people thinking about education really do need to confront the Baumol problem. Around the margin, government subsidies can and should step in to make college affordable to talented students from poor families. But tuition subsidies as a share of GDP can't just rise every year. Either a college education will turn over time into something that only a narrow elite can afford, or else our idea of what "a college education" looks like has to transform into something with a lower cost structure and more scalability. Even people who do focus on the cost-side like Matthew Kahn here often seem to me to be looking too much at the level rather than the shape of the curve. If tuition leapt 50% then stayed flat as a share of income, that would be fine; 5% a year forever isn't sustainable.

Collective Bargaining Map

I'd been hoping to find a map of states' collective bargaining policies and Josh Marshall found one:

As with a lot of things in American life, it's all tied up with region, history, and political culture. Plenty of states seem to manage to have budget crises much severe than Wisconsin's with less union-friendly legal regimes.

Cutting $100 Billion

My colleagues Michael Ettlinger and Michael Linden have put together a useful interactive tool that lets you try your own hand at cutting $100 billion out of the domestic discretionary budget. It's, um, hard! Especially if you take the view that the country shouldn't eat its seed corn by slashing research and infrastructure spending, you basically have no choice but to hammer the poor and pare back all kinds of regulatory agencies and just kind of hope that doesn't make it too easy for people to get away with malfeasance.

Of course I suspect that to many conservatives making it easier to get away with malfeasance is feature and not a bug.

Impossible Tax Swaps

GS writes:

On 'grand bargains' and regressive cuts…

Doubling the gas tax would bring an additional 20-30 billion in revenue… it would also have a significantly positive environmental impact.

Why not trade a 20-30 billion tax increase for a 20-30 billion tax decrease on, for example, FICA?

That's easy—status quo bias. This is good policy, but like anything that that swaps FICA for anything it's bad for retired people. And like anything that begins to dismantle America's sprawl-driven industrial policy it's bad for people who drive a more than mean amount and auto firms that sell lots of SUVs and pickup trucks. What's more, some people would be disquieted about the potential destabilization of dedicated funding streams for Social Security and transportation. In a political system that permits thousands of ways to kill a proposal, the change won't be made.

In America, it's very difficult for policy to make modest shifts. Instead, the vast majority of the time nothing happens. Then sometimes you get big shifts. I've learned recently that in technical terms the policy change curve has a leptokurtic rather than normal distribution.

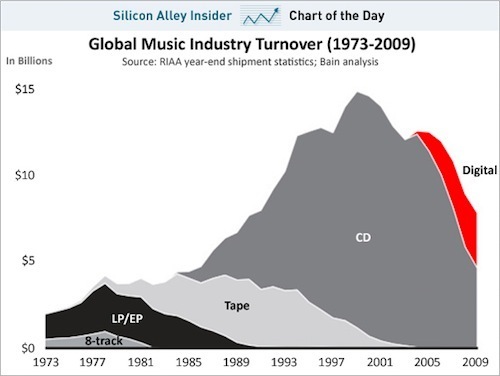

The Death of The Recordings-Sale Industry

Via Brad DeLong a striking chart that's mislabeled "The Death Of The Music Industry":

This measures something that's both larger and smaller than the "music" industry. The newspaper industry isn't the words industry or even the news industry. People still listen to music. People still play music. People who play music even still earn money. But the business of selling recordings of music is shrinking. Which, of course, is exactly what ought to be happening to it. Distributing a digital copy of an album to a person's computer is much cheaper than manufacturing and distributing a physical CD to a retail store. In a competitive market, the price of a widget ought to approximate the marginal cost of producing an additional widget. That's one reason why this blog is free to read. Thanks to copyright, a recordings-seller does have some level of market power to allow him to seek monopoly rents. But there's a pretty high degree of substitutability between different songs, so the competition is still pretty intense and the prices are low.

This is one reason why I would discourage bands from trying to underprice tickets at their own shows as a reward to fans. Since digital copies of recordings are non-rival and basically free to make, any non-zero sale price entails some deadweight loss. And since concert tickets are necessarily scarce, any sub-market price entails some deadweight loss. The optimal strategy for a popular band that wants to do something nice is market pricing for concert tickets, plus free recordings. Or even better, you could release your records into the public domain.

February 18, 2011

Endgame

Like a train on a track:

— The ECB's price stability cartoon.

— Interesting corporate income tax reform idea.

— I don't mind ecommerce killing off sales taxes . . . eventually we need to switch to carbon tax.

— Mitt Romney would very much like to be president.

— Turks and Caicos: what went wrong?

Florence and the Machine, "Dog Days Are Over"

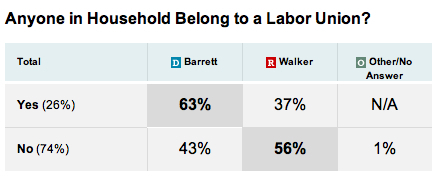

Union Member Voting Behavior

I thought I'd look up how union members voted in the 2010 Wisconsin midterms. The exit polls didn't actually provided the data, but they did ask about whether you live in a union household. Not surprisingly, union households like Democrats:

That's a strong showing for Barrett but not nearly as strong as, say, his pull of 87 percent of the African-American vote. Had unions delivered 70 percent of the union household vote to Barrett, he would have won. Russ Feingold pulled 59 percent of the union household vote in his failed re-election bid. Nationally, 61 percent of union household voters pulled the lever for a House Democrat in 2010.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers