Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2387

March 16, 2011

Manhattan Population History

I don't want to say too much about the debate over increased density in Manhattan because, again, ebook proposal. But one reality check on this whole subject is to note that the population of Manhattan 100 years ago at 2,331,542 people. It then hit a low of 1,428,285 in 1980 and has since then risen back up to 1,629,054.

Back in 1910 there were only 92,228,496 people in the United States. Since that time, the population of the country has more than tripled to 308,745,538. And if you look at Manhattan real estate prices, it's hardly as if population decline in Manhattan has been driven by a lack of demand for Manhattan housing. Back around 1981 when I was born, things were different. The population of the island was shrinking and large swathes of Manhattan were cheap places to live thanks to the large existing housing stock and the high crime.

Property Rights And the Kochs

If I walked over to David Koch's lawn and tore up all the grass, he'd probably feel that the basic principles of a free market society require me to be punished. After all, that's his property. And then there's what happens when the Kochs want to pollute someone else's river:

The complaint alleges that a Georgia-Pacific paper mill on the Coffee Creek in Arkansas – owned by the billionaire Koch Brothers -emits 45 million gallons of paper mill waste including hazardous materials like ammonia, chloride, and mercury each day.

Coffee Creek then flows into Louisiana's Ouachita River where the pollutants have left the formerly pristine water speckled with odorous foam, slime and black pockets of water, said Jerry Johnson, who has been visiting the Ouachita River for 35 years.

"People used to swim in it," said Johnson, who now lives along the river. "In the summertime, it was the place to go."

But Johnson said the number of visitors has dwindled as the river conditions continued to grow worse, preventing the area from reaching its full economic potential as a vacation destination. The pollution is so bad it has kept Johnson from fishing in the river.

And yet somehow the coalition merchants of the contemporary right, financed by the Kochs and other industrialists, have constructed a conception of free markets and property rights such that trying to stop them from wrecking Ouachita River constitutes a defense of those things.

Green Chernobyl

Kevin Drum tries to drive home exactly how counterintuitive it is that big cities are environmentally friendly:

Here's the thing: my guess is that virtually nobody in the country thinks that cities are greener places than towns or suburbs. And by "virtually nobody," I mean maybe a few percent tops. For most people, it's wildly counterintuitive on all sorts of levels to think of big, dirty, crowded, urban areas as "green." It just doesn't compute.

I'd been familiar with this result for a long time so it no longer feels counterintuitive to me. But I found myself reshocked by the flipside of this recently while reading up on nuclear catastrophes. It turns out that the portion of countryside most affected by radioactive fallout from the Chernobyl disaster is something of a thriving wildlife refuge. It's not the best wildlife refuge in the world—there's all the radiation to deal with—but compared to the average spot on the land area of Europe it's extremely friendly to wildlife. And that's not despite the radiation, it's because of it. All the radiation keeps the people away, and people are terrible for wildlife.

The point isn't that we should welcome radioactive fallout. The point is just that there are major ecological benefits of true wilderness—of places that aren't sliced up by roads and terraformed for human convenience. And the flipside of crowded urban areas is that leaves more genuinely vacant land. Something like a lawn or a golf course looks quite lush and green, but people don't want wolves on their lawn. By contrast, "species not seen for decades, such as the lynx and eagle owl, began to return" to the Chernobyl area once the people left.

The Nuclear Stakes

As I said before, I don't want to be the pro-nuclear guy in the energy debate, but this kind of thing makes me nervous:

In the most dramatic move, German Chancellor Angela Merkel announced Tuesday that all seven of the country's nuclear power plants built before 1980 would be shut down, at least for now, as safety checks are conducted. The decision came one day after the government, facing strong public opposition to nuclear energy ahead of upcoming regional elections, suspended plans to extend the life of its aging plants.

Switzerland, with five reactors, announced Monday that it would freeze plans to build or replace nuclear power plants, and Austria called for new stress tests on plants across Europe.

Some people responded to my earlier posts by saying "sure, fossil fuels are terrible, but that doesn't mean nuclear is good—we need real clean energy." And I agree, we do need real clean energy. And if what was happening here is that the German government was announcing a visionary plan to transform Europe to a renewable energy utopia, I'd be clapping. But if what actually happens is just that people say "yikes!" and clamp down on nuclear then that really just further entrenches the status quo. As Kevin Drum said the other day what needs to happen is for us to start pricing the externalities of fossil fuel use. With that done, I have no particular inclination to engage in further nuclear cheerleading. But reacting to Japan by burning more coal and pumping more oil isn't any kind of progress.

The Indecisive Midwest

Jon Chait watches the polls sway back and forth around the Great Lakes:

[I]t's pretty interesting that Republican governor John Kasich is already incredibly unpopular in Ohio, running 15 percentage points behind Ted Strickland, who he narrowly beat last November. Meanwhile, several Wisconsin state Senators look to be getting pulled down in the Scott Walker undertow. The big picture is that the Republican Party was deeply discredited by the end of the Bush administration. Then you had Democrats running the government everywhere at the moment of the worst economic crisis in 70 years, so they managed to win power in a bunch of states. But this fact seems only to be reminding people why they hated Republicans in the first place.

There's no question that this is right. Nor is there any question that some measure of "overreach," first by congressional Democrats and then by state-level Republicans, is driving this.

But it does seem to me that the political see-saw is swinging especially violently in this region, even as this broad economic story applies everywhere. I can't help but wonder if this doesn't reflect the fast that the Midwest seems to be in a state of pretty severe relative decline vis-à-vis the nation as a whole. Broadly speaking, we're seeing very rapid population growth in key sunbelt areas. Then in Boston-Washington corridor and Pacific Northwest we've seen housing become very expensive, which has tamped down population growth but indicates that demand is present. But states like Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, and Wisconsin have neither a fast-growing metro area like Houston nor a "nobody goes there any more, it's too crowded" city like San Francisco. You could easily imagine this kind of situation leading to an unusual degree of voter fickleness and persistent dissatisfaction with all options.

Tea and Urbanism

Ed Glaeser says the tea party should take on big government initiatives that hurt cities:

Big cities are not typically Tea Party territory, but if the new Republican members of Congress apply their libertarian principles assiduously to a few key federal policies, they could do much for urban America. Residents of dense downtowns should urge Tea Partiers to take up the fight against socially engineered suburbia through federal homeownership subsidies and sprawl-inducing federal highway spending. [...]

Good libertarians might ask why the federal government has any business promoting particular lifestyle choices, like homeownership. Shouldn't Americans be free to choose where and how to live without the government prodding them to buy and borrow? The federal home mortgage interest deduction is public paternalism at its worst. The mortgage deduction made the federal government the silent, subsidizing partner of the millions who lost billions in the recent housing crash. The subsidy encourages Americans to borrow as much as possible to bet on housing.

It would be easy (and, indeed, appropriate) to dismiss this as a hopelessly naive read of American politics. But if you think of pundits as coalition merchants, the point is that this represents as possible future configuration of the American issue landscape. The issue here is that, realistically, advocates for pro-urban policies are mostly going to be people who live in big cities, which is to say people who identify with the left of American politics. Urging older socially conservative whites who don't like taxes ("tea parties") to also support pro-urban ideas on the grounds that this is a kind of opposition to big government seems unlikely to pay off. But you could imagine some of the wealthy elites with a quasi-principled interest in free market ideas funding efforts along these lines, with the younger, disproportionately minority urban demographic as the target audience. And, yes, that is a long-winded way of saying David Koch should give me huge sums of money to complain about zoning.

John Boehner's Dilemma

Brian Beutler's reporting/analysis of John Boehner's growing difficulty keeping his caucus together is excellent:

But Tuesday's outcome was nonetheless a mixed one for Boehner. It illustrated a reality he'd hoped to escape — that a large chunk of his caucus won't vote with him if he compromises. Indeed, the 54 Republicans who voted against the stop-gap legislation put him in an unenviable box: Either he kowtows to his right flank, and pushes initiatives that can't pass in the Senate; or he abandons them, as Sen. Chuck Schumer (D-NY) has suggested, and passes consensus legislation. The latter option, however, would require significant concessions to win Democratic votes, and further delegitimize himself with the Tea Party base.

If he chooses option (b), he will need Democratic votes. And that would abruptly flip the dynamic on Capitol Hill, where Republicans have been riding high since they trounced Democrats in the November elections.

If he chooses option (a) — if he and his party don't back off their pitched demand to fundamentally reshape the U.S. government — the consequences they'd hope to avoid — shutdowns and worse — will become all but inevitable.

I note that Boehner really has no one but himself to blame for this. The outcome of the 2010 midterms was the a Democratic President is in the White House, there's a Democratic majority in the US Senate, and a Republican majority in the US House of Representatives. If you simply count, that's two out of three for Democrats, meaning a Democrat-leaning policy agenda. Specifically the logic of the situation was that the way to avoid gridlock is for the the President to use his agenda-setting powers to focus attention on issues (like trade and K-12 education) where the Obama position is at odds with substantial elements of the Democratic base.

But instead Boehner himself vastly oversold the implications of the 2010 election and tried to say that he should be setting the agenda. That's natural, everyone likes to seize power for themselves. But the math just isn't there. A House Speaker faced with an opposition president and an opposition majority in the Senate has no real way to drive the political process. Any attempt to do so can only lead to gridlock, and gridlock in the current context means government shutdowns that Boehner wants to avoid.

Stuff White People Like: Republicans

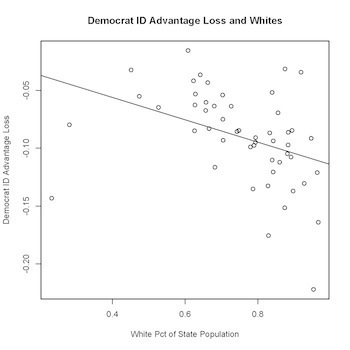

A good series of charts by Lee Drutman shows that one of the best predictors of declining Democratic partisan ID between 2008 and 2010 is the number of white people:

I used to hold to the view that the growing non-white share of the electorate would, over time, tip elections to Democrats. I now think the system will remain near equilibrium and what we'll instead see is white voters growing more Republican as Democrats are more and more seen as the party of non-whites. Mississippi and Arizona, after all, have very large minority votes but they're hardly hotbeds of liberalism. Instead they're hotbeds of very conservative white people. This does mean, however, that politics will become even more abstracted away from "the issues" and questions of identity will become even more central.

Learning to Love Traffic Metrics

I read James Fallows' piece "Learning to Love the (Shallow, Divisive, Unreliable) New Media" on the plane yesterday, and thought it was pretty great. He offers a tour d'horizon of the emerging economics of the media business, discusses problems, delivers a little much-needed Real Talk about the good old days, and raises some hopes for the future.

But there's one aspect of this where I wanted to press harder for webtimism than Fallows does. That's specifically on the merits of a system where you can actually tell who's reading your articles. Fallows emphasizes, citing Nick Denton, that in a competitive metric-rich landscape your incentives tend to point away from highbrow "important" stuff toward lowbrow mush:

Of course, Denton was omitting good-for-you, public-service-style stories for outrageous effect. In my first "interview" with him for this story, conducted over the course of nearly an hour through an instant-message exchange, he said that a market-minded approach like his would solve the business problem of journalism—but only for "a certain kind of journalism." It worked perfectly, he said, for topics like those his sites covered: gossip, technology, sex talk, and so on. And then, as an aside: "But not the worthy topics. Nobody wants to eat the boring vegetables. Nor does anyone want to pay [via advertising] to encourage people to eat their vegetables."

Sad. And to a large extent true. But the thing that I think journalists sometimes forget is that the point of writing on worthy topics is presumably to get people to read stories on worthy topics. In the print world, I think people got too complacent about the idea of reporting out a worthy story, plopping it on page A3, and forgetting about it. Was anyone actually reading that story? It's not clear to me that they were. On the web if you want people to read worthy journalism it's made clear that this is actually a two-step process. First you have to produce the worthy content, and then you have to get someone to read the worthy content. That's a challenge, but it's a challenge those of us interested in writing on subjects we think are important ought to welcome and attempt to meet.

That may mean that people who write on worthy subjects earn less, long-term, than people who write about other things. But at the same time, it's more pleasant to do meaningful work so why shouldn't that be the case? And part of what it means is that people in the "writing about important things" business need to roll up our sleeves and try harder to make our output compelling to people. If an article about the school board falls in the middle of the wilderness and nobody reads it, it doesn't actually make an impact.

The Incapacitated State

I got a chance to talk to some Arizona state legislators from both parties yesterday afternoon and one thing even a very cursory chat drives home is the fairly disastrous consequences of some populist conceits about how a legislature should be organized. Specifically, the Arizona legislature combines low salary for members, short legislative sessions, term limits, and very limited staff (one secretary for every two state reps). This is all somehow supposed to keep representatives close to the people or prevent them from entrenching power, but in practice it amounts to a kind of government by lobbyist

After all, some of these issues are hard. And legislative procedure is hard. If at any given time a huge proportion of members are freshmen just learning the ropes of the institution and nobody has any time to consider the issues or staff to do research for them, who else are you going to turn to. Pondering the situation really drives home the "Lobbying As Legislative Subsidy" (PDF) model of what the industry is really about. Members need to take positions on the issues and speak about them to the press and to constituents. And without adequate staff or experience, they naturally end up outsourcing a lot of this work to other people—the dread special interests. And since "raise my salary and give me a bigger staff budget and repeal my term limits" is just about the most toxic political proposal I can imagine, there doesn't seem to be any way out of it.

But this is something to keep in mind in the federal context when you hear about how this or that area of policy should be left up to the states. However unimpressed you may be by the wisdom of the United States Congress, it's very difficult for me to think up complicated issues where pushing the issue down to under-resourced state legislators is likely to radically improve policymaking.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers