Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2381

March 22, 2011

The Nuke-Coal Tradeoff

In principle, you could substitute renewable energy for nuclear power. In practice:

HENRY DERWENT: [Japan's] plans to meet their Kyoto target will have to be changed because they're going to be emitting more.

EVE TROEH: Emitting more carbon as they make up for lost nuclear power with coal, gas and oil. Though, given the disaster, Japan could renegotiate its Kyoto goals. Europe is set to emit more as well. Germany has taken nuclear plants offline. Switzerland has suspended future projects. More fossil fuels there, too.

Nothing I've seen out of Japan really suggests to me that that this is a wise tradeoff. The main lesson I'm seeing is that getting hit by a 9.0 earthquake is an unimaginably horrible disaster. Fossil fuels are still dirty and dangerous.

March 21, 2011

Endgame

A different kind of way:

— Expect the White House to stay quiet on Social Security.

— New blog from the NY Fed.

— House loves farm subsidies wants to cut food stamps instead.

— One in five Air Force women say they've been sexually assaulted.

— Heavy smoking during pregnancy leads to crime down the road.

Thao & Mirah, "Eleven".

The Intervention Cycle

Leon Wieseltier, plumping for war per usual, asks: "Did our inaction in Rwanda reduce the frequency of malaria in Africa?"

That seems like a terrible way of looking at things. The United States of America traditionally didn't maintain a large standing military force. But in order to fight the Cold War, we created one. This national security establishment is a significant burden on the public purse and it does, in the aggregate, crowd out other possible public sector initiatives including international public health. It's true that once the military capability actually exists, the short-term cost of deploying it often looks low. This is Madeleine Albright's challenge to Colin Powell: What's the point of having this magnificent military if you're never going to use it. But if you do use it, then non-use as a rationale for reduced expenditures goes away. And that, again, crowds out other possible public sector initiatives including international public health.

Yet at the end of the day, promiscuous use of lethal violence seems like a very strange long-term strategy for promoting humanitarian outcomes. It's neither true that promiscuous use of lethal violence is a cost-effective means of humanitarianism nor is it true that America's capacity for lethal violence is primarily deployed for humanitarian purposes.

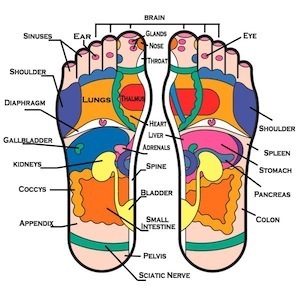

"Reflexologists" Seeking To Construct Foot Massage Cartel In New York

Another day, another spurious occupational licensing effort:

State Sen. Martin Golden and a handful of other lawmakers got what looked suspiciously like foot massages in the cavernous lobby of the Legislative Office Building. "They are looking for some of our brains," Golden (R-Brooklyn) quipped as a member of the New York State Reflexology Association rubbed down his bare feet. [...] The group was in Albany pushing for passage of an Assembly bill that would require licensing of reflexologists and set competence standards.

As ever, the question here is what's the market failure? The NYSRA can start a NYSRA Certified Reflexologist program if it wants, and then we'll see if the competence standards required to get certified meet the market test. The difference between these kind of licenses and regulation we need is that it really doesn't make sense to worry about a plague of bad foot massages being unleashed on the country. You can get rich polluting the air, so absent adequate regulation we'll have too much air pollution. But it's really hard to earn a living giving foot massages unless you have satisfied customers.

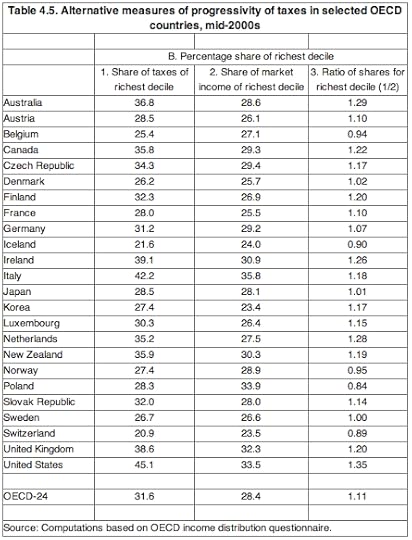

Unequal Incomes and the Unequal Tax Burden

GP writes:

Prof. Mankiw posted the following link on his blog — saying that it demonstrated that the U.S. had the most progressive tax system in the developed world:

This was a bit surprising to me, so I was wondering if you had any thoughts? I'm inclined to dismiss it by noting that the US probably has the most unequal distribution of wealth of all those countries and, hence, that our tax system is not sufficiently progressive. Am I missing something?

The answer is that the column labeled "Share of taxes of richest decile" is in fact the share of income taxes paid by the richest decile. The federal income tax in the United States does, in fact, have a progressive rate structure. Federal payroll taxes, state and local sales taxes, most excise taxes, and property taxes all have a regressive rate structure. So, yes, if you look exclusively at the most progressive element of the American tax code, it's highly progressive. If you compound that exercise by mislabeling your chart, then you can mislead people. You might think it's a little strange that Greg Mankiw, an economics professor, would mislead people by uncritically endorsing such a misleading chart but Mankiw believes that progressive taxation is immoral and should be opposed even if it enhances human welfare. Perhaps this same moral theory leads him to believe that misleading people about the subject is an act of justice. If so, then I'm not sure it's really in the interests of Harvard (or the many universities that assign his textbook) to entrust him with the instruction of teenage economics students.

Paying For Journalism

I think I'm the last blogger to comment on the NYT paywall:

"I believe that our journalism is very worth paying for," said Jill Abramson, The Times's managing editor for news. "In terms of ensuring our future success, it was important to put that to the test."

I also think the Times' journalism is worth paying for, and I'm happy to pay the price they're asking. But it's always worth emphasizing in these discussions that the widespread view among journalists that readers have traditionally paid for journalism is a mistake. Readers have traditionally paid for paper, ink, and distribution of physical media. The price goal of subscriptions is to cover costs so that you can maximize subscribers without going bankrupt. Then you make money by selling ads. The drive to produce journalism that people will want to pay for is, itself, part of the brave new world of the internet. I think it's fundamentally a good thing—the challenge is for people to do journalism that's so good that people will pay for it—but it's a new thing.

Public Ignorance Highlights The Importance of Accountability

I'm never that upset about reports of Americans' widespread civic ignorance. The nature of our party system means that a voter can really only express a very crude kind of thumbs up or thumbs down preference at the ballot box, so it's not clear to me how a more nuanced understanding of the world would actually effectuate itself in terms of policy change. But this is one of the reasons why I worry about the lack of accountability in our system. The way the system works, when it does work, is basically that the voters choose to send a bunch of representatives to Washington. Those representatives, in collaboration with their staff and sundry advocates and interest groups, try to figure out what should be done about various issues. And if things go well, then at the margin this helps incumbents. If things go poorly, then at the margin this hurts incumbents. Consequently, incumbent legislators are well-motivated to try to make sure that things go well.

That's not necessarily ideal (I won't invoke the "best system except for all the others line about representative democracy, which I think is too lazy about the possibilities of beneficial reform"), but it seems workable and sustainable. What doesn't seem sustainable to me is the system we've been evolving toward in which a legislative minority is able to block action and then reap the rewards of any policy failure that results. This feature of our institutional set-up, much more than public ignorance, threatens to wreck the "market" for sound public policy.

Libya and Signaling

I tweeted earlier that "Michael Lind's opposition to Libya War makes me more favorably disposed toward Obama's policy." That prompted some requests for clarification.

So for starters, obviously that's a joke. Michael Lind's opinions don't cut one way or another on the merits of Obama's policy. But I do find myself with mixed feelings on the matter. I also feel like this is just one of those weeks when it's really bad to be a general purpose political pundit who's supposed to write a high-volume blog. I can hardly just ignore Libya, but I don't have strong convictions one way or the other about it or a strong knowledge base. Had this not gotten UNSCR authorization, I'd be clearly opposed and I'd have lengthy and well-considered reasons for that opposition, but that's not the case.

As for Lind, it's just that generally speaking I find that Michael Lind is a forceful exponent of mistaken viewpoints. Back when we both wrote for TPM Cafe we would frequently clash over my view that Mexicans are human beings and that ethical public policy ought to consider the interests of Mexican people when considering immigration measures. That Lind's version of foreign policy realism is literally grounded in the straw man viewpoint that the welfare of foreigners should be completely irrelevant to our decision-making renders a lot of it suspect. So does the fact that his skepticism of foreign military entanglements doesn't extend to Vietnam. Less relevant to foreign policy, but still speaking to the overall question of judgment is his hatred of Star Wars.

The flipside of this, to be clear, is that some of the folks banging the drums loudest for war are the John McCains and Joe Liebermans of the world. And, again, it's often forgotten how cartoonish McCain's warmongering is. But recall that amidst the Kosovo War his view was that "the only thing to discuss with Milosevic is his unconditional surrender." That's insane. And it's amazing to me that one could take that line and emerge regarded by the media as being an unusually credible voice on foreign policy relative to other senators.

That returns us to the underlying merits of the issue about which, again, I have mixed feelings.

Libya and the Prospects for Success

Something to say on behalf of the Libya operation is that I think some of the nervous writing about this I've read has been overstating the difficulty of achieving our war aims. If you look at a map, you'll find that there's literally only one road between the crossroads town of Marsa al-Burayqah and the crossroads town of Ajdabiyah. If Gaddafi's regime doesn't collapse and we end up using western tactical air support to create a rebel safe haven in eastern Libya the operational task would basically amount to controlling just this one road. In the scheme of things that's a relatively simple simple task that it seems NATO could achieve at relatively low cost:

In terms of "what happens next?" type issues, this means that there's probably more to worry about if the rebels succeed in driving Gaddafi from power. That could lead to a very happy outcome, but it could also lead to the total disintegration of the Libyan state, new rounds of civil war, basically anything. According to a strict reading of the UNSC resolution, I think what's supposed to happen is that if the momentum shifts and Gaddafi's forces desert him, NATO congratulates itself on a job well done and washes its hands of the situation. Will that really happen?

Signaling and Higher Education

Duncan Black says he's "a big believer in the signaling model of higher education, in that a big chunk of its value is simply that it provides a signal to employers that you don't suck."

I never know what the baseline is here, but I think I'm less of a believer in the signaling model than are a lot of economist bloggers who I read. But what I do know is that both believers and skeptics in the signaling model ought to be highly motivated to try to find the country help find alternative signals. It's obvious that there's some signaling going on (I see resumés that say where people went to school but don't say what grades they got all the time) and getting a bachelor's degree is a very expensive form of signaling. What's more, the existence of and belief in the signaling effect serves to undermine the incentive for both students and faculty to actually focus on instruction. If everyone knew that there was some credible alternative signaling mechanism available, everybody would benefit. But it clearly doesn't work for eighteen year-olds to apply to jobs that would normally go to college graduates and just put their SAT score high up on the resume. There are a lot of coordination problems, social norms, etc.

But this country also has a lot of rich people interested in education policy, who oftentimes know a lot more about the business world than they actually do about education. Working on directly developing a mechanism that would make it easier for employees to signal "you should hire me" in a way that employers would regard as credible could produce huge gains.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers