Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2378

March 24, 2011

Racially Motivated Voting Is Not Just For White People

Dave Weigel observes that extraordinarily strong support for his re-election among non-white voters seems to have left Barack Obama in a strong position for 2012:

Meanwhile, the Field poll in California has Obama outperforming Bush and Clinton, at this point in their presidencies, on the re-elect. The comparison captures Bush at his last big surge of support, during the start of the Iraq War, so it's impressive. Look down at the Pew internals, though. Ninety-two percent of black voters want to re-elect Obama, as do 66 percent of Hispanics. Only one percent of blacks (!) and 16 percent of Hispanics want to vote against Obama. That's the source of the positive re-elect number — break it down to white voters, and only 36 percent of them want to re-elect him.

Ezra Klein had more on this yesterday, showing that this isn't just the usual black/white partisan gap. The Obama Era has led to an unprecedented level of racially motivated voting. And to state the obvious, it's not just racially motivated voting by white people. Black voters have been solid Democrats for a while now, but they're super-duper solid Obama supporters even though it's not like Obama's the most popular president in human history or anything.

March 23, 2011

Endgame

Four more years:

— I have it on good authority that Katie Roiphe lives in Brooklyn and the school she wouldn't name is St Ann's.

— For marijuana deregulation.

— Charles Murray will lecture on "The State of White America".

— "Capitalism Without Capitalists".

— The Groupon paradox.

Propagandhi, "May All Your Interventions Be Humanitarian".

CWA Happy With Cellular Merger

Good piece by Mike Elk lays out union enthusiasm for AT&T's takeover of T-Mobile. Basically, AT&T is unionized while the other cell phone operators aren't. So what's good for AT&T is good for the Communications Workers of America and the takeover presents an opportunity to organize the T-Mobile workforce.

I was in a bit of a Twitter dialogue with ex-intern Ryan McNeely about what's my point in bringing this kind of thing up. Mostly my point is that life is more complicated than people sometimes make it out to be. The optimal strategy for a private sector labor union is to represent the workforce of a monopolist and then team up with management to lobby for regulatory barriers to new competition. This is why the CWA aligns with AT&T on telecommunications policy, and it's also why manufacturing unions typically favor high trade barriers. A labor union can deliver much more value to its members if the unionized entity is a predatory monopolist. Given that reality, I can hardly begrudge unions from lobbying on behalf of their members' interests the same way that trade associations and business lobbies do. But I don't know any progressives who think that it's an "anti-labor" view to want a competitive telecommunications sector or that appropriate enforcement of anti-trust law is a union-busting plot. Efforts to expose domestic manufacturers to competition from foreign manufacturers or big city public school systems to competition from charter school operators tend to play quite differently with the progressive audience but it's the exact same structural situation in all cases.

Where The Poor People Are

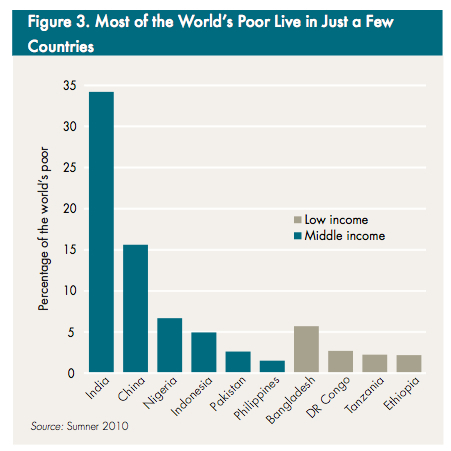

A new report from Andy Sumner at the Center for Global Development looks at the fact that thanks to economic growth in some poor countries, most poor people now live in middle-income states rather than poor ones. Specifically:

This is a reminder that if I ran American foreign policy, I'd be constantly asking "what can the United States do to help poor people in India?" That's an area where the potential humanitarian gains are gigantic and where there's strategic value in reenforcing cultural and political affinities with India. Somewhere at the nexus of interests and ideals is the fact that India vs China in economic performance is kind of a proving ground for liberal democracy.

The Mostly Hypothetical Case For Armed Humanitarianism

Rep Anthony Weiner (D-NY)

Speaking on the Don Imus show Tuesday, Rep Anthony Weiner endorsed military action in Libya with reference to Rwanda and the Holocaust:

My view is that there are times in American history — Rwanda was one, bombing the tracks during the onset to the Holocaust, that we could have sent a bomber wing in to take out the tracks, we didn't do it — we look back and we see we should use military force to try and defend people who can't defend themselves.

Maybe so. I think it's telling that enthusiasts for this kind of war typically have to make the case with reference to hypothetical success stories about military operations we didn't undertake. These are useful cases to deploy in arguments, because since the intervention didn't happen one doesn't need to wrestle with the potentially problematic consequences and downside risks. The key actual case is Kosovo, where American intervention was highly successful at helping the Kosovo Liberation Army achieve its political goal of independence from Serbia, but considerably less effective at actually preventing violence against civilians. What's more, though Kosovo independence is very nice for the Kosovar Albanians, it's hardly been a humanitarian boon to Kosovar Serbs and further afield it wound up creating problems for the good people of Georgia when Russia decided to use them as the target of retaliation for western recognition of Kosovo independence. We also have in Iraq and Afghanistan examples of military undertakings where the welfare of the inhabitants of the soon-to-be-bombed country was cited as a pro-bombing argument, and yet the actual results have been pretty mixed.

One thing you sometimes hear about Kosovo is the argument that the problem here isn't that intervention didn't work as well as its proponents promised, but that we didn't intervene forcefully enough. Perhaps if we'd sent ground forces in things would have gone better. And maybe so, but again I think it's a problem when all your best evidence is drawn from scenarios that didn't unfold. In Libya I guess we're at least finally getting a test case where the interventionists are getting their way and we can judge the results based on actual events.

Romer: Inaction on Unemployment is Shameful

People should listen to Christina Romer:

"I frankly don't understand why policy makers aren't more worried about the suffering of real families," former Council of Economic Advisors Chair Christina Romer, who left the Administration last fall, said during a discussion at Vanderbilt University in Nashville Tuesday. "I think there are tools we have tools we have that we can use, and I think it's shameful that we're not using them." [...]

"If I have a complaint about policy these days, it's that we're not doing enough," she said. "That goes all the way up to the Federal Reserve, [which] could be taking more aggressive action. It goes to the Congress and the Administration – there are fiscal policy actions they could be taking."

What can I say? She's right. She'd also be a great choice for a Federal Reserve Board of Governors seat. It's painful to watch the country grind through massive joblessness simply because key politicians don't seem to realize they have tools at their disposal.

Telecommunications Policy In The Early American Republic

Here's another slice of What Hath God Wrought:

The United States Post Office constituted the lifeblood of the communication system, and it was an agency of the federal government. The Constitution explicitly bestowed upon Congress the power "to establish post offices and post roads." Delivering the mail was by far the largest activity of the federal government. The postal service of the 1820s employed more people than the peacetime armed forces and more than all the rest of the civilian bureaucracy put together. Indeed, the U.S. Post Office was one of the largest and most geographically far-flung organizations in the world at the time. Between 1815 and 1830, the number of post offices grew from three thousand to eight thousand, most of them located in tiny villages and managed by part-time postmasters. This increase came about in response to thousands of petitions to Congress from small communities demanding post offices. Since mail was not delivered to homes and had to be picked up at the post office, it was a matter of concern that the office not be too distant. Authorities in the United States were far more accommodating in providing post offices to rural and remote areas than their counterparts in Western Europe, where the postal systems served only communities large enough to generate a profitable revenue. In 1831, the French visitor Alexis de Tocqueville called the American Post Office a "great link between minds" that penetrated into "the heart of the wilderness"; in 1832, the German political theorist Francis Lieber called it "one of the most effective elements of civilization."

A reminder that when big government is made to work well, the gains are gigantic. Nowadays it seems to me that publicly owned and operated post offices are basically anachronistic, but this was a crucial public service in geographically expanding and overwhelmingly rural country at a time when letters in the mail represented state of the art communications technology. And the underlying idea of the USPS, that the government should be facilitating the creation of high-quality communication, remains true today. That's why the question of the AT&T/TMobile merger seems so important. The fact that the Computer & Communications Industry Association (Google, Microsoft, EBay, Yahoo, Facebook) is vehemently opposed to the deal strikes me as a credible indication that letting it go through would be a mistake.

A Progressive Approach To Social Security

Robert Pozen has a piece in the Washington Post making the argument that progressives could embrace a vision of Social Security reform that reduces outlays while enhancing the program's progressive distributive impact. His proposal is similar in many ways to what CAP put ont he table late last year.

I think it's unfortunate, though, that Pozen didn't really engage with the political arguments around this subject. Progressive opponents of touching Social Security don't actually think we should just do nothing indefinitely and then have benefits fall off a cliff when the trust fund runs out in a couple of decades. Opponents of touching Social Security don't believe that restoring projected actuarial balance will in fact settle the issue, they think it will merely generate more headroom for income tax cuts. If that's true, then there's nothing to be gained by tinkering with Social Security in the current congress.

At any rate, if you look at what Pozen has to say on the merits the main upshot is that increasing the retirement age is a highly regressive move. And yet, that seems to be the move that has the most political support in the Beltway, presumably because politicians don't care about the interests of poor people. To me the real moral of the story isn't that progressives should be for or against reforming Social Security, it's that progressives should oppose raising the retirement age and insist that whatever cuts in spending on the elderly are enacted not take this form.

The Myth of Free Market Health Care

Senator Ron Johnson takes to the Wall Street Journal op-ed page to warn that the Affordable Care Act will lead to reduced levels of technological progress in medicine and reduced availability of health care services. His article is wrong in many points of detail, but it's at its most insane on the conceptual level. The fundamental issue here is that Johnson starts from the premise that the existing health care system he likes so much constitutes a free market in health care. It simply doesn't.

Almost fifty percent of health care dollars in the United States currently come from direct government expenditures on Medicare, Medicaid, and the like. And "private" health insurance is both heavily regulated in terms of coverage mandates, and heavily subsidized through the tax code. What's more, medical research is heavily subsidized by the federal government through direct expenditures and through the patent process. America's health care sector is innovative for the same reason our defense industries are innovative—they benefit from generous public subsidies. Removing all these subsidies might or might not be a good idea, but clearly one result of radically decreased spending on health care services would be a reduced pace of innovation in the sector. And yet I don't think Senator Johnson's main problem with the Affordable Care Act is that it spends too little money.

Conservative politicians often seem to me to be in this web of contradiction. On the one hand, they laud the consequences of generous public subsidies for the consumption of health care services and darkly warn of the perils of rationing. Then on the other hand, they insist that the projected rate of increase in government health care spending is far too high. Which is it?

Obtaining The Returns To Capital

Felix Salmon is worried about the ongoing trend for firms to avoid going public:

There are a few different reasons for this, but they basically boil down to the idea that it's a good idea for stock ownership to be as broad as possible. What we don't want is a world where most companies are owned by a small group of global plutocrats, living off the labor of the rest of us. Much better that as many Americans as possible share in the prosperity of the country as a whole by being able to invest in the stock market. I'm not saying that individual investors should go out and start picking individual stocks. But I am saying that equities provide bigger returns, over the long term, than other asset classes. And that therefore it's not good public policy for the ability to invest in an increasingly large part of the equity universe to be restricted to an ever-shrinking pool of well-connected global plutocrats.

I think this flirts with the view of the populist democratic possibilities of stock market investing that were ably critiqued in Tom Frank's classic "The God That Sucked". But Salmon doesn't ultimately embrace the view that Frank rightly deplored, which leaves him "not putting forward any policy prescriptions at all."

To me, though, it seems like the right thing to do is to just directly think about the issue of how best to ensure that everyone obtains the financial benefits of equity investments. And the answer, I think, is sovereign wealth funds. That's how they do it in Singapore and conceptually it's the right way to do it. An American version of Singapore's Central Provident Fund would be much too large for any market to absorb, but the US share of world GDP should shrink over time and it's conceivable that there would be some way to work this out on the state level to create smaller units. A fund like that would render the public listing issue irrelevant, since it would clearly have the scale to get in on the private equity game. This would, needless to say, entail injecting a hefty element of socialism into American public policy but I'm always hearing from smart conservatives how much they admire Singapore.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers