Matthew Yglesias's Blog, page 2376

March 25, 2011

Redistribution, 19th Century Style

Daniel Walker Howe explains that counterinsurgency has been difficult for a long time:

The Seminoles in Florida Territory proved the most difficult of the southeastern tribes to expel. Willing to fight for their homes, they put up a resolute resistance and benefited from a remote defensible bastion and the assistance of runaway slaves. A treaty consenting to Removal, extorted from a group of Seminoles in 1833 when they visited Oklahoma, was repudiated by the tribe but accepted as binding by the administration. In December 1835, a hundred soldiers under Major Francis Dade were annihilated by a combined force of Indians and blacks. When Jackson left office in March 1837, the federal government had undertaken a serious war effort, and the fate of the Seminole tribe was still unresolved. Before it was through, the government would spend ten times as much on subjugating the Seminoles alone as it had estimated Removal of all the tribes would cost.

I always think it's strange that people have this conception of the United States as a country built on laissez faire somehow. "Send in the army to kill the Indians and take their land" is kind of the ultimate big government program. The land was then sold (often at sub-market rates) and the revenue helped finance both the army and the transportation infrastructure needed to make the whole thing work.

The Problem With Waste Is The Waste

Like Atrios, I think there's something oddly pointless about the fetishization of long-term deficit projections:

We should spend less money on stupid wars. We should bring down the cost of our health care system, because we spend stupid amounts of money for a mediocre product, and a lot of that (most!) is government spending. But we shouldn't maintain the fantasy that any of these things will lower the deficit. If, for example, we reduce the rate of growth in health care costs, this means that future lawmakers will spend less money on health care than projected. It does not mean that the deficit will be lowered. It will only lower the deficit if lawmakers don't cut taxes on rich people or spend more money on future stupid wars.

Right. The problem with spending money in wasteful ways, is that it's wasteful to do so. The waste is bad and shifting resources to better uses would be a good idea. But the thing about the deficit that people tend to forget is that the last time the budget deficit went away, the conservative movement took the view that debt reduction was a bad thing. It's not that conservatives argued that cutting taxes was more important than reducing the deficit (though obviously they think that), they actually argued that one reason to cut taxes is that the existence of budget surpluses was a policy problem that had to be addressed. George W Bush gave the populist version of this argument, deeming the existence of a surplus a sign that the government was overcharging residents. And Alan Greenspan gave the highbrow view of this argument, theorizing that debt reduction would lead to government ownership of non-bond financial instruments and thus socialism.

Sadly, Beltway conventional wisdom fails to grasp the basic asymmetry that exists around this. There are many things progressives care about more than deficit reduction. But conservatives don't care about deficit reduction at all. They believe that absence of a deficit is a policy problem that needs to be remedied by large tax cuts.

Department of Fake Contradictions

The Myth Of The Bombing Induced Coup

As a headline "Allies Are Split on Goal and Exit Strategy in Libya" seems a bit overblown to me. Any time you have a bunch of people cooperating you'll have some disagreement. But I get worried when I read this reporting:

The United States has all but called for Colonel Qaddafi's overthrow from within — with American commanders on Thursday openly calling on the Libyan military to stop following orders — even as administration officials insist that is not the explicit objective of the bombing, and that their immediate goal is more narrowly defined.

There's nothing wrong with hoping for the best, but this particular form of hope—that if you bomb a country's military enough, the generals will rise up and overthrow the government—seems like a perennial myth of air power. It didn't work in Iraq either time, it didn't work against Serbia in 1999, and I'd be very surprised if it works in Libya. Air power can achieve a lot. A man on foot with a gun can't beat a tank, but if the man on foot is assisted by an airplane that can drop a bomb that blows the tank up, then he's in much better shape. Important elements of the American military and political culture, however, can seem to let go of the hope that you can achieve broader strategic objectives just by bombing. If that were true, then it would give the technologically advanced United States a relatively cheap means of achieving worldwide military hegemony. But it's not true. If bombing Libya results in regime change it will be because tactical air support makes it possible for rebels on the ground to win.

Romer on Boosting the Economy

(cc photo by LateNightTaskForce)

Ezra Klein draws former CEA Chair Christina Romer further out on her frustration at government passivity in the face of mass unemployment. My favorite part:

You've also criticized the Federal Reserve for not doing more. What would you like to see them doing?

I'm teaching a course this semester on macro policy from the Depression to today. One thing I had the class read was Ben Bernanke's 2002 paper on self-induced paralysis in Japan and all the things they should've been doing. My reaction to it was, 'I wish Ben would read this again.' It was a shame to do a round of quantitative easing and put a number on it. Why not just do it until it helped the economy? That's how you get the real expectations effect. So I would've made the quantitative easing bigger. If you look at the Fed futures market, people are expecting them to raise interest rates sooner than I think the Fed is likely to raise them. So I think something is going wrong with their communications policy. They could say we're not going to raise the rate until X date. Those would be two concrete things that wouldn't be difficult for them to do. More radically, they could go to a price-level target, which would allow inflation to be higher than the target for a few years in order to compensate for the past few years, when it's been lower than the target.

You can download "Japanese Monetary Policy: A Case of Self-Induced Paralysis" (PDF) for yourself if you like.

I further note that though a price-level target would be radical in some sense, in another sense it's anything but radical. It's what Michael Woodford thinks we should do and he's the leading monetary theorist out there. Don't take my word for it, look at Greg Mankiw's blurb on his book. Level targeting is the solution that all the literature recommends, and it's just not being done.

The Overemphasis of Tragedy

Via Charles Kenny, Karen Rothmyer writes about the overwhelming negativism of media coverage of Africa:

[T]he main reason for the continued dominance of such negative stereotypes, I have come to believe, may well be the influence of Western-based non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and international aid groups like United Nations agencies. These organizations understandably tend to focus not on what has been accomplished but on convincing people how much remains to be done. As a practical matter, they also need to attract funding. Together, these pressures create incentives to present as gloomy a picture of Africa as possible in order to keep attention and money flowing, and to enlist journalists in disseminating that picture.

The problem, as Kenny explains, is that even though this tactic of overemphasizing the negative works in any individual case, painting an overall picture of total despair is counterproductive. Futility is one of the key props of the rhetoric of reaction. If people don't realize that past efforts have helped achieve meaningful progress, they start tuning out particular situations and completely despairing of helping.

We've recently on the internet seen Libya hawks and Libya doves agree that killing people via aerial bombardment isn't a very cost-effective means of helping people. Under the circumstances, it's a bit mysterious why killing foreigners seems to be the most politically feasible way of getting the American political system to expend resources on trying to help foreigners. I think this too much tragedy issue may be part of the story—endless tales of woe lead people to have an exaggerated sense of futility about almost all efforts to help foreigners at the same time but nationalistic sentiment simultaneously creates an exaggerated sense of the efficacy of military force.

March 24, 2011

Endgame

You've come so very far:

— ICC chief prosector says Gaddafi will be indicted.

— Must read from Brian Beutler on the human consequences of ACA repeal.

— Tim Pawlenty's big challenging is that people keep forgetting he exists.

— Denmark should let the krone float, but I think this would violate some treaty commitments.

— Goat rodeo.

— The trouble with multilateralism.

For the coalition! It's British Sea Power, "Waving Flags"

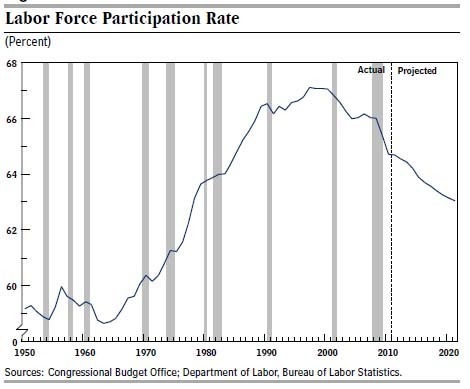

The Future of Labor Force Participation

It'll come as no surprise to anyone to learn that the recent bleak labor market has led to a decline in the labor force participation rate. But Catherine Rampell finds a new study out from the Congressional Budget Office (PDF) that predicts this is actually a long-term trend:

The report observes that the participation rate peaked at about 67 percent during the late 1990s and in 2000, since that's when baby boomers were in their prime working-age years of 25 to 54. Women had also been entering the labor force at a rapid clip. But since then the share of women who choose to work has fallen. In fact, it's now at the lowest level in nearly 20 years. Meanwhile baby boomers are reaching retirement age and dropping out of the labor force. Additionally, the share of people under age 25 who are working or looking for work has also fallen.

This logic seems a bit questionable to me. In the late 1990s we had a tight labor market. That was reflected in growing wages, and the growing wages reflected themselves in a growing labor force participation rate. In the aughts expansion, we didn't get to the part of the business cycle where wages go up. What's more, we never re-reached the previous peak of labor force participation. To me those sound like two ways of saying the same thing—weak labor market—not we had weak wage growth due to a weak labor market and this just happened to coincide with women and young people losing interest in work.

Libya and Nonproliferation

Jeffrey Lewis observes that one possible consequence of our military intervention against Gaddafi's government in Libya is to signal that it's foolish to sign deals with the West to abandon WMD programs.

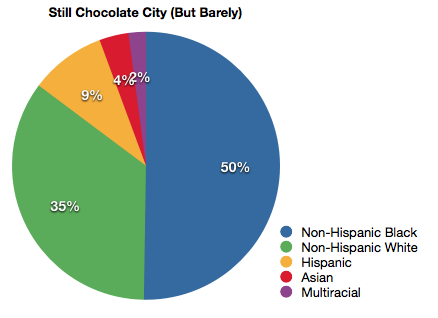

"Chocolate City" Status In The Balance

I'd been waiting with baited breath for new census data to prompt a bunch of stories about DC's decreasing blackness, and now that the new numbers are out they show exactly 50 percent of the city's residents to be non-Hispanic blacks:

The really interesting thing in the census data, though, is that I'd expected the very uneven pattern of growth in the city to force a major post-census redrawing of our Ward boundaries. It looks like I'm going to be disappointed. The two wards with the highest population growth—Ward 2 and Ward 6—had the lowest total populations after the 2000 census. Consequently, it'll only take a pretty minor redrawing of the lines (if any) to keep things in line.

Matthew Yglesias's Blog

- Matthew Yglesias's profile

- 72 followers