Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2393

March 11, 2011

In Defense of the Commerce Department

Since I've been making fun of Commerce Secretaries lately, it's worth being serious for a moment and noting that the US Department of Commerce actually does do important stuff. The National Institutes of Standards and Technology aren't at the center of a lot of hot-button fights, but we need standards. The Patent and Trademark Office is, obviously, a critical shaper of innovation. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration does useful scientific work. The importance of the Census is obvious. And the statistics generated by the Bureau of Economic Analysis are unquestionably useful.

The problem for the Secretary of Commerce is that this is a pretty random grab-bag of agencies. There's no "Obama Commerce Agenda" for Gary Locke's successor to spearhead. Nor do the heads of these different agencies constitute any kind of "Commerce team" for the Secretary to lead. This contrasts even with the relatively lowly HUD. Consequently, Secretary of Commerce is kind of a nothing job even though in the aggregate a lot of stuff is happening under his nominal purview.

In light of all that, and my considered study of the history of Secretaries of Commerce, my advice to the White House is that the job is best used to elevate the profile of a talented young politician to help set him or her up for higher office down the road. Someone like a mayor who might do the job for a a few years and then run for Senate or Governor.

How Public Opinion Does Matter

(cc photo by joost ijmuiden)

I feel like Duncan Black's written this post a million times:

Nobody cares about the deficit. Why don't people understand this?

This question has a real answer, though. Politicians don't understand that the voters don't care about the deficit because the voters themselves don't understand that they don't care about the deficit. Black, Paul Krugman, Brad DeLong, and I all believe that with unemployment high and interest rates and inflation low that a larger short-term deficit will help post real output and reduce unemployment. If most people agreed with that, then politicians would talk about the deficit in a different way.

But they don't. Public understanding of fiscal policy is hazy, inaccurate, and dominated by fallacious analogies between a national government and a household. What's more, voters believe that deficits are primarily driven by wasteful government spending. So when a recession strikes the deficit spikes, and people complain. The smart thing for a politician to do under the circumstances is ignore the voters, do what you can to fix the economy, and recognize that in the end the economy drives public opinion. But of course much like the voters themselves, many politicians and political staffers are not that savvy about New Keynesian macroeconomic models. Indeed, it seems to me that many grassroots proponents of expansionary fiscal policy seem to actually be in the grips of the broken windows fallacy. Over the long-term, the country and the world will be a lot better off if we can improve people's understanding of the business cycle. And improvement on the margin counts. It's not that everyone needs to be expert in this subject, but people all up and down the spectrum of "need-to-know"-ness (politicians, staffers, journalists, voters) could be better informed than they are.

Layoffs Mysteriously Averted By Non-Budgetary Bill

The procedural move that Scott Walker used to defeat the Democratic flee-abuster of his anti-union bill was to strip out enough provisions to make it non-budgetary. Which leaves this somewhat mysterious:

Gov. Scott Walker announced on Friday that he was rescinding layoff notices for 1,500 state workers after Wisconsin lawmakers approved his plan to cut collective bargaining rights and benefits for public employees. The approval, after nearly a month of angry demonstrations and procedural maneuvering, will create enough budget savings, Mr. Walker said, that layoffs will not be needed now.

How is that non-budgetary?

Oil: A Commodity Traded On A Global Marketplace

With gasoline prices increasingly in the news as a political story, I think it's important to lay down a marker. The price of gasoline is, obviously, intimately related to the price of oil. And oil price fluctuations are constantly a business story. And most media outlets are generally pretty responsible in their business reporting, not resorting to "he said, she said" BS unless it's actually unclear what's happening. Consequently, insofar as oil is written about in a newspaper's business pages, focus always remains on the fact that it's a global commodity. Oil is produced and consumed in particular places, but there's a single worldwide price of oil that's determined by global supply and global demand. It's not possible for one country to unilaterally alter the price its own citizens pay at the pump by altering the quantity of oil it produces. A new well in the United States has exactly the same impact on global prices as a new well in Norway or Venezuela or Saudi Arabis and thus the exactly the same impact on the price American consumers pay.

And yet turn it into a political story and suddenly all this knowledge drops away:

"What about domestic supply?" asked Sen. David Vitter (R-LA) this week. "What about the Gulf of Mexico? What about all of our other vast energy resources that we are taking off the table and shutting down?"

Rep. Doc Hastings (R-WA), who is chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee, has cataloged ways he says the administration has frustrated oil production, from suspended drilling leases to increased red tape. House Speaker John Boehner (R-OH) posted highlights of the list on his website.

"Since this administration has taken over, they have done everything to block energy development in this country," Hastings said.

Well what about domestic supply? Why would it matter if the supply is domestic?

Public Opinion And Elite Signalling

Kevin Drum alludes to the fact that when we had dinner together a couple of years ago in California, he took the view that progressive bloggers understate the importance of public opinion and I said I thought he was wrong and if anything we overstate it. I've since improved my view to a more nuanced one that I'm still having some trouble articulating in an ideal manner. But the sense in which I think public opinion is overrated is that people focus too much on polls about what "the people" think about "the issues." What a lot of analysis misses is that (a) many voters aren't paying attention at all and (b) most voters have stronger opinions about famous politicians than they do about issues.

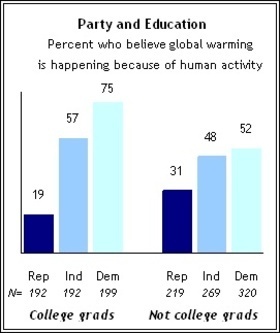

So consider that among self-identified Republicans, getting more education makes you less informed about global warming. But that's not because Republicans with BAs are ignorant compared to Republicans without them. On the contrary. Republicans with BAs are better informed about what the Republican view is and therefore worse informed about the underlying issue because the Republican position is mistaken.

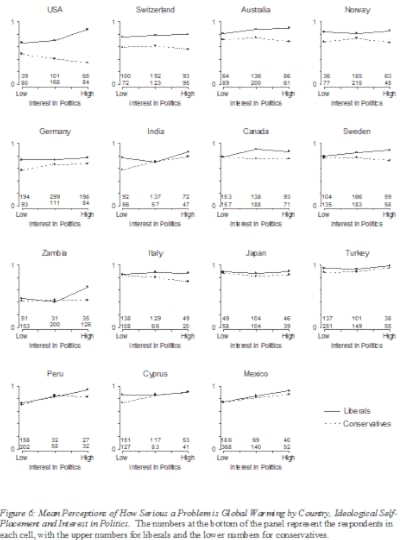

You can see the significance of elite signaling quite clearly in the international data:

In countries like the US and Australia where right-wing political elites are skeptical about global warming, you see the right-left split on climate science grow bigger as people pay more attention to politics. It looks very different in Germany. Well-informed voters are well informed about their ideological camp's position, not well-informed about the issues. And in the United States, a conservative voter who takes the climate issue seriously probably isn't a well-informed person who sees through Tom Coburn's cant, he's someone who's so ill-informed that he's not familiar with Coburn's cant.

This kind of thing is why I'm often skeptical of claims that "the White House needs to lead" on such and such. Americans have much firmer views of Barack Obama than they do of specific public policy issues. Obama can perhaps sell Obama's core supporters (working class minorities, not the hyper-ideological activist bloggers who often stand in for "the base" in media discussions) on things, but not the Obama-haters of the right. In the particular case of climate, the problem isn't that progressive need to do this or that to educate the voters about the science or the policy issues, is that conservative elites need to be convinced to care. John McCain, Mitt Romney, Mike Huckabee, and Sarah Palin all used to have a roughly accurate view of climate science. Were they to stick to that view, opinion would move. But they've all decided to be complicit in an unethical political strategy.

What I Learned At The Treasury Department

I was at the Treasury Department yesterday afternoon for one of these double super-secret background briefings with the Secretary and other senior officials. What I learned:

— 1. Treasury sees the benefits of focusing on the deficit as political rather than macroeconomic. Not in the "low politics" sense of trying to get a 1 percentage point boost in the polls, but in the "high politics" sense that you need to engage on the long-term deficit to avoid political momentum shifting sharply in the direction of contractionary short-term fiscal policy.

— 2. Treasury is distressed by the inability to get Federal Reserve Board and other economic policy officials confirmed. They think this is a serious problem, and they don't have confidence that there's a workable strategy and their disposal to resolve it.

— 3. Treasury claims that HAMP is currently working well, though it wasn't necessarily working well in the past.

So that's for your consideration. I dunno.

Tsunami

One of these news events that seems to demand note, but about which a humble political blogger can say little. Does the fact that an earthquake can serious damage a nuclear power plant without necessarily causing a radiation leak make us more or less sanguine about the idea of building additional nuclear facilities? I'm not sure whether this counts as "see, it's risky!' or "see, even in an earthquake it's not that bad."

March 10, 2011

Endgame

Mes chagrins, mes plaisirs:

— My public opinion flip-flop.

— Tim Pawlenty and the birthers.

— Anger management issues.

— Senior porn.

— Giant polar ice sheet loss.

Edith Piaf, "Je Ne Regret Rien".

Labor Unions and Tax Rates

Via John Sides, Jason Sorens presents research on the relationship between union density and tax rates:

What they show is that even when you control for overall state ideology (Democratic states have higher taxes, and really Democratic states have much higher taxes), union density increases tax rates. Increasing union density from 10% of the workforce, as in Nebraska, to 25%, as in Hawaii and New York, increases the tax burden by about one and a quarter percentage points of state personal income. For a sense of scale, the mean tax burden was 10.0% of personal income in 2008, and the standard deviation was 1.23, so this is essentially a standard deviation increase.

By passing right-to-work, Indiana could expect its unionization rate to drop anywhere between four and nine percentage points, taking in the range of values observed in other right-to-work states. This change would decrease Indiana's tax burden in the long run by between a third and three-quarters of a percentage point of personal income. The predicted effects in New Hampshire would be slightly less, since New Hampshire is slightly less unionized than Indiana.

It's difficult to make causal inferences based on these kind of statistical correlations, but the underlying theory here seems pretty clear. Under both the conservative "greedy public servants demand high pay for themselves" theory and the progressive "unions are a crucial counterweight to the political influence of the rich" theory, higher levels of public spending are a major political consequence of unionization. One alternative interpretation that I would like to see statistically tested would be that richer places have higher burdens (which is the general global and historical trend) and right to work laws happen to have proliferated in poor southern states 50 years ago.

On Not Surrendering to Bad Ideas

Ezra Klein's list of common mistakes made by economists when engaging with politics makes a lot of good points. But where I disagree with Ezra it's in what I see as an excessive level of concern with short-term practicality. Since one of his injunctions is to listen more to political scientists and another is to avoid the word "stochastic," I'll buttress the point with the observation that political science indicates that the operation of American politics is a good deal more stochastic than political practitioners (including journalists) generally realize. The conventional wisdom tends to simultaneously underrate the odds of the status quo persisting and underrate the odds of dramatic, rapid change.

Relatedly, I think there's often a tendency to systematically underrate the extent to which it's possible to change minds over time. That's one reason I was so interested in Anthony Appiah's book on moral revolutions. Public opinion about civil rights legislation changed a lot between 1915 and 1965 and a lot more between 1965 and 2005. Attitudes toward war have evolved considerably since Vietnam, and attitudes toward gays and lesbians have been completely revolutionized over the past 20 years.

None of that is to deny that there's a place in the world for concessions to political reality and for practical-minded people. But I think that as a society we're actually under-invested in discussions of impractical schemes and public efforts to remediate widespread intellectual errors. The course of the future is very uncertain. Three years ago, I would have agreed with the consensus that a cap-and-trade bill with side-deals was much more likely than a carbon tax. Today that now looks wrong to me and carbon tax as part of a long-term deficit reduction bill seems like the most likely (albeit not very likely) path to meaningful carbon pricing. In retrospect, we can see that George Allen's "macaca moment" led to a massive overhaul of American health care policy. Under the circumstances, the best thing for people knowledgeable about policy-relevant subject matter to do is to share what they know with as many people as possible and worry less about pre-trimming ideas to conform to guesstimates about what's possible/relevant/effective.

Most of all, people should think more about the long-term. Ask yourself what it was "feasible" to do to public opinion or public policy in 1811. And yet somehow things are better. And I'm optimistic we'll improve in the next 200 years.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers