Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2390

March 14, 2011

Commerce Cabinet Crisis XV: Luthor Hodges

Luther Hodges grew up in North Caroline, graduated from UNC at the age of 17, and went to work for Carolina Cotton and Woolen Mills, continuing his tenure there after the firm's acquisition by Marshall Fields. He was a civic-minded kind of businessman who founded a local branch of the rotary club in 1923. By the 1940s he emerged as a local notable and was appointed to the state Board of Education and also to the Highway Commission. In 1944 he was appointed to the Office of Price Administration, an exercise in wartime socialism. In 1952, he became Lieutenant Governor of North Carolina, and then ascended to the governorship in upon the death of William B. Umstead in 1954.

As governor, he steered what counted at the time as a moderate course on racial issues. Specifically, as an alternative to directly resisting desegregation orders, his administration offered vouchers to families assigned to un-segregated schools and permitted localities to shut down their school system entirely by majority vote. His administration also inaugurated the Research Park that's done an enormous amount to lay the foundations for North Carolina's later success. At the time, North Carolina only allowed governors to serve one term, so by the time Hodges stepped down after winning re-election he was the state's longest-serving governor. Then in 1960, JFK won the presidency, carrying the state of North Carolina even while doing unusually poorly for a Democrat in the south. A racially moderate (relatively speaking) white southern governor with a reputation as a pragmatic businessman was just thing to add to the team so Hodges was a solid choice as Commerce Secretary, in which capacity he "had less influence than other members of the cabinet, serving more as a supporter and defender than as an architect of administration policies". Relative to other commerce secretaries, however, his tenure was relatively eventful as his department was charged with implementation of Area Redevelopment Act grants, an important New Frontier program later utterly overshadowed by LBJ's war on poverty.

Hodges resigned in 1964, went back to North Carolina, and ran the Research Triangle Foundation which seems to have worked out very well. All in all, if we're really fated to have a renaissance of explicit industrial policy in America, we're going to need more people like Luther Hodges.

Is Mississippi Too Much of a Dysfunctional Backwater For Haley Barbour to Become President?

The last time a subset of the American people voted to make a Mississippian President, the Mississippian in question was Jefferson Davis and he was President of the Confederate States of America. Liz Sidoti's coverage of current Governor Haley Barbour's all-but-announcement of a presidential campaign suggests there may be something about that state that stands in his way:

Trying to draw a contrast, the two-term Republican governor also boasted of his own record on economic growth and job creation in Mississippi, a state that has long been ranked at the bottom for personal income and education. "We still have more to do in Mississippi. But we have made great progress and are laying a foundation for the future," Barbour said. [...]

"What I learned as governor of Mississippi is that 'winning the future' doesn't start in Washington, D.C.," Barbour said, a swipe at the White House's latest slogan. "It won't be accomplished through government boondoggles like taxpayer-subsidized high-speed rail or other pet projects. It can't be achieved by having government take control of our automakers, financial sector, health care system and energy industry. [...]

Broken down by state, Mississippi had the highest share of poor people, at 23.1 percent, according to rough calculations by the Census Bureau in 2010. The median annual income is around $36,000 and 18 percent of its population has no health insurance.

Low human development indicators didn't stop Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton from winning in 1992, and my generic assumption is that this sort of thing doesn't actually matter much in a general election. But there's not a ton of precedent for it. Arkansas wasn't a very high-performing state, but it's a conservative one so Clinton was playing against type. Michael Dukakis and George W Bush were governors of stereotypically left-wing and right-wing states, but Massachusetts and Texas are both very successful states in their own ways. To nominate a right-wing politician from a state that's a byword for the failures of conservative governance would be pretty odd, especially when there's an orthodox conservative governor of Minnesota on offer as an alternative. But, hey, weird things happen. Back in 2008, Democrats went with the inexperienced black guy with a funny name.

Punditry as a Vocation

Frank Rich's humble and intelligent farewell column on the promise and peril of political punditry put me in the mind of research from Georgetown's Hans Noel that I was recently shown. He reveals, somewhat to my surprise, that political pundits appear to have a quantifiable impact on American politics. A number of his papers get at this (and I think a book will be forthcoming) but "Listening to the Coalition Merchants: Measuring the Intellectual Influence of Academic Scribblers" speaks most clearly to this issue:

Following Converse's advice that ideology is the product of a "creative synthesis," conducted by a narrow group of intellectuals, this paper reports on attempts to study ideology at its point of creation. I develop a measure of ideology expressed among pundits, based on coded opinion pieces in magazines and newspapers from 1830 to 1990. I use this measure to test the impact of ideas on party coalitions. I argue that ideologies, as created by intellectuals, strongly influence the coalitions that party leaders advance. In three cases – the realignment on slavery before the Civil War, the Civil Rights realignment in the mid-20th century, and the party change on abortion more recently – there is evidence that intellectuals reorganize the issues before parties realign around them. This evidence suggests that the patterns of "what goes with what" that intellectuals design have an impact on the nature of political cleavages.

In other words, pundits don't do much to tilt the balance on the high-stakes issues of the day. But we do help define the congressional landscape of tomorrow by influencing ideas about how the different issues fit together. So I guess I should be more explicit about this! People ought to support progressive taxation and upzoning to support denser land use and marriage equality for gay couples and reform of intellectual property law and taxation of polluters and others who consume our common natural resources while welcoming immigrants as contributing to the economic and cultural vitality of the country. Plus—less war.

Nukes Versus Hydrocarbons

(cc photo by Eurapart)

I'm with Will Saletan on this: "let's not block construction indefinitely while we go on mindlessly pumping oil. Because nuclear energy, for all its risks, is safer."

The significant safety risks associated with coal and with oil and with natural gas and with nuclear power are a good reason to promote the use of clean solar and wind power. But I worry that if you simply increase the burden on nuclear power without doing anything else to change the energy dynamic in America then what you're really doing is promoting fossil fuels. So ask yourself how resilient the alternatives would be in response to a 8.9 earthquake and a tsunami. We're currently told that the death toll in Japan will be at least 10,000 people of whom approximately zero seem to have perished in nuclear accidents. What happens when a tsunami hits an offshore drilling platform or a natural gas pipeline? What happens to a coal mine in an earthquake? How much environmental damage is playing out in Japan right now because of gasoline from cars pushed around? The main lesson is "try not to put critical infrastructure near a fault line" but Japan is an earthquakey country, so what are they really supposed to do about this?

I don't really want to be the nuclear apologist guy. I think of myself as a clean energy guy. I'm an energy efficiency guy. But what I'm definitely not is a fossil fuel guy. And you can't make sense of the safety concerns around electricity generation unless you put the nuclear risks in some kind of context.

Movie Theaters Looking For Menu Labeling Loophole

Had it been offered as a freestanding bill, Rep Rosa DeLauro's measure to implement a nationwide calorie menu labeling requirement would have been a very important and very significant issue all on its own. Instead, it got little attention as a component of the Affordable Care Act. But it has the potential to really help consumers meet their goals. Of course it also has the potential to make little difference to people's behavior. But when I read Jeff Young on movie theaters' desperate search for a loophole that would exempt them from the rule, I draw the conclusion that the people who know the industry best think it really will make a difference:

Movie theaters and grocery stores are lobbying the Food and Drug Administration to avoid the proposed regulation. Theater chains led by Tennessee-based Regal Entertainment Group generate as much as one- third of their annual revenue from concessions. Congress didn't mention theaters in the law and the idea of regulating them never came up at legislative hearings, said Patrick Corcoran, a spokesman for the National Association of Theatre Owners, a trade group. [...] Movie theater chains were supposed to be targeted by the mandate, said Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-Conn.), who sponsored a food-labeling bill in the House that was incorporated into the health-care law. The requirement "is meant to let people know what it is that they're consuming," she said.

Chain restaurant operators can somewhat legitimately complain that applying this rule to all and only restaurants with at least 20 branches is a bit unfair to them. Movie theater owners are grasping at straws here for an argument.

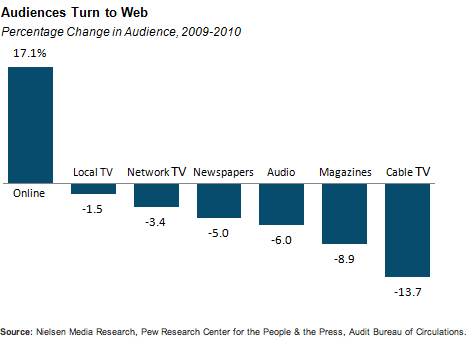

Cable News Sinking, NPR Rising

James O'Keefe's antics aside, I think National Public Radio will be okay in the long run because, as the latest Pew survey of journalism finds, listening to NPR is really popular:

Of all the traditional media, the audience for AM/FM radio has remained among the most stable. In all, 93% of Americans listened to AM/FM radio at some point during the week in 2010, according to data from Arbitron, and this has dropped only three percentage points in the last decade. News may have suffered more. According to the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, 16% of Americans say they get most of their national and international news from radio, down 6% from 2009. And 34% of Americans said they got some news on the radio "yesterday," down from 43% in 2000. NPR, by contrast, has flourished as commercial all-news radio programming has become scarcer. NPR's audience grew 3% in 2010, according to NPR internal data, to 27.2 million a week. That is up 58% since 2000.

Meanwhile, cable news is collapsing:

NPR, I might add, is doing really good stuff online with things like the Planet Money and Radiolab podcasts. I think it's noteworthy that despite the "decline" of old media, as best I can tell NPR, the BBC, and The New York Times all have much larger audiences than they did 10 years ago. A big part of what's happened is that the highest-quality media brands have extended their reach, even as lesser players have been hammered and new venues have come to the fore.

The Slippery Slope Of Unilateralism

I had an interesting back and forth several years ago with Anne-Marie Slaughter, then a professor at Princeton, later policy planning director at the State Department, and now back to academia about an old line from something she wrote where she said "the biggest problem with the Bush preemption strategy may be that it does not go far enough."

She clarified her position thusly:

I would not rule out unilateral action under any circumstances: a nation that had chosen to try unilaterally to stop the genocide in Rwanda in the face of both global and regional inaction would be hard to condemn. Similarly, it is imaginable that the United States or any other nation could conclude that it had absolutely no choice but to use force to defend its vital interests. But the entire point of our article was to minimize the likelihood of either of these situations ever occurring by embracing doctrines in the humanitarian and the non-proliferation area that would spur non-military collective action early in the game and would ensure global or at least regional authorization of force if it came to that. It is worth remembering that Kofi Annan himself told the General Assembly in September 2003, after the invasion of Iraq: "It is not enough to denounce unilateralism, unless we also face up squarely to the concerns that make some States feel uniquely vulnerable, since it is those concerns that drive them to take unilateral action. We must show that those concerns can, and will, be addressed effectively through collective action."

So fair enough. But now flash forward to March of 2011 and it seems to me that the Obama administration in which Slaughter so recently served is, in fact, trying to engage in some non-military collective action vis-à-vis Libya. But she has an op-ed in The New York slamming the president for "Fiddling While Libya Burns" arguing that not only should we push for UN Security Council military intervention in Libya, but that if that fails we should intervene anyway: "If the Security Council fails to act, then we should recognize the opposition Libyan National Council as the legitimate government, as France has done, and work with the Arab League to give the council any assistance it requests."

Gone missing here is any real sense of using American leadership to promote a rules-based global order. Instead it seems to me that we're headed down a slippery slope of unilateralism. The violence taking place in Libya today is no Rwandan genocide. Far from being a threat to global non-proliferation norms, the Libyan government brokered a deal with western leaders years ago to give them up precisely in order to enhance its standing as a legitimate government. So what is the actual standard being proposed here for when the American government should offer military assistance to rebel groups? Leaving aside the myriad practical questions about intervention in Libya and think about what is the rule being proposed for this rule-based order? To me, this sounds like a proposal whose medium-term consequences will be to return Africa to its unhappy Cold War situation where it becomes a venue for endless superpower proxy conflicts.

If the US Congress has the appetite for spending a few billion dollars (PDF) on promoting some humanitarian objectives somewhere, surely there are some other human needs in the world. I wouldn't put Slaughter in this camp, but there's definitely a set of people in the United States who seem to want to help suffering people in the developing world if and only if that can be accomplished by killing other people in the developing world. It seems to me that it's a huge mistake to give in to that mentality.

Bank of Japan Easing

Given that rich country monetary policy (except in Sweden, Australia, and Canada) has been too tight for years, and it's been especially too tight in Japan, I can't but approve of the Bank of Japan's decision to ease in response to the earthquake/tsunami/meltdown problems hitting the country.

That said, I think this is primarily worth thinking about precisely because of how different this set of problems is from the "normal" ones of a great recession. Japan, after all, just got hit with a series of very real negative shocks. Buildings have fallen down. Buildings that are still standing have been damaged by water. Cars, trucks, and other pieces of useful equipment have been ruined. Roads, docks, and other pieces of transportation infrastructure have been blocked by debris. Several nuclear power reactors aren't generating electrical power. Tens of thousands of human beings are dead or injured.

These are not problems that can be solved on the demand side. If Japan is producing less two weeks after the earthquake than it was producing two weeks before the earthquake, that will be because the quake and associated traumas have in fact degraded the country's ability to produce goods and services. This is exactly what didn't strike the United States and Europe during the financial panic of 2007 and 2008. The United States is producing a low less than it could be producing primarily because a large number of people, the unemployed people, aren't producing anything at all. And yet we have functioning office buildings they could sit in. We have factories running at below capacity they could work in. We have trucks and cranes and other machines they could operate. We haven't been hit by an earthquake, our power plants aren't exploding, our roads aren't blocked by displaced automobiles, we're just not putting everyone to work. That's the very definition of a country with inadequate aggregate demand, and we should be fighting the situation with every tool at our disposal. Instead the debate in congress is about how much short-term spending to cut, and voices slamming the Fed for being too loose continue to be heard louder than those slamming it for being too tight.

The Modern Prometheus

From the annals of unusual pronunciation:

I'm looking forward to their innovative research on cadavers.

March 13, 2011

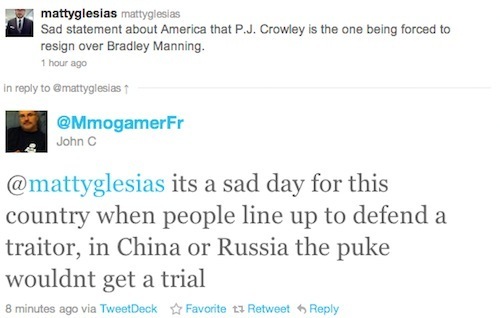

A Revealing Reply

Here an exchange I had earlier today:

This kind of thing makes me slightly hopeful about America. Bradley Manning, of course, hasn't had a trial. But it's obvious that many of the people who think they favor what's being done to him don't actually realize this. They take it for granted that in the United States of America punishment is for people who've been put on trial and convicted of crimes.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers