Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2411

February 23, 2011

The High Price of Objectivity

(cc photo by kevin dooley)

Dana Goldstein attempts to defend "last in, first out" layoff policies for public school teachers:

In education, reasonable people have been disagreeing, for decades and decades, about how to define and measure good teaching. LIFO has become standard practice because in the absence of such agreement, it has one great advantage: LIFO can be applied completely objectively.

Life is full of situations that demand you to make decisions under conditions of uncertainty. In almost all cases, the right thing to do is to try your best not to simply give up. Note that since teacher compensation costs increase as a function of experience, LIFO is actually worse than the equally objective practice of firing teachers at random. LIFO maximizes layoffs relative to financial targets. Doing layoffs by lottery would allow districts to fire fewer teachers.

But of course doing layoffs by lottery would be a pretty silly way to run an organization. Adopting any criteria, no matter how imperfect or contestable, that had any correlation to performance whatsoever would be an improvement over random firing. Measuring job performance is hard in any field, and it's hard in teaching. But is it so hard that we really couldn't do better than firing people at random? Note that if it really is completely impossible to obtain actionable information about teacher quality, then suddenly the case for forcing teachers to swallow dramatic pay cuts looks pretty strong. I don't buy it. I think hiring good teachers is important, and part of that is thinking that it's possible to obtain information about which teachers are the good ones. But if you seriously think we can't, then we should at least shift to random firing.

Switching on DOMA

Seems like a good idea to me for the Obama administration to stop arguing for the Defense of Marriage Act's constitutionality. They even have a lawyerly-sounding reason for the switch!

Pro-Growth Climate Economics

Dave Roberts' latest efforts on disputes within the community of people who accept that climate change is real and undesirable has a wise conclusion:

This exercise is clarifying, I think, but it shouldn't obscure the fact that virtually every serious economist recommends action. Nordhaus puts it well: "While there is debate about whether the 'right' number for a carbon price is $10, $20 or $100, the global average today is close to $1 and moving nowhere. So we have a long, long way to go before we even enter the range of debate."

There's no excuse for inaction.

I think it can't be emphasized enough that there are lots of early-stage efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions that should be uncontroversially growth boosting. Shifting the tax burden off labor income and onto pollution is pro-growth tax policy, completely aside from the environmental benefits. And one could say the same about congestion pricing for roads, relaxing restrictions on high-density real estate development, and curbing subsidies to fossil fuel producers. Had we already done all those things it would then be interesting to debate the ethics of the tradeoffs between short-term growth and longer-term climate devastation entailed by further measures. But that's a long way from where we are now.

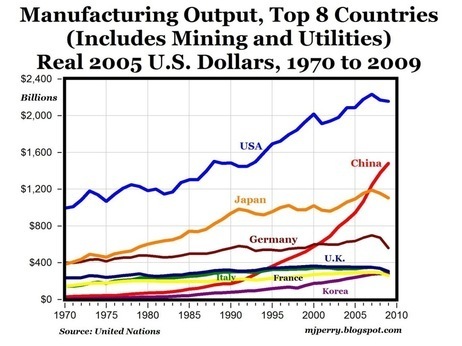

"Making Things"

Brian Beutler quotes Senator Sherrod Brown:

"The President's done more on manufacturing than his predecessors, but not nearly enough," Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH) told me in an interview Friday. "That needs a real strategy on making things. We ought to make things in this country. And it's a strategy on a different trade policy, a different tax policy, an emphasis on working with small manufacturers."

I continue to disagree. Obviously, it's not viable for the United States to be a country in which no things are made. But the reality is that lots of products are manufactured in America:

What's declined isn't manufacturing output, it's manufacturing employment. And I think it's important to understand that there's real arbitrariness in how manufacturing employment is defined. The security guard at a factory has a manufacturing job if he's employed directly by the factory, but not if he's employed by security firm that has a contract with the factory. Obviously, though, he has basically the same job ("security guard") in either case, and it's a job that has a lot in common with the security guard at the office building. If your job is to turn fresh green beans into canned green beans, you're manufacturing. If your job is to turn fresh green beans into someone's dinner, then you're not manufacturing. But if people switch away from canned green beans to more restaurant meals, that's almost certainly a sign of progress.

That neoliberal claptrap aside, I bring this up in part because I think understanding these dynamics is crucial to mounting a defense of the public sector. As we're able to produce more material goods with fewer people, that ought to lead not only to more chefs and yoga instructors and private security guards but also more preschool teachers and cops and home health aides. There's an argument out there that "we can't afford" the larger public sector that's currently projected for the future. But we can afford it, and the fact that in the future we won't need as many manufacturing workers to have all the manufactured goods we need is a big part of the reason.

The Decline of the Strike

Via Matt Stoller's Twitter feed:

Of course ups and downs in the volume of strikes can mean more than one thing. The strike spike in the 70s seems to me to have been driven primarily by real negative shocks to the economy that forced capital and labor to re-divide the surplus. Either way, the point is that significant labor action hasn't been an important part of the experience of most people my age. But of course personal experience will vary in this regard—my dad's been on strike twice in my lifetime.

Bait and Switch

Must read piece from Tim Fernholz:

The state's entire budget shortfall for this year — the reason that Walker has said he must push through immediate cuts — would be covered by the governor's relatively uncontroversial proposal to restructure the state's debt. By contrast, the proposals that have kicked up a firestorm, especially his call to curtail the collective-bargaining rights of the state's public-employees, wouldn't save any money this year.

I think there's something to be said for the idea that you don't want to let a good crisis go to waste. But that's what's happening here. Scott Walker wants to crush the political power of a subset of Wisconsin public sector unions, so he's proposed a bill to do that. It has nothing to do with the short-term fiscal crunch that's being used as a pretext.

Partisan Balance

Any time you read something David Mayhew has written, you end up learning something. His latest book, Partisan Balance: Why Political Parties Don't Kill the U.S. Constitutional System is no exception to that rule. Nevertheless, it's still a bit of a strange book because it's not entirely clear to me why he thinks his thesis is so reassuring.

The central claim of the book is that American political institutions aren't systematically biased against one political party or the other. Examining the Truman to Bush era, he shows that thanks to the "packing" of liberals into super-partisan urban districts, the median House district is about one percentage point less Democratic than the country as a whole. The Senate is a bit more GOP leaning, but only slightly so. He shows that Democratic and Republican presidents have had equal (and large) amounts of trouble getting congress to go along with their ideas. He shows that both the House and the Senate have played obstructionist roles at different times and in roughly equal measure. He reminds us that there have been times when the Senate was more liberal than the House as well as vice versa.

This is all good to know, and I learned a lot of fascinating political history along the way. But the natural interpretation seems to me to be that America's political parties are very good at adapting to institutional realities. That's interesting, but it doesn't carry much justificatory power. It seems to me that if we made it illegal for women to vote, the party system would adjust to the shock. But it would still be wrong, and would still have important consequences for people's lives. Presidents try not to put obviously doomed items on the agenda, and good for them. But that leaves open the question that important topics are being kept off the agenda.

Bottom line: Good book, but I wouldn't make this your first Mayhew if you haven't read any of his other books.

Enlightened Despots

Chris Bertram proposes: "The Emir of Qatar may be a despot, but for Al Jazeera alone he could be winning a Frederick the Great prize as the most enlightened one of recent decades."

An interesting idea. I'm heading to a meeting with the program director for Al Jazeera English a bit later this morning and it certainly seems to me that for all the Twitter/Facebook hype, the key information technology intervention here has been Al Jazeera and the rise of an Arab public sphere. Marc Lynch's Voices of the New Arab Public: Iraq, al-Jazeera, and Middle East Politics Today was way ahead of the curve on this, but the publisher seems to be asking an extortionate price to read the book.

I think the idea of a Frederick The Great Prize has a lot of promise. Give it out maybe once a decade? Previous winners could include Lee Kwan Yew for his visionary implementation of congestion pricing and perhaps Mikhail Gorbachev.

February 22, 2011

Endgame

Fog rolling down behind the mountains:

— Politics is undermining the recovery.

— The Ryan McNeely Blog has launched.

— Where are all the good men?

— This is where the women writers are.

— 61 percent oppose limits on union bargaining.

PJ Harvey, "The Last Living Rose"

Trade Policy In 17th Century North America

From Alan Taylor's American Colonies: The Settling of North America:

Ironically, the French also came to depend upon Iroquois hostility as a barrier that kept the northern Indians from traveling south to trade with the Dutch. The French recognized that they could not compete with the quality, quantity, or price of the Dutch trade goods. Therefore, a prolonged peace with the Iroquois would tempt northern Indians to carry their furs to Fort Orange for shipment to Amsterdam—to the detriment of Quebec and Paris. The French could ill afford friendship with the Iroquois, although they paid a heavy price in death and destruction for their enmity. The Five Nation Iroquois became equally ambivalent about peace with the French. The Iroquois usually preferred to steal furs from their northern enemies to take to Fort Orange, rather than permit them as friends a free passage to the Dutch traders. Because the northern Indians possessed better furs, they would, in the event of peace, become the preferred clients and customers of the Dutch, to the detriment of the Iroquois. As inferior suppliers of furs, the Iroquois had a perverse common interest with the French, an inferior source of manufactured goods. They both tacitly worked to keep apart the best suppliers of furs (the northern Indians) and of manufactures (the Dutch).

And today France is a rich country thanks to all the good middle class jobs this Iroquois protectionism helped save.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers