Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2385

March 18, 2011

The Dubious Economics of Convention Centers

I live near the Washington Convention Center and it's struck me for years as a neighborhood-killing eyesore. And in general, whenever I see a downtown-adjacent convention center it always looks to me more like a force that's preventing revitalization of the area than leading it. The leading authority on this subject seems to be Heywood Sanders from UT-San Antonio who positively hates convention centers. Indeed, he seems to spend an unhealthy proportion of his time complaining about them. Josh Stephens did a good overview of the issue for The Next American City several years ago, but I thought there was one point where he should have pressed harder:

To repay the public largesse, convention centers almost always promise positive externalities and multipliers that could, in a fanciful world, justify hundreds of millions in public subsidies. But those externalities are vague, opaque and almost impossible to measure, especially ex ante. They are, therefore, almost impossible to oppose. Meanwhile, the hotels, real estate interests, downtown business groups and public officials who gain directly from convention business portray them as painless investments. "There's a limited range of things that cities can do and a limited range of things that mayors can say, 'Look what I did for the city,'" says Fainstein. "They like things that are visible … but I don't think that any rational benefit-cost analysis can justify it in most places."

The real issue here is that though the externalities are real enough, there's no reason to think property developers couldn't capture them. Running a convention center as a loss-leader for a hotel would be a perfectly reasonable thing for a private firm to do. Alternatively, you could run a hotel as a loss-leader for a convention center. And of course bundling a hotel with a restaurant or two or three is very normal. Or a consortium of local hotels might band together to finance the construction of a convention center. The point is that these externalities can be as large as you like and they still don't justify public subsidies for convention centers.

UNSC Passes Libya Resolution

I'm struggling to develop real convictions about this Libya business. On the one hand, you have everything done right—a UN Security Council resolution, backing from the Arab League and the OIC, and a bad guy who is, loosely speaking, adequately nuts to seemingly put everyone off. Meanwhile Gaddafi was acting yesterday like he was begging for this to happen, explicitly discussing the looming slaughter after he seizes Benghazi and making it hard for anyone to vote no on the resolution.

But it seems absurd to be saying we need a domestic discretionary spending freeze because somehow we're broke and yet there's plenty of funds available for a shiny new war in Libya. And it's a war whose objectives seem hazy. To halt Gaddafi's advances and de facto partition the country? To chase Gaddafi all the way out? If that happens, does "the Pottery Barn rule" apply and then we need to spend a decade supervising the country's domestic political conflicts? And why is this humanitarian emergency the one that needs urgent action? What about Saudi and Bahraini forces firing on demonstrators? What about the ongoing civil war in Ivory Coast where the health care system has completely collapsed? I feel like the countries that abstained at the UN—Brazil, India, China, Russia, Germany—mostly got this right, no eagerness to actually undertake a war but no willingness to condemn those who were. At the moment, it's not really even clear what the United States has committed to do. It's France and the UK who seem most eager to definitively commit military assets, and as far as I'm concerned the less of a leadership role the US takes in this the better since the endgame seems so murky.

March 17, 2011

Endgame

Nothing to do with you:

— McCain-Feingold empowers hyper-wealthy political entrepreneurs.

— The worst sports fans in America.

— Red light camera catches plenty of unsafe behavior.

— Of all the crazy ideas the Arizona right-wing is cooking up, this border militia thing is probably the worst.

— Puzzling infographic urges you to skip the fries and get drunk instead.

Lykke Li, "Rich Kid Blues".

Myron's Law and Romer's Corollary

This Paul Romer presentation (PDF) for the IMF makes an excellent point. He quotes Myron's Law: "Asymptotically, any finite tax code collects zero revenue."

That's to say that if you write down a tax law, then over time people will get better and better at tax evasion and revenue will slowly but surely drop. Then he offers Romer's Corollary: "Every decade or so, any finite system of financial regulation will lead to systemic financial crisis."

That's exactly why I think it was misguided to criticize Dodd-Frank for relying on regulatory discretion rather than being entirely rule-based. A rule-based system would guarantee you no crisis for a while, but ultimately it presents a fixed target for canny bankers to exploit and undermine. Discretionary systems may well fail, especially if our politics remains dysfunction, but they offer the only hope we have.

The Changing Face of Texas

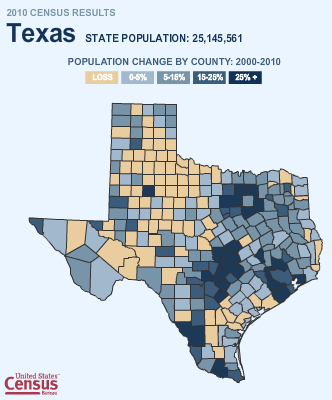

Texas' population grew rapidly over the past ten years from an already large base. That's why the state will be adding four congressional districts. So its fascinating to learn from the Census Bureau that even amidst 20 percent population growth, huge swathes of the state are actually losing people:

The result is a state becoming radically less rural as remote areas decline in population while central cities and (especially) suburbs boom at an incredible rate.

Triumph of the City

I reviewed Ed Glaeser's Triumph of the City: How Our Greatest Invention Makes Us Richer, Smarter, Greener, Healthier, and Happier for the Washington Monthly. It's a very good book and it does a lot to move our national understanding of these issues forward. You should buy it and read it and recommend it to your friends and tell publishers that there's skyrocketing demand for books on urban policy issues. But for the purposes of excerpting, let me focus on my disagreements with Glaeser:

But while Glaeser's overall thesis is compelling, his affection for tweaking liberals sometimes leads to questionable emphasis. Yes, historic preservation and environmental impact review can limit density. But they can also make cities more appealing and livable, and hence more attractive to employers and highly educated workers, which leads to economic growth that benefits everyone. Moreover, preservation and environmental review in America's central cities are hardly the main barriers to a denser country. Consider the D.C. area. To accommodate 600,000 additional people, the city of Washington, D.C., which is relatively small and already fairly compact, would need more than 4,300 more people per square mile, nearly a 50 percent increase in population density. By contrast, increasing the population density of adjoining Montgomery County, Maryland, up to the level of nearby Fairfax County, Virginia, would achieve the same thing. Suburban jurisdictions are big, and small differences in policy there can have a huge impact.

Glaeser's emphasis on preservation and environmental reviews also distracts attention from other measures that, in the vast majority of jurisdictions, are far more important in keeping densities low: minimum lot occupancy rules, bans on multifamily structures, mandated parking minimums, and so on all conspire to prevent efficient use of space.

In other words, I agree with Glaeser that historic preservation has gone too far in many instances, and I certainly agree that central cities should become friendlier to taller buildings. But if you want to talk about land use in a nationwide context, you need to talk about where the land is—mostly in the suburbs. The places where the inefficient use of land is at its most severe tend to be "inner ring" suburbs which ought to have grown denser over time as the metro areas they're part of grow.

Health and Taxes

To add one remark to of Erskine Bowles, it's worth underscoring that this particular claim is false:

He dismissed the idea that raising taxes alone might help erase the deficit, saying "raising taxes doesn't do a dern thing" to address health care costs that are projected to be a big driver of future fiscal problems.

As currently structured, the income tax code makes it cheaper for a firm to give its employees $1,000 worth of health insurance than to give them $1,000 in money. This boosts consumption of health care services among insured Americans to an artificially high level and contributes to high health care costs. What's more, because the subsidy is structured as an income tax deduction, the value of the subsidy is much greater to high-income individuals than it is to the middle class or the poor. Rescinding this subsidy is a distributively progressive tax measure that reduces the growth of health care costs. The Affordable Care Act takes some important steps in that direction, but the government could go further. That would reduce the deficit by raising revenue and slow health care cost inflation. This is a point that I believe is generally acknowledged by analysts of all stripes, though of course people who are more conservative would prefer to see the revenue used to reduce tax rates. The fact that Bowles doesn't seem to be remotely familiar with the relevant issues of health care economics perhaps explains why he thinks that health costs can best be contained by deploying a magic wand that simply "caps" growth in expenditures without doing anything to push on costs.

All Currencies Are Backed By a Promise

One reason that amateur state legislatures tend to produce government by lobbyist is that the only feasible alternative available is deeply amateurish government. For example, this from North Carolina:

Cautioning that the federal dollars in your wallet could soon be little more than green paper backed by broken promises, state Rep. Glen Bradley wants North Carolina to issue its own legal tender backed by silver and gold. The Republican from Youngsville has introduced a bill that would establish a legislative commission to study his plan for a state currency.

A similar measure already passed in Utah. But this reflects, among other things, a fundamental misunderstanding of the relationship between currency and promises. It's actually a gold-backed currency that's backed by nothing but promises. When America was on the gold standard, that meant that the government promised to give you such-and-such an amount of gold in exchange for a dollar. When FDR came into office, he decided the government needed expansionary monetary policy so he changed the price of gold. Under the Bretton Woods system, similarly, the government's promise to convert dollars to gold lasted a few decades and then it went away. It's a gold standard that represents a government promise that can (and will) be broken. Fiat currency is a government that's being honest with you. It's not pretending the money is anything other than what it is.

The practical response for Americans who question the forward-looking strength of the US dollar is just to buy another currency. Europe is run almost exclusively by center-right governing coalitions right now, so you can trust your money to them. Or maybe since all Europeans are socialists by definition you'd prefer to trust your money to the Canadian or British governments. You can buy Korean won or Australian dollars or Brazilian reals. You can even go out and buy actual bars of gold. I personally have a bunch of Chinese paper money in my sock drawer left over from my trip last year and held in that form in anticipation of future RMB appreciation. You can even buy gold. But whatever you do, don't entrust your money to promises by the North Carolina state government to give you gold in the future. That's just a sucker move that's going to leave you get stuck holding the bag next time there's a budget crisis.

Breaking: Republicans Obsessed With The Interests of Rich People

David Frum on Paul Ryan's Medicare privatization plan:

Ryan has for example proposed converting Medicare from an open-ended entitlement into a voucher for people currently in their 30s and 40s. At retirement, the voucher would cover some — but not all — Medicare costs. Retirees would be expected to use their own savings to cover any shortfall.

Good concept. But why should the voucher be the same for all, regardless of need? How is someone who has gone through life earning less than $44,000 — and half of all Americans do earn less than $44,000 — supposed to accumulate the savings to pay for insurance against the medical costs of the 2050s? And how is it fair to ask them to do so while paying taxes to support unlimited Medicare for everyone currently in their 60s and 70s, including retirees who earned many multiples of $44,000 during their working lives?

Ryan is right that we have to act early and decisively. But we cannot omit the third element: we have to act fairly and we have to act realistically. Bad enough that the young must pay twice. Worse if the poor young must pay twice to support the elderly rich.

Of course for Paul Ryan the regressive nature of the proposal is part of the appeal. Has Frum gone socialist or something? Did he miss the memo that the orthodox conservative view is that status quo American public policy is unfair to rich people? Its kind of an important part of the ideology.

How I Changed The Face of Washington Forever

From Shani Hilton's excellent "Confessions of a Black DC Gentrifier":

This shouldn't have been a surprise. The shift was happening even when I was in school, and it was quite noticeable then. A college friend noted at some point between freshman and senior year—after 2003, when Magic Johnson opened a Starbucks connected to the Howard University Bookstore on Georgia Avenue as part of a community development program called "Urban Coffee Opportunities"—that there were, as she put it, "just more white people around."

Note that this is exactly when I moved to the neighborhood—specifically 10th Street just north of U,. The key thing bringing me to that particular block at the time was less the Starbucks than the (no longer extant) Five Guys, which opened just before the chain went into its explosive growth phase. In retrospect, though, it seems to me that the real seminal event was not me moving to the neighborhood or the Five Guys opening, but the opening of the Columbia Heights and Petworth Metro stations in 1999 connecting the two stubs of the Green Line. That created a powerful north-south axis of gentrification extending from Chinatown all the way up to Looking Glass Lounge. None of this idle chatter should, however, distract from Shani's actual point which is to complicate the narrative in which "just as 'black people' is a proxy term for poor people in D.C., 'white people' is a proxy term for the young professionals who have moved in—and neither term is being accurately used."

One point I do want to emphasize, however, is that gentrification isn't really all about "displacing" former residents. The building I live in is on the site of what was the Northern Liberty Market until it was devastated by a fire in 1946. Then from 1965-1978 it was the home of the National Historic Wax Museum. It then stood vacant until the mid-1980s when it was torn down to become an open air parking lot. It retained that status for over twenty years until achieving its current status as a high-density mixed use residential development. We who live there (including, per Shani, many non-poor black people) are clearly gentrifiers, but we're also the only people to have ever lived in this location.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers